August 11, 2017

Air Date: August 11, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Dangerous Drifting Particles

View the page for this story

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are toxic air pollutants produced by combustion linked to lung cancer and other serious health problems. They’re mostly seen as a local bad air issue, but recent findings suggest that these tiny particles travel long distances and significantly increase overall health risks. Research co-author and Oregon State Chemistry Professor Staci Simonich, explains her findings to host Steve Curwood. (07:35)

Bad Air As Stock Market Bear

View the page for this story

High levels of fine particulate air pollution can lower the stock market, a team at Columbia University has found. Team leader Matthew Niedell, an associate professor at Columbia University, discusses the findings with Host Steve Curwood. (07:30)

War Veterans Farm For Health

/ Sean PowersView the page for this story

Veterans must often wait months for health appointments at V-A facilities. So a combat vet in Georgia founded a farm designed to immerse returning soldiers in the restorative rigors of working the land, a special boost for those suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Reporter Sean Powers has the story. (06:20)

From Orange To Green

View the page for this story

Former prison inmates are planting trees in Baltimore, helping to rejuvenate some of the city’s tough poor and crime-ridden neighborhoods. Alex Smith, head of field operations for the Baltimore Tree Trust spent 15 years in prison. He tells host Steve Curwood how planting urban trees is turning lives around and remaking the city. (11:05)

Finding New Tyrannosaurs

View the page for this story

Sixty-five million years ago, T. Rex was the biggest carnivore on Earth, and to this day it looms large in our imaginations. But science now knows this iconic tyrant lizard was but one of more than two dozen species of tyrannosaur, a diverse family that lasted 100 million years and came in many shapes and sizes. David Hone, author of The Tyrannosaur Chronicles, tells host Steve Curwood what we know about these extraordinary creatures. (14:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Staci Simonich, Matthew Niedell, Alex Smith, and David Hone

REPORTERS: Sean Powers

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood.

Dirty air hangs around factories and manufacturing plants, but some kinds of air pollutants can travel across continents and around the world.

SIMONICH: The major areas of risk are major megacities in parts of China and parts of India, where the air quality now is, you know, certainly among the poorest in the world, but I always like to say, “What goes around comes around,” so it drives home that idea that we're a connected atmosphere, right? And that what happens in one part of the world impacts other parts of the world.

CURWOOD: Also, calling in farm animals to help war veterans deal with post-traumatic stress disorder.

JACKSON: Animals don’t care about your bad day. They’re going to come up, and they’re like, “I want you to pet me.” You’re like, “Ok, but I’m feeling really mad right now, but I’m petting you.” And, man, they don’t know the amazing stuff they’re doing for our vets who come through.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Dangerous Drifting Particles

_8633.jpg)

New research into long-range transportation of PAHs explains the levels of these pollutants recorded in remote places such as the mountains of Glacier National Park. (Photo: Tobias Klenze, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons sound like some exotic fragrance, but they’re actually toxic air pollutants produced by fuel combustion that have been linked to lung cancer and other serious health problems. Currently, these compounds are treated as a local issue in places with smog and bad air quality, but recent findings suggest that these pollutants may actually travel long distances and affect people across the globe. And according to a recently published paper, this significantly increases the overall health risk associated with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, PAH for short.

Staci Simonich is a Professor of Chemistry at Oregon State University and co-author of this research, and she joins us now to discuss these findings. Welcome to Living on Earth.

SIMONICH: Thank you. I'm happy to be here.

CURWOOD: Now, you've done a great deal of research on these polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Please describe to our listeners what these compounds are and what we know about them.

SIMONICH: Well, they've really been around since we had combustion. So, whenever there's been fire we've created these PAHs, and so we're still learning about these compounds. We're still learning about how they move in the environment and what their effects on people and the environment are.

CURWOOD: Now, you recently published in the proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences how these compounds move, and how people are exposed to them in rather surprising ways, I think. So, please describe this research and what you did find.

SIMONICH: Well, my own group here at Oregon State University, we've been studying air pollution and PAHs and how they move from source regions including Asia and China, how people are exposed there, and we've been studying how they transport across the Pacific Ocean to the US west coast. So, for about 16 years we've been studying this transport, how much in the US is coming from other countries, how much is from our own sources, and part of the discrepancy in this was that the measurements we were making at high elevation, remote areas were higher than the models predicted. And so this piece of work really puts together experiments in the laboratory, modeling, and field measurements to come up with a new explanation for why these PAH concentrations are higher.

Pollution from coal and other fuel combustion not only exposes people to PAHs locally, but can transport them thousands of miles to other countries (Photo: Fredrik Rubensson, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, what did you suspect as the reason that these chemicals were being found in places that really didn't seem like that was a place you would find them?

SIMONICH: Well, there was some unexplained reason in terms of the modeling side, and what we found with our researchers at Pacific Northwest National Lab is that on particles, these PAHs are actually shielded or protected from reactions in the atmosphere. And so we're talking about particles that are on the size less of than one micrometer in diameter, so about five or six of these particles fitting across the width of a human hair. Because they're such fine particles, they don't settle out near source regions, so near, let's say, major urban areas, they get pulled into the atmosphere and can undergo transport in high elevation winds where they're intercepted, and they ultimately come out of the atmosphere due to rain and snow.

CURWOOD: Part of your paper discusses what you call a ‘shielding’ effect. What do you mean by that?

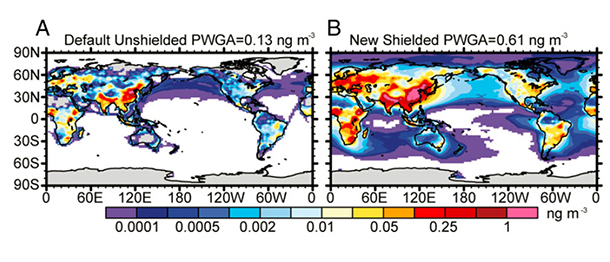

Figure from Shrivastava et al.’s 2016 paper in PNAS showing how inclusion of long-range transport into PAH models dramatically increases predicted concentrations worldwide (Photo: Shrivastava, Manish, et al. "Global long-range transport and lung cancer risk from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons shielded by coatings of organic aerosol." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114.6 (2017): 1246-1251.)

SIMONICH: So, we mean that, after a PAH is emitted on a particle from the tailpipe, that it can immediately be surrounded by atmospheric reactions that create a layer over these PAHs and protect them from reaction with oxidants in the atmosphere. So, the end result is, they travel long distances and don't degrade in the atmosphere.

CURWOOD: Where was the most surprising place that you found these cancer-causing chemicals when you did this research?

SIMONICH: So, we find them in any place we look, so, of course, whether it's a major urban area or on islands and also mountaintops at 2,700 meters. Actually some of the places that surprised me the most and over the years, we found them in Glacier National Park at relatively high concentrations, and we were able to link them to an aluminum smelter outside of the park.

CURWOOD: So, how are people exposed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons that have been transported a long distance?

SIMONICH: In daily life, the main sources are diet and smoking and indoor air exposure, but through the long-range transport it's just part of our outdoor air, and outdoor air becomes indoor air.

CURWOOD: So, we know that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are considered carcinogenic. I know there's a lot of focus on lung cancer, but what other cancers might they be connected with?

Open cooking fires, such as this one in Nanyuki, Kenya, have been a source of human exposure to PAHs for thousands of years. (Photo: Alexander Metzger)

SIMONICH: You're right. This study focused on lung cancer, and that's because we have most of the data available around lung cancer and atmospheric particulate matter, but we're finding that PAHs have other effects on humans and other organisms, can include cardiovascular effects, and even developmental effects when a fetus is developing.

CURWOOD: So, there's a chart that comes with your study that shows that the level of risk is elevated on both coasts of the US and much of sub-Saharan Africa. Why do you think that might be?

SIMONICH: Well, let's take the US as an example. Now we've understood that the concentrations are actually higher on the US west coast than we had previously modeled. So that's coming from emissions in Asia, primarily China, that are transported long distances, and on the east coast of the US we have our own sources of PAHs, and our modeling now suggests that those emissions within the US are transporting to the next state and other states downwind with the winds blowing primarily from west to east.

CURWOOD: Now, there's some articles about your research that have mentioned that new models which consider this long-range transportation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons have predicted a four times greater cancer risk than previously. In fact, the risks now exceed World Health Organization standards. What implications does this have on how these emissions should be regulated in the future, do you think?

SIMONICH: Well, I think we have to remember that the major areas of risk are major megacities in parts of China and parts of India where the air quality now is certainly among the poorest in the world. But I always like to say, “What goes around comes around,” so it drives home that idea that we're a connected atmosphere, right? And that what happens in one part of the world impacts other parts of the world. So we're all united in one atmosphere.

CURWOOD: So, tell me, what are some of the ways that exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons might be reduced, considering these new findings?

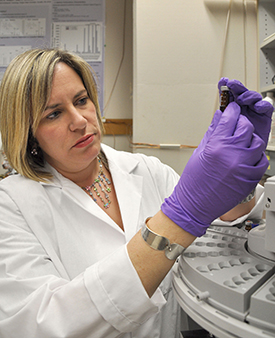

Staci Simonich examines an air pollution sample in her lab at Oregon State University. (Photo: Tiffany Woods / Oregon State University, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

SIMONICH: Well, I think you in our own personal daily lives, not smoking is a big one. Thinking about our diet, and personally I love barbecue and I love grilling, so I do it in moderation, and I eat it with a balanced diet. It's not something I've given up.

So, we can think about our own personal exposures, but then on a national and international scale we can think about technologies that help reduce emission of PAHs from coal combustion, from biomass combustion. So, in China the main sources of PAHS to the atmosphere are coal combustion and biomass combustion followed, third, by automobiles. So, it's really controlling those sources of particulate matter that have PAHs on them that can play a large role in reducing global atmospheric concentrations of PAHs.

CURWOOD: Staci Simonich is a Professor in the Department of Chemistry at Oregon State University. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

SIMONICH: Thank you.

Related links:

- The full research article from Manish Shrivastava and Staci Simonich’s research team

- Oregon State University press release on long-distance transport of PAHs

- Pacific Northwest National Laboratory press release on long-distance transport of PAHs

Bad Air As Stock Market Bear

The trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange, the site of Prof. Niedell and colleagues’ recent research on the impacts of particulate matter. (Photo: Ryan Lawler, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

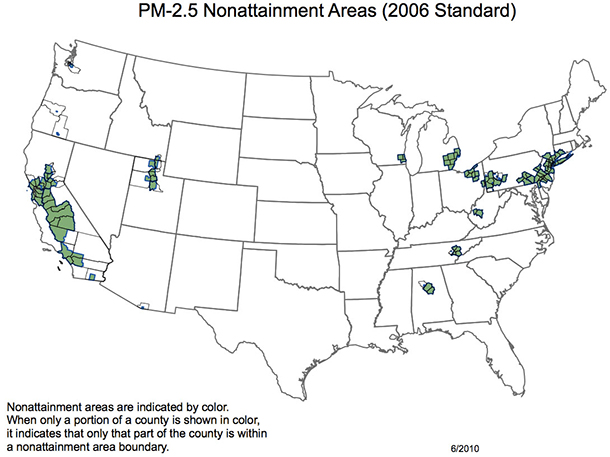

CURWOOD: People close to the stock market like numbers, and there is a new one that might catch their attention, two-point-5. That’s the size in microns of the tiny particles of air pollution that researchers at Columbia University say seems to change investor behavior, at least in New York City. When two-point-5 particulate matter pollution goes up, the market goes down by small but measurable amounts, says Professor Matthew Niedell. Here’s what his team was looking at and how levels of PM 2.5 pollution in Manhattan air could move the stock market.

NIEDELL: In this research what we were doing is building a lot of previous research that has been finding various effects of air pollution on the well-being of humans beyond just health. So, in this study what we wanted to do was look at its impacts on investors at the New York Stock Exchange and the relationship between fine particular matter and returns on the S&P 500.

The New York City skyline with haze of air pollution. (Photo: Nicolas Halftermeyer, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: When we talk about these particulates, what exactly we talking about?

NIEDELL: So, fine particulate matter are very small particulates less than 2.5 microns, something that you can't see with the human eye. They come from natural sources such as forest fires and volcanoes, but a lot of what we see in cities comes from combustion of fossil fuels. Given how small they are they're able to penetrate deep within our body, they pass through our lung barrier and into our blood where they can have effects that way. Because they're so small, that also makes them penetrate from outdoors to indoors.

CURWOOD: And I understand that you looked at the time of day that people are exposed to this?

NIEDELL: Right, so what we did was we had an air pollution monitor that was very close to the Exchange. Through that monitor, we had hourly measures of air pollution, and we were able to look at the particular hours at which air pollution was reaching a certain level and look at the returns on the S&P 500 on that day.

CURWOOD: And what did you find?

NIEDELL: First of all, we found when the entire day had a higher level of particulate matter we saw the S&P 500 dropped. But in particular we found that particulate matter levels, when they were higher in the morning and throughout the early afternoon, had the biggest impact on the S&P 500.

CURWOOD: So, what surprised you the most about these results?

NIEDELL: Well, what surprised us the most was the fact that we found any relationship at all. We had a small, little inkling that there might be a relationship between these two, but we were going a bit on a whim. There's a story for why there could be a relationship, but it wasn't the strongest story in the world, and we were surprised to find as robust of an effect as we found.

What's interesting about this is that in New York City the air quality is actually surprisingly good. So, if we're doing a study in Beijing or we're doing something in London, where air quality is generally worse, we might see much bigger changes.

CURWOOD: What was the story that suggested that maybe there might be something to be found here?

NIEDELL: So, the main story that we had in mind was that air pollution would be related to the mood and cognitive performance of traders. There's evidence that suggests, when people's mood drops, or their cognition underperforms that they tend to become more risk averse in the decisions that they make. They go away from stocks and shift toward bonds. Bonds are kind of safer bets, and stocks are riskier bets. So, if people are going away from stocks and going to bonds, we would see the price of the S&P 500 drop. It's not something that we've definitively proved in the study. What we do is, we look at something called the volatility index, which a lot of people use as a measure of trader fear, and what we find is that on days with higher fine particulates, we also see a decrease in that index which is used to indicate that there's an increase in trader fear, and we think that's suggestive of risk aversion being what's driving the results.

Fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) presents a significant health threat in some major cities in the United States, including New York City. (Photo: Environmental Protection Agency, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: How big a deal is this, when you say that a lot of PM 2.5, those fine particulates in the air, would depress the return on the S&P 500, and at the New York Stock Exchange? Just how much of a depression there?

NIEDELL: The effect isn't very big. A very large change in particulate matter is only leading to a pretty moderate to small size effect on returns. What we think is important about it is two things. So, the first is that there's a strong held belief that stock markets work efficiently, something called the efficient market hypothesis, that the price of a stock solely reflects the expected future profitability of a firm, but our research shows, which other research has shown before, is that there's more to it than just that. There's a role for moods and emotions and things like that in affecting a stock price.

The other thing that we think is interesting from a policy perspective is pollution is affecting the performance of workers in a sort of high skilled occupation in a very knowledge-based setting, and we think that has important implications for the effects on the economy in a broader level.

CURWOOD: Interesting. Now, as my friend Dave Brancaccio is fond of saying, let's do the numbers. How big is this effect on a really big day?

NIEDEL: On a really big day, if particulate matter goes from the bottom 25th percentile, or the best quartile, to the worst quartile, to 75th percentile, we would see that returns would decrease by two basis points, which is a .02 percent decrease, so it's not the most enormous effect, but we do see them. They are statistically significant effects, and they are somewhere in magnitude to the effects from other things that have been shown to affect returns.

CURWOOD: And when you say “basis points,” folks might think of that as simply two cents on a dollar. People make a lot of money on Wall Street squeezing, you know, a 10th of a penny out of transactions consistently.

NIEDEL: They do. They do. And it's interesting because we actually had that same idea to say, hey, can we use this as a way to make money off of this? If we know something about air pollution that the traders don't know.

Contrast between a rainy day and a smoggy day in Beijing, where Prof. Niedell suggests the effects of particulate matter on trading behavior may be more extreme. (Photo: Bobak Ha’Eri, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: How much, over time, do you think a savvy trader who knows of the effects of fine particulate pollution on the minds of traders there at Wall Street...How much money do you think could be made by somebody who is willing to short the market on those days?

NIEDEL: So, at this point it would hard for people to make money off of it. The way we see people make money in the stock market is if they have some information that other people don't have. So if you knew something about what air quality was going to be an area, and you knew that it would affect stock prices, then that might be an opportunity for somebody to make money off of it. But in this case, now that this research is out in the public, everybody has access to this information. So, it's not clear that somebody would have an advantage in using this information.

Matthew Niedell, Associate Professor in the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University. (Photo: courtesy of Matthew Niedell and Columbia University)

CURWOOD: Now, you study public health and the economics of it. If fine particulates are having this kind of impact on the minds of folks who are trading stocks, how might this be affecting the rest of our economy when we have this kind of pollution?

NIEDEL: Well, that's what we thought was the particularly interesting aspect of this study. It could possibly be affecting everybody. There's been previous work looking at particulate matter and its effect on workers in sort of manual, more physical labor settings, and this is showing that this work doesn't just apply to people that are in that sector, but it applies to a much broader sector, so these effects could be affecting everyone, even the two of us on a day like today depending on what pollution levels are like.

CURWOOD: Matthew Niedell is Associate Professor of Health Policy Management at Columbia. Thank you so much for taking time with us today.

NIEDELL: All right. Thanks a lot for having me.

Related links:

- Journal article: “The Effect of Air Pollution on Investor Behavior: Evidence from the S&P 500”

- Journal article: “Particulate Pollution and the Productivity of Pear Packers”

- The Washington Post: “New research shows air pollution might make you bad at your job”

- Harvard Business Review: “Air Pollution Is Making Office Workers Less Productive”

- Listen to our previous story: “Better Office Air Makes For Better Thinking”

MUSIC: Khaled, “Melha” on Kenza, arr. Steve Hillage, ARK 21 Records]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, greening the mean streets of Baltimore with some of the folks that used to make them mean. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth – stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: New Black Eagle Jazz Band, “Come Sunday,” on Higher Ground, CD Baby]

War Veterans Farm For Health

Veterans care for livestock and grow fresh produce at Comfort Farms in Milledgeville, Georgia. (Photo: Comfort Farms)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The U-S Department of Veterans' Affairs has been making efforts to ensure that veterans don’t have to wait too long for mental and physical health appointments at the V-A, after wait times spiked to over 30 days during 2016. But those long wait times sparked an imaginative and novel push in Georgia to improve care for vets by helping them connect with their roots… down on the farm.

Reporter Sean Powers of Georgia Public Broadcasting has the story.

[SOUNDS OF OUTDOORS, GOATS]

POWERS: On a 25-acre farm in rural Milledgeville, in Baldwin County, Jon Jackson looks through a gate separating him from his goats.

JACKSON: Animals don’t care about your bad day. They’re going to come up and they’re like, “I want you to pet me.” You know? And you’re like, “OK, but I’m feeling really mad right now, but I’m petting you,” and, man, they don’t know the amazing stuff they do for our vets who come through.

POWERS: It’s been a long journey for Jackson, going from battlefield to farmland. He served six tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, and he returned home with post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury. Getting care has been a challenge. Initially he was seeing a psychiatrist at the VA center in Tuskegee, Alabama. But, he says, he was told he had to wait six months between appointments. Last year he had a meltdown. He called the VA’s crisis hotline, and he says the earliest they could see him was in eight weeks. After a lot of pushing, they moved that up to two weeks, but Jackson says it shouldn’t have been that hard.

JACKSON: Every appointment that I got with them was because it was like, “No, I need to see you right now.” You know? I had to push it and it was like I’m fighting, fighting, fighting. You know what, man? You get sick and tired of fighting. Why am I fighting for care? Well, guess what happened within that six months. Guess what happened. I come back, and I find I got diabetes. So, I’m taking all these medications. You know, there’s nobody watching Jon Jackson.

POWERS: Well, that’s not entirely true anymore…

[ROOSTER CROWS.]

POWERS: Instead of waiting for care, Jackson wanted more immediate attention. So, he moved to Milledgeville with his family, started going to a nearby VA facility in Dublin, where he says care is better, and he started a farm. It’s called Comfort Farms, named after a friend of Jackson's who was killed in action in Afghanistan. Comfort Farms is ripe with everything from okra and tomatoes to chickens and pigs.

[PIGS GRUNTING]

POWERS: For Jackson, farming fits like a glove, as he readjusts to civilian life with the scars of war.

JACKSON: You know, farming is chaos, and I like chaos. So, it’s just like one of those things where I’m constantly here, struggling against Mother Nature, struggling against pests, but, you know, when you win, you get those small battles, those small victories.

Veterans and volunteers gather to celebrate a September 2016 donation to Stag Vets, the nonprofit that runs Comfort Farms. (Photo: Comfort Farms)

POWERS: Veterans coming back from conflict often struggle with transition to civilian life. They have higher rates of depression and suicide, and they’re more likely to be unemployed. Jackson hopes to change that by introducing more vets to farming. He’s got a USDA grant to travel the state, training vets on agriculture. 150 vets and their families have visited his farm so far this year. One of them is Thomas Scott Kennedy, who also suffers from PTSD.

[SOUND OF CAR DRIVING]

POWERS: I’m in his car as we ride to the VA center in Dublin, where he has three appointments that were scheduled a little less than a month ago. VA data released in August shows on average 92 percent of vets with appointments are waiting 30 days or less for care. Kennedy says, working on the Comfort Farms helps him while he waits.

KENNEDY: You’re dealing with the VA on a every other week, every once a month type of situation where in the farming environment with Jon and the farm, every morning you’re up doing something. You’re taking care of the animals. You’re looking outward. You’re not looking inward. That’s helpful.

POWERS: That’s a huge leap from where he was a few months ago. During Memorial Day, he charged head-first into the side of his house. His family watched in horror as blood ran down his head. His wife applied for a protective order. A judge ordered Kennedy to stay away from his family for a year.

KENNEDY: And that basically sent me over the edge again, and that’s when I went into the woods and starting taking medications in order to end my life.

NEWS ANCHOR: Investigators in Oglethorpe County are looking for a missing Marine veteran who they say could be suicidal, 49-year-old Thomas Scott Kennedy last seen June 2nd. He drives a silver 2004 Toyota Tundra…

POWERS: A friend found Kennedy and connected him with Jon Jackson. Now Kennedy lives on Jackson’s property, on one condition – that he helps on the farm. Melinda Paige is a counselor in Atlanta. She works with people suffering from PTSD, and she says having them work together - like on a farm - can help stimulate brain activity.

PAIGE: I believe they do better when they have a shared mission. They’re extremely resilient, strong individuals, and since PTSD is a medical condition, it’s a treatable medical condition, it means their brain is simply injured by the high stress that they’ve lived with and can be healed.

Reporter Sean Powers talks with veteran Thomas Scott Kennedy as they head to the Carl Vinson Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Dublin, Georgia. (Photo: Sean Powers)

POWERS: Nearly half of veterans returning from Iraq & Afghanistan are from rural areas. But the USDA says very few go into farming. The director of the Dublin VA sees her center’s location in rural Georgia as an opportunity. Maryalice Morro is talking with the state’s Department of Agriculture about growing fresh produce on-site that can be used in her center’s cafeteria.

MORRO: We house approximately 115 veterans in our domiciliary, mental health rehabilitation program that helps veterans with homelessness, PTSD, substance abuse and/or a combination of those get back on their feet. They’re usually here for a period of 60 to 90 days, so it would be a great way to teach them new skills or give them something to do while they’re here. Could be therapeutic.

POWERS: There are still a lot of unknowns about the benefits of farming for veterans. But it may take off as the nation’s farmers get older, and the VA searches for ways to improve care while cutting down on wait times.

For Living on Earth, I’m Sean Powers in Atlanta.

Related links:

- More about Comfort Farms

- The nonprofit Stag Vets uses farming in part to promote veterans’ mental health

- National Center for PTSD

- About reporter Sean Powers

[MUSIC: Jo Ann Smith, “Rhythm Of the Rain,” Autoharp Legacy, John Claude Gummoe, Arts In the Woods]

From Orange To Green

Crews with Baltimore Tree Trust plant trees on the sidewalks in front of rowhouses (Photo: Baltimore Tree Trust)

CURWOOD: From life on the farm, to life in the gritty inner city. In the predominantly black and low-income neighborhoods of Baltimore, violent crime is all too commonplace along bleak asphalt and concrete streets. But an effort to green these neighborhoods is also uplifting residents by putting them to work planting trees. In particular, nonprofits are giving former inmates and would-be drug dealers the opportunity to take ownership of their home turf while earning a living wage.

Among them is Alex Smith, who spent 15 years in prison, but has turned over the proverbial new leaf and now works for the Baltimore Tree Trust. Alex, welcome to Living on Earth.

SMITH: Hey, how are you doing?

CURWOOD: Good. Hey first, tell me what you do as a staff member of the Baltimore Tree Trust?

SMITH: Well, my official title is Field Operations and Outreach. Essentially, I'm a foreman, and I work with fellas and ladies who come from rough backgrounds, and we go out and plant trees all over Baltimore.

CURWOOD: Even when it's hot?

SMITH: Even when it's hot. It's hot today, and I just finished planting some Zelkovas.

CURWOOD: Zelkovas. What are those?

SMITH: They are a good, hardy, street tree. They are one of the most popular trees that we plant.

CURWOOD: Alex, I understand that you were in prison for some 15 years or so before joining the Tree Trust. What was that like and how did you make the most of your time behind bars?

SMITH: I don't really know how to explain prison to anybody who hasn't been there. I can sum it up in two words: It sucks.

CURWOOD: Well, how did you make the most of your time behind bars?

SMITH: Reading, exercising, studying. Behind bars is actually where I learned horticulture and started working with plants. I'm a certified Master Gardener due to Merlin Cooperative extension program.

CURWOOD: And what inspired you to get into working with plants, working with gardens?

Alex Smith leads the field operations and outreach effort at Baltimore Tree Trust. (Photo: Baltimore Tree Trust)

SMITH: Well, they had a little horticulture program. It was a guy that came from Frostburg University, Dr. Wayne Yoder. He would come there and teach about plants, but it was not like we could put it into practical application. We were just learning about it. But when we approached the staff about a garden, this idea started growing that we could actually transform the grounds and that we could use what we were learning in the classroom inside of the prison.

CURWOOD: How did you feel once you started that horticultural program, there in prison, that you were going to green the place?

SMITH: It was definitely a good feeling. It was a feeling that if you know, one, that we were even paid attention to. You know, a lot of times I've written letters to different organizations, and they went unanswered or they were simply returned, so, for us to actually have somebody starting to pay attention to us, that exciting to begin with. It was a foundation that actually helped us out, the TKF Foundation. They were already doing meditation gardens around the city. Their only requirement was that we somewhere put a meditational Peace Garden. So we did that right out in front of the chapel.

CURWOOD: At the prison.

SMITH: Yes, in western Maryland, WCI.

CURWOOD: So you build these gardens in the prison, and then you get out. How did you find your job with the Baltimore Tree Trust?

Baltimore Tree Trust cares for the trees they plant for the first two years (Photo: Baltimore Tree Trust)

SMITH: Well, I was working a couple of jobs. At the time I was working construction, but you know in construction that you have a lot of downtime because of weather or what have you, so what I was doing was landscaping on the side. Someone suggested I buy a pick-up, that I shouldn't let the landscaping skill just sit on the shelf, so I took their advice, and because I volunteer at the Center for Urban Families, I would show some of the people around there, some of the stuff that I could do. Part of it was in hopes to get a couple of new clients, but I was also proud of my work. So, I guess Dan walked in and talked to one of the career counselors. Dan Miller, he's the Executive Director of the Baltimore Tree Trust, my boss, he walked in looking for somebody who could work with the Baltimore Tree Trust, and my name came up, and they said I know someone who does that work.

CURWOOD: Now, how do you recruit other people, who've had similar experiences, spent time in jail? How do you recruit them to help you plant trees?

SMITH: Well, everywhere I go in Baltimore and I'm asked, “Are you hiring?” So it's pretty easy when I'm in the Baltimore Tree Trust truck, and I have a vest on, and I'm out working. It's pretty easy to get people who say they're interested in jobs, but mostly I come to the Center for Urban Families and get people that have come through STRIVE program.

CURWOOD: STRIVE. Tell me more about STRIVE.

SMITH: STRIVE is an employment readiness program which basically sharpens up or refreshes people’s soft skills, and it helps them not only get jobs but keep jobs.

CURWOOD: Alex, why plant trees in Baltimore?

Baltimore’s economically-depressed neighborhoods largely lack trees (Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

SMITH: One, it's for beautification. You know, you put trees in a block, it changes the whole environment. It's not just concrete and asphalt and brick, but two, it definitely helps our environment. They trap rainwater and the bad stuff that it doesn't get filled by the tree pits and the trees and roots themselves, all the stuff goes right into the Chesapeake Bay. But beautification and how it changes what people see when they look out their window, that's the most important part to me.

CURWOOD: Is there a place with trees in Baltimore that's a particular favorite of yours?

SMITH: Well, it's a place that I haven't planted, but it's a small street near York Road in Baltimore that has full grown trees that just canopy the whole street, like it reminds you of maybe what the block looked like some 56 years ago. Pretty amazing to see these trees. Until I started working for the Baltimore Tree Trust I never really paid attention to them. That's what I envision when I'm out there planting a tree, that one day the tree that I plant will look like that. And we plant some of the same varieties, so, you know, I'll be checking it out in 30 years, to see.

CURWOOD: How do people in the community respond to the work that you're doing now, planting trees?

SMITH: For the most part, we definitely have community support. It is not just the people who are seeking employment or are interested in that way. It is just from normal, everyday people who just like to see trees, like to see people working, but we do have those people who we have to convince that planting trees in their neighborhood, planting trees in front of their house is a good thing.

There's a lot of myths about trees bring rats, trees strangle pipes. That's like the number one issue that we get, and some people just they just don't want them because of bugs, mosquitoes. We get all kind of things. When we are out in the community we are definitely armed with information and sometimes, you know, even if you show people, they still don't want the tree.

CURWOOD: What kind of ownership, what kind of responsibility for the trees do people in neighborhoods take, once you plant the tree?

SMITH: Well, Baltimore Tree Trust, we give them a bucket that has a lot of pointers on it about trees. We pass out flyers. Part of my job is to do outreach. So, it's not just outreach with the fellas that I hire to help me plant these trees, but it’s outreach in the community to dispel some of the myths about the trees and to teach people how to care for them. But we also maintain the trees for two years after we plant them. So, people in the neighborhood, they see us maintaining the trees and pruning the trees and making sure that we care for the tree, so any chance that I can, I'm always giving people advice and giving them pointers and tips on how to take care of the tree.

Some people have actually taken ownership of the trees, you know, “That's my tree.” Even some neighbors squabble over whose tree it is. For the people who care about the neighborhood and care about the way the neighborhood looks, we get a pretty good response from those people.

CURWOOD: Now Alex, many neighborhoods you work in are mostly African-American, but the Baltimore Tree Trust is mostly a white institution. How do people respond to that?

SMITH: I've never had anybody directly have a problem with it. I do know that in Baltimore City people do have a feeling that there's a lot of white organizations that come in the city without asking, do people want the services or products and things like that, and they just shove them down people's throats. That's what people believe in the neighborhood for the most part.

I would like to think that, because I was presented this opportunity, it is my chance to try to change that, change that perception. So, what I'd do is, I go and knock on people's doors, and I say, “Hey, a tree is coming.” I tell them the laws concerning the tree, but I also ask their opinion about it, and sometimes, if they are adamantly against the tree, we don't plant it. I definitely make sure that the community in which we're working in are considered. It’s not that they will open the door one day and see 20 people standing in front of house, planting trees.

CURWOOD: Imagine some people might be worried about gentrification, that planting trees could raise property values, and end up pushing out the very people who are supposed to benefit.

SMITH: That's a definite concern, and a lot of people do believe that. They do believe that the trees didn't come until the property values starting raising in some of the neighborhoods that I worked in, and nobody cared about the sidewalks or the streets until people from outside started investing and remodeling some of the bigger homes in the neighborhood. I really don't know the answer to that, but I know that the Baltimore Tree Trust, we plant trees for everybody.

And I don't see any bulldozers or tanks pushing people out of the neighborhood. Even though I can say that, you know, when you raise prices to a certain level you will squeeze out certain buyers, you know, and that's an issue that is way above Tree Trust. That's an issue that should concern everybody, everybody that is looking to keep Baltimore a city that welcomes everybody. That’s something that we all have to work together on.

The Western Correctional Institution in Maryland, where Alex Smith served 15 years. (Photo: Jon Dawson, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, Alex, this has worked well for you, helped you turn your life around. What about other prisoners and former prisoners, people getting out of jail, trying to establish themselves in communities again?

SMITH: Well, I hope that I'm not an anomaly. I would hope that eventually this catches on because every day that I'm out in the street I see opportunity. You know, while I'm planting trees, I see the tree pits that aren't being taken care of. I see the trees that have been planted years ago that aren't being cared for. I see the litter that’s in the tree pits. All those are unemployment opportunities. You know, if the government, the communities, if they're just a little creative and can see that the opportunities that I see while I'm out there in the street, I think that it definitely can work for other people.

CURWOOD: Before you go, Alex, tell me about your vision for the future of Baltimore's environment, including the trees.

SMITH: My vision for Baltimore and myself is that I learn more about the trees. I learn more about how they impact our environment. I learn more about how I can help other people. I mean, I'm a servant for my community, and I feel like I'm blessed to be given this opportunity, so every day that I go out in the street is, for me, it's an opportunity to give back.

You know, I took away so much from the streets and from the neighborhoods. I was the bad element at one time. I just hope that I can have an impact, and I can help other people the way I've been helped.

CURWOOD: Alex Smith leads field operations and outreach for the Baltimore Tree Trust. Alex, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SMITH: No problem. Any time.

Related links:

- Read Rona Kobell’s story for the Chesapeake Bay Journal about ex-cons in green jobs

- Baltimore Tree Trust

- About the gentrification of Baltimore

- About Alex Smith

[MUSIC: Childsplay featuring Matt Glaser, Joyce Andersen, Dave Langford, & Ralph Gordon, “Tristesse,” The Great Waltz, Claudio Buchwald, Childsplay Music]

CURWOOD: Coming up, talking tyrannosaurs. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Johnny Otis, “Harlem Nocturne” on “Harlem Nocturne” single, written by Earle Hagen and Dick Rogers, Excelsior Records]

Finding New Tyrannosaurs

David Hone excavates a tyrannosaur fossil in Xinjiang, China. Opaque as they may seem, bones provide an incredible amount of information for those who know how to decipher them. (Photo: courtesy of David Hone)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

The name means Tyrant Lizard King, and in 1905 the New York Times called Tyrannosaurus Rex the “absolute warlord of the earth.”

T. Rex fossils were first discovered in 1874, and now the group includes some 29 different species, with a new one identified just about every year these days. The Tyrannosaur family was extremely successful during its 100 million years on Earth. They were active on four of the present continents, and fossils have been found in Britain, where David Hone now studies them at Queen Mary University of London. His book, The Tyrannosaur Chronicles, details the anatomy, evolution, and ecology of these fearsome carnivores.

We called him up, but before we talked Tyrannosaurs we challenged David Hone to name as many of the family as he could in 15 seconds. Go!

HONE: Oh boy. Guanlong, Dilong, Yutyrannus, Lythronax, Alioramus, Tyrannosaurus, Tarbosaurus, Daspletosaurus, Albertosaurus, Gorgosaurus, um, Bistahieversor, Qianzhousaurus, uh… [BELL RINGS] Damn it. I know there‚ a couple more, and I’m struggling now.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] So, David, this was a widespread family with lots of variety?

HONE: They were really quite diverse. So the first few species that we have around 165 million years ago were about the size of something like a Labrador, and actually some of the early species of Tyrannosaur also had these big elaborate bony crests on their heads so actually had a fairly different profile, and they didn't have the giant heads, and they didn't have the little arms or things like Tyrannosaurus and the very last of the Tyrannosaurs.

CURWOOD: In your book, you say, "As I'm writing this, there are likely to be more species identified, and my book will be out of date even before it hits the bookstore."

HONE: That's already happened. So, in February, so the book was already at the publishers, a new Tyrannosaur was named from Asia. And, actually, as I was writing the book, three new species were added. I wrote that line of, "This book is going to be out of date by the time this book is published," and then I kept having to edit that line because it was already getting out of date faster than I could update the book. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: Now, you're a scientist, so this is a totally unfair question, but what's the simple explanation of what makes a Tyrannosaur a Tyrannosaur?

David Hone’s new book, The Tyrannosaur Chronicles, details the anatomy, evolution, and ecology of the world’s most iconic dinosaurs. (Photo: courtesy of David Hone)

HONE: Happily, these are one of the rare groups where there’s a fairly simple explanation for this. The very front teeth in the jaw have this very odd profile. They have a flat back pointed into the mouth and a very round front pushing out of the front, and this is actually a feeding adaptation. And the other thing they have are the bones called, “the nasals.” There's two bones. You have one on the left and one on the right. Basically all animals have this. But in the Tyrannosaurs they're fused together into one big block.

CURWOOD: Ah, the teeth are, “the better to eat you with,” I gather, huh?

HONE: Well, specifically for feeding, so, they have these giant, kind of robust bone-crunching, killing teeth down the sides of the jaw, but at the front they have yeah these kind of flat, blunt, little basically scraping teeth. The best analogy I can give is, take a cookie like an Oreo, peel off one biscuit and how do you get the cream off? And everyone puts it in their mouth and pulls it forward and scrapes the cream off on their teeth. And this is how the Tyrannosaurs were feeding, and we know this actually because we have the bones that they were feeding on, and they leave exactly these marks. You see a whole bunch of very blunt but deep grooves in the bone, pulled in a straight line together. They’re basically scraping the muscle off the bone with these odd little teeth.

CURWOOD: So, what did these animals look like, and how do we know this?

HONE: Well, the big ones were big. [LAUGHS.] They walked on their back legs. I mean, the fact they've got tiny arms is a pretty big giveaway. We've also got footprints for these animals, so we can see that they were definitely walking around on their back legs. We also don't see any tail traces, so we know the tail is held up off the ground, and Tyrannosaurs probably had feathers.

There's an early thing from China called Dilong, which has some patches of feathers preserved alongside it, and then there is a much larger Tyrannosaur, seven or eight meters long, from China, called Yutyrannus, and Yutyrannus basically is preserved with feathers from the tip of its nose to the tip of its tail. This thing was covered, and therefore the obvious inference is that the other Tyrannosaurs were too. We just simply haven't found the feathers yet. And that's not a big surprise, feathers do not preserve very often.

CURWOOD: So, in your book you discuss trying to figure out the color of these things. How would you do that?

The slow process of unearthing a tyrannosaur skull, shown clockwise from top left. This one belongs to a Gorgosaurus, a genus that lived in western North America between 76.6 and 75.1 million years ago. (Photo: courtesy of David Hone)

HONE: The short version is, at least part of what makes up the color in feathers - and indeed it does actually inherit some other things as well – are these tiny little packages called melanosomes, and they basically contain these color pigments.

Imagine if you went to a DIY store or something like a hardware store, and all the paint was sold in different shaped tins, and the tins actually correspond to the colors that are in them. So, black always comes in a long, thin tin. Blue always comes in square tin, and yellow always comes in a triangular tin or something like this.

As it happens, the way the melanosomes are laid down, different pigments correspond to different shapes of package. So actually you don't need to see the actual color to know what color was in there, as long as you've got the shape.

There are some huge limitations to this. So, for example, we can only do general shades. So, red basically means anything from kind of, bright orange all the way down to dark brown. Then, there are some complications because you can actually, then, change the colors, often quite dramatically by how you orientate the tins relative to each other, and that actually that information is probably lost during the decay. So we never see blue, for example, because blue is a color which is basically built on structure, not on melanosomes.

CURWOOD: So, with all these feathers, I'm wondering, what does science have in the way of DNA from Tyrannosaurs?

HONE: Nothing at the moment, unfortunately. Maybe, maybe, maybe one day we'll find something like that, but even if we do you'd be talking about tiny fragments of bits. You know, you'd be lucky to able to go, yes, this is probably a reptile, let alone this has something unique about it which is Tyrannosaurian, so, don't get your hopes up for a Jurassic Park sequel any time soon.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about the life of the Tyrannosaurs. How close were they to the top of the food chain?

HONE: The basic life of them, as indeed for most animals, was short because, as with animals in the modern world, you know, most things don't survive past their first year. In terms of what they're doing ecologically, of course, it varies enormously.

The first few Tyrannosaurus were two to three meters long, forty, fifty kilos. These were pretty small carnivores in their ecosystem, the equivalent of something like a fox or jackal or badger now. So they were making their way in the world as it were, but there were lots of big threats out there to them.

When you get through to the later giants, things like Tyrannosaurus and in Asia things like Tarbosaurus, they are the biggest carnivores out there. In fact, they are the biggest carnivores on Earth at this point, somewhere in the range of five to seven metric tons. These are seriously big animals, and the next biggest carnivore is like twenty kilos compared to a five, seven-ton monster. This is an enormously big gap in size. You would expect to have anything from about three to six or even seven big carnivores. And, frankly, I have no idea why. I have yet to come across anyone who has any idea why.

The obvious conclusion is that it's the younger animals that are kind of filling in those ecological niches. A half-grown Tyrannosaurus is seven, eight meters long, weighs a couple tons. Okay, that's filled that midsize carnivore niche. That's an explanation, but it doesn't explain why we don't see that for some of the earlier ecosystems, so it's very, very odd.

CURWOOD: Well, and science has to have more mysteries to solve, doesn't it, huh? So how fearsome were they, really? I mean, what did they have in the way of, you know, cute and cuddly ones as well?

Relative to its head, this T. rex’s eye sockets may seem small. In fact, they are the largest of any known terrestrial animal of all time. That means that T. rex, like its tyrannosaur relatives, had excellent eyesight – possibly better than any other land animal ever. (Photo: Scott Robert Anselmo, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 3.0)

HONE: Well, the small ones would've been fairly cute and cuddly, but they’d probably have taken your arm off if you were standing in front of them. And, of course, the juveniles, a hatchling was actually, was really pretty small. I mean, a hatchling Tyrannosaurus might be less than a meter long. So, this is an animal that has to get from under a meter to over twelve meters, to become up a full-sized adult. So, that's a colossal amount of growth, and so actually, yeah, for a normal population there would have been lots of baby and young Tyrannosaurs knocking around.

And, bear in mind, a young Tyrannosaurus can be an animal seven meters long and weighs a ton, but it's still barely an adolescent by human standards.

CURWOOD: How do they find their food? The big ones, I mean, obviously everybody knows they're coming.

HONE: They may not need to worry about whether things can see them coming because what the big Tyrannosaurs were built for was actually long-distance running. They were pretty quick. They couldn't run in one sense, the actual biomechanical definition of running. They were probably not getting both legs off the ground at once. What they had was actually, what’s effectively a very quick walk. But when you're that big with legs that long, you still cover a lot of ground very quickly. So actually what they may well be doing is, effectively, coming over the horizon approach. You don't care if the prey sees you coming. You just run at the herd or the group or the individual that you selected and try and close the gap faster than they can outpace you. They might be faster in the short term, but as long as you can keep them in view, you will go for longer.

The second solution, which I actually posit in the book, and don't think has been suggested before -- This is one of the really great things about writing a popular science book rather than a piece of science literature -- You can speculate a bit more freely. There is an obvious solution to this, which is, Be nocturnal. These animals four, five meters high to the top of the head. There probably is no cover they can hide in, but these are animals that we know that had exceptional eyesight. And one of the big correlates of being nocturnal is having exceptional eyesight. This would actually probably offset part of the problem of not being able to hide when you're that big.

I freely admit, this is complete speculation, but I think it fits the limited things that we know about.

CURWOOD: So how do you know that they had such great eyesight?

HONE: Actually the very short version is that they have enormous eye-sockets. One thing we do know from very careful studies of mammals and birds in particular, owls actually serves directly relevant. Basically the bigger the eyeball you can physically fit in the skull, the better it is at taking in light and details. And people have said the Tyrannosauruses have got little eyes, and compared to the size of its skull, it does. They look small but it's not relative size that's important, it's absolute size, and they are absolutely enormous. In fact, the eyes of Tyrannosaurus when measured, or at least the eye-socket are the largest of any terrestrial animal of all time. So, in fact, this animal had, in some way, shape or form the best eyesight of any animal on land that we know of, of all time.

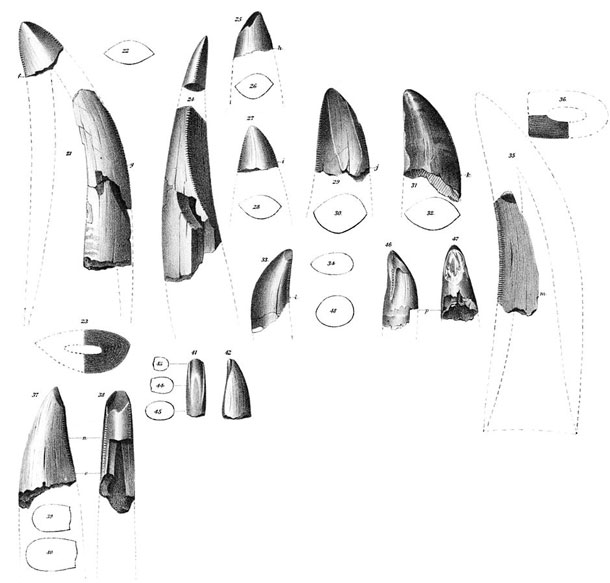

Tyrannosaurs’ unique scraping teeth – round at the front and flat at the back – are one characteristic that tells paleontologists they’ve dug up a tyrannosaur. (Photo: Joseph Leidy, Wikimedia Commons CC)

CURWOOD: David, I have to ask you this. On the big Tyrannosaurus, T-Rex, how do they reproduce? I mean, you’d think sex would be kind of risky with all those teeth?

HONE: [LAUGHS] “Carefully,” is the obvious answer. In terms of actual physical congress, let's say, actually is quite awkward because they are these big bipeds. They are big heavy animals falling over is actually quite big deal for them, and yet you need to get relevant parts together, and that's quite difficult, since it under the base of this big and actually very muscular tail. The obvious conclusion is that the male had something – and I'm not being prurient in this term – an intermittent organ in other words something that poked out or could be poked out. This is not unique to mammals. Actually lots of birds, in particular ducks. You may not want to Google this from your office, but I can highly recommend looking up some of the biology of duck reproduction, and that's actually probably the best way that you could get a male and female, seven ton carnivores with little arms that might fall over, together, but I have to add to that, of course we don't actually know for sure.

CURWOOD: There's a fascinating part of your book where you talk about Tyrannosauruses functioning as part of a larger ecosystem. Describe for me what these ancient ecosystems might have looked like and the role that the Tyrannosaurus played.

HONE: A Tyrannosaurus would actually have lived in an environment, which would look a lot alike it did today. We had grasses by this time. We had big conifer forests. We had big open plains. So, actually some of the big forests in North America, you know, it would recognize a lot of those plants.

More interesting one is Tarbosaurus. So this is kind of the Asian equivalent, if you'd like, which lived in Mongolia in Northern China. And at that time, actually much of the Gobi Desert is a desert now. That's what the environment looked like sixty-five, seventy million years ago. So this is a very, very different environment for a very similar animal.

CURWOOD: So what do you wish people knew about dinosaurs, and is there a dinosaur myth you can bust for us?

David Hone, Lecturer in Zoology at Queen Mary University of London, regularly blogs about dinosaurs in addition to his own research. (Photo: courtesy of David Hone)

HONE: One thing that comes back again and again is, “You can't know that, you clearly made that up.” I've done stuff online. I’ve written articles, and I do Q&As on websites and stuff. And what they see is, I go, “Well, actually we do know what color they were, sort of, and we know that they can run at the speed, and we know that they were bad at turning or we know they fed with their front teeth.”

“How can you possibly know that?”

Well, they have this unique tooth shape that suggests that they are doing something with it. We have bite marks on bones that match tooth shape. And then they go,”Oh!” And it's like, “Right.”

Um, dig into it. See what it is that we know and how that we know this because research is doing some phenomenally clever and impressive stuff, and there are some incredible specimens which give us these details.

In terms of busting a dinosaur myth, it's the one which is almost at a tipping point because I now increasingly come across people who go, “I knew that,” and they're not that impressed, but remember that the dinosaurs aren't extinct. Birds are dinosaurs. Birds are the direct descendants of dinosaurs. Evolutionarily, indeed taxonomically, they are dinosaurs.

CURWOOD: What's left in terms of the Tyrannosaurs? Are they all extinct?

HONE: Yes, so Tyrannosaurus did go extinct in the great extinction 65 million years ago. Tyrannosaurus is actually one of the last non-avian dinosaurs that we know of. You know, that's the guy who would stand on a hilltop and seen the meteor coming. So the birds branched off from a group of dinosaurs, actually very close to the Velociraptors. There was a little type of branching event and one group went on to produce stuff like Velociraptor and another group went on to produce the birds. So birds go back to about 150 million years ago.

CURWOOD: David Hone is a lecturer in zoology at Queen Mary University of London. His new book is called "The Tyrannosaur Chronicles.” Thanks so much for taking time with us today, David.

HONE: Thank you for having me on.

Related links:

- David Hone’s website

- “Lost Worlds,” David’s dinosaur blog hosted by the Guardian

- David’s personal dinosaur blog, “Archosaur Musings”

- A new tyrannosaur species, discovered as the Tyrannosaur Chronicles went to print

- The Tyrannosaur Chronicles

[MUSIC: Dr. John, “I’m an Old Cow Hand” on Mercernary, Johnny Mercer, Parlophone Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Matt Hoisch, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Olivia Reardon, Rebecca Redelmeier, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Jake Rego engineered our show, with help from Zack Ronald. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth