Back to the Land in the Flower Power Era

Air Date: Week of May 13, 2016

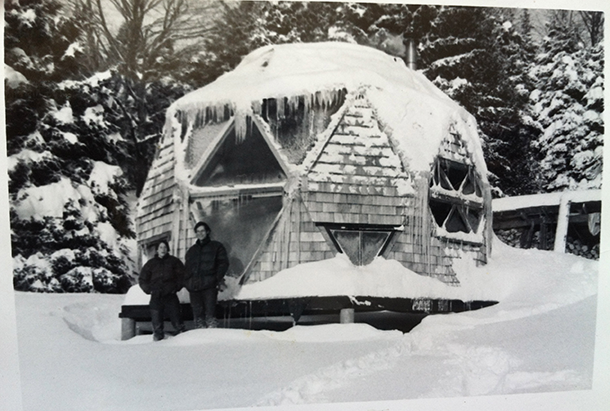

The author’s parents, Larry and Judy, in front of her childhood home, a geodesic dome inspired by the dome erected at the Myrtle Hill commune. (Photo: courtesy of Kate Daloz)

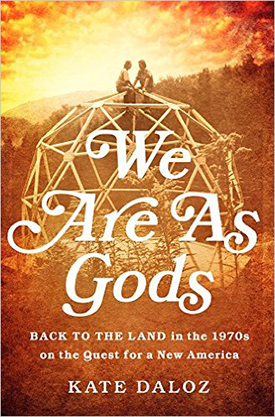

In the 1960s and 70s, many idealistic young Americans left cities and suburbs to build their own version of the American dream together on communal farms, often without a clue how to farm sustainably. Kate Daloz, author of “We Are As Gods: Back to the Land in the 1970s and the Quest for a New America”, brings us stories of this movement from the homesteaders who lived near the geodesic dome in Vermont that was her childhood home.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. As interest in sustainable, organic food has grown, so have the numbers of young entrepreneurs taking up farming to grow crops to sell directly to restaurants and at farmers markets. But that kind of movement is hardly new. Back in the 1960’s and 70’s thousands of idealistic young people left the city and went back to the land, looking to live sustainably and often communally. Now a new book captures that idealism: "We Are As Gods: Back to the Land in the 1970s and the Quest for a New America." It’s written by Kate Daloz, who teaches at Baruch College. It chronicles that era of communes and hitchhikers and recalls some homesteaders who lived over the hill from the geodesic dome that was her childhood home. Kate, welcome.

DALOZ: Thank you so much.

CURWOOD: What was motivating people back in the late ’60s, early ’70s to go back to the land to live and work on communal farms?

DALOZ: So, in addition to all of the political upheaval happening in the country as a whole, there was a really strong feeling at that time of wanting to rebel against the conformity of a ’50s childhood, and for a lot of people, they didn't want the same kind of two parents in the suburbs by themselves, so they really sought that out by going together - in a lot of cases to the country. They wanted to build their own houses, they wanted to grow their own food, and they wanted to learn skills that they didn't feel they had access to. They needed each other and so they went together because in the early days especially they needed a whole group of people to kind of make that experiment. To me, that's - was a really interesting reason why the communal movement and the back to land movement dovetailed in this period.

Loraine, the “heart and soul” of the Myrtle Hill commune, sits cross-legged in a field of sunflowers, 1970. (Photo: Fletcher Oakes)

CURWOOD: And they were drawn in by this book by Helen and Scott Nearing right? "Living the Good Life" they called it.

DALOZ: Yes, there had been this earlier communal movement that kind of was leading lots of people into communal houses in the rural areas and then the Nearings book was reissued and a whole new generation, a whole new round of single family homesteaders was inspired to kind of do the same thing.

CURWOOD: Good thing they didn't know how hard it is to farm, huh?

DALOZ: Yes, they really didn't. And that was another thing, the naïveté about what it would take to really live what they thought of at the time as a simple life, and you know, it involved less commercial goods but hauling water by hand, you know cutting your own firewood, none of that is simple. It's incredibly difficult. And the number of people, my parents included, who just talked about how many hours it took in a day to just make dinner or just heat your house. So they were surprised by that, but they want a lot from it too.

CURWOOD: The cover of your book has, I think it's a picture of your parents sitting on the scaffolds of the geodesic dome. What's the story behind that dome?

DALOZ: Yes, those are my parents and that is the house that I grew up in. My parents, Larry and Judy, had been in the Peace Corps. My dad had a very profound revelation at one point. He was in a village and realized he was the only person in the village at the time who didn't know how to build a house and didn't know how to get his own clothes, and he had a doctorate at that point. He suddenly was horrified to realize that for actually living day to day and surviving he was useless. My mother wanted the opportunity to do things that she had been told as a girl she wasn't capable of doing, so she wanted to build a house, she wanted to sort of have that freedom to test her own strength.

Neither of them had ever built anything before, so they knew they had to build something idiot proof and they heard about the dome at the commune Myrtle Hill, and they just were blown away by the beauty of it, and someone there lend them a book. It was Lloyd Kahn's “Domebook 2” and they just followed the instructions and minutes before that picture is taken they were convinced it wasn't going to work. It looks like Tinkertoys and then you put it together, it's very floppy, and then at the last second when you put that final bolt in, suddenly it becomes unbelievably strong and so that picture was taken by my aunt basically minutes after they've finished this dome structure and realized actually they were to be able to pull it off after all.

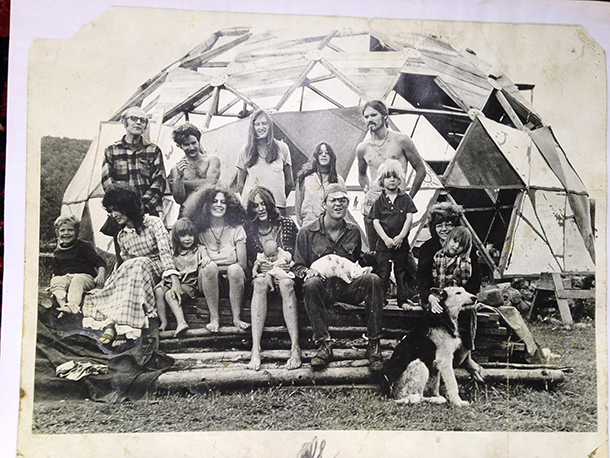

The Myrtle Hill communards and friends proudly gather in front of a geodesic dome in the summer of 1971. (Photo: courtesy of Kate Daloz)

CURWOOD: Now, talk to me about the farms and communes that you wrote about. Characterize them for us please.

DALOZ: One is called Myrtle Hill, and that was sort of your prototypical hippie commune and they would say that too. Twenty young people, they moved to an absolutely undeveloped former potato field and built from scratch their own house. They made decisions communally, they had all of their finances were pooled together. That was sort of the expectation, that everybody would share what they had. It was this intense intense experimentation socially and also just in the daily living.

The other commune I write about, Entropy Acres, they would actually only call themselves a semi-commune, which I think is fair. It was two couples, but they were both monogamous. They were living together kind of pooling resources and they were committed to farming without any combustion engines. So they used horses and they started a very early organic carrot farm, and their learning curve was immense, and then they also had unexpected twins, newborn twin babies, and so it was four adults and two newborn twins living in a house trying to farm without using any combustion engines at all.

CURWOOD: No fossil fuels...they sound a bit Amish to me.

DALOZ: I think they kind of wished they were. You know, it's interesting. The back to the land movement in a way had that same idea of the Amish kind of...they were really interested in the sort of 19th century technology, and the Amish Communities that still existed and exist today, in the 70s actually were a huge resource for suburban middle-class hippies that were trying to learn how to do the same thing.

CURWOOD: You know, people living in farm communities have generally been there for generation after generation after generation, and they learn when you're supposed to plant, how you can fix this kind of fence. How did these folks cope without that kind of history?

DALOZ: That's a great question. Well, one of the ways they did it was they went straight to those locals who had done it for generations at least in Vermont, but I'm hearing this in New Mexico and Oregon and other places as well. Really, for a lot of back to the landers, one of their huge resources were exactly does families who have been there for generations and did still remember those skills, and so they asked their neighbors and their neighbors had been watching them usually and thinking, “what is going on over there?” And in the case of Entropy Acres, the horse-farming commune that I write about, they were very lucky to have a local farmer named Luden Young, and he was really committed to making sure that they were safe. He saw that they didn't really know what they were doing and he came over and made sure that they had cleaned their chimney properly so that they wouldn't have a chimney fire with babies in the house. And so in turn, the people at Entropy Acres looked for a way to help Luden whenever they could, and when his barn burned down, they organized a barn raising to which they invited all the local hippies, including my parents, including people from the commune to help him build his barn again. So in a lot of places there was a kind of reciprocity of knowledge, so that's one huge huge huge source for a lot of back to the landers.

The creators of Entropy Acres, the second farming community explored in We Are As Gods, relied on 19th century technologies for their livelihood. (Photo: Fletcher Oakes)

CURWOOD: Please talk to me about some of the major issues that pop up when the groups of people in your book start living communal lifestyles. What are their successes, their failures?

DALOZ: I think the successes and failures, in some ways it seems completely obvious in retrospect, especially anyone who has ever had even just one roommate or two roommates can predict, you know, “who's going to do the dishes? what's the standard of cleanliness that we're going to keep?” and we’re talking about very often places that were committed to no electricity, and no running water, people who started out thinking, “oh, the way we'll form a non-suburban kind of community is we'll all live in one big house together and it'll be great!” and then they found out you know what, actually privacy that's not such a bad idea after all. Or just parenting with two people...that's hard enough without having it be 20 people who are not related to children. I heard from a lot of communards that they hit a turning point in their commitment to a commune when they saw other members of the community reprimand their child in a way that was not how they would do it.

CURWOOD: That is, if they knew who the parent was or who the dad was in some of these communes.

DALOZ: Yeah, I mean in most places I think there wasn't much question about parenthood. On one of the communes I write about, it is true, one of the main characters in the book Lorraine she deliberately made it impossible to know who is the father of her baby. This is a way of symbolically smashing the nuclear family structure.

CURWOOD: Tell me, how did that work out for her?

DALOZ: The part where she wasn't wrong was that the other women in the commune, the other mothers in the commune really were committed to taking care of each other's children. A thing nobody really foresaw was that in the first winter and then actually to be frank in a second winter also, all of the men left. In each of those winters, there's only one man who stayed and all of the rest of the people who were overwintered in the commune were women and children. And I think that they hadn't really foreseen how trying to find a place where there would be total freedom would mean that some people would exercise their total freedom by leaving.

CURWOOD: What happened to Lorraine? How did she succeed in building a new life without electricity and working 9 to 5 or being know like Mrs. Cleaver on "Leave It to Beaver"?

DALOZ: She really was the heart and soul of Myrtle Hill. She was there from the beginning and she was there until the end, and because she came from Vermont, she had a lot of skills that other suburbanites lacked. She was the only one who knew how to build a fire in a woodstove and things like that. She, like the other women in the commune - you know, this is the early seventies, it's right before the feminist movement - they accidentally kind of fell into very rigid gender roles. They did not mean to. They were thinking of themselves as very radical but at Myrtle Hill like a lot of other places, the women ended up doing a lot of the cooking and cleaning. Once they built the house and and it had an indoor kitchen, she became a very committed cook even after she left the commune - or after the commune kind of moved on. She was a cook and a baker for the rest of her life.

CURWOOD: So, Amy, she's another really strong woman in your book. How does her strength come out in the stories that you tell about her?

DALOZ: Amy was one of the people who I just loved interviewing the most. She had a terrible home life. She was the victim of terrible abuse at the hands of her stepfather and basically escaped, really just escaped and found her way to Vermont where she ended up in a commune called Johnson’s Pastures that had a lot of teenagers and they actually suffered a horrible fire in middle of the night that ended up killing four of the communards and Amy jumped out the window and escaped with her life and after that she happened to meet the people at Myrtle Hill and ended up with them and she will say to this day that they saved her life and they gave her a safe place to go from being a teenager to being a young adult. You don't usually think of a hippie commune as being a place that you find stability but she really did.

We Are As Gods: Back to the Land in the 1970s on the Quest for a New America is Kate Daloz’s first book. (Photo: Public Affairs Books)

CURWOOD: Hey, how do you think people in the back to the land movement compare to today's modern homesteaders here? Differences between now and then?

DALOZ: If I have to make a blanket statement, people who are throwing themselves into farming and homesteading experiments today, they don't seem to be quite as naïve about, like, the realities of a cash economy, for example, I mean it was very surprising to me the number of back to the landers who really thought they could just walk away from a cash economy and were kind of shocked to realize that it's not that fun to be cold and impoverished and living under these austere conditions and I don't get the impression that people aren't thinking about how they’re going to make a living once I get back to the land in the way that that the 70s generation - they just left and just went back there and figured it out when they got there.

CURWOOD: Of course times are much harder now than in the 60s and 70s. It didn't take much to get by financially then. Today, it's much harder.

DALOZ: Yes I think that's true, and I think also this baby boom generation, post-war generation, they really had a lot of confidence in the power of a college education. If you were college-educated or you were on that track to be college-educated, they were pretty confident that you could find a good job, so they weren't worried about walking away from that track and then going back to it later. And in fact, they turned out to be right and I'm not sure that my generation I don’t think had that same confidence and people younger than me even less so I think.

CURWOOD: So, how you see these folks that you wrote about in a sweep of American history, reaching back to Thoreau, for example, and coming forward now to today.

DALOZ: They have such an interesting place in history because while they thought of themselves as rebelling against a certain definition of America, what they did was so deeply American that they thought of themselves as pioneers in a lot of case, that romantic western history was absolutely part of a self conception especially in the early days but really throughout this idea of going into the wilderness, having just you and your couple, you got your shotgun against the bears and you've got your fires and you're hauling water, striking out on your own and making a new civilization, that was consciously part of how they thought about this at the time.

The question of Thoreau and the transcendentalists is so interesting to me because the 70s generation, they didn't themselves look back to the 1840s pretty much at all. I mean, Thoreau, they did, they would romanticize Thoreau and were really interested in his kind of romantic relationship with nature, they liked that he was a war resister, they liked that he was kind of a curmudgeon, but they didn't go read about Brook Farm or Fruitlands or the other kind of experiments that were happening then and that didn't think of themselves as being part of that American tradition. They thought they were doing something brand-new and inventing it for the first time, and that was actually more their self-conception. The more I read about the 1840s and the transcendentalist time period, the more resonances I see with the 70s. It was one of the time periods where the cyclical back to the land movements that have happened throughout American history and I think we are in another one now.

CURWOOD: The more things change, the more they stay the same, huh?

Kate Daloz reads from her book at a bookstore in Brooklyn. (Photo: Public Affairs Books)

DALOZ: Yeah, I'm now wondering in this current generation of back to the landers, do they see a link to the ’70s? I do but I don't know if they do. The ’70s generation helped develop organic practices and natural food systems and co-ops, and all of these systems that are in place to kind of give the general public access to stuff they didn't have access to in 1962. They had in 1972, but didn't have it in 1962 and we have it today, and so I'm wondering, I see that sweep that people who grew up today taking crunchy butter and yogurt as for granted in a supermarket where I can see that happened I started as a result of these experiments in the ’70s but I'm wondering if the people today who are going back to the land think of themselves as being part of a tradition that includes the ’70s or not. I don't know the answer but I want to find out.

CURWOOD: What do you think is most important thing we can learn from the back to the landers who try and try and who, well, don't always necessarily succeed?

DALOZ: I've been thinking about that so much and what I really admire about the mindset of the people who did this is they just thought they could do it. They let themselves invent and they let themselves discover and they let themselves struggle along the way and I really appreciate just sort of the attitude of putting yourself in a situation and figuring it out and inventing something new along the way.

CURWOOD: Kate Daloz is the author of We Are As Gods: Back to the Land in the 1970s and the Quest for a New America. She teaches at Baruch College as a freelance writer in New York City. Thank you so much, Kate.

DALOZ: Thank you so much for having me.

Links

We Are As Gods summary and author bio

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth