September 29, 2017

Air Date: September 29, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Toxic Exposure & Hurricane Harvey

View the page for this story

As Houston area people return to businesses and homes flooded during Hurricane Harvey, researchers are gathering base line data from volunteers on their chemical exposures wearing wristbands. Melissa Bondy, a Professor in the Department of Medicine-Epidemiology and Population Sciences at Baylor College of Medicine, explained to host Steve Curwood how these wristbands and mapping of reported releases will help assess current and future health risks for victims of natural disasters. (05:38)

Benzene In Houston

View the page for this story

In the wake of Hurricane Harvey some 40,000 pounds of carcinogenic benzene was released, much of it from a refinery in the neighborhood of Manchester. Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood spoke with ProPublica Reporter Lisa Song about her team’s investigation. (09:12)

Shrinking America’s National Monuments

View the page for this story

Following a four-month review of more than two dozen National Monuments, Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke submitted confidential recommendations to the Trump Administration in August. A leaked report spotlights Zinke’s proposals to shrink a number of Monuments and open some to extractive industries like mining, grazing and fishing. Vermont Law professor Hillary Hoffman joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the legality of altering these protected and popular spaces. (06:32)

Eyes in the Sky For Nature

View the page for this story

From satellites and aircraft scientists can examine the structure of ecosystems, even their chemical properties, to determine their health. Stanford ecologist Greg Asner helped develop a system of specialized scientific instruments for aircraft, and was recently recognized for these contributions with the 22nd Heinz Environment Award. Host Steve Curwood and Greg Asner discuss how this ultra high resolution remote sensing can help inform policy to protect natural resources like carbon-sequestering forests, and how the next frontier is to put this technology into orbit. (07:57)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood discuss recent reports of polystyrene trash in ice only a few hundred miles from the North Pole, and note the steady recovery of the huge endangered leatherback sea turtle. Then they remember the mystery of the Mayak nuclear disaster in Russia. Though it was the third largest nuclear accident in history, it was kept secret for more than 30 years, and is still mysterious today. (03:16)

The Web Imperils Endangered Species

View the page for this story

The surge in data publicly available on the internet has been a boon for biological science and conservation. But it’s also being used by dishonest collectors and poachers to easily locate rare plants and animals and sell them illegally for a hefty price. Host Steve Curwood spoke with wildlife journalist Adam Welz about how the need to regulate public data and find a happy middle ground to preserve the spirit of scientific discovery while protecting at-risk species. (10:57)

Cheetah

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender gives us a glimpse into life on the Maasai Mara through the eyes of the world’s fastest feline: the increasingly threatened Cheetah. (02:59)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Melissa Bondy, Hillary Hoffmann, Lisa Song, Adam Welz

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. In the wake of this year’s deadly hurricanes, private researchers are finding high levels of benzene in a Houston neighborhood, though the EPA is saying little.

SONG: It’s much more informative to the community if they have real data points of exactly what levels they are being exposed to rather than just summary data as the EPA has been giving out so far.

CURWOOD: Also, how smartphone photos of endangered plants and animals posted on the web tip off poachers and dishonest collectors.

WELZ: As soon as data starts being suppressed and starts being held back it can cause damage to the core of biological science. On the other hand it is absolutely, blatantly obvious that criminals are using this data for nefarious ends.

CURWOOD: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[THEME]

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Toxic Exposure & Hurricane Harvey

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The trifecta of devastating hurricanes this season has been horrible for human health, with many in Puerto Rico still engaged in a dire struggle for survival with food, water, shelter and medical care in short supply. And where floodwaters have already receded in Texas, researchers are gathering data to understand the health effects of chemicals and mold released by the floods of Hurricane Harvey. Hundreds of people returning to their flood-damaged homes and businesses in the Houston area have volunteered to wear wristbands that gather evidence of toxic exposure. The wristbands and related questionnaires are then submitted to a team led by Melissa Bondy, an epidemiologist at Baylor’s College of Medicine. She joins us now. Professor Bondy, welcome to Living on Earth.

BONDY: Thank you. Glad to be here.

CURWOOD: So, what's it like to be a health professional in the middle of a disaster?

BONDY: I completely changed focus from doing my regular research to totally redirecting things at the drop of a hat to start to study the health effects of people that have been affected by Hurricane Harvey. And it's been exciting but overwhelming and bringing my staff together who don't normally do disaster-type research, and trying to understand what's going on in our community and what effect it has had on so many different communities in different ways.

Researchers are concerned that Houston residents who are returning to homes damaged by Harvey will face toxic chemical exposure, including mold from floodwaters. (Photo: Jill Carlson, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, tell me how do these wristbands work to assess chemical exposure?

BONDY: So, these wristbands are really exciting, novel, and they were developed by Dr Kim Anderson at Oregon State, and basically they're little bracelets just like the Livestrong wristbands that have been used, and what they do is they measure about 1,500 different chemicals ranging from caffeine to tobacco smoke to your cosmetics that you wear to pesticides and benzenes and a huge number of different types of PCBs and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and they put it back in a little bag that they send it to us. And so it doesn't get anything else on it so that it's really a personal exposure assessment for a seven-day time window.

CURWOOD: So, you're a health detective. What's at the top of the list of suspect chemicals for you with these wristbands?

Melissa Correa, a reporter for Houston’s KHOU 11, tweeted out photos of Baylor College of Medicine distributing wristbands to residents.

I can't wait for results! Folks in #Baytown wearing bracelets so #BaylorCollegeOfMed can study chem exposure after #Harvey. #khou11 pic.twitter.com/N0l3PQ0qYk

— Melissa Correa (@MCorreaKHOU) September 24, 2017

BONDY: So, what we've seen in the 150 or so people that we've interviewed that most of the people are telling us that they have respiratory infections, sinus infections, throat irritation and most of the things that they're reporting are upper respiratory. So, I'm not sure. I mean, because with 1,500 chemicals, which ones are the ones that are going to fall out as being relevant? What types of things would be irritating to the respiratory tract? And each of the communities that we've been interviewing people in have different types of exposures. One or two of the neighborhoods are closer to Superfund sites where there's chemicals that have been leached into the soil and probably into some of the groundwater near these homes, and the other population is living closer to where they released the floodwaters out of the Addicks reservoirs. We're also looking at mold, so maybe it's mold exposure and we're looking at some of the effects on the microbiome. So, we have multiple exposures going on here that could exacerbate the effects that we're seeing in the population already.

Kim Anderson at Oregon State University developed the chemical-absorbing wristbands. (Photo: Stephen Ward, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, not only are you going to get data about what people are exposed to now but you'll be following them in the weeks, months, years, maybe even decades ahead. What's the power of a longitudinal study like this?

BONDY: So, I've never looked at populations longitudinally that have been exposed to floodwaters, and the wristbands have never been used in a flooding situation. They've been used in other types of disasters, but not anything like this. So, we have no idea what to expect and what the long-term effects could be. You know, we only have examples of what happened with 9-11 and what happened with others and their exposures were quite different, and now many years later we're seeing lots of health problems – cancers – occurring. And you know what we're doing right now is collecting data so that we would have three, six and 12 month windows of time. In the meantime, we have to be building a repository at the same time that we start thinking about what the next phase of the research will be.

CURWOOD: Now, I know that professionally your, kind of, sub-specialty has been in cancer prevention. How helpful do you think your study would be to look at things like cancer risks from chemicals?

Dr. Melissa Bondy is a Professor and Section Chief in the Department of Medicine: Epidemiology and Population Sciences at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. (Photo: courtesy of Baylor College of Medicine)/p>

BONDY: I think it could be significant, because many of these people in several of the neighborhoods are totally exposed to many different types of chemicals. So, we're thinking that we could see cancers down the road. I mean, we don't know that yet. We want to work with other groups that are collecting air monitoring and water samples so that we can have a composite of different exposures that we'll be able to correlate with what we're collecting on the health side of it. So, it's going to take a lot of effort but there's a lot of soon-to-be publicly available data so that we can incorporate it into some of our GIS models, look at maps so that we can really estimate both personal – the area sampling and the home sampling – so that we could really have a good idea of what's going on.

We don't know what's going on in some of these other places where there was just Category five hurricanes in Florida and as well as in some of the islands and Puerto Rico and exposures that people might have. So, what we're hoping to learn can be used for other disasters that are probably going to happen in the near future.

CURWOOD: Melissa Bondy is a Professor in the Department of Medicine and Epidemiology and Population sciences at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today, Dr. Bondy.

BONDY: Thank you so much for inviting me. I really enjoyed being on your show.

Related links:

- KHOU: “Harvey victims wear wristbands to track chemical exposure”

- Melissa Bondy, Baylor College of Medicine

Benzene In Houston

Some of Houston’s many chemical plants and refineries suffered damage after Hurricane Harvey, releasing higher-than-normal levels of benzene and other chemicals. (Photo: Petty Officer 1st Class Patrick Kelley/Coast Guard, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: One of the toxic body burdens researchers are anxious to measure in the Houston area is the carcinogen benzene. Air Alliance Houston and the Environmental Defense Fund hired experts to look for pollutants in the wake of Hurricane Harvey, and found significant levels of benzene near a damaged storage tank at the Valero refinery in Houston. ProPublica and the Texas Tribune teamed up on this story, and ProPublica reporter Lisa Song joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Lisa.

SONG: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So, benzene. I think of it as the chemical you smell when you fill up a car with gasoline. What exactly is it?

SONG: So, benzene is what's called a Volatile Organic Compound, and the reason everyone really is focused on it is because it's one of the chemicals that we know is really toxic, and it can cause cancer, and it can be dangerous at very low levels. So, oftentimes after an oil spill or some kind of industrial accident, people are really focused on looking for benzene levels because if they're around then that's an indication that people nearby may be in danger.

CURWOOD: Why did you folks decide to look at benzene levels in the Houston area?

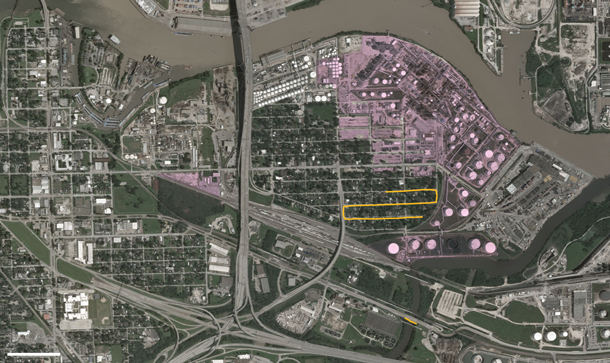

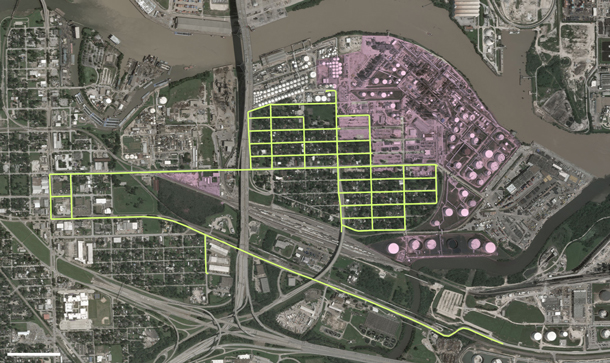

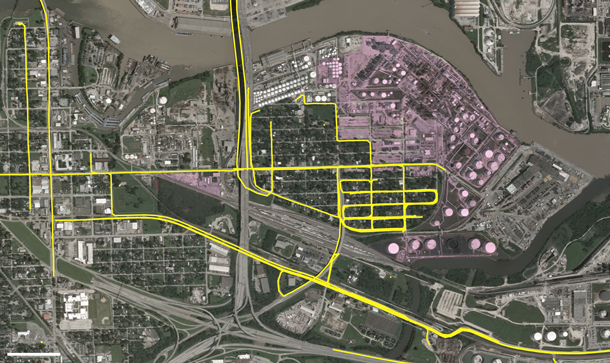

Where the private monitoring firm found high levels of the carcinogen benzene. (Photo: Al Shaw, ProPublica, with GIS work contributed by Jeremy Goldsmith. Map sources: DigitalGlobe, Entanglement Technologies, EPA)

SONG: So, we know that in the days leading up to Harvey and during the storm and after, there were a number of chemical plants and oil and gas facilities in the Houston area that emitted millions of pounds of pollutants into the air. And benzene was among these pollutants. So, after the storm left Houston, there were a lot of people who came in to do air monitoring in the area, including the EPA and state officials and various university groups and private groups. But as of last week when we had written the story, none of that real data had been released to the public. All we knew was that the EPA said all of the benzene levels they had detected were under the Texas air quality health guidelines.

CURWOOD: And what's EPA's explanation for not releasing the actual numbers here?

SONG: We haven't gotten an explanation. If you look at the EPA's hurricane response website, they have a bunch of different maps with information about their air monitoring, but every map simply states that all of their data shows chemical concentrations are under the Texas Health guidelines, and that's all they say. So, the real number to watch out for according to Texas health officials is 180 parts per billion of benzene in the air. And so the EPA said, “All of our measurements are under 180 so everything's OK.” But because they didn't release the actual numbers, you don't know if the measurements are just a little bit under 180 or if they're far below that threshold, and so what we ended up doing was we found out there was a private air monitoring group that had been hired by two environmental firms. And so this group had gone out and done benzene monitoring in the same neighborhood that the EPA had at around the same time, and so they gave us their data, which had real numbers and so we decided to map these numbers and write a story about them so that people actually know what they're breathing in.

CURWOOD: By the way, in your article you point out that the parts per billion of benzene that meet Texas guidelines is very different from what is recommended in California, although in both places it's not actually a legal limit – It's just guidance.

SONG: Yeah, this is one of the strange things that we don't actually have federal limits on what's considered safe for the public to breathe in for benzene. The only federal limits we have are for occupational workers in an industrial setting, and that's not the same kind of protection you would want to give the general public which includes children and infants and people who are more vulnerable. So, instead, different states set up their own guidelines for what's considered acceptable and the process for calculating those levels is very complicated. It's an expensive process. It takes a lot of scientific expertise. So, not all states are able to calculate their own numbers and when they do, they often come up with very different levels.

Where the EPA monitored. (Photo: Al Shaw, ProPublica, with GIS work contributed by Jeremy Goldsmith. Map sources: DigitalGlobe, Entanglement Technologies, EPA)

CURWOOD: Lisa, in your article you talked about the level of benzene that the petroleum industry thinks is safe, and you quote the American Petroleum Institute on that. Could you repeat that for us now?

SONG: So, there was some reporting that came out a few years ago showing that the American Petroleum Institute – which is a huge oil and gas lobby – that they had privately admitted many decades ago that the only absolutely safe concentration of benzene is zero parts per billion. And so we know that if you really want to be safe, you shouldn't be breathing in any benzene at all. But also if you use that as the standard, it's unrealistic because our cars emit some benzene into the air. So, anyone who lives in a city is going to be breathing in small amounts of benzene, and all that regulators can do is try to find a level to manage the risk because we know we can't get rid of benzene entirely in the air.

CURWOOD: Now, you reported on this independent monitoring firm called Air Alliance Houston. What exactly did they find in comparison to the Texas guidelines and the California guidelines?

SONG: So, only about 10 percent of the samples they took were above the California guideline of eight parts per billion and the highest level that they found was a single concentration of 90 parts per billion of benzene, and if you were to compare the 90 to the Texas guidelines that's only half of the 180 that Texas has set. But this 90 parts per billion, of course, is significantly above the California threshold, and this was found in the neighborhood of Manchester and it was found near an oil storage tank that had been damaged by Hurricane Harvey, and the company itself, Valero refining, had reported that due to damage from the storm there was a crude oil leak from the tank and a release of benzene from the tank.

Where the private firm monitored. (Photo: Al Shaw, ProPublica, with GIS work contributed by Jeremy Goldsmith. Map sources: DigitalGlobe, Entanglement Technologies, EPA)

CURWOOD: And your article suggests that the levels could have spiked even higher than what was recorded by researchers. Why is that?

SONG: Yes, because the data that we have were gathered about a week after the hurricane hit Houston and a few days before this data was gathered, the city of Houston did its own air monitoring, and they found a single concentration of 324 parts per billion of benzene near this refinery. So that number obviously is even higher than the Texas benchmark of 180 parts per billion and since that was taken closer to when the storm hit Houston. It indicates that in the days right after the storm Manchester was exposed to higher levels of benzene than what we have from the data that we reported on.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the community of Manchester. What kind of community is it?

SONG: So, Manchester is a community that is largely low income, and mostly Hispanic, and they are surrounded by a lot of industrial facilities like this giant refinery, like several highways and also railroad tracks.

So, this is what's called a fence-line community, meaning they're close to a lot of industrial air pollution and so they already have higher levels of asthma and respiratory illnesses and higher rates of cancer than the city of Houston at large. And so when you have an event like this kind of oil storage tank leak happen after a hurricane, it just adds to the level of air pollution they're normally exposed to.

CURWOOD: So, what did the residents there at Manchester notice that was odd about their quality or what kind of health impacts did they experience because of these higher levels of benzene?

Lisa Song is an environment reporter at ProPublica. (Photo: Courtesy of Lisa Song)

SONG: So, we've interviewed some residents from Manchester, and several of them said that they noticed a very strong chemical stench right when the hurricane hit. It's been described as smelling like glue or just an undescribable chemical smell, but these residents also say that they're used to smelling these kinds of things every once in a while. So, one resident said every few months you can smell something from the refinery or what they believe is coming from the refinery but that on the day the hurricane hit, the smell was particularly strong.

CURWOOD: What can we learn from this case study into what happens in terms of data collection after a toxic chemical emergency?

SONG: I think this is the same lesson you see every time there's an oil spill or some kind of incident, that it's always important to get into the field as soon as possible after an event and take as much data as possible, and if you really want to help the community that it's important to tell them exactly what they're breathing in. I would say it's much more informative to the community if they have real data points of exactly what levels they're being exposed to rather than just summary data as the EPA has been giving out so far.

CURWOOD: Lisa Song is an environment reporter for ProPublica. Thanks so much, Lisa, for taking the time.

SONG: Thank you.

Related links:

- ProPublica: “Independent Monitors Found Benzene Levels After Harvey Six Times Higher Than Guidelines”

- EPA Houston Air Monitoring Press Release

- Check out our previous interview on Harvey and toxics

[MUSIC: Clayton March with Jacqueline Schwab, “Oif’n Pripetshok” on In Klezmer, traditional eastern European, released/distributed by Clayton March]

CURWOOD: Coming up, National Monuments under fire. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ottmar Liebert + Luna Negra, “Havana Club (The Latin Mix)” on Euphoria, Epic Records Group/Sony Music Entertainment]

Shrinking America’s National Monuments

The sun sets on the Grand Staircase-Escalante national monument in southern Utah. The site is one of many that Secretary Zinke has recommended shrinking in a leaked memo to President Trump. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. After four months of reviewing America’s National Monuments, Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke delivered his confidential recommendations to the White House in August. A leaked report says Mr. Zinke wants to shrink some Monuments, and also allow greater commercial uses such as mining, logging, and fishing. Presidents can create a National Monument out of federal lands with just the stroke of a pen, thanks to the 1906 Antiquities Act, and they are just about the same as a national park. But according to Vermont Law School Professor Hilary Hoffmann, while many years ago administrations did make small changes in monument boundaries to fix surveying mistakes and title disputes, a law passed in 1976 now gives Congress the sole power to revise or eliminate national monuments. Professor Hoffmann joins us now –Welcome to Living on Earth.

HOFFMANN: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So, what's the public support for these proposals to shrink these national monuments and add some commercial activities?

HOFFMANN: The local support across the board has been for the monument designations. There's been limited opposition to the monument designations primarily from those who favor the extractive industries like mining and grazing, and these are particularly for the land-based monuments. But when Secretary Zinke put forth this review period for the National Monuments that are currently under review – and there was twenty something monuments that he was considering recommending, altering or modifying their boundaries – the overwhelming majority of public support was to keep the monuments exactly the way they are, to keep them at their current size and the current scope and not to touch the designations of the previous executives.

In July, Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke (in blue) visited the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument in Oregon as part of a review of the nation’s monuments. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Professor Hoffmann, talk to me about the politics behind this move. What does the Trump administration think it can gain by shrinking these National Monuments and allowing more commercial activity? What is the basis of this?

HOFFMANN: Well, potentially it would curry favor with some of the local interests. In Utah the delegation has been overwhelmingly supportive of mining and grazing and other extractive industries, and so this would potentially gain him some support amongst those local small contingencies that oppose National Monuments. They're described often by the local news outlets and by the local county commissioners as “federal land grabs.” And so, some in the local community feel that this is the federal government overreaching its authority and stealing land, if you will, that locals have always had access to and been able to use. And that's somewhat problematic for a couple of different reasons: one reason is that a National Monument can only be established on land that is federal land. So this was already federal land, it's just that the level of protection was slightly increased from what it was before, and National Monuments absolutely preserve access. So, if people are worried about being able to access these public lands, they can still use them after the National Monument designation is in place, it's just that the management is going to be a little bit more careful.

CURWOOD: So, there's money for commercial interests if Grand Staircase Escalante or Bears Ears or both weren't National Monuments?

National Monuments are designated by presidents for their historic, cultural or scientific importance to the country, and not all of them are composed of vast wilderness. The Statue of Liberty was designated as a national monument in 1965. (Photo: Fredrik Rubensson, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

HOFFMANN: Sure, well, of course, there's money any time you're talking about extracting mineral resources from the public lands and there might be limited job creation in the near term, but the federal government subsidizes those extraction programs so heavily that the American public isn't reimbursed for the cost of the fossil fuels that are extracted. Economists have studied National Monuments and their impact on particularly rural western economies and National Monuments have a very positive impact on rural western economies, so a lot of business owners and small towns in southern Utah favor and support the continued existence of these National Monuments because they bring tourists to their doorstep.

CURWOOD: Why doesn't the Trump administration take this to Congress as the law provides that Congress could shrink or even rescind these National Monuments? You've got a Republican White House, Republican Senate, Republican House of Representatives. Why not go the legal route?

HOFFMANN: Well, it's not clear to me that President Trump won't do that, so it's possible that President Trump will take this to Congress and legally speaking Congress does have the power to do what the Trump administration seems to want to do with these Monuments. But certainly Executive Action, unilateral presidential action is faster. It accomplishes the purpose more quickly. The problem is that the resulting litigation would bog down the courts for years to come, so there are plenty of interest groups who support these National Monuments that are gearing up for litigation, if Trump decides to unilaterally abolish or reduce any of the National Monuments.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about how if at all National Monument designations in the past have sought to address inequities faced by Native Americans, the first Americans in this country.

Hillary Hoffman is a professor of Law specializing in Natural Resources Law and Management, Administrative Law, Climate Change and Native American Law at the Vermont Law School. (Photo: The Vermont Law School)

HOFFMANN: Well, that's such an important question because so many of the public lands and the places that have been protected by Congress since the nation's inception were the aboriginal homelands of Native American nations, and so, many of the places that are culturally important and sacred to these various tribes are located on public lands and are outside of the tribes' homelands today. So, for tribes like the Navajo and the Hopi and the Zuni and the Ute in Southern Utah and Northern Arizona, the Bears Ears region has really important cultural and historic ties for those tribes and President Obama recognizing those ties in the establishment of Bears Ears National Monument is really a significant step forward in acknowledging the place of Native American nations in this country's history.

CURWOOD: So, if the President were to accept these recommendations as they currently exist, what kind of response might we see to this, from environmental groups, from the Congress, from the public do you think?

HOFFMANN: I think there will be a lot of public outcry. I think the public overwhelmingly supported the continued existence of all of the Monuments that were subject to the Secretary's review. There will definitely be litigation. There are plenty of, business alliances and organizations that will inevitably bring lawsuits challenging whatever actions President Trump decides to take.

CURWOOD: Hillary Hoffmann is a Professor of Law specializing in Natural Resources Law and Management, Climate Change and Native American law at the Vermont Law School. Professor Hoffmann, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

HOFFMANN: Thank you.

Related links:

- Vermont Law School

- NYTimes: “Here Are the 10 National Monuments the Interior Department Wants to Shrink or Modify”

- Washington Post: Why Americans are fighting over a gorgeous monument called Bears Ears

- Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976

- National Park Service: the Antiquities Act of 1906

[MUSIC: Solomon (The Solomon Band), “Not Life Threatening” on Not Life Theatening, Storm Records]

Eyes in the Sky For Nature

The Carnegie Airborne Observatory in action, flying above the “patch reefs” of Hawaii’s Kaneohe Bay. (Photo: Carnegie Airborne Observatory)

CURWOOD: High-tech, remote imaging developed for the military is also now a powerful tool in the hands of scientists studying the health of ecosystems. Remote forests and coral reefs can be assessed from satellites, and specially equipped aircraft can get an even closer look, down to individual branches of trees. Greg Asner, Principal Investigator at the Carnegie Institution’s Global Ecology Lab at Stanford helped develop an ultra-high-resolution imaging system for aircraft that won him the 22nd Heinz Award in the Environment category. He joins me now. Greg, congratulations and welcome to Living on Earth.

ASNER: Thank you for having me. It's great to be here.

CURWOOD: Hey, let's start by talking briefly about this plane that you've tricked out with a lab inside. It's this short takeoff and landing machine called a Dornier 228, I think. Now, usually if you've got one of those you're like out in the middle of nowhere and they roll it up to fly you from one remote location to another, like maybe 20 seats. But what do you have in one?

ASNER: Right, what we've done is we've gutted the plane down to the skin and the shell of the plane, and then we built back up a high tech laboratory inside. Think aluminum, carbon fiber, think lightweight materials, and also think instruments and supercomputing capability onboard.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the instruments that you put in there. I think you have an acronym, ATOMS. What does ATOMS stand for?

ASNER: ATOMS is a name that I gave to it back when we first built the system. It stands for Airborne Taxonomic Mapping System. ATOMS is comprised of a suite of instruments that work together. One of the instruments is a laser scanning system. We fire laser beams out of the bottom of the plane, and those lasers interact with the land, the trees, whatever we’re flying over. Those lasers give us a three-dimensional view of the ecosystem. That would be how tall are the trees. What's the architecture of the branches? And it tells us about even the leaf-level architecture. And then we have other instruments that work with that. Some of those are called imaging spectrometers, and for that we use sunlight that bounces off of, for example, the tree canopy and we can measure the chemical composition of those trees as we fly over with those spectrometers. And finally we have some high-resolution cameras that allow us just to collect the background information about, you know, what did we do that day, what did we fly over. It gives us a reference.

CURWOOD: So, tell me what kinds of features of the landscape can you image with this technology?

ASNER: We've been focusing on forests. We're using our technology to understand the composition of the forest. When we say composition, we're talking about how much biomass is there. We're also talking about how many species are there per acre, and we're also talking about the health of the forest, so how much water is in the tree canopy, nitrogen, the building blocks of life. Lately, we've also been doing that with coral reefs, and we just had a breakthrough last year where we figured out how to fly over a coral reef and digitally remove the seawater so that we exposed the bottom and we were able to understand the health and the condition of the corals that live below that sea surface.

CURWOOD: Where have you mapped in the world so far?

ASNER: Well, we've been all around the planet. The places we've put our most emphasis have been on regions that are undergoing rapid development. We think that our science and our technology can play a role in mapping, for example, the attributes of a forest in a way that allows for better decision-making in the context of development, in the context of, say, putting in new agricultural fields and avoiding areas of high biodiversity. We're good at mapping where is that biodiversity and then helping governments make decisions about how best to develop around it. We also work on National Park development and other types of protected areas. All of that work has been in Latin America, Central America. We're just now finishing a big project in Southeast Asia, in the country of Malaysia. Lots of work in South Africa, Madagascar, you name it ... dotting the planet all the way around, but really focused in developing regions.

Greg Asner is Principal Investigator at the Carnegie Institution for Science’s Global Ecology Lab and recipient of this year’s Heinz Environment Award. (Photo: Spencer Lowell)

CURWOOD: Briefly, what have you found?

ASNER: Well, I call it the good, the bad, the ugly. We found extremely high biological diversity, and what that means is lots and lots of species coexisting in patterns that were unknown to science. And so, you know the good thing is that we're able to unveil those landscapes and see them for the first time. The bad would be when we our work reveals that there are, say, illegal gold miners in a region and then the ugly is some of the hardest work we do which is mapping regions in preparation or in consultation for the effort to mitigate losses as climate change proceeds. I call that ‘the ugly’ because those are really hard problems to crack. That science is in its infancy and we're still trying to figure out how to do it.

CURWOOD: Greg, a key reason that the Heinz award has been the one given to you this year for the environment is because your research has helped inform some policies and enforce some existing laws. Please, give us some examples of how that's worked, in California and in Hawaii, as I understand it.

ASNER: Yeah, well, in California we've been working closely with state and federal government agencies. We got into the process of flying the forests of California, working with agencies, and helping them understand the impacts of the mega-drought that we just went through. That work that we did, and it continues today, has helped the state government understand where to put people on the ground, for example, fire mitigation, watershed management, and biodiversity protection with the National Parks and with the state parks.

In Hawaii, we're working heavily on coral reef, we're looking at the recent bleaching events from the hot water that's come into the region and also other issues that have crept up as fine a scale as the types of sunscreens people are using. They put it on their bodies, and they go swimming and some of those sunscreens are extremely toxic to coral reefs.

CURWOOD: How useful is your technology to understanding the carbon flux, the carbon balance in forests and other ecosystems?

ASNER: That's been where a lot of our work has focused over the years. Some of our most operational, mature type of science is the issue of how much carbon is stored in any forest that we fly over. Today, we're able to fly over a forest and relatively quickly get an estimate of the carbon stock, and that's important for a lot of reasons. One, carbon is a great metric of the health of a forest. A forest with lots of carbon stored generally is a forest that's in good shape. But also, it's a critical component of the climate change mitigation efforts of state and federal governments. They want to be able to store carbon in forests rather than it being in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, so they want to know how much they're storing in these forests today and they want advice and consultation and guidance on how they might store even more carbon in their forests in the future.

CURWOOD: Greg, what's going on in terms of federal funding to support the kind of work that you're doing, especially advancing it to the level of flying satellites that might be able to get the same information that right now you have to kind of bump along in the prop plane to get.

The Carnegie Airborne Observatory can fly over a forest and capture detail down to the branch structure and even individual leaves. (Photo: Carnegie Airborne Observatory)

ASNER: [LAUGHS] There have been great efforts within NASA to put some of the technology into orbit. There is a pathway to get the laser technology up onto the space station. We should see that happening, I think, about a year and a half from now. The chemical mapping is the most critical at this point in terms of mapping the health of coral reefs and ecosystems in general on land and in the sea. Those technologies are of interest to organizations like NASA and the federal government side, but I think that some of the demand hasn't been clear enough to really put it into orbit. But at the same time I'm very happy to see the philanthropic and the commercial sector stepping up to want this technology to go into orbit. It might be that we get to orbit first via those non-government pathways. I'm working all of them trying to find the fastest way to get up there.

CURWOOD: Greg Asner is principal investigator at the Carnegie Institution's Global Ecology Lab based in Stanford, California, and recipient of this year's Heinz environment award. Congratulations.

ASNER: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- The 22nd Heinz Environment Award: Greg Asner

- Greg Asner’s TED talk, “Ecology from the air”

- About the Carnegie Airborne Observatory

[MUSIC: Ottmar Liebert + Luna Negra, “Havana Club (The Suspended Mix) on Euphoria, Epic Records Group/Sony Music Entertainment]

CURWOOD: Coming up, mapping endangered species can help save them, but big data is also putting them at risk. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ottmar Liebert + Luna Negra, “Havana Club (The Suspended Mix) on Euphoria, Epic Records Group/Sony Music Entertainment]

Beyond The Headlines

In the Arctic spring, ice melts, revealing any solid debris trapped in the winter. Scientists recently discovered sizeable chunks of plastic waste on ice only a few hundred miles from the North Pole. (Photo: NASA Ice, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Time now for a look beyond the headlines, with Peter Dykstra, on the line from Brookhaven, Georgia. Peter’s with Environmental Health News, EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. An international research team reports finding what they call "sizeable chunks" of polystyrene in the melting ice only a few hundred miles from the North Pole.

CURWOOD: Gee, that makes something of a something of a clean sweep – or maybe I should say a dirty sweep – of the world's oceans.

DYKSTRA: Dirty sweep indeed. With plastic patches floating in all the world's oceans, the Great Lakes too, and the Great Pacific Garbage Patch now said to be the size of the nation of India, our love of plastic products and plastic packaging is coming home to roost.

CURWOOD: And I guess there's really no solution for the literally billions of tons of plastic from tiny microbeads to fishing driftnets, so I hope you can offset that news with some good news today. What do you have next?

DYKSTRA: Well, I do have some good news involving one of my favorite animals: leatherback turtles, and their sea turtle cousins. Not to postpone the good news, but let me tell you about leatherbacks. They’re awesome because they're huge – they’re the biggest sea turtle species, with dark, leather-like shells with white stripes that make them look like marine Volkswagen beetles.

A hatchling leatherback sea turtle surfaces from sand on the Florida coast. Efforts to protect and replenish wild populations are proving successful. (Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: OK, and the good news?

DYKSTRA: Efforts to save turtles by changing fishing nets, revised fishing methods, decline in sales of turtle shells for jewelry, and creating protected and darkened beaches for egg-laying are working, says Antonios Mazaris, who studies sea turtle mortality for Aristotle University in Greece.

CURWOOD: Well, that is some surprising good news given the assault on our beaches and oceans. Hey Peter, finally, as always, what do you have for our weekly trip through the environmental archives?

DYKSTRA: Well, sixty years ago this week in Russia's Ural Mountains, there was an explosion in a radioactive waste storage tank near the nuclear weapons complex at Mayak. Sixty years later, all the details still aren't known – the rest of the world didn't know Mayak existed, and the towns built to serve the complex couldn't literally be wiped off the map because the Soviets had never actually put them on the map in the first place.

CURWOOD: So you’re telling me that Mayak and the communities surrounding it weren't known to the rest of the world?

DYKSTRA: So secretive was this whole operation – it was a key site for Russia's building its own H-bomb – that Mayak wasn't even known to other Russians. There's no formal death toll, we know little about the fate of the towns around Mayak. The first real info on the accident came from a Russian dissident scientist, Zhores Medvedev, nearly two decades later. Apparently, the waste storage tanks contained ammonium nitrate.

The Ural Mountains in Central Russia are home to the Mayak Nuclear Facility. In 1957, the site experienced one of the worst nuclear accidents ever in history, but Russian officials kept it secret for more than three decades. (Photo: Aleksandr Zykov, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Uh, I think that’s the stuff, it’s fertilizer and it was used to blow up the Oklahoma City Federal Building in 1995.

DYKSTRA: Absolutely correct, but, mind you, this was radioactive ammonium nitrate. To this day, information on the Mayak disaster is still sketchy, though it's believed to be the third largest nuclear accident in history, following the two nuclear power plans at Chernobyl in the Ukraine in 1986 and Japan's Fukushima disaster in 2011.

CURWOOD: Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and DailyClimateorg. We’ll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: OK, Steve, thanks a lot, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- The Guardian: “How did that get there? Plastic chunks on Arctic ice show how far pollution has spread”

- Denver Post: “Huge sea turtles slowly coming back from brink of extinction”

- Concord Monitor: Russia’s nuclear nightmare flows down radioactive river

[MUSIC: Clayton March with Jacqueline Schwab, “Boyberiker Hora” on In Klezmer, traditional eastern European, released/distributed by Clayton March]

The Web Imperils Endangered Species

Matilda’s Horned Viper is a newly-discovered snake species with a small natural range that leaves them vulnerable to poachers. (Photo: Tim Davenport/Wildlife Conservation Society)

CURWOOD: The Internet can help you locate everything from a popular restaurant in a strange town to the start of a remote hiking trail, but location data published online about endangered species might just put them in harm’s way. Whether it's a scientific study in an online database or a simple cell phone photo of a rare species posted on Facebook, the explosive growth of data is fueling a vast illegal trade of small plants and animals. And according to South African writer, photographer, and filmmaker Adam Welz, many people don’t seem to know or care about the problem. Mr. Welz just published an investigation with Yale E360 about this topic and joins us now from south of Cape Town. Welcome to Living on Earth, Adam!

WELZ: It's very good to be on this very interesting show.

CURWOOD: Hey, how did you become interested in the ways poachers and collectors use public data?

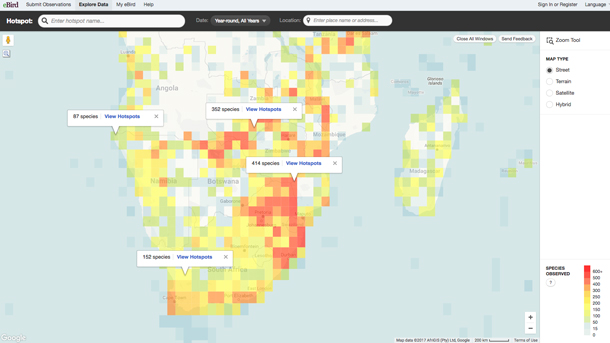

WELZ: Well, I've been interested in data for quite a long time. Even though I'm a journalist, I have a degree in ornithology and I've been interested in science, and I've also been a very keen user of various new apps that allow people to crowd source all kinds of data about wildlife, like for example, eBird, which allows ordinary bird watchers to contribute data to scientific studies by logging the birds they see when they go out bird watching. I read a few things and I heard a few things from scientists that I know, and it dawned on me that there is an enormous amount of geospatial data in the world at the moment, and it's accumulating at a rapid rate. By geospatial data I mean data about where wild species are in space and time. And I thought, man, this is really interesting because it allows us to do all this amazing science, but there's a dark side to all this data which is that poachers and people who are up to no good are increasingly using it to find their "prey" shall we say.

CURWOOD: So, what you're telling me if I were to be in the in the woods of southeast in the United States and think I had found an Ivory-billed woodpecker which has been thought to be extinct since sometime in the 1940s, I should not go and put that on eBird, huh?

WELZ: You probably should not go and put that on eBird. In general, I think if you find something that's truly special, you should give the information to somebody of great credibility, somebody perhaps who works for a well-established organization that's out in the public eye, and then keep an eye on them, too, because some of the most professional poachers and smugglers are experts in their field, are university professors. Then we also have international traders. These are people who don't necessarily know as much about the animals that they're trading as the specialists, but they move around the world picking up animals to order for their clients, again, who are these collectors who might be interested in a particular group of species, and then the third crowd in this game are the criminal syndicates, and these are the seriously organized criminals who are often dealing all kinds of other things. They're dealing illegal drugs, they're dealing guns, they're in human trafficking, and they're dealing endangered species as well because that is just another way of making money for them.

Argyroderma theartii, a succulent variety found in Knersvlakte reserve in South Africa. (Photo: Martin Heigan, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, when did this become a problem?

WELZ: There's no specific point at which this became a problem. This has progressively become more of an issue as the internet has grown, and as these databases have grown, and as people have started to more and more see the potential of sharing data either formally within the scientific community or informally among ordinary people on social media about nature. So, this is a problem that's built up over time and there are all these different streams of it, if you like. There is data, as I say, that has been acquired by scientists using interesting tracking devices. Those types of tracking technologies have become more and more sophisticated. Today, we can track, literally track tiny little honeybees with tiny little electronic tags. We can track blue whales with satellite tags.

CURWOOD: Wait a second. You can put a locator on a honeybee?

WELZ: You can in fact put a tiny locator on a honeybee. People are doing this exactly today. You can implant a tiny little transmitter in a snake, for example, that will not only tell you where the snake is, it will tell you what temperature the snake is at. It will tell you perhaps the altitude of the snake. All this kind of stuff, the technology is exploding, and like I said it's being adopted very rapidly because it gives biologists and conservationists such incredibly useful data.

CURWOOD: You know, we think about the illegal animal trade, we're thinking about the dramatic images of poached elephants or rhinos or the such, but you're telling me there's a whole network of traders and collectors who are interested in smaller species and people don't seem to be as concerned.

WELZ: Yeah, I think it's very easy to sell concern for elephants and lions and rhinos compared to concern for lizards and beetles, for example. I mean, here in South Africa we have a group of beetles we call Colophon beetles. These are very rare beetles that occur in very specific localities at very specific altitudes in very small areas. There's a huge international market for dead Colophon beetles for people to put in their collections. People pay $50, $100, even a lot more sometimes for a little beetle. People will pay a $1,000, $2,000, for certain South African lizards, for example, and it's very much more difficult if you're a campaigner to get people excited about a little beetle which might actually be far more endangered, far rarer than a White rhinoceros, for example. It's very hard to relate to this tiny little bug and it's very hard for people to comprehend how much danger some of these species are in.

CURWOOD: What's the government response like in some of the countries where traders venture in terms of how they enforce the laws regarding these species?

eBird is a community platform and online database used by nature enthusiasts to trade information on bird species. (Photo: eBird)

WELZ: I would say for smaller species almost universally law enforcement is dreadful. There's no political capital to be gained particularly by saving a lizard or some obscure plant that people have never heard of. So, when people get caught in airports with a few lizards sewn into the waistband of their pants, which happens surprisingly often, you'll find that the customs officials more often than not will just perhaps confiscate the lizards and turn a blind eye and let the guy go on the way because it simply isn't worth the paperwork for them to follow up on it. Whereas, if he was carrying a gun or some drugs or some explosives, well, that would be a completely different, different story. So, that's the difficulty that we face with these species.

CURWOOD: What is the risk of certain species getting wiped out of their natural habitats entirely because of the easy access of the public now to know where they are?

WELZ: Yeah, I think that is a real concern. Here in Southern Africa, and it's the same in some other very biodiverse countries. We have a lot of species, wild species, that only occur in very, very restricted areas. So, we'll have little succulent plants, for example, which are only found in a few acres, three or four acres, and the entire global population of this plant is in that area and there may only be a few dozen of these plants. It's extremely easy for a savvy collector to come in and wipe out an entire species in one day, and we think it may actually already have happened with a succulent plant species that we know of. A particular Japanese professor came to South Africa some years ago and seems to have taken the entire population and was later found to be selling these plants for hundreds of thousands of dollars each in Japan because, of course, he had the monopoly on the distribution of that species if you like. He quite probably had every single one, and it possibly took him less than a day to take them all.

CURWOOD: Tell me what biologists have expressed to you about where they stand on this issue of this public data that can lead to endangered critters and plants.

WELZ: Biologists are extremely divided around what to do about this geospatial data because it is extraordinarily valuable to science and to conservation. There is absolutely no dispute about it. You know, we're able to do the most incredible stuff with this data and the whole of science rests upon transparency. I mean, the entire scientific endeavor is based on the idea of transparency, is based on the idea that I can replicate the results you claim to have found in your study and your experiment. And as soon as data starts being suppressed and starts being hidden and starts being held back, it can cause damage to the core of what we're trying to do when we do biological science. So, there's a lot of scientists that are really concerned about that. On the other hand it is absolutely, blatantly obvious to everybody around that criminals are using this data, and there is also some evidence that holding the data back works.

Adam Welz is a South African wildlife journalist. (Photo: courtesy of Adam Welz)

A few years ago scientists working with the Wildlife Conservation Society in Tanzania discovered a new species of viper, a very attractive little snake, black and yellow snake, which was only found in a very small forest patch in that country. And they actually published its formal scientific description without its location, and I've just checked in with those guys and they say, “You know, there's absolutely no evidence that the poachers have actually found this species yet.”

CURWOOD: So, what can you see in terms of a middle ground then that balances the risk of public data and the benefits to scientific progress and the question of having, say, formal restrictions?

WELZ: So, I mean the thing that's interesting about this is we have no international standards for holding back or releasing this data. Certain institutions have a certain set of rules. Certain researchers have their own personal rules. Some countries even have rules, but they don't line up with other countries' rules, and I think we should have an international conference about this honestly. I think people should sit around for a good period of time, people who use the data, people who accumulate the data, data experts on wildlife crime should sit around and come up with a much more comprehensive set of, let's say, guidelines that we have at the moment.

CURWOOD: Adam Welz is a science journalist with Yale Environment 360. Thanks so much, Adam, for taking the time.

WELZ: Thanks very much.

Related links:

- Yale E360: “Unnatural Surveillance: How Online Data Is Putting Species at Risk”

- Follow Adam’s work on Instagram

[MUSIC: Michael Hedges, “Aerial Boundaries” on Aerial Boundaries, Naked Ear Music/Windham Hill Records]

Cheetah

A cheetah appears in the field. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: The Cheetah is renowned for her grace, her beauty, and her speed. She’s slightly built, and not nearly as strong as the other great cats, but she can run as fast as 75 miles an hour in short bursts and that’s her main advantage. But if you are born to run, you need the space to do it. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender says that throughout Africa the land is being fenced in. Still, Mark managed on several occasions to observe and delight in cheetah and her ways.

Cheetah © 2016 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

LENDER: Out in the valley of the Maara, Cheetah is ready to rise. Yawns. Turns over belly up. Tucks her paws, cat-like, against the fuselage of her chest. That tail that is the length of her from hip to shoulder curls, and unwinds. And with the weightless grace of all her kind rolls, onto her paws and strolls into the evening, that is day to her.

Plotting its next move, a cheetah perches on a termite mound. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Hidden in the tall grass is a termite mound. She knows the place. Has used it before. Looks back. Looks again (to be sure no one is watching) and in her long legged stride, climbs the steep sides and sits, head high, unblinking.

In these flat lands height is mountain and redoubt. Vantage point is safety. Line of sight, command. Seeing first determines who will eat today and who will not and whom among the seen … will be eaten. The crocodile at water’s edge pretending to be stone; leopard dropping from an overhanging limb without a sound; lion stalking close and stealthy on the plain, for each and every one of them the eye is life or death.

With Cheetah? The eye alone is not enough. Like light itself, Cheetah is a thing of speed! Speed is Cheetah’s second sight. Speed in short bursts is her edge, bright and sharp. Her claws wear, dulled and blunted to the stubby nails of a dog. Her jaws are weak, just wide enough for the small things she can run to ground. With Cheetah, that chase is everything.

A sleepy cheetah yawns amongst the grasses. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Cheetah owls her head: One side. The other side. Back again, searching. Nothing found she takes her time, stretches as she climbs down (hind legs and tail in the air, her belly low). Blade thin, she slips into the night like paper through the slot.

At a distance her head appears again, a spotted mask of light and dark, her stare as orange as the afterglow, her eyes unwavering.

The land turns black and white.

The grass whispers.

Cat … vanishes.

CURWOOD: And for photos and more, slip on over to our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Mark Seth Lender’s website

- Mark Seth Lender’s fieldwork in the Maasai Mara was made possible by Donald Young Safaris

[MUSIC: Oranj Symphonette “The Pink Panther” The Oranj Symphonette Plays Mancini . by Henry Mancini, 1996 Rykodisc]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Olivia Reardon, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Special thanks this week to Donald Young Safaris. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can find us anytime at LOE.org – and like us, please, on our Facebook page – it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth