September 15, 2017

Air Date: September 15, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Caribbean Islands Face Warmer, Stormier Seas

View the page for this story

Smashed and battered by the record-breaking Hurricane Irma, many small Caribbean island nations and territories now face the monumental task of rebuilding much of their infrastructure. For insight on how islands can rebuild, and how every nation can embrace mitigation measures that reduce the threats of extreme weather, Host Steve Curwood spoke with former Grenada UN Ambassador and former Special Advisor for the UN Sustainable Development Goals, Dessima Williams. She says the Caribbean people remain resilient and self-reliant, but global action on climate change is more urgent than ever. (10:15)

The Everglades After Irma

View the page for this story

As well as devastating Florida communities, Hurricane Irma blasted an estimated three to ten feet of storm surge into the Everglades. This “River of Grass” extends from Lake Okeechobee in central Florida down to its southern tip at the Gulf of Mexico, and much of it is a National Park. Host Steve Curwood asked University of Maryland hydrologist Fernando Miralles-Wilhelm how the hurricane’s storm surge and severe downpours, added to the steady rising of the seas, could affect this threatened ecosystem. Professor Miralles-Wilhelm says draining and channelizing the wetlands through decades of development weakened the Everglades’ resilience and ability to buffer storms. (09:01)

Worrisome Right Whale Deaths

View the page for this story

Northern Right whales are endangered, with only about 500 left, so scientists became alarmed this year when 13 carcasses were spotted. Most deaths were in Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence, an area far north of the whale’s usual summer range in the Gulf of Maine. Erin Meyer-Gutbod, a postdoctoral scholar at UC Santa Barbara, tells host Steve Curwood that warmer waters may be driving the favorite food of these whales further north, where the lack of regulation puts the cetaceans at risk of ship strikes and entanglement in fishing gear. (08:41)

The Place Where You Live: Gold Beach, Oregon

/ Andrea LynnView the page for this story

Living on Earth gives voice to Orion magazine’s longtime feature where readers celebrate their favorite places. In this week’s edition, writer Andrea Lynn paints a lyrical image of Gold Beach, Oregon, once a destination for prospectors, and now for tourists and fishermen. (04:41)

Fasting and Feasting: The Life of Visionary Food Writer Patience Gray

View the page for this story

Patience Gray’s pioneering European cookbook brought foreign tastes to the British home cook and her remarkable Honey From a Weed is still a key source of inspiration for popular food writers, yet she’s largely unknown today. A new biography, Fasting and Feasting, introduces her iconoclastic and meandering life, with artists, architects, and radicals in postwar London, and finally to the simplicity of living and cooking off the land at the remote heel of Italy’s boot. In conversation with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer, author Adam Federman shares Patience Gray’s story of lifelong artistic and culinary searching – and whets the appetite too. (14:11)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Dessima Williams, Fernando Miralles-Wilhelm, Erin Meyer-Gutbrod, Adam Federman, Andrea Lynn

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

The southern US will need billions to rebuild and recover, and hurricanes hit some Caribbean islands much harder. They’re not rich, but they have resources beyond money.

WILLIAMS: Well look -- the best protection is people's intelligence and their resilience. And when a disaster hits they have to behave in ways where they can rebound and you see that.

CURWOOD: Also, counting the cost and damage of the massive ocean surge into the Everglades.

MIRALLES-WILHELM: So what these storm surges are doing is that they're sort of bringing all of a sudden large amounts of salt water back. It's almost like nature trying to restore, in a very accelerated way, the natural processes in the Everglades.

CURWOOD: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Caribbean Islands Face Warmer, Stormier Seas

The devastation of the island of Jost Van Dyke – part of the British Virgin Islands – after Hurricane Irma. (Photo: DFID, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Hurricane Irma was most deadly during its Category Five rampage through the Caribbean, smashing the Leeward Islands from Barbuda to Antigua to St. Thomas before scalping the north coast of Cuba. That meteorological monster set records for size, strength, and endurance, records that experts predict will be broken sooner rather than later as global warming continues to heat the oceans and intensify precipitation cycles. And while Florida and the Southeastern US also suffered, these Small Island States - SIDS as they are called in UN climate negotiations - also have the smallest financial capacity to recover and rebuild.

Dessima Williams served as Ambassador for Grenada and as a special advisor for Sustainable Development at the UN, and she joins us now. Ambassador Williams, Welcome to Living on Earth.

WILLIAMS: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: You're from Grenada, Dessima. What's it like to live in a place where, increasingly now, one can expect these just horrific storms?

A cathedral in St. Georges, Grenada that was wrecked by Hurricane Ivan in 2004. (Photo: Ian Mackenzie, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

WILLIAMS: [LAUGHS] I suppose it's like living in New York City where one can expect, you know, gunshots anytime, anywhere. You don't dwell on that. Fortunately, for us, we have many alerts. We've got good systems in place, but you have to change your thinking and change your lifestyle. So, as I said, the way we construct our homes, you know, the way we understand the land. And we see the changes right before our very eyes, but it's a healthy and beautiful and embracing environment and people live more with the positive than with the fear.

CURWOOD: So, Dessima, in what ways is the Caribbean particularly vulnerable to big storms, and what protections and safeguards do some of these islands have that might surprise people?

WILLIAMS: The best protection is people's intelligence and their resilience, and when a disaster hits they have to behave in ways that they can rebound, and you see that. I want to go back to 2004 when, I think, we began this series of intense categories - three, four and five - hurricanes. If you recall how Hurricane Ivan devastated the region, particularly my own country Grenada. 89 percent of all physical structures were either destroyed or damaged, 89 percent, 204 percent was the worth of the GDP loss. That is, everything we owned we lost it twice times over. Now, we've come out of it, and, I think, as intense and destructive as we have seen Hurricane Irma, we will come out of it. But, the question is, did we have to go through that, and at what price will we rebuild?

CURWOOD: So, how do we rebuild after the storm?

WILLIAMS: So, the Caribbean has been responding in a more intelligent way. How we build? We build back better after the storms. We are doing, for example, in agriculture, we are doing climate smart agriculture. That is, planting crops like cassava that endure droughts and floods and are there for food, as opposed to just planting tree crops and, with the first hurricane, it's all gone. So, it's a mix.

On our part, we have to do things better, but I tell you the biggest help is for us to change our lifestyles in the industrial and developed countries where the emissions of carbon really damage the seas and the environment and create this havoc.

CURWOOD: Talk to me a bit about the governance in the Caribbean, in responding to these devastating storms. I mean, we have colonies. Some would say that Puerto Rico is an American colony, the U.S. Virgin Islands an American colony. The French have Saint Martin, and then, of course, there are the independent autonomous countries that have been hard hit. I'm thinking of Cuba. I'm thinking of Antigua. How has the response to the hurricanes been different in those countries both internally and the response from the, the world outside?

Members of the Puerto Rico National Guard clear roadways of fallen trees in the wake of Hurricane Irma. (Photo: courtesy of Puerto Rico National Guard)

WILLIAMS: For those that are still colonies, Saint Martin, Saint Barts, and British Virgin Islands, the metropolitan governments are probably more capable of responding because their resources are massive and they can persuade, maybe, their parliaments to do reconstruction in a manner that suits the colonies. In the case of the independent countries, it's much harder because many of these countries are already highly indebted, in large measure because of the cost of rebuilding from hurricanes.

In the international community, there are agreements that envision that and call for international support and cooperation. The Addis Ababa Action Agenda, the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, the Sustainable Development Agenda 2030. All make provisions for financial support. So, I think that the conversation now has to get started. In the case of the Caribbean it's very difficult because you're looking at countries that have not fully recovered from the economic crisis of 2008, and from the repeated battering from hurricanes. So, I would not be surprised if special measures have to be put in place about the existing debts and the reconstructing.

CURWOOD: How do you expect these big storms will impact the tone or direction of future climate negotiations? I'm thinking there's a big meeting coming up in Bonn in November.

WILLIAMS: Well, this big meeting in Bonn in November, in fact, is chaired by president from a small island state. It is being chaired by Fiji, and the presidency has insisted that the issue of SIDS, small island developing states, will be featured across his one year presidency of the COP. So, I can assure you that there will be much attention to the small island states, not just that they are vulnerable, which they are, but that they are leading their own development with resilience.

There is the green economy, which is agriculture in a particular way, energy in a healthy way and so on, but there is also the blue economy, which is the use of the ocean resources by the ocean countries which by and large many SIDS. So, I think you will see in the negotiations on the one hand call for adaptation support, but on the other hand the countries are mitigating to the extent that we need to because we are not the big violators in the carbon emissions here, but we are transitioning our economies, both in terms of not depleting our resources, using renewable energy. So, those opportunities that SIDS are taking themselves will be put on the table for consideration for the next year of the climate leadership.

Ambassador Dessima Williams just completed her term as Special Adviser for Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals. (Photo: Courtesy of the United Nations)

CURWOOD: What effect do all these storms and flooding have on political stability?

WILLIAMS: Well, it doesn't make it easier for governance because, you know, there's a lot of distraction instead of, you know, worrying about building schools and, you know getting new innovative methods in health care and so on. We're back to basics, and I think it can, in fact, open up new conflicts or old ones.

What we have seen, however, in the Caribbean region is a great coming together across political lines in the immediate aftermath. Not all storms lead to conflict. People have, yes, questioned if their governments have done all they could for preparedness or response or reconstruction, but it hasn't led to the unraveling of the political system or the social cohesion, both of which we need for good reconstruction.

CURWOOD: So, Dessima Williams, you’ve been involved with the climate negotiations for a couple of decades now. What you're seeing right now in these storms, your home territory, the Caribbean, how surprised are you to actually see these massive storms start to move through?

WILLIAMS: Well, I recall years ago when my country Grenada was leading the small island states, and we were arguing that what we will see in climate change, if we don't act in a decisive and urgent manner, is a level of unpredictability and randomness that we could not necessarily control. We've included in the Paris agreement to strengthen global temperature rise, to keep it well below two degrees. We, in the islands, we've argued for well below 1.5, and I think, I'm sorry to say that, but, we are proving that our arguments or our clarion calls were correct, that in fact, we must act urgently because the impacts are going to be first on us, hardest on us as small island states, but it is going to be widespread, and I think the floods from Houston to hurricanes in Florida also suggest that it's not just the islands that will experience this level of climatical chaos, that it is spreading.

CURWOOD: Dessima Williams is an ambassador from Grenada and stepped down recently a special advisor for sustainable development goals at the United Nations. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

WILLIAMS: Thank you. Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Dessima Williams, former Ambassador of Grenada to the United Nations

- The UN Sustainable Development Goals

[MUSIC: Eddie Bullen, “Caribbean Nights” on Desert Rain, CD Baby Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up –Too much water—salt and fresh—for America’s special river of grass. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eddie Bullen, “Told You So” on Desert Rain, CD Baby Records]

The Everglades After Irma

In some parts of the Everglades, “tree islands” arise in the wetland grass landscape. (Photo: vladeb, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Hurricane Irma left a huge human and built environment toll in its devastating wake, and it also roared through the fragile Everglades, the vast subtropical wetland known as the “River of Grass” that covers the southern 20 percent of Florida. It’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and part of it is a National Park, but the Everglades ecosystem is now about half of its original area since people started draining it for development and agriculture in the 1800s. And intense hurricanes have also had an impact.

We turn now to Fernando Miralles-Wilhelm, a hydrologist at the University of Maryland. Professor, welcome to Living on Earth.

MIRALLES-WILHELM: Thank you, thanks for the invitation.

CURWOOD: First, just briefly describe what kind of ecosystem the Everglades is and some of the species that thrive there.

MIRALLES-WILHELM: Right. So, the Everglades is a wetland. It's essentially a land that naturally wants to be wet. It’s a very rich ecosystem with anything that goes from the Florida panther all the way down to snail kites and small fish and the Seaside Stable sparrow, so it's a very rich ecosystem both from the fauna and the flora point of view.

The Everglades is known as the “River of Grass” (Photo: Rick Schwartz, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, people like to call the Everglades the River of Grass. Why is it a river of grass?

MIRALLES-WILHELM: It's a river of grass because, in its natural state, water flows as a very shallow sheet, very slow moving, through the vegetation which naturally was primarily grass until you reach the coastal areas, and the vegetation there starts to change. So, if you actually look at the Everglades from above, from an airplane or from further out, what you see is a very expanse matrix of grass, you know, with some little bits of trees here and there, and these are the natural parts of the Everglades that still exist. If you look at the history of the Everglades, in particularly how it relates to development in south Florida, the Everglades were drained systematically in order to develop the land, places like Miami and inland and south of Miami and also north of Miami, so Fort Lauderdale, West Palm Beach. These were areas that actually were developed through draining the Everglades.

CURWOOD: So, given that the Everglades goes between fresh and salt water at that threshold, what kind of impact could that storm surge that was brought by Hurricane Irma had on the Everglades?

MIRALLES-WILHELM: If you think about the storm surge, it's almost like nature trying to restore, in a very accelerated way, the natural processes in the Everglades. Fresh water flows from Lake Okeechobee south and gets discharged as a very slow moving sheet to the coast. That was balanced by the coastal environment, which is the boundary with the sea, sort of created this interface between fresh water and salt water. What has happened is that with all this development is we have created a number of pulses, much larger than natural, of fresh water into the coast and this has affected the marine ecosystem. So, what these storm surges are doing is that they're sort of bringing all of a sudden large amounts of salt water back, and sort of trying to recreate that interface that we have lost. Now, doing it in such a sudden way, through one of these extreme storms, Irma and others that have happened in the past, it's of course not the ideal way to restore a natural ecosystem. But that is nature sort of coming back at you in a way.

CURWOOD: What do we know at this point about approximately how much storm surge in the Everglades was experienced as Hurricane Irma passed through?

MIRALLES-WILHELM: We're seeing numbers from as low as three feet and as high as more than 10 in different places. It's not trivial at all.

Mangroves in Everglades National Park. (Photo: Vincent Lammin, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Fernando, Irma also brought a lot of rain. To what extent do downpours affect that fresh-to-salt water balance in the Everglades, and how much could the wetlands actually benefit from all that rain as well as the storm surge?

MIRALLES-WILHELM: So, the other part of storms like Irma is, of course, is the fresh water that's poured on top of the wetlands. So, imagine what's happening at the same time. You have lots of fresh water falling on the wetlands and trying to get out to the coast because of the topography and because of these channels are there, and then the storm water surge bringing in seawater in. And so, you have these two, sort of like a collision of waters. You have fresh water trying to get out, salt water in. The dynamics of that interface and where it is, between the fresh water and salt water, has likely changed, pre- and post-Irma.

For places that gain fresh water, you know, the fresh water species will tend to thrive. And, you know, there are a few species like that, vegetation-wise that thrive, and the grasses are one example. So, grasses like to be inundated. Trees, on the other hand, don't like to be flooded. Then, on the other hand if you look at the salt water piece, species that like salt water like mangroves, like some species of fish, will thrive. So, you could see, and we've seen this before, sort of a redistribution of vegetation across the Everglades.

CURWOOD: Of course, if Florida is known for its alligators and, at the very southern edge of the Everglades where it starts to get pretty salty, there are crocodiles. With the increased salinity how much more risk is there from crocodiles moving upstream as it were?

An alligator in the Everglades. Increasing salinity could attract crocodiles, which live in brackish environments, into freshwater alligator territory. (Photo: Sheila Sund, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

MIRALLES-WILHELM: I mean the risk is there. We haven't done that analysis yet. We haven't started collecting data yet. We'll know a lot more over the next few weeks to months.

CURWOOD: And I ask about crocodiles because, as you know alligators are, well, they're relatively laid back in comparison to even the American crocodile which, you know, seems to start its day thinking, “I need to get a meal or several before it's over.”

MIRALLES-WILHELM: [LAUGHS] Yes.

CURWOOD: Fernando, how have human activities that disrupt the natural hydrologic cycle in the Everglades weakened the Everglades resilience in the face of a changing climate?

MIRALLES-WILHELM: Right, so this story is fairly straightforward. If you look at a map of south Florida or even if you actually look at it from an airplane when you fly into Miami or Fort Lauderdale, what you see is these canals that run from the urban locations to the coast, and what we actually have built is a very sophisticated network of canals that was designed to get water out of the system as quickly as we needed to, in order to not flood, in order to be able to build, make land available for development, etc. When we built those canals, we're essentially short circuiting the slow-moving, natural flow of water that occurred before. We have accelerated the drainage, and we have reduced the ability of the system to hold the water and to be that buffer.

And I think the new vision and the vision that we have missed in all these decades is that the Everglades could have been used to co-exist with the urban development that took place. I think we decided collectively not to live with the water. We decided we wanted the water out, and what that has created is that now we are trying to say, well, “How can we start living with the water?”

CURWOOD: Now, Professor, I understand that you lived in and taught in Miami for a decade, and you recently were one of the authors of a scientific review of the progress that's been made in restoring the Everglades. Please, just take a moment to give us a brief overview of why the Everglades is already undergoing a decades-long restoration.

Professor Fernando Miralles-Wilhelm teaches hydrology at the University of Maryland and formerly taught at Florida International University. (Photo: University of Maryland)

MIRALLES-WILHELM: So, you have this balance that we've broken, that we’ve made fragile. So, the overall Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan, or CERP, as it's called, was authorized by Congress back in 2000, and it's been ongoing ever since. The project is really more like a program because it's got over 60 large scale projects. So, the purpose of the CERP is to try to restore some capability of the system to sort of hold water in a way that you could protect the south Florida region both from floods and droughts and provide that buffer, which is just what the wetlands, the natural wetlands, used to do. A hurricane is not always going to be like Irma. Irma is just the one that's fresh in our minds because it just happened. Every storm has a distinct set of characteristics, and we need to be prepared to deal with this range of variability and the Everglades, the wetland, is our best bet to be able to deal with this variability, so we have to see the Everglades as our best friend.

CURWOOD: Professor Fernando Miralles-Wilhelm is a hydrologist at the University of Maryland. Thank you so much, Professor, for taking the time today.

MIRALLES-WILHELM: Thanks very much.

Related links:

- National Wildlife Federation: About Hurricanes and Wetlands

- Gizmodo: “Why the Everglades Might Never Look the Same After Hurricane Irma”

- The 2016 National Academies report Miralles-Wilhelm coauthored: “Progress Toward Restoring the Everglades”

- About Univ. of Maryland Professor Fernando Miralles-Wilhelm

[MUSIC: Mark O’Connor and the Metamorphosen Chamber Orchestra/Scott Yoo, “Strings and Threads Suite, 01, Fair Dance Reel,” on The American Seasons, Sony Classical]

Worrisome Right Whale Deaths

North Atlantic right whales, an endangered species, usually spend their summers in and around the Gulf of Maine to feed on copepods. (Photo: Moira Brown / the New England Aquarium, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: They called them “right whales” because they were the “right” whales to hunt, rich in blubber and baleen, slow-moving, and likely to float, not sink, when harpooned. These qualities spelled the near extinction of the mighty right whale, but thanks to the discovery of oil, laws to protect them from hunting and time, numbers have rebounded and now some 10,000 of them swim in the southern ocean. But in the north Atlantic, there are less than 500 Northern right whales, and, when 13 of them were found dead this summer, NOAA declared an “Unusual Mortality Event.”

10 of those dead whales were in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and researchers at Cornell suspect fast warming ocean waters may be a reason why. Erin Meyer-Gutbrod, a post-doctoral scholar at UC Santa Barbara is part of that team. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MEYER-GUTBROD: Thanks for having me on your show.

CURWOOD: So, how unusual is it to find right whales as far north as the Gulf of St. Lawrence?

MEYER-GUTBROD: So, that's a pretty tricky question because there hasn't been a lot of survey effort up there. The right whales traditionally start off in the spring off of Cape Cod Bay, and then they spend their summer in the Gulf of Maine and Bay of Fundy and off the Scotian shelf. And, while they're seen occasionally farther north than that, it's never been considered a traditional part of their feeding grounds. But what's happened in the past few years is the intensive survey effort counting right whales in the Gulf of Maine and Bay of Fundy area has seen much fewer right whales than they're used to seeing over the summer.

And so this caused sort of a brief crisis where the scientists were wondering, “Where have all the whales gone? Is it possible that there's been a mass mortality event?” And it actually caused scientists to start looking farther afield to see where these whales are spending their time in the summer. So, they've just started a more intensive survey effort up in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and so we're thinking that the right whales are beginning to occupy as of the past several years the Gulf of St. Lawrence in much higher numbers than has been seen in the past.

CURWOOD: So, let me ask you this. You talk about 13 deaths. Where did you find those whale carcasses?

MEYER-GUTBROD: Well, that's part of why this story is so unusual. First of all, the number 13 is higher than any previous year in terms of carcasses found, and, with a population that only has about 500 hundred, 13 is more than two percent. So, this year seeing 13, and then 10 of them are up in the Gulf of St Lawrence, this is completely unprecedented.

CURWOOD: So, of the 13 Northern right whale carcasses that were observed, what do you think killed them? What did the necropsy show?

MEYER-GUTBROD: Results from the necropsies aren't available yet, they take a couple of months. So, there is some preliminary evidence of both vessel strikes and entanglement, but we're all waiting with bated breath to hear the results of these necropsies.

CURWOOD: So, the obvious question is then, what do you suspect is causing so many deaths among the Northern right whales, and for you to find these carcasses, so many in the Gulf of St Lawrence and Canada?

Warming waters in the Gulf of Maine may be affecting prey availability for North Atlantic right whales and lowering their birth rates. (Photo: NOAA, Wikimedia commons public domain)

MEYER-GUTBROD: Well, the right whales are traditionally occupying the Gulf of Maine, and as a result the US has put in many protections for this species so that they won't be as vulnerable to fishing gear entanglement and ship strikes, and the US has implemented regulations including mandatory vessel speed reductions. Scientists have put a series of hydrophones in the water. Hydrophones are underwater listening devices. When they hear a right whale, they can then send out a message to all of the boats that are in the area saying, “Hey, there's a right whale nearby. Please slow down”. And then the fishing industry has also made a lot of changes. A lot of the fishing lines now run along the sea floor instead of in the middle of the water, which makes it a lot harder for a whale to get tangled up in them. So, these are expensive fishing gear implementations that have actually made a big difference in the rates of anthropogenic mortalities in the Gulf of Maine. Now, all of a sudden the whales are heading up farther north where these protections haven't been implemented because the whales aren't traditionally there, so why should Canada put in the resources to make these expensive changes? But now that we've seen them up there everybody is scrambling to figure out why and to figure out how we can put the same protections in place in the Gulf of St. Lawrence that are already in place in the Gulf of Maine.

CURWOOD: So, how is this related, do you think, to climate change?

MEYER-GUTBROD: Well, that's an interesting question and one that we can't fully answer, but I've been looking at changes in right whale demography over a 30 year time series, and I found that the changes in the amount of food that the right Whales eat - Whales eat copepods called Calanus Finmarchicus, and there's high degree of variability each year in the amount of these copepods, and in years when there's not a lot of copepods, the right whales tend to have fewer babies. So, the problem is, the females, it's a very energetically intensive process to be pregnant, to spend a year lactating, and then whether or not a female is able to have another calf quickly depends on how quickly she can replenish the blubber that she lost during her previous pregnancy and lactation. With this rapid warming that's happened in the past few years in the Gulf of Maine, scientists are wondering whether or not the warmth has caused fewer copepods available for the whales to eat. Unfortunately, we've been monitoring copepod abundance for 60 years straight, and due to budget cuts in 2011 we stopped processing these samples. So, we actually don't know whether or not the Gulf of Maine is filled with copepods in these past few years.

CURWOOD: And, for the non-scientists listening to us, just briefly describe copepods.

MEYER-GUTBROD: Copepods, you can think of them sort of as a bug in the sea. The right whales like these copepods because they're really fatty. So, they're rich and calorically intensive, compared to the other zooplankton of similar sizes.

CURWOOD So, I gather you're trying to connect these dots here, that you're suspecting that there is, in fact,

the copepods that right whales like to eat there’s more of that up in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and less of it now in the Gulf of Maine, and they're moving not so much because they're finding the water a little bit warmer, but because their food is.

MEYER-GUTBROD: That's right. That's the theory, and at least the modeling studies that I've done in

the past do not indicate that whales are dying because of lack of food. It's much more likely that

they're just reproducing much slower. The question is more, if they're searching for food, what is that

going to mean in terms of the more common forms of mortality, which are anthropogenic in origin, these

fishing gear entanglements and vessel strikes? So, if the right whales go straight to the same places, we're

able to implement those protections. However, if the prey availability changes, and the distribution of these

copepods change, then these right whales need to spend more time swimming, looking around for those

dense patches that they need to eat, so more time swimming – I mean you do the math -- it just increases the

chance of getting entangled in fishing gear.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Now, Erin, what kind of discussions are going on with the Canadian environmental Authorities to see about making the Gulf of St. Lawrence a safer place for right whales to be?

Erin Meyer-Gutbrod studies right whale demography and looks at how climate mechanisms affect right whale populations. (Photo: courtesy of Erin Meyer-Gutbrod)

MEYER-GUTBROD: Yeah, the DFO in Canada is very concerned with the huge mortality event that’s happened with right whales up in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. So, Fisheries and Oceans Canada has made some moves to implement protection on the fly. At first they instituted some voluntary vessel speed reductions, and then a couple of weeks ago, those have transitioned in to mandatory speed reductions for vessels of a certain size. Canada also closed their snow crab fishery early to try and pull some of the gear out of the water to reduce the chance of entanglement, and I believe there are other fisheries that are being delayed, the crab fisheries, to try and wait until the right whales have left their summer feeding grounds before they put all this gear in the water.

CURWOOD: Erin Meyer-Gutbrod is a post doc at UC Santa Barbara. Thanks for taking

the time with us today.

MEYER-GUTBROD: Thanks for having me on your show.

Related links:

- Cornell University press release: “Right whale deaths may be a casualty of climate crisis”

- The Ellsworth American: “NOAA, Canadian Fisheries pursue cause of right whales deaths”

- Portland Press Herald: “Researchers find summer heat’s lasting longer in the Gulf of Maine”

- Portland Press Herald: “Mayday: Gulf of Maine In Distress”

- Erin Meyer-Gutbrod’s web page

[MUSIC: Paul Winter/Paul Halley, “Lullaby From the Great Mother Whale To the Baby Seal Pups” on Concert For the Earth, Living Music.]

The Place Where You Live: Gold Beach, Oregon

Flecks of gold shine in the sand near Gold Beach (Photo: Andrea Lynn)

CURWOOD: We head to Oregon now for another installment in the occasional Living on Earth/Orion Magazine series “The Place Where You Live.” Orion invites readers to submit essays to the magazine’s website to put places they love on the map, and we give them a voice.

[MUSIC: Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes “Home” from Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes, Rough Trade Records]

CURWOOD: The view of the Pacific coast from a mountaintop inspired today’s essay.

LYNN: Gold Beach is a collision of old and new, of fast-paced tourist community right at the southern coast of Oregon. And the Pacific Coastal Highway runs though the town, so especially in summer it’s extremely busy with a lot of visitors enjoying the rugged, natural surroundings.

[MUSIC: Guitar Dreamers and Acoustic Guitars, “Dirty Paws" on Acoustic Nature Walk, composed by Nanna Bryndís Hilmarsdóttir/ Ragnar Þórhallsson/Of Monsters and Men, CC Entertainment]

Anna Hummingbirds flit between fuchsia flowers. (Photo: Andrea Lynn)

LYNN: I’m Andrea Lynn. This is my essay on Gold Beach, Oregon.

The staccato sounds of rubber bullets ripping the air at the marina below unsettle nature atop the mountain, alive with wind arias through the Douglas-firs, iridescent Anna’s Hummingbirds jetting between the fuchsia flower pendants, chipmunks arguing for control of the deepest red thimbleberries, and the thunder of the Pacific. Scolding sea lion voices rise on summer’s air, annoyed at the tortuous deterrence methods doled out by the

chinook salmon fishermen, afraid their catches will be disrupted, lost back to the mighty Rogue River, or worse, to the shiny mouth of a waiting sea lion.

[SOUNDS OF BIRDS AND SEA LIONS]

LYNN: The fog quilt that settles over the marina and town on late summer days is comfortable to view from the vantage point of the mountain top. The elevation atop, although only 1,600 feet, provides an expansive, sun-soaked escape from the greyness lying beneath the cloud-weave blanket. If stuck beneath the blanket, a friend can be found in the whipping wind that keeps the fog pushed back, if only from the Pacific’s immediate coastline.

The fog rolls in, coming towards Andrea’s greenhouse and garden. (Photo: Andrea Lynn)

Standing in the rich, gold-dusted brown sand, it is enticing to ponder the shapes of Oregon’s coastal rock formations – the sea stacks, arches and tiny islands that make up the Oregon Islands National Wildlife Refuge. Kissing Rock, the nearest formation to Gold Beach’s southern border, is a common location for conversations between strangers, as eyes attempt to bring into focus the lips carved by the rugged waves into the stone, a mouth posed in a kiss upward for the sky.

Back at the top of the mountain the vineyard teaches the critical principle of southern exposure’s sacred value, and the sunflowers indicate direction, floppy-headed compasses following the sun across the 360-degree panoramic view from the forests on the eastern peaks to the western horizon’s blue expanse.

Kissing rock stands tall in the Pacific. (Photo: Andrea Lynn)

The field crickets begin their music almost precisely as the sun vanishes into magenta shadows, and the resident Great Horned Owl is left

to ponder alone, how long ago Gold Beach’s gold washed into the sea.

[CRICKETS BUZZING, OWL HOOTING]

[MUSIC: Guitar Dreamers and Acoustic Guitars, “Dirty Paws” on Acoustic Nature Walk, composed by Of Monsters and Men, CC Entertainment

LYNN: The old timers in Gold Beach will tell you about the gold that is indeed in the sand. And if you do look closely at the sand, especially in the sunshine, you see gold flecks. And the opportunity to gather up such tiny flakes is really cost-prohibitive, but you will often see people panning for gold in the streams

that run into the ocean. So, gold is very much still a part of the heritage that makes Gold Beach what it is.

[MUSIC: Guitar Dreamers and Acoustic Guitars, “Dirty Paws” on Acoustic Nature Walk, composed by Of Monsters and Men, CC Entertanment]

LYNN: It’s almost surreal sitting at the top of the mountain looking down over the Pacific and taking just time to pause and realize, in that place, when you’re there, time does disappear.

The summer sunset from Andrea’s deck. (Photo: Andrea Lynn)

[MUSIC: Guitar Dreamers and Acoustic Guitars, “Dirty Paws” on Acoustic Nature Walk, composed by Of Monsters and Men, CC Entertainment]

CURWOOD: That’s Andrea Lynn and her essay about Gold Beach, Oregon. You can find pictures and details about Orion Magazine and how to submit your essay, if you want to tell us about the place where you live, at our website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- Andrea Lynn’s essay on the Orion website

- Andrea Lynn’s applied journalism website

[MUSIC: Guitar Dreamers and Acoustic Guitars, “Dirty Paws” on Acoustic Nature Walk, composed by Of Monsters and Men, CC Entertainment]

CURWOOD: Coming up, eating like a peasant, the joy of foraging for weeds. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies – combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, “Blu Bop” on Live Art, composed by Bela Fleck/Howard Levy/Victor Wooten/Roy Wooten, Warner Bros]

Fasting and Feasting: The Life of Visionary Food Writer Patience Gray

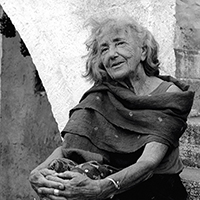

Patience at Spigolizzi in the mid 1990s. (Photo: Doris Schiuma)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. The early 1960s saw a revolution in ideas about food and home cooking. In the US, there was Julia Child, but a decade earlier austerity-weary Britons discovered adventurous, foreign tastes thanks to “A Book of Mediterranean Food” written by Elizabeth David. But she wasn’t the only culinary pioneer in the UK, and a new biography “Fasting and Feasting” introduces another, Patience Gray. She was an iconoclastic artist, writer, traveler and almost incidental cookbook writer, whose “Honey from a Weed” inspired cooks on both sides of the Atlantic. “Fasting and Feasting, the Life of Visionary Food Writer Patience Gray” is written by one-time bread baker and pastry chef Adam Federman, who spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

PALMER: Now, Adam Federman, what drew you to Patience Gray and her unusual but highly influential cookbook "Honey from a Weed"?

Patience and her childhood friend Betty Barnardo traveling in Germany in 1937. (Photo: courtesy of Miranda Armour-Brown)

FEDERMAN: There were many things. I mean, the interesting thing is that I had never heard of Patience until after she died in 2005 when I read an obituary in the Art of Eating food magazine, which described "Honey from a Weed" as one of the best books that will ever be written about food, and that struck me as a bit lofty, but I was, you know, equally intrigued to find out more about the book and the woman who wrote it, and then it turned out that my parents had a copy of "Honey from a Weed" on their bookcase that had been given to them years before, and I had never noticed. And as soon as I opened the book I was really swept away by the prose and the world that Patience described.

PALMER: What was it about the writing that particularly took you?

FEDERMAN: It engages you from the first page, and she has a remarkably vivid way of describing the world that she and her partner Norman lived in. But it was also her approach to food and cooking, and there's a section from the introduction that I think captures that quite well.

PALMER: Oh, would you like to read it?

FEDERMAN: Sure. She writes, "Good cooking is a result of a balance struck between frugality and liberality, something I learned in the kitchen of my friend Irving Davis, a bibliophile and classic cook.It is borne out in communities where the supply of food is conditioned by the seasons. Once we lose touch

with the spendthrift aspect of Nature's provisions, epitomized in the raising of a crop, we're in danger of losing touch with life itself. When providence supplies the means, the preparation and sharing of food takes on a sacred aspect. The fact that every crop is of short duration promotes a spirit of making the best of it while it lasts and conserving part of it for future use. It also leads to periods of fasting and periods of feasting, which represent the extremes of the artist situation as well as the Greek Orthodox approach to food and the Catholic insistence on fasting, now abandoned.”

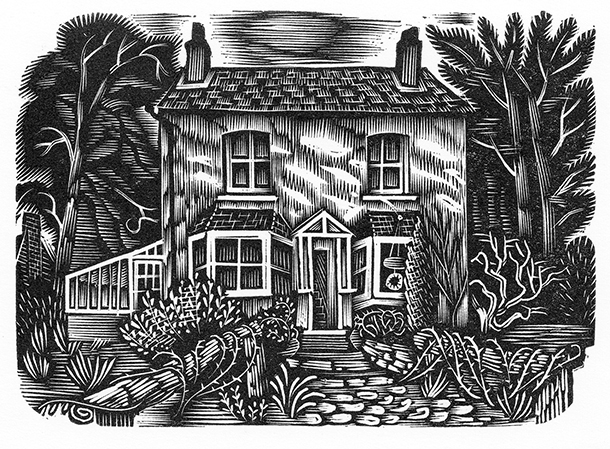

A woodcut by Patience Gray’s friend and colleague David Gentleman depicting the cottage in Rogate where she lived during the second World War. It was here that she sought out foraged foods to supplement meager rations. (Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

PALMER: So, she was obviously way ahead of her time in this focus on seasonality and on eating what was ripe in the garden at that time.

FEDERMAN: She was remarkably ahead of her time, and her book also coincided with a real interest in these ideas. I mean, the Slow Food movement was launched around the time that "Honey for a Weed" was published in 1986, 1987, and I think that Patience captured this ethos of trying to make do with less, to paying attention to what grows in your own environment, and to respecting the soil.

PALMER: So, Adam, tell me a bit about her biography. She was born into an upper middle class family in 1917, but the conventional middle class life never really took with her.

Patience and her daughter Miranda in 1942. (Photo: courtesy of Miranda Armour-Brown)

FEDERMAN: No, and, in fact, that was something that she resisted from a very early age, and traveled quite extensively for a young woman at that time, hitchhiked across Eastern Europe, spent a year in Germany between high school and the London School of Economics where she went in 1935. She was a wonderfully sort of curious person and, I think, sought out these kinds of adventures, and the war I think really was decisive

for her. She was raising two children on her own in a very primitive cottage, and it was here that Patience said she first took an interest in food and cooking. Rationing, you know, impacted everyone in the UK during the war and I think there were certain advantages to living in the countryside. They had access to fresh eggs and certain things that in an urban area you wouldn't have been able to get. However, it was a difficult time, and Patience was essentially alone with her two little children with no electricity, no hot water. You know, water came from a well. They had no car, it was very isolated.

PALMER: But that helped teach her this sort of self-sufficiency that became very fundamental to the way she lived.

FEDERMAN: Yeah, it really was. I mean she continued to live in that way even after the war when she moved back to London. She was living in Hampstead. Patience described it as a kind of village, and it was full of these marvelous people, many of whom were her close friends - architects, designers, intellectuals, writers - and she was right in the middle of that. And I think what's interesting about Patience is that to the extent that people

know her, they know her through her best known book "Honey from a Weed" which describes a very different kind of life, but that period in Hampstead in the 1950s was extremely important to her and to her intellectual awakening. I think it's just an interesting contrast to the life that she would lead after that.

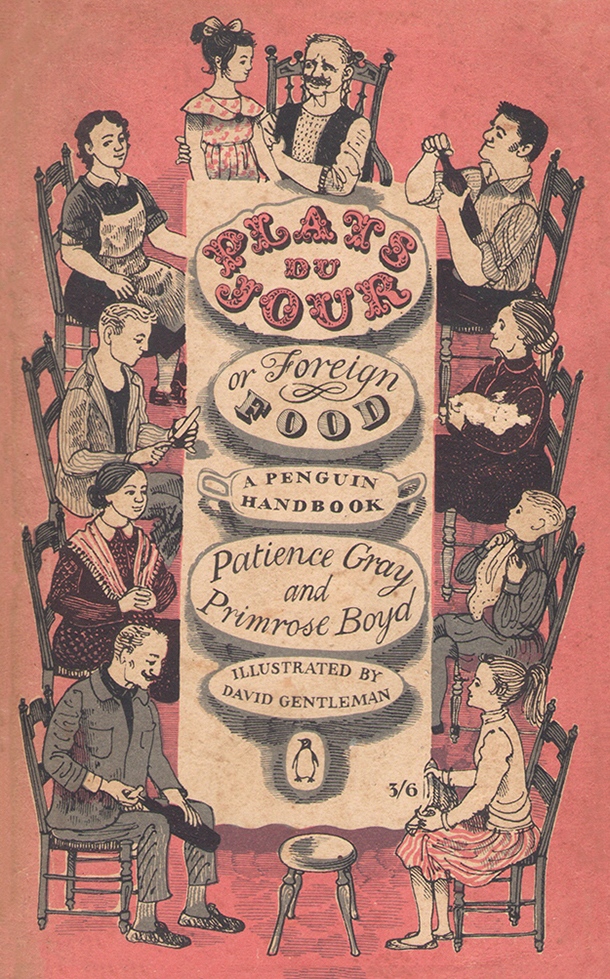

PALMER: Well, it also helped her writing career take off and she published her own foreign food book, "Plats Du Jour" which literally means “Daily Dinners”, and it had recipes for exotic sort of one pot meals such as Boeuf en Daube and risotto and paella aimed at the average British cook, and it was a huge hit.

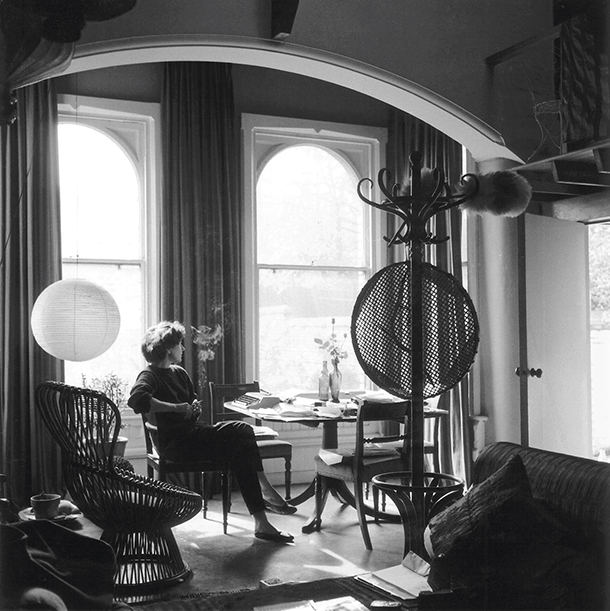

Patience at her desk in the Billiardroom, the room in an old Victorian house she rented in Hampstead after WWII. (Photo: Stefan Buzás / courtesy of Nicolas Gray)

FEDERMAN: It's a remarkable little book, published in 1957. It was really the first mass market paperback of its kind, and the philosophy at the heart of the book really comes from the title, which is this idea of having a single dish and a simple salad and cheese and when possible a bottle of wine to accompany the meal. And the book was very accessible, and it was written by Patience at a time when she didn't consider herself an expert on food, and the idea was to open up the post-war palate.

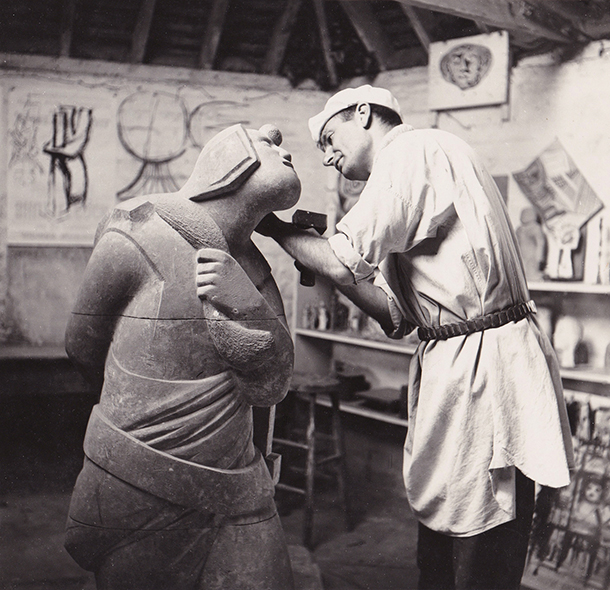

PALMER: Around this time she meets the sculptor Norman Mommens who becomes her lover and her partner for the rest of her life. Tell me about Norman and his influence on her.

FEDERMAN: Another wonderful figure in this book who really deserves his own biography, a Belgian sculptor, had moved to England in the early 1950s. He and Patience had this really beautiful relationship, and a love affair that lasted, of course, for the rest of their lives, and together they set out on their Mediterranean odyssey in 1962 when they first left England for Carrara.

PALMER: So, what were they searching for when they headed off to the Mediterranean?

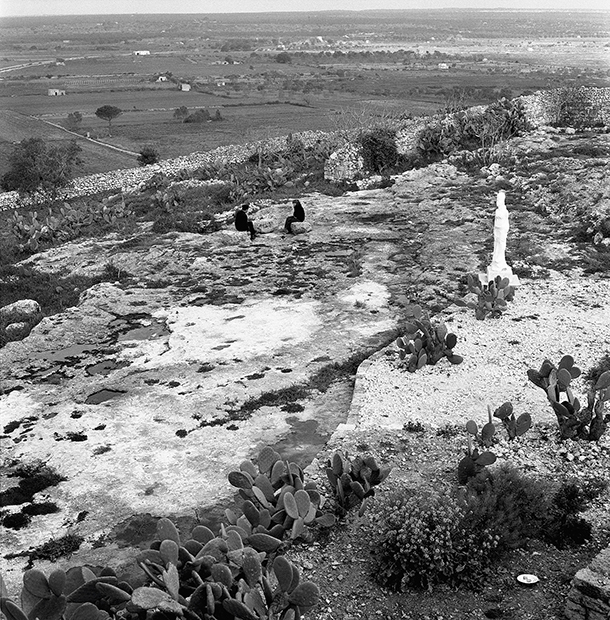

FEDERMAN: I'm not so sure they knew exactly what they were searching for. It took them many years to find a place to live and work that sort of met their needs. You know, ultimately, I think they were looking for a life that allowed them the kind of creative expression and freedom that they were both seeking, and you know, Norman, of course, was a sculptor and he needed to work in stone, usually marble. So, they went to places where there was stone. Carrara, the great marble quarries were Michelangelo took some of his stone, the Greek island of Naxos where they lived from 1963 to 1964 before returning to Carrara, where they lived from 1965 to 1970 which is when they ultimately moved to the very southern tip of the heel of Italy and settled for, you know, the next 35 years.

The front cover of Plats du Jour, which Patience co-authored with Primrose Boyd. David Gentleman illustrated the work, which became a cookbook classic. (Photo: courtesy of Penguin Books)

PALMER: Now, their travels to places like Catalonia and Carrara and Naxos crystalized for Patience this kind of thinking about food, particularly the idea of eating wild foraged foods, basically weeds. And it was a remarkable immersion in a kind of disappearing peasant world. Tell me about that.

FEDERMAN: Yeah, it really was. It was an immersion and an engagement with the way of life that Patience in "Honey from a Weed" says was fast disappearing, and she was introduced to the edible plants of each region by the women and children who gathered them. You know, on Naxos, she talks about daily foraging for weeds and bringing them to the village tap where the women and children would tell her what they called them and

how they used them, and I think she does a remarkable job of illuminating that way of life.

PALMER: And that was basically the life that she and Norman embraced when they found their home in Puglia at the very bottom tip of Italy's boot, and, I mean, it sounds awfully glamorous, but it was not at all glamorous, it was a really hard life.

In 1958, Patience met Norman Mommens, the sculptor who would become her partner for the rest of her life. Here, Norman carves Goliath for Leonard Woolf, 1957. (Photo: courtesy of Nicolas Gray)

FEDERMAN: That's right, yeah, and you know I try to dispel in the book the notion that they lived a glamorous quote unquote "simple life" because when it comes down to it there's really nothing very simple about the so-called “simple life,” and they had to work extremely hard, and when they moved to Puglia, the house Spigolizzi, the old stone farmhouse that they moved into was you know, in somewhat dire straits and it took them many many months to make it habitable.

PALMER: Well, yeah, it didn't have running wate. It didn't have heat. It was Spartan, to say the least.

FEDERMAN: Indeed. Up until the time that they moved into it had been used as a makeshift hut for shepherds roaming the hillside. And it's also worth pointing out that the countryside at that time in the early 1970s had been largely abandoned. The Italians themselves were no longer living in the countryside, they’d moved to the villages and towns. So, for Patience and Norman to take up that kind of lifestyle was unconventional to say the least. However, they very much kept up on what was happening in the world. They read the papers, and Norman in particular was deeply concerned about genetically modified food, the impact of nuclear power, and in fact, "Honey from a Weed" -- Patience was finishing up the final edits when the Chernobyl nuclear disaster happened, and she mentions in a letter to her publisher,Alan Davidson, “You know, doesn't all of this seem kind of incidental when we're dealing with these kinds of calamities?”

Norman at the foot of a quarry in Carrara. (Photo: courtesy of Nicolas Gray)

PALMER: There's a passage in your book that kind of describes her attitude to this. It's on page 245. Could you read that?

FEDERMAN: Yes. “If Patience had acquired most of her knowledge of edible wild plants from peasant women, she was well aware that most of her readers would have to rely on books and field guides, a quote unquote "slower and more uncertain method", as she put it. She pointed to Roger Phillips "Wild Food" published in 1983 by way of drawing attention to the risks associated with gathering edible plants in the face of widespread pesticide use and the fallout from industrial pollution. It was a question that she and Alan” -- That’s Alan Davidson, her publisher, -- “had discussed early on. They differed to some extent on whether a cook book was an appropriate venue to raise such concerns. In a letter to Alan after reading Mediterranean Seafood,”- That was one of Alan's books, -- “Patience noted that he had relegated the subject of pollution to a tiny footnote on

scorpion fish and that he had not really addressed the ways in which fish, especially bottom feeders, absorb dangerous toxins. “Can you really say, ‘How fortunate are the English in the wide variety of fish’, Patience wrote, ‘without mentioning the effect of Windscale-Sellafield?’ That was a nuclear power plant that caught fire in 1957, “the impact of this plant on those in the Irish Sea.”

PALMER: So, in the end, how influential do you think Patience was in her vision, in her, in her ideas?

FEDERMAN: That's the hardest question to answer. I mean, I think on the one hand you might say not very influential given that she's not that well known, but on the other, there are a number of food writers, many of them still around today, you know, from Ed Behr and Corby Kummer to John Thorne and Alice Waters, chefs like April Bloomfield and in the UK, Jacob Kenedy and others who were deeply moved by "Honey from a Weed". I would ask these chefs and critics, “What kind of an influence did Patience have on you?” and they would invariably come back and say, “Well, it wasn't really influence. It was something deeper. It was a kind of

spiritual experience.”

PALMER: Yes, and it's not a conventional cookbook as you say. It's a part memoir, part manifesto, full of very simple sort of, like, dishes. I mean, you describe one, and it's just basically bread, olive oil, and a smashed tomato.

Norman and Patience at Spigolizzi in 1971. (Photo: Francesco Radino)

FEDERMAN: Yes, and there's a variation on that dish, I think, throughout the Mediterranean, and it's so wonderfully simple and so delicious, and the very funny thing about that very simple dish, however, is that Patience and Alan had a real disagreement on, on sort of how it was to be prepared because Patience who had eaten this dish in Catalonia many many times had encountered it by smashing the tomatoes and oil on both sides of the bread, and Alan thought this was impossible that the tomatoes would fall off the underside of the bread. So, you know, just to give a sense of how detail oriented he was, and scrupulous, he really forced Patience to consider that dish and how it was constructed.

PALMER: And it is one of the most delicious dishes in the world, a really ripe tomato, a good piece of bread and some good olive oil and a little salt maybe.

FEDERMAN: And that was probably part of Alan's problem, that he was trying it with hard winter tomatoes in London, and it never worked.

Patience being interviewed by the BBC’s Derek Cooper in July 1988. (Photo: courtesy of Nicolas Gray)

PALMER: [LAUGHS] Never! Now, out of all the recipes in the book, in "Honey from the Weed", do you have a favorite yourself?

FEDERMAN: Well, one of the confessions I have to make is that although I've been researching her life for 10 years, I've done very little cooking from "Honey from the Weed". I think it tends to be the kind of book that people read more than they actually use; however, it's an excellent cookbook and I have cooked a handful of recipes from it. One of my favorites actually is just a very simple pasta dish with fresh ricotta cheese, and you reserve some of the water that you boil the noodles in and mix it together with the fresh ricotta and then toss your noodles together with the cheese and the sort of starchy water, and it comes together in this just perfect sauce. A little bit of freshly grated black pepper and parmesan and you have a wonderful dish.

PALMER: Sounds delicious. [LAUGHS]

Adam Federman is a reporting fellow with the Investigative Fund of the Nation Institute, covering energy and the environment, and has written for many publications including The Nation, the Guardian, Gastronomica, and Earth Island Journal. (Photo: Adam Federman)

CURWOOD: Adam Federman’s book is called, Fasting and Feasting, the Life of Visionary Food Writer Patience Gray. He spoke with Living on Earth’s resident Briton, Helen Palmer.

Related links:

- Honey From a Weed by Patience Gray

- The Guardian: “Patience Gray’s Honey From a Weed”

- Angela Carter’s 1987 review of Honey From a Weed

- Other works by Adam Federman

[MUSIC: Ann Redgewell, “La Dolce Vita” not commercially available, traditional Italian music mandolin]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Olivia Reardon, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth