May 26, 2017

Air Date: May 26, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Undue Corporate Influence on UN Climate Rules?

View the page for this story

The 2017 Climate session in Bonn, Germany was part of a series of sessions to develop the detailed rules of meeting commitments made under the Paris Agreement. Alleged undue influence of industry lobbying groups was one of the hottest topics. Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood discusses the controversy with Jesse Bragg, the Media Director for Corporate Accountability International. (09:35)

A Corporate Way to Meet the Paris Climate Goals

View the page for this story

Al Gore, Lord Stern and the head of Shell Oil are part of the ‘Energy Transitions Commission’ that has issued a report out how countries could halve global carbon emissions by 2040 and stay well below the 2 degree warming mark agreed at the Paris Climate Conference. Rachel Kyte, the UN’s Special Representative for Sustainable Energy was also part of the group and explained to Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer how we can create the necessary energy transformation. (07:12)

Emerging Science Note: Brazilian Peppertree

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

The Brazilian Pepper Tree is considered an invasive nuisance in the American South, but Emory University researchers have isolated a compound from the tree’s berries that appears to fight the superbug MRSA, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman reports that the extract seems to suppress the dangerous bacterium’s ability to secrete toxins. (01:30)

Trees On the Move

View the page for this story

The big old oak in your backyard might be solidly planted in place, but its acorns can travel. New research finds that, as the planet warms, seeds of many tree species in the Eastern U.S. are migrating, with pines and spruce heading north while oaks and maples are heading west of their historical ranges. Climate disruption with changes in temperature and precipitation are major causes, Professor Songlin Fei of Purdue University tells host Steve Curwood this rapid shifting of species ranges could change forest communities. (07:20)

The Early Bird Breeds Fast

/ Kara HolsoppleView the page for this story

The early bird, the proverb says, catches the worm. But new research from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History suggests that for many migrating birds in Western Pennsylvania, the changing climate means that they are arriving and breeding earlier so they don’t miss the insects their nestlings need. And as the Allegheny Front’s Kara Holsopple reports, some birds are adapting well and thriving while others are producing fewer chicks. (04:10)

Baby Tern Goes Exploring

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

On Falkner Island off the coast of Connecticut, new common and roseate tern parents can raise their offspring in peace, thanks to the protection of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. But as Living on Earth’s Resident Explorer Mark Seth Lender describes, one adventurous baby tern gives his anxious parents a fright as he sets out to dip his little feet into the ocean. (02:20)

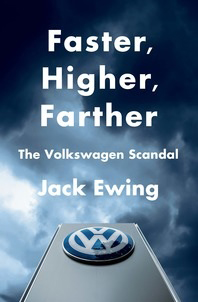

The VW Pollution Scandal

View the page for this story

In the mid-2000s, Volkswagen unveiled fuel-efficient diesel cars in the US that promised a future of affordable eco-friendly vehicles designed by one of the world’s biggest automakers. But in 2014, investigators found that the company was intentionally fooling EPA emissions testing and its cars actually pumped dangerous nitrogen oxides into the air. New York Times economics and business reporter Jack Ewing dissects the scandal and the VW corporate culture in the new book, Faster Higher Farther: The Volkswagen Scandal. He joins Steve Curwood to discuss the deception and the company’s future. (14:05)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jesse Bragg, Rachel Kyte, Songlin Fei, Jack Ewing

REPORTERS: Kara Holsopple, Don Lyman, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. At the recent UN climate negotiations in Bonn, corporate accountability watchdogs say multi-national fossil fuel companies had too much access and influence.

BRAGG: ExxonMobil, Shell, BP ... many of the actors that have been at the center of the climate crisis and funding denial, they have a role but we also need to limit their influence and understand that they shouldn't be writing the policy by which they need to abide.

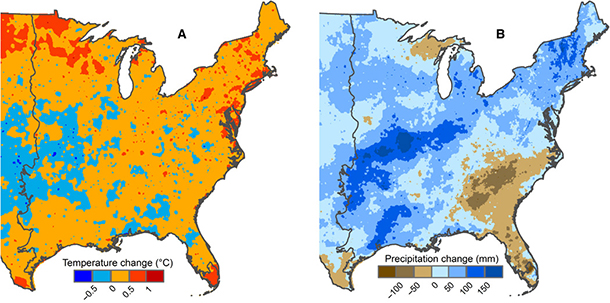

CURWOOD: Also, as temperature and rainfall patterns change with global warming, trees in the eastern U.S. are migrating to the wetter west and milder north.

FEI: These trees have shifted close to 50 kilometers during a 30-year period. And we are seeing a big change that only nature taking its course might take several thousand years.

CURWOOD: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Undue Corporate Influence on UN Climate Rules?

Technical experts discuss climate adaptation at Bonn 2017. (Photo: UNclimatechange, Flickr CC BY-NC-NA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The latest round of UN climate talks recently took place in Bonn, Germany, to hammer out some of the granular details of implementing the Paris Agreement. Among the many topics considered was whether corporations are having undue influence on international climate negotiations. The watchdog group, Corporate Accountability International, has been monitoring this issue, and one of their spokespeople, Jesse Bragg, joins us now. Welcome to the program, Jesse.

BRAGG: Thanks so much for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: Jesse, you were at this recent session in Bonn. How would you characterize the general mood of the negotiations?

BRAGG: Well, I think the uncertainty coming from the US definitely affected the mood. I think initially it affected things in a sort of level of uncertainty around the negotiations in general, but more and more what we're seeing is that countries are ready to move on without the US. Either way, whether the US decides to stay in this agreement or get out of this agreement, there's still going to be part of this agreement for the next four years. Those are the rules. Parties know from what the Trump administration had announced over the last few months that they have the coal industry and the US fossil fuel industry as one of their primary concerns. Parties are now looking at that and saying, ‘You know, stay or go, we need to move this forward without the US and without waiting on the US to get on board.’

CURWOOD: So give us your perspective here -- what do you think is going with corporate lobbying at these UN meetings?

BRAGG: Well, fundamentally, for about 22 years now, there have been no restrictions on trade associations and others representing the interest of corporations at these talks. And that becomes very problematic, especially when you look at some of the corporations these groups are representing – ExxonMobil, Shell, BP – and many of the actors that have been at the center of the climate crisis in funding denial, junk science, and other items that have slowed down the process on climate policy at home and abroad.

UNFCCC Executive Secretary Patricia Espinosa (left) and representatives of Fiji, Germany and the City of Bonn at the Bonn 2017 Conference. (Photo: UNclimatechange, Flickr CC BY-NC-NA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, you're not telling me that all corporate lobbying at these events is designed to subvert the process, are you?

BRAGG: What I'm telling you is that there’s actually ... it would be very to difficult to discern who is and who isn't in the interest of climate policy, and frankly, that's not the role of an intergovernmental process to pick the winners and losers in the private sector. And so we need to be very careful about who is at the table and who isn't at the table and especially not rely on PR and advertisements from the likes of the fossil fuel industry to try to convince us that they have the interests of people and the planet in mind when their actions over the last two decades, at least, have proved otherwise.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, the trade groups, of course, and other interest groups don't actually have a seat at the table. How are they able to court the diplomats and otherwise influence talks?

BRAGG: Well, you look at the example from COP 21. There were numerous examples of side events sponsored by the fossil fuel industry, by energy utilities where they wined and dined delegates and others, decision-makers, presumably toward their agenda. If you look at COP 19 in Warsaw, there was an entire parallel meeting hosted by the World Coal Association where delegates were invited, the head of the Secretariat of the Treaty actually spoke at that event.

CURWOOD: Which countries are championing limitations on corporate influence at the climate talks, and which made some kind of case for maintaining the kind of presence that companies have right now?

BRAGG: The champions of this issue were clearly Ecuador, and actually Uganda. Ecuador spoke representing the like-minded developing countries. Uganda spoke representing the least developed countries block. And actually, Senegal spoke representing the African negotiating group. Altogether, those groups represent far more than 70 percent of the world's population. And so, they were the leaders, but they were supported by Cuba. China spoke very, very strongly in support of these limitations, saying that the voices of the vulnerable are often drowned out by the voices of the rich and wealthy corporate interests. And those who were opposed to this were pretty easy to identify. You're looking at the US, Australia, Russia, and to some extent, the European Union, all places where the fossil fuel industry is based and representing countries that have the most at stake economically with the continuation of business as usual when it comes to extracting and burning fossil fuels.

CURWOOD: Jesse, talk to me about how these discussions in some ways parallel what happened at the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. This is back in 2003. What can we take away from how that treaty successfully put limitations on the tobacco industry's lobbying at those sessions?

Members of civil society gathered outside the UN meetings to challenge the corporate influence inside the talks.

(Photo: Corporate Accountability International)

BRAGG: It's a great example and a fantastic precedent to look to when you’re trying to figure out how to address industry influence in any policymaking process. When parties, governments, got together to hash out the framework convention on tobacco control, they quickly realized that one of the primary obstacles to their progress was the tobacco industry. You know, it's very easy to understand why the tobacco industry has no incentive to advance public health policy. Every step forward we take in public health and tobacco control means one less dollar in the pockets of tobacco industry. And so, they brought forward a really bold proposal, it was one line of text initially that just said that parties need to take steps to reduce the influence of the tobacco industry over public health. And since then, the implementation of this treaty has taken off. And that's really the model we need to look at when we're talking about the fossil fuel industry and climate change. We need information from them. They have a role. But we also need to limit their influence and understand that they shouldn't be writing the policy by which they need to abide.

CURWOOD: What corporate associations are exercising the most undue influence on the climate talks in your opinion?

BRAGG: The two organizations that really stood out in terms of influence over these recent talks were the International Chamber of Commerce and the US Chamber of Commerce. The International Chamber of Commerce, their role is really to keep the door open for businesses around the world. They believe, and they're very proud of it, that corporations, including the fossil fuel industry, need to be at the table helping parties write the rules that we're going to implement the Paris Agreement under, and so in that way they take every opportunity to advance and expand the access of the private sector. The US chamber actually held a side event at the UNFCCC talks in which they said that US fossil fuel corporations are going to be central to this process as well. One of their representatives actually then went on to say that the US is going to need to revise down its commitments to the Paris agreement, and more or less said that, people need to get used to that, that that’s the way it was, really towing the line of the Trump administration that these commitments need to be reviewed.

CURWOOD: Now, under the Paris agreement, the fossil fuel industry will be selling their products perhaps as late as 2050. It will take a while to phase out what they do. If they are, in fact, going to be part of the energy mix going forward as they are right now, why shouldn't they have some input into these negotiation processes so that they can deal with their business in an orderly fashion?

BRAGG: I think there's a big difference between having input and being part of a process, and what governments have been saying and what the sort of broad campaign around this is calling for, is to draw that line. When are we gathering input from those industries we're seeking to regulate and when are we actually allowing them to be part of the policymaking process? And so, certainly there's going to be a great need to consult with the industry and gather information from the industry as needed as we’re developing the implementation of this agreement, but the question here is not whether or not we need input. It's whether or not they should have a role in writing the rules, and that's what this discussion was about.

Jesse Bragg is the Media Director for Corporate Accountability International.

(Photo: Corporate Accountability International)

CURWOOD: When can we expect some sort of formal limitations to be agreed upon in terms of corporate lobbying at the UN climate meetings, if ever?

BRAGG: Well, it's a long process. Decisions are made by consensus at the UNFCCC, which means you need more or less the vast majority, if not all governments to agree, and so while that is a great process because it's inclusive, it does mean that things take time. We know the next milestone for this movement is next meeting in Bonn in May next year, so 2018, where parties will refer to submissions that governments and civil society groups have made on this issue and chart a path forward.

CURWOOD: Jesse Bragg is the Media Director of Corporate Accountability International. Jesse, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

BRAGG: Absolutely. Thanks so much for having me, Steve.

Related links:

- Corporate Accountability International

- CAI Report: Big polluters have backdoor access to UNFCCC

- Bonn 2017 UNFCCC website

[MUSIC: John Barry and His Orchestra, “Theme From Goldfinger,” live at the Royal Albert Hall, Bricusse/Newley/Barry, also available on EMI Records]

CURWOOD: Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line anytime at 800-218-9988, that's 800-218-9988. Our email address is comments@LOE.org. That's comments@LOE.org, and visit our webpage at LOE.org. That's LOE.org.

Coming up ... how trees move in response to global warming. It’s not always toward the poles. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: John Barry and His Orchestra, “Theme From Goldfinger,” live at the Royal Albert Hall, Bricusse/Newley/Barry, also available on EMI Records]

A Corporate Way to Meet the Paris Climate Goals

The report calls for a rapid transition to low-carbon technologies like Wind Power.

(Photo: Global Landscapes Forum, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. While some criticize corporate input at the UN global warming negotiations, others say it’s vital. For example, a team of investors, government, and climate advocates has developed an ambitious game plan to cut global carbon emissions in half by 2040. The group is called the Energy Transitions Commission and as well as the chairman of Shell Oil, it includes former US Vice President Al Gore, British economist Nicholas Stern and former US Senator and UN Foundation chief, Tim Wirth. Its new report is titled, “Better Energy, Greater Prosperity” and one of the report’s commissioners, Rachel Kyte, joins us now. She’s the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Sustainable Energy, and she spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

KYTE: The report basically says that there is a pathway to be being well below two degrees by the middle of the century and it depends upon on clean electrification. So, it means if we can clean up the electricity supply, if we can have massive inroads in energy efficiency, so the amounts of energy that we used to do thing, and if we electrify everything including particularly transport, then we can get to an energy system which allows to be well below two degrees, which allows us to be decarbonized by the middle of the century, and that that is affordable and feasible technologically. So, it's important because this group of people are saying this is doable. So, it's not an impossible task because of technology, because we believe that the costs of financing this are possible, and it's going to require enormous amounts of political will and real leadership, but it's possible.

PALMER: What are the financial obstacles that stand in the way of us getting to where we need to be?

KYTE: Well, actually, what is interesting about the work is that often we talk about the substantial amounts of investment in infrastructure that are needed, but actually when we went into this as a Commission and when we started looking at well, what's the incremental costs of doing this in such a way so we can have a pathway to clean electrification, and we have a pathway to an energy system which is the decarbonized and which is serving people efficiently, really, we're talking about one between $3 and $600 billion per annum over business as usual. So, I think that's the number we have to focus on. That's not a order of magnitude number that is unrealizable.

Meenakshi Dewan tends to maintenance work on the solar street lighting in her village of Tinginaput, India. (Photo: Abbie Trayler-Smith / Panos Pictures / Department for International Development, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

PALMER: So, it's not exactly pocket change, but it's not break the bank either.

KYTE: Yeah, I mean it's a third of a nuclear submarine, it's not something that we can't imagine.

PALMER: So, what kind of carbon pricing mechanisms will need to be put in place to make this happen?

KYTE: Well, I think the most important thing is that there is a price on carbon and the Commissioners are not prescriptive about which way to price carbon, but I think we all realize the price has to be an effective price, i.e. the price has to be sufficient to drive down the amounts of carbon in the energy system and the economy, and I think one of the problems we see around the world at the moment is that for many parts of the world, the price on carbon is too low to be effective, but so an effective price on carbon and then also an effective use of public policy to not subsidize fossil fuels where in fact that's harmful.

PALMER: What other public policies do you think need to be put in place?

KYTE: There is a need to sort of level the playing field for renewable energy in many parts of the world, and by that, what we mean is that the institutions and the systems and the regulation of the energy system in most countries was designed around a model of a centralized fossil-fuel-fed grid that took fossil feels and distributed that transmitted as far as it could be. I think what this report shows is that the energy systems of the future, in addition to being the carbonized, are going to be increasingly decentralized, so that they'll be much more distributed. There’ll be multiple grids, there’ll be electricity generated off the grid. Buildings will generate energy and store it and feed it back into the grid, so it's going to be a much more modular distributed system, and the institutions and the utilities and the regulations around that are going to have to shift, and so there's a really important role for public policy in embracing what energy systems of the future are going to look like and creating a level playing field for renewables to feed into the grid, to encourage more renewables, to encourage more distributed systems and I think that there's a lot of good work going on around the world and we see real process being made in many countries, but that's a big lift for government, and it’s a big lift for a new set of institutions, and I think that that comes out very strongly in the report.

PALMER: Yes, and particularly the situation of the developing world. Of course, in some instances they're a bit ahead of the curve because they don't have big centralized systems, so putting in a modular system would be easier. But still, having the cash to actually do it is a huge big hurdle.

Rachel Kyte is the Chief Executive Officer of Sustainable Energy for All and a member of the Energy Transitions Commission.

(Photo: World Bank Group)

KYTE: Yes, I think that for many developing countries they are facing a prior order of business, which is that they have large gaps in the access to energy. So you have energies where the penetration of electricity services is only perhaps 20, 25 percent of the population so the prior order of business is we've got to get everybody energy. The good news is that because of the falling price of technology, and because of innovations in business models as well, it's possible to imagine closing that energy access gap, perhaps more cheaply and quickly than had been the case in the past. So, closing the energy access gap remains very important, and also linked into that is the question of efficiency. We tend to think that efficiency is a question for developed countries, but there are very very energy-intensive economies that need to make more progress, but for many developing countries actually the level of energy intensity in their economies is very high where they're dependent on heavy fuel oil or diesel for the energy that they do generate, and so, for many developing countries as they imagine growth and urbanization, it's important they grow as efficiently as possible, that they really maximize their energy productivity.

PALMER: It is obviously an existential question, this future of the decarbonization of the planet. Are you actually hopeful?

KYTE: Well, I think that in my line of business it's better to be an optimist and wrong than to be a pessimist and right, and so yes, I am optimistic, but I'm also optimistic because I travel around the world and I talk to government, I talk to mayors, I talk to leaders of private companies and I talk to bankers and financiers. You know they, from a risk perspective, but also from the perspective of opportunity and more inclusive and cleaner growth then the energy transitions fundamental and people want to be on the leading edge of that rather than on back edge of that, and that's true in Zambia and true in Chile and Morocco, and I've just come back from Tonga and the Pacific and it's true in the South Pacific. And I think it's true in the cities and states in the United States of America, so yes, I'm an optimist that we can do this and I'm optimistic that we will do it. Where I think we really have to double down is with the speed with which we do it.

CURWOOD: That’s Rachel Kyte, CEO of Sustainable Energy for All. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Related links:

- Better Energy, Greater Prosperity Flagship Report

- About Rachel Kyte

- LOE spoke with Rachel Kyte just prior to the 2015 Paris climate conference

[MUSIC: Renaissonics, “E la don, don Verges Maria” on Carols for Dancing, Mateo Flecha? (1556), WGBH Educational Foundation recording]

Emerging Science Note: Brazilian Peppertree

The red berries of the Brazilian Peppertree. (Photo: Javier Alejandro, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: In a minute, trees that travel ... but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

LYMAN: The Brazilian peppertree is a weedy, invasive species native to South America. Although considered a nuisance in Florida, where it grows in dense thickets and crowds out native plants, scientists at Emory University say traditional healers in the Amazon have treated wounds and skin infections with its bark and berries for hundreds of years.

Now, the Emory researchers have isolated a compound from the berries that appears to prevent skin lesions in mice infected with MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a bacterium that can cause serious infections, and is resistant to penicillin and cephalosporin antibiotics.

The scientists say that the compound doesn’t kill the bacteria, but represses a gene that allows them to communicate. This essentially disarms the MRSA bacteria and prevents them from excreting toxins that damage tissues.

Antibiotic-resistant infections are a widespread and growing problem that cause about two million illnesses and 23,000 deaths in the United States each year. The researchers say the Brazilian pepper tree extract could not only provide new ways to treat and prevent these infections, but do so without boosting the bacteria’s ability to resist our antibiotics. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Related links:

- Press release: “Brazilian peppertree packs power to knock out antibiotic resistance”

- Nature article in Scientific Reports: “Virulence Inhibitors from Brazilian Peppertree Block Quorum Sensing and Abate Dermonecrosis in Skin Infection Models”

- National Invasive Species Information Center: The Brazilian Peppertree

[MUSIC: London Symphony Orchestra, “March of the Ents” on Lord of The Rings, The Complete Recordings , composed by Howard Shore, Reprise Records]

Trees On the Move

White pine forest in Pennsylvania. Conifer species including the white pine, Pinus strobus, tend to be moving north as the Eastern U.S. warms. (Photo: Nicholas A. Tonelli, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Yes, we have another tale of trees, trees that are moving, though not as dramatically as the Ents in the Lord of the Rings epic. And not individual trees of course, but species that are migrating. A newly-published study confirms that 86 tree species of the Eastern U.S. are moving as the planet warms. But not just north: some are heading west. Songlin Fei of Purdue University is the lead author of the new study and joins me now. Professor Fei, welcome to Living on Earth.

FEI: Well, thank you, it’s very nice to be here.

CURWOOD: So, tell me what's going on here? The Northward shift is not so surprising, since that's mostly having to do with temperature and climate change certainly is warming things up, but why are trees also moving West?

FEI: Well, this is a very fascinating phenomenon. When we first looked at it, we have the exact same question that you do: Why the trees are moving westward? So, for climate change it means two things, often we think about temperatures warming up, but on the other aspect is that climate change is also causing precipitation pattern changes. In our study area in the Southeastern US like in Georgia, in the Carolinas and part of Florida even, they have a significant drought. On the other hand in the western portion of the study area -- primarily we’re talking about the Mid-western areas such as Missouri, Illinois -- they have more water or precipitation overall compared to historically what they have. So, the main driving factor that we are seeing that trees move Westward is due to the responding to the changing of moisture availability.

A Pennsylvania forest dominated by mixed broad-leafed trees. (Photo: Nicholas A. Tonelli, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, the way that the trees move, of course, is that trees don't pick up and walk on their roots. Their seeds go in one direction or another, and the saplings have more success then in a particular direction or another.

FEI: Yes, so we are not only talking about addition of the new seedlings, but we are also talking about mortality that is also happening for the big trees, especially given the drought that we have in the Southeast. And so, you think about this as an example, say, a line of people lining from Indianapolis to Atlanta. Every individual in that line has not moved in a single inch, but there are more people joining the line, say in Indianapolis or in Lexington, and there are people dropping out of the line in Atlanta, and then what's going to happen is the center of this line seems to have shifted.

CURWOOD: What kinds of trees are experiencing these shifts?

This figure from Songlin Fei’s paper shows changes in temperature, left, and precipitation, right, across the eastern United States, between the recent past (1951–1980) and the study period (1981–2014).

(Photo: Songlin Fei)

FEI: Well, so if we look at the groups that belong to certain families, what we find is that trees which are those flowering plants, broad-leafed plants, they are moving westward, so those are the oaks, maples, or the hickory species. But if you're looking at the specifically evergreen tree group which are the pines and spruce and firs, majority of these evergreen trees are moving northward.

CURWOOD: So, what's the difference then between the pines and plants like them versus the broadleaf trees like the oaks and maples that causes this difference in movement? I gather one is more sensitive to water and moisture. Which one would that be?

FEI: Well, so in our analysis, we followed up by looking at the traits of the individual species. We looked at over a dozen of traits, and for those westward moving trees in general they are more tolerant to drought. They also have some unique ability in terms of the seeds.

CURWOOD: So, why did the broadleaf trees, the oaks and the maples, if they have more drought tolerance, why are they moving west? It seems that there is more water to the west?

FEI: OK, well so we need to put into context even though we say there is more drought in southeast and getting wetter in the Midwest, in reality Georgia and Florida they still get way more precipitation than in say, Missouri or Illinois. But compared to the historic average, they are starting to get more moisture and these other trees are able to take the advantages of more moisture availability in a relatively dry area.

Forests in the Eastern U.S. are typically made up of diverse tree species, including both evergreen and deciduous trees. But the unnaturally rapid pace of tree species heading north and west could fragment these unique communities. (Photo: Nicholas A. Tonelli, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, in other words, they can pioneer to places that were previously too dry for them but now with just a little more moisture, they can go there. So, to what extent have tree species shifted their range in the past?

FEI: Trees are shifting its range all the time because of glaciation, or retreat of the glacier, and so there are studies in the New England area looking at how trees are tracing the changing temperature in the precipation in the last several thousand years. But the differences among our study and what we're seeing is that we are talking about a 30-year period, that we track trees shift between 1980 to 2015, and are seeing a big change that if only nature taking its course might take several thousand years that is happening.

CURWOOD: And how far over these three decades do these trees move? How far can they go?

FEI: So, on average, these trees have shifted about 15 kilometers per decade, so it's roughly about 10 miles per decade, close to 50 kilometers during the study period.

CURWOOD: Songlin, if the maples, if the oaks, if the hickory are moving to the west, and yet the pines and the spruce and the firs and moving to the north this will change the whole ecological balance in a forest system. How are forest ecosystems coping with this divergent change?

Songlin Fei is an Associate Professor in the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources at Purdue University. (Photo: Purdue University)

FEI: Yes, this is really a great question, and we don't really know yet because the current study we are looking at individual trees, but when we look at a forest this is really a composition of multiple species which in ecological terms we call a community. And so, we don't know whether the community is currently vulnerable for break down because of the different direction of this shift by individual species. So, we are interesting in looking at how these communities are responding as a group. Are there certain community groups that are more vulnerable than the others? And so, this is really what we are interested to look at next.

CURWOOD: Songlin Fei is an Associate Professor in the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources at Purdue University. Thanks, Professor, for taking the time with us.

FEI: Well, thank you, it's nice to be on the program.

Related links:

- Science Magazine: ScienceAdvances: “Divergence of species responses to climate change”

- Nature: “Trees in eastern US head west as climate changes”

- About Songlin Fei’s research

[MUSIC: London Symphony Orchestra, “March of the Ents” on Lord of The Rings, The Complete Recordings, composed by Howard Shore, Reprise Records]

The Early Bird Breeds Fast

Avian research coordinator, Luke Degroote, examines a Northern Flicker at the Powdermill Nature Reserve. The Flicker and other local birds have been breeding earlier in the year and producing fewer chicks.

(Photo: The Allegheny Front)

CURWOOD: Our changing climate is affecting many species, and migrating birds are especially sensitive. As seasons shift they may get out of step with the food sources birds rely on to nest and raise their babies. So as the Allegheny Front’s Kara Holsopple reports, new studies show that for some early birds to catch the worm, they have to breed sooner in the spring.

HOLSOPPLE: Luke DeGroote is the avian research coordinator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. And he runs the bird banding program at their Powdermill Nature Reserve in Westmoreland County. Right now he’s in the thick of spring migration.

DEGROOTE: It’s sort of a bit like fishing, in a way. We put our nets to see what we catch.

HOLSOPPLE: From early in the morning, until about noon, he and a handful of volunteers patrol a series of nets - kind of like volleyball nets -- that are set up around the property.

DEGROOTE: This is a red-winged blackbird ... I’m going to grab him by the body, and very carefully pull the netting off the tip of the wing.

HOLSOPPLE: Birds like this little guy, with the distinctive red patch on its wing, get caught up in the fine netting, and drop down into a pocket where they’re scooped up by researchers.

DEGROOTE: The red-winged blackbirds tend to hold on tight.

HOLSOPPLE: He’s really clinging on. When it’s finally freed, DeGroote gingerly places the bird into a bag, like a small pillow case, and loops its string to a red carabiner around his neck … Red indicates which size metal band to place on the blackbird’s leg -- so it can be tracked.

DEGROOTE: I’m heading to three -- if anyone wants to check the edge of the ponds that’d be great …

[BLEEPING SOUND]

Mammoth Lake in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania. Birds here have been breeding sooner in the spring in order to keep pace with earlier warmer temperatures. (Photo: Jon Dawson, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

HOLSOPPLE: All the birds they capture this morning -- and every morning -- are taken back to a small lab where they’re banded with a unique number and weighed. Researchers also examine their feathers to determine age, and if the birds are getting ready to breed.

DEGROOTE: The females -- when they’re in breeding condition -- will lose the feathers on the breast and then insert some fluid to create really, like, a hot water bottle for the eggs.

HOLSOPPLE: They’ve been collecting these data here at Powdermill, consistently, for over 50 years. That’s how they know -- from previous studies -- that birds are migrating here a little earlier in the spring than they used to, and breeding sooner. And that got DeGroote and his research partner Molly McDermott thinking.

DEGROOTE: All right if they're migrating early and breeding early, are they breeding earlier because they're migrating early or are they breeding more quickly after they arrive?

HOLSOPPLE: So what did you find?

DEGROOTE: They're basically getting busier earlier after arrival.

HOLSOPPLE: That’s true for the majority of the 17 common bird species they studied. In their recent paper, published in the journal Plos One, they connect early breeding to warmer springs and climate change. Because while birds are arriving here day earlier for every one degree Celsius that the temperature has warmed over the last few decades, spring buds are opening three days earlier. Those plants and the insects birds rely on for food, for the survival of their young, are now sort of mismatched with the timing of spring migration. So these birds are responding the only way they can.

DEGROOTE: They're having to catch up because they're not able to catch up during migration -- they're not able to sort of advance that as much as the plants -- they have to begin breeding soon after arrival if they want to breed at a time period that's sort of what they're used to.

A meadow blooms in Lehigh, PA. Researcher Luke Degroote says while birds arrive a day earlier for every one degree Celsius the temperature has warmed over recent decades, spring buds are opening three days earlier. (Photo: Nicholas A. Tonelli, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

HOLSOPPLE: When the tender plants and insects they eat are at their peak. A quarter of the species which bred earlier in this study -- like black-capped chickadees -- had more babies in these warmer years. But another 25 percent -- including hooded warblers -- didn’t. Their productivity declined.

DeGroote says you can look at the results of this study two ways. On the glass-half-full side, it shows some bird species are flexible, and capable of adapting to climate change. But while weather isn’t climate -- a few years ago there was a hard winter and later spring, this year is warmer -- he says the overall trend for birds is worrying.

DEGROOTE: If it continues to warm that window which they have to be adaptable is shrinking.

HOLSOPPLE: This most recent study just looks at the timing of bird breeding, but DeGroote says it’s easy to see implications for the ecosystem. If some species are less successful because of climate change, there might be fewer birds to pick off insects or spread seeds from the fruits they eat.

I’m Kara Holsopple.

CURWOOD: Kara Holsopple reports for the Pensylvania public radio program, the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Allegheny Front story

- Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Powdermill Nature Reserve

[MUSIC: Hubert Laws, “Fire and Rain” on Afro-Classic, composed by James Taylor, CTI Records]

Baby Tern Goes Exploring

A fluffy tern chick goes exploring at the water’s edge. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: We head to the seashore now with our explorer in residence, Mark Seth Lender. In his own backyard off the Connecticut shore lies Falkner Island, only four-and-a-half acres in size, but with an outsized importance as one of largest roseate and common tern colonies in the East. The US Fish and Wildlife Service goes to great lengths to protect the terns, keeping people, their pets, and invasive predators away -- but did take Mark and his camera for a visit. And there he found the anxieties of parenting can be common to -- well, many species.

Baby Has New Shoes

Common Tern, Falkner Island © 2016 Mark Seth Lender All Rights Reserved

A flustered tern parent appears to chide its offspring. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

LENDER: Like baby in his baby shoes, Tern is going for a walk. The way some kids do without holding onto a hand, without looking back.

But there are no shoes! His little feet are webbed like his Mom and Pops (bright orange-red and not quite steady as he walks). He is heading out all by himself. And does not pause and will not stop. The stubs that will be wings wheel and shy like little arms. He hops, over the flotsam of green seaweed. He drops, into the jangle of dried reeds, and crosses the tideline. All dandelion fluff round as a puffball soft as fleece, small enough to fit in the pocket of your blouse -- there he goes! Along the reach of rustling pebbles and slipper shells, off to dip his new toes in the little waves that wash up on the beach.

Tern egg among dried seaweed and stones. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Meanwhile, Mom and Pops don’t like any of this. They leave the nest and close upon his unsteady heels, flapping and whistling and calling him back, “Wait up, kid, you’re gonna hurt yourself! You’re not ship-shape, your tail’s out of trim. You can’t get out if you fall in!”

Mom lands on a rock that towers over him.

Pop cries out from the shore: “Whatcha thinkya doin out there!”

Threats and entreaties Kid Tern ignores as he touches, and tastes, where the ocean gently roars. We’ve all been there. That time of life. We knew better than anyone; anyone put there to tell us no. Our yes was so much stronger than that. We were sure, we had no fear.

[SOUNDS OF TERNS CALLING]

An adult tern flies off with a fish. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Mark Seth Lender recorded these terns at Falkner Island, and for pictures, wing on over to our website, LOE.org.

[SOUNDS OF TERNS CALLING]

Related links:

- To learn more about Falkner Island and the work of the USFWS, visit Mark’s website

- USFWS Stewart B. McKinney Wildlife Reserve

[MUSIC: Hubert Laws, “Moonlight Sonata” on My Time Will Come, composed by Beethoven/arr.Laws, MusicMasters Jazz]

CURWOOD: Coming up ... the scandal that has run over the “people’s car.” That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies -- combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Hubert Laws, “Moonlight Sonata” on My Time Will Come, composed by Beethoven/arr.Laws, MusicMasters Jazz]

The VW Pollution Scandal

Volkswagen’s supposedly “clean diesel” vehicles in 2013. (Photo: John Biehler, Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. In 2016, Volkswagen became the world’s largest auto company, edging out Toyota, but VW’s outlook has been badly dinged by a scandal involving fraudulent testing of pollution levels from its popular diesel cars. VW became famous for the Beetle back in the 1960s and 70s, and built on that reputation for moderately priced and reliable cars, including the Golf, and Passat. In recent decades, the company introduced fuel-efficient, and supposedly environmentally-friendly diesel cars to the US market -- and won a substantial market share. But in 2014, investigators found that the low emissions ratings were based on fooling the testing sensors, while in reality the cars belched high levels of toxic nitrogen oxides. New York Times economics and business reporter Jack Ewing explores the scandal in his new book "Faster, Higher, Farther". Welcome to Living on Earth, Jack.

EWING: Thanks for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, give us the background here. We know that VW has paid huge fines, I think, what, $20 billion for cheating on the pollution testing from diesel, but briefly what did they do?

EWING: Well, it started way back in 2007 and they wanted to start a new strategy in the US. They were trying to figure out a way to compete with the Toyota Prius, so they hit on the idea they would sell Americans on the idea of diesel engines in passenger cars.

CURWOOD: Right, because diesel is, what, 30 percent more efficient than gasoline typically, right?

EWING: Right, yeah, diesel is more fuel efficient but the big drawback is that it burns at a higher temperature, and therefore it produces a lot more nitrogen oxides which have a whole array of harmful effects. So, as the engineers are working on this motor, at a certain point they realize they could not meet these nitrogen oxide standards in the United States, which are stricter than those in Europe, so they decided to cheat. All engines these days are controlled by a computer under the hood, so there was software in this computer that could control the whole hundreds of thousands of engine functions, one of which is the way that the pollution control system worked, and getting all this to work together was really difficult. So, they realized they could make it work some of the time, but not all the time. They decided that some of the time would be when the emissions police, so to say, were looking, so the software could actually recognize the simulated driving cycle that the regulators used when they test a car for emissions. They put the car on rollers and they go at different speeds and this is publicly known and predictable, so it was possible to come up with software that could tell when the test was going on, and turn up the pollution controls so the car would pass, and then the rest of the time they didn't really need to worry about the pollution controls because they knew nobody was looking.

Production pushes ahead in factories at the Volkswagen headquarters in Wolfsburg, Germany. VW's populist origins are linked to Nazi dictator Adolph Hitler’s call in the late 1930s for a “people’s car.”

(Photo: Automotive Rythms, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, why not have the pollution controls? What was the problem with having a clean tailpipe coming out of these cars?

EWING: There's all sorts of pollutants coming out of a diesel car, and it's very hard to get them all in control at the same time, so the technology that helped lower the nitrogen oxide emissions created more particles which are also bad -- they cause cancer, the fine particles that get deep in your lungs. So, when they ran this technology full blast, it caused the particle filter to fail too quickly, and the filters are expensive. They didn't want customers to be reporting after 30,000 miles or whatever that their particle filter was busted. And so they were faced with this trade off of the particle filter, the nitrogen oxides, and they decided to spare the particle filter, they would find a way to cheat on the nitrogen oxides.

CURWOOD: Explain to me what it is that BMW and Mercedes did to meet the diesel emission standards in the US -- their process, I guess Mercedes calls it Blutech -- and why didn't VW choose to go that way?

EWING: Well, there's basically two kinds of emissions technology, one is a sort of catalytic converter that traps the nitrogen oxides, and the other one is something that uses a tank with the urea chemical and it's sort of sprays it into the exhaust and that neutralizes the nitrogen oxide, and that second technology with the urea, it's more effective, and actually when Volkswagon was first going to launch diesel in the US, they thought about using that but they were worried it would be more expensive -- it also requires more of customer because you have to keep filling up the tank with this chemical solution in it, and in fact Volkswagon did later use that technology but they didn't make the tank big enough. I think they were worried that it would be an inconvenience for users if every 6,000 miles they had to fill the tank up, plus it would rob space from the trunk, and that was less of a problem for Mercedes and BMW because those tend to be bigger cars.

Jack Ewing’s new book is titled, Faster, Higher, Farther: The Volkswagen Scandal.

(Photo: W.W. Norton & Company Publishers)

CURWOOD: So, they fooled emissions testers. How was this discovered? It's an interesting story you tell, I guess it involves some young folks from West Virginia, huh?

EWING: Yeah, it was a lot of happenstance, actually. You know, Volkswagen almost got away with it, but in 2013, they had a controversy in Europe about making nitrogen oxide standards stricter, and the carmakers over in Europe were saying, “No, that'll never work, we can’t do it, blah blah blah.” But at the same time, Volkswagen over in the United States was meeting the US standard supposedly. There's a nonprofit organization called International Council on Clean Transportation. This nonprofit organization said, “Well, how come they can do it over there and they're saying that they can't do it over here in Europe?” So, they hired West Virginia University which has an Auto Emissions Study program to test the cars on the road, and that's what was really novel about this is that they took them out on the street with this kind of Rube Goldberg type apparatus on the back that measured the emissions as it was coming out of the tailpipe, and they noticed that out on the road the Volkswagens polluted way more than they did in the lab -- 35, 40 times more. So, in 2014, they've published a study with their results but they still didn't realize exactly what found. They knew something was wrong but they figured it was a technical problem. Nobody really thought Volkswagen would be so brazen to cheat.

CURWOOD: And by the way Jack, at this point you write that the West Virginia group was also testing BMW diesels and they were coming up just fine.

EWING: Right they tested a BMW and basically the BMW equipment worked. BMWs are more expensive cars, they're bigger cars, there was more room for equipment and they had a type of technology which is better than what Volkswagen was using at that time. They published the study and the regulators in California, the California Air Resources Board happened to be at the conference where the study was presented, and say said, “Hmmmm, that doesn't sound good,” and then they started a much more detailed study, but it was another year and a half before in September 2015 when Volkswagen finally confessed.

The Volkswagen Beetle, of which this 1969 model was just one of many iterations, remains to this day the most popular car VW has ever sold. (Photo: Manoj Prasad, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, Jack, what does this say about the company and its ethics, and perhaps you could start by telling how VW was originally conceived by the Porsche family which founded this line of automakers.

EWING: Yeah, well it was actually the Nazis back in the 30s. They wanted to build what they call the people's car, a Volkswagen, that would make automotive transportation available to everybody. It is really a propaganda project because they never actually built that many. But Ferdinand Porshe designed what later became known as the Beetle, and then after the war it actually a British officer who got the factory going again producing the Beetles initially as a form of transportation for the British occupying army, and eventually that became the basis for Volkswagen as a car company.

CURWOOD: Ferdinand Piëch, the grandson of Ferdinand Porsche, worked his way up through the ranks of the VW organization, ultimately to take control as CEO in 1993. How was he was able to do that? How did he rise up the ranks and in what ways did he reshape how the company operated?

Ferdinand Piech, the grandson of Volkswagen Beetle creator Ferdinand Porsche, served as CEO of the company from 1993 until 2002, and chaired the Supervisory Board until 2015. Piech’s promotion of a top-down corporate culture at Volkswagen may have kept lower-level employees from challenging executive orders. (Photo: Audi AG, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

EWING: He really rose on his own merits. I suppose it didn't hurt being the grandson of Ferdinand Porsche, but he started at Audi as a junior executive and eventually rose to become the chief executive. At that time, it wasn't a luxury car maker, it wasn't known as one, and he was able to, with a number of interesting innovations and patients like four-wheel drive in passenger cars and diesel, for that matter, he made Audi into a premium luxury car maker to compete with BMW and Mercedes, and on the strength of that then he became chief executive of Volkswagen in 1993, but he also created, he is often blamed for creating a company culture that allowed the emission scandal to take place.

CURWOOD: What else might Ferdinand Piëch be accused or suspected of in terms of the less than stellar corporate culture of VW?

EWING: Well, he was known for being very dictatorial, very quick to fire people who didn't meet his expectations, setting very ambitious goals for people, goals that sometimes were regarded as next to impossible. And so, it was a culture where it was very difficult to say no to top management -- that was career death at Volkswagen. And so, a lot of people believe that that allowed the scandal to become what it was.

CURWOOD: Diesel fuel passenger cars really began with VW, I guess when Ferdinand Piëch lead this team successfully adapt the fuel from trucks. But how did diesel become such an interval part of the VW branding and how did that branding change depending on the market that VW diesel cars were being sold?

EWING: The biggest disadvantage of was, it's noisy and smelly, and with the combination of pollution control equipment and engine computers and fuel injection, they were able to civilize it, and the other very important thing was that they sold European politicians on the idea that this was good for the environment, so that most countries in Europe including Germany, diesel fuel has lower taxes so it's always about 10 cents cheaper at the pump than gasoline. That's different than United States where diesel is usually more expensive. So that is really the technology that helped Volkswagen to become the biggest carmaker in Europe by far with about a quarter of the market, which is double what anybody else has.

The Toyota Prius represented the biggest threat to Volkswagen’s diesel-fueled cars in the American market. In an effort to compete, Volkswagen fraudulently gamed emissions testing in the US.

(Photo: Automotive Rythms, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, what drove VW to embrace this image of environmentally friendly fuel-efficient vehicles in the US?

EWING: Well, they were desperately trying to get market share in the US. They were very strong in Europe. They were pretty strong in South America and China, but the US had really been a big problem for Volkswagen ever since the heyday of the Beetle. Even to this day, Volkswagen has never sold as many cars in the United States as they did in the late 1960s. So, they were trying get back that market share that they use to have. And so, they hit on the idea, “Well what's our unique selling point -- diesel -- and they thought they could position against the Toyota Prius and sell it to environmentally-conscious buyers because it has fuel economy, not quite as good as the Prius, but pretty close, and they were able to convince people that it was just as clean, and there was a lot of advertising behind this pitch, a lot of people who bought Volkswagens were people who were very environmentally conscious, and that's one of the things that's creating such problems for Volkswagen now, because their customer base was really quite angry when they found out they had been misled.

CURWOOD: So, at the end of the day what does the Volkswagen scandal around diesel mean for the future of diesel going forward here in the US, do you think?

EWING: I think diesel in the US … it's hard to see that it has much of a future. In Europe, you see already that the market share of diesel is going down because the carmakers realize they can't fudge things any more. They're going to have to improve the equipment. That's going to add to the cost and make it less attractive compared to gasoline, and I think the carmakers have also realized that long-term, they have to start making a shift to electric and that's the only way that they're going to meet the stricter emission rules.

Jack Ewing is a New York Times reporter covering business from Frankfurt, Germany. (Photo: Jack Ewing @JackEwingNYT-Twitter)

CURWOOD: What are the odds of VW reinventing itself and rescuing its reputation?

EWING: Well, they’re trying. They said they're shifting their strategy to focus on electric cars they're investing in as part of the settlement in the United States they’re building a charging grid, but it's going to be tough because there's a lot of new competitors in the market. Tesla, we don't know exactly what Google and Apple are going to do, but they are obviously interested in the car industry and they have actually much more financial resources than the car companies, and Volkswagen is handicapped because of all the money they've had to pay in fines and legal settlements as part of the emissions scandal. So it's going to be a tough transition. They're not as efficient as Toyota, and it's expensive to manufacture in Germany. They have a lot of issues that existed before and this is one other big thing on top of that and the scandal is not over, there are still developments, it's still a distraction for management. So, it's very tough situation for Volkswagen.

CURWOOD: Jack Ewing is a reporter for the New York Times covering business and economics from Germany. His new book is called, “Faster, Higher, Farther: The Volkswagen Scandal.” Thank you so much, Jack.

EWING: Steve, thanks a lot for having me. I really appreciate it.

Related links:

- Faster, Higher, Farther: The Volkswagen Scandal is published by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

- Reuters: “VW resumes U.S. diesel sales after emissions scandal”

- EPA: Volkswagen Light Duty Diesel Vehicle Violations for Model Years 2009-2016

- Jack Ewing writes for the NYTimes

[MUSIC: Simon Wynberg, “Mariah’s Watermill” on Guitar Works, Narada Lotus]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Alex Metzger, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. And we’re happy to welcome a new intern this week, Matt Hoisch. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org -- and like us, please, on our Facebook page -- PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth