Benzene In Houston

Air Date: Week of September 29, 2017

Some of Houston’s many chemical plants and refineries suffered damage after Hurricane Harvey, releasing higher-than-normal levels of benzene and other chemicals. (Photo: Petty Officer 1st Class Patrick Kelley/Coast Guard, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In the wake of Hurricane Harvey some 40,000 pounds of carcinogenic benzene was released, much of it from a refinery in the neighborhood of Manchester. Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood spoke with ProPublica Reporter Lisa Song about her team’s investigation.

Transcript

CURWOOD: One of the toxic body burdens researchers are anxious to measure in the Houston area is the carcinogen benzene. Air Alliance Houston and the Environmental Defense Fund hired experts to look for pollutants in the wake of Hurricane Harvey, and found significant levels of benzene near a damaged storage tank at the Valero refinery in Houston. ProPublica and the Texas Tribune teamed up on this story, and ProPublica reporter Lisa Song joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Lisa.

SONG: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So, benzene. I think of it as the chemical you smell when you fill up a car with gasoline. What exactly is it?

SONG: So, benzene is what's called a Volatile Organic Compound, and the reason everyone really is focused on it is because it's one of the chemicals that we know is really toxic, and it can cause cancer, and it can be dangerous at very low levels. So, oftentimes after an oil spill or some kind of industrial accident, people are really focused on looking for benzene levels because if they're around then that's an indication that people nearby may be in danger.

CURWOOD: Why did you folks decide to look at benzene levels in the Houston area?

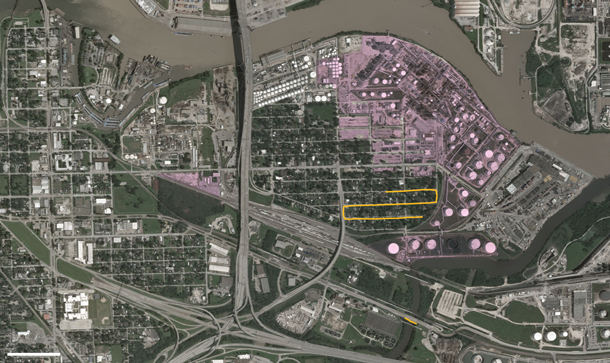

Where the private monitoring firm found high levels of the carcinogen benzene. (Photo: Al Shaw, ProPublica, with GIS work contributed by Jeremy Goldsmith. Map sources: DigitalGlobe, Entanglement Technologies, EPA)

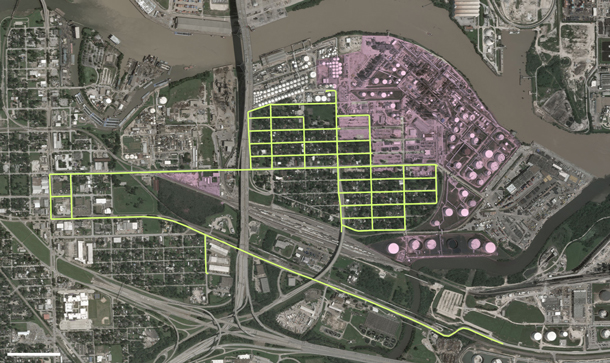

SONG: So, we know that in the days leading up to Harvey and during the storm and after, there were a number of chemical plants and oil and gas facilities in the Houston area that emitted millions of pounds of pollutants into the air. And benzene was among these pollutants. So, after the storm left Houston, there were a lot of people who came in to do air monitoring in the area, including the EPA and state officials and various university groups and private groups. But as of last week when we had written the story, none of that real data had been released to the public. All we knew was that the EPA said all of the benzene levels they had detected were under the Texas air quality health guidelines.

CURWOOD: And what's EPA's explanation for not releasing the actual numbers here?

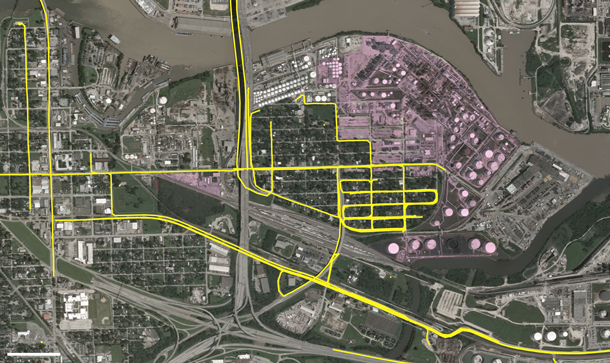

SONG: We haven't gotten an explanation. If you look at the EPA's hurricane response website, they have a bunch of different maps with information about their air monitoring, but every map simply states that all of their data shows chemical concentrations are under the Texas Health guidelines, and that's all they say. So, the real number to watch out for according to Texas health officials is 180 parts per billion of benzene in the air. And so the EPA said, “All of our measurements are under 180 so everything's OK.” But because they didn't release the actual numbers, you don't know if the measurements are just a little bit under 180 or if they're far below that threshold, and so what we ended up doing was we found out there was a private air monitoring group that had been hired by two environmental firms. And so this group had gone out and done benzene monitoring in the same neighborhood that the EPA had at around the same time, and so they gave us their data, which had real numbers and so we decided to map these numbers and write a story about them so that people actually know what they're breathing in.

CURWOOD: By the way, in your article you point out that the parts per billion of benzene that meet Texas guidelines is very different from what is recommended in California, although in both places it's not actually a legal limit – It's just guidance.

SONG: Yeah, this is one of the strange things that we don't actually have federal limits on what's considered safe for the public to breathe in for benzene. The only federal limits we have are for occupational workers in an industrial setting, and that's not the same kind of protection you would want to give the general public which includes children and infants and people who are more vulnerable. So, instead, different states set up their own guidelines for what's considered acceptable and the process for calculating those levels is very complicated. It's an expensive process. It takes a lot of scientific expertise. So, not all states are able to calculate their own numbers and when they do, they often come up with very different levels.

Where the EPA monitored. (Photo: Al Shaw, ProPublica, with GIS work contributed by Jeremy Goldsmith. Map sources: DigitalGlobe, Entanglement Technologies, EPA)

CURWOOD: Lisa, in your article you talked about the level of benzene that the petroleum industry thinks is safe, and you quote the American Petroleum Institute on that. Could you repeat that for us now?

SONG: So, there was some reporting that came out a few years ago showing that the American Petroleum Institute – which is a huge oil and gas lobby – that they had privately admitted many decades ago that the only absolutely safe concentration of benzene is zero parts per billion. And so we know that if you really want to be safe, you shouldn't be breathing in any benzene at all. But also if you use that as the standard, it's unrealistic because our cars emit some benzene into the air. So, anyone who lives in a city is going to be breathing in small amounts of benzene, and all that regulators can do is try to find a level to manage the risk because we know we can't get rid of benzene entirely in the air.

CURWOOD: Now, you reported on this independent monitoring firm called Air Alliance Houston. What exactly did they find in comparison to the Texas guidelines and the California guidelines?

SONG: So, only about 10 percent of the samples they took were above the California guideline of eight parts per billion and the highest level that they found was a single concentration of 90 parts per billion of benzene, and if you were to compare the 90 to the Texas guidelines that's only half of the 180 that Texas has set. But this 90 parts per billion, of course, is significantly above the California threshold, and this was found in the neighborhood of Manchester and it was found near an oil storage tank that had been damaged by Hurricane Harvey, and the company itself, Valero refining, had reported that due to damage from the storm there was a crude oil leak from the tank and a release of benzene from the tank.

Where the private firm monitored. (Photo: Al Shaw, ProPublica, with GIS work contributed by Jeremy Goldsmith. Map sources: DigitalGlobe, Entanglement Technologies, EPA)

CURWOOD: And your article suggests that the levels could have spiked even higher than what was recorded by researchers. Why is that?

SONG: Yes, because the data that we have were gathered about a week after the hurricane hit Houston and a few days before this data was gathered, the city of Houston did its own air monitoring, and they found a single concentration of 324 parts per billion of benzene near this refinery. So that number obviously is even higher than the Texas benchmark of 180 parts per billion and since that was taken closer to when the storm hit Houston. It indicates that in the days right after the storm Manchester was exposed to higher levels of benzene than what we have from the data that we reported on.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the community of Manchester. What kind of community is it?

SONG: So, Manchester is a community that is largely low income, and mostly Hispanic, and they are surrounded by a lot of industrial facilities like this giant refinery, like several highways and also railroad tracks.

So, this is what's called a fence-line community, meaning they're close to a lot of industrial air pollution and so they already have higher levels of asthma and respiratory illnesses and higher rates of cancer than the city of Houston at large. And so when you have an event like this kind of oil storage tank leak happen after a hurricane, it just adds to the level of air pollution they're normally exposed to.

CURWOOD: So, what did the residents there at Manchester notice that was odd about their quality or what kind of health impacts did they experience because of these higher levels of benzene?

Lisa Song is an environment reporter at ProPublica. (Photo: Courtesy of Lisa Song)

SONG: So, we've interviewed some residents from Manchester, and several of them said that they noticed a very strong chemical stench right when the hurricane hit. It's been described as smelling like glue or just an undescribable chemical smell, but these residents also say that they're used to smelling these kinds of things every once in a while. So, one resident said every few months you can smell something from the refinery or what they believe is coming from the refinery but that on the day the hurricane hit, the smell was particularly strong.

CURWOOD: What can we learn from this case study into what happens in terms of data collection after a toxic chemical emergency?

SONG: I think this is the same lesson you see every time there's an oil spill or some kind of incident, that it's always important to get into the field as soon as possible after an event and take as much data as possible, and if you really want to help the community that it's important to tell them exactly what they're breathing in. I would say it's much more informative to the community if they have real data points of exactly what levels they're being exposed to rather than just summary data as the EPA has been giving out so far.

CURWOOD: Lisa Song is an environment reporter for ProPublica. Thanks so much, Lisa, for taking the time.

SONG: Thank you.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth