July 7, 2017

Air Date: July 7, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trump Rollback of Methane Rule Blocked

View the page for this story

The U.S Court of Appeals for the D.C Circuit ruled the Environmental Protection Agency cannot suspend a regulation that makes new oil and gas wells reduce methane leaks. The powerful greenhouse gas methane contributes to air pollution and damages public health. David Doniger, Director of the Climate and Clean Air program at the Natural Resources Defense Council who helped bring the suit and Host Steve Curwood discussed the significance of this ruling. (05:35)

Global Warming to Worsen Southern Poverty

View the page for this story

A new, interdisciplinary effort analyzed vast amounts of climate and economic data to forecast certain regions of the United States will be hit harder than others by global warming. Economist and lead author Solomon Hsiang of the University of California, Berkeley, told Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood the study estimates southern counties of the US, many of which are poor, could face a 20% decline in economic activity if carbon emissions continue unabated through the 21st century. (09:15)

Henry David Thoreau Turns 200

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

Walden Pond, where Henry David Thoreau famously ‘lived deliberately’ in a small hand-built cabin is popular, and Thoreau walked, thought, and observed in the surrounding woods. To protect them from development, conservationists, Thoreau scholars and even a rock star founded the Walden Woods Project. 200 years after Thoreau’s birth, Walden Woods now helps students and teachers learn about Thoreau, his philosophy and nature itself. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering went to the woods to find out how and why Thoreau’s legacy lives on (16:23)

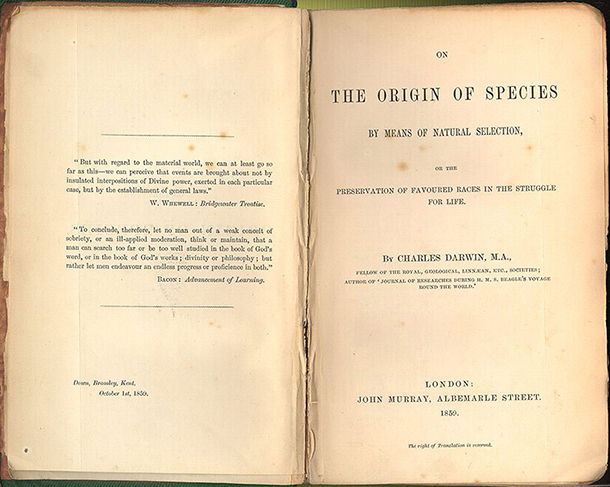

“The Book That Changed America”

View the page for this story

Is Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, says Randall Fuller, Professor of English at the University of Tulsa. Darwin’s book arrived in Boston and Concord, Massachusetts in 1860, as the slavery debate raged and civil war loomed, and its ideas were instantly fodder for those discussions. Randall Fuller explains the influence of Darwin’s new theories on Thoreau and his contemporaries with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer. (12:44)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Host Steve Curwood takes a trip Beyond the Headlines with Peter Dykstra to celebrate Germany’s achievement of 35% renewable power, and note how both nuclear power and clean coal are stumbling in Georgia. Also, thought it didn’t derail the project, it’s been 40 years since nearly fifteen hundred people were arrested protesting plans to build Seabrook Nuclear power plant. (02:45)

()

()

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: David Doniger, Solomon Hsiang, Randall Fuller

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Jenni Doering

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. An appeals court rules that EPA can’t suspend an Obama rule curbing methane from new wells and pipes.

DONIGER: There's really three kinds of pollution that come from these wells and pipes. There's methane, which is a very powerful global warming pollutant. There's hydrocarbons, which contribute to ozone smog. And then there's also specific hydrocarbons that can cause cancer.

CURWOOD Also, Henry David Thoreau was born 200 years ago, but his ideas and writing still inspire.

WALLS: And I found a little paperback book in a bookstore, had a green cover, and the title was “Walden and Civil Disobedience”. And I pulled it off and started to read it, and standing there in the bookstore was just captured by this voice.

CURWOOD Preserving the woods where Thoreau went to live deliberately. That and more, this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Trump Rollback of Methane Rule Blocked

The Obama-era Methane Rule, which the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C circuit ruled the EPA needed to uphold, requires new oil and gas wells to limit methane emissions. (Photo: Tommaso Galli, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

When first emitted methane is around 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide as a global warming gas. And in a setback to the Trump Administration’s push to roll back regulations, the U.S Court of Appeals for the D.C circuit has ruled that the E.P.A can’t suspend rules to control methane and other pollutants from new oil and gas wells. Some experts predict the Administration will also lose a case just filed by the attorneys general of California and New Mexico against the Interior Department’s suspension of a similar rule for public lands.

We turn now to David Doniger, a lawyer in the Clinton Administration who litigated the EPA case for his present employer, NRDC. Welcome to Living on Earth David.

DONIGER: Thanks. Nice to be here.

CURWOOD: Now, when the EPA announced it was suspending enforcement of the methane rule, what were the reasons that it gave for suspending, and what was it trying to accomplish?

DONIGER: Well, the oil and gas industry come to Pruitt, the EPA administrator, their long-time buddy from working with him as an Attorney General for Oklahoma, and they said, “Take this EPA rule away from us,” and Pruitt issued a stay, and the basis for the stay was a claim that the companies had not had a fair opportunity to comment a year ago when EPA initially issued the rule, and the Court of Appeals turned him down flat, saying that's all trumped up. They had plenty of opportunities to comment on each of the issues, and you don't have the authority to issue a stay of these regulations.

CURWOOD: Now, this isn't the only methane rule that industry is pushing back against. I gather there's also one that the Senate voted to maintain regarding methane coming from public lands. What's that rule exactly?

Scott Pruitt, the current EPA administrator, imposed a 90-day stay on his agency’s enforcement of the Methane Rule. A federal appeals court ruled the suspension was illegal. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DONIGER: Yeah, the Bureau of Land Management in the Interior Department also regulates the pollution from these drilling and processing operations when they occur on public lands, and that rule covers both new equipment and existing equipment, and it's grounded in a statute that tells the federal government to prevent the waste of methane, which means throwing the stuff away without getting proper royalties for it. Even though the Senate refused to to kill this rule, the Bureau of Land Management has decided to stay it, to suspend it indefinitely, while they work on a rule to repeal it, and this is illegal also.

CURWOOD: So, what does all this mean for the oil and gas industry, the Interior Department, the Bureau of Land Management, the EPA? What's going on here?

DONIGER: Well, the oil and gas industry is really split. There are a lot of companies that have complied with the rule already, they've done their leak detection. They're fixing leaks when they find them. And then there are others which are resisting, I think, out of a sort of cussedness that they don't want the federal EPA telling them what to do.

CURWOOD: How hard is it to limit emissions of methane from these oil and gas operations?

Former EPA attorney David Doniger is the Director of the Climate and Clean Air program at the Natural Resources Defense Council. (Photo: Courtesy of NRDC)

DONIGER: Well, limiting the emissions of methane is really simple. It's a matter of using infrared cameras to detect the leaks, and then you fix the problems that you found - a leaky valve, broken seal, something needs to be tightened up. This should be pretty simple stuff. It's just zipping it up. It's not requiring any major change in the design of the equipment. Compared to the billions of dollars in revenue from these oil and gas wells, the expense of checking to make sure they don't leak is pretty trivial.

CURWOOD: What are the public health risks of these emissions of methane?

DONIGER: There's really three kinds of pollution that come from these wells and the pipes that gather up the gas and take it the processing plants and so on. There's methane, which is a very powerful global warming pollutant. There's hydrocarbons which contribute to smog, and ozone smog is a problem in many of these, even in western areas which you think of as rural which have smog problems. And then there's also specific hydrocarbons like benzene and and other ones that are particularly toxic and cause cancer. So there are problems for the near neighbors, the communities in the region, and for the whole globe.

CURWOOD: So, what's going to happen next?

DONIGER: Well, in this case I think this is it. The court has issued its decision. EPA's unlikely to appeal it. The stay is gone. The rules are back in effect. Now, Scott Pruitt has to decide whether he wants to do the oil and gas industry the favor of issuing a stay or deferring enforcement in some other way, and we'll hold him into account if he does. There's many other actions that Pruitt and other cabinet officials have taken to yank rules in effect with no public process, and those actions are in danger now, and we're talking about rules for other air pollutants, for chemical plant safety, for pesticides. The Transportation Department, they've yanked some rules for carbon accounting in highway planning. The Interior Department is yanking their own methane rules and some others. The Occupational Health and Safety Administration has yanked some worker safety rules. All of these things now we may be able to hold the government to account.

CURWOOD David Doniger is Director of the Climate and Clean Air Program at the NRDC. Thanks so much for taking the time today, David.

DONIGER: Thanks a lot, Steve.

Related links:

- NYTimes | “Court Blocks E.P.A Effort to Suspend Obama-era Methane Rule”

- David Doniger, Natural Resources Defense Council

- Listen to Living on Earth’s report about the Senate saving a public lands Methane Rule

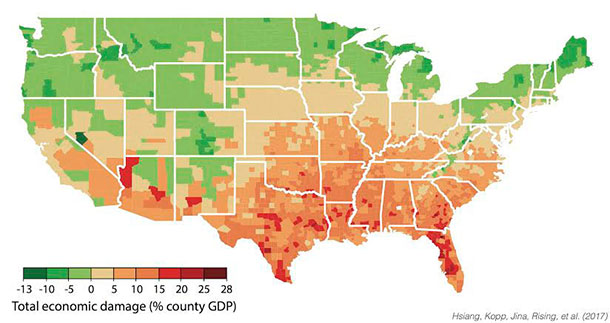

Global Warming to Worsen Southern Poverty

Airman 1st Class Jeffrey Albright beating back the heat wave at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada. (Photo: Master Sgt. Jason Edwards [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

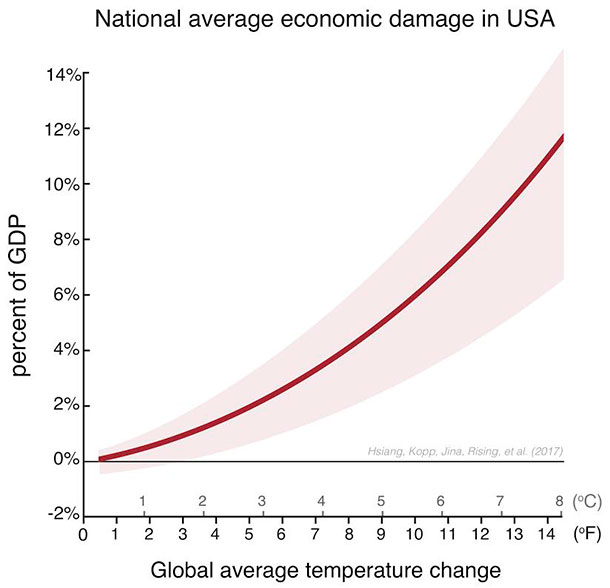

CURWOOD: Global warming is on track to devastate the US economy in years ahead if temperatures are allowed to rise unabated, this according to a study just published in the journal Science. Economists with the Climate Impact Lab project that the poorest third of counties in America would be most harmed, with incomes cut as much as 20 percent. The Lab is a consortium of experts from the Universities of California, Chicago, Rutgers, and the Rhodium Group, and this forecast used a wide variety of climate models and economic data.

Economist Solomon Hsiang was one of the lead researchers. He teaches public policy at UC Berkeley and joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

HSIANG: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: Now, which regions of the United States does your study predict will be hit hard in this climate disruption scenario?

HSIANG: That’s actually one of the most interesting and surprising findings of this study. What we found is that the southern United States, southern parts of the Midwest, and also the Atlantic coast are some of the most hardest hit parts of the country. There's a pretty good explanation for that once we did the analysis, and we understood was going on.

What happens is that the economic impact of warming is much worse if you are already pretty hot. So you can imagine going from 90 to 95 degrees is a much bigger deal going from 70 to 75 degrees. And so, because the southern parts the country are already so warm, a bit of warming does a lot more harm to them then to the northern parts of the country that tend to be cooler, and in some cases even places along the north can benefit. Places along the border with Canada are so cold that there actually, you know, they have people who are getting sick from it being so cold, and this is an important finding because the northern parts the country tend to be wealthier today, and the southern parts of the country tend to be poorer. So, by hurting the south more you're really hurting the poor population in the country relatively more, and this, we think, means inequality within the country could actually worsen.

Climate Lab study prediction of economic damage by U.S. County. (Photo: Courtesy of Kathleen Maclay)

CURWOOD: Talk to me about that inequality. How much money are we talking about here?

HSIANG: Well, we're talking about places in the south that could possibly experience losses between 10 and 20 percent of their income in sort of a central case. Now, it's very hard to predict the future, so what we've done is we’ve actually thought about is actually a range of different scenarios that might occur, and so in some cases it gets actually much higher than that, and in some cases it gets lower, but the central case for the South - large swaths of the South – to lose between 10 and 20 percent. And that's a lot, it could actually be much worse than what was experienced during the Great Recession in the United States and it's not that different from what parts of the Midwest experienced during the dustbowl.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about those regions that you say will have modest benefits. It sounds like they are going to be making more money.

HSIANG: So, there are parts of the United States that could benefit from some warming, although those gains are more hazy in the data becomes they’re sort of mild benefits but those are areas where you might save because you don't have to heat your house as much if things get a little bit warmer. So, those are places in the Rockies or along the northern border with Canada as well as New England. We looked at all different aspects of the economy and there's one place where the north actually gets hit worse than in the south.

CURWOOD: Oh?

HSIANG: [LAUGHS] When you look at property crime. It turns out that the only way that the climate really affects property crime rates across the country is that when it's really cold and there's a lot of snow on the ground, nobody goes out and really takes each other's stuff. No one steals a car when it's covered in snow. So, right now, the north gets a lot of cold days and a lot of snow that protects it from this type of impact, but in the future, as things warm up, it loses that protective cold, and so you actually see property crime rates rise in the north, but essentially nothing happens in the south.

CURWOOD: What about violent crime rates in your scenario?

HSIANG: So, we also studied violent crime, and violent crime responds to the environment very differently than property crime. We actually see that if you warm up populations - and this is actually true outside the US as well - we see violent crime rates go up very steadily pretty much for everyone. It doesn't matter what your initial temperature is. So, we see violent crime rates rise by about five percent across the entire country.

CURWOOD: Looking at some of the maps and charts that you have with your study, it looks like south Texas and Florida are really going to be in trouble in a warming scenario. How much trouble, exactly, for those places would you predict?

HSIANG: Those other parts of the country where you could be seeing counties losing upwards of 20 percent of their income, and that's due to the combination of what we talked about before, that those places are really hot and so getting hotter is extremely costly. But there's an additional issue that arises along the Gulf Coast which is the effects of sea level rise interacting with hurricanes, and so places like Texas, Louisiana, and Florida end up having really large costs along their coastlines due to the fact that, as the sea level rises go up, the storms that arrive are going to have bigger surges, and in the future we expect to have a changing pattern of hurricanes where sometimes there will be more of them and sometimes they will be stronger, and so that can increase the economic losses, you know, year over year for those reasons quite substantially.

Climate Lab study forecast of national average economic damage in the U.S. (Photo: Courtesy of Kathleen Maclay)

CURWOOD: So, your research, then, is indicating in a general way as well as those specific places that the regions are going to have the most economic damages from climate disruption are presently very politically conservative strongholds. To what extent do you think your research might be able to, well, change the discussion with those lawmakers and their constituents?

HSIANG: Well, first just to be clear, all of our work was completely unrelated to the current political landscape. We've been working on this for many, many years. We didn't know these types of results until now, so the fact that people might not have taken these economic consequences into account in making their previous judgments about, or in terms of how much they're concerned about and want to change, maybe that's OK. Nobody knew that this was going to be what we saw in the data, but what we're hoping is that now the public can have a well-informed dialogue about how we want to manage the climate, based on what we can see at least at this point about what might be lying ahead.

CURWOOD: So, how can you research be used to come up with, say, a more accurate social cost of carbon, a metric that can inform, perhaps, legislation, maybe carbon tax, other types of policies?

HSIANG: Yeah, a lot of our work is exactly aiming at trying to inform the social cost of carbon. The social cost of carbon doesn't just reflect what people in Oklahoma or California are going to feel. It also reflects the fact that when I drive my car here in California, the carbon dioxide goes up into the atmosphere, circles the planet over 80 times and is affecting people all over the world, and so we are undertaking a major effort to take what we've learned from this analysis and expand it to the whole world, and then we'll be using those numbers to compute the social cost of carbon that could be used by regulators in any country really, not just the United States.

This analysis, we show that the southern United States is the most heavily impacted because it hot relative to the north, but if you keep going south it just keeps getting hotter and hotter. So, you think about Mexico, Central America, these places are going to experience these things even more intensely than the American south, and so it's really important that we understand coming ahead for them and that we account for those losses to the global society.

CURWOOD: What about population increase? Here in United States we go from roughly 300 million people at the turn-of-the-century back there in the year 2000. By the middle of the century, it's projected will be over 400 million people. The effects of climate disruption reducing the economic prospects of folks in the south, plus the population rise, equals what, do you think?

Solomon Hsiang is an Associate Professor of Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley. (Photo: Courtesy of Kathleen Maclay)

HSIANG: Yeah, so one of the major challenges in economics generally as a field is just how do we maintain living standards and well-being for a population that's growing. It takes more resources to support more people moving ahead into the future, and so what you try to do is maintain economic growth, which allows us to produce more material assets at least as fast as the population is growing, because, if you just have more people in a place with a same number of material assets, then you have to start subdividing them more and more and more and everyone becomes a little poorer.

What climate change does is, it actually slows down the economic growth rate. It puts like a handicap on us in this race between economic growth and population growth, and so it makes it even harder. We have to be even more innovative. We have to work harder, and so what I think climate change is going to do is make it a lot harder to meet the standards of living that people expect, particularly in the regions that are hardest hit. So, people really dislike having long periods of unemployment or having longer recessions, and the way I put it to some folks is that climate change is something that's on scale bigger than a recession except it doesn't just go away, it’s not like we just recover from it. Once you have it, it's here to stay and so we think about whether or not we can make changes today that will avoid those types of outcomes, and those are the types of questions we should be asking ourselves.

CURWOOD: Solomon Hsiang is an economist and Associate Professor of Public Policy of the University of California, Berkeley. Thank you so much, Professor, for taking the time today.

HSIANG: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Science: “Estimating economic damage from climate change in the United States”

- Solomon Hsiang Faculty Profile

- The Climate Impact Lab

[MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0CFuCYNx-1g Stevie Wonder, “Superstition”]

CURWOOD: Coming up –Two hundred candles for a most significant philosopher of the natural world. Keep listening Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?annotation_id=annotation_361546991&feature=iv&src_vid=OLqD8u3eFeM&v=RUnQ_y0b4fs Stevie Wonder, “Superstition”]

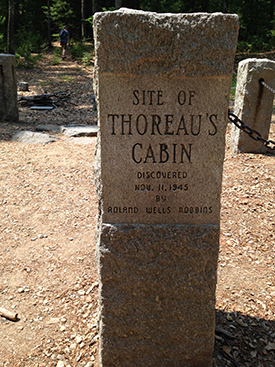

Henry David Thoreau Turns 200

The site of Thoreau’s cabin in Walden Woods. On the left is a pile of stones left by Thoreau’s admirers, which grows year by year, and on the right are the granite blocks marking the cabin site. (Photo: Bill Illot, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Henry David Thoreau was a great nature writer and thinker, and if he were still alive, he’d celebrate his two hundredth birthday on July 12th. Thoreau was not widely read in his lifetime, yet his book “Walden” has become an American classic, and his essay “Civil Disobedience” inspired non-violent leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi and the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. 200 years after Thoreau’s birth, his legacy lives on, not only in his complex prose, but also in the woods of Concord, Massachusetts around Walden Pond. He famously wrote about his two years living there in a simple hut, though he frequently went home to his mother to get his laundry done and for a home-cooked meal.

Conservationists, scholars, teachers, even a rock star have helped preserve the legacy of Thoreau and Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering went to the woods to find out how and why they’re keeping the sage of Walden alive.

Walden Pond turns into a pleasant swimming hole in summer – but it has historical significance, too. (Photo: Oleg., Flickr CC BY 2.0)

[SPLASHING, WATER LAPPING AT SHORE, LAUGHING, LIFEGUARDS, FOOTSTEPS IN SAND]

DOERING: In summer, Walden Pond is a cool and deep, blue-green oasis surrounded by broadleaf forest, the verdant trees in full leaf. A pleasant sandy beach curves along its eastern shore, where lifeguards watch over children and adults who venture in for a swim.

[CHILDREN PLAYING, SWIMMING SOUNDS]

DOERING: But this is no ordinary swimming hole. It’s just down the road from the town of Concord, where Henry David Thoreau and other transcendentalists like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, and Nathaniel Hawthorne developed their philosophy. In close proximity to these luminaries and as the location of the cabin where Thoreau “lived deliberately” for two years, Walden has been called the birthplace of the American conservation movement.

[CHILDREN PLAYING, SWIMMING SOUNDS]

DOERING: Yet it wasn’t a trackless, remote wilderness then, and, just a short drive from Boston, it’s now visited by nearly 700,000 people each year.

[SOUNDS OF WALKING]

Many walk the path that winds along its shore to the site of Thoreau’s cabin, the simple 10 by15 wood structure long gone, but its original location marked by granite blocks, and an impressive pile of stones left in tribute to the writer that grows, year by year.

Thoreau built his cabin near the shore of Walden Pond in 1845 from repurposed wood. When Thoreau left two years later and no longer needed the cabin, a local farmer took it apart and put the wood to use on his farm. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

But the pond and nearby cabin are just the tip of the iceberg, says Kathi Anderson, the Executive Director of the Walden Woods Project.

ANDERSON: Thoreau lived in the woods. And while his cabin was on the shores of Walden Pond, he spent most of his life walking around the woods of Walden Woods.

DOERING: Anderson’s nonprofit was founded in part to protect those woods, which have diminished over the years. A major highway now bisects Walden Woods, and the town of Concord’s old landfill sits where Thoreau used to roam. But the Walden Woods Project also exists to carry on Thoreau’s legacy of reconnecting people with the outdoors. Anderson says, today that’s needed more urgently than ever.

ANDERSON: There’s a disconnect between kids and nature. And we have to reconnect that.

[OUTDOOR CLASSROOM SOUND]

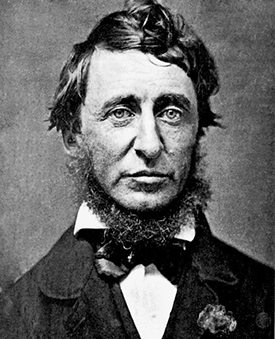

Daguerrotype of Henry David Thoreau in June 1856. (Photo: Benjamin D. Maxham, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

DOERING5 In the woods not far from the pond, I see the seeds of that reconnection being planted, with the help of several mason jars, full of brownish water.

BURNE: These jars that are on the table that are kind of murky. This is what we call pond glop.

[CROWD GIGGLES]

WOMAN: Is that a technical term?

[MORE LAUGHS]

BURNE: Yeah, it sure is.

DOERING: Ecologist Matt Burne and twenty or so adults sit in the shade in a clearing in the woods. They’re teachers, here to learn. One woman asks Burne what the curious little creature in her mason jar of pond scum is.

WOMAN: It’s like this little red squiggle.

BURNE: Oh the red squiggle. That’s a chironomid midge larvae. It’s a flying insect.

DOERING: They seem fascinated by the little creatures in their jars, and some others that Burne collected from the forest nearby: a wood frog, a water scorpion, a red-spotted newt, and a spotted salamander. They’re art teachers, science teachers, and even an elementary school librarian. The Walden Woods Project is schooling these teachers in how to bring their students outdoors – or, to bring the outdoors in -- using Thoreau as a guide. They even get to meet the man himself.

SMITH: I am living at the pond to meet life, be it good or be it bad.

DOERING: Richard Smith does a professional impression of Henry David Thoreau, and all of a sudden it’s a warm July day in 1847.

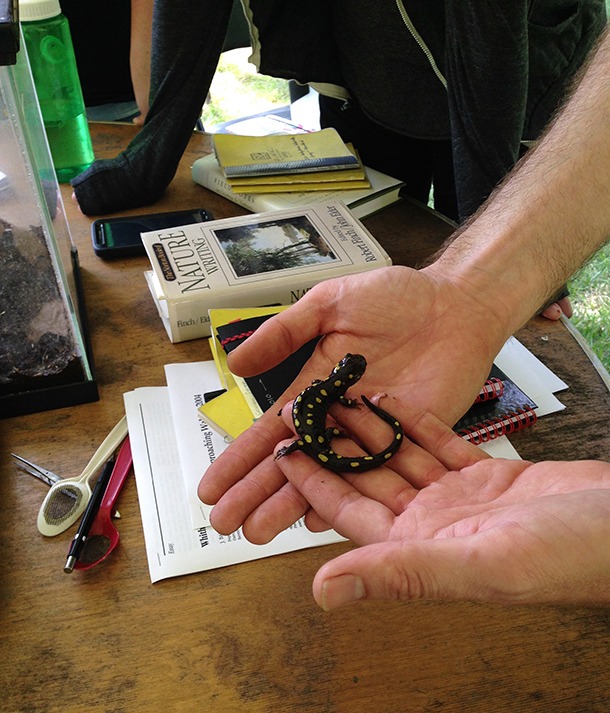

Matt Burne, the Conservation Director of the Walden Woods Project, instructs a class of teachers about how to bring the outdoors into their classrooms. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

SMITH: I felt that for too long, I was the observer of my life and not the participant.

DOERING: Smith sports a beard just around his chin, reminiscent of Thoreau’s style, and wears a tweed vest and trousers. He keeps a straight face as he channels Thoreau’s kind of dry humor.

SMITH: Have you seen Mr. Emerson’s house, over on the Cambridge Turnpike?

AUDIENCE: Yes, sir.

SMITH: I live in very dangerous prosperity when I am over there. [AUDIENCE LAUGHS]

DOERING: Enjoying plenty of solitude at Walden Pond gave Thoreau the space to reflect on the injustices in his society. One teacher asks him to tell them about the night he spent in jail, which he describes in his famous essay, “On the Duty of Civil Disobedience.”

SMITH: Oh, have you been to jail?

[AUDIENCE LAUGHS]

It is a novel and interesting experience. I was arrested last summer, about the end of July. I was walking into Concord to have my shoe repaired, and Sam Staples, the constable, stopped me, and said I had not paid my tax, which I knew. And he even offered to pay it for me. “Well,” I said “I am not hard up, it is just a principle.”

Richard Smith is an actor who portrays Henry David Thoreau for audiences in and around Concord. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

DOERING: That principle was that Thoreau refused to support slavery and the war against Mexico with his taxes.

SMITH: So he said he would have to lock me up; I said, “Well, now is as good a time as any, Sam.” So I was put in jail for the night.

DOERING: In the end, Thoreau’s aunt paid the tax, and he was released the next morning.

SMITH: I said to Sam that because I did not pay the tax, I should not have to go. But he said that they needed the room.

[AUDIENCE LAUGHS]

And so they had to let me go. But, because I was there due to my conscience, I felt that I was freer than any of my fellow Concordians who had paid the tax.

DOERING: Thoreau’s act of civil disobedience would inspire both Gandhi and the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the struggles against injustice they led many decades later. The essay and “Walden” have helped many discover their life’s passion, including Laura Dassow Walls, now an English literature professor and Thoreau biographer. She says when she was in high school, in the sixties, she felt lost.

WALLS: Didn’t feel like I belonged. Wasn’t quite sure who I was. And I found a little paperback book in a bookstore, had a green cover, and the title was “Walden and Civil Disobedience,” and I pulled it off and started to read it, and standing there in the bookstore was just captured by this voice.

DOERING: So she bought the book and carried it with her everywhere.

In an outdoor classroom, teachers examine jars of brownish water -- they were full of “pond glop” and held a surprising array of little organisms. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

WALLS: And during things like football rallies, where I had felt most isolated and alone – These were mandatory of course -- I would perform my act of civil disobedience by sitting on the grassy knoll where all the students and teachers would pass, and I would read my “Walden,” make sure that the cover was visible.

DOERING: And Thoreau’s words about charting one’s own course and going one’s own way helped her figure out who she was.

[Fleetwood Mac, "Go Your Own Way," on Rumours, written by Lindsey Buckingham, Warner Bros. Records]

WALLS: It’s not like a handbook, right? “Do this”. It is a way for you to figure out how to make the decisions about your life and your future by consulting your own innermost purpose and your own sense of what is right for you.

[Fleetwood Mac, "Go Your Own Way," on Rumours, written by Lindsey Buckingham, Warner Bros. Records]

Matt Burne holds up a spotted salamander for the teachers to see (Photo: Jenni Doering)

DOERING: Through “Walden,” “On Civil Disobedience,” and other works, Thoreau would have a profound impact on both individuals and intellectual life. But he is not easy reading.

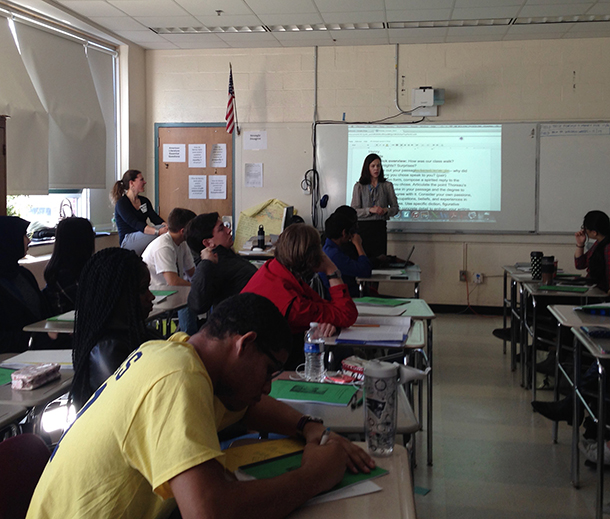

CONLON: My name is Carrie Conlon, and I teach at Lexington High School in Lexington, Massachusetts.

DOERING: After years of struggling with teaching Thoreau, Conlon briefly gave up.

CONLON: I took a couple years off from teaching “Walden”. I encountered some opposition from students, not only to the difficulty of the reading sometimes, but to kind of the message or the point of Thoreau’s visit to Walden, and the point of his writing “Walden”.

[SCHOOL BUS ATMOSPHERE]

DOERING: But visiting Walden Woods makes that easier, so on a grey November morning Conlon brings her students on a bumpy bus ride from nearby Lexington High School.

[STUDENTS WALKING AND TALKING QUIETLY]

Carrie Conlon teaches her Walden unit at Lexington High School. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CONLON: I just want them to walk in the actual places where Henry walked. I want them to walk on the soil that he walked upon. I want them to just enjoy being outside of the classroom, the experiential quality of what we’re doing.

DOERING: Some students grumble that Thoreau wasn’t as productive as he could have been, spending so much time observing the natural world.

CONLON: Because these are high-achieving kids, who do their homework, they want good grades, they value being busy. And so I think there’s still a little suspicion that he’s someone who’s just outside, sitting around. But they also can see that – We talked a lot about productive idleness, and being mindful about when you choose to do nothing, so it’s not just empty time, but it’s actually restorative. And I think that’s helped them understand where he’s coming from a little bit more.

[LEAVES CRUNCHING]

Students from Lexington High School walk through Walden Woods on a field trip (Photo: Jenni Doering)

DOERING: In fact, Thoreau was active in his environment, walking and chronicling in his twenty-four years of journals places as far away as Maine and Minnesota as well as his local landscape. As the students walk a woodland path where Thoreau himself might have trodden, ecologist Matt Burne of the Walden Woods Project asks the students about the trees here, the pitch pine, white birch, hickory, and oak.

BURNE: Does anyone have a sense of how old this forest probably is, just looking at it?

DOERING: Burne, who earlier schooled the teachers, is now face-to-face with the students.

STUDENT: I’d have to guess it’s about, maybe, 100-ish. 150 at most, I think.

DOERING: Another student disagrees.

Matt Burne describes for the students what Walden Woods would been like during Thoreau’s time. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

STUDENT 2: I’d have to say at least a few hundred, I mean, it’s not like he was walking around the Great Plains. There was a forest here, too when he was around and that was more than 100 years ago.

BURNE: No but a lot of it was cut down. So if you look at the trees here, none of these trees is much more than 40 years old.

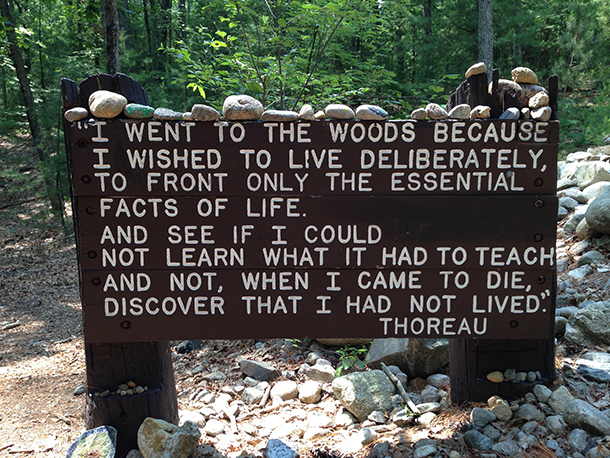

DOERING: Burne explains that when Thoreau said, “I went to the woods,” he didn’t mean a wilderness.

BURNE: The woods that he went to was a very active wood. There would have been a lot of clearing throughout that forest. In Henry’s day, forest products were one of the most important things that the land was used for. So, up until the very early 1900s, the vast majority of Massachusetts, 90% of the landscape would have been cleared.

DOERING: But there was still plenty of nature in Walden Woods, and Thoreau felt closer to the essence of life here. Again, actor Richard Smith, channeling Thoreau’s transcendentalism.

Students climb Pine Hill, once one of Thoreau’s favorite huckleberry-picking spots. It’s an open, grassy hill where the Concord Water Department stores water in an underground reservoir. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

SMITH: When I look at a tree, when I look at a pond, when I look at all of nature, I feel as if I am looking directly into the face of God. Living in the woods I am surrounded by the divine. It is not only within me but it is without me as well.

DOERING: Thoreau’s writings left a record for future generations, which would serve also as a guide to protecting the wooded landscape he roamed. Kathi Anderson again.

ANDERSON: The importance of protecting Walden Woods is, you’re also preserving the literary legacy of the land that inspired Thoreau and his writings, and you’re creating a place where people can go and see what Thoreau experienced in his life.

DOERING: And for more than a hundred years, much of the woods were left alone and visited by Thoreau’s admirers. But by the 1980s, the rising price of real estate had developers seeing potential profits for two big projects on all that wooded land.

Near the site of Thoreau’s cabin is a sign bearing one of his most well-known quotes. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

ANDERSON: One was an office park, a 147,000 square foot office park. It was going to have parking for over 500 cars, and it was going to have a terrible impact on the historic and ecological integrity of Thoreau’s Walden Woods. The other was a condominium complex on the western border of Walden Woods.

DOERING: Local officials were faced with what seemed a zero-sum choice. Either cancel the projects and forgo the revenue they might bring, or greenlight the development and blot out key parts of the little nature left in this iconic place.

ANDERSON: I mean, Walden really is a symbol of conservation. If we can’t protect the place that gave birth to the idea of conservation, through Thoreau’s writings, how can we ever hope to protect other places around the world?

DOERING28: Fortunately a local group of citizens had faith in Thoreau’s original vision of a healthy balance between society and nature. They banded together and petitioned local regulators to block the project, battling criticism that preserving Walden Woods would shut out residents in need of moderately-priced housing in the booming area.

ANDERSON: But they did get their story out there on CNN. And Don Henley happened to be in his kitchen in Los Angeles, watching CNN, when the story appeared.

DOERING: That’s rock star Don Henley, of The Eagles.

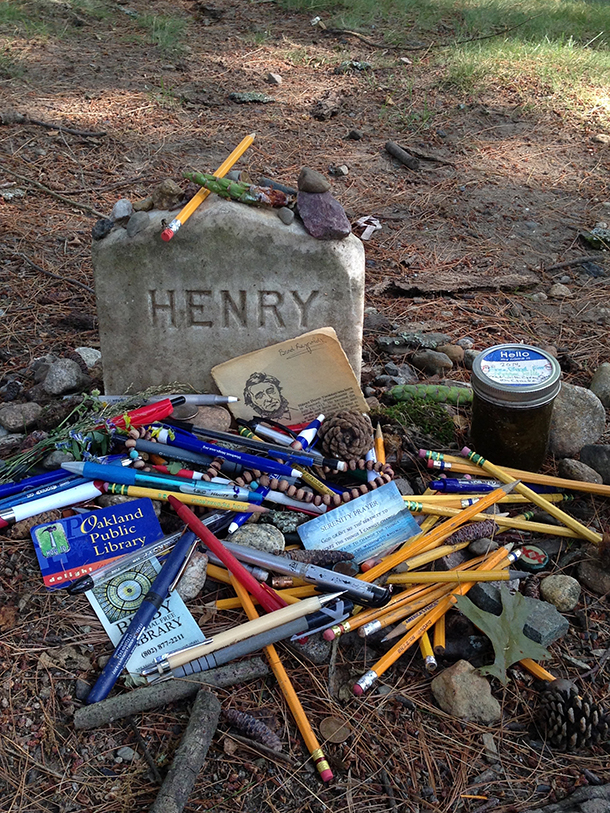

Visitors to Henry David Thoreau’s gravesite leave pencils and other gifts. For part of his life, Thoreau worked as a pencil-maker in his family’s business. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

ANDERSON: When he was in high school, and again in college, he had a couple of very influential teachers, who introduced him to Thoreau and Emerson’s writings, at a time when Don was really struggling with spirituality, questions of self-reliance, career decisions. He derived a great deal of support from reading Thoreau and Emerson. And it stayed with him for years and years and years.

[MUSIC STARTS QUIETLY.]

DOERING: So when Henley heard that the woods that had inspired Thoreau were threatened, he decided to act. Henley leveraged his rock-star status and popularity, organizing benefit concerts with other stars, where they played Eagles songs like “Desperado” and “Hotel California” –

[The Eagles, "Hotel California", live 1977 recording, originally released on Hotel California, Asylum Records]

[HENLEY (SINGING): On a dark desert highway, [SCREAMS FROM AUDIENCE] cool wind in my hair...]

DOERING: Don Henley has said “Hotel California,” the Eagles’ most popular song, was in part about excess and, quote, “the dark underbelly of the American dream.” Here’s an excerpt of what Thoreau wrote in “Walden” about essentially the same sickness in 19th-century America.

MAN READING WALDEN: The nation itself… is an unwieldy and overgrown establishment, cluttered with furniture and tripped up by its own traps, ruined by luxury and heedless expense, by want of calculation and a worthy aim…

DOERING: Don Henley and his friends ultimately raised $22 million for the Walden Woods Project, the nonprofit he founded in 1990. And the land the nonprofit safeguards isn’t just sitting there idly. It helps keep Thoreau’s legacy alive.

RETALLIC: The reason that this place was founded is because Thoreau was inspired by this place. And as a result Walden became this protected space that could inspire millions for years to come after him.

DOERING: Whitney Retallic, the project’s Director of Education, is at the heart of carrying on this legacy.

The reflection circle at Brister’s Hill bears quotes from John F. Kennedy, E.O. Wilson, Mohandas K. Gandhi, Aldo Leopold and more. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

RETALLIC: And so we ask students to think about – OK, the Walden Woods, Concord – That was Thoreau’s muse. Which natural space is your muse? Which place has inspired you? And if anything were to happen to that place – what would you do to protect it?

[MORE OUTDOOR SOUNDS, TREES RUSTLING, FOOTSTEPS ON PATH]

DOERING: Part of Walden Woods that was saved from development, Brister’s Hill, is bordered on one side by a major highway. Yet the forest dampens its din, and you can walk a trail called Thoreau’s path to a quiet reflection circle. Large granite blocks bear quotes from others who carried forth the torches of the conservation and justice movements, Gandhi, Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Muir, Rachel Carson, and more.

[FOOTSTEPS, TREES RUSTLING AMBI]

DOERING: I walk the circle of luminaries, and think of the children of today and tomorrow who might be inspired by Thoreau by walking through Walden Woods. I wonder what acts of civil disobedience they will be inspired to take up, how they might find their own ways to live deliberately, and what places they will help safeguard for future generations.

For Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering in Concord, Massachusetts.

Related links:

- About the Walden Woods Project

- NYTimes vintage, 1990: “Saving Thoreau’s Pond: Rock Stars (Who Else?)”

- The Thoreau Society Bicentennial celebration in Concord

- Meet Henry David Thoreau, thanks to actor Richard Smith

[MUSIC: Leo Patkovic, "Hotel California", not commercially available, written by The Eagles]

CURWOOD: Coming up... The book on biology that helped spawn a revolution in humanism. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jay Ungar and Molly Mason, “Ashokan Farewell” on Civil War Classics, Fiddle and Dances Records]

“The Book That Changed America”

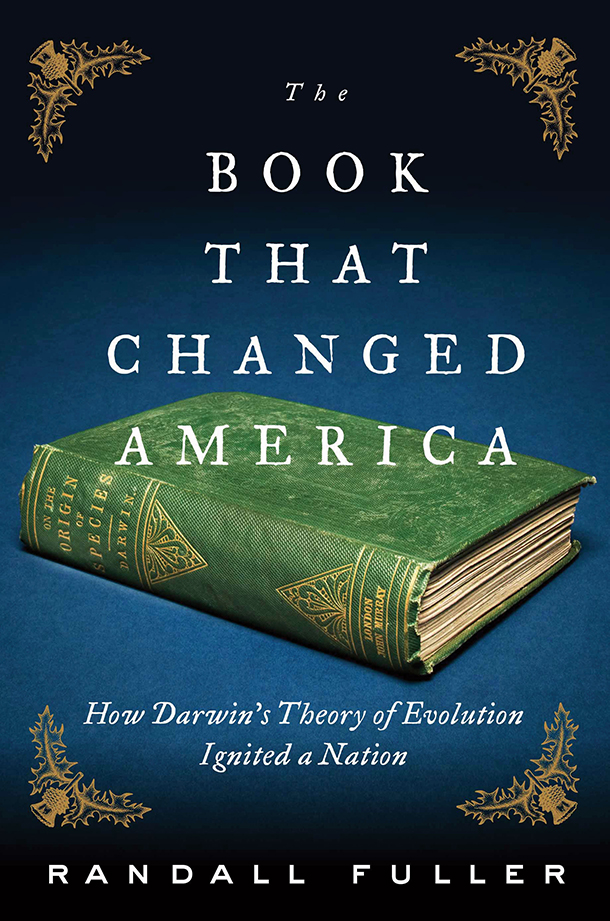

The Book That Changed America: How Darwin’s Theory of Evolution ignited a Nation. (Photo: Randall Fuller)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Henry David Thoreau was born into a century that changed scientific understanding, and society, and writer Randall Fuller argues that no single book was more influential than Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species”. He calls it “The Book That Changed America”, and writes that, when it came out in 1859, the debate about slavery was raging and civil war loomed. Its revolutionary thesis challenged, excited, and infuriated the intellectual elite and Thoreau was an early believer.

Randall Fuller teaches English at the University of Tulsa, and he spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

PALMER: So Randall Fuller, you subtitle your book, “How Darwin’s Theory of Evolution Ignited a Nation”. When “On the Origin of Species” arrived in the New England, the slavery debate was already pretty red-hot. How did Darwin’s theories play into that debate?

FULLER: Well, you're right. The divisiveness over slavery was already bubbling over as a result of the John Brown affair, but what Darwin's book did was enter a cultural moment where questions of competition between regions and especially the relative status of black people versus white people was incredibly heated and contentious, and so, what Darwin did essentially was bring to an already very fractious and volatile moment a new take on an old discussion about racial ideology and slavery.

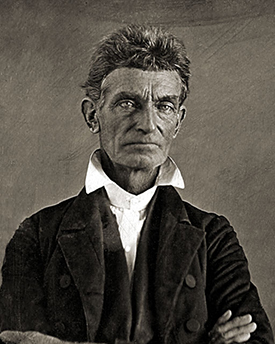

PALMER: Now you mention the John Brown affair. Can you tell me exactly what that was?

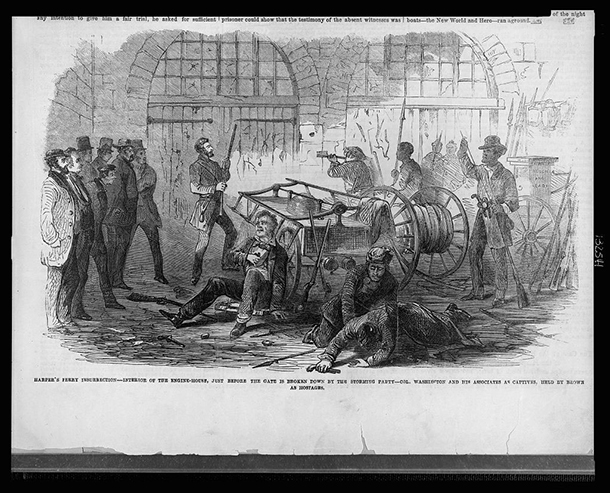

FULLER: In October of 1859, just as Darwin was finishing his book, John Brown led a small band of white and black rebels, as it were, to raid a federal armory in Virginia, in the hopes of releasing weapons to the slave population and fomenting a slave rebellion. The rebellion went horribly wrong. Brown was injured and imprisoned almost immediately. And in December 2nd, in a widely publicized trial, he was executed. And that trial galvanized American opinion about slavery. It intensified animosity throughout the two regions, the north and the south, and it occurred just as Darwin's book was arriving on these shores.

PALMER: Before we leave the issue of Harper’s Ferry, I'd like you to read a piece of your book, if you wouldn't mind. It's on page 220. I think one of the important things about this is that it's almost the thesis of the book.

Daguerrotype of Henry David Thoreau in June 1856. (Photo: Benjamin D. Maxham, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

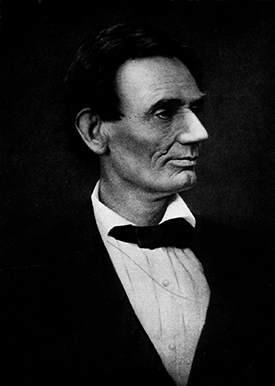

FULLER: Yeah, the argument here is that, if John Brown had not attempted his raid on Harper's Ferry, a whole sequence of domino effects might not have occurred, and likely Lincoln would not have won the election, and so Brown's raid is really a seminal moment in American history that led to Lincoln's election and also led after Lincoln's election to the dissolution of the Union.

PALMER: If you could read that, please.

FULLER: Lincoln's ascendance to the country's highest office was a direct result of Brown's attack on Harper's Ferry which had divided Democrats and left them without a viable candidate. During the summer of 1860, while debates over Darwin's theory reached their apex, America's pro-slavery press had vilified Lincoln, using his ungainly visage in countless cartoons. Lincoln was portrayed as a suitor of black women or as the missing link between blacks and whites. Sometimes he was even a gorilla -- Ape Lincoln.

After the election, the south immediately revolted. Former Democratic President James Buchanan addressed Congress to complain of ‘the long continued and intemperate interference of the northern people with the question of slavery in the southern states. The different sections of Union are now irate against each other, and the time has arrived, so much dreaded by the father of his country when hostile geographical parties have been formed.’ Buchanan was referring specifically to a series of rallies held throughout the south in support of secession. But his language made use of the same powerful metaphors of struggle and extinction that had appeared a year earlier in the “Origin of the Species”.

PALMER: That's a very interesting to me argument. That, in fact, the importance of Harper's Ferry was indeed to give you Lincoln the president and ultimately the Civil War and emancipation.

FULLER: That's exactly right, and I suppose one of the things I was getting at with my book was the way a kind of cultural configuration had already developed itself in the US. And so, when Darwin's book arrives in early December 1859, it's as though it explains everything going on in the United States about race, but also about the enormous divisions and competition between the two regions.

Charles Darwin, age 51 (Photo: Messrs. Maull and Fox, from book by Karl Pearson, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

PALMER: And also this whole question of whether or not man is one race or many races. “On the Origin of Species,” obviously suggests that ever-fitter, ever-fitter variations on any species are coming along, suggests that man is heading towards a more perfect being, and where do slaves or where do black people fit in that?

FULLER: That's the primary conversation that Darwin's book contributed to in the first year of its arrival in the US, and we often forget that, that in the 1840s a dominant scientific strain of thinking about human races had become prominent. The so-called “American ethnologists” argued that the various races had been created separately and in different places. The white race was the best that God had managed to do. Other races were sort of trial experimental efforts that hadn't gone quite as well as he had initially hoped, and of course this was enormously satisfying to the Southern slave powers. And Darwin enters into that debate by suggesting that all creatures, including human beings, share common ancestors and that, in point of fact, blacks and whites are not separate species or differently created humans but are, in fact, brothers and sisters.

PALMER: So, that's obviously gives an enormous goose to the anti-slavery forces because here is another child of God in chattel slavery.

1859 edition of Darwin's Origin of Species. (Photo: Author unknown, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

FULLER: That's exactly right. So, my contention is that Darwin's book initially arrives in this country and really just spreads like wildfire. "On the Origin of Species" is published in the US a month after the British edition arrives, and it's described in all sorts of newspapers and periodicals within the first month or so. But the reason it has such widespread readership and interest had to do with the slavery question first and foremost.

PALMER: Now, it was Asa Gray that first brought Darwin to this country. Who was Asa Gray? And how was he important in spreading the ideas?

FULLER: Asa Gray was the first botanist at Harvard College, and he was a world-class, largely self-taught scientist who had been in correspondence with Charles Darwin throughout the 1850s. Darwin, he liked to ask Gray questions about botany because he himself was more of a zoologist, and throughout the 1850s Asa Gray provided loads of evidence and examples for Darwin, which eventually made their way into "On the Origin of Species."

A daguerreotype of John Brown produced by John Bowles, c. 1856. (Photo: John Bowles, Boston Athenaeum public domain)

In the late 1850s, a little-known scientist named Alfred Russell Wallace on his own independently came up with the exact same theory of natural selection that Darwin had come up with, and Darwin was crestfallen and believed all of his work on the theory had been for naught until he remembered that he had told Asa Gray about the theory several years earlier. So he owed an enormous debt of gratitude to Gray, and to show that gratitude he sent Gray the first copy of "Origin of Species" to these shores, and Gray read it enthusiastically and takes it upon himself to become the American proselytizer of Darwin's theory, and in three essays in the summer of 1860, he argues for the legitimacy and the credibility of Darwin's work in the pages of "Atlantic Monthly."

PALMER: But another very famous Harvard luminary was very much not convinced about Darwin. Tell me about that. It’s Louis Agassiz.

FULLER: Louis Agassiz was the Professor of Zoology at Harvard College, and far and away the most well-known popular scientist of his day, and the foremost opponent of Darwinian theory in America in 1860. And the reason that he was so vehemently opposed to Darwin's theory is because he was also the strongest advocate for the theory of special and separate creation that I discussed earlier. He was a proponent that blacks and whites and other races had been created separately, just as he believed Monarch butterflies were created in specific environments. Darwin's theory threatened his own belief in special creation, and so he fought back vigorously.

Depiction of the interior of the engine house during John Brown's raid, published in Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper November 5th, 1859. (Photo: Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper, v. 8, no. 205 (1859 Nov. 5), p. 359. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

PALMER: Now, it arrived quite soon in Concord, which was the home of Henry David Thoreau, among others, and there was a huge intellectual ferment going on anyway there. What was their reception of this book?

FULLER: So, it was mixed as Darwin's reception has been mixed to this very day. Ralph Waldo Emerson read it in a somewhat shallow way and saw the idea of evolution as progressive and developing always to something better and more majestic, and so he read Darwin as essentially a confirmation of his own theories of transcendental progress. Bronson Alcott, who was even arguably a greater idealist than Emerson, rejected Darwin outright, and his argument was that any theory that began with material processes and the physical was starting at the wrong end, that one had to begin with the divine spirit and work one's way down.

Abraham Lincoln, on June 3, 1860, two weeks after Lincoln’s nomination. (Photo: Alexander Hessler, Springfield, IL, Wikimedia Commons)

Only Henry David Thoreau of the transcendentalist cohort really grappled with Darwin's theory, in a way that was both supple, tough-minded, and ultimately, I think, synthetic. That is to say, he was able to combine his transcendental beliefs with Darwin’s materialism in a new kind of approach to nature.

PALMER: Were Darwin's theories actually widely accepted in the north? I mean, you've spoken about Agassiz being very opposed, but among the general population did they go down well?

FULLER: They were pretty quickly absorbed into the culture. We may not believe or think that, given the enormous difficulty the theory has in contemporary America, but by the late 1860s, less than a decade after the book arrived, Darwin's theories were taught in all colleges as credible theory.

PALMER: But you hardly mention the south. I mean, at this time, did these theories get down to the south, and how were they received there?

FULLER: Finding out how Darwin's theories were received in the south is a little trickier than in the north where we have access to diaries and journals of all of these major thinkers, but the reviews of the book, which appeared first in New England, almost immediately appeared in places like Richmond, Virginia, and New Orleans, and without the kind of resistance that you might think. They were usually reviews that reported upon this interesting new theory that proposed to explain the creation of new species.

Author Randall Fuller. (Photo: Erik Campos)

PALMER: As I read this book, there seems to be more than a few parallels between what was happening then and what’s happening now. Do you think it has lessons for us?

FULLER: Well, I certainly think it does and particularly I think there's a cautionary tale about bending evidence or facts to a preconceived narrative or ideology, and this is why Thoreau is sort of a hero for me in the book because he tries not to do that to the best of his abilities.

CURWOOD: Randall Fuller’s new history is “The Book that Changed America.” He spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Related links:

- “The Book That Changed America”

- About Randall Fuller

[MUSIC: Lawrence Blatt, “Black Rock Beach” on The Color of Sunshine, LMB Music]

Beyond the Headlines

Kemper Coal Gasification Plant. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Finally, let’s look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is with Environmental Health News, that’s e-h-n dot org and DailyClimate dot org and he’s on the line now from Atlanta - hi Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hey Steve, would you mind if we started with a little good news this week?

CURWOOD: I’m ready for that anytime. Go ahead.

DYKSTRA: Well, Germany's on a pace to get 35% of its electricity from renewables this year.

CURWOOD: Well, that's impressive. There’s not so much push in Washington for that right now.

DYKSTRA: Or for science either. The lights are out in President Trump's Science Office.

CURWOOD: Oh, what’s going on?

DYKSTRA: Well, there’s no boss for science in the Whitehouse, and no staff, apparently, either. But as news like the colorful Presidential tweets capture headlines, episodes like Mr. Trump's abandonment of the Paris Climate accords became background noise, or as the President likes to say, "fake news."

CURWOOD: Hmmm, well, OK, so what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: So let's move on to one that's close to home for me here in Georgia. Southern Company, the big utility conglomerate here in Dixie, bailed on a $7 billion so-called "clean coal" project in Mississippi.

CURWOOD: I guess you could say these are dark days for the concept of clean coal.

Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Yeah they sure are. The Kemper plant was the nation's most ambitious clean coal experiment. With the failure of Kemper, as many predicted, "clean coal" is pretty much dead.

It’s not been a good week for Southern Company, particularly as its nuclear arm, along with Georgia Power has invested -- bigly -- in the Plant Vogtle nuclear project’s two reactors.

Georgia Power and Southern Company said they expect to take over the formal management there in late July since a key contractor, Westinghouse, has filed for bankruptcy.

CURWOOD: So, what’s going wrong?

DYKSTRA: Well, the project is at least two years behind schedule and three billion dollars over budget.

CURWOOD: That’s a piece of change. What about history this week. What can you tell us?

DYKSTRA: Well, let’s stick with the nukes because this spring marked 40 years since the peak of the anti-nuclear power movement in the US.

One thousand, four hundred fourteen people got arrested for occupying the construction site of the Seabrook nuke plant in New Hampshire.

CURWOOD: Yeah, but in spite of those protests, one of the Seabrook nuke reactors got built.

DYKSTRA: Yes, but after protests like Seabrook and accidents like Three Mile Island and Chernobyl, Wall Street's cold feet on nukes never really warmed up.

The anti-nuclear movement goes back for decades in the United States. (Photo: Mac, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: And I guess all these problems there in Georgia aren’t going to reverse the trend.

DYKSTRA: I seriously doubt it Steve.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, e-h-n dot org and DailyClimate dot org. Thanks Peter, we'll talk again soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at our website, LOE dot org.

Related links:

- National Geographic | Germany and renewable energy

- The Boston Globe | “40 years after the Seabrook Protests”

- CNN | “No Room for Science in Trump”

[SYMPHONY OF CALLING FROGS]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week, listening to the symphony in a southern swamp.

[SOUNDS OF MANY FROGS]

CURWOOD A variety of frogs are singing – there are the nasal notes of Green Tree frogs, and the clicking tones of cricket frogs…

[SOUNDS OF PIG FROGS GRUNTING, CRICKET FROGS CLICKING]

CURWOOD Sometimes the deep tones of a bullfrog provide the bass, and some pig frogs grunt….

[SOUNDS OF BULL FROG AND LEOPARD FROGS]

CURWOOD And Leopard frogs add their chatters as percussion.

Lang Elliott recorded these noisy frogs in Apalachicola National Forest for his CD Voices of the Swamp.

[MUSIC: Jacqueline Schwab, “The Minstrel Boy” on Baseball A Film By Ken Burns - Original Soundtrack Recording, written byThomas Moore/arr.Schwab, Nonesuch]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Matt Hoisch, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Alex Metzger, Helen Palmer, Rebecca Riedelmeier, Adelaide Chen, Olivia Reardon and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth