Henry David Thoreau Turns 200

Air Date: Week of July 7, 2017

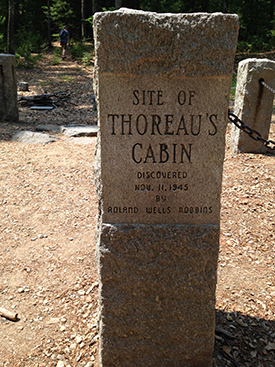

The site of Thoreau’s cabin in Walden Woods. On the left is a pile of stones left by Thoreau’s admirers, which grows year by year, and on the right are the granite blocks marking the cabin site. (Photo: Bill Illot, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Walden Pond, where Henry David Thoreau famously ‘lived deliberately’ in a small hand-built cabin is popular, and Thoreau walked, thought, and observed in the surrounding woods. To protect them from development, conservationists, Thoreau scholars and even a rock star founded the Walden Woods Project. 200 years after Thoreau’s birth, Walden Woods now helps students and teachers learn about Thoreau, his philosophy and nature itself. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering went to the woods to find out how and why Thoreau’s legacy lives on

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Henry David Thoreau was a great nature writer and thinker, and if he were still alive, he’d celebrate his two hundredth birthday on July 12th. Thoreau was not widely read in his lifetime, yet his book “Walden” has become an American classic, and his essay “Civil Disobedience” inspired non-violent leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi and the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. 200 years after Thoreau’s birth, his legacy lives on, not only in his complex prose, but also in the woods of Concord, Massachusetts around Walden Pond. He famously wrote about his two years living there in a simple hut, though he frequently went home to his mother to get his laundry done and for a home-cooked meal.

Conservationists, scholars, teachers, even a rock star have helped preserve the legacy of Thoreau and Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering went to the woods to find out how and why they’re keeping the sage of Walden alive.

Walden Pond turns into a pleasant swimming hole in summer – but it has historical significance, too. (Photo: Oleg., Flickr CC BY 2.0)

[SPLASHING, WATER LAPPING AT SHORE, LAUGHING, LIFEGUARDS, FOOTSTEPS IN SAND]

DOERING: In summer, Walden Pond is a cool and deep, blue-green oasis surrounded by broadleaf forest, the verdant trees in full leaf. A pleasant sandy beach curves along its eastern shore, where lifeguards watch over children and adults who venture in for a swim.

[CHILDREN PLAYING, SWIMMING SOUNDS]

DOERING: But this is no ordinary swimming hole. It’s just down the road from the town of Concord, where Henry David Thoreau and other transcendentalists like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, and Nathaniel Hawthorne developed their philosophy. In close proximity to these luminaries and as the location of the cabin where Thoreau “lived deliberately” for two years, Walden has been called the birthplace of the American conservation movement.

[CHILDREN PLAYING, SWIMMING SOUNDS]

DOERING: Yet it wasn’t a trackless, remote wilderness then, and, just a short drive from Boston, it’s now visited by nearly 700,000 people each year.

[SOUNDS OF WALKING]

Many walk the path that winds along its shore to the site of Thoreau’s cabin, the simple 10 by15 wood structure long gone, but its original location marked by granite blocks, and an impressive pile of stones left in tribute to the writer that grows, year by year.

Thoreau built his cabin near the shore of Walden Pond in 1845 from repurposed wood. When Thoreau left two years later and no longer needed the cabin, a local farmer took it apart and put the wood to use on his farm. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

But the pond and nearby cabin are just the tip of the iceberg, says Kathi Anderson, the Executive Director of the Walden Woods Project.

ANDERSON: Thoreau lived in the woods. And while his cabin was on the shores of Walden Pond, he spent most of his life walking around the woods of Walden Woods.

DOERING: Anderson’s nonprofit was founded in part to protect those woods, which have diminished over the years. A major highway now bisects Walden Woods, and the town of Concord’s old landfill sits where Thoreau used to roam. But the Walden Woods Project also exists to carry on Thoreau’s legacy of reconnecting people with the outdoors. Anderson says, today that’s needed more urgently than ever.

ANDERSON: There’s a disconnect between kids and nature. And we have to reconnect that.

[OUTDOOR CLASSROOM SOUND]

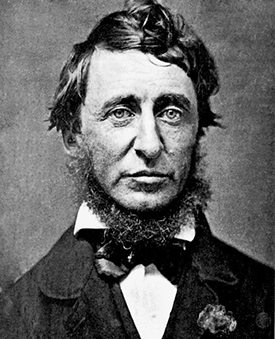

Daguerrotype of Henry David Thoreau in June 1856. (Photo: Benjamin D. Maxham, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

DOERING5 In the woods not far from the pond, I see the seeds of that reconnection being planted, with the help of several mason jars, full of brownish water.

BURNE: These jars that are on the table that are kind of murky. This is what we call pond glop.

[CROWD GIGGLES]

WOMAN: Is that a technical term?

[MORE LAUGHS]

BURNE: Yeah, it sure is.

DOERING: Ecologist Matt Burne and twenty or so adults sit in the shade in a clearing in the woods. They’re teachers, here to learn. One woman asks Burne what the curious little creature in her mason jar of pond scum is.

WOMAN: It’s like this little red squiggle.

BURNE: Oh the red squiggle. That’s a chironomid midge larvae. It’s a flying insect.

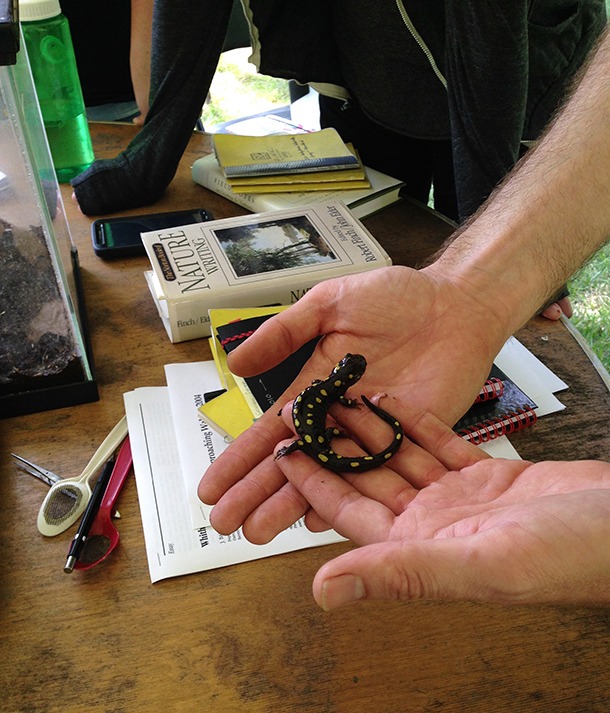

DOERING: They seem fascinated by the little creatures in their jars, and some others that Burne collected from the forest nearby: a wood frog, a water scorpion, a red-spotted newt, and a spotted salamander. They’re art teachers, science teachers, and even an elementary school librarian. The Walden Woods Project is schooling these teachers in how to bring their students outdoors – or, to bring the outdoors in -- using Thoreau as a guide. They even get to meet the man himself.

SMITH: I am living at the pond to meet life, be it good or be it bad.

DOERING: Richard Smith does a professional impression of Henry David Thoreau, and all of a sudden it’s a warm July day in 1847.

Matt Burne, the Conservation Director of the Walden Woods Project, instructs a class of teachers about how to bring the outdoors into their classrooms. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

SMITH: I felt that for too long, I was the observer of my life and not the participant.

DOERING: Smith sports a beard just around his chin, reminiscent of Thoreau’s style, and wears a tweed vest and trousers. He keeps a straight face as he channels Thoreau’s kind of dry humor.

SMITH: Have you seen Mr. Emerson’s house, over on the Cambridge Turnpike?

AUDIENCE: Yes, sir.

SMITH: I live in very dangerous prosperity when I am over there. [AUDIENCE LAUGHS]

DOERING: Enjoying plenty of solitude at Walden Pond gave Thoreau the space to reflect on the injustices in his society. One teacher asks him to tell them about the night he spent in jail, which he describes in his famous essay, “On the Duty of Civil Disobedience.”

SMITH: Oh, have you been to jail?

[AUDIENCE LAUGHS]

It is a novel and interesting experience. I was arrested last summer, about the end of July. I was walking into Concord to have my shoe repaired, and Sam Staples, the constable, stopped me, and said I had not paid my tax, which I knew. And he even offered to pay it for me. “Well,” I said “I am not hard up, it is just a principle.”

Richard Smith is an actor who portrays Henry David Thoreau for audiences in and around Concord. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

DOERING: That principle was that Thoreau refused to support slavery and the war against Mexico with his taxes.

SMITH: So he said he would have to lock me up; I said, “Well, now is as good a time as any, Sam.” So I was put in jail for the night.

DOERING: In the end, Thoreau’s aunt paid the tax, and he was released the next morning.

SMITH: I said to Sam that because I did not pay the tax, I should not have to go. But he said that they needed the room.

[AUDIENCE LAUGHS]

And so they had to let me go. But, because I was there due to my conscience, I felt that I was freer than any of my fellow Concordians who had paid the tax.

DOERING: Thoreau’s act of civil disobedience would inspire both Gandhi and the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the struggles against injustice they led many decades later. The essay and “Walden” have helped many discover their life’s passion, including Laura Dassow Walls, now an English literature professor and Thoreau biographer. She says when she was in high school, in the sixties, she felt lost.

WALLS: Didn’t feel like I belonged. Wasn’t quite sure who I was. And I found a little paperback book in a bookstore, had a green cover, and the title was “Walden and Civil Disobedience,” and I pulled it off and started to read it, and standing there in the bookstore was just captured by this voice.

DOERING: So she bought the book and carried it with her everywhere.

In an outdoor classroom, teachers examine jars of brownish water -- they were full of “pond glop” and held a surprising array of little organisms. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

WALLS: And during things like football rallies, where I had felt most isolated and alone – These were mandatory of course -- I would perform my act of civil disobedience by sitting on the grassy knoll where all the students and teachers would pass, and I would read my “Walden,” make sure that the cover was visible.

DOERING: And Thoreau’s words about charting one’s own course and going one’s own way helped her figure out who she was.

[Fleetwood Mac, "Go Your Own Way," on Rumours, written by Lindsey Buckingham, Warner Bros. Records]

WALLS: It’s not like a handbook, right? “Do this”. It is a way for you to figure out how to make the decisions about your life and your future by consulting your own innermost purpose and your own sense of what is right for you.

[Fleetwood Mac, "Go Your Own Way," on Rumours, written by Lindsey Buckingham, Warner Bros. Records]

Matt Burne holds up a spotted salamander for the teachers to see (Photo: Jenni Doering)

DOERING: Through “Walden,” “On Civil Disobedience,” and other works, Thoreau would have a profound impact on both individuals and intellectual life. But he is not easy reading.

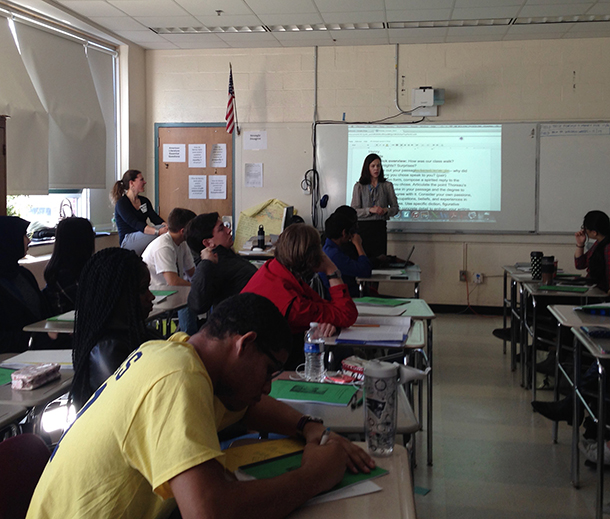

CONLON: My name is Carrie Conlon, and I teach at Lexington High School in Lexington, Massachusetts.

DOERING: After years of struggling with teaching Thoreau, Conlon briefly gave up.

CONLON: I took a couple years off from teaching “Walden”. I encountered some opposition from students, not only to the difficulty of the reading sometimes, but to kind of the message or the point of Thoreau’s visit to Walden, and the point of his writing “Walden”.

[SCHOOL BUS ATMOSPHERE]

DOERING: But visiting Walden Woods makes that easier, so on a grey November morning Conlon brings her students on a bumpy bus ride from nearby Lexington High School.

[STUDENTS WALKING AND TALKING QUIETLY]

Carrie Conlon teaches her Walden unit at Lexington High School. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CONLON: I just want them to walk in the actual places where Henry walked. I want them to walk on the soil that he walked upon. I want them to just enjoy being outside of the classroom, the experiential quality of what we’re doing.

DOERING: Some students grumble that Thoreau wasn’t as productive as he could have been, spending so much time observing the natural world.

CONLON: Because these are high-achieving kids, who do their homework, they want good grades, they value being busy. And so I think there’s still a little suspicion that he’s someone who’s just outside, sitting around. But they also can see that – We talked a lot about productive idleness, and being mindful about when you choose to do nothing, so it’s not just empty time, but it’s actually restorative. And I think that’s helped them understand where he’s coming from a little bit more.

[LEAVES CRUNCHING]

Students from Lexington High School walk through Walden Woods on a field trip (Photo: Jenni Doering)

DOERING: In fact, Thoreau was active in his environment, walking and chronicling in his twenty-four years of journals places as far away as Maine and Minnesota as well as his local landscape. As the students walk a woodland path where Thoreau himself might have trodden, ecologist Matt Burne of the Walden Woods Project asks the students about the trees here, the pitch pine, white birch, hickory, and oak.

BURNE: Does anyone have a sense of how old this forest probably is, just looking at it?

DOERING: Burne, who earlier schooled the teachers, is now face-to-face with the students.

STUDENT: I’d have to guess it’s about, maybe, 100-ish. 150 at most, I think.

DOERING: Another student disagrees.

Matt Burne describes for the students what Walden Woods would been like during Thoreau’s time. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

STUDENT 2: I’d have to say at least a few hundred, I mean, it’s not like he was walking around the Great Plains. There was a forest here, too when he was around and that was more than 100 years ago.

BURNE: No but a lot of it was cut down. So if you look at the trees here, none of these trees is much more than 40 years old.

DOERING: Burne explains that when Thoreau said, “I went to the woods,” he didn’t mean a wilderness.

BURNE: The woods that he went to was a very active wood. There would have been a lot of clearing throughout that forest. In Henry’s day, forest products were one of the most important things that the land was used for. So, up until the very early 1900s, the vast majority of Massachusetts, 90% of the landscape would have been cleared.

DOERING: But there was still plenty of nature in Walden Woods, and Thoreau felt closer to the essence of life here. Again, actor Richard Smith, channeling Thoreau’s transcendentalism.

Students climb Pine Hill, once one of Thoreau’s favorite huckleberry-picking spots. It’s an open, grassy hill where the Concord Water Department stores water in an underground reservoir. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

SMITH: When I look at a tree, when I look at a pond, when I look at all of nature, I feel as if I am looking directly into the face of God. Living in the woods I am surrounded by the divine. It is not only within me but it is without me as well.

DOERING: Thoreau’s writings left a record for future generations, which would serve also as a guide to protecting the wooded landscape he roamed. Kathi Anderson again.

ANDERSON: The importance of protecting Walden Woods is, you’re also preserving the literary legacy of the land that inspired Thoreau and his writings, and you’re creating a place where people can go and see what Thoreau experienced in his life.

DOERING: And for more than a hundred years, much of the woods were left alone and visited by Thoreau’s admirers. But by the 1980s, the rising price of real estate had developers seeing potential profits for two big projects on all that wooded land.

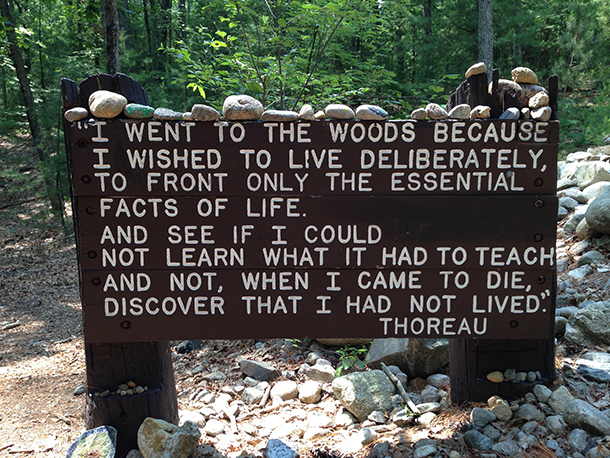

Near the site of Thoreau’s cabin is a sign bearing one of his most well-known quotes. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

ANDERSON: One was an office park, a 147,000 square foot office park. It was going to have parking for over 500 cars, and it was going to have a terrible impact on the historic and ecological integrity of Thoreau’s Walden Woods. The other was a condominium complex on the western border of Walden Woods.

DOERING: Local officials were faced with what seemed a zero-sum choice. Either cancel the projects and forgo the revenue they might bring, or greenlight the development and blot out key parts of the little nature left in this iconic place.

ANDERSON: I mean, Walden really is a symbol of conservation. If we can’t protect the place that gave birth to the idea of conservation, through Thoreau’s writings, how can we ever hope to protect other places around the world?

DOERING28: Fortunately a local group of citizens had faith in Thoreau’s original vision of a healthy balance between society and nature. They banded together and petitioned local regulators to block the project, battling criticism that preserving Walden Woods would shut out residents in need of moderately-priced housing in the booming area.

ANDERSON: But they did get their story out there on CNN. And Don Henley happened to be in his kitchen in Los Angeles, watching CNN, when the story appeared.

DOERING: That’s rock star Don Henley, of The Eagles.

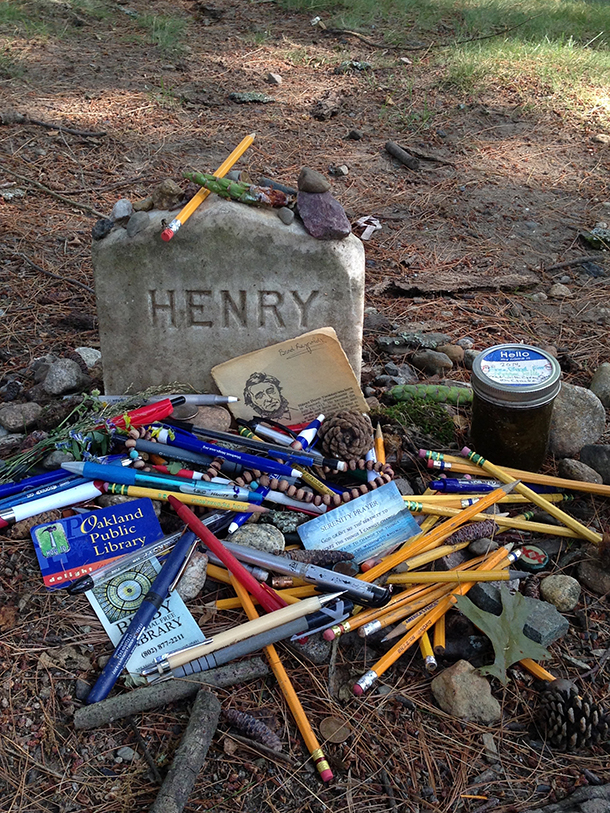

Visitors to Henry David Thoreau’s gravesite leave pencils and other gifts. For part of his life, Thoreau worked as a pencil-maker in his family’s business. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

ANDERSON: When he was in high school, and again in college, he had a couple of very influential teachers, who introduced him to Thoreau and Emerson’s writings, at a time when Don was really struggling with spirituality, questions of self-reliance, career decisions. He derived a great deal of support from reading Thoreau and Emerson. And it stayed with him for years and years and years.

[MUSIC STARTS QUIETLY.]

DOERING: So when Henley heard that the woods that had inspired Thoreau were threatened, he decided to act. Henley leveraged his rock-star status and popularity, organizing benefit concerts with other stars, where they played Eagles songs like “Desperado” and “Hotel California” –

[The Eagles, "Hotel California", live 1977 recording, originally released on Hotel California, Asylum Records]

[HENLEY (SINGING): On a dark desert highway, [SCREAMS FROM AUDIENCE] cool wind in my hair...]

DOERING: Don Henley has said “Hotel California,” the Eagles’ most popular song, was in part about excess and, quote, “the dark underbelly of the American dream.” Here’s an excerpt of what Thoreau wrote in “Walden” about essentially the same sickness in 19th-century America.

MAN READING WALDEN: The nation itself… is an unwieldy and overgrown establishment, cluttered with furniture and tripped up by its own traps, ruined by luxury and heedless expense, by want of calculation and a worthy aim…

DOERING: Don Henley and his friends ultimately raised $22 million for the Walden Woods Project, the nonprofit he founded in 1990. And the land the nonprofit safeguards isn’t just sitting there idly. It helps keep Thoreau’s legacy alive.

RETALLIC: The reason that this place was founded is because Thoreau was inspired by this place. And as a result Walden became this protected space that could inspire millions for years to come after him.

DOERING: Whitney Retallic, the project’s Director of Education, is at the heart of carrying on this legacy.

The reflection circle at Brister’s Hill bears quotes from John F. Kennedy, E.O. Wilson, Mohandas K. Gandhi, Aldo Leopold and more. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

RETALLIC: And so we ask students to think about – OK, the Walden Woods, Concord – That was Thoreau’s muse. Which natural space is your muse? Which place has inspired you? And if anything were to happen to that place – what would you do to protect it?

[MORE OUTDOOR SOUNDS, TREES RUSTLING, FOOTSTEPS ON PATH]

DOERING: Part of Walden Woods that was saved from development, Brister’s Hill, is bordered on one side by a major highway. Yet the forest dampens its din, and you can walk a trail called Thoreau’s path to a quiet reflection circle. Large granite blocks bear quotes from others who carried forth the torches of the conservation and justice movements, Gandhi, Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Muir, Rachel Carson, and more.

[FOOTSTEPS, TREES RUSTLING AMBI]

DOERING: I walk the circle of luminaries, and think of the children of today and tomorrow who might be inspired by Thoreau by walking through Walden Woods. I wonder what acts of civil disobedience they will be inspired to take up, how they might find their own ways to live deliberately, and what places they will help safeguard for future generations.

For Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering in Concord, Massachusetts.

Links

About the Walden Woods Project

NYTimes vintage, 1990: “Saving Thoreau’s Pond: Rock Stars (Who Else?)”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth