Trees On the Move

Air Date: Week of May 26, 2017

White pine forest in Pennsylvania. Conifer species including the white pine, Pinus strobus, tend to be moving north as the Eastern U.S. warms. (Photo: Nicholas A. Tonelli, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

The big old oak in your backyard might be solidly planted in place, but its acorns can travel. New research finds that, as the planet warms, seeds of many tree species in the Eastern U.S. are migrating, with pines and spruce heading north while oaks and maples are heading west of their historical ranges. Climate disruption with changes in temperature and precipitation are major causes, Professor Songlin Fei of Purdue University tells host Steve Curwood this rapid shifting of species ranges could change forest communities.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Yes, we have another tale of trees, trees that are moving, though not as dramatically as the Ents in the Lord of the Rings epic. And not individual trees of course, but species that are migrating. A newly-published study confirms that 86 tree species of the Eastern U.S. are moving as the planet warms. But not just north: some are heading west. Songlin Fei of Purdue University is the lead author of the new study and joins me now. Professor Fei, welcome to Living on Earth.

FEI: Well, thank you, it’s very nice to be here.

CURWOOD: So, tell me what's going on here? The Northward shift is not so surprising, since that's mostly having to do with temperature and climate change certainly is warming things up, but why are trees also moving West?

FEI: Well, this is a very fascinating phenomenon. When we first looked at it, we have the exact same question that you do: Why the trees are moving westward? So, for climate change it means two things, often we think about temperatures warming up, but on the other aspect is that climate change is also causing precipitation pattern changes. In our study area in the Southeastern US like in Georgia, in the Carolinas and part of Florida even, they have a significant drought. On the other hand in the western portion of the study area -- primarily we’re talking about the Mid-western areas such as Missouri, Illinois -- they have more water or precipitation overall compared to historically what they have. So, the main driving factor that we are seeing that trees move Westward is due to the responding to the changing of moisture availability.

A Pennsylvania forest dominated by mixed broad-leafed trees. (Photo: Nicholas A. Tonelli, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, the way that the trees move, of course, is that trees don't pick up and walk on their roots. Their seeds go in one direction or another, and the saplings have more success then in a particular direction or another.

FEI: Yes, so we are not only talking about addition of the new seedlings, but we are also talking about mortality that is also happening for the big trees, especially given the drought that we have in the Southeast. And so, you think about this as an example, say, a line of people lining from Indianapolis to Atlanta. Every individual in that line has not moved in a single inch, but there are more people joining the line, say in Indianapolis or in Lexington, and there are people dropping out of the line in Atlanta, and then what's going to happen is the center of this line seems to have shifted.

CURWOOD: What kinds of trees are experiencing these shifts?

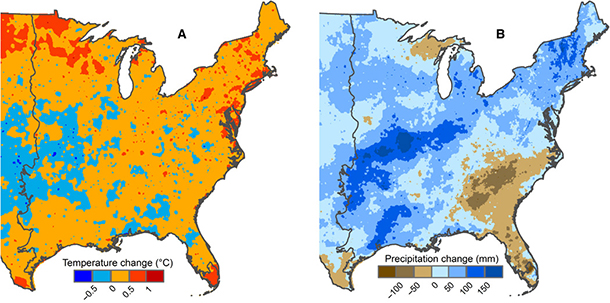

This figure from Songlin Fei’s paper shows changes in temperature, left, and precipitation, right, across the eastern United States, between the recent past (1951–1980) and the study period (1981–2014).

(Photo: Songlin Fei)

FEI: Well, so if we look at the groups that belong to certain families, what we find is that trees which are those flowering plants, broad-leafed plants, they are moving westward, so those are the oaks, maples, or the hickory species. But if you're looking at the specifically evergreen tree group which are the pines and spruce and firs, majority of these evergreen trees are moving northward.

CURWOOD: So, what's the difference then between the pines and plants like them versus the broadleaf trees like the oaks and maples that causes this difference in movement? I gather one is more sensitive to water and moisture. Which one would that be?

FEI: Well, so in our analysis, we followed up by looking at the traits of the individual species. We looked at over a dozen of traits, and for those westward moving trees in general they are more tolerant to drought. They also have some unique ability in terms of the seeds.

CURWOOD: So, why did the broadleaf trees, the oaks and the maples, if they have more drought tolerance, why are they moving west? It seems that there is more water to the west?

FEI: OK, well so we need to put into context even though we say there is more drought in southeast and getting wetter in the Midwest, in reality Georgia and Florida they still get way more precipitation than in say, Missouri or Illinois. But compared to the historic average, they are starting to get more moisture and these other trees are able to take the advantages of more moisture availability in a relatively dry area.

Forests in the Eastern U.S. are typically made up of diverse tree species, including both evergreen and deciduous trees. But the unnaturally rapid pace of tree species heading north and west could fragment these unique communities. (Photo: Nicholas A. Tonelli, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, in other words, they can pioneer to places that were previously too dry for them but now with just a little more moisture, they can go there. So, to what extent have tree species shifted their range in the past?

FEI: Trees are shifting its range all the time because of glaciation, or retreat of the glacier, and so there are studies in the New England area looking at how trees are tracing the changing temperature in the precipation in the last several thousand years. But the differences among our study and what we're seeing is that we are talking about a 30-year period, that we track trees shift between 1980 to 2015, and are seeing a big change that if only nature taking its course might take several thousand years that is happening.

CURWOOD: And how far over these three decades do these trees move? How far can they go?

FEI: So, on average, these trees have shifted about 15 kilometers per decade, so it's roughly about 10 miles per decade, close to 50 kilometers during the study period.

CURWOOD: Songlin, if the maples, if the oaks, if the hickory are moving to the west, and yet the pines and the spruce and the firs and moving to the north this will change the whole ecological balance in a forest system. How are forest ecosystems coping with this divergent change?

Songlin Fei is an Associate Professor in the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources at Purdue University. (Photo: Purdue University)

FEI: Yes, this is really a great question, and we don't really know yet because the current study we are looking at individual trees, but when we look at a forest this is really a composition of multiple species which in ecological terms we call a community. And so, we don't know whether the community is currently vulnerable for break down because of the different direction of this shift by individual species. So, we are interesting in looking at how these communities are responding as a group. Are there certain community groups that are more vulnerable than the others? And so, this is really what we are interested to look at next.

CURWOOD: Songlin Fei is an Associate Professor in the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources at Purdue University. Thanks, Professor, for taking the time with us.

FEI: Well, thank you, it's nice to be on the program.

Links

Science Magazine: ScienceAdvances: “Divergence of species responses to climate change”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth