July 28, 2017

Air Date: July 28, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

California Climate Loss & Damage Lawsuits

View the page for this story

Two counties and a city in California are suing more than 30 major oil and gas companies for losses and damages expected from global warming. Michael Burger, a law professor at Columbia University, tells Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood why these lawsuits could change the way lawyers approach climate litigation. (07:58)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In Greenland, gyrfalcons inhabit ancient nests that in some cases contain 2,500 years of accumulated guano! But increasingly, as Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood discuss, Greenland’s gyrfalcons are being pushed out of these nests by peregrine falcons, which feel more welcome than ever in Greenland thanks to warming in the Arctic. Also, Volkswagen may build a factory in Rwanda to manufacture low-emission and electric vehicles; and we mark the 59th anniversary since a U.S. naval submarine began collecting data on ice thickness during the Cold War. (03:32)

Wee Turtles Go to School

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

For Blanding’s turtles, which are threatened in Massachusetts, a program that pairs vulnerable hatchlings with schoolchildren is boosting their numbers. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering describes the beginning of the ‘head start ‘cycle, when a new mother, Turtle 2028, laid her eggs in June of 2016, and follows her hatchlings as they emerge from the nest months later. (05:34)

Wee Turtles Graduate

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

After raising Blanding’s turtle hatchlings all year, it’s time for a class of fifth-graders to send their charges back to the wild to make it on their own. As we complete our series covering a program that gives threatened Blanding’s turtles a head start in life, Living on Earth’s Don Lyman follows the hatchlings into the classroom, and on to Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge. (12:37)

White Man’s Game

View the page for this story

Western environmental philanthropy in Africa has often focused on habitat and species conservation. Journalist Stephanie Hanes writes in her new book, White Man’s Game: Saving Animals, Rebuilding Eden, and Other Myths of Conservation in Africa, these well-intended projects can fail if they ignore local culture and beliefs. Using Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique as an example, Hanes and host Steve Curwood discuss the challenge of cross-cultural conservation endeavors. (16:42)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Michael Burger, Peter Dykstra, Stephanie Hanes

REPORTERS: Jenni Doering, Don Lyman

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood.

A California city and two counties are taking big oil and gas companies to court for selling global warming products that are raising sea level and threatening coastal properties.

BURGER: Basically what the plaintiffs here are saying is that the fossil fuel industry knew that this was going to cause climate change. They hid that fact as much as they could. They lied about it. They paid others to lie about it, and as a consequence they should pay for the damages.

CURWOOD: And school children who raised threatened turtles all year send their charges off on their own.

OWEN: I’m happy that they can go, but I’m sad that we can’t take care of them anymore, because they’re so cute. So, it’s like melancholy. I want them to get really large and die naturally, not from a predator, even though that is kind of naturally.

CURWOOD: How a head-start program gives baby turtles a leg up. That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

California Climate Loss & Damage Lawsuits

Pigeon Point Lighthouse in San Mateo County is one of the most iconic on the California Coast. (Photo: Frank Schulenburg, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, This is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Investigations continue into whether ExxonMobil allegedly misled investors by failing to tell what their own scientists had found out about global warming continue, and now Exxon and other fossil fuel titans are being challenged on another legal front. Marin and San Mateo counties and the City of Imperial Beach in California are taking 37 companies and trade groups to court. They claim the defendants knew about the threats posed by burning fossil fuels years ago. And now, as seas rise on the California coast, and adaptation costs loom, these communities want them to pay damages.

For a discussion about what this newest string of lawsuits means for the legal war against climate disruption we turn to Columbia law professor Michael Burger. Welcome back to Living on Earth.

BURGER: Thanks, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, what's being sought in these lawsuits?

BURGER: What these local governments are claiming is that these fuel companies have known for many years about the consequences of the use of their fossil fuel products, particularly that use of these products would contribute to climate change and cause any number of damages, including damages resulting from sea level rise, and so they are seeking to have these companies pay for a number of different types of costs, including the costs of adaptation to climate impacts from sea level rise, as well as costs associated even with studying the issue, planning to address the issue, development of adaptation plans, and then implementation of those plans as well.

CURWOOD: So, be more specific for me about the kinds of climate impacts that the citizens of these counties have already been affected by and possible costs associated with them.

BURGER: The basic claim here is that, as sea levels rise, coastal property is lost -- It is literally inundated -- That homes are at increased risk of severe storms and flooding from extreme precipitation events, and that critical infrastructure has also, has already been impacted and is at risk of increased impacts. So, we're talking about roads, bridges, hospitals, and all kinds of infrastructure that make up the communities within these counties and city.

CURWOOD: Now, at the heart of these claims is the idea that companies are infringing on the public nuisance doctrine. What is nuisance law, and how might these companies be breaking these laws, or not?

BURGER: Basically, the idea of the public nuisance doctrine is that there are certain resources and rights to health and well-being that are held in common by the public, and that private actors can infringe upon those rights and create a nuisance that is not just a nuisance to you or me as a homeowner or a property owner or a person with our own bodies, but that, in fact, they're causing harms to goods that are possessed by all of the members of the state.

Flooding in Larkspur in Marin County, a plaintiff in a climate loss and damage lawsuit three California localities have brought against a number of fossil fuel companies. (Photo: Jesse Wagstaff, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What precedent exists for these cases?

BURGER: So, this is not the first time that we've seen common law claims brought around climate change. Back in 2005, a number of states and cities as well as some environmental organizations and land trusts claimed that five power companies, the five largest power companies in the United States, should be held liable for the public nuisance of climate change. And that case, which was known as Connecticut versus American Electric Power, eventually made its way all the way up to Supreme Court, where the Supreme Court said that the common law claims were preempted, that they were displaced by the Clean Air Act, that since Congress had acted on this already, there was no further room for the courts to act.

But importantly, what that case was talking about was a federal common law claim of public nuisance. These lawsuits allege state common law claims, and we have not yet had any final decision or really any court address the issue of whether state common law claims can survive.

CURWOOD: Now, some are comparing these lawsuits to litigation that took down the tobacco industry in the 1990s. How accurate might that comparison be?

BURGER: Well, there certainly are similarities. You know, I guess I'll start off actually by talking about what the key differences is.

In the tobacco case, you had companies that were manufacturing a product that was directly consumed by an individual and that direct consumption led to cancer and other health problems. Here, you have fossil fuel companies who are -- In this lawsuit, they're largely extraction and production companies, so they're pulling the fossil fuels out of the ground and preparing them for the market and sending them. But eventually, there are other consumers who are combusting those fossil fuels, and that includes you and me, and so you basically have a much longer chain of causation between what these companies have done and the harms that are being claimed and what the tobacco companies did and the harms that were claimed in those cases.

Now, that being said, there's a very key similarity here, which is, like the tobacco litigation in the 1990s, these lawsuits rely on a long history of corporate knowledge and obfuscation to make their claims. Basically, what the plaintiffs here are saying -- What these counties and cities are saying -- is that the fossil fuel industry knew that this was going to cause climate change. They hid that fact as much as they could. They lied about it. They paid others to lie about it, and they've been holding on as long as they can to their existing business models, and as a consequence they should pay for the damages.

CURWOOD: How does that assertion work under common law? If you say that somebody is making and selling a product that they know is bad, is going to cause harm, and not telling the public about those possible consequences, how vulnerable are they under this standard of common law?

BURGER: I mean, it remains to be seen. It's quite possible that these cases will be dismissed immediately for any number of different reasons. The courts could find that this is a political question, that climate change is really a political question that ought to be resolved by Congress and the Executive Branch and that courts shouldn't be deciding these types of cases. They might say that it's just impossible ultimately to prove causation. They might say that federal laws have preempted. These companies were extracting fossil fuels under license from the federal government when they were doing it within the United States and in most, if not all, circumstances with permits and licenses from other governments, foreign governments, when they were doing it abroad. So, it is certainly feasible that these cases will disappear fairly quickly.

Michael Burger is the Executive Director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. (Photo: Columbia University)

That said, we're in a much different place than we were five years ago. The knowledge about how long these companies have known about climate change, what they did to obscure the public debate about climate change, is much more well-grounded than it was even back then. In addition, the science is much more advanced, and the science of attribution, in particular, is much more advanced. So, there are a number of different methodologies that scientists and experts can now rely on to say, well, we can attribute a certain quantity of greenhouse gas emissions to these particular actors. We can say these fossil fuel companies are ultimately responsible for this quantity of emissions. They can also say that this quantity of emissions has had this much of an impact on global warming and global climate change, and then, they can even say that this amount of global warming and global climate change has contributed X amount to the increased risk of sea level rise impacts in these particular communities. None of those are a slam-dunk, but the plaintiffs are in a much better place to rely on the existing science to support their claims.

CURWOOD: I would imagine that if one iota of responsibility is found by the courts there, that even if it's half a percent of the damages, those numbers are huge.

BURGER: Ultimately, they can be huge, especially if we start to see these types of lawsuits pop up, not just in these particular communities in California but other communities in California, and other communities all around the United States.

You know, I think that this lawsuit, these lawsuits are of a type of lawsuit that those of us in the field have been waiting a long time for. We've been wondering when these public nuisance state common law claims would be brought. And here they are.

CURWOOD: Michael Burger is Executive Director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University. Thanks so much for taking the time with us, Professor.

BURGER: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- The Washington Post: “This could be the next big strategy for suing over climate change.”

- (San Jose) Mercury News: Two Bay Area counties sue 37 fossil fuel companies over sea-rise.

- Michael Burger Faculty Profile

Beyond the Headlines

An electric Volkswagen e-Up vehicle at a charging station (Photo: Norsk Elbilforening, Wikimedia Commons CC)

CURWOOD: Time now for a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org, and joins us now on the line from Atlanta. Hi, Peter, what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. Let's start out with a rare opportunity to put Rachel Carson, William Shakespeare, and guano as old as the Roman Empire in the same story.

CURWOOD: By guano, we mean bird droppings, right? Good luck on this one.

DYKSTRA: Well, the author part is easy. Shakespeare was said to be a big fan of the ancient sport of falconry. Rachel Carson's writing on the pesticide DDT is largely credited with saving bird species, including the peregrine falcon here in North America.

CURWOOD: Hmm, OK. Well, their writings certainly had wings, one might say; but what about this ancient guano?

DYKSTRA: Right, well gyrfalcons are big, surprisingly laid-back birds of prey, and some of them summer in Greenland. They tend to appropriate other bird species' nests, including some that are 2,500 years old. And after two and a half millennia of use, a bird nest tends to be made mostly of petrified bird poop.

CURWOOD: With a laid-back gyrfalcon as a nest-squatter, huh?

Peregrine falcons, driven by a warming climate, are moving further north in Greenland, where they compete with native gyrfalcons for nests. (Photo: Georges Lignier, Wikimedia Commons CC)

DYKSTRA: Correct. But some peregrine falcons also summer in Greenland, in increasing numbers thanks to the DDT ban, and warming is the prime suspect in their recently showing up much farther to the north in Greenland, where they have no problem evicting the gyrfalcons from their prized, purloined poop palaces. Researchers have been following this unlikely drama for years, knowing that this 2,500 year-old guano nest just ain't big enough for the two falcons.

CURWOOD: Well, I'm sure you'll keep us posted.

DYKSTRA: It's what I live for.

CURWOOD: All right, what's next?

DYKSTRA: In what may be part of a continuing penance for a major emissions cheating scandal, the Rwanda Development Board says Volkswagen may be looking at building a factory for low-emission and electric vehicles in the tiny African nation.

CURWOOD: Hmm, so what is this? Green guilt, or is it a good business move?

DYKSTRA: Well, could be both. Rwanda and its capital city, Kigali, suffer from pollution problems all too common in the developing world. And virtually all of Africa has potential to grow its middle class like China and India have done in recent years.

CURWOOD: So VW may be turning environmental disgrace into environmental progress. Hey, what do you have for us this week from the environmental history vault?

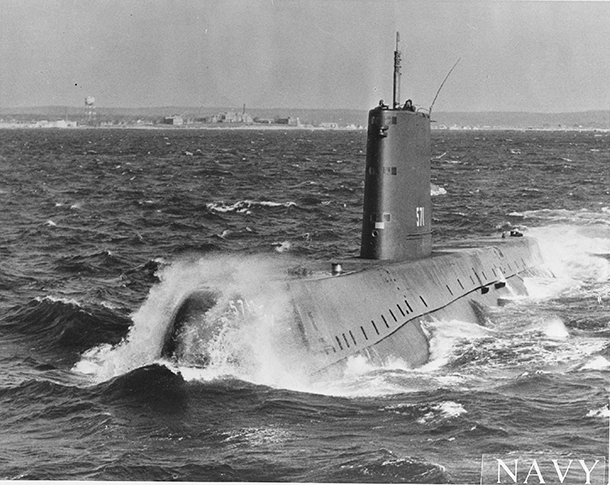

DYKSTRA: Well, 59 years ago this week, the nuclear sub USS Nautilus began its first-ever trip under the ice of the North Pole. Decades later, when the Cold War finally melted away, the US and Russian navies declassified their years of data on how thick the ice was up there.

Data collected by the USS Nautilus dating from the Cold War is giving scientists a record of the change in Arctic ice thickness over the decades. (Photo: US Navy, Wikimedia Commons CC)

CURWOOD: I'm afraid I may already know the answer to this, Peter, but why were the Americans and Soviets so interested in Arctic ice thickness back then?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, you probably do know the answer. The Americans and the Russians were engaged in preparation for thermonuclear war, and those submarines under the North Pole ice might be needed to poke through the ice and fire their missiles. So one little legacy of nuclear madness is that we have a 59-year-long record of the decline of Arctic ice thickness thanks to a vestige of the Cold War.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health new -- That’s ehn.org – and DailyClimate.org. Thanks, Peter. Talk to you again next time!

DYKSTRA: OK, Steve. Thanks a lot. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org

Related links:

- The Atlantic | The Battle Over 2,500-Year-Old Bird Nests Made of Poop

- BBC: 2,500-year-old bird's nest found

- The (Rwandan) New Times | “Volkswagen to assemble electric cars in Rwanda” http://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/216593/

- African Review:

- History of the USS Nautilus

[MUSIC: Nina Simone, “Consummation” on Silk & Soul, RCA Victor]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...time to send wee Blanding’s turtles out on their own. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Pinetop Perkins & Jimmy Rogers, “Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie” on Pinetop Perkins & Jimmy Rogers, published by Little Mike and the Tornadoes, littlemikeandthetornadoes.com]

Wee Turtles Go to School

A baby Blanding’s turtle takes its first swim (Photo: Don Lyman)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

You might know Head Start as a government program to help give children from vulnerable low-income families a better shot at doing well in school and in life. But “head start” programs aren’t just for kids, as Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering reports from Concord, Massachusetts.

[SOUNDS OF BIRDS SINGING ON A SUMMER DAY]

DOERING: The Blanding’s turtle is a threatened species in the bay state, and baby Blanding’s face tough odds for survival.

WINDMILLER: They’d have maybe a 1 in 80, 1 in 100 chance of living to be adults.

DOERING: That’s Bryan Windmiller, the Executive Director of Grassroots Wildlife Conservation. The nonprofit sends the vulnerable hatchlings to schools, so kids can raise them.

WINDMILLER: We give them at least a forty-fold increase in their chances of surviving to adulthood.

DOERING: That’s because little turtles are an easy snack for predators. Their tiny, half-dollar-sized shells are actually folded inside the egg and Bryan Windmiller says they’re still soft for months after they hatch.

WINDMILLER: So we take them when they’re at that real vulnerable stage, and we give them to schools, and they raise the turtles for nine months, take care of them all winter, keep them warm, feed the turtles as much as they want. And in that environment, they grow super quick, so when we let ‘em go, they’re on average about 12 times, sometimes 15 or 20 times, heavier; they’ve got a much bigger shell, really strong shell; they don’t have to worry about chipmunks, they don’t have to worry about bullfrogs, they don’t have to worry about blue jays, and garter snakes.

Covering the nest with a mesh screen protects it from predators like skunks and raccoons (Photo: Don Lyman)

DOERING: But natural predators aren’t the only hazards that threaten the turtle hatchlings.

WINDMILLER: Sometimes they’d be destroyed completely unintentionally by people, because sometimes they nest in farm fields that would get plowed, or they nest in people’s perennial beds that might get turned over and stuff like that.

DOERING: And because of these threats, the Blanding’s turtle population at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge in Concord has been declining for decades.

WINDMILLER: There are only about 50 adult Blanding’s turtles here at Great Meadows, spread among a bunch of wetlands. And that’s down from probably 150 in the early 1970s. So our overall goal here is to help restore this population.

DOERING: To kickstart their recovery, Bryan and his team track female turtles and guard their eggs while they incubate during the summer.

[SOUNDS OF A SUMMER EVENING]

DOERING: Late on a warm evening in June 2016, I huddled with Bryan and his team around the newly-dug nest of Turtle 2028.

WINDMILLER: There we go. Nice.

DOERING: That’s pretty cool.

The bright yellow throat of the Blanding’s turtle can help biologists recognize the species, which is threatened in Massachusetts, from a distance (Photo: Emilie Schuler / Grassroots Wildlife Conservation

WINDMILLER: So we can just expose the top three eggs of her nest. Actually you can see at least four. They’re about, uh, four inches deep. We’re very glad, she started about 7:30. It’s now about 11:30. Looks like she pretty recently finished, so now we’ll just cover it back up with dirt, like she did, like Mom did, and put a screen over it so raccoons and skunks can’t get it.

[SOUNDS OF METAL RUSTLING]

WINDMILLER: And then we just wait until late August or September, when the babies come out.

DOERING: We waited all summer of 2016 for those baby turtles to hatch. That year New England wilted in a severe drought, and in September the turtles hadn’t yet hatched. Bryan Windmiller was concerned that they might have perished, so he went to check the nest with Program Coordinator Emilie Schuler. They removed the protective metal screen.

[SOUNDS OF METAL RUSTLING]

WINDMILLER: Okay, you gonna go for it, Emilie?

SCHULER: Okay.

[DIGGING SOUNDS]

SCHULER: Oh, what’s this – Oh, that’s the—

WINDMILLER: Temperature logger.

SCHULER: Temperature logger. Okay, well, we’ve got that.

WINDMILLER: So this records the temperature every hour. It will allow us to predict with reasonable accuracy whether the hatchlings are boys or girls.

[DIGGING SOUNDS]

SCHULER: So I think I’m seeing our first little friend here. There’s something, some egg and some movement.

WINDMILLER: Oh! That’s looking good.

SCHULER: There’s movement. There he is.

WINDMILLER: It’s a little one.

SCHULER: Awww.

Bryan gently digs in the mulch in front of a Concord home to uncover the first few eggs in turtle 2028’s nest. (Photo: Don Lyman)

WINDMILLER: Yeah, wonderful. Looks like that one too has been hatched for a little bit, just been sitting there.

So Emilie just dug up – Here’s an egg, that, you can feel, it’s got a formed embryo inside of it. But I’m suspecting that it’s not viable anymore. This also, this nest may be pretty small because this was a first-time mom, and first-time moms often lay pretty few eggs compared to the normal average of about ten.

DOERING: All in all, Turtle 2028 laid four eggs in her nest, a low number probably due to the searing drought in 2016.

WINDMILLER: That’s less than half the size of a typical Blanding’s turtle clutch. And two out of the four survived, which is also low. The good news is, we’ve got a baby who looks healthy. And this is the second one from this nest. And we have a lot of fourth graders in Concord who are really looking forward to meeting their turtles.

DOERING: For Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

Related links:

- Grassroots Wildlife Conservation’s Blanding’s Turtle Monitoring and ‘head starting’ project

- More about the Blanding’s turtle from the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife

- About Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge

- GRASSROOTS WILDLIFE FOUNDATION: Watch a Blanding's turtle laying eggs

Wee Turtles Graduate

Benji Miranda checks a turtle trap at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge on a field trip (Photo: Don Lyman)

CURWOOD: Well, one of the babies from Turtle 2028’s nest was christened “Tsunami” by its adoptive elementary school students. And in February of 2017, Living on Earth’s Don Lyman followed the little turtle into a classroom.

LYMAN: On a clear but cold February day, snow from a recent storm blanketed the outdoor basketball courts at the Carlisle School. But inside the tank where two young turtles lived, it was a balmy 80 degrees or so, and the classroom itself teemed with excitement.

One of the hatchlings that Chris Denaro’s class cared for at the Carlisle School during the 2016-2017 academic year. (Photo: Don Lyman)

[KIDS TALKING; TEACHER CLAPS FOR ATTENTION]

LYMAN: I found myself among perhaps the only people with more questions than journalists: fifth graders.

SCHULER: You guys have so much curiosity about turtles! This is amazing, yes.

LYMAN: Chris Denaro’s students grilled Emilie Schuler, the Director of Programs and Operations at Grassroots Wildlife Conservation, about everything from how many turtles are left in the world, to potential hazards the littlest ones face.

KID: Do people step on those turtles?

SCHULER: They might. Yeah I’m sure and a small turtle like this, it probably could get crushed by a person stepping on it.

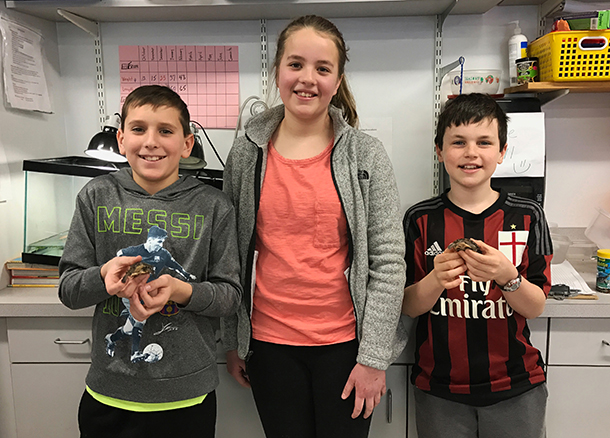

LYMAN: The kids were in the midst of a yearlong project to take care of two baby turtles, to give the hatchlings a head start in life, so they’d have a much better chance of surviving to adulthood and boosting the threatened species’ numbers when they’re released in the spring. One of those babies was from Turtle 2028, the mother we followed starting in July of 2016. By now the kids were pros at feeding the turtles, giving them fresh water and weighing them, but they still had lots to learn about some amazing things the hatchlings – which they’d named Tsunami and Squirtle -- could do.

SCHULER: Okay, so today we’re gonna be learning all about your turtles and some really cool superpowers that your turtles have. Some things that turtles can do that humans can’t do. Did you guys know that turtles have superpowers?

KIDS: No…. Yes…

LYMAN: During the harsh New England winters, those superpowers are essential for survival. Tsunami and Squirtle had it easy in their warm and artificially-sunny tank, but the kids who cared for them always had to bundle up during recess. We humans have to keep our bodies near a toasty 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. If a human’s body temperature drops below that by even a few degrees, we can quickly succumb to hypothermia. But Blanding’s turtles can chill to just above freezing.

SCHULER: Can a turtle’s body, Is it okay for a turtle for its body to be 33 degrees?

KIDS: Yeah… No…

SCHULER: Yeah! Right, that’s the really cool thing. It’s like kind of a superpower of turtles and of reptiles that they can have their body so, so, so cold. They can drop their body temperature like that and still be fine.

LYMAN: In order to still be okay with such a low body temperature, Blanding’s turtles have to slow down, waaaay down.

SCHULER: They’ve measured turtles that are this cold, and their heart was beating only one time every ten minutes.

KIDS: Whoa!!!!!

LYMAN: It sounds incredible, but that’s normal for turtles in winter, part of a nifty adaptation that allows them to slow their metabolism way down. And when that happens, they need a lot less oxygen. They still need some and can absorb small amounts through their skin. And they have another trick up their shell.

SCHULER: So turtles have the ability to hold their breath for a really, really, really long time.

LYMAN: Like – for months.

Ian, Sienna, and Owen with their class’s two Blanding’s turtle hatchlings. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

SCHULER: Scientists have even done studies where they’ve purposely, they’ve put turtles in water where they’ve bubbled out all the oxygen. Those turtles stayed under the water super-chilled for five months.

KIDS: What?!!? Oh my!

SCHULER: So those turtles were holding their breath for five months. Is that a cool superpower or what?!

KID: That’s cool.

LYMAN: But a metabolism that’s barely detectable is not so great for growing up big and strong.

SCHULER: So. Your Blanding’s turtle cousins that are outside, right – Tsunami has cousins that are not lucky enough to be in classrooms today are outside. Maybe, right, in the swamps of Great Meadows under the ice right now. And they are gonna be surviving over the winter. Pretty cool stuff that they can do that. But those cousins that are out in the winter right now, are they gonna be growing like Tsunami?

KIDS: No.

SCHULER: No. So even if they were the same age as Tsunami, come April or May, when it starts getting warmer and they come out, what’s the size difference gonna be between Tsunami and their cousins?

LYMAN: The answer: around 7 or 8 times the weight! That’s the main reason why the head start program is proving so valuable for boosting Blanding’s turtle population numbers. In just eight months, the kids make the baby turtles look like four-year olds, so they’re less attractive to predators like raccoons, herons, and bullfrogs, and much more likely to make it out in the wild.

[SOUND OF SCHOOL BUS PARKING]

DENARO: Hi, how are you? Nice to see you again.

LYMAN: A few months later, on a sunny June morning, it’s time for Tsunami and Squirtle to set off on their own.

[SOUNDS OF CLASS CHATTERING]

LYMAN: We meet up with the Carlisle School fifth graders at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge in Concord, Massachusetts, where Bryan Windmiller, the Executive Director of Grassroots Wildlife Conservation, is back in his waders with an assistant.

WINDMILLER: Good morning, guys.

STUDENTS: Good morning.

WINDMILLER: So, I’ve met you guy. I’m Bryan Windmiller. This is Benji Miranda, who works with me. We’ve got a beautiful morning to go check out the habitat where your turtles are going to be living.

[FOOTSTEPS ON PATH, RED-WINGED BLACKBIRD SONG]

LYMAN: The class starts down the tree-lined path that leads to the ponds at Great Meadows. It’s a pleasant spot. Beyond the trees cattails wave in a light breeze over the deep-blue ponds. Butterflies and red-winged blackbirds flit through the air, and occasionally you might see a Great Blue Heron take to the sky. Yet while it looks natural, it’s very much not.

WINDMILLER: All around here we have a real mix of plants & animals that are both from here, that started out here so they’re native. And there are also lots of species that got here only recently, because people, whether on purpose or not, have brought them. These beautiful smelling roses, right? I’m getting all the perfume from these guys. This is an Asian rose. It’s called Multiflora rose. So it’s only here because people brought it here. They thought it looked good, the blossoms smell really good, and now it’s all over the place.

LYMAN: Invasive species like purple loosestrife, Asian water chestnut, American lotus, and European carp have affected the makeup of flora and fauna here. And even the ponds themselves are not natural.

WINDMILLER: This whole place, as we walk along, you’ll see there are two big ponds that extend on either side. And this place is called Great Meadows, right? It’s not called Great Ponds. 80 years ago these were kind of scrubby meadows where people earlier in history from Concord used to graze their cows.

LYMAN: Then a man named Samuel Hoar, who owned 250 acres of the land known as “Great Meadows”, decided to build low earthen dams, or dikes, to hold water within the meadows, so that he could hunt the waterfowl that would be attracted to the ponds. But the change wrought by a private landowner who wanted to hunt ended up having a positive impact for some species.

WINDMILLER: We all know about all different ways in which people can affect the environment in ways that makes it harder for wild animals to live there. But in all kinds of ways, too, people can change the environment to help different kinds of wild animals. Whether it’s on purpose – Samuel wanted there to be more ducks so he could hunt them – but Samuel also made this better Blanding’s turtle habitat.

LYMAN: The turtles were here before the artificial ponds, and their population got a nice boost from the extra habitat. Then, as residential developments went up near Great Meadows in the latter half of the 20th century, and the turtles lost nesting habitat and fell victim to automobile traffic, their numbers dropped again. They’re now a threatened species in Massachusetts, so Grassroots Wildlife Conservation is working to get the adult population back to 200 from the 50 or so Blanding’s Turtles that live at Great Meadows now.

Students walk along the path dividing the man-made ponds at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge before releasing their turtles into the ponds. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

[FOOTSTEPS ON GRAVEL PATH]

LYMAN: On the straight-as-an-arrow dike that divides the two man-made ponds, the group stops a couple times to check turtle traps Bryan and Benji had set earlier that morning.

[SPLASHING SOUNDS]

MIRANDA: So these big ones are the ones we usually try and find the adult Blanding’s turtles in.

LYMAN: Neither trap has any Blanding’s turtles, but there are several pretty painted turtles.

WINDMILLER: Anybody wanna hold this guy? So if you hold this guy, just remember, right? He’s a wild turtle. So, if you put your finger right in front of his face, what might he do?

KIDS: Bite it.

WINDMILLER: Bite you on the finger. So don’t put any part of your anatomy right in front of his face.

LYMAN: Soon it’s time to head back down the path to the parking lot. There’s a big metal observation tower at one end, where birders and other nature enthusiasts can peer down across the ponds to spot the many wildlife species that call this place home. Bryan gathers the group at its base to record some final data points about Tsunami and Squirtle before they’re released, and to deepen the notches in their shells that will help identify them when they’re recaptured, perhaps years later.

WINDMILLER: All right, what have we got?

KID: Seventy-four…

WINDMILLER: Seventy-four point zero. Thank you Squirtle. Okay, so, who’s got the data sheet? Awesome. So he’s now, right, seven times heavier than he was when you got him, and when he hatched he would have probably been even a little less than that, right? So probably eight times heavier now. Which is a huge difference. And when they get to be fully adult, right? In their late teens or early twenties, they get to be…A big Blanding’s turtle around here will be around 1,800 grams. So you guys need to get back, and Tsunami and Squirtle need to get going. So, if you want to go up on the tower…And you can array yourselves, some of you on the top, some of you on the stairs.

[FOOTSTEPS ON TOWER STAIRS]

LYMAN: From the tower they watch as Bryan and Benji wade between cattails, to a nice shallow spot in the ponds.

KID 1: Nooooo they’re leaving! Guys, the turtles are leaving .

KID 2: They’re going away! .

KID 3: It’s their first time in the water other than their tank.

WINDMILLER: So, first we’ll let Squirtle go. Do you guys wanna say goodbye to Squirtle?

KIDS: Bye, Squirtle!

WINDMILLER: So now we’ll let Tsunami go. You guys can say goodbye to Tsunami.

KIDS: Bye Tsunami!

LYMAN: One kid, Owen, isn’t quite sure how to feel about saying goodbye.

OWEN: I liked watching them grow, ‘cause it made me -- It just made me happy to see them getting bigger and that they’d be released. I mean I’m happy that they can go, but I’m sad we can’t take care of them anymore because they’re so cute. So it’s like melancholy.

Bryan Windmiller and Benji Miranda wade between cattails at Great Meadows to release “Tsunami” and “Squirtle”. (Photo: Don Lyman)

LYMAN: What do you wish for the turtles?

OWEN: I want them to get really large and die naturally, not from a predator. Even though that is kind of naturally. But still.

LYMAN: Judging by the high survival rates of turtles that have gone through the head start program in years past, Owen may very well get his wish.

WINDMILLER: Actually, what’s really cool is we just found a turtle who is from 2028, who was released last year. The previous class found him right about here, walking across the path.

LYMAN: And a few days later, as night fell, exactly a year and one day after number 2028 laid the eggs that would include Tsunami, Bryan reported that she was just finishing up her nest in someone’s front yard, across the street from where she laid her eggs last year. The eggs looked normal. There were eight of them. And since Turtle 2028 had chosen a recently-delivered mulch pile for her nest, Bryan and his team gently moved them to a safer spot in the earth a few feet away. All summer long they’ll incubate in the warmth of the nest. And then, one day in autumn, these young Blanding’s turtles will poke through their shells, crawl up through the earth, and go to school.

For Living on Earth, I’m Don Lyman in Concord, Massachusetts.

Related links:

- Grassroots Wildlife Conservation’s Blanding’s Turtle Monitoring and Headstarting project

- More about the Blanding’s turtle from the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife

- Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, the new home of “Tsunami” and “Squirtle”

[MUSIC: Mandala Octet, “The Last Elephant, Pt. 2” on The Last Elephant, Accurate Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up...how cultural bias can create roadblocks for conservation. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Poncho Sanchez, “Willow Weep For Me” on Afro-Cuban Fantasy, written by Ann Ronnell/arr.Dan Weinstein, Concord Picante Records]

White Man’s Game

An elephant in Southern Africa. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. For thousands of years humans have been changing the environment, but the Industrial Revolution put change on steroids, with Europeans able to explore and exploit some of the remotest natural areas remaining. And no place was more intriguing than Africa.

Today there ware numerous efforts to halt the rapid loss of species and habitat, funded in part by the profits from modern business. But writer Stephanie Hanes says the promise of saving what’s left of nature can sometimes be imperiled by the narrow cultural lens employed by people from the developed part of the world. Her new book focuses on efforts to rebuild Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique, after it was denuded of its animals during a horrific regional conflict. It’s called “White Man’s Game: Saving Animals, Rebuilding Eden and Other Myths of Conservation in Africa,” and she joins me now.

Stephanie Hanes, welcome to Living on Earth.

HANES: Oh, thanks so much, Steve.

CURWOOD: What led you to write this book, "White Man's Game"?

HANES: I was working as a foreign correspondent in Southern Africa and I had just started to write about different environmental stories and different conservation stories, and when I first began doing that, I had gone in with a really simplistic idea of what the story lines were, that there's a good guy, that there's a bad guy, and that the people who are trying to save animals are on the side of the good, and then the bad people are trying to hurt them. And as I started reporting, I realized that it was much more complicated than this, much more interesting, much more political. And in a lot of ways, my book, "White Man's Game," stems from this. I wanted to go under the surface and try to understand why our conservation efforts weren't working the way that we wanted them to.

White Man's Game book cover. (Photo: Courtesy of Stephanie Hanes)

CURWOOD: In your book you talk about how Africa became so associated with the idea of adventure. You also say that often our stories of Africa and nature there are, well, they're really about us, especially, perhaps, in our efforts to provide aid. What brought you to this realization?

HANES: Well, there is a long history of western explorers and adventurers going into different parts of Africa and then bringing back these spectacular stories, and in a lot of ways we've never really gotten away from that narrative. And you see that today in the safari brochures that promise people, you know, the African experience of a lifetime, and here is your African adventure. And as I was reporting about both conservation issues and development aid, I saw these themes of adventure come up again and again and again. And they did seem to be a lot more about the travelers than the people or creatures that actually live there.

CURWOOD: You call your book "White Man's Game". To what extent do you think racism is a problem in these conservation efforts? I'm thinking of here in the United States, for example, that the National Parks system was whites-only at the very beginning. How much do you think the difficulties in conservation effects there are due to the racial divide?

HANES: There's a nasty history of national park creation in southern Africa. Those parks were primarily designed for colonial white people and often involved removing black Africans who lived in them to other places. So, what's seen as a conservation triumph in a lot of these places began with personal tragedies for the people who live there. I wouldn't want to accuse people who are going in now with conservation goals of racism. I don't think that it’s as simplistic as that, but I do think that these racial tensions and these cultural tensions are clearly there.

Elephants in Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique. (Photo: F Mira, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

Somehow, our pattern, when we've gone into developing parts of the world, which also happen to be those parts of the world we often find our ecological hotspots in, we don't see the complexity there. We come in with an idea of what is good and what is effective and what we think should happen and often these thoughts are really well-meaning. But we don't realize that we're not going onto this blank slate, we're not going onto a place that just needs help. If only we could come and add our expertise. We're going into incredibly complex and very different places.

CURWOOD: What you're saying, essentially, is that there’s a problem -- you call it the white man's game -- some would have called it in the past perhaps the so-called “white man's burden”?

HANES: It's a colonial term for the idea that it was the responsibility of the civilized North to come and help the South, go and help Africa, and it was the white man's burden to uplift the rest of the world. There's also a great Kipling poem that takes a harsh look at that. And that's actually where I came up with the name of the book, and “game” being game parks or game animals as well as the other indication.

CURWOOD: So, Mozambique, of course, has a difficult and complex history, and at the end of the day much of the sort of charismatic megafauna that we know from Southern Africa -- the elephants, the lions and leopards and all that -- were gone. They were dead in much of the country. And you write about Gorongosa, where philanthropist, conservationist, entrepreneur, Greg Carr went to this particularly beautiful place to try to remake what had been a national park. Why did you pick Gorongosa as your case study for looking at what you call sometimes “myths of conservation” in Africa?

Gorongosa Park at sunset. (Photo: F Mira, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

HANES: I first ended up at Gorongosa because I was reporting a series with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting about the intersections between environmental degradation and conflict zones. And in the course of reporting that series, I spoke to a source who said, "Well, if you're looking for a good news story, maybe check out the Gorongosa National Park in central Mozambique." And I thought, “Great, this is the one good-news piece that I can have in this series, and it will be an easy story to do.” And I went there, and in a way it was a really easy narrative, at first. It was a place that had been destroyed that was coming back, that was going to be beautiful again.

But there was also something more. And the longer I stayed there, and the longer I reported, the more I saw that there were all these complexities going on underneath the surface, and that narrative that was so easy wasn't the narrative to the people who live there, to at least some of the people who live there.

CURWOOD: You talk about the tension between the people who live near the park and the park itself. In fact, you open your book with a scene of a person who had worked putting up a fence to keep in some transferred animals after he was let go from that job coming back and killing some of those animals to make money.

HANES: The person that I write about in the book got a temporary position at the park to help build a sanctuary fence for new animals that the park was bringing in from other countries. He did end up going back and killing some of those animals and was eventually arrested for snaring still other animals in the park. He was a poacher, and he said that unapologetically. There wasn't the same morality attached to it. He was poaching because he needed to feed his family and make a couple of extra dollars so he could buy schools supplies for his little kids. The reaction was then to bring him and put him in forced work duty for a number of months to have him pay off the fines for his poaching.

The “Serra de Gorongosa” mountain complex, close to Gorongosa National Park. (Photo: Ton Rulkens, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

And so, what started as this effort to give people jobs in the park and to build goodwill and to convince them that this national park was really important for them, to be some place that should be protected, turned for this family and this person into yet another instance of outsiders coming in and hurting them.

CURWOOD: In your book, you talk about how well-meaning Westerners often seem to end up lecturing the indigenous people about their own environments. In particular, E.O. Wilson -- very smart biologist, developed the biophilia hypothesis -- goes to organize a bio blitz there. I get the impression you think that Wilson's efforts there were rather condescending. I mean, how do you achieve a balance between respecting local expertise and achieving conservation goals?

HANES: I'm not sure if I would say that E.O. Wilson's actions there were inherently condescending. I think that there is a problem with people who don't have any familiarity with a particular place going in and declaring themselves to be the experts there. There is, they certainly hold an expertise, and I'm not trying at all in the book to negate that. I think that Wilson's work is incredible.

There are a number of instances where Western conservationists have gone to places and have said that people living there should change their behavior in this way or that way. A lot of times local villagers are presented as uneducated or that they are primitive. They might not have the same scientific background or education, but there's an awful lot of knowledge there, and I think that that gets lost a lot when people come into a place unaware.

An African rondavel-style building in Gorongosa National Park. (Photo: F Mira, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: One of the big premises of the whole Gorongosa effort is that tourists will be invited. How welcome, in fact, are tourists to this place by the people who have lived there literally for thousands of years?

HANES: Well, there are two answers here. The first one is that there are not many tourists in Gorongosa right now. That was the original goal. That goal has shifted, and that’s something that is another issue with conservation programs that I saw when I was reporting there, is conservation programs merge increasingly into development aid programs. But going back to tourism, that's a big question throughout southern Africa. Who are these parks geared toward? Originally, this project started with the idea that there would be a huge number of foreign and Mozambican tourists coming, making the parks sustainable with the tourism fees, and that hasn't happened at all.

CURWOOD: Gorongosa Park, which Greg Carr was working mightily to repopulate with animals and conserve, the national government awarded – if I could say that word -- Mount Gorongosa, a very ecological place. At the end of the day, it led to people at the park pushing to resettle the people who were already there. Tell me that story and the impact of those efforts.

HANES: When Greg Carr and his scientists arrived, they started worrying that deforestation on that mountain was ruining the ecosystem, and fairly soon would destroy the entire ecology of the park if it wasn't stopped. So, the park began lobbying the central government, which happens to be an opposition government, from money of the people within that particular area. So, they are on different political sides. The park started lobbying the central government to put the mountain within the park's borders. Eventually, they did this.

Gorongosa National Park Patron, Leader & Philanthropist Greg Carr. (Photo: USAID Mozambique, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

When I was there, many of the people who lived on the mountain told me that they were incredibly upset about this. For them, this mountain was an incredibly important spiritual place. It had also, for a long time, been the epicenter of resistance there. People didn't want the park to own it. They told me they were worried about this outsider coming and stealing their mountain. Greg said he didn't want to force people to resettle. He expected people would move down on their own. Some people on his staff said they did want to force people to resettle.

What happened is that a few, a little bit after the park got control of the mountain, violence broke out there again in a resurgence of civil war tensions which had been quiet for quite a while. And a lot of the people had to flee the mountain on their own. And a lot of people came down because they wanted to be away from the fighting.

P

CURWOOD: In your book, Stephanie, you talk about the traditional culture there and the role of spirits. For example, you point out that when Greg Carr came up Mount Gorongosa, he showed up in a red helicopter, which was a red flag, culturally. That helicopter represented a “gamba”, the spirit of a soldier who been killed far away from home and was really pretty upset, and would mean that more trouble was coming. In reality, conflict returned to the area. So, in other words, folks who looked to the spirit to tell history said, we'll have conflict, and sure enough conflict came. And those weren't the people who pushed the conflict, by the way. They just said the conditions of conflict had now been set.

Gorongosa Park entrance sign. (Photo: F Mira, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

How did that make you feel when you understood that, and to what extent do conservationists need to pay attention to this question of traditional culture and the spirits?

HANES: I think that conservationists need to pay a lot of attention to the cultures of areas in which they would like to work. What I was surprised by and stunned by, in a way, was how accurately the people who lived there had predicted what would happen. You can't debate with the fact that there were these instances that happened, that people who live there said were part of this pattern of spiritual displeasure which would lead to violence, and indeed it led to violence. So, you know, in terms of how I felt, it was just another example and another piece of proof for me that stories are so very powerful, and that to ignore them or to belittle others as not being logical or scientifically-factual or truth in the conservation, Western, scientific, progressive sense of it doesn't mean that they're any less true. And those conflicts do create real violence, those conflicts of stories.

Renha Kueri (right) with her family. They live on Mount Gorongosa in Mozambique. (Photo: Ton Rulkens, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Is this a natural history book or a philosophy book?

HANES: I think that this book holds incredibly important truths for the way that we are in the world right now. In a lot of ways, I saw Greg Carr as a metaphor for America and our country, and the way that we go about the world. We're connecting with each other more in some ways, and we're communicating and understanding each other less. So, in a way it is a philosophy book in the sense that it is looking at a really big question of, how do we get past these divides that are tearing up everything from our country to our world. So, I would say both. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: Before your book was even published, you faced a lot of criticism about it, so much so that you essentially dedicated a chapter to the criticism of the very end of your book. How do you think people are going to respond now, that your book is actually out?

HANES: I don't know. I'm glad that it will give people the chance to read it. Now, I wasn't surprised that there were some people who were upset by the book. People are working on what they believe is good. It's not easy to be criticized. I was surprised that people who are scientists and who work in fact-based missions had such a virulent reaction before they had never read a word. That seemed like a problem to me.

CURWOOD: Your overarching point in this book seems to be that stories often become romanticized and through that perspective become, well, rather limited. Gorongosa Park, although not a bad thing, comes with consequences, it seems that you're telling us. Why do you think this is important for readers to understand?

.jpg)

Author Stephanie Hanes (Photo: Tim Young)

HANES: If readers don't understand the complexity of stories, if we don't really understand and believe that there are other conflicting stories, then we will continue to go about trying to act out these narratives that we have and continue to not do very well. In conservation, we have incredible biodiversity loss in this world. We have incredible conservation problems, and I think it makes sense to stand back and say, “OK, maybe we're not doing something right here.”

CURWOOD: Stephanie Hanes' new book is called "White Man's Game: Saving Animals, Rebuilding Eden and Other Myths of Conservation in Africa". Thanks for taking time with us today, Stephanie.

HANES: Thanks so much, Steve. It was fun.

Related links:

- “White Man’s Game: Saving Animals, Rebuilding Eden, and Other Myths of Conservation in Africa”

- More about Stephanie Hanes

- PBS.org: “About Gorongosa National Park”

- Listen to a recent LOE interview with E.O. Wilson

[MUSIC: Empire Brass, “Pour invoquer Pan” on Music of France & Spain, composed by Claude Debussy, Telarc]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth – Native American activists couldn’t stop the Dakota Access pipeline, but they won’t give up.

GOLDTOOTH: It’s not just one pipeline we're fighting against. It's not just Standing Rock. It's this global effort to keep fossil fuels in the ground and build really good solutions.

CURWOOD: But oil and gas producers say pipelines give energy security and create jobs. That’s next time, on Living on Earth.

[SOUNDS OF A SOUTHERN AFRICAN FOREST; BABOONS CALL IN DISTANCE]

CURWOOD: We take you now to a 300-foot-high cliff deep in a forest in Zimbabwe, not too far across the border from Mozambique.

[FOREST SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: It’s dawn, and baboons are joined by many different birds, amphibians, and insects to create this wilderness opera.

[BABOONS CALL IN DISTANCE]

CURWOOD: Bernie Krause made this recording for his Wild Sanctuary Series. He called it “African Safari Zimbabwe.”

[SOUNDS OF SOUTHERN AFRICAN FOREST]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Matt Hoisch, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Olivia Reardon, Rebecca Redelmeier, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Jake Rego engineered our show, with help from Zack Ronald. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth