Wee Turtles Graduate

Air Date: Week of July 28, 2017

Benji Miranda checks a turtle trap at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge on a field trip (Photo: Don Lyman)

After raising Blanding’s turtle hatchlings all year, it’s time for a class of fifth-graders to send their charges back to the wild to make it on their own. As we complete our series covering a program that gives threatened Blanding’s turtles a head start in life, Living on Earth’s Don Lyman follows the hatchlings into the classroom, and on to Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Well, one of the babies from Turtle 2028’s nest was christened “Tsunami” by its adoptive elementary school students. And in February of 2017, Living on Earth’s Don Lyman followed the little turtle into a classroom.

LYMAN: On a clear but cold February day, snow from a recent storm blanketed the outdoor basketball courts at the Carlisle School. But inside the tank where two young turtles lived, it was a balmy 80 degrees or so, and the classroom itself teemed with excitement.

One of the hatchlings that Chris Denaro’s class cared for at the Carlisle School during the 2016-2017 academic year. (Photo: Don Lyman)

[KIDS TALKING; TEACHER CLAPS FOR ATTENTION]

LYMAN: I found myself among perhaps the only people with more questions than journalists: fifth graders.

SCHULER: You guys have so much curiosity about turtles! This is amazing, yes.

LYMAN: Chris Denaro’s students grilled Emilie Schuler, the Director of Programs and Operations at Grassroots Wildlife Conservation, about everything from how many turtles are left in the world, to potential hazards the littlest ones face.

KID: Do people step on those turtles?

SCHULER: They might. Yeah I’m sure and a small turtle like this, it probably could get crushed by a person stepping on it.

LYMAN: The kids were in the midst of a yearlong project to take care of two baby turtles, to give the hatchlings a head start in life, so they’d have a much better chance of surviving to adulthood and boosting the threatened species’ numbers when they’re released in the spring. One of those babies was from Turtle 2028, the mother we followed starting in July of 2016. By now the kids were pros at feeding the turtles, giving them fresh water and weighing them, but they still had lots to learn about some amazing things the hatchlings – which they’d named Tsunami and Squirtle -- could do.

SCHULER: Okay, so today we’re gonna be learning all about your turtles and some really cool superpowers that your turtles have. Some things that turtles can do that humans can’t do. Did you guys know that turtles have superpowers?

KIDS: No…. Yes…

LYMAN: During the harsh New England winters, those superpowers are essential for survival. Tsunami and Squirtle had it easy in their warm and artificially-sunny tank, but the kids who cared for them always had to bundle up during recess. We humans have to keep our bodies near a toasty 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. If a human’s body temperature drops below that by even a few degrees, we can quickly succumb to hypothermia. But Blanding’s turtles can chill to just above freezing.

SCHULER: Can a turtle’s body, Is it okay for a turtle for its body to be 33 degrees?

KIDS: Yeah… No…

SCHULER: Yeah! Right, that’s the really cool thing. It’s like kind of a superpower of turtles and of reptiles that they can have their body so, so, so cold. They can drop their body temperature like that and still be fine.

LYMAN: In order to still be okay with such a low body temperature, Blanding’s turtles have to slow down, waaaay down.

SCHULER: They’ve measured turtles that are this cold, and their heart was beating only one time every ten minutes.

KIDS: Whoa!!!!!

LYMAN: It sounds incredible, but that’s normal for turtles in winter, part of a nifty adaptation that allows them to slow their metabolism way down. And when that happens, they need a lot less oxygen. They still need some and can absorb small amounts through their skin. And they have another trick up their shell.

SCHULER: So turtles have the ability to hold their breath for a really, really, really long time.

LYMAN: Like – for months.

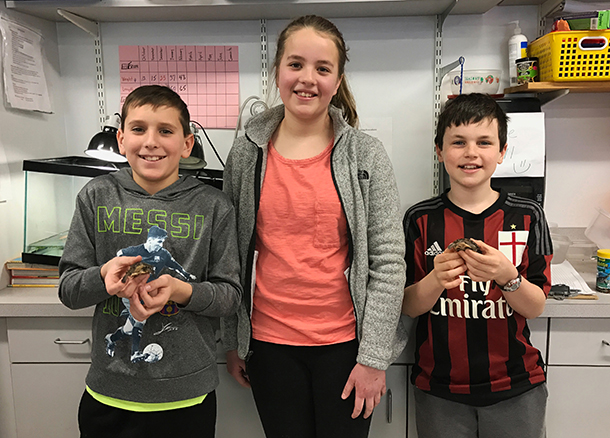

Ian, Sienna, and Owen with their class’s two Blanding’s turtle hatchlings. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

SCHULER: Scientists have even done studies where they’ve purposely, they’ve put turtles in water where they’ve bubbled out all the oxygen. Those turtles stayed under the water super-chilled for five months.

KIDS: What?!!? Oh my!

SCHULER: So those turtles were holding their breath for five months. Is that a cool superpower or what?!

KID: That’s cool.

LYMAN: But a metabolism that’s barely detectable is not so great for growing up big and strong.

SCHULER: So. Your Blanding’s turtle cousins that are outside, right – Tsunami has cousins that are not lucky enough to be in classrooms today are outside. Maybe, right, in the swamps of Great Meadows under the ice right now. And they are gonna be surviving over the winter. Pretty cool stuff that they can do that. But those cousins that are out in the winter right now, are they gonna be growing like Tsunami?

KIDS: No.

SCHULER: No. So even if they were the same age as Tsunami, come April or May, when it starts getting warmer and they come out, what’s the size difference gonna be between Tsunami and their cousins?

LYMAN: The answer: around 7 or 8 times the weight! That’s the main reason why the head start program is proving so valuable for boosting Blanding’s turtle population numbers. In just eight months, the kids make the baby turtles look like four-year olds, so they’re less attractive to predators like raccoons, herons, and bullfrogs, and much more likely to make it out in the wild.

[SOUND OF SCHOOL BUS PARKING]

DENARO: Hi, how are you? Nice to see you again.

LYMAN: A few months later, on a sunny June morning, it’s time for Tsunami and Squirtle to set off on their own.

[SOUNDS OF CLASS CHATTERING]

LYMAN: We meet up with the Carlisle School fifth graders at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge in Concord, Massachusetts, where Bryan Windmiller, the Executive Director of Grassroots Wildlife Conservation, is back in his waders with an assistant.

WINDMILLER: Good morning, guys.

STUDENTS: Good morning.

WINDMILLER: So, I’ve met you guy. I’m Bryan Windmiller. This is Benji Miranda, who works with me. We’ve got a beautiful morning to go check out the habitat where your turtles are going to be living.

[FOOTSTEPS ON PATH, RED-WINGED BLACKBIRD SONG]

LYMAN: The class starts down the tree-lined path that leads to the ponds at Great Meadows. It’s a pleasant spot. Beyond the trees cattails wave in a light breeze over the deep-blue ponds. Butterflies and red-winged blackbirds flit through the air, and occasionally you might see a Great Blue Heron take to the sky. Yet while it looks natural, it’s very much not.

WINDMILLER: All around here we have a real mix of plants & animals that are both from here, that started out here so they’re native. And there are also lots of species that got here only recently, because people, whether on purpose or not, have brought them. These beautiful smelling roses, right? I’m getting all the perfume from these guys. This is an Asian rose. It’s called Multiflora rose. So it’s only here because people brought it here. They thought it looked good, the blossoms smell really good, and now it’s all over the place.

LYMAN: Invasive species like purple loosestrife, Asian water chestnut, American lotus, and European carp have affected the makeup of flora and fauna here. And even the ponds themselves are not natural.

WINDMILLER: This whole place, as we walk along, you’ll see there are two big ponds that extend on either side. And this place is called Great Meadows, right? It’s not called Great Ponds. 80 years ago these were kind of scrubby meadows where people earlier in history from Concord used to graze their cows.

LYMAN: Then a man named Samuel Hoar, who owned 250 acres of the land known as “Great Meadows”, decided to build low earthen dams, or dikes, to hold water within the meadows, so that he could hunt the waterfowl that would be attracted to the ponds. But the change wrought by a private landowner who wanted to hunt ended up having a positive impact for some species.

WINDMILLER: We all know about all different ways in which people can affect the environment in ways that makes it harder for wild animals to live there. But in all kinds of ways, too, people can change the environment to help different kinds of wild animals. Whether it’s on purpose – Samuel wanted there to be more ducks so he could hunt them – but Samuel also made this better Blanding’s turtle habitat.

LYMAN: The turtles were here before the artificial ponds, and their population got a nice boost from the extra habitat. Then, as residential developments went up near Great Meadows in the latter half of the 20th century, and the turtles lost nesting habitat and fell victim to automobile traffic, their numbers dropped again. They’re now a threatened species in Massachusetts, so Grassroots Wildlife Conservation is working to get the adult population back to 200 from the 50 or so Blanding’s Turtles that live at Great Meadows now.

Students walk along the path dividing the man-made ponds at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge before releasing their turtles into the ponds. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

[FOOTSTEPS ON GRAVEL PATH]

LYMAN: On the straight-as-an-arrow dike that divides the two man-made ponds, the group stops a couple times to check turtle traps Bryan and Benji had set earlier that morning.

[SPLASHING SOUNDS]

MIRANDA: So these big ones are the ones we usually try and find the adult Blanding’s turtles in.

LYMAN: Neither trap has any Blanding’s turtles, but there are several pretty painted turtles.

WINDMILLER: Anybody wanna hold this guy? So if you hold this guy, just remember, right? He’s a wild turtle. So, if you put your finger right in front of his face, what might he do?

KIDS: Bite it.

WINDMILLER: Bite you on the finger. So don’t put any part of your anatomy right in front of his face.

LYMAN: Soon it’s time to head back down the path to the parking lot. There’s a big metal observation tower at one end, where birders and other nature enthusiasts can peer down across the ponds to spot the many wildlife species that call this place home. Bryan gathers the group at its base to record some final data points about Tsunami and Squirtle before they’re released, and to deepen the notches in their shells that will help identify them when they’re recaptured, perhaps years later.

WINDMILLER: All right, what have we got?

KID: Seventy-four…

WINDMILLER: Seventy-four point zero. Thank you Squirtle. Okay, so, who’s got the data sheet? Awesome. So he’s now, right, seven times heavier than he was when you got him, and when he hatched he would have probably been even a little less than that, right? So probably eight times heavier now. Which is a huge difference. And when they get to be fully adult, right? In their late teens or early twenties, they get to be…A big Blanding’s turtle around here will be around 1,800 grams. So you guys need to get back, and Tsunami and Squirtle need to get going. So, if you want to go up on the tower…And you can array yourselves, some of you on the top, some of you on the stairs.

[FOOTSTEPS ON TOWER STAIRS]

LYMAN: From the tower they watch as Bryan and Benji wade between cattails, to a nice shallow spot in the ponds.

KID 1: Nooooo they’re leaving! Guys, the turtles are leaving .

KID 2: They’re going away! .

KID 3: It’s their first time in the water other than their tank.

WINDMILLER: So, first we’ll let Squirtle go. Do you guys wanna say goodbye to Squirtle?

KIDS: Bye, Squirtle!

WINDMILLER: So now we’ll let Tsunami go. You guys can say goodbye to Tsunami.

KIDS: Bye Tsunami!

LYMAN: One kid, Owen, isn’t quite sure how to feel about saying goodbye.

OWEN: I liked watching them grow, ‘cause it made me -- It just made me happy to see them getting bigger and that they’d be released. I mean I’m happy that they can go, but I’m sad we can’t take care of them anymore because they’re so cute. So it’s like melancholy.

Bryan Windmiller and Benji Miranda wade between cattails at Great Meadows to release “Tsunami” and “Squirtle”. (Photo: Don Lyman)

LYMAN: What do you wish for the turtles?

OWEN: I want them to get really large and die naturally, not from a predator. Even though that is kind of naturally. But still.

LYMAN: Judging by the high survival rates of turtles that have gone through the head start program in years past, Owen may very well get his wish.

WINDMILLER: Actually, what’s really cool is we just found a turtle who is from 2028, who was released last year. The previous class found him right about here, walking across the path.

LYMAN: And a few days later, as night fell, exactly a year and one day after number 2028 laid the eggs that would include Tsunami, Bryan reported that she was just finishing up her nest in someone’s front yard, across the street from where she laid her eggs last year. The eggs looked normal. There were eight of them. And since Turtle 2028 had chosen a recently-delivered mulch pile for her nest, Bryan and his team gently moved them to a safer spot in the earth a few feet away. All summer long they’ll incubate in the warmth of the nest. And then, one day in autumn, these young Blanding’s turtles will poke through their shells, crawl up through the earth, and go to school.

For Living on Earth, I’m Don Lyman in Concord, Massachusetts.

Links

Grassroots Wildlife Conservation’s Blanding’s Turtle Monitoring and Headstarting project

More about the Blanding’s turtle from the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife

Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, the new home of “Tsunami” and “Squirtle”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth