Dangerous Drifting Particles

Air Date: Week of August 11, 2017

_8633.jpg)

New research into long-range transportation of PAHs explains the levels of these pollutants recorded in remote places such as the mountains of Glacier National Park. (Photo: Tobias Klenze, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are toxic air pollutants produced by combustion linked to lung cancer and other serious health problems. They’re mostly seen as a local bad air issue, but recent findings suggest that these tiny particles travel long distances and significantly increase overall health risks. Research co-author and Oregon State Chemistry Professor Staci Simonich, explains her findings to host Steve Curwood.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons sound like some exotic fragrance, but they’re actually toxic air pollutants produced by fuel combustion that have been linked to lung cancer and other serious health problems. Currently, these compounds are treated as a local issue in places with smog and bad air quality, but recent findings suggest that these pollutants may actually travel long distances and affect people across the globe. And according to a recently published paper, this significantly increases the overall health risk associated with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, PAH for short.

Staci Simonich is a Professor of Chemistry at Oregon State University and co-author of this research, and she joins us now to discuss these findings. Welcome to Living on Earth.

SIMONICH: Thank you. I'm happy to be here.

CURWOOD: Now, you've done a great deal of research on these polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Please describe to our listeners what these compounds are and what we know about them.

SIMONICH: Well, they've really been around since we had combustion. So, whenever there's been fire we've created these PAHs, and so we're still learning about these compounds. We're still learning about how they move in the environment and what their effects on people and the environment are.

CURWOOD: Now, you recently published in the proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences how these compounds move, and how people are exposed to them in rather surprising ways, I think. So, please describe this research and what you did find.

SIMONICH: Well, my own group here at Oregon State University, we've been studying air pollution and PAHs and how they move from source regions including Asia and China, how people are exposed there, and we've been studying how they transport across the Pacific Ocean to the US west coast. So, for about 16 years we've been studying this transport, how much in the US is coming from other countries, how much is from our own sources, and part of the discrepancy in this was that the measurements we were making at high elevation, remote areas were higher than the models predicted. And so this piece of work really puts together experiments in the laboratory, modeling, and field measurements to come up with a new explanation for why these PAH concentrations are higher.

Pollution from coal and other fuel combustion not only exposes people to PAHs locally, but can transport them thousands of miles to other countries (Photo: Fredrik Rubensson, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, what did you suspect as the reason that these chemicals were being found in places that really didn't seem like that was a place you would find them?

SIMONICH: Well, there was some unexplained reason in terms of the modeling side, and what we found with our researchers at Pacific Northwest National Lab is that on particles, these PAHs are actually shielded or protected from reactions in the atmosphere. And so we're talking about particles that are on the size less of than one micrometer in diameter, so about five or six of these particles fitting across the width of a human hair. Because they're such fine particles, they don't settle out near source regions, so near, let's say, major urban areas, they get pulled into the atmosphere and can undergo transport in high elevation winds where they're intercepted, and they ultimately come out of the atmosphere due to rain and snow.

CURWOOD: Part of your paper discusses what you call a ‘shielding’ effect. What do you mean by that?

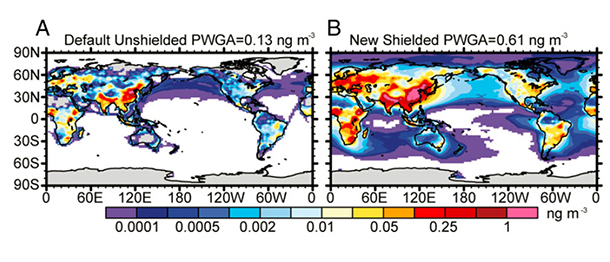

Figure from Shrivastava et al.’s 2016 paper in PNAS showing how inclusion of long-range transport into PAH models dramatically increases predicted concentrations worldwide (Photo: Shrivastava, Manish, et al. "Global long-range transport and lung cancer risk from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons shielded by coatings of organic aerosol." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114.6 (2017): 1246-1251.)

SIMONICH: So, we mean that, after a PAH is emitted on a particle from the tailpipe, that it can immediately be surrounded by atmospheric reactions that create a layer over these PAHs and protect them from reaction with oxidants in the atmosphere. So, the end result is, they travel long distances and don't degrade in the atmosphere.

CURWOOD: Where was the most surprising place that you found these cancer-causing chemicals when you did this research?

SIMONICH: So, we find them in any place we look, so, of course, whether it's a major urban area or on islands and also mountaintops at 2,700 meters. Actually some of the places that surprised me the most and over the years, we found them in Glacier National Park at relatively high concentrations, and we were able to link them to an aluminum smelter outside of the park.

CURWOOD: So, how are people exposed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons that have been transported a long distance?

SIMONICH: In daily life, the main sources are diet and smoking and indoor air exposure, but through the long-range transport it's just part of our outdoor air, and outdoor air becomes indoor air.

CURWOOD: So, we know that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are considered carcinogenic. I know there's a lot of focus on lung cancer, but what other cancers might they be connected with?

Open cooking fires, such as this one in Nanyuki, Kenya, have been a source of human exposure to PAHs for thousands of years. (Photo: Alexander Metzger)

SIMONICH: You're right. This study focused on lung cancer, and that's because we have most of the data available around lung cancer and atmospheric particulate matter, but we're finding that PAHs have other effects on humans and other organisms, can include cardiovascular effects, and even developmental effects when a fetus is developing.

CURWOOD: So, there's a chart that comes with your study that shows that the level of risk is elevated on both coasts of the US and much of sub-Saharan Africa. Why do you think that might be?

SIMONICH: Well, let's take the US as an example. Now we've understood that the concentrations are actually higher on the US west coast than we had previously modeled. So that's coming from emissions in Asia, primarily China, that are transported long distances, and on the east coast of the US we have our own sources of PAHs, and our modeling now suggests that those emissions within the US are transporting to the next state and other states downwind with the winds blowing primarily from west to east.

CURWOOD: Now, there's some articles about your research that have mentioned that new models which consider this long-range transportation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons have predicted a four times greater cancer risk than previously. In fact, the risks now exceed World Health Organization standards. What implications does this have on how these emissions should be regulated in the future, do you think?

SIMONICH: Well, I think we have to remember that the major areas of risk are major megacities in parts of China and parts of India where the air quality now is certainly among the poorest in the world. But I always like to say, “What goes around comes around,” so it drives home that idea that we're a connected atmosphere, right? And that what happens in one part of the world impacts other parts of the world. So we're all united in one atmosphere.

CURWOOD: So, tell me, what are some of the ways that exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons might be reduced, considering these new findings?

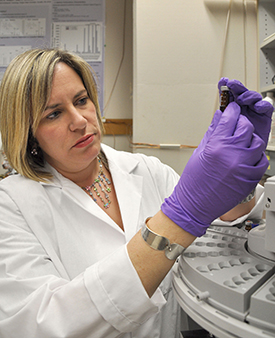

Staci Simonich examines an air pollution sample in her lab at Oregon State University. (Photo: Tiffany Woods / Oregon State University, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

SIMONICH: Well, I think you in our own personal daily lives, not smoking is a big one. Thinking about our diet, and personally I love barbecue and I love grilling, so I do it in moderation, and I eat it with a balanced diet. It's not something I've given up.

So, we can think about our own personal exposures, but then on a national and international scale we can think about technologies that help reduce emission of PAHs from coal combustion, from biomass combustion. So, in China the main sources of PAHS to the atmosphere are coal combustion and biomass combustion followed, third, by automobiles. So, it's really controlling those sources of particulate matter that have PAHs on them that can play a large role in reducing global atmospheric concentrations of PAHs.

CURWOOD: Staci Simonich is a Professor in the Department of Chemistry at Oregon State University. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

SIMONICH: Thank you.

Links

The full research article from Manish Shrivastava and Staci Simonich’s research team

Oregon State University press release on long-distance transport of PAHs

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory press release on long-distance transport of PAHs

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth