Humpback Whales Rebound

Air Date: Week of June 22, 2018

Ari Friedlaender deploying a motion-sensing and video recording tag on a humpback whale in Andvord Bay, Antarctic Peninsula. Collected under NMFS and ACA permits. (Photo courtesy of Ari Friedlaender)

Nineteenth century commercial whaling killed the vast majority of whales, but some species are coming back, especially humpbacks. Melting Antarctic ice has led to an abundance of krill, and with all that food humpback whales are thriving with high rates of pregnancy. University of California – Santa Cruz Researcher Ari Friedlaender tells Host Steve Curwood the comeback should be celebrated as a conservation victory, but there are questions about how long the krill boom might last.

Transcript

CURWOOD: While the ice melting in Antarctica poses a threat to coastal cities, there is at least one species that so far is benefiting. The population of humpback whales is flourishing these days, with a baby boom, or should I say, calf boom. It’s all related to the shrinking of the floating ice shelves off Antarctica, as Ari Friedlaender at UC Santa Cruz has found. He joins us now – welcome to Living on Earth, Ari!

FRIEDLANDER: Thanks a lot. Thanks for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, you're telling me there's some good news for whales. What exactly did your team find out about the humpback whale populations?

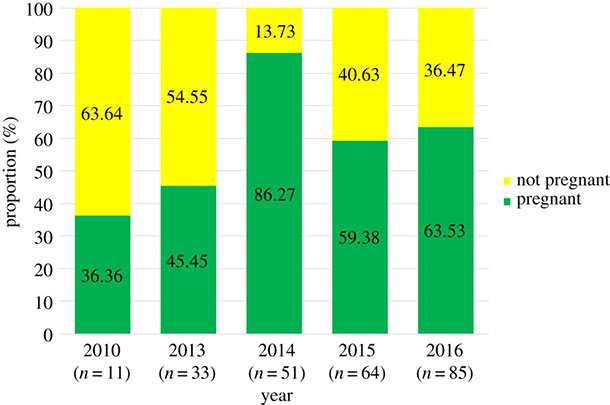

FRIEDLANDER: This was a project that we did in the Antarctic on the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula, that area that is below South America, and over a five- or six-year period what we did was to collect small skin samples from as many humpback whales as we could, and we used those samples to determine how many females in the population were pregnant each year. And what that is a good indicator of is population growth. And so what we found was that there were really high levels of pregnant females in the population in every year of our study, and that to us is a good indicator that this population is growing.

CURWOOD: So, what's a high level of pregnancy?

FRIEDLANDER: Oh, I think on average we had over 50 percent of the females in the population were pregnant in any given year, and I think in one year we had over 70 percent of the animals pregnant as well.

UAS image of two adult humpback whales in Andvord Bay, Antarctic Peninsula. The whale at the bottom is carrying a motion-sensing tag. Collected under NMFS and ACA permits. (Photo: Duke Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing Lab)

CURWOOD: And generally how often do humpback whales get... should I say, knocked up?

FRIEDLANDER: [LAUGHS] You can, yep, um… [LAUGHS] In other populations around the world, typically two or three years is the interval between having a calf, and it takes the animal that long just to be able to grow a calf and then wean it. In the Antarctic, one of the things that we found was that we had some humpback whales that were reproducing annually. So, these would be humpback whales, 40-45 feet long, weigh about 40 tons, lactating, and growing a calf inside them at the same time, which is an extremely energetically costly thing to do, and something you really can only do if you have almost an unlimited resource in terms of the availability of food.

CURWOOD: So, what is the significance then of these increased pregnancies and therefore the increased humpback population?

FRIEDLANDER: You know, the significance is that about a hundred years ago, humans in the commercial whaling industry in the southern ocean killed over two million baleen whales. And these are staggering numbers. There is a void of baleen whales in the southern ocean at this point, and since the cessation of commercial whaling in the 1980s, where effectively we're now leaving those animals alone – what this shows is that if you do leave some of these populations alone they do have the capacity and the ability to rebound. And we should be hopeful and optimistic at some level that we can reverse some of the things that we did that were so detrimental to these animals.

CURWOOD: Remind folks which whale species are baleen whales.

FRIEDLANDER: So, the baleen whales are the largest of the whales – the blue whale, the fin whale, humpback whale. These are called baleen whales because of the way that they feed. Instead of having teeth, they have these bristles or these sheets of baleen in their mouth which is made up of keratin – same thing that our fingernails are made of – and so what they do is they take in a huge volume of water that's got a lot of very small either crustaceans or small fish in it, and then they use a really massive tongue to push that water out of their mouth. And the baleen acts like a sieve and it keeps all the small food items inside.

CURWOOD: So, you know this information from samples of humpback whale skin. How do you get some humpback whale skin?

FRIEDLANDER: [LAUGHS] Yeah, it's um…. It’s an interesting process, and it's actually pretty fun. We have crossbows that we use and we have a very specialized tip on the end of that crossbow that's about the size of a pen cap and it's hollow in the middle, and we shoot a small dart at the whale. We hit it on the back up near the dorsal fin. The tip of the dart goes in about an inch, maybe an inch and a half, and pulls out a really small sample of skin and blubber, and then that that sample floats at the surface. And the bolts – we collect it, we put it into a vial, and then we freeze that until we get back to our laboratories. And then we do a pregnancy test that's based on the hormone progesterone, which is the same hormone that we have as humans that's a good indicator of pregnancy.

CURWOOD: If somebody shot a bolt into my back and took out an inch of flesh, I'd be saying, “ouch!”, maybe even louder than that. How do the other whales feel about this?

FRIEDLANDER: It's interesting. We see a variety of responses, but none of them are ever more than just a very transient... you know, it might act like it wasn't expecting to get touched or it might be like when you get bit by a mosquito. It's a very small thing relative to the size of the animal, and in fact, the animals tend to react more if we miss them, and the sound of the bolt hitting the water startles them even more so than when we take a sample.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about what it's like to conduct research in the Antarctic.

FRIEDLANDER: It's a unique place. One of the biggest challenges I have is to describe the Antarctic to people. It's an incredibly foreign and hostile place. I mean, if we aren't on a big research boat, we're not going to survive down there. So, it's incredibly hostile, but it is also the most magnificent and beautiful and just pristine area. Seeing the animals that live down there, the penguins and the whales, all of the seals and the enormity of the glaciers and the cold of the ocean and the ice around you, it gives you this sense that there are parts of this planet that are wild and that are just not suitable for people to be, and so you feel very small. It’s very humbling. But it's an incredible place, and I feel incredibly fortunate to be able to work there.

UAS image of a mother and calf pair in Andvord Bay, Antarctic Peninsula. Collected under NMFS and ACA permits. (Photo: Duke Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing Lab)

CURWOOD: Talk to me about why you think there were so many pregnant females, and, even more than that, ones nursing at the same time they were pregnant. What do you think is the cause of this whale baby boom?

FRIEDLANDER: You know, I think the cause of this – what we're calling this whale baby boom is – it's got a couple of different reasons, some good and some maybe not so good. The good is that these animals are simply reproducing very quickly because when we took out all of those whales in the last hundred years, there was this void of krill predators and so these whales are responding to the availability of food that was left over by all the whales that weren't there, and they're showing, or we're showing, that these animals have the capacity to rebound and come back to these places. The bad thing, unfortunately, is that the Antarctic peninsula is warming faster than almost any other place on the planet, and the way that that is manifesting is that there are less and less days that are covered by sea ice. So, in a given year you might have winter that comes a month later, and spring that comes a month earlier. So, for an animal that feeds on krill – and these whales don't go into the sea ice – that might mean that you have about two months greater time that you can be down in the Antarctic feeding, and that's exactly a way to translate food into energy, which means you can reproduce quicker. So, it may be that climate change is actually increasing the number of days for these whales to be able to forage and therefore to gain energy and reproduce.

CURWOOD: But?

FRIEDLANDER: That may not be a good thing for the ecosystem that's evolved down there to live on ice. The krill that these animals feed on are evolved so that they feed on the undersea ice community in their first year, and so without sea ice the first year’s worth of krill each year may not survive, or it may be a much diminished amount of krill that's available the next year. That then has consequences because eventually those krill will be the cohort that reproduces, and if there's not a lot of them to reproduce, it's a very quick step down in terms of how much food is available for all the krill predators, and then you limit how many animals might actually be able to subsist on that krill. So, while right now it might be a very good time to be a humpback whale, in the future, once the changes that are happening affect the amount of food that's available for them, it's going to limit how many animals can be there.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think we're looking at a whale bubble?

FRIEDLANDER: That may be a really good way to put it. I think for things like minke whales, which are the small endemic species that lives in the sea ice, they're going to have to find a different place to live and they're going to be forced out. There's going to be a lot of humpback whales, hopefully things like blue whales and fin whales will also increase, but there is going to be a carrying capacity that gets met. The other thing is that in nature when resources become limiting, you have competition, and it may be that humpback whales are going to compete with the penguins or the seals or the other things in the Antarctic that rely on krill as a main food source. And nature has a way of sorting those things out, and it typically means there's going to be winners and losers.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about the other whale species aside from the humpback that at this point benefit from less sea ice.

FRIEDLANDER: Right now in the Antarctic, the humpback whales are really the only ones we can measure this in, because fin whales and blue whales have not responded in an appreciable way to the cessation of whaling. One of the things that makes humpback whales so capable of reproducing quickly is because they have a very centralized breeding ground. There's a lot of places up and down the coasts of the U.S. and Australia and South Africa and South America where people know humpback whales go to breed. So, it's a lot easier to find a mate if everybody goes to the same place. For fin whales and blue whales, we don't think that there are these centralized breeding grounds where all the animals go and aggregate, so if your population levels get depressed like they have been, finding a mate can be a very hard thing.

CURWOOD: So, I take it whales don't have social media.

FRIEDLANDER: They don't have social media, absolutely not, but they can communicate across really big distances because of how loud and low frequency some of their calls are, but even with that it can be hard to find another mate in a pretty big ocean.

CURWOOD: Hey, Ari, tell me – what are your next steps for the Humpback whale research and other projects you're doing there in the Antarctic?

FRIEDLANDER: So, aside from this work that we're doing on the pregnancy rates, we have a concurrent project where we're studying the behavior of these animals, and it's really critical for us to study how these animals move, how they feed, how much time they spend doing different behaviors, where they do these things. And all of this will come together in a much greater understanding of why we see these outputs that we're seeing in the reproductive rates. We're flying drones over these animals to look at their body condition, so over time what we hope to be able to tell is – at what time during the feeding season are these animals putting on the most weight, and then where are they spatially when they're doing this. And that will tell us the critical areas and the critical times for these animals.

This figure from the study shows the proportion of pregnant and not pregnant female humpback whales sampled along the West Antarctic Peninsula. The mean pregnancy rate across all years was 63.5%. (Figure courtesy of Ari Friedlaender, UC Santa Cruz)

That will give us a leg up when we try to preserve areas and create marine protected areas to try and minimize the human impacts on these animals. And in the Antarctic peninsula, one of the growing concerns we have not only is climate change, but there's a burgeoning krill fishery that is working in the Antarctic peninsula and anything that we can do to proactively manage that fishery and try and have it work in a way that will not take out resources from the places and the times that are critical for not only whales but other krill predators, will make it, you know, much more likely that we can maintain these populations and continue to see them grow.

CURWOOD: So, how healthy is the population of humpback whales around the world in terms of being sustainable?

FRIEDLANDER: So, around the world there's almost a dozen discrete populations of humpback whales that are recognized, and almost all of them are increasing at a substantial rate. And many of these we think are at levels that they would have been preindustrial whaling era. We think of humpback whales as a really good success story for conservation and protection of the marine environment, and I think it's really important because in conservation, we need to celebrate the victories and we need to create hope and we need to have optimism that the things that we're doing are actually having an impact. There's not a lot of times where we can sit back and pat ourselves on the back and say, “hey, we did a good job,” but humpback whales around the world in different places give us that opportunity.

CURWOOD: And just how many humpback whales do we have on the planet at this point do you think?

FRIEDLANDER: I would think probably between 100,000 and 200,000 between those 12 different populations.

CURWOOD: That's a whale of a crowd.

FRIEDLANDER: [LAUGHS] Yeah, you wouldn't want to get mixed up in them at a concert.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Ari Friedlander is with the Institute of Marine Sciences at the University of California Santa Cruz. Thank you, Ari, for taking the time with us today.

FRIEDLANDER: Thank you, Steve. This was a real pleasure to talk to you guys, and I appreciate the opportunity.

Links

The study published in the journal Royal Society Open Science

The New York Times | “Humpback Whale Baby Boom Near Antarctica”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth