October 9, 2015

Air Date: October 9, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Pesticides, Herbicides and Childhood Cancers

View the page for this story

Pesticides and herbicides control pests and weeds, but new analysis suggests they also pose a significant threat to the health of young children. Host Steve Curwood and the study’s senior author, Chensheng Lu of the Harvard School of Public Health, report that exposures can increase children’s risk for leukemia, lymphoma and brain tumors. (01:55)

MacArthur 'Genius' Cleans Up Polluting Health Sector

View the page for this story

Twenty years ago, the health care industry produced more toxic dioxin emissions than any other sector, thanks to medical waste incinerators. Gary Cohen, Co-Founder and President of Health Care Without Harm, decided to clean it up, an effort that won him a 2015 MacArthur "genius grant" Fellowship. Cohen tells host Steve Curwood how greening health care practices can improve human welfare and the environment, and explains what still needs to be done. (10:05)

Pushing for Green Chemistry

View the page for this story

Today, we live in a stew of synthetic chemicals, and consumers know little or nothing about many of them as few are tested and proprietary information can conceal a product’s dangers. Ken Geiser, UMass Lowell Emeritus Professor, talks with host Steve Curwood about testing regimes and how we can make the chemical industry safer. (07:20)

Resetting the Gettysburg Battlefield Landscape

/ Lou BlouinView the page for this story

Each year, thousands of visitors travel to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania to walk the battlefield and imagine witnessing Pickett’s charge and the bloodiest clash of the Civil War. But the landscape has changed dramatically since 1863 and picturing the fight isn’t easy. Now, as The Allegheny Front’s Lou Blouin reports, the park service is using modern conservation tactics to take Gettysburg’s landscape back in time. (05:50)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Peter Dykstra discusses the recent disastrous rainstorms and new marine sanctuaries around the world with host Steve Curwood, and looks back on some misguided alarm about “killer bees” in the face of real threats from other invasive species. (04:40)

India at a Crossroads

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Investigative journalist Meera Subramanian crisscrossed India examining its environmental problems and searching for homegrown solutions described in her new book A River Runs Again. She tells Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer that everywhere she looked, she found serious concerns, but also hope for a better future. (17:15)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Gary Cohen, Ken Geiser, Meera Subramanian.

REPORTERS: Lou Blouin, Peter Dykstra, Helen Palmer

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The health sector accounts for almost a fifth of the U.S. economy, and it's one of the biggest polluters, but it doesn't have to be that way.

COHEN: Health care, in its purchasing practices, can be involved in a much larger healing strategy. Not only healing individual patients, but healing communities they serve, and healing the planet. That's the mission of healthcare in the twenty-first century.

CURWOOD: The MacArthur Genius helping to create "Healthcare Without Harm". Also, the Park Service has been giving an iconic monument a make-over.

LAWHON: We’re very careful about what we do. And we base it on historic evidence and studies. But at the same time, I mean, our job is to preserve and maintain these battlefield features. We can’t be so in awe of the Gettysburg battlefield that we keep our hands off of it.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week, on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

Pesticides, Herbicides and Childhood Cancers

Children are exposed to a wide range of chemicals around the home, everything from cleaning agents to pest control sprays. Many of these chemicals are ingested and residues are often found on clothes and skin. (Photo: CC0, public domain)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Pesticides and herbicides, by definition, are killers—killers of destructive insects and weeds—but that doesn’t mean they’re without risks to people, particularly children and infants. A new “study of studies” from the Harvard School of Public Health found that the dangers from chemical exposure in and around the home might increase the risk of developing childhood cancers. The researchers pooled data from 16 international studies, comparing levels of pesticide exposure in groups of children with and without cancer. Flea and tick pet collars, roach and ant sprays and pest control services were common indoor exposures, while outdoor exposures were mainly from herbicide use. The study’s senior author, Professor Alex Lu, suspected that the recent uptick in childhood illnesses, particularly cancer, might be due to pesticide exposures in the home, but before this study, the data wasn’t there to support this. Now, says Professor Lu, there is more cause for concern.

LU: We find that for household members that report use of pesticides in indoors, specifically insecticides, there is a more than 40% increased risk of childhood leukemia or childhood lymphoma. Outdoor herbicide use also increased the risk of childhood leukemia 26%, but the association’s not as strong as indoor insecticide use.

CURWOOD: The study also found a weak link to another childhood cancer.

LU: We also looked at childhood brain tumors, but its association to either indoor insecticide use or outdoor herbicide use was not as strong as leukemia or lymphoma.

CURWOOD: But Alex Lu notes that reducing the risk of exposure is manageable, for instance using natural pest controls or fixing a window screen or a crack in the foundation of the home, could be enough to put some distance between children and pesticides.

Related links:

- Study Press Release: Exposure to pesticides in childhood linked to cancer

- Study: Residential Exposure to Pesticide During Childhood and Childhood Cancers: A Meta-Analysis

- More about the findings of the meta-analysis

MacArthur 'Genius' Cleans Up Polluting Health Sector

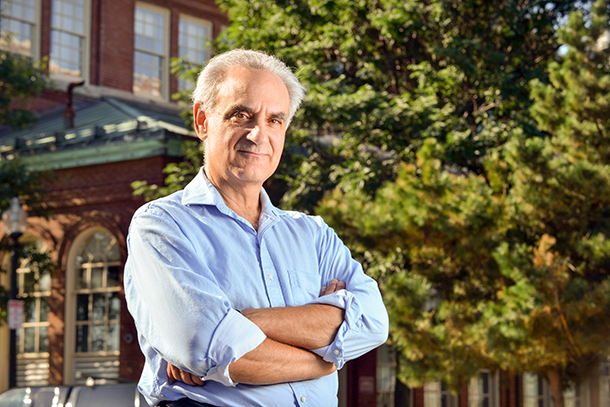

Gary Cohen (Photo: John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, CC-BY)

CURWOOD: The MacArthur Foundation recently named its 2015 Fellows, people chosen for “extraordinary originality and dedication in their creative pursuits.” As usual, the 24 Fellows selected for this so-called “genius grant” are an eclectic assortment. They include a classicist, a computational biologist, a puppetry artist, and Gary Cohen, an environmental health advocate, who is recognized for his efforts to improve the sustainability of healthcare through his nonprofit, Health Care Without Harm. Gary, welcome to Living on Earth!

COHEN: Thanks so much for having me, Steve!

CURWOOD: So how did you find out that you had been named a MacArthur ‘Genius’, and what was your reaction?

COHEN: The director of the program called me when I was in my office, and I was shocked and delighted by receiving such an honor.

CURWOOD: Out of the blue?

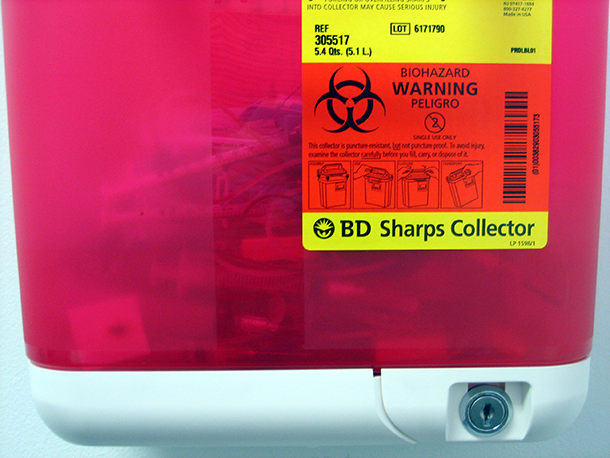

Medical waste incineration is a major source of dioxin, a known carcinogen. In the late 1990s Health Care Without Harm started a program to help hospitals reduce their waste; within a decade, the number of medical waste incinerators in the U.S. had dropped from 4,500 to 70. (Photo: Tyler, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

COHEN: Well, the irony is that I had met her serendipitously at a museum in Oxford, and I was sitting on a bench and this woman came and sat down next to me and we chatted for a long time, and then I asked her, “What you do?” And she said, “Oh I run the Fellows program at the MacArthur Foundation.” This was about five months ago — and I said, “Well that's interesting. Have you ever supported work in the environment health field?” And she says, “well, not really.” I said, “well there’s a lot of really interesting people doing work — important work — in this field, and you might consider it.” And that’s where we left it. And when I got the call from her last week, she said, you know, I know all about you when I came and sat down next to you. I was wanting to meet you and check you out, but I wasn’t going to tell you why.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] So you passed the interview.

COHEN: I guess so, I guess I did pass the interview.

CURWOOD: The Hippocratic oath tells doctors, “primum non nocere” — “first, do no harm.” In what ways does health care sometimes end up harming people and the environment?

COHEN: Well, the healthcare sector has all the contradictions of our economy that has been built on fossil fuels and toxic chemicals. So they're a major user of energy, which is derived from fossil fuels that have all sorts of public health impacts and are contributing to climate change; they’re one of the largest users of toxic chemicals, which are contributing to cancer and learning disabilities and all sorts of other health issues. And they serve food that's been drenched with pesticides, and meat that's been grown with the overuse of antibiotics. So there are so many different environmental issues the healthcare sector faces. And we took it upon ourselves to heal the healthcare industry’s pollution.

CURWOOD: What gave you the idea that this needed to be done?

COHEN: We learned in the mid 1990s that hospitals were the largest source of dioxin contamination in the country. And dioxin is linked to cancer and learning disabilities and damages for brain development, and the idea that hospitals were poisoning people in service of healing them was crazy, and a clarion call to address that. If we’re ever going to turn around the epidemic of chronic disease in our society, we have to get the healthcare sector to not contribute to it. We have to get the healthcare sector to show us the way out of this toxics problem, to show us the way out of our addiction to fossil fuels, to be the early adopters of renewable energy sources.

CURWOOD: So hospitals and dioxin — I imagine that came from their practice of incinerating so much of the plastics that they use. Tell me, how did you help the health sector confront its incinerator/dioxin problem?

COHEN: Well, for one we showed the hospitals that burning waste was incredibly inefficient, and it was creating this toxics problem that was then ubiquitous around the world, and that they could use alternative technologies, reduce their waste, save money in the process, and it was going to be good for the environment and good for the health of their communities. So we were able to go from over 4500 incinerators in the United States to less than 70 a decade later.

Mercury thermometers used to be a staple in hospitals across the U.S.; now, they’ve been phased out entirely. (Photo: Da Sal, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

Hospitals were also a significant source of mercury contamination because of all the broken mercury thermometers that wound up either being dumped down the drain or winding up in incinerators and then going out into environment, which would then build up in the environment, build up in the fish, and then build up in us because of the fish we ate. We started by convincing one hospital in Boston to eliminate its use of mercury thermometers, and then from there we were able to convince the other hospitals in Boston to follow suit. And then we brought that to many many other cities; in the end there were 5,000 hospitals that committed to go mercury free, there were 14 pharmacy chains, and then there were 28 European countries, and by 2013 there was a global treaty phasing out all mercury measuring devices by the year 2020.

CURWOOD: So you had a fair amount of success taking on the hospital incinerators. What are some the other programs that Health Care Without Harm is doing now?

COHEN: Well, the other programs that we’re working on is that we’re working a lot to change the purchasing practices of the hospital sector, so that they can support renewable energy, so they can buy products with green chemicals that don't contaminate their patients, or impact their workers. We are working with them to change their practices around the food they buy, so they could support sustainable farmers in the community, that bring healthy food, that create healing food environments in their facilities for their patients, but also their employees, who spend 12 hours a day there. So we’re trying to link the idea that food is medicine, and that healthcare, in its purchasing practices, can be involved in a much larger healing strategy. Not only healing individual patients, but healing communities they serve, and healing the planet. That's the new mission of healthcare in the 21st-century.

CURWOOD: Why, specifically, does the healthcare sector have a duty, a responsibility, to help tackle climate change?

Kaiser Permanente is one of Health Care Without Harm’s partners. (Photo: Fatima, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

COHEN: Well, we're learning now that the way that we will experience climate change around the world is through health impacts, whether that's increased asthma in inner cities, whether that means more illnesses related to heat stress, whether that means the increase of infectious diseases carried by mosquitoes to warmer climates, like Dengue fever and malaria, whether that's flooding or whether that's environmental refugees. Climate change is going to impact everyone's health around the planet. And when we can get the health care industry to rebrand climate change as a public health emergency, people will respond. If people think that climate change has everything to do with melting ice caps and polar bears, something very far away, they’re not going to be motivated to act. But if they understand that climate change impacts their health and the health of their children and their communities, they're motivated to act. And healthcare, it's 18% of the US economy and 10% globally, so we think it should lead the efforts of the rest of society to move away from fossil fuels toward a renewable energy economy.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about some of the ways that hospitals and clinics can be more ecologically sustainable.

COHEN: Well, hospitals and clinics can reduce the amount of waste they produce, they can reuse a lot of the materials that they do, they can design buildings that actually promote healing as opposed to making us sicker. They can reach out into the communities and set up farmers’ markets as places of access for people that can't get fresh fruits and vegetables. They can even intervene into the community and address the upstream social and environmental factors that are making people sick in the first place. So, for example, some hospitals are now realizing that it's the same kids that come again and again to the emergency room because of asthma. And so why is that? Well, when they've gone into people’s homes they realize that those families may have moldy carpets, they may be using pesticides, they may be using toxic cleaners. And when they intervene to provide solutions to those problems in people's homes, you can dramatically reduce re-hospitalization rates as well as lost work time and lost school time.

The Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital in Boston, which opened in 2013, was built to withstand the severe storms that the city is projected to experience as a result of climate change. (Photo: K-Sul3682, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: How aware of these problems is the medical profession as a whole, do you think?

COHEN: Well, doctors and nurses don't get trained around environmental health issues. In the course of a four-year medical training, they might get four hours on anything to do with the environment — and that might include issues around tobacco and alcohol. So we're not training the next generation of doctors and nurses to understand the essential connection between the environment and people's health.

CURWOOD: To what extent is that changing?

COHEN: I think the healthcare sector is waking up. Just this past spring, during public-health week, the president brought together deans of 30 different medical schools around the country who have all made commitments to teach the next generation of physicians about climate change and health. There's a number of universities now around the country who specialize in educating the next generations of clinicians around toxic chemicals and human health.

CURWOOD: Gary, how does it feel to be called a ‘genius’?

COHEN: I think the idea behind Health Care Without Harm was genius, and I'm just one of a team of many people that are helping to realize that vision. I’m very proud that over the last 20 years, Health Care Without Harm has built a social movement inside of the healthcare sector for environmental health and sustainability, so this work is now global in nature. There's projects happening in 50 countries around the world involving tens of thousands of people in hospitals, so we are moving from hospitals being cathedrals of chronic disease to being anchors for community wellness and sustainability.

CURWOOD: Gary Cohen is President and Co-Founder of Health Care Without Harm, a nonprofit based in Virginia, and the recipient of one of this year’s MacArthur ‘Genius’ Grants. Thanks so much for taking the time with us, Gary.

COHEN: Thanks so much Steve.

Related links:

- Health Care Without Harm

- MacArthur ‘genius’ Gary Cohen: Health industry’s epiphany creates science opportunity

- Meet the 2015 MacArthur Fellows

- Gary Cohen’s MacArthur Fellowship story

- About dioxins

- About Gary Cohen

[MUSIC: Darol Anger, “Lifeline,” from Tideline.]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, greening up the chemical landscape. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jake Shimabukuro et al, “Every Breath”]

Pushing for Green Chemistry

A petrochemical plant in Houston, Texas. The chemical industry is a huge consumer of fossil fuels. (Photo: Louis Vest, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. The statistics on chemical exposures in the US are startling – a decade ago the Environmental Working Group found an average of 200 different chemicals and pollutants in the cord blood of new-borns. These chemicals range from pesticides to flame retardants to waste from oil burning, and most of them are known carcinogens or toxic to the nervous system. Such findings gave added impetus to the Green Chemistry movement born in the 1990s, the idea that developing safer compounds would clean up the environment. But it has not advanced as far or as fast as it might have. Ken Geiser is emeritus professor of Work Environment at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell. He says that to properly protect our health we need to rethink our chemicals, how we develop, regulate and test them, and examine how they interact in our bodies and the environment.

GEISER: One of the problems is that we don't have the science on many chemicals so we only know about the hazards of those we studied. We have in the United States some 87,000 chemicals registered in the US, and what we really have knowledge about is maybe 5 to 8 or 9% of those, adequately. So there's a lot of chemicals we just simply don't know.

CURWOOD: So what would you say are the biggest flaws in the way that chemicals and the chemical industry in the United States is being regulated today?

GEISER: Well the chemical industry is not as regulated as an industry in terms of its own kind of occupational safety and health, the issue is the products of the industry. We have regulations on air emissions and water emissions and all, but we really don't have a lot of regulations on the chemicals in commerce—that is chemicals that go into products. We rely a lot on industry to do tests and a lot of that is proprietary, so either the agency doesn't see those tests or if they do that is all confidential. So it's very difficult to assess how many of those chemicals that are from the industry have been fully tested.

CURWOOD: I gather that other nations are actually doing better than we are in terms of cleaning up our chemical industries and reducing exposure for the public. Your views?

GEISER: Yea, this is a bit frustrating because the United States in the 1970s and through the early 1980s was really a model nation in setting new policies for chemicals, and after 1980 basically the Federal Government in the United States really had slowed down and there's been almost no additional new federal legislation of consequence since then. In the meantime, there have been changes outside the United States and the most dramatic has been in the European Union. In 2007 they overhauled the entire system to create something called REACH, which is an acronym for a new regulation which requires all firms that provide chemicals in Europe to register those chemicals and to provide full documentation on those chemicals and then allows the European Union to set limits such that the most hazardous chemicals would require authorization for continued use.

CURWOOD: So a lot of people have heard the term “Green Chemistry”, Professor Geiser, but what does that really mean and how would the chemical industry be different if it employed green chemistry? I gather one step is it wouldn't use nearly as much fossil fuel?

In recent years, particular toxic chemicals like BPA have gained notoriety among consumers, but the harmfulness of many other chemicals remains unknown. (Photo: Mark Morgan, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

GEISER: Green chemistry is a pretty exciting area of research, you’re right. About 20 years ago a handful of progressive chemists in the United States and Europe began a discussion based on the fact that we know a lot about chemicals and we know what generates hazards from chemicals and therefore it is possible that we could be designing chemicals that reduce the hazards in both the production of the chemicals but also in the actual product itself. This idea, the idea that chemists could be taking into account the environment and health effects of chemicals, as they do research, as they think about the synthesis of new chemicals, has sort of become a worldwide movement at this point. Here in United States this movement has taken off. There are green chemistry centers in many universities which are just asking chemists to use their knowledge about what generates the hazards of chemicals and see if there's ways to make chemicals that function effectively but simply don't have the hazardous profile. It's a very exciting movement, there have been efforts to try to get more funding for it through the federal government. There’s a bill now in Congress that would provide funding specifically for green chemistry. So it’s a very active area of research and work.

CURWOOD: What are some of the challenges then in switching over to greener chemical production processes?

GEISER: Well it depends. It depends on what level. At the level of commercial chemicals, that is chemicals used in hair dyes and cleaning products and things that are sort of what kind of are the end product of chemical production systems, there’s a lot of alternatives, there’s a lot of activity moving. You can go to the market and see all kinds of chemicals on the market today that says it doesn't contain this, it doesn't contain that. At the intermediate level further up the production system when you get to the specialty chemicals and the intermediaries and all, green chemistry has generated a lot of new thinking about you synthetic routes for making chemicals. But at the very upper level, at the very beginning, at what you call the “basic chemicals,” the “platform chemicals” there hasn't been much movement. We still are manufacturing our basic commodity chemicals in the same way that we were doing it 50, 60, 70 years ago. There’s not been much innovation. The industry has worked on process improvements but has not done a search for safer chemicals further up the production system.

Ken Geiser is the author of Chemicals Without Harm, Policies for a Sustainable World. (Photo: MIT Press)

CURWOOD: So how do we get a handle on this? How can ordinary people help shift this whole chemical conundrum?

GEISER: Well it's a good question. The first thing to say is people should shop smartly. Obviously read labels and buy organic. Use the internet, some of my favorite sites are Good Guidance, SkinDeep and EPA's new Safer Choice program to identify products that have safer ingredients in them. But it’s never — we’re never going to get there if all we do is shop better. We need to do much more and people can for instance meet with their local retailers and talk to them about what do they want to be on the shelves of their stores in their communities. They can fight for safer foods and products in their schools and their hospitals, in their social service institutions, in their communities, get those boards to basically specify safer products. They can press local and state officials to pass legislation to encourage substitutions themselves; California just passed a very far-reaching consumer products safety regulation that was driven by popular concern about chemicals in products. So there are many things citizens can do beyond just shopping wisely, but that’s the first step.

CURWOOD: Ken Geiser is an emeritus professor at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. His new book is called Chemicals without Harm: Policies for a Sustainable World. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today Professor.

GEISER: Steve, thank you very much, it was a pleasure.

Related links:

- Ken Geiser’s book, Chemicals Without Harm

- Good Guidance

- Skin Deep

- EPA’s Safer Choice

[MUSIC: Nile Rodgers, “Next”]

Resetting the Gettysburg Battlefield Landscape

Kyle Beger, 28, of St. Joseph, Missouri, visits "The Angle" at the Gettysburg battlefield, June 17, 2015. The site marks the place where Confederate soldiers briefly broke the Union line during Pickett's Charge on the third day of the battle. (Photo: Lou Blouin)

CURWOOD: One of the most visited sites of the Civil War is Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the scene of the bloodiest battle of that conflict. Visitors want to stand in the battlefield's most storied places, like Little Round Top or Devil's Den, and imagine the heroism and suffering that those landscapes witnessed. Until recently, though, it would have been hard to actually picture the scene at Gettysburg because of how dramatically the landscape has changed in the decades after the battle. But things have changed again, as the Allegheny Front's Lou Blouin reports.

BLOUIN: Even more than 150 years after the battle, there's still plenty at Gettysburg that kind of makes you feel like you're stepping back in time. You can even do a battlefield tour in a horse-drawn carriage.

[SOUND OF HORSES HOOVES]

BLOUIN: Katie Lawhon prefers to walk the battlefield. She’s been a park ranger here for more than 20 years. And you can still hear the excitement in her voice hikes some of the most legendary places on the battlefield.

LAWHON: So we’re at Devil’s Den, and this is important ground because we have heavy fighting on the second day of the battle. General Hood attacked nearly a mile of open ground, uphill, against this position, and they took it.

Park ranger Katie Lawhon stands near the Trostle Farm, Gettysburg National Military Park, June 17, 2015. The barn dates back to the time of the battle and is a favorite with tourists because of the cannonball hole left in the brick wall during the second day of the battle. (Photo: Lou Blouin)

BLOUIN: Devil's Den was one of the more dramatic landscapes at Gettysburg in July 1863. It was a sloped, open field, strewn with giant boulders. Soldiers would have used these rocks for temporary cover as they made their attacks. But by the 1990s, the whole area had grown up into a wall of trees. Lawhon says park rangers had to use historic photos to show tourists what it used to look like.

LAWHON: And a lot of people who studied the battlefield, they just walked down into those trees. They tried to walk in the footsteps of the soldiers. And they would do it, it was just a lot harder to understand.

BLOUIN: So in the late 1990s, the National Park Service started toying with a pretty radical idea: what if they rehabilitated the natural landscape at Gettysburg to look like it did in 1863? In places of heavy fighting like the Peach Orchard, they’d replant peach trees. And the meadows that had grown into forest since the battle? Well, those trees would get the axe. And the Park Service did it. Over the course of about 15 years.

LAWHON: We’re very careful about what we do. And we base it on historic evidence and studies. But at the same time, I mean, our job is to preserve and maintain these battlefield features. We can’t be so in awe of the Gettysburg battlefield that we keep our hands off of it.

BLOUIN: In all, the Park Service rehabbed more than 500 acres of the battlefield's most significant spots. They also removed manmade structures, including a motel, a 9-hole golf course, and even their own visitor center, which the Park Service plopped down in the 1960s at a key point on the Union line. Most of the heavy work is done now, but maintaining the battlefield's new look might prove to be an even bigger challenge. Head landscaper Randy Hill walks up a rocky hillside called Little Round Top. For historical accuracy, he actually has to maintain a clear-cut that was done here just before the battle.

HILL: For the area of Little Round Top, if you were a single person working with a single handsaw, it would probably take you a whole entire summer to keep this area maintained and clear. And then the next spring, you’d have volunteer woody vegetation popping right back up and you’d be right back at it again.

Little Round Top was the scene of intense fighting during the second day of the battle. For historical accuracy, the Park Service maintains a clear-cut that was done here just before the battle. (Photo: Library of Congress)

BLOUIN: Some natural details on the battlefield are more authentic than others. The historic cluster of trees that was the focal point for Pickett’s Charge actually doesn’t have any 1863 trees left in it. Randy Hill just trims the trees that are here now to the right shape and size. But one set of details the Park Service wants to make sure they get right, is minimizing the environmental impact of the battlefield rehab. Zack Bolitho manages natural resources at Gettysburg.

BOLITHO: We knew that we wanted to remove up to 500 acres of wooded habitat. And we said, well, we’ll never do it in any one portion of the park all at once. So the thought process is that things will have the opportunity to adapt as we change the landscape.

BLOUIN: Bolitho says in places like Devil’s Den, they decided to leave some non-historic trees when they found out they were home to a pair of nesting black vultures. And they mow fields as little as possible—and then, only after Gettysburg’s birds are finished nesting. The Park Service has even started using fire to mimic the way nature would regenerate all the open meadows that are again a part of the Gettysburg landscape.

BOLITHO: The Slyder field was our first 13-acre test burn. And it was a pretty good success—success being that it was the first time we did it. And people accepted the fact that Gettysburg could burn and not burn down a cultural resource.

Gettysburg Chief of Resource Management, Zach Bolitho, stands on the Slyder Farm near Devil's Den, Gettysburg National Military Park, June 17, 2015. (Photo: Lou Blouin)

BLOUIN: All in all in, the Park Service has done a pretty good job managing the environmental impacts, according to Randy Wilson, a professor of environmental science at Gettysburg College and an expert on public lands management. Wilson says it’s also important to remember that Gettysburg is a national military park, whose primary mission is protecting the historical values of the battlefield.

WILSON: So their efforts to try to intervene and say, look, there can also be a place where we can protect the environment, you know, I think that’s a very important step that they’ve taken.

BLOUIN: Wilson says evaluating whether the ongoing rehab at Gettysburg is a good thing for visitors, and all the species that call Gettysburg home, will take some time. He points out that visitation numbers at National Parks are down across the board, so it’s unclear whether the battlefield rehab will make Gettysburg more of a destination. But 28-year-old Kyle Beger, who’s here on a road trip from Missouri, says the fact that you can almost look back in time now at Gettysburg makes all the difference.

BEGER: The feeling you get here is just surreal. You know, we were just thinking earlier, it’s like, imagine all the cannon fire, what it was like to be here. It’s hard to explain, but it’s just incredible. I’m Lou Blouin in Gettysburg.

CURWOOD: Lou Blouin reports for the Pennsylvania public radio program, The Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Gettysburg Battlefield Gets an Extreme Makeover, reports The Allegheny Front

- Devil’s Den at Gettysburg

- The Peach Orchard

- Little Round Top

- Pickett’s Charge

[MUSIC: New Black Eagle Jazz Ban, “Old Rugged Cross,” live at Symphony Hall]

Beyond the Headlines

Flooding in South Carolina on Wednesday, October 7th. (Photo: Stephen Lehmann/ US Coast Guard, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From a visit to the past to a trip to the present. The guy with the present is Peter Dykstra, and he’s in a studio at radio station WABE in Atlanta, Georgia. Peter’s with the DailyClimate dot org and Environmental Health News that’s ehn dot org, and has been exploring beyond the headlines - hi there Peter!

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve. Last week, we wished a happy 45th birthday to NOAA, the government agency that among other things, keeps track of the weather for us. But not too far from here in South Carolina, the weather had them thinking of the other “Noah” – the one from the biblical book of Genesis and the forty days and forty nights of rain. Some portions of South Carolina got an astonishing two feet of rain in a few days. Columbia, the capital city, saw the wettest day in its recorded history, and residents were under a boil-water advisory.

CURWOOD: And think Peter, if that had been snow, two feet of rain would have translated into 24 feet or more of snow! And this was all from a convergence of Hurricane Joaquin and another storm system, right?

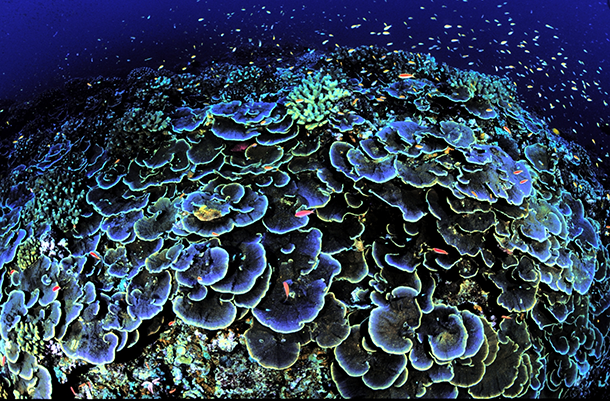

The coral Montipora aequituberculata attracts fish at Jarvis Island National Wildlife Refuge, part of Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument. (Photo: Jim E. Maragos/USFWS, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Right, and together they turned the firehose on South Carolina and kept it there. All while two other places very different from South Carolina had their own rainfall disasters. Heavy rains in Guatemala caused a mudslide that partially buried the town of Santa Catarina Pinula, leaving hundreds dead or missing. And the French Riviera was hit by a brutal storm, with flooding that killed at least nineteen. But back to South Carolina’s tragedy for a second. When New York and New Jersey got hit with Superstorm Sandy a few years back, 180 members of Congress said “NO!” to the federal aid proposed to help storm victims. That included five of the seven congressmen from South Carolina.

CURWOOD: Hmm, so let’s see if they’re in a more charitable mood for a Red State under blue water. What’s next for us?

DYKSTRA: More blue water, but it’s good news. There’s been an epidemic of newly-created marine reserves – big ones in remote ocean areas, and little ones in populated, historically significant areas. Chile just created the world’s third biggest marine sanctuary in the South Pacific. 200,000 square miles -- that’s almost the size of Texas--is now off limits to commercial fishing and oil & gas exploration near Easter Island, best known for its hulking stone carvings of humans with gigantic heads. New Zealand just announced creation of the Kermadec Islands Marine Sanctuary, which is slightly larger. And last year, President Obama announced the creation of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine Monument, biggest protected ocean area ever, west of Hawaii.

CURWOOD: So these huge areas are protected from potentially destructive commercial activity – but doesn’t the fact that they are so vast make them hard to patrol and protect?

Leafy Spurge is an invasive plant species that’s toxic to livestock, resulting in an estimated $35 - 45 million loss per year in US beef and hay production. (Photo: Anita Gould, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, it’s getting a little easier. Satellite monitoring, and some day perhaps even drones, can be deployed to follow pirate fishing vessels and reel them in. Oh, and two more small marine sanctuaries checked in last week here in the U.S. – one in Lake Michigan, another near the mouth of the Potomac River. Both are ecologically rich areas that also have historic value as the sites of many a shipwreck.

CURWOOD: And speaking of history, what's our history lesson this week?

DYKSTRA: Well it was the mid-Seventies, and Americans were hearing some potential horror stories about invasive species – kudzu was taking hold in the South, and in Florida, there were fears aboutwalking catfish – able to live for a spell out of water and drag themselves on their pectoral fins to the next pond – or your living room!! and eventually across America. But the biggest menace to America was Africanized honeybees – Killer Bees! And the most widely-consumed news source on killer bees was, in that uniquely American way, Saturday Night Live.

CURWOOD: And that became a recurring hit for the young show.

DYKSTRA: Making its debut forty years ago this week. But while there have been some outbreaks and attacks, the real killer bees never really swarmed, and haven’t overwhelmed conventional honeybees – sadly we’ve found lots of other ways to devastate honeybee populations – walking catfish haven’t walked very far, and kudzu – let’s just say it’s now a part of the landscape here in Georgia.

CURWOOD: And other unwelcome imports have left a mark.

DYKSTRA: In a huge way. Asian carp in the Mississippi, zebra mussels in the Great Lakes, Lionfish off the east coast. The western US has awful plants with delightful names like Leafy Spurge and Dalmatian Toad Flax, and in the East, insects like the Emerald Ash-Borer. Some hitching rides on ships and vehicles, some getting a boost from global warming. Watching the Killer Bees skits forty years later, the humor’s deeply insensitive, and maybe even racist, and Africanized honeybees aren’t the biggest invasive threat, but we are under ecological attack. In those South Carolina floods, there’s some creepy video of South American fire-ants locking their legs and jaws together to ride out the waters in a fire-ant raft.

CURWOOD: And you can find that video and more at our web-site, LOE dot org. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that ehn dot org and the DailyClimate – thanks Peter, talk to you next time.

DYKSTRA: All right, thanks a lot, talk to you soon.

Related links:

- Hope dims for finding survivors of deadly Guatemala mudslide

- French Riviera floods: Death toll rises to 19

- Where the No Votes on Sandy Aid Came From

- US declares 2 new marine sanctuaries, while Chile moves to protect waters near Easter Island

- Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument

- The “Killer Bees” Saturday Night Live skit

- National Invasive Species Information Center (NISIC)

[MUSIC: Tony Allen, “Asiko”]

CURWOOD: Coming up, an elemental trip to India. That's just ahead on Living on Earth, stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine, with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The David Grisman Quintet, “about walking”]

India at a Crossroads

All over India, cookstoves burning twigs and wood generate pollution inside homes. (Photo: Meera Subramanian)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. The world’s third largest greenhouse gas polluter, India, has laid out its emissions commitments for the upcoming climate conference in Paris. The country plans to vastly increase renewable energy use, but it also plans to expand nuclear and coal-fired power. India’s negotiators argue that, given how modest emissions are per capita, they need growth, as millions still live in deep poverty without clean water or power, and the environment often suffers as a result.

It was the environmental crisis – impoverished farmland, dying vultures, polluting cookstoves – that led investigative journalist Meera Subramanian to criss-cross the country in search of home-grown solutions already helping India deal with its multiple problems. Her new book is called “A River Runs Again” and she spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

PALMER: The organizing principle of your book, which is actually a book of journalism, you have a very interesting organizing principle of it, explain that to me.

In the Punjab village of Chaina, about a third of the 200 families farm organically and rely on insects like spiders to control harmful pests. (Photo: Meera Subramanian)

SUBRAMANIAN: Yeah, I decided to use the five elements to tell the story, I think it can be easy to be overwhelmed by approaching something as big as the state of the environment and the natural world in a place like India, and so I wanted to make it accessible to people. I wanted to bring stories about what people are doing on the ground in India today, right now.

PALMER: Well, you say the five elements – I think most of us only think of four elements.

SUBRAMANIAN: Right, it’s earth, water, fire, air and ether mad ether is the intangible essence of everything that's between everything else.

PALMER: And this is a particular Indian idea that it's five?

SUBRAMANIAN: Yeah, this is drawing on the Pancha mahabhuta which is the old Sanskrit idea of these five elements but it was interesting once I started investigating that I was finding that the idea of elements, it exists in Islam, it exists in ancient China, definitely in ancient Greece, I feel like what I found was that throughout time and throughout cultures people have tried to identify what makes this world that we inhabit.

PALMER: Well, first of all you give us earth, and you take on what is to most of us a kind of myth - the fantastic success of the Green Revolution, you take this on and you kind of do a bit of myth busting.

SUBRAMANIAN: I do. It's not that the Green Revolution didn't work on many levels, it did increase production but it seems like what the missing part of the equation is, is what the cost of that was and whether that works for the long-term. And so we're now 40-50 years into the Green Revolution and what we’re finding is that soil is depleted, water has run out, all of the inputs that go in do create food, but that food has chemicals in it that are changing our bodies, they're changing the environment that we live in, they’re changing the quality of the water that runs off of those fields and all of those things are having huge impacts.

The newly conserved water gives village children a place to play. (Photo: Meera Subramanian)

PALMER: We’ve actually also all heard stories in the newspapers about Indian farmers in terrible debt and killing themselves, and this is at least partly because of the cost of fertilizer.

SUBRAMANIAN: Right, it’s not just fertilizers, it’s the entire system and I think that was one part that made me think that we need to be more cautious about looking at the model of the Green Revolution because it is an entire economic system. I met one farmer in Punjab who just felt like it was a roller coaster, he felt like there was constant admission fees and every time you paid one ticket, it would work for a while and then the magic seed suddenly didn't work any more and a new pest had come and you had to get a new pesticide and he just felt like he was on this hamster wheel that he couldn't get off and he didn't like it, but he did step off, he stepped off and he said, “I'm going back to how used to do this, I’m going to go back to how my father farmed before all these chemicals were given”. And that's not without its challenges. So some of these farmers are really struggling and I think it was especially noteworthy that many of the farmers that I met were transitioning, so they were starting to do some of their acres in organic farming while they continued to do the rest of their's in traditional, conventional farming, using the chemicals and guess which ones they were choosing to feed themselves and their families?

PALMER: [LAUGHS]

SUBRAMANIAN: [LAUGHS] It was the organic and then the rest of it would go to market. A lot of the science does say that switching to organic is not going to get you the yields, but the seeds cost less, the inputs are less, soil becomes alive again, it holds water better, it decreases erosion, it's an amazing carbon storehouse which, as the climate changes, becomes a more important factor of agriculture which is a huge part of climate change right now, so all these factors come together.

PALMER: So, to move on from earth to water, as you do in your book, one point you're making about earth is that you're going back to how they used to do it, and that seems to be exactly what you're doing with water as well, or what you’re pointing to.

The organic seed bank of Navdanya, a nonprofit established by Vandana Shiva in 1984. (Photo: Meera Subramanian)

SUBRAMANIAN: Yeah, the situation with water was looking at an area in Rajasthan where the semi arid landscape, so water was pretty minimal, and they're pretty dependent on monsoon rains but the wells had just been depleted again -- this is population coming into it, as well as intensive agriculture, which both increase the demands and pressures on water systems and so the aquifer had gone down, the wells had all dried up and people were leaving because there was no way to work the land or have livestock there any more. And so what they did in this area in Rajasthan, led by the efforts of the man who is known as the Rainman of Rajasthan, Rajendra Singh, they started just building really small-scale dams, little check dams called johads, that helped capture the rains when they came and just that small action, of just helping the water pause when it comes, so that it doesn't just run off and cause erosion and disappear, you just help it stay put for just a short bit, and that helps it percolate down into the aquifer and basically constantly replenishing the system, and wells that had gone dry began to spring back to life. And what I found when I investigated, is a lot of the systems were in place in some way, all across ancient Asia and China and all these places, and it's just many of them had been forsaken and people started heading towards big dams and believing that you just wait, and the government will provide the water and people kind of stopped taking care of their own plots of land. And so there's something about people reinvesting in their local landscapes and taking part in the management of them in a really positive way.

PALMER: It reminds me actually of - if you go to Peru and places like that, where you see all these tiny little terraces, like two feet wide little terraces, all up the sides of the Andes there, you know, and they’re very ancient and that's how they grow their food.

SUBRAMANIAN: Right, it's a limited landscape so they figured out how to do it. There is something, I mean I think that's where the most hope comes for India, recapturing a lot of the ancient knowledge and also pairing it with all of the things that we now know. There's things that we know about, intensive agriculture and water management that are high-tech, looking at energy issues which is a huge part of what India’s facing right now in terms of the natural crises, is looking at smart grids and ways that we can be really efficient about using energy, and sometimes that has nothing to do with traditional knowledge, sometimes that's really going cutting-edge, but I think combining the best of the old and the best of the new you could really blaze a new path forward.

Artists celebrated the millions of vultures that cleaned up carcasses and the refuse of over a billion Indians. (Photo: Meera Subramanian)

PALMER: The next one you come to is fire, and you point to one of the biggest problems we know about, well, not only in India, in much of the developing world, the question of cook stoves and how women cook and how women are basically cooking on stoves that use biomass, that use dried dung, or use wood in some cases, and they're very very smoky, the women are getting sick and it produces terrible pollution, which is also bad for the planet. So I have to say, it's a simple problem but it doesn't seem to have a simple answer.

SUBRAMANIAN: I agree, it's a very, very complicated question. I used to work in the environmental nonprofit field when I was in my 20s, and part of that work was actually working on those cookstoves. We were helping develop and build them and they're really amazing and they’re really amazing, especially in the lab under very controlled circumstances but it was really tough for me as a reporter, because I really believed in the stoves and went out to find success stories and found a nonprofit that was doing very good work and was really held in high regards in Maharashtra, and I went to their quote unquote “smoke-free village”, their exemplary village, and I just had, I went into home after home and I just couldn't find a single one of the stoves working, just a couple years after they had been distributed. And so that just led to the question of - just asking ourselves, in terms of development, asking harder questions about, if something is not working, it doesn't mean that the stove is just not quite perfect yet and we just need to keep developing it, maybe there is something there that has a deeper question that needs to be asked, like one of the epidemiologists was questioning whether we should be asking the world's poor to be using a type of technology that we would never use.

Why don't we think about a way to get them something that is more akin to what we would be happy using, here in the developed world, and not try to just push those ideas of the perfect wood cookstove off to them, because the reality was that it just wasn't working on any large-scale. There are definitely successful fuel-efficient wood cookstove projects that are out there, and the stoves are being developed, and they are getting disseminated on a small scale, but the goals of the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves and other places that are really dedicated towards getting these stoves out there, just seem to have some kind of fundamental limitations, that to me, out there in the field, on the ground in India, seem to say that we need to maybe revision how we get energy to the world's poor.

Some of the staff members of BNHS (vulture) captive breeding program in Pinjore Haryana, India (Photo: Meera Subramanian)

PALMER: So air. You focus on something that is very much unloved and that is the vulture, but vultures are in trouble in India.

SUBRAMANIAN: They are in trouble and I love the vultures - I hope I'm not the only one [LAUGHS] - they are these amazing creatures, they just, without any appreciation they did this amazing job of basically cleaning up the residue of 1.2 billion people living on a subcontinent. They just go around and clean things up and then a really terrifying conservation story of a painkiller called Diclofenac, that humans have used for decades and then farmers in the ’90s started giving it to their livestock in India. And if that animal dies, and the vultures come and eat off of that carcass, the vultures have renal failure and they just die. It was just an amazing catastrophic collapse of salvation vultures in the span of just 10 years, looking at 99% decline, and so that just raised all these fascinating questions about how ecosystems work. Nature does not like a vacuum; feral dogs, which are extremely abundant in India, seem to have filled that vacuum; numbers correlate in terms of the vulture populations going down and the wild dog populations going up, and dogs cause a lot more problems than vultures, in terms of human interactions, vultures fly away from you, they really don't want to spend any time with humans but dogs are a very different troubling matter.

PALMER: Is this something that's actually been - I know you've done a lot of research on this - is this a problem that is actually getting close to being fixed?

SUBRAMANIAN: It's amazing with conservation, and many of these issues that sometimes it’s the smallest thing that can change a habit or behavior. And so India was great and pretty proactive, once they figured out that this was what was causing the decline, they banned Diclofenac for veterinary use, so it was still allowed for humans. But the crazy thing is that the human vial would be this big multidose vial, perfect for giving to a cow, so what the conservationists have been working on for years and successfully were able to implement, is removing that multidose vial, so now the vial for Diclofenac is human size. It means that if a farmer wants to give it to his cow, he has to go out and get a bunch and it's just a little inconvenient, and so the hope is just that little bit of an inconvenience will be enough to get it out of use, ’cause the black market was thriving in India and so even though the use had gone down after that ban, it had not gone away.

Over 4 million people die prematurely from household air pollution attributable to cooking indoors with solid fuels. More than 50% of premature deaths of children under 5 years old are caused by pneumonia from inhaling soot inside the home. (Photo: Meera Subramanian)

PALMER: Okay, finally we have ether. Now, you’ll have to explain to me why you chose the story you chose for ether.

SUBRAMANIAN: I felt like I wanted to talk and address the issue of population. Talking about the environment and talking about every human being born is an amazing miracle, but also is one more bit of pressure on natural resources, on the earth, so I wanted to look at that issue. So what I decided to do was go to Bihar, which is one of the states in the north that is most populous. Girls get married really young, they start having children very early, and they have some of the highest birthrates in the country of India. So that's where I went and I looked at sexual reproductive health training that was being done by an organization called Pathfinder International.

PALMER: You tell an amazing tale about it - I mean it's very graphic in terms of how it teaches boys and girls - teenagers - about this, it teaches them together. I was a little surprised, I mean it’s more graphic, for instance, than the sex education that mostly kids in America get.

SUBRAMANIAN: That's actually true! [LAUGHS] It's very straightforward but I think we underestimate how valuable information is for children everywhere. I think we are always growing up and trying to figure out how the world works and I think learning about the sexual and reproductive side of things is just as important for a teenage girl in Bihar as it is for someone here in the U.S. [LAUGHS] So, I think it's like just giving this very straightforward information ends up giving them power over other things as well. I was finding these young women to be incredibly empowered and it seemed like a big part of that was just learning the language of how to talk about themselves and voice their own desires. So, maybe I’ll just read you a short bit from the book that talks about that.

“People ask us, “Why do you go to these meetings, do they give you something?” Reena Kumari, an 18-year-old Bihari girl told me. I say, “When you go to pray, do you get something?” They say, “Well that one girl who did the training, she met a boy and she ran away.” She laughed and continued speaking quickly, in a strong voice. We argue back, “You had her for 15 years, and they had her for three days and you're saying we influenced her?” she said. “There's a flaw in your nurturing not in our friendship.”

“You fight back with your parents?” I said.

“Hum bolti hairi!.” she said. “We speak up! Before training, we didn't know anything but after, we do. We learned how to find the right words to negotiate. There are so many changes.”

To negotiate such changes is to ask for everything you want, knowing you might only get a fraction. It is to remain unflinching as you look forward into the future of India’s women and girls and the generations they will bear. The path ahead is difficult, littered with obstacles, still under construction. But I can imagine the youth I met in Bodh Gaya growing up in this new India, their India, moving forward down this road. They shape the way as they go. They link their fingers, they quicken their pace and their voices rising up into that space between spaces, are unafraid.’

A huge problem for India is its increasing population. A nonprofit Pathfinder International is educates teenagers on sexual and reproductive health. (Photo: Meera Subramanian)

PALMER: You end the book, your conclusion, is saying that you asked everybody, “Do you have hope?” I'd like to turn the tables on you and say, having crisscrossed India as you did, having done all this reporting, do you have hope?

SUBRAMANIAN: [LAUGHS] Ah see but you’re falling into the trap which is what I fell into, is I would ask that question as though “hope” were this noun, this binary thing where the only option is yes or no, do you have it or do not have it, and I'm to do the same thing that when I asked that question of people, I would do the acrobatics of like “well, yes but no,” “sometimes, on a good day..” but I felt like what I came out of the reporting thinking is that it's just this continual process that we have to work towards whatever future we want to envision for ourselves, and in the process of doing that, that is hope embodied. That is living it.

India has huge, huge challenges in front of it and Prime Minister Modi is really pushing development and won the landslide election last year on the platform of development and I feel like India just has a huge question before it of how is it going to develop. I think it could go is really amazing way if they tapped into some of the things that I experienced in India of people working on small-scale local issues across the board. If that was implemented and supported from the top down, if we looked at not pursuing nuclear power and more coal-fired power plants and more mega-dams that all have huge catastrophic problems if they go wrong and instead push alternatives like the technology is just moving forward by leaps and bounds, the costs are coming down. We can do this but it's going take the decision on all levels for India to move in that direction.

CURWOOD: Meera Subramanian’s new book is called “A River Runs Again” – and she spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Related link:

More about Meera Subramanian and “A River Runs Again”

[MUSIC: Shivkumar Sharma and Zakir Hussain, “Misra Pahadi,” Raga Misra Pahadi (Ameer Khusro Society of America, 1984)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation and brought to you from the campus of the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, and Jennifer Marquis. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jake Rego, Noel Flatt and Kevin Rinker; and thanks this week to radio station WABE in Atlanta Georgia. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at L-O-E Dot Org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living On Earth. And we tweet From @Livingonearth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Kendeda Fund, and Trinity University Press, publisher of “Moral Ground”, Ethical Action for a Planet in Peril 80 visionaries who agree with Pope Francis, climate change is a moral issue for each of us, T-U Press dot org, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth