Finding New Tyrannosaurs

Air Date: Week of August 11, 2017

David Hone excavates a tyrannosaur fossil in Xinjiang, China. Opaque as they may seem, bones provide an incredible amount of information for those who know how to decipher them. (Photo: courtesy of David Hone)

Sixty-five million years ago, T. Rex was the biggest carnivore on Earth, and to this day it looms large in our imaginations. But science now knows this iconic tyrant lizard was but one of more than two dozen species of tyrannosaur, a diverse family that lasted 100 million years and came in many shapes and sizes. David Hone, author of The Tyrannosaur Chronicles, tells host Steve Curwood what we know about these extraordinary creatures.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

The name means Tyrant Lizard King, and in 1905 the New York Times called Tyrannosaurus Rex the “absolute warlord of the earth.”

T. Rex fossils were first discovered in 1874, and now the group includes some 29 different species, with a new one identified just about every year these days. The Tyrannosaur family was extremely successful during its 100 million years on Earth. They were active on four of the present continents, and fossils have been found in Britain, where David Hone now studies them at Queen Mary University of London. His book, The Tyrannosaur Chronicles, details the anatomy, evolution, and ecology of these fearsome carnivores.

We called him up, but before we talked Tyrannosaurs we challenged David Hone to name as many of the family as he could in 15 seconds. Go!

HONE: Oh boy. Guanlong, Dilong, Yutyrannus, Lythronax, Alioramus, Tyrannosaurus, Tarbosaurus, Daspletosaurus, Albertosaurus, Gorgosaurus, um, Bistahieversor, Qianzhousaurus, uh… [BELL RINGS] Damn it. I know there‚ a couple more, and I’m struggling now.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] So, David, this was a widespread family with lots of variety?

HONE: They were really quite diverse. So the first few species that we have around 165 million years ago were about the size of something like a Labrador, and actually some of the early species of Tyrannosaur also had these big elaborate bony crests on their heads so actually had a fairly different profile, and they didn't have the giant heads, and they didn't have the little arms or things like Tyrannosaurus and the very last of the Tyrannosaurs.

CURWOOD: In your book, you say, "As I'm writing this, there are likely to be more species identified, and my book will be out of date even before it hits the bookstore."

HONE: That's already happened. So, in February, so the book was already at the publishers, a new Tyrannosaur was named from Asia. And, actually, as I was writing the book, three new species were added. I wrote that line of, "This book is going to be out of date by the time this book is published," and then I kept having to edit that line because it was already getting out of date faster than I could update the book. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: Now, you're a scientist, so this is a totally unfair question, but what's the simple explanation of what makes a Tyrannosaur a Tyrannosaur?

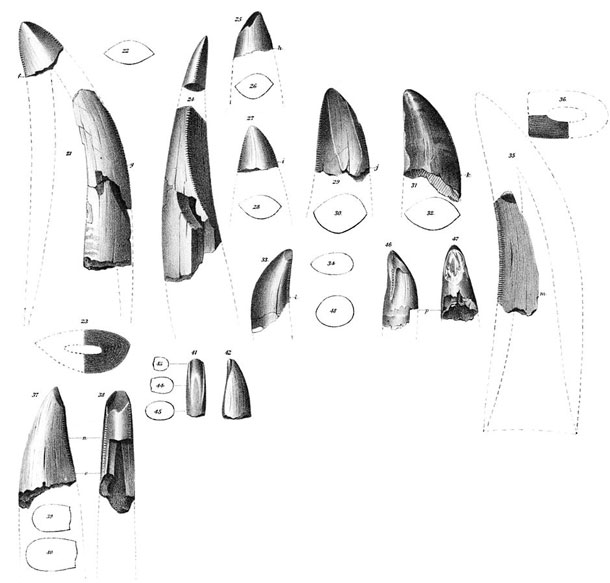

David Hone’s new book, The Tyrannosaur Chronicles, details the anatomy, evolution, and ecology of the world’s most iconic dinosaurs. (Photo: courtesy of David Hone)

HONE: Happily, these are one of the rare groups where there’s a fairly simple explanation for this. The very front teeth in the jaw have this very odd profile. They have a flat back pointed into the mouth and a very round front pushing out of the front, and this is actually a feeding adaptation. And the other thing they have are the bones called, “the nasals.” There's two bones. You have one on the left and one on the right. Basically all animals have this. But in the Tyrannosaurs they're fused together into one big block.

CURWOOD: Ah, the teeth are, “the better to eat you with,” I gather, huh?

HONE: Well, specifically for feeding, so, they have these giant, kind of robust bone-crunching, killing teeth down the sides of the jaw, but at the front they have yeah these kind of flat, blunt, little basically scraping teeth. The best analogy I can give is, take a cookie like an Oreo, peel off one biscuit and how do you get the cream off? And everyone puts it in their mouth and pulls it forward and scrapes the cream off on their teeth. And this is how the Tyrannosaurs were feeding, and we know this actually because we have the bones that they were feeding on, and they leave exactly these marks. You see a whole bunch of very blunt but deep grooves in the bone, pulled in a straight line together. They’re basically scraping the muscle off the bone with these odd little teeth.

CURWOOD: So, what did these animals look like, and how do we know this?

HONE: Well, the big ones were big. [LAUGHS.] They walked on their back legs. I mean, the fact they've got tiny arms is a pretty big giveaway. We've also got footprints for these animals, so we can see that they were definitely walking around on their back legs. We also don't see any tail traces, so we know the tail is held up off the ground, and Tyrannosaurs probably had feathers.

There's an early thing from China called Dilong, which has some patches of feathers preserved alongside it, and then there is a much larger Tyrannosaur, seven or eight meters long, from China, called Yutyrannus, and Yutyrannus basically is preserved with feathers from the tip of its nose to the tip of its tail. This thing was covered, and therefore the obvious inference is that the other Tyrannosaurs were too. We just simply haven't found the feathers yet. And that's not a big surprise, feathers do not preserve very often.

CURWOOD: So, in your book you discuss trying to figure out the color of these things. How would you do that?

The slow process of unearthing a tyrannosaur skull, shown clockwise from top left. This one belongs to a Gorgosaurus, a genus that lived in western North America between 76.6 and 75.1 million years ago. (Photo: courtesy of David Hone)

HONE: The short version is, at least part of what makes up the color in feathers - and indeed it does actually inherit some other things as well – are these tiny little packages called melanosomes, and they basically contain these color pigments.

Imagine if you went to a DIY store or something like a hardware store, and all the paint was sold in different shaped tins, and the tins actually correspond to the colors that are in them. So, black always comes in a long, thin tin. Blue always comes in square tin, and yellow always comes in a triangular tin or something like this.

As it happens, the way the melanosomes are laid down, different pigments correspond to different shapes of package. So actually you don't need to see the actual color to know what color was in there, as long as you've got the shape.

There are some huge limitations to this. So, for example, we can only do general shades. So, red basically means anything from kind of, bright orange all the way down to dark brown. Then, there are some complications because you can actually, then, change the colors, often quite dramatically by how you orientate the tins relative to each other, and that actually that information is probably lost during the decay. So we never see blue, for example, because blue is a color which is basically built on structure, not on melanosomes.

CURWOOD: So, with all these feathers, I'm wondering, what does science have in the way of DNA from Tyrannosaurs?

HONE: Nothing at the moment, unfortunately. Maybe, maybe, maybe one day we'll find something like that, but even if we do you'd be talking about tiny fragments of bits. You know, you'd be lucky to able to go, yes, this is probably a reptile, let alone this has something unique about it which is Tyrannosaurian, so, don't get your hopes up for a Jurassic Park sequel any time soon.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about the life of the Tyrannosaurs. How close were they to the top of the food chain?

HONE: The basic life of them, as indeed for most animals, was short because, as with animals in the modern world, you know, most things don't survive past their first year. In terms of what they're doing ecologically, of course, it varies enormously.

The first few Tyrannosaurus were two to three meters long, forty, fifty kilos. These were pretty small carnivores in their ecosystem, the equivalent of something like a fox or jackal or badger now. So they were making their way in the world as it were, but there were lots of big threats out there to them.

When you get through to the later giants, things like Tyrannosaurus and in Asia things like Tarbosaurus, they are the biggest carnivores out there. In fact, they are the biggest carnivores on Earth at this point, somewhere in the range of five to seven metric tons. These are seriously big animals, and the next biggest carnivore is like twenty kilos compared to a five, seven-ton monster. This is an enormously big gap in size. You would expect to have anything from about three to six or even seven big carnivores. And, frankly, I have no idea why. I have yet to come across anyone who has any idea why.

The obvious conclusion is that it's the younger animals that are kind of filling in those ecological niches. A half-grown Tyrannosaurus is seven, eight meters long, weighs a couple tons. Okay, that's filled that midsize carnivore niche. That's an explanation, but it doesn't explain why we don't see that for some of the earlier ecosystems, so it's very, very odd.

CURWOOD: Well, and science has to have more mysteries to solve, doesn't it, huh? So how fearsome were they, really? I mean, what did they have in the way of, you know, cute and cuddly ones as well?

Relative to its head, this T. rex’s eye sockets may seem small. In fact, they are the largest of any known terrestrial animal of all time. That means that T. rex, like its tyrannosaur relatives, had excellent eyesight – possibly better than any other land animal ever. (Photo: Scott Robert Anselmo, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 3.0)

HONE: Well, the small ones would've been fairly cute and cuddly, but they’d probably have taken your arm off if you were standing in front of them. And, of course, the juveniles, a hatchling was actually, was really pretty small. I mean, a hatchling Tyrannosaurus might be less than a meter long. So, this is an animal that has to get from under a meter to over twelve meters, to become up a full-sized adult. So, that's a colossal amount of growth, and so actually, yeah, for a normal population there would have been lots of baby and young Tyrannosaurs knocking around.

And, bear in mind, a young Tyrannosaurus can be an animal seven meters long and weighs a ton, but it's still barely an adolescent by human standards.

CURWOOD: How do they find their food? The big ones, I mean, obviously everybody knows they're coming.

HONE: They may not need to worry about whether things can see them coming because what the big Tyrannosaurs were built for was actually long-distance running. They were pretty quick. They couldn't run in one sense, the actual biomechanical definition of running. They were probably not getting both legs off the ground at once. What they had was actually, what’s effectively a very quick walk. But when you're that big with legs that long, you still cover a lot of ground very quickly. So actually what they may well be doing is, effectively, coming over the horizon approach. You don't care if the prey sees you coming. You just run at the herd or the group or the individual that you selected and try and close the gap faster than they can outpace you. They might be faster in the short term, but as long as you can keep them in view, you will go for longer.

The second solution, which I actually posit in the book, and don't think has been suggested before -- This is one of the really great things about writing a popular science book rather than a piece of science literature -- You can speculate a bit more freely. There is an obvious solution to this, which is, Be nocturnal. These animals four, five meters high to the top of the head. There probably is no cover they can hide in, but these are animals that we know that had exceptional eyesight. And one of the big correlates of being nocturnal is having exceptional eyesight. This would actually probably offset part of the problem of not being able to hide when you're that big.

I freely admit, this is complete speculation, but I think it fits the limited things that we know about.

CURWOOD: So how do you know that they had such great eyesight?

HONE: Actually the very short version is that they have enormous eye-sockets. One thing we do know from very careful studies of mammals and birds in particular, owls actually serves directly relevant. Basically the bigger the eyeball you can physically fit in the skull, the better it is at taking in light and details. And people have said the Tyrannosauruses have got little eyes, and compared to the size of its skull, it does. They look small but it's not relative size that's important, it's absolute size, and they are absolutely enormous. In fact, the eyes of Tyrannosaurus when measured, or at least the eye-socket are the largest of any terrestrial animal of all time. So, in fact, this animal had, in some way, shape or form the best eyesight of any animal on land that we know of, of all time.

Tyrannosaurs’ unique scraping teeth – round at the front and flat at the back – are one characteristic that tells paleontologists they’ve dug up a tyrannosaur. (Photo: Joseph Leidy, Wikimedia Commons CC)

CURWOOD: David, I have to ask you this. On the big Tyrannosaurus, T-Rex, how do they reproduce? I mean, you’d think sex would be kind of risky with all those teeth?

HONE: [LAUGHS] “Carefully,” is the obvious answer. In terms of actual physical congress, let's say, actually is quite awkward because they are these big bipeds. They are big heavy animals falling over is actually quite big deal for them, and yet you need to get relevant parts together, and that's quite difficult, since it under the base of this big and actually very muscular tail. The obvious conclusion is that the male had something – and I'm not being prurient in this term – an intermittent organ in other words something that poked out or could be poked out. This is not unique to mammals. Actually lots of birds, in particular ducks. You may not want to Google this from your office, but I can highly recommend looking up some of the biology of duck reproduction, and that's actually probably the best way that you could get a male and female, seven ton carnivores with little arms that might fall over, together, but I have to add to that, of course we don't actually know for sure.

CURWOOD: There's a fascinating part of your book where you talk about Tyrannosauruses functioning as part of a larger ecosystem. Describe for me what these ancient ecosystems might have looked like and the role that the Tyrannosaurus played.

HONE: A Tyrannosaurus would actually have lived in an environment, which would look a lot alike it did today. We had grasses by this time. We had big conifer forests. We had big open plains. So, actually some of the big forests in North America, you know, it would recognize a lot of those plants.

More interesting one is Tarbosaurus. So this is kind of the Asian equivalent, if you'd like, which lived in Mongolia in Northern China. And at that time, actually much of the Gobi Desert is a desert now. That's what the environment looked like sixty-five, seventy million years ago. So this is a very, very different environment for a very similar animal.

CURWOOD: So what do you wish people knew about dinosaurs, and is there a dinosaur myth you can bust for us?

David Hone, Lecturer in Zoology at Queen Mary University of London, regularly blogs about dinosaurs in addition to his own research. (Photo: courtesy of David Hone)

HONE: One thing that comes back again and again is, “You can't know that, you clearly made that up.” I've done stuff online. I’ve written articles, and I do Q&As on websites and stuff. And what they see is, I go, “Well, actually we do know what color they were, sort of, and we know that they can run at the speed, and we know that they were bad at turning or we know they fed with their front teeth.”

“How can you possibly know that?”

Well, they have this unique tooth shape that suggests that they are doing something with it. We have bite marks on bones that match tooth shape. And then they go,”Oh!” And it's like, “Right.”

Um, dig into it. See what it is that we know and how that we know this because research is doing some phenomenally clever and impressive stuff, and there are some incredible specimens which give us these details.

In terms of busting a dinosaur myth, it's the one which is almost at a tipping point because I now increasingly come across people who go, “I knew that,” and they're not that impressed, but remember that the dinosaurs aren't extinct. Birds are dinosaurs. Birds are the direct descendants of dinosaurs. Evolutionarily, indeed taxonomically, they are dinosaurs.

CURWOOD: What's left in terms of the Tyrannosaurs? Are they all extinct?

HONE: Yes, so Tyrannosaurus did go extinct in the great extinction 65 million years ago. Tyrannosaurus is actually one of the last non-avian dinosaurs that we know of. You know, that's the guy who would stand on a hilltop and seen the meteor coming. So the birds branched off from a group of dinosaurs, actually very close to the Velociraptors. There was a little type of branching event and one group went on to produce stuff like Velociraptor and another group went on to produce the birds. So birds go back to about 150 million years ago.

CURWOOD: David Hone is a lecturer in zoology at Queen Mary University of London. His new book is called "The Tyrannosaur Chronicles.” Thanks so much for taking time with us today, David.

HONE: Thank you for having me on.

Links

“Lost Worlds,” David’s dinosaur blog hosted by the Guardian

David’s personal dinosaur blog, “Archosaur Musings”

A new tyrannosaur species, discovered as the Tyrannosaur Chronicles went to print

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth