May 13, 2016

Air Date: May 13, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Exxon, the Climate and Senator Whitehouse

View the page for this story

US Senator Sheldon Whitehouse [D-RI] chats with host Steve Curwood and discusses why he has risen more than 135 times on the Senate floor to alert his colleagues about climate change, and how the pending investigation into ExxonMobil’s alleged climate fraud has a precedent in litigation against the tobacco industry for its civil fraud and racketeering. (12:40)

Senate Energy Bill

View the page for this story

A coalition of environmental organizations that lobbied Congress for years to reform current energy policies now expresses misgivings about a recently passed Senate bill. The Natural Resources Defense Council’s Marc Boom tells host Steve Curwood why he sees provisions like expanding biomass and exploring methane hydrates as steps in the wrong direction. The NRDC endorses some provisions in the bill including measures to expand energy efficiency and protect public lands, but Boom says that on balance the bill could do more harm than good. (08:35)

Gas Boom Goes Bust

/ Reid FrazierView the page for this story

The boom in natural gas released through fracking has bought new business and jobs to many communities, including some in Western Pennsylvania. But now oversupply linked to a mild winter means some of those businesses are going bust, as the Allegheny Front’s Reid Frazier reports. (04:15)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra tells Host Steve Curwood about two occasions when commentators spoke “truth to power”, that resulted in both of them being forced out of their jobs. Then, a look back at a mix-up between Argentine submarines and Right Whales during the Falklands War that turned out badly for the rarest cetaceans. (04:05)

Back to the Land in the Flower Power Era

View the page for this story

In the 1960s and 70s, many idealistic young Americans left cities and suburbs to build their own version of the American dream together on communal farms, often without a clue how to farm sustainably. Kate Daloz, author of “We Are As Gods: Back to the Land in the 1970s and the Quest for a New America”, brings us stories of this movement from the homesteaders who lived near the geodesic dome in Vermont that was her childhood home. (14:15)

King Penguin Chicks Hunger for More

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s resident explorer Mark Seth Lender visited a King Penguin nesting colony on South Georgia Island in the South Pacific. Early whalers called the chicks ‘Oakum Boys’ because their tan-colored coats reminded the sailors of the tarred cotton twine used for caulking. Mark comments on the hunger of the Oakum Boys, as they shed their downy feathers and their parents stop feeding them, so the juveniles can learn to find their own food. (02:05)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Sheldon Whitehouse, Marc Boom, Kate Daloz,

REPORTER: Reid Frazier, Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. A US Senator says a legal probe of oil giant Exxon is justified, as its contradictory climate statements may amount to a public fraud.

WHITEHOUSE: The CEO of Exxon may say nice things at a Davos cocktail party, about climate change being real and Exxon being interested in a carbon price, but down at the American Petroleum Institute, where they lobby, they're telling people, "Don't believe that. You cross us and you're toast."

CURWOOD: We’ll hear Rhode Island Democrat Sheldon Whitehouse. Also, the fracking boom in Pennsylvania helped local businesses boom, too.

EDWARDS: This is mainly the heart of the business, fire resistant coveralls, pants, jeans and workpants, and for the first six months, fabulous, then it just started going down and down and down.

CURWOOD: That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies. innovating to make the world a better more sustainable place to live.

Exxon, the Climate and Senator Whitehouse

Senator Whitehouse represents Rhode Island, the “Ocean State”. Sea level rise is already presenting a threat to the state’s coastal areas including Narragansett Bay. (Photo: Christine Riggle, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Even when there was a Democratic majority in both houses, Congress failed to pass strong measures to address global warming. And since the Republicans took over, the situation has stayed the same, with many in Congress even questioning the science of climate change. But that has not stopped one Senator, Democrat Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island, from taking the floor weekly to address his colleagues on the dangers of climate disruption, and the need to act. Sheldon Whitehouse joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

WHITEHOUSE: Thank you. Good to be with you.

CURWOOD: Why are you so concerned about the climate?

WHITEHOUSE: Well, I'm from the Ocean state, and when you look at the oceans, 90-plus percent of the heat that we captured from all these greenhouse gases has been taken up by the oceans. So they're warming and you measure that with thermometers - it's not complicated to measure - and unless somebody's going to repeal the law of thermal expansion, when they warm they get bigger, and when they get bigger they rise against our shores, and we can measure 10 inches of sea level rise in Newport, Rhode Island, since the devastating hurricane of 1938. And at the same time that they're taking up heat, they're taking up carbon dioxide which chemically - unless you're going to repeal the laws of chemistry - causes them to turn more acid and we now have oceans that are acidifying at the fastest rate in 50 million years. And we can see that our species Homo sapiens has been on the planet about 200,000 years, 50 million is a long long time to go back to for your last example of when oceans suffered this sudden and devastating a change. So if you're from the Ocean state, just that ought to be enough to get your attention setting aside what is happening on the land.

CURWOOD: So why has Congress been unable to pass any climate change legislation?

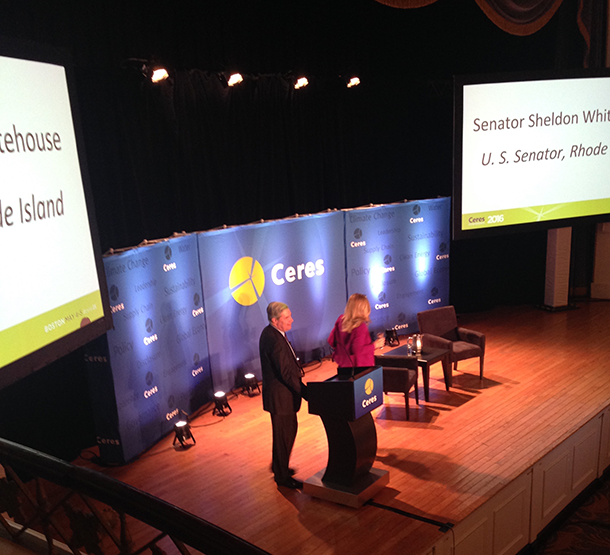

US Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) (left) with LOE’s Steve Curwood. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

WHITEHOUSE: Two reasons: the first is that the fossil fuel industry has an enormous subsidy to defend and they're defending it through a very very powerful climate denial apparatus, and second, the Citizens United decision put unprecedented political artillery into their hands that they have used to murderous effect.

CURWOOD: Climate denial? What about the role of Exxon in this?

WHITEHOUSE: Exxon hss been at the heart of the climate denial operation. The core players are the Koch brothers, Exxon and sort of the lingering group from the tobacco denial operation and they've gotten more sophisticated and multifaceted since then. It almost seems quaint to think that Phillip Morris tried to hide behind the American Tobacco Institute. Now you've got the George C. Marshall Institute and the Heartland Institute and all these other things. So they've become more sophisticated, but it's a very powerful operation, and Exxon-Mobil has been at the heart of it.

CURWOOD: Now, I understand that with Senators Richard Blumenthal, Ed Markey, Elizabeth Warren, you've written to Exxon folks asking them about their financial support for climate denial. How has Exxon responded?

WHITEHOUSE: They have been I think, a little bit shifty about wanting to, on the one hand, extricate themselves from their previous outright climate denial positions, but at the same time they have not been very accountable about closing down the lobby efforts that they make in Congress that are still leaned hard over into full on climate denial. So the CEO of Exxon may say nice things at a Davos cocktail party about climate change being real and Exxon being interested in a carbon price. But down at the American Petroleum Institute where they lobby, they're telling people, "Don't believe that. You cross us and you're toast."

ExxonMobil’s own scientists informed its executives about climate change decades ago, says Senator Whitehouse -- and soon thereafter the company allegedly began funding climate denial efforts. (Photo: Thomas Hawk, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, you're a former prosecutor you were Attorney General for the state of Rhode Island, you were US attorney for the state of Rhode Island, what you make of the investigations by the Attorneys General of New York state, Massachusetts, for the Virgin Islands, into Exxon the question of illegality in their denial.

WHITEHOUSE: Well, there's a precedent for it and a very good one which is the civil lawsuit that the department of justice brought against the tobacco industry for fraud about the dangers of that product, and the interesting news about that is that the Department of Justice won, and the case confirmed the proposition that corporate fraud is not protected by free speech or the First Amendment. Fraud is fraud and free speech is free speech, there is a line between the two, and by and large prosecutors and juries can tell them apart. So the pushback against that you've seen from a lot of the front groups and from that mouthpieces like the Wall Street Journal editorial page just try to reboot that lost argument and it may be something that fools people who are unschooled in this area, but any lawyer knowledgeable about this area knows that fraud is not protected by the First Amendment and the government's entitled to investigate it and if fraud is there, there should be consequences. And there's plenty of smoke around what the climate denial operation did to suggest that an investigation to see whether there's fire is justified.

CURWOOD: Specifically against whom is this alleged fraud being committed?

WHITEHOUSE: Well, it's against the general public. It has the specific purpose of trying to convince people that the question of climate change is unsettled when essentially no responsible scientist or scientific organization would say that. And the ultimate desire is to protect subsidies that the fossil fuel industry gets in the hundreds of billions of dollars by not being accountable for the cost that it causes, and this is a very powerful industry defending its turf basically for economic reasons and to hell with the rest of us. So that's an unfortunate corporate choice by them.

In 2006, Philip Morris was found guilty of civil fraud and racketeering for giving the impression that their Marlboro “light” cigarettes were a safer alternative to regular cigarettes. (Photo: Alejandro Giacometti, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Specifically, the Securities and Exchange Commission requires honesty in disclosures from companies about their activities. In your view as a former prosecutor, what chance is there that Exxon may have violated the criminal part of our statutes?

WHITEHOUSE: It would be think premature to say that, but I do think that Attorney General Schneiderman of New York feels on very solid ground pursuing them under the New York state securities laws for exactly that point. And you can go at it from a number of different ways. One is all the things they said that they knew were true when they knew climate change was a real problem because their own scientists were telling them that, and the other is the financial reporting that they continue to do right now, claiming that trillions of dollars of fossil fuel in the ground is still an asset of theirs, where we all know that if you actually burned all that fossil fuel you would completely wreck human life on this planet as we have known it in our 200,000 years of habitation of the planet. So you kind of can't have it both ways and they're trying to have it both ways, so just the valuations I think raise issue about whether they're being honest with their shareholders.

CURWOOD: So the New York State attorney general is using state investor protection laws. What about the United States attorney general? What about the federal laws really that are much bigger, stronger, and cover everywhere in the US?

WHITEHOUSE: Well, it was the Department of Justice that brought the tobacco litigation. I think the Department of Justice in that case followed a lot of litigation by state attorneys general. So it's not unusual for state attorneys general to take the lead before the Department of Justice is willing to move, but ultimately I think the most compelling event in turning around the public perception about the tobacco companies was when they were found to have committed fraud in a case brought by the United States Department of Justice in a decision by a United States District judge affirmed by the United States Court of Appeals. That's a pretty powerful stamp of validation that these guys were up to fraud.

CURWOOD: And if my recollection is correct it was really a racketeering charge, a civil racketeering charge.

WHITEHOUSE: It was brought under the civil component of the federal racketeering statute.

CURWOOD: I understand you've risen 135 times or more on the Senate floor to talk about the risk and reality of climate disruption.

WHITEHOUSE: A little more, 135 times in the time to wake up series that we've been doing weekly for all the weeks, now four years I think that when the Senate is session I give a speech every week.

CURWOOD: Why do you do this?

Senator Whitehouse has spoken on the U.S. Senate floor more than 135 times about climate change in his “Time to Wake Up” speeches. (Photo: Jeffrey Zeldman, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

WHITEHOUSE: Persistence. Chinese water torture. Droplets of water cut through rock in enough time. You know, it's hard to know what the example is. When I started doing this the Obama administration was refusing to even speak about climate change. The fossil fuel industry had the Republican Party thoroughly locked down in the wake of Citizens United and the environmental community was kind of in despair that Congress was even hearing that this was real. So I thought the least I can do is to like be a sentry out there every single week reassuring people that there's at least one voice that gets this is real, we need to do something about it, it's important, let's go.

CURWOOD: What kind of a difference has it made?

WHITEHOUSE: You know, I don't know. It's hard to assign causation to things but certainly between then and now there's been a huge turnabout in public perception. The Obama administration has engaged in very powerful and helpful ways, and the pressure is such that even fossil fuel company CEOs now know that they've got at least say the right thing about climate change and carbon pricing even if they're telling all their lobbying armies to continue to threaten anybody who crosses them.

CURWOOD: Talk to us about your views on getting a price on carbon. Is this something we should do, how much should it be, how should it get implemented?

WHITEHOUSE: It's absolutely something that we should do. The price on carbon that we have in the bill that I've filed is the price on carbon that the federal Office of Management and Budget has established. It probably should be higher than that but from a point of view of why create unnecessary fights, I'm willing to live with the OMB number. It has a number of values: one is that it's economy wide, it doesn't pick favorites, it doesn't have regulatory cost, or has very low regulatory cost. You can protect at the borders for trade with companies that don't have a similar one, and you can ramp it up and down as we meet or don't meet the goals that we have to protect the planet for more than a degree and a half of temperature increase.

CURWOOD: So, how much more time do we have left to get this right?

Senator Whitehouse recently spoke about the need for industry lobbying on climate change at the Ceres Conference 2016 in Boston, “Business Not as Usual: Sustainability in an Age of Disruption”. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

WHITEHOUSE: The slightly scary part of this is that we don't know. That we just don't know what tipping points are going to emerge and what points of no return we're going to pass. We might not recognize them until they happen, so we really need to proceed with all deliberate speed, and with a sense of urgency and mission to get this done because if we don't, we grew up looking at the group, that won the second world war as the greatest generation, our grandchildren will look back at us as a particular loathsome and shallow generation that just succumbed to the greed of a very small group of people because they were politically powerful and that would be a very unfortunate legacy.

CURWOOD: Before you go, Senator, this is the election season. In your view, if the Republicans take the White House, what are the odds of seeing climate progress, what are the odds of seeing say Exxon prosecuted for its alleged fraud here?

WHITEHOUSE: The odds of Republicans doing anything on climate I think are substantially less than of Democrats just because the way that the fossil fuel industry has operated in this has been basically to conduct a hostile take over of the Republican party and run out Republicans who disagreed with them and put their thumbs on Republicans generally. So it would be hard for them to undo that, but I would say even though that is the case, the public pressure, the scientific pressure, the facts that are emerging in senators' home states are creating an irresistible force that even that pressure ultimately can't stop. All it can do is slow it down. But like we were saying earlier, time is not our friend. It matters whether we get there sooner rather than later.

CURWOOD: Sheldon Whitehouse is the Democratic Senator from Rhode Island. Thank you so much, Sir.

WHITEHOUSE: Great being with you. I really appreciate the opportunity. Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Senator Whitehouse’s “Time to Wake Up” speeches on climate change (136 and counting)

- InsideClimate News: “Exxon and Its Allies Invoke First Amendment to Fight Climate Fraud Probes”

- On Big Tobacco’s conviction of fraud and racketeering in 2006

- About Senator Sheldon Whitehouse

[MUSIC: Gontiti, “The Syncopated Clock,” Magic Wand of Standards, Leroy Anderson, Pony Canyon Records]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...it's good, it's bad, it's even ugly activists say about the Senate Energy Bill both good and bad. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from Wunder Capital, an online investment platform that allows individuals to invest in solar projects across the U.S. More information and account creation at Wunder Capital.com That's Wunder with a 'U'. Wunder Capital, Do well and do good.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: No Strings Attached, “March Of the Picnic Ants,” No Strings Attached, Folk Era Records]

Senate Energy Bill

Methane ice worms inhabit a white methane hydrate. The frozen methane deposits on the ocean floor could be a source of energy, but NRDC says developing this potential resource would open a dangerous can of worms for the climate. (Photo: NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Gulf of Mexico 2012 Expedition, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. A bipartisan majority of 85-12 in the US Senate has approved a broad energy reform bill that includes funding for clean energy research and conservation. The House has already passed its version, and assuming both chambers can iron out their differences in conference committee, America is poised to get its first major energy legislation in almost a decade. But a coalition of environmental groups that includes the Sierra Club, the League of Conservation Voters and the Natural Resources Defense Council says what’s on offer is a mix of good and bad. Marc Boom of the NRDC joins us now. Marc, welcome to Living on Earth.

BOOM: Thanks, Steve. Great to be here.

CURWOOD: So, there's good news and there's bad news in this bill. Let's talk about, Mark, what in your view was not so great about this from an ecological standpoint.

BOOM: Sure, so there's lots of celebrating on Capitol Hill right now because this was a bipartisan bill and the first energy bill to get through the Senate since 2007, and while there's lots of good provisions on energy efficiency and renewable energy and land conservation, unfortunately, there are some provisions that were added to the bill that are going to undermine our progress on climate change and harm other environmental protections.

CURWOOD: Alright, so let's break those down. So what are the harms for climate change?

BOOM: I think the first thing that I want to talk about is this provision that was added which would define biomass as carbon neutral. The latest science shows that forest biomass is definitely not carbon neutral especially in the time periods that we need it to be in order to address climate change.

CURWOOD: Well, the conventional wisdom is, “look, you burn a tree but you plant a tree.” So, what's the problem?

BOOM: It is sounds great, but when you really get into the science you seeing that in order to make sure that you regrow the trees, there's a lot that needs to happen and in the meantime all of that carbon is up in the atmosphere heating up the climate, and so the trees might regrow in decades or potentially a century. That's way too long for what we need to do to act on climate change.

Biomass would be recognized as “carbon-neutral” under a provision in the bill, and Marc Boom says that ignores the fact that carbon dioxide released from biomass energy production may take decades to be re-absorbed by growing trees. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

It's also problematic because this is an example of Congress usurping the role of EPA and of scientists who have the authority to develop methods for determining how carbon intensive a certain fuel is. Congress just declaring it goes around that process and is going to create real problems in the future. And one of those could be that when states are developing their plans to comply with the Clean Power Plan, they might rely more on forest biomass than sources such as solar and wind which are much cleaner.

CURWOOD: What are some of the other provisions of this bill that you think are less helpful for climate protection?

BOOM: So, there's a provision that would allow new research and development into methane hydrates, basically, like frozen natural gas that is located under permafrost and on the sea floor, and the latest science shows that there is probably more methane hydrates than all the current known fossil fuels that we have. So the fact that the bill is spending $175 million to help commercial interests develop drilling and extraction technology to harvest this is very problematic. We need to be moving away from fossil fuels, not unlocking new sources of it.

CURWOOD: What concerns do you have about the hydrates? I've heard that some say that you know that they're just barely below freezing down there, there is quite a bit of methane there and poking around at them might result in the so-called methane "burp" and then might and releasing huge amounts of the methane. To what extent are you concerned about that?

BOOM: That's definitely one of the concerns. They haven't developed the technology to efficiently extract it, so it's not clear how they do that without destabilizing these formations and allowing that methane as it depressurizes to rise into the atmosphere. As you and I both know, methane is a very potent greenhouse gas, especially in the short term, so unlocking these could definitely release methane into the atmosphere. It also has the potential to destabilize the sea floor, and that is very detrimental to the marine environment. Furthermore, just to find where these hydrate deposits are, they need to use acoustic seismic surveying and that includes the use of high-pressure air guns that when they go off can be heard over hundreds of square miles and damage marine mammals like whales and dolphins and also disrupt commercial fisheries.

They say it’s not all bad: environmental groups applaud measures in the bill that support renewable energy like wind, solar, and emerging technologies. (Photo: Green MPs, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, it sounds like you think this methane hydrate provision is a lot of bad news. What are some of the other provisions of the bill that you don't particularly like?

BOOM: Well, there's provisions in the bill that speed up the environmental review on mining and gas and oil drilling and on reviewing liquid natural gas export facilities. Fundamentally rethink that these types of reviews need to be done right and setting an artificial deadline on when they should be completed leaves lots of questions unresolved and could end up with new infrastructure that harms communities and the environment and those committees might not know what those impacts will be.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about what you see as good incentives in the bill from an ecological standpoint.

BOOM: I mean the bill is built around a really solid core of expanding energy efficiency and renewable energy, great innovation and land conservation. It really builds upon this piece of legislation known locally as the Shaheen-Portman energy efficiency bill from Senator Shaheen from New Hampshire, a Democrat, and Senate Portman from Ohio, a Republican. This has been a bill that has been around for several years, almost passed many times, but every time it came up before it was really a lightning rod to attract really troubling anti-environmental provisions. It promotes energy efficiency in buildings, in manufacturing facilities and in the federal government. Kind of low hanging fruit, but you know those are sectors that account for a large amount of our carbon emission, so it's really critical that we make it easy for them to adopt energy efficiency.

There's also provisions on renewable energy. It expands research into marine hydrokinetic and geothermal which are both sources that are largely untapped and could provide some of the baseload power that we need from clean renewables. There's a lot of money that goes into grid innovation. This is going to make it easier to put wind and solar onto the grid and make sure that we can also integrate more storage which increases how effective that wind and solar will be when it's on the grid.

The Senate energy bill includes a measure to permanently reauthorize the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which has conserved many key habitats, including 88 percent of the Sunkhaze Unit in Maine’s Sunkhaze Meadows National Wildlife Refuge. (Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Northeast Region, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, what you're saying here, Marc, there's good, there's bad, there's even ugly. On balance, you folks in the business of advocacy, if this would hit the President's desk what would you say?

BOOM: Well, if the bill went to the desk as it is right now, we don't support that. We really feel that the biomass provision and methane hydrates, environmental reviews being sped up, a couple other provisions like delaying important efficiency standards for furnaces...those need to be resolved because on balance right now it could do more harm than good.

CURWOOD: So, the Senate, of course, is one of two houses there in the Congress and the House already passed its own energy bill late last year. What needs to happen to reconcile these two versions in committee so that there would be something that would be offered to the president to sign?

BOOM: Well, that's going to be an interesting process. The bills are pretty far apart. The house bill didn't have much bipartisan support - I think only nine Democrats supported it, and really is going the opposite direction in that it reverses our progress on energy efficiency, it doubles down on integrating fossil fuels into our electricity grid and has far more damaging provisions on environmental reviews and things like that.

Marc Boom is the Associate Director of Government Affairs at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). (Photo: courtesy of Marc Boom)

One sticking point that I see coming up actually is that the Senate bill includes a really great provision that I didn't get to mention before where it permanently reauthorizes the land and water conservation fund which is one of our most successful conservation programs in the nation. It also includes a new fund to help fix the maintenance backlog at our national parks. The house bill doesn't have these provisions and in fact the chair of the House Natural Resources committee, Representative Bishop from Utah has major concerns with the program and wants to see major changes before going forward. So it's hard to see how that gets reconciled.

CURWOOD: Marc Boom is the Associate Director of Government Affairs at the Natural Resources Defense Council. Marc, thanks so much for speaking with us today.

BOOM: Thanks, Steve, for giving us an opportunity to talk about this.

Related links:

-

“Senate Passes Energy Bill, Looks to Conference With House”

- Letter of concerns about the bill, signed by 10 environmental organizations

- About Marc Boom

[MUSIC: Dr. Michael White, “Give It Up (Gypsy Second Line),” Dancing In the Sky, Basin Street Records (Reissued on New Orleans from Putumayo)]

Gas Boom Goes Bust

A Pennsylvania natural gas well (Photo: WCN 24/7, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: The catastrophic wildfires raging in the tar sands region of Canada have helped push up the price of oil in recent days, as companies there have been forced to stop operations. But natural gas prices in the US have slumped as the mild winter created an oversupply. Some companies drilling in Pennsylvania have laid off workers and shut down operations. That means big changes for some local economies. The Allegheny Front’s Reid Frazier has the story.

FRAZIER: At Jerry Lee’s Emporium in Waynesburg, Pennsylvania, there’s a handwritten sign on the front door.

EDWARDS: Store closing for good.

FRAZIER: Jerry Lee Edwards opened the store in 2014. He came from southern West Virginia to tap into Pennsylvania’s booming Marcellus shale industry to sell clothes.

EDWARDS: But this is mainly the heart of the business, fire resistant coveralls, pants, jeans and workpants.

FRAZIER: Before coming to Waynesburg, Edwards had sold his wares to coal miners in West Virginia, but that industry was suffering, so he moved north to Pennsylvania. Business was good for a few months.

EDWARDS: For the first six months, fabulous, then it just started going down and down and down.

Jerry Lee Edwards, 73, sits in his Waynesburg, Pennsylvania store, where he sold work clothes to natural gas workers. His business, which is closing this spring, is one of the casualties of the slowdown in Pennsylvania's once booming natural gas industry. (Photo: Reid Frazier)

FRAZIER: Business got so bad, Edwards decided to close his shop this spring. A lot of others who have tied their fortunes to the fracking industry are having to make similar recalibrations. Low natural gas prices have led fracking companies to slash budgets and lay off workers; state records show Pennsylvania lost ten thousand jobs in the industry.

And it’s having an impact. Robbie Matesic is head of economic development for Greene County, one of the biggest drilling areas in the Marcellus Shale. Sitting in her office in downtown Waynesburg, she said the difference between now and a few years ago is audible.

MATESIC: My goodness in 2010, and in 2011, we wouldn't been able to have this conversation here so close to the street ’cause it just was constant traffic.

FRAZIER: Matesic said when the boom started about five years ago, there was an influx of workers into the county.

MATESIC: All of a sudden we saw most of the traffic that went thru this town was from Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, Colorado, Utah.

FRAZIER: The county benefitted from that activity. It’s gotten millions of dollars in drilling fees that have gone toward roads and bridges, sewers, and social services.

Matesic said locals also got jobs, with businesses that supplied the drilling rigs and pipeline crews. Restaurants and hotels were also full. And savvy local businesses began catering to oil and gas workers as they passed through.

KOVACH: We have six spots down here at the bottom…

Jerry Lee Edwards stands in his once-thriving clothing store in Waynesburg, Pennsylvania. He plans on closing the store this spring after the slowdown in the natural gas industry. (Photo: Reid Frazier)

FRAZIER: Joel Kovach manages Rohanna’s Golf Course just outside Waynesburg. About five years ago, Rohanna’s added an RV park. The company cleared a patch of roadside and put in hookups for 30 RVs to cater to oil and gas workers. The spaces filled up. And for a while, they had a waiting list.

KOVACH: I’d say it was at least 10 to 15 spots deep. Those people needed place to stay.

FRAZIER: Today, only 8 of the 30 RV spots are filled. The rest of the lots stand empty.

KOVACH: It's been like this for probably 6 to 9 months now, to where there's not too many people.

FRAZIER: Kovach thinks business will pick up again in the future. As for Edwards, the shop owner who is closing up, he doesn’t think he can wait that long.

EDWARDS: They say it'll come back in two or three years. I'm 73 years old, I'm not waiting 2 or 3 years for it to "maybe" come back.

FRAZIER: He’s actually heading to the U.S. Virgin Islands, where he’ll work as a music promoter. It’s not a bad fallback. But for those sticking around in Greene County, most are getting used to what looks like the end of the boom times. I'm Reid Frazier.

CURWOOD: Reid Frazier eports for the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Listen to the original story here

- More Pennsylvania environmental stories from the Allegheny Front

[MUSIC: Dr. Michael White, “Give It Up (Gypsy Second Line),” Dancing In the Sky, Basin Street Records (Reissued on New Orleans from Putumayo)]

Beyond the Headlines

The HMS Brilliant in 1985. (Photo: U.S. Navy/Lt. David Parsons, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: Time to see what’s going on beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra now.

He’s with DailyClimate.org, and Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and joins us from Conyers, Georgia. How are things, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Steve, I have two stories of two very different commentators who both spoke truth to power, and they’re now both unemployed. Rick Friday’s the first one. He was an editorial cartoonist for Farm News, a weekly publication that reaches about 24,000 farm homes in Iowa. Al that came to an end when one of his cartoons caused what his editor said was a “manure storm.”

CURWOOD: Peter, I don’t think he said really, “manure storm,” did he?

DYKSTRA: Oh no of course he didn’t say that but I don’t think I’m allowed to say what kind of storm he really said it was, so I picked the most agriculturally accurate substitute. Mr. Friday says he was told he was fired after twenty-one years and over a thousand editorial cartoons when he published a cartoon lamenting the three Big Ag CEOs from Monsanto and DuPont Pioneer (those two of the giants in the seed business) and also the CEO of John Deere, the farm equipment manufacturing giant — have a total salary bigger than that of two thousand Iowa farmers.

CURWOOD: And how did this - er - manure storm play out?

The cartoon that got Rick Friday fired, and his Facebook reflections about the incident.

DYKSTRA: Well Friday says he was told that a major seed distributor cancelled its advertising in response to the cartoon — Monsanto says it’s not them and the owners of Farm News aren’t talking to anyone about this — but Rick Friday isn’t the only journalist with some strong views who’s suddenly looking for work.

CURWOOD: Oh really, Who else?

DYKSTRA: Well one of the most respected writers on conservation and nature in the American West is out of a job. Author Terry Tempest Williams resigned her longtime teaching position at the University of Utah in late April after what she describes as an attempt to push her out of teaching.

CURWOOD: So what’s going on, what’s the issue here?

DYKSTRA: She wrote a resignation letter and I must say, it’s very well-written for a resignation letter. Terry Tempest Williams said she was subjected to what she called a “humiliating” set of bureaucratic demands and an offer of a phased-in retirement that she never asked for. One of the demands, she said, was that she stop taking her students out to see the nature she’s teaching about and she should stick to teaching on campus and in the classroom just like all the other professors.

CURWOOD: Okay Peter, what’s the back-story here?

Tension between Terry Tempest Williams and University of Utah administrators arose over her experiential, outdoor teaching style. (Photo: Edgar Zuniga Jr. Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well there quite possibly is a back-story — in February, Williams took part in a protest against oil and gas lease sales on public lands in Utah. She and her husband also dropped about $1,700 to buy drilling rights on eleven hundred acres of land near Arches National Park. Yeah, that’s right, you can still buy drilling or mining rights on Federal land in the West for about the price of a small bag of Doritos per acre. She also wrote an op-ed in the New York Times describing the process and urging us all to keep fossil fuels in the ground.

CURWOOD: So Peter who, if anyone, is anyone making the suggestion that maybe Terry Tempest Williams was forced out because she angered the oil and gas industry?

DYKSTRA: Well actually University officials say that’s not the case and they weren’t trying to force her into early retirement. But in that resignation letter, Williams said the University found her teaching about nature to be “threatening.”

CURWOOD: Oh my goodness. The higher laws of nature huh, under attack. Hey, what do you have from the history vault for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well I brought an urban myth that turned out to be probably true, and it’s kind of a yucky one at that.

CURWOOD: Oh, please not now.

DYKSTRA: Well in the brief Falkland Islands War between Argentina and the UK in 1982, the British Navy was on the lookout for small, Argentine submarines. Unfortunately, on sonar, small submarines have a signal that’s a lot like a large whale. Rumors spread that Her Majesty’s Navy was torpedoing southern Right whales, erroneously thinking they were armed to the teeth with a belly full of Argentine sailors. Then ships’ logs, particularly the one from the skipper of a frigate with a possibly inappropriate name – the date on this was May 12, 1982 – and some other items confirmed this years later, but no one knows exactly how many whales got blown up this way.

CURWOOD: Peter what’s the inappropriate name of the boat?

DYKSTRA: The H.M.S Brilliant.

CURWOOD: Oh indeed huh? Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health news that’s EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org — thanks Peter — we’ll talk to you next time.

DYKSTRA: Alright Steve thanks a lot, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- Rick Friday’s Controversial Cartoon

- Terry Tempest Williams’s Resignation Story And Resignation Letter

- Terry Tempest Williams NY Times Op-Ed

- HMS Brilliant History

- The Daily Climate

- Environmental Health News

[MUSIC: Joshua Rifkin, “Nove De Julho,” Rags & Tangos-Ernesto Nazareth, James Scott, Joseph F. Lamb, Ernesto Nazareth, Decca Eloquence]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the glory and grime of getting back to the land a generation ago. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Topsy Chapman and the Pros, “Baby, Won’t You Please Come Home,” My One and Only Love, Clarence Williams/Charles Warfield (public domain), GHB Records (Reissued on New Orleans from Putumayo)]

Back to the Land in the Flower Power Era

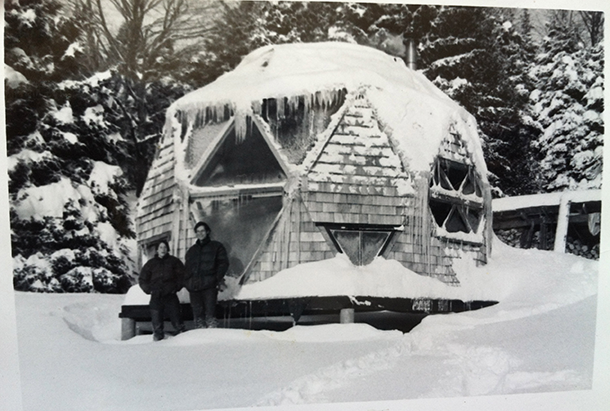

The author’s parents, Larry and Judy, in front of her childhood home, a geodesic dome inspired by the dome erected at the Myrtle Hill commune. (Photo: courtesy of Kate Daloz)

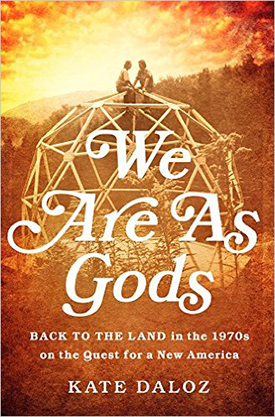

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. As interest in sustainable, organic food has grown, so have the numbers of young entrepreneurs taking up farming to grow crops to sell directly to restaurants and at farmers markets. But that kind of movement is hardly new. Back in the 1960’s and 70’s thousands of idealistic young people left the city and went back to the land, looking to live sustainably and often communally. Now a new book captures that idealism: "We Are As Gods: Back to the Land in the 1970s and the Quest for a New America." It’s written by Kate Daloz, who teaches at Baruch College. It chronicles that era of communes and hitchhikers and recalls some homesteaders who lived over the hill from the geodesic dome that was her childhood home. Kate, welcome.

DALOZ: Thank you so much.

CURWOOD: What was motivating people back in the late ’60s, early ’70s to go back to the land to live and work on communal farms?

DALOZ: So, in addition to all of the political upheaval happening in the country as a whole, there was a really strong feeling at that time of wanting to rebel against the conformity of a ’50s childhood, and for a lot of people, they didn't want the same kind of two parents in the suburbs by themselves, so they really sought that out by going together - in a lot of cases to the country. They wanted to build their own houses, they wanted to grow their own food, and they wanted to learn skills that they didn't feel they had access to. They needed each other and so they went together because in the early days especially they needed a whole group of people to kind of make that experiment. To me, that's - was a really interesting reason why the communal movement and the back to land movement dovetailed in this period.

Loraine, the “heart and soul” of the Myrtle Hill commune, sits cross-legged in a field of sunflowers, 1970. (Photo: Fletcher Oakes)

CURWOOD: And they were drawn in by this book by Helen and Scott Nearing right? "Living the Good Life" they called it.

DALOZ: Yes, there had been this earlier communal movement that kind of was leading lots of people into communal houses in the rural areas and then the Nearings book was reissued and a whole new generation, a whole new round of single family homesteaders was inspired to kind of do the same thing.

CURWOOD: Good thing they didn't know how hard it is to farm, huh?

DALOZ: Yes, they really didn't. And that was another thing, the naïveté about what it would take to really live what they thought of at the time as a simple life, and you know, it involved less commercial goods but hauling water by hand, you know cutting your own firewood, none of that is simple. It's incredibly difficult. And the number of people, my parents included, who just talked about how many hours it took in a day to just make dinner or just heat your house. So they were surprised by that, but they want a lot from it too.

CURWOOD: The cover of your book has, I think it's a picture of your parents sitting on the scaffolds of the geodesic dome. What's the story behind that dome?

DALOZ: Yes, those are my parents and that is the house that I grew up in. My parents, Larry and Judy, had been in the Peace Corps. My dad had a very profound revelation at one point. He was in a village and realized he was the only person in the village at the time who didn't know how to build a house and didn't know how to get his own clothes, and he had a doctorate at that point. He suddenly was horrified to realize that for actually living day to day and surviving he was useless. My mother wanted the opportunity to do things that she had been told as a girl she wasn't capable of doing, so she wanted to build a house, she wanted to sort of have that freedom to test her own strength.

Neither of them had ever built anything before, so they knew they had to build something idiot proof and they heard about the dome at the commune Myrtle Hill, and they just were blown away by the beauty of it, and someone there lend them a book. It was Lloyd Kahn's “Domebook 2” and they just followed the instructions and minutes before that picture is taken they were convinced it wasn't going to work. It looks like Tinkertoys and then you put it together, it's very floppy, and then at the last second when you put that final bolt in, suddenly it becomes unbelievably strong and so that picture was taken by my aunt basically minutes after they've finished this dome structure and realized actually they were to be able to pull it off after all.

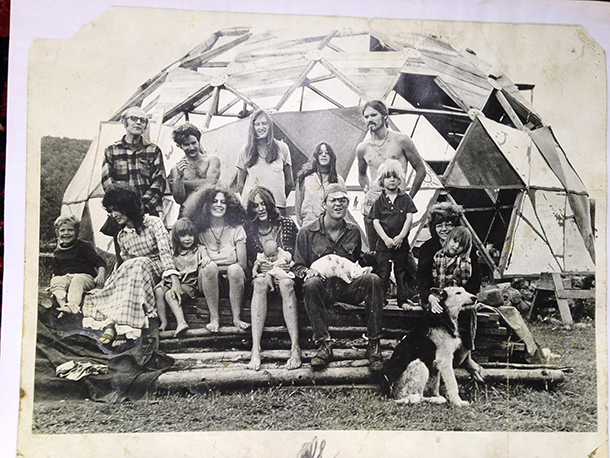

The Myrtle Hill communards and friends proudly gather in front of a geodesic dome in the summer of 1971. (Photo: courtesy of Kate Daloz)

CURWOOD: Now, talk to me about the farms and communes that you wrote about. Characterize them for us please.

DALOZ: One is called Myrtle Hill, and that was sort of your prototypical hippie commune and they would say that too. Twenty young people, they moved to an absolutely undeveloped former potato field and built from scratch their own house. They made decisions communally, they had all of their finances were pooled together. That was sort of the expectation, that everybody would share what they had. It was this intense intense experimentation socially and also just in the daily living.

The other commune I write about, Entropy Acres, they would actually only call themselves a semi-commune, which I think is fair. It was two couples, but they were both monogamous. They were living together kind of pooling resources and they were committed to farming without any combustion engines. So they used horses and they started a very early organic carrot farm, and their learning curve was immense, and then they also had unexpected twins, newborn twin babies, and so it was four adults and two newborn twins living in a house trying to farm without using any combustion engines at all.

CURWOOD: No fossil fuels...they sound a bit Amish to me.

DALOZ: I think they kind of wished they were. You know, it's interesting. The back to the land movement in a way had that same idea of the Amish kind of...they were really interested in the sort of 19th century technology, and the Amish Communities that still existed and exist today, in the 70s actually were a huge resource for suburban middle-class hippies that were trying to learn how to do the same thing.

CURWOOD: You know, people living in farm communities have generally been there for generation after generation after generation, and they learn when you're supposed to plant, how you can fix this kind of fence. How did these folks cope without that kind of history?

DALOZ: That's a great question. Well, one of the ways they did it was they went straight to those locals who had done it for generations at least in Vermont, but I'm hearing this in New Mexico and Oregon and other places as well. Really, for a lot of back to the landers, one of their huge resources were exactly does families who have been there for generations and did still remember those skills, and so they asked their neighbors and their neighbors had been watching them usually and thinking, “what is going on over there?” And in the case of Entropy Acres, the horse-farming commune that I write about, they were very lucky to have a local farmer named Luden Young, and he was really committed to making sure that they were safe. He saw that they didn't really know what they were doing and he came over and made sure that they had cleaned their chimney properly so that they wouldn't have a chimney fire with babies in the house. And so in turn, the people at Entropy Acres looked for a way to help Luden whenever they could, and when his barn burned down, they organized a barn raising to which they invited all the local hippies, including my parents, including people from the commune to help him build his barn again. So in a lot of places there was a kind of reciprocity of knowledge, so that's one huge huge huge source for a lot of back to the landers.

The creators of Entropy Acres, the second farming community explored in We Are As Gods, relied on 19th century technologies for their livelihood. (Photo: Fletcher Oakes)

CURWOOD: Please talk to me about some of the major issues that pop up when the groups of people in your book start living communal lifestyles. What are their successes, their failures?

DALOZ: I think the successes and failures, in some ways it seems completely obvious in retrospect, especially anyone who has ever had even just one roommate or two roommates can predict, you know, “who's going to do the dishes? what's the standard of cleanliness that we're going to keep?” and we’re talking about very often places that were committed to no electricity, and no running water, people who started out thinking, “oh, the way we'll form a non-suburban kind of community is we'll all live in one big house together and it'll be great!” and then they found out you know what, actually privacy that's not such a bad idea after all. Or just parenting with two people...that's hard enough without having it be 20 people who are not related to children. I heard from a lot of communards that they hit a turning point in their commitment to a commune when they saw other members of the community reprimand their child in a way that was not how they would do it.

CURWOOD: That is, if they knew who the parent was or who the dad was in some of these communes.

DALOZ: Yeah, I mean in most places I think there wasn't much question about parenthood. On one of the communes I write about, it is true, one of the main characters in the book Lorraine she deliberately made it impossible to know who is the father of her baby. This is a way of symbolically smashing the nuclear family structure.

CURWOOD: Tell me, how did that work out for her?

DALOZ: The part where she wasn't wrong was that the other women in the commune, the other mothers in the commune really were committed to taking care of each other's children. A thing nobody really foresaw was that in the first winter and then actually to be frank in a second winter also, all of the men left. In each of those winters, there's only one man who stayed and all of the rest of the people who were overwintered in the commune were women and children. And I think that they hadn't really foreseen how trying to find a place where there would be total freedom would mean that some people would exercise their total freedom by leaving.

CURWOOD: What happened to Lorraine? How did she succeed in building a new life without electricity and working 9 to 5 or being know like Mrs. Cleaver on "Leave It to Beaver"?

DALOZ: She really was the heart and soul of Myrtle Hill. She was there from the beginning and she was there until the end, and because she came from Vermont, she had a lot of skills that other suburbanites lacked. She was the only one who knew how to build a fire in a woodstove and things like that. She, like the other women in the commune - you know, this is the early seventies, it's right before the feminist movement - they accidentally kind of fell into very rigid gender roles. They did not mean to. They were thinking of themselves as very radical but at Myrtle Hill like a lot of other places, the women ended up doing a lot of the cooking and cleaning. Once they built the house and and it had an indoor kitchen, she became a very committed cook even after she left the commune - or after the commune kind of moved on. She was a cook and a baker for the rest of her life.

CURWOOD: So, Amy, she's another really strong woman in your book. How does her strength come out in the stories that you tell about her?

DALOZ: Amy was one of the people who I just loved interviewing the most. She had a terrible home life. She was the victim of terrible abuse at the hands of her stepfather and basically escaped, really just escaped and found her way to Vermont where she ended up in a commune called Johnson’s Pastures that had a lot of teenagers and they actually suffered a horrible fire in middle of the night that ended up killing four of the communards and Amy jumped out the window and escaped with her life and after that she happened to meet the people at Myrtle Hill and ended up with them and she will say to this day that they saved her life and they gave her a safe place to go from being a teenager to being a young adult. You don't usually think of a hippie commune as being a place that you find stability but she really did.

We Are As Gods: Back to the Land in the 1970s on the Quest for a New America is Kate Daloz’s first book. (Photo: Public Affairs Books)

CURWOOD: Hey, how do you think people in the back to the land movement compare to today's modern homesteaders here? Differences between now and then?

DALOZ: If I have to make a blanket statement, people who are throwing themselves into farming and homesteading experiments today, they don't seem to be quite as naïve about, like, the realities of a cash economy, for example, I mean it was very surprising to me the number of back to the landers who really thought they could just walk away from a cash economy and were kind of shocked to realize that it's not that fun to be cold and impoverished and living under these austere conditions and I don't get the impression that people aren't thinking about how they’re going to make a living once I get back to the land in the way that that the 70s generation - they just left and just went back there and figured it out when they got there.

CURWOOD: Of course times are much harder now than in the 60s and 70s. It didn't take much to get by financially then. Today, it's much harder.

DALOZ: Yes I think that's true, and I think also this baby boom generation, post-war generation, they really had a lot of confidence in the power of a college education. If you were college-educated or you were on that track to be college-educated, they were pretty confident that you could find a good job, so they weren't worried about walking away from that track and then going back to it later. And in fact, they turned out to be right and I'm not sure that my generation I don’t think had that same confidence and people younger than me even less so I think.

CURWOOD: So, how you see these folks that you wrote about in a sweep of American history, reaching back to Thoreau, for example, and coming forward now to today.

DALOZ: They have such an interesting place in history because while they thought of themselves as rebelling against a certain definition of America, what they did was so deeply American that they thought of themselves as pioneers in a lot of case, that romantic western history was absolutely part of a self conception especially in the early days but really throughout this idea of going into the wilderness, having just you and your couple, you got your shotgun against the bears and you've got your fires and you're hauling water, striking out on your own and making a new civilization, that was consciously part of how they thought about this at the time.

The question of Thoreau and the transcendentalists is so interesting to me because the 70s generation, they didn't themselves look back to the 1840s pretty much at all. I mean, Thoreau, they did, they would romanticize Thoreau and were really interested in his kind of romantic relationship with nature, they liked that he was a war resister, they liked that he was kind of a curmudgeon, but they didn't go read about Brook Farm or Fruitlands or the other kind of experiments that were happening then and that didn't think of themselves as being part of that American tradition. They thought they were doing something brand-new and inventing it for the first time, and that was actually more their self-conception. The more I read about the 1840s and the transcendentalist time period, the more resonances I see with the 70s. It was one of the time periods where the cyclical back to the land movements that have happened throughout American history and I think we are in another one now.

CURWOOD: The more things change, the more they stay the same, huh?

Kate Daloz reads from her book at a bookstore in Brooklyn. (Photo: Public Affairs Books)

DALOZ: Yeah, I'm now wondering in this current generation of back to the landers, do they see a link to the ’70s? I do but I don't know if they do. The ’70s generation helped develop organic practices and natural food systems and co-ops, and all of these systems that are in place to kind of give the general public access to stuff they didn't have access to in 1962. They had in 1972, but didn't have it in 1962 and we have it today, and so I'm wondering, I see that sweep that people who grew up today taking crunchy butter and yogurt as for granted in a supermarket where I can see that happened I started as a result of these experiments in the ’70s but I'm wondering if the people today who are going back to the land think of themselves as being part of a tradition that includes the ’70s or not. I don't know the answer but I want to find out.

CURWOOD: What do you think is most important thing we can learn from the back to the landers who try and try and who, well, don't always necessarily succeed?

DALOZ: I've been thinking about that so much and what I really admire about the mindset of the people who did this is they just thought they could do it. They let themselves invent and they let themselves discover and they let themselves struggle along the way and I really appreciate just sort of the attitude of putting yourself in a situation and figuring it out and inventing something new along the way.

CURWOOD: Kate Daloz is the author of We Are As Gods: Back to the Land in the 1970s and the Quest for a New America. She teaches at Baruch College as a freelance writer in New York City. Thank you so much, Kate.

DALOZ: Thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- We Are As Gods summary and author bio

- The Boston Globe reviews We Are As Gods

- Kate Daloz talks about her new book

[MUSIC: Entrain, “Dancin’ In the Light,” A Cape Cod Sampler, I. Major/ J. Fuller, Cape Corps]

King Penguin Chicks Hunger for More

A King penguin parent has no more food to offer its “Oakum Boy” chick (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Way down in the south Atlantic, it’s been nesting season for penguins, and Living on Earth’s resident explorer Mark Seth Lender had the chance to experience this first hand. On the remote shores of South Georgia Island, he found King Penguins and saw for himself a distinction between adults and juveniles. They look so different, that early observers thought they were distinct species, indeed whalers called the babies “Oakum Boys”, for their tan-colored coats that reminded the men of the tarred cotton twine used for caulking. Here’s Mark’s essay.

It’s the time of the season for penguin chicks to molt their soft, downy brown feathers (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

The Oakum Boys

King Penguins

Gold Harbor, South Georgia Island

© 2016 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

[SOUNDS OF PENGUIN COLONY]

LENDER: The Oakum Boys stand in a huddle, hanging around, hanging around, whistling for their supper. Their King Penguin Mothers and King Penguin Fathers have business of their own, standing around standing around, waiting for new feathers. Like curled fall leaves, like peach-colored snow, tiny worn-out plumes litter the ground washing down in rivulets on to the sand, into the sea. Land bound in their state of near undress, the mothers and the fathers cannot follow. The high wee whistling of Oakum Boys will continue for a while. For this is the time of fasting.

[YOUNG PENGUINS WHISTLING]

Here, or there, Oakum Boy’s persistence earns a meal. Late-molting King Penguin Father or early molted King Penguin Mother files through the surf, returning with a crop full: squid and little lantern fishes that glow and rise from the deeps in the dark of the Southern Ocean. Lucky the Oakum Boy with her hunger at the right time, right… there: She pecks her Penguin Father’s or Penguin Mother’s bill and stretches high as she can. And the meal comes up, the long parenting mouth grasps around; the meal goes, straight on down, and baby hungers for more -

An Oakum Boy succeeds in getting a rare meal (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

- There will be no more. Not ever.

The Mothers and the Fathers are all done. The long weeks have begun of no food for self, or other. They tap-tap-tap the Oakum Boys on their brown downy heads: Enough is enough they say. And the mothers and fathers lean away. For the Oakum Boys are changing, exchanging down for feathers; and the only sup will be that they garner on their own, now, and forever.

[PENGUIN COLONY SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: Mark recorded these hungry Oakum Boys and their royal mothers and fathers on South Georgia Island -- and to see his portraits of the chicks snagging a meal, waddle your way to LOE.Org.

The Oakum Boys chicks stand around waiting for a meal that won’t come (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Related links:

- About King Penguins and their “Oakum Boys” chicks

- Mark Seth Lender’s website and story about The Oakum Boys

[MUSIC: Entrain, “Dancin’ In the Light,” A Cape Cod Sampler, I. Major/ J. Fuller, Cape Corps]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Peter Boucher, Adelaide Chen, Jaime Kaiser, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

Special thanks this week to One Ocean Expeditions.

You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth