MacArthur 'Genius' Cleans Up Polluting Health Sector

Air Date: Week of October 9, 2015

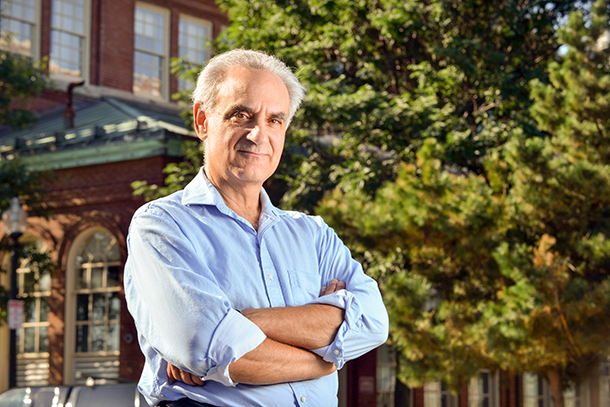

Gary Cohen (Photo: John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, CC-BY)

Twenty years ago, the health care industry produced more toxic dioxin emissions than any other sector, thanks to medical waste incinerators. Gary Cohen, Co-Founder and President of Health Care Without Harm, decided to clean it up, an effort that won him a 2015 MacArthur "genius grant" Fellowship. Cohen tells host Steve Curwood how greening health care practices can improve human welfare and the environment, and explains what still needs to be done.

Transcript

CURWOOD: The MacArthur Foundation recently named its 2015 Fellows, people chosen for “extraordinary originality and dedication in their creative pursuits.” As usual, the 24 Fellows selected for this so-called “genius grant” are an eclectic assortment. They include a classicist, a computational biologist, a puppetry artist, and Gary Cohen, an environmental health advocate, who is recognized for his efforts to improve the sustainability of healthcare through his nonprofit, Health Care Without Harm. Gary, welcome to Living on Earth!

COHEN: Thanks so much for having me, Steve!

CURWOOD: So how did you find out that you had been named a MacArthur ‘Genius’, and what was your reaction?

COHEN: The director of the program called me when I was in my office, and I was shocked and delighted by receiving such an honor.

CURWOOD: Out of the blue?

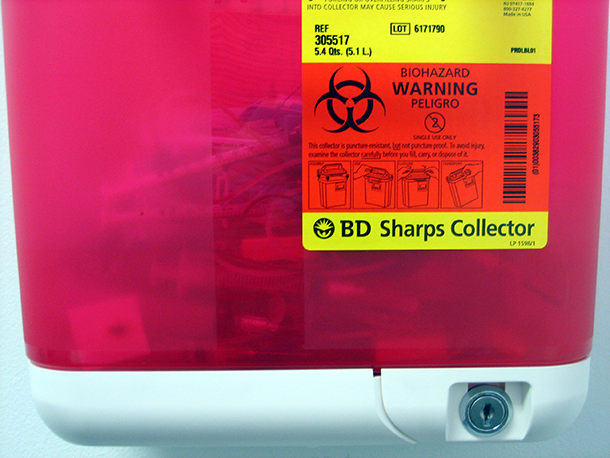

Medical waste incineration is a major source of dioxin, a known carcinogen. In the late 1990s Health Care Without Harm started a program to help hospitals reduce their waste; within a decade, the number of medical waste incinerators in the U.S. had dropped from 4,500 to 70. (Photo: Tyler, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

COHEN: Well, the irony is that I had met her serendipitously at a museum in Oxford, and I was sitting on a bench and this woman came and sat down next to me and we chatted for a long time, and then I asked her, “What you do?” And she said, “Oh I run the Fellows program at the MacArthur Foundation.” This was about five months ago — and I said, “Well that's interesting. Have you ever supported work in the environment health field?” And she says, “well, not really.” I said, “well there’s a lot of really interesting people doing work — important work — in this field, and you might consider it.” And that’s where we left it. And when I got the call from her last week, she said, you know, I know all about you when I came and sat down next to you. I was wanting to meet you and check you out, but I wasn’t going to tell you why.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] So you passed the interview.

COHEN: I guess so, I guess I did pass the interview.

CURWOOD: The Hippocratic oath tells doctors, “primum non nocere” — “first, do no harm.” In what ways does health care sometimes end up harming people and the environment?

COHEN: Well, the healthcare sector has all the contradictions of our economy that has been built on fossil fuels and toxic chemicals. So they're a major user of energy, which is derived from fossil fuels that have all sorts of public health impacts and are contributing to climate change; they’re one of the largest users of toxic chemicals, which are contributing to cancer and learning disabilities and all sorts of other health issues. And they serve food that's been drenched with pesticides, and meat that's been grown with the overuse of antibiotics. So there are so many different environmental issues the healthcare sector faces. And we took it upon ourselves to heal the healthcare industry’s pollution.

CURWOOD: What gave you the idea that this needed to be done?

COHEN: We learned in the mid 1990s that hospitals were the largest source of dioxin contamination in the country. And dioxin is linked to cancer and learning disabilities and damages for brain development, and the idea that hospitals were poisoning people in service of healing them was crazy, and a clarion call to address that. If we’re ever going to turn around the epidemic of chronic disease in our society, we have to get the healthcare sector to not contribute to it. We have to get the healthcare sector to show us the way out of this toxics problem, to show us the way out of our addiction to fossil fuels, to be the early adopters of renewable energy sources.

CURWOOD: So hospitals and dioxin — I imagine that came from their practice of incinerating so much of the plastics that they use. Tell me, how did you help the health sector confront its incinerator/dioxin problem?

COHEN: Well, for one we showed the hospitals that burning waste was incredibly inefficient, and it was creating this toxics problem that was then ubiquitous around the world, and that they could use alternative technologies, reduce their waste, save money in the process, and it was going to be good for the environment and good for the health of their communities. So we were able to go from over 4500 incinerators in the United States to less than 70 a decade later.

Mercury thermometers used to be a staple in hospitals across the U.S.; now, they’ve been phased out entirely. (Photo: Da Sal, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

Hospitals were also a significant source of mercury contamination because of all the broken mercury thermometers that wound up either being dumped down the drain or winding up in incinerators and then going out into environment, which would then build up in the environment, build up in the fish, and then build up in us because of the fish we ate. We started by convincing one hospital in Boston to eliminate its use of mercury thermometers, and then from there we were able to convince the other hospitals in Boston to follow suit. And then we brought that to many many other cities; in the end there were 5,000 hospitals that committed to go mercury free, there were 14 pharmacy chains, and then there were 28 European countries, and by 2013 there was a global treaty phasing out all mercury measuring devices by the year 2020.

CURWOOD: So you had a fair amount of success taking on the hospital incinerators. What are some the other programs that Health Care Without Harm is doing now?

COHEN: Well, the other programs that we’re working on is that we’re working a lot to change the purchasing practices of the hospital sector, so that they can support renewable energy, so they can buy products with green chemicals that don't contaminate their patients, or impact their workers. We are working with them to change their practices around the food they buy, so they could support sustainable farmers in the community, that bring healthy food, that create healing food environments in their facilities for their patients, but also their employees, who spend 12 hours a day there. So we’re trying to link the idea that food is medicine, and that healthcare, in its purchasing practices, can be involved in a much larger healing strategy. Not only healing individual patients, but healing communities they serve, and healing the planet. That's the new mission of healthcare in the 21st-century.

CURWOOD: Why, specifically, does the healthcare sector have a duty, a responsibility, to help tackle climate change?

Kaiser Permanente is one of Health Care Without Harm’s partners. (Photo: Fatima, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

COHEN: Well, we're learning now that the way that we will experience climate change around the world is through health impacts, whether that's increased asthma in inner cities, whether that means more illnesses related to heat stress, whether that means the increase of infectious diseases carried by mosquitoes to warmer climates, like Dengue fever and malaria, whether that's flooding or whether that's environmental refugees. Climate change is going to impact everyone's health around the planet. And when we can get the health care industry to rebrand climate change as a public health emergency, people will respond. If people think that climate change has everything to do with melting ice caps and polar bears, something very far away, they’re not going to be motivated to act. But if they understand that climate change impacts their health and the health of their children and their communities, they're motivated to act. And healthcare, it's 18% of the US economy and 10% globally, so we think it should lead the efforts of the rest of society to move away from fossil fuels toward a renewable energy economy.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about some of the ways that hospitals and clinics can be more ecologically sustainable.

COHEN: Well, hospitals and clinics can reduce the amount of waste they produce, they can reuse a lot of the materials that they do, they can design buildings that actually promote healing as opposed to making us sicker. They can reach out into the communities and set up farmers’ markets as places of access for people that can't get fresh fruits and vegetables. They can even intervene into the community and address the upstream social and environmental factors that are making people sick in the first place. So, for example, some hospitals are now realizing that it's the same kids that come again and again to the emergency room because of asthma. And so why is that? Well, when they've gone into people’s homes they realize that those families may have moldy carpets, they may be using pesticides, they may be using toxic cleaners. And when they intervene to provide solutions to those problems in people's homes, you can dramatically reduce re-hospitalization rates as well as lost work time and lost school time.

The Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital in Boston, which opened in 2013, was built to withstand the severe storms that the city is projected to experience as a result of climate change. (Photo: K-Sul3682, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: How aware of these problems is the medical profession as a whole, do you think?

COHEN: Well, doctors and nurses don't get trained around environmental health issues. In the course of a four-year medical training, they might get four hours on anything to do with the environment — and that might include issues around tobacco and alcohol. So we're not training the next generation of doctors and nurses to understand the essential connection between the environment and people's health.

CURWOOD: To what extent is that changing?

COHEN: I think the healthcare sector is waking up. Just this past spring, during public-health week, the president brought together deans of 30 different medical schools around the country who have all made commitments to teach the next generation of physicians about climate change and health. There's a number of universities now around the country who specialize in educating the next generations of clinicians around toxic chemicals and human health.

CURWOOD: Gary, how does it feel to be called a ‘genius’?

COHEN: I think the idea behind Health Care Without Harm was genius, and I'm just one of a team of many people that are helping to realize that vision. I’m very proud that over the last 20 years, Health Care Without Harm has built a social movement inside of the healthcare sector for environmental health and sustainability, so this work is now global in nature. There's projects happening in 50 countries around the world involving tens of thousands of people in hospitals, so we are moving from hospitals being cathedrals of chronic disease to being anchors for community wellness and sustainability.

CURWOOD: Gary Cohen is President and Co-Founder of Health Care Without Harm, a nonprofit based in Virginia, and the recipient of one of this year’s MacArthur ‘Genius’ Grants. Thanks so much for taking the time with us, Gary.

COHEN: Thanks so much Steve.

Links

MacArthur ‘genius’ Gary Cohen: Health industry’s epiphany creates science opportunity

Meet the 2015 MacArthur Fellows

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth