Fasting and Feasting: The Life of Visionary Food Writer Patience Gray

Air Date: Week of September 15, 2017

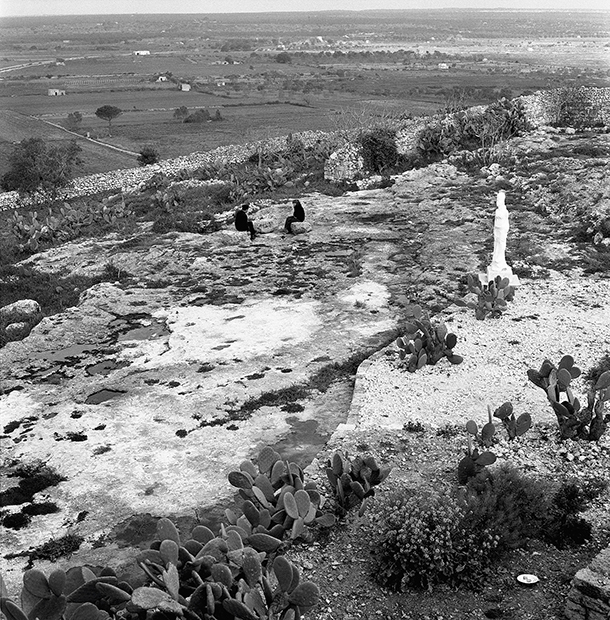

Patience at Spigolizzi in the mid 1990s. (Photo: Doris Schiuma)

Patience Gray’s pioneering European cookbook brought foreign tastes to the British home cook and her remarkable Honey From a Weed is still a key source of inspiration for popular food writers, yet she’s largely unknown today. A new biography, Fasting and Feasting, introduces her iconoclastic and meandering life, with artists, architects, and radicals in postwar London, and finally to the simplicity of living and cooking off the land at the remote heel of Italy’s boot. In conversation with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer, author Adam Federman shares Patience Gray’s story of lifelong artistic and culinary searching – and whets the appetite too.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. The early 1960s saw a revolution in ideas about food and home cooking. In the US, there was Julia Child, but a decade earlier austerity-weary Britons discovered adventurous, foreign tastes thanks to “A Book of Mediterranean Food” written by Elizabeth David. But she wasn’t the only culinary pioneer in the UK, and a new biography “Fasting and Feasting” introduces another, Patience Gray. She was an iconoclastic artist, writer, traveler and almost incidental cookbook writer, whose “Honey from a Weed” inspired cooks on both sides of the Atlantic. “Fasting and Feasting, the Life of Visionary Food Writer Patience Gray” is written by one-time bread baker and pastry chef Adam Federman, who spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

PALMER: Now, Adam Federman, what drew you to Patience Gray and her unusual but highly influential cookbook "Honey from a Weed"?

Patience and her childhood friend Betty Barnardo traveling in Germany in 1937. (Photo: courtesy of Miranda Armour-Brown)

FEDERMAN: There were many things. I mean, the interesting thing is that I had never heard of Patience until after she died in 2005 when I read an obituary in the Art of Eating food magazine, which described "Honey from a Weed" as one of the best books that will ever be written about food, and that struck me as a bit lofty, but I was, you know, equally intrigued to find out more about the book and the woman who wrote it, and then it turned out that my parents had a copy of "Honey from a Weed" on their bookcase that had been given to them years before, and I had never noticed. And as soon as I opened the book I was really swept away by the prose and the world that Patience described.

PALMER: What was it about the writing that particularly took you?

FEDERMAN: It engages you from the first page, and she has a remarkably vivid way of describing the world that she and her partner Norman lived in. But it was also her approach to food and cooking, and there's a section from the introduction that I think captures that quite well.

PALMER: Oh, would you like to read it?

FEDERMAN: Sure. She writes, "Good cooking is a result of a balance struck between frugality and liberality, something I learned in the kitchen of my friend Irving Davis, a bibliophile and classic cook.It is borne out in communities where the supply of food is conditioned by the seasons. Once we lose touch

with the spendthrift aspect of Nature's provisions, epitomized in the raising of a crop, we're in danger of losing touch with life itself. When providence supplies the means, the preparation and sharing of food takes on a sacred aspect. The fact that every crop is of short duration promotes a spirit of making the best of it while it lasts and conserving part of it for future use. It also leads to periods of fasting and periods of feasting, which represent the extremes of the artist situation as well as the Greek Orthodox approach to food and the Catholic insistence on fasting, now abandoned.”

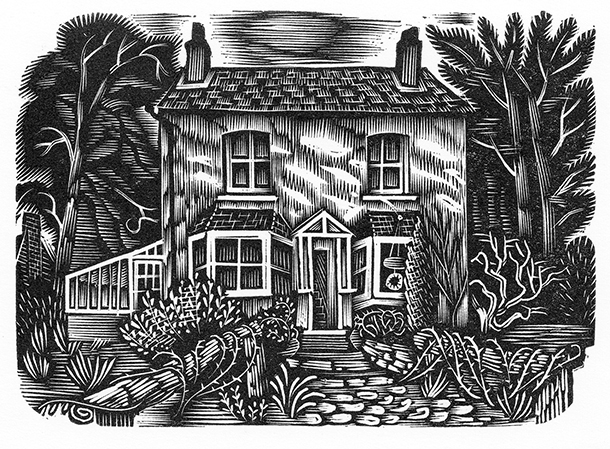

A woodcut by Patience Gray’s friend and colleague David Gentleman depicting the cottage in Rogate where she lived during the second World War. It was here that she sought out foraged foods to supplement meager rations. (Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

PALMER: So, she was obviously way ahead of her time in this focus on seasonality and on eating what was ripe in the garden at that time.

FEDERMAN: She was remarkably ahead of her time, and her book also coincided with a real interest in these ideas. I mean, the Slow Food movement was launched around the time that "Honey for a Weed" was published in 1986, 1987, and I think that Patience captured this ethos of trying to make do with less, to paying attention to what grows in your own environment, and to respecting the soil.

PALMER: So, Adam, tell me a bit about her biography. She was born into an upper middle class family in 1917, but the conventional middle class life never really took with her.

Patience and her daughter Miranda in 1942. (Photo: courtesy of Miranda Armour-Brown)

FEDERMAN: No, and, in fact, that was something that she resisted from a very early age, and traveled quite extensively for a young woman at that time, hitchhiked across Eastern Europe, spent a year in Germany between high school and the London School of Economics where she went in 1935. She was a wonderfully sort of curious person and, I think, sought out these kinds of adventures, and the war I think really was decisive

for her. She was raising two children on her own in a very primitive cottage, and it was here that Patience said she first took an interest in food and cooking. Rationing, you know, impacted everyone in the UK during the war and I think there were certain advantages to living in the countryside. They had access to fresh eggs and certain things that in an urban area you wouldn't have been able to get. However, it was a difficult time, and Patience was essentially alone with her two little children with no electricity, no hot water. You know, water came from a well. They had no car, it was very isolated.

PALMER: But that helped teach her this sort of self-sufficiency that became very fundamental to the way she lived.

FEDERMAN: Yeah, it really was. I mean she continued to live in that way even after the war when she moved back to London. She was living in Hampstead. Patience described it as a kind of village, and it was full of these marvelous people, many of whom were her close friends - architects, designers, intellectuals, writers - and she was right in the middle of that. And I think what's interesting about Patience is that to the extent that people

know her, they know her through her best known book "Honey from a Weed" which describes a very different kind of life, but that period in Hampstead in the 1950s was extremely important to her and to her intellectual awakening. I think it's just an interesting contrast to the life that she would lead after that.

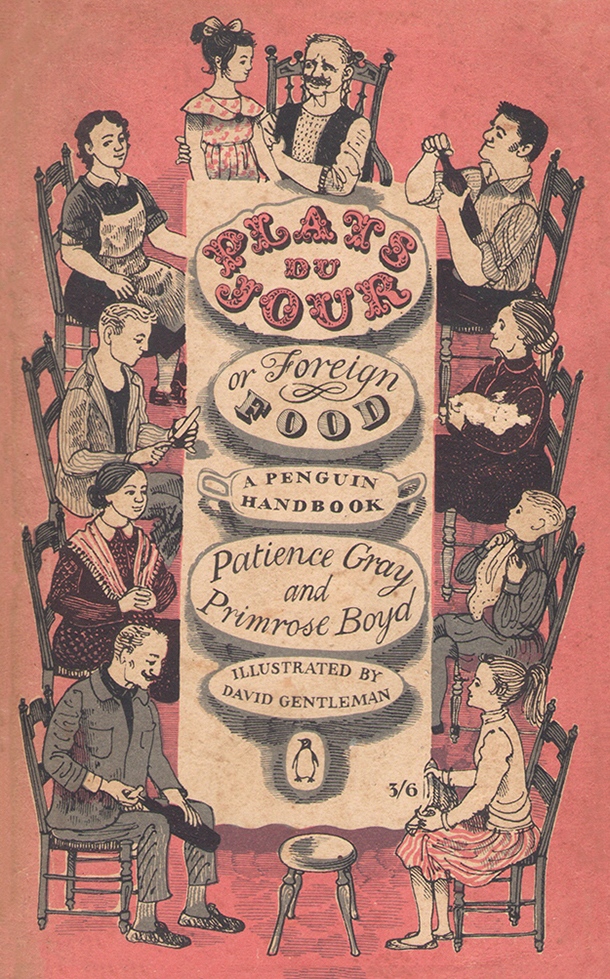

PALMER: Well, it also helped her writing career take off and she published her own foreign food book, "Plats Du Jour" which literally means “Daily Dinners”, and it had recipes for exotic sort of one pot meals such as Boeuf en Daube and risotto and paella aimed at the average British cook, and it was a huge hit.

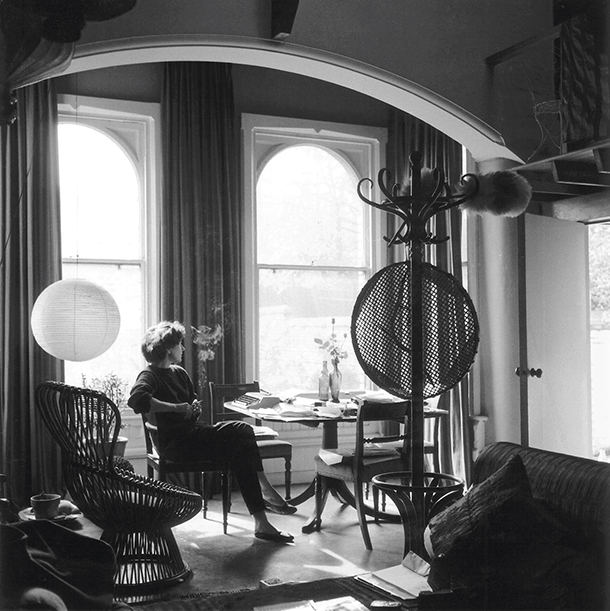

Patience at her desk in the Billiardroom, the room in an old Victorian house she rented in Hampstead after WWII. (Photo: Stefan Buzás / courtesy of Nicolas Gray)

FEDERMAN: It's a remarkable little book, published in 1957. It was really the first mass market paperback of its kind, and the philosophy at the heart of the book really comes from the title, which is this idea of having a single dish and a simple salad and cheese and when possible a bottle of wine to accompany the meal. And the book was very accessible, and it was written by Patience at a time when she didn't consider herself an expert on food, and the idea was to open up the post-war palate.

PALMER: Around this time she meets the sculptor Norman Mommens who becomes her lover and her partner for the rest of her life. Tell me about Norman and his influence on her.

FEDERMAN: Another wonderful figure in this book who really deserves his own biography, a Belgian sculptor, had moved to England in the early 1950s. He and Patience had this really beautiful relationship, and a love affair that lasted, of course, for the rest of their lives, and together they set out on their Mediterranean odyssey in 1962 when they first left England for Carrara.

PALMER: So, what were they searching for when they headed off to the Mediterranean?

FEDERMAN: I'm not so sure they knew exactly what they were searching for. It took them many years to find a place to live and work that sort of met their needs. You know, ultimately, I think they were looking for a life that allowed them the kind of creative expression and freedom that they were both seeking, and you know, Norman, of course, was a sculptor and he needed to work in stone, usually marble. So, they went to places where there was stone. Carrara, the great marble quarries were Michelangelo took some of his stone, the Greek island of Naxos where they lived from 1963 to 1964 before returning to Carrara, where they lived from 1965 to 1970 which is when they ultimately moved to the very southern tip of the heel of Italy and settled for, you know, the next 35 years.

The front cover of Plats du Jour, which Patience co-authored with Primrose Boyd. David Gentleman illustrated the work, which became a cookbook classic. (Photo: courtesy of Penguin Books)

PALMER: Now, their travels to places like Catalonia and Carrara and Naxos crystalized for Patience this kind of thinking about food, particularly the idea of eating wild foraged foods, basically weeds. And it was a remarkable immersion in a kind of disappearing peasant world. Tell me about that.

FEDERMAN: Yeah, it really was. It was an immersion and an engagement with the way of life that Patience in "Honey from a Weed" says was fast disappearing, and she was introduced to the edible plants of each region by the women and children who gathered them. You know, on Naxos, she talks about daily foraging for weeds and bringing them to the village tap where the women and children would tell her what they called them and

how they used them, and I think she does a remarkable job of illuminating that way of life.

PALMER: And that was basically the life that she and Norman embraced when they found their home in Puglia at the very bottom tip of Italy's boot, and, I mean, it sounds awfully glamorous, but it was not at all glamorous, it was a really hard life.

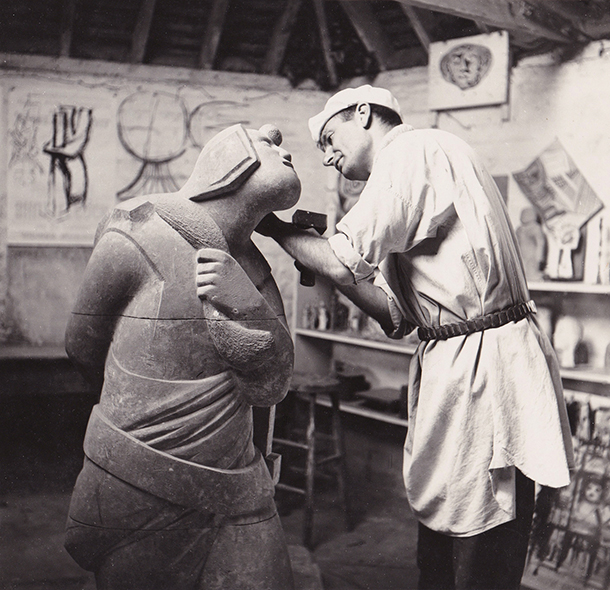

In 1958, Patience met Norman Mommens, the sculptor who would become her partner for the rest of her life. Here, Norman carves Goliath for Leonard Woolf, 1957. (Photo: courtesy of Nicolas Gray)

FEDERMAN: That's right, yeah, and you know I try to dispel in the book the notion that they lived a glamorous quote unquote "simple life" because when it comes down to it there's really nothing very simple about the so-called “simple life,” and they had to work extremely hard, and when they moved to Puglia, the house Spigolizzi, the old stone farmhouse that they moved into was you know, in somewhat dire straits and it took them many many months to make it habitable.

PALMER: Well, yeah, it didn't have running wate. It didn't have heat. It was Spartan, to say the least.

FEDERMAN: Indeed. Up until the time that they moved into it had been used as a makeshift hut for shepherds roaming the hillside. And it's also worth pointing out that the countryside at that time in the early 1970s had been largely abandoned. The Italians themselves were no longer living in the countryside, they’d moved to the villages and towns. So, for Patience and Norman to take up that kind of lifestyle was unconventional to say the least. However, they very much kept up on what was happening in the world. They read the papers, and Norman in particular was deeply concerned about genetically modified food, the impact of nuclear power, and in fact, "Honey from a Weed" -- Patience was finishing up the final edits when the Chernobyl nuclear disaster happened, and she mentions in a letter to her publisher,Alan Davidson, “You know, doesn't all of this seem kind of incidental when we're dealing with these kinds of calamities?”

Norman at the foot of a quarry in Carrara. (Photo: courtesy of Nicolas Gray)

PALMER: There's a passage in your book that kind of describes her attitude to this. It's on page 245. Could you read that?

FEDERMAN: Yes. “If Patience had acquired most of her knowledge of edible wild plants from peasant women, she was well aware that most of her readers would have to rely on books and field guides, a quote unquote "slower and more uncertain method", as she put it. She pointed to Roger Phillips "Wild Food" published in 1983 by way of drawing attention to the risks associated with gathering edible plants in the face of widespread pesticide use and the fallout from industrial pollution. It was a question that she and Alan” -- That’s Alan Davidson, her publisher, -- “had discussed early on. They differed to some extent on whether a cook book was an appropriate venue to raise such concerns. In a letter to Alan after reading Mediterranean Seafood,”- That was one of Alan's books, -- “Patience noted that he had relegated the subject of pollution to a tiny footnote on

scorpion fish and that he had not really addressed the ways in which fish, especially bottom feeders, absorb dangerous toxins. “Can you really say, ‘How fortunate are the English in the wide variety of fish’, Patience wrote, ‘without mentioning the effect of Windscale-Sellafield?’ That was a nuclear power plant that caught fire in 1957, “the impact of this plant on those in the Irish Sea.”

PALMER: So, in the end, how influential do you think Patience was in her vision, in her, in her ideas?

FEDERMAN: That's the hardest question to answer. I mean, I think on the one hand you might say not very influential given that she's not that well known, but on the other, there are a number of food writers, many of them still around today, you know, from Ed Behr and Corby Kummer to John Thorne and Alice Waters, chefs like April Bloomfield and in the UK, Jacob Kenedy and others who were deeply moved by "Honey from a Weed". I would ask these chefs and critics, “What kind of an influence did Patience have on you?” and they would invariably come back and say, “Well, it wasn't really influence. It was something deeper. It was a kind of

spiritual experience.”

PALMER: Yes, and it's not a conventional cookbook as you say. It's a part memoir, part manifesto, full of very simple sort of, like, dishes. I mean, you describe one, and it's just basically bread, olive oil, and a smashed tomato.

Norman and Patience at Spigolizzi in 1971. (Photo: Francesco Radino)

FEDERMAN: Yes, and there's a variation on that dish, I think, throughout the Mediterranean, and it's so wonderfully simple and so delicious, and the very funny thing about that very simple dish, however, is that Patience and Alan had a real disagreement on, on sort of how it was to be prepared because Patience who had eaten this dish in Catalonia many many times had encountered it by smashing the tomatoes and oil on both sides of the bread, and Alan thought this was impossible that the tomatoes would fall off the underside of the bread. So, you know, just to give a sense of how detail oriented he was, and scrupulous, he really forced Patience to consider that dish and how it was constructed.

PALMER: And it is one of the most delicious dishes in the world, a really ripe tomato, a good piece of bread and some good olive oil and a little salt maybe.

FEDERMAN: And that was probably part of Alan's problem, that he was trying it with hard winter tomatoes in London, and it never worked.

Patience being interviewed by the BBC’s Derek Cooper in July 1988. (Photo: courtesy of Nicolas Gray)

PALMER: [LAUGHS] Never! Now, out of all the recipes in the book, in "Honey from the Weed", do you have a favorite yourself?

FEDERMAN: Well, one of the confessions I have to make is that although I've been researching her life for 10 years, I've done very little cooking from "Honey from the Weed". I think it tends to be the kind of book that people read more than they actually use; however, it's an excellent cookbook and I have cooked a handful of recipes from it. One of my favorites actually is just a very simple pasta dish with fresh ricotta cheese, and you reserve some of the water that you boil the noodles in and mix it together with the fresh ricotta and then toss your noodles together with the cheese and the sort of starchy water, and it comes together in this just perfect sauce. A little bit of freshly grated black pepper and parmesan and you have a wonderful dish.

PALMER: Sounds delicious. [LAUGHS]

Adam Federman is a reporting fellow with the Investigative Fund of the Nation Institute, covering energy and the environment, and has written for many publications including The Nation, the Guardian, Gastronomica, and Earth Island Journal. (Photo: Adam Federman)

CURWOOD: Adam Federman’s book is called, Fasting and Feasting, the Life of Visionary Food Writer Patience Gray. He spoke with Living on Earth’s resident Briton, Helen Palmer.

Links

Honey From a Weed by Patience Gray

The Guardian: “Patience Gray’s Honey From a Weed”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth