June 22, 2018

Air Date: June 22, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Seas Rising Faster With Antarctic Melt

View the page for this story

A new study in Nature finds Antarctica is now shedding more than 200 billion metric tons of ice every year, mostly from its western ice shelves. That’s three times the melt rate of just a decade ago, and climate disruption is largely to blame. Lead scientist Andrew Shepherd explains for Host Steve Curwood why the melting near the South Pole leads to more sea level rise, especially in the Northern Hemisphere, where the most people live on Earth. (09:10)

Boston’s Rising Tide

View the page for this story

Boston Harbor is subject to tides as large as 12 feet, and most of its original tidal flats were filled in the late 1800s. As sea level rises, storm surges combined with high tide are putting more and more of downtown Boston at risk of flooding. Journalist Courtney Humphries and Host Steve Curwood discuss. (04:15)

Humpback Whales Rebound

View the page for this story

Nineteenth century commercial whaling killed the vast majority of whales, but some species are coming back, especially humpbacks. Melting Antarctic ice has led to an abundance of krill, and with all that food humpback whales are thriving with high rates of pregnancy. University of California – Santa Cruz Researcher Ari Friedlaender tells Host Steve Curwood the comeback should be celebrated as a conservation victory, but there are questions about how long the krill boom might last. (13:00)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

On this week’s Beyond the Headlines, Host Steve Curwood and Peter Dykstra discuss the Chesapeake Bay’s improvement of ecosystem health and Costa Rica’s pledge to go fossil free by 2021. Finally, the pair step back into history and recall NASA scientist James Hansen’s testimony before then-US Senator Al Gore (D-TN) on the dangers of climate change, thirty years ago. (03:40)

The Last Lobster

View the page for this story

Maine lobstermen have hauled unprecedented catches and big profits in recent years. But now, the booming industry is seeing some signs of a downturn. Writer Christopher White interviewed dozens of lobstermen and lobsterwomen for his new book, The Last Lobster: Boom or Bust for Maine’s Greatest Fishery. He tells Host Steve Curwood what a warmer future might hold for the Maine lobster fishery as these crustaceans migrate north in search of colder ocean waters. (16:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Andrew Shepherd, Christopher White, Courtney Humphries, Ari Friedlaender

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood.

Scientists have focused for years on the melting ice from Greenland as a major driver of sea level rise, but new research points to the far south as well.

SHEPHERD: Unfortunately Antarctica is not isolated from the effects of climate change, and it's experiencing climate change. And so we should look to the projections for sea level that allow for that to happen. And they're not the ones that we're currently thinking about right now.

CURWOOD: Also, melting ice in Antarctica may put coastal cities at risk, but it’s good news for some whales.

FRIEDLANDER: We think of humpback whales as a really good success story for conservation and protection of the marine environment. We need to celebrate the victories. There's not a lot of times where we can sit back and pat ourselves on the back and say, ”hey, we did a good job;" but humpback whales give us that opportunity.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Seas Rising Faster With Antarctic Melt

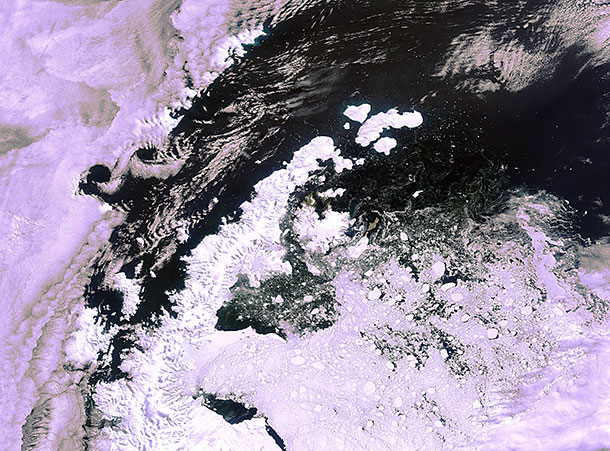

A new study in Nature finds 200 billion metric tons of ice are melting off Antarctica every year, a number that has tripled in the last decade. (Photo: NASA/GSFC/Jefferson Beck, Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Scientists have done a good job finding the links between human activity and climate disruption, but they tend to underestimate the actual rates of change. The latest unwelcome surprise comes from data that shows Antarctica is melting much faster than previously suggested, as much as 200 billion tons of ice loss each year. As a result, they say the rate of sea level rise has tripled over the past decade, with profound implications for coastal cities. Andrew Shepherd of the University of Leeds in the U.K. led a team of 80 researchers from around the world, including NASA, who gleaned the data from satellite and Earth observations. Welcome to Living on Earth!

SHEPHERD: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So, 200 billion tons. That's a pretty big ice cube. How much ice is that really?

SHEPHERD: So, you could visualize it as an ice cube if you like, and it would be about six kilometers either side, so a very large cube of ice. The practical way to visualize it is by spreading it out in the oceans because that's where it's going in the end, and today it's quite a small layer on top of the oceans – it's about 0.6 millimeters each year into the oceans.

CURWOOD: What percentage of the global sea level rise is that right now?

SHEPHERD: The recent assessment of sea level rise is for about 3.4 millimeters per year or about a fifth or a sixth of the total sea level rise. But in context, it used to be a much smaller proportion and the contribution is on the rise, and that's the thing that's of most concern.

The scientists used satellite data for their research, looking at factors such as changes Antarctica’s shape over time, as well as changes in the earth’s gravitational field. (Photo: ESA, Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: So, this is all very concerning. Tell me, I understand that sea level rise affects some areas more than others. Why is that?

SHEPHERD: It depends where the sea level rise comes from. So, if ice is lost in the southern hemisphere, that causes sea levels to rise more in the northern hemisphere because of the way the Earth's gravity balances it out, and vice versa. So, this particular story affects those of us that live in the northern hemisphere a little bit more.

CURWOOD: And how much ice is there in Antarctica? As I recall there's a couple of miles of it right at the South Pole.

SHEPHERD: Yes, I mean, most of Antarctica is pretty, I guess you would say, inert. It isn't changing very much. There's a very, very large ice sheet in Antarctica, so the easy way to conceptualize it is the amount of ice in Antarctica would amount to about 58 meters of global sea level change if it were to all melt. So that would be an extra 58 meters on to sea levels, and that hasn't happened for a very long time. But that's one way to visualize how much is there.

CURWOOD: You're saying that there's a round number of some 200 billion metric tons of ice that seems to be coming off of Antarctica every year. How did you get those numbers?

SHEPHERD: So, we have been able to use about a dozen different satellites that have been in space at some point or other since the early 1990s, and we have a few different techniques for measuring changes in Antarctica and also in Greenland. We can measure the change in the shape using satellite altimeters.

They’re instruments that can measure the height of Antarctica and how that changes over time. We have a bunch of different instruments that can tell us how fast the glaciers are flowing, some of them really sophisticated and some of them just taking photographs from space that we compare over time, see crevasses moving along. And then we have a new sensor – relatively new, it's been in orbit for ten or 15 years now – which measures Earth's gravity field. And changes, believe it or not, changes in the ice loading on planet Earth at the poles do affect the microgravity that the satellites sense in space. And so we can use those measurements as well to calculate how much ice is changing.

CURWOOD: Now, your study said that this rate of melting has tripled over the past decade. What information do you have about how that is happening?

SHEPHERD: So, when we look at Antarctica, we see that in east Antarctica, which holds most of the ice, there has been little change, so east Antarctica is by far the biggest part of Antarctica. It's where the South Pole is. That ice is actually sitting on an island that's above sea level, and we're pretty confident that the reason it hasn't experienced any change is because it's isolated in the main from the oceans and we think that the oceans are the way the Earth's heat is being delivered to Antarctica. The atmosphere in Antarctica is very cold. It seems obvious, but it is cold.

Most of the ice in Antarctica is on land, but on its western side where glaciers flow into the ocean there are large floating ice sheets. As global temperatures rise due to climate change, the West Antarctic ice sheets encounter warmer waters that promote melting. (Photo: Ronald Woan, Flickr)

Never really gets above freezing except in some very, very isolated places. With an average temperature about minus 40 degrees Centigrade you would need to heat the planet a lot to change the ice via the air. But the ocean surrounds west Antarctica, and the ocean is already above freezing -- that's why it's wet -- and so you can deliver heat quite effectively through the oceans if you change their temperature. And we think that all the ice loss, well, we know all the ice loss is happening in west Antarctica, and we think it's due to the ocean being too warm there.

CURWOOD: Please compare for me Antarctica’s ice loss to the rapid melting we've seen from Greenland.

SHEPHERD: It has been very clear that Greenland has lost more ice each year over the past 20 or 30 years, and that is largely because Greenland is farther from the North Pole than Antarctica is from the South Pole and sits in a relatively warmer climate. So, if you visit Greenland in summer, it's above zero temperature and at times it gets up to quite warm temperatures. 20 degrees Celsius is not uncommon. And so Greenland loses a lot of its ice through melting, not just through glaciers calving icebergs into the sea. And so, this argument about small changes in Earth's planetary temperature and how they affect an ice sheet is different for Greenland. If you raise the planet's temperature by one degree Centigrade, in summer you melt more ice from Greenland, and that's what's been happening over the past 20 or so year. In Antarctica, it was a very different story. We didn't think that the ice was melting from the surface – it still isn’t. But we also weren't sure whether heat could be delivered to Antarctica via the oceans either. And that's because Antarctica is situated south of a part of the planet where there is an uninterrupted ocean. So, if you look between Antarctica and the southern tip of South America, there's a band of ocean there which has a very, very active current traveling around it, and people used to think that that ocean was impervious and wouldn't allow heat changes elsewhere on the planet to be transmitted across it. That doesn't seem to be the case anymore.

CURWOOD: Andrew, how did you feel when you got these findings?

SHEPHERD: I think we were definitely – and it's not just me, as we have a team of 80 or more people involved and many more involved in the space agencies – we were all very surprised. We didn't expect Antarctica to jump up there in terms of its ice losses and start to rival Greenland, but that's happened. And part of the reason that we're reporting Antarctica now is because it's an important piece of information, such a high profile piece of information, we think that people need to be aware about it.

As sea levels rise, the frequency of floods is expected to increase and the Antarctic melting means the Northern Hemisphere will be more affected by these changes. (Photo: Joe Shlabotnik, Flickr)

CURWOOD: So, what's the takeaway from all of this research, Andrew?

SHEPHERD: So, the takeaway message is that unfortunately Antarctica is not isolated from the effects of climate change, and it's experiencing climate change, and so we should look to the projections for sea level that allow for that to happen, and they're not the ones that we're currently thinking about right now. We definitely did underestimate what would happen in the present five years when we looked at this problem five years ago. So, we need to be thinking about an extra 20 or so centimeters of sea level rise in the northern hemisphere if the continent of Antarctica continues to follow the trajectory that it is actually on now. And that will be a number of significance to urban planners. It may not sound a lot to people at home, but it will affect the frequency with which coastal areas flood today.

CURWOOD: What keeps you going despite all these daunting findings? This is a threat to civilization itself.

SHEPHERD: Ah, well – doing nothing is the threat and knowing nothing is the threat. Knowing something is definitely not a threat. Knowing something is being prepared for action, and I've been very pleased about the impact that this work has had. People are interested to learn about it and I hope that that means that people have listened and heard the message, and the politicians who are ultimately responsible for changing the course of our futures will act on that. So, I don't see it as a bad news story. I think it's really good news that we're able to tell people that they need to be concerned. Because we can act.

CURWOOD: Andrew Shepherd is a Professor of Earth Observation at the University of Leeds in the U.K. and directs the Center for Polar Observation and Modeling. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SHEPHERD: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- The Antarctic Ice Melt Study

- The Washington Post | Antarctic Ice Loss Has Tripled

- The History of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet

- Science of Ocean Temperatures and Ice Melt

[MUSIC: Maria Kalaniemi, “Olin Sairas Kun Luokseni Saavuit (I Was Sick When You Came To Visit Me),” on Maria Kalaniemi, Traditional Finnish/M. Kalaniemi/arr.M. Kalaniemi & T. Alakotila), Xenophile/Green Linnet Records]

CURWOOD: Just ahead – over time, sea levels only rise inch by inch. But when a big storm coincides with high tide, the surge can make for plenty of trouble, especially in a city that has king tides of twelve feet. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth – stay with us!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at race to nine billion dot com. That’s race to nine billion dot com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[MUSIC: Maria Kalaniemi, “Olin Sairas Kun Luokseni Saavuit (I Was Sick When You Came To Visit Me),” on Maria Kalaniemi, Traditional Finnish/M. Kalaniemi/arr.M. Kalaniemi & T. Alakotila), Xenophile/Green Linnet Records]

Boston’s Rising Tide

The Boston Seaport. (Photo: Leslee_atFlickr, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Sea levels are rising everywhere, and the advance is a steady creep. But storm surges can provide early signs of looming inundation with tides rolling the dice of just when and where. The City of Boston is built mostly on land that once was tidal flats. It got a wakeup call earlier this year when the first of a string of Nor’easter storms hit just as the tide was peaking. The ocean spilled into the subway and homes up and down the nearby coast. The Union of Concerned Scientists projects by the end of the century, Boston will see close to seven feet of sea level rise, putting 89,000 Massachusetts coastal homes worth $63 billion at risk from tidal floods. Courtney Humphries is a writer and graduate student at UMass Boston. She gave us a tour of Boston’s waterfront.

HUMPHRIES: Boston has this great tidal range of over 10 feet. In the US, most tidal ranges are more three to five feet, that kind of thing. So, Boston is kind of unusual for U.S. cities that way.

CURWOOD: So, let's go back in history. What was Boston's relationship with the tides back in the day?

A map of Boston Harbor in 1775. Boston was a peninsula attached by a thin sliver to the mainland, where today’s Washington Street runs. Land for neighborhoods like Back Bay and Seaport were still underwater. (Photo: Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons)

HUMPHRIES: One of the nice things about having these tides come in and out is that it did actually flush out the harbor. It was a great way for the city to get rid of its waste back in the day when we just put everything into the water. For a long time like many cities in the 19th century, it struggled with all the sewage that was being just dumped into the waterways, and I would say at low tide Boston was notorious for smelling very badly. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: Let's fast forward to 2018 when people became well aware of Boston's tidal situation. Talk to me about that.

HUMPHRIES: Well, I think you know in recent years we have become more aware of tides, partly because of king tides. When we have these king tides, which are especially large, maybe a couple times a year, people have noticed that the water actually will pour over into some areas of Boston on the waterfront. But then, you know, this winter we had these Nor'easters and when they coincide with high tide, it was flooding that we haven't seen before. But, you know, the sea levels are rising. A lot of the things that wouldn't have come on to dry land in Boston are coming on to dry land now and they're creating floods.

CURWOOD: One thing about tide, Courtney, is that it comes with quite a bit of power. This isn't a sort of gentle stream, but it really slams into the shore. How did that affect what happened during the Nor'easters?

HUMPHRIES: So, it's sort of a combination of what's called the storm surge from the storms and that's all the wind building up really creates this wall of water, and when that coincides with high tide, it just creates this huge flooding potential. And so, we've actually been very lucky with our tidal range in some ways because when a storm hits, a really bad storm hits at low tide, that's a 10 feet difference, so we don't actually get as bad of a storm as we might. So, the tidal range, I think, is going to become much more important as we deal with storms in the future.

CURWOOD: So, what happened in Boston during Superstorm Sandy with the tide here?

Pilot boats docked at the Boston Rowing Center in Fort Point Channel. Color changes on the horizontal pilings show the difference between high and low tide. (Photo: Hannah Loss)

HUMPHRIES: Well, we were lucky. We were luckier than New York. Superstorm Sandy hit at a lower tide, so if it had hit at high tide, it would have really damaged the city a lot more, and I think that that awareness that the tide sort of saved us in that sense, has led to a lot of the planning that we have now around climate change resilience in Boston.

CURWOOD: So, Boston will celebrate its 400th anniversary in just a little while. What will this area be like in 400 years with what we know about rising seas and climate disruption?

HUMPHRIES: Well, it will be under water, I think, unless we can stop – really, really quickly stop greenhouse gas emissions, sea levels will continue to rise. I do think we can protect a lot of parts of Boston. Maybe we'll be going through another era of reshaping the city physically the way that they did back in the 19th century, but for different reasons.

CURWOOD: Courtney Humphries is a journalist and a PhD student in environmental science at UMass Boston. Courtney, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

HUMPHRIES: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Courtney Humphries’ article in The Boston Globe | “Boston Vs. the Rising Tides”

- The Boston Globe | “Scenes from the powerful Nor-easter”

- Explore the city’s maps, projects, and plans

- National Geographic: “How Boston Made Itself Bigger”

[MUSIC: Miles David & Quincy Jones, “Orgone” on Live at Montreux, by Gil Evans, Warner Bros. Records]

Humpback Whales Rebound

Ari Friedlaender deploying a motion-sensing and video recording tag on a humpback whale in Andvord Bay, Antarctic Peninsula. Collected under NMFS and ACA permits. (Photo courtesy of Ari Friedlaender)

CURWOOD: While the ice melting in Antarctica poses a threat to coastal cities, there is at least one species that so far is benefiting. The population of humpback whales is flourishing these days, with a baby boom, or should I say, calf boom. It’s all related to the shrinking of the floating ice shelves off Antarctica, as Ari Friedlaender at UC Santa Cruz has found. He joins us now – welcome to Living on Earth, Ari!

FRIEDLANDER: Thanks a lot. Thanks for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, you're telling me there's some good news for whales. What exactly did your team find out about the humpback whale populations?

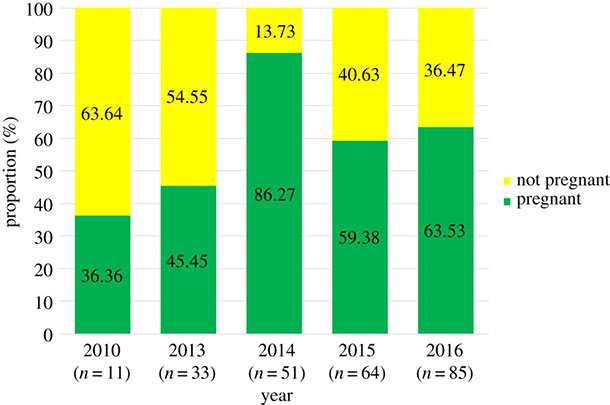

FRIEDLANDER: This was a project that we did in the Antarctic on the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula, that area that is below South America, and over a five- or six-year period what we did was to collect small skin samples from as many humpback whales as we could, and we used those samples to determine how many females in the population were pregnant each year. And what that is a good indicator of is population growth. And so what we found was that there were really high levels of pregnant females in the population in every year of our study, and that to us is a good indicator that this population is growing.

CURWOOD: So, what's a high level of pregnancy?

FRIEDLANDER: Oh, I think on average we had over 50 percent of the females in the population were pregnant in any given year, and I think in one year we had over 70 percent of the animals pregnant as well.

UAS image of two adult humpback whales in Andvord Bay, Antarctic Peninsula. The whale at the bottom is carrying a motion-sensing tag. Collected under NMFS and ACA permits. (Photo: Duke Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing Lab)

CURWOOD: And generally how often do humpback whales get... should I say, knocked up?

FRIEDLANDER: [LAUGHS] You can, yep, um… [LAUGHS] In other populations around the world, typically two or three years is the interval between having a calf, and it takes the animal that long just to be able to grow a calf and then wean it. In the Antarctic, one of the things that we found was that we had some humpback whales that were reproducing annually. So, these would be humpback whales, 40-45 feet long, weigh about 40 tons, lactating, and growing a calf inside them at the same time, which is an extremely energetically costly thing to do, and something you really can only do if you have almost an unlimited resource in terms of the availability of food.

CURWOOD: So, what is the significance then of these increased pregnancies and therefore the increased humpback population?

FRIEDLANDER: You know, the significance is that about a hundred years ago, humans in the commercial whaling industry in the southern ocean killed over two million baleen whales. And these are staggering numbers. There is a void of baleen whales in the southern ocean at this point, and since the cessation of commercial whaling in the 1980s, where effectively we're now leaving those animals alone – what this shows is that if you do leave some of these populations alone they do have the capacity and the ability to rebound. And we should be hopeful and optimistic at some level that we can reverse some of the things that we did that were so detrimental to these animals.

CURWOOD: Remind folks which whale species are baleen whales.

FRIEDLANDER: So, the baleen whales are the largest of the whales – the blue whale, the fin whale, humpback whale. These are called baleen whales because of the way that they feed. Instead of having teeth, they have these bristles or these sheets of baleen in their mouth which is made up of keratin – same thing that our fingernails are made of – and so what they do is they take in a huge volume of water that's got a lot of very small either crustaceans or small fish in it, and then they use a really massive tongue to push that water out of their mouth. And the baleen acts like a sieve and it keeps all the small food items inside.

CURWOOD: So, you know this information from samples of humpback whale skin. How do you get some humpback whale skin?

FRIEDLANDER: [LAUGHS] Yeah, it's um…. It’s an interesting process, and it's actually pretty fun. We have crossbows that we use and we have a very specialized tip on the end of that crossbow that's about the size of a pen cap and it's hollow in the middle, and we shoot a small dart at the whale. We hit it on the back up near the dorsal fin. The tip of the dart goes in about an inch, maybe an inch and a half, and pulls out a really small sample of skin and blubber, and then that that sample floats at the surface. And the bolts – we collect it, we put it into a vial, and then we freeze that until we get back to our laboratories. And then we do a pregnancy test that's based on the hormone progesterone, which is the same hormone that we have as humans that's a good indicator of pregnancy.

CURWOOD: If somebody shot a bolt into my back and took out an inch of flesh, I'd be saying, “ouch!”, maybe even louder than that. How do the other whales feel about this?

FRIEDLANDER: It's interesting. We see a variety of responses, but none of them are ever more than just a very transient... you know, it might act like it wasn't expecting to get touched or it might be like when you get bit by a mosquito. It's a very small thing relative to the size of the animal, and in fact, the animals tend to react more if we miss them, and the sound of the bolt hitting the water startles them even more so than when we take a sample.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about what it's like to conduct research in the Antarctic.

FRIEDLANDER: It's a unique place. One of the biggest challenges I have is to describe the Antarctic to people. It's an incredibly foreign and hostile place. I mean, if we aren't on a big research boat, we're not going to survive down there. So, it's incredibly hostile, but it is also the most magnificent and beautiful and just pristine area. Seeing the animals that live down there, the penguins and the whales, all of the seals and the enormity of the glaciers and the cold of the ocean and the ice around you, it gives you this sense that there are parts of this planet that are wild and that are just not suitable for people to be, and so you feel very small. It’s very humbling. But it's an incredible place, and I feel incredibly fortunate to be able to work there.

UAS image of a mother and calf pair in Andvord Bay, Antarctic Peninsula. Collected under NMFS and ACA permits. (Photo: Duke Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing Lab)

CURWOOD: Talk to me about why you think there were so many pregnant females, and, even more than that, ones nursing at the same time they were pregnant. What do you think is the cause of this whale baby boom?

FRIEDLANDER: You know, I think the cause of this – what we're calling this whale baby boom is – it's got a couple of different reasons, some good and some maybe not so good. The good is that these animals are simply reproducing very quickly because when we took out all of those whales in the last hundred years, there was this void of krill predators and so these whales are responding to the availability of food that was left over by all the whales that weren't there, and they're showing, or we're showing, that these animals have the capacity to rebound and come back to these places. The bad thing, unfortunately, is that the Antarctic peninsula is warming faster than almost any other place on the planet, and the way that that is manifesting is that there are less and less days that are covered by sea ice. So, in a given year you might have winter that comes a month later, and spring that comes a month earlier. So, for an animal that feeds on krill – and these whales don't go into the sea ice – that might mean that you have about two months greater time that you can be down in the Antarctic feeding, and that's exactly a way to translate food into energy, which means you can reproduce quicker. So, it may be that climate change is actually increasing the number of days for these whales to be able to forage and therefore to gain energy and reproduce.

CURWOOD: But?

FRIEDLANDER: That may not be a good thing for the ecosystem that's evolved down there to live on ice. The krill that these animals feed on are evolved so that they feed on the undersea ice community in their first year, and so without sea ice the first year’s worth of krill each year may not survive, or it may be a much diminished amount of krill that's available the next year. That then has consequences because eventually those krill will be the cohort that reproduces, and if there's not a lot of them to reproduce, it's a very quick step down in terms of how much food is available for all the krill predators, and then you limit how many animals might actually be able to subsist on that krill. So, while right now it might be a very good time to be a humpback whale, in the future, once the changes that are happening affect the amount of food that's available for them, it's going to limit how many animals can be there.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think we're looking at a whale bubble?

FRIEDLANDER: That may be a really good way to put it. I think for things like minke whales, which are the small endemic species that lives in the sea ice, they're going to have to find a different place to live and they're going to be forced out. There's going to be a lot of humpback whales, hopefully things like blue whales and fin whales will also increase, but there is going to be a carrying capacity that gets met. The other thing is that in nature when resources become limiting, you have competition, and it may be that humpback whales are going to compete with the penguins or the seals or the other things in the Antarctic that rely on krill as a main food source. And nature has a way of sorting those things out, and it typically means there's going to be winners and losers.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about the other whale species aside from the humpback that at this point benefit from less sea ice.

FRIEDLANDER: Right now in the Antarctic, the humpback whales are really the only ones we can measure this in, because fin whales and blue whales have not responded in an appreciable way to the cessation of whaling. One of the things that makes humpback whales so capable of reproducing quickly is because they have a very centralized breeding ground. There's a lot of places up and down the coasts of the U.S. and Australia and South Africa and South America where people know humpback whales go to breed. So, it's a lot easier to find a mate if everybody goes to the same place. For fin whales and blue whales, we don't think that there are these centralized breeding grounds where all the animals go and aggregate, so if your population levels get depressed like they have been, finding a mate can be a very hard thing.

CURWOOD: So, I take it whales don't have social media.

FRIEDLANDER: They don't have social media, absolutely not, but they can communicate across really big distances because of how loud and low frequency some of their calls are, but even with that it can be hard to find another mate in a pretty big ocean.

CURWOOD: Hey, Ari, tell me – what are your next steps for the Humpback whale research and other projects you're doing there in the Antarctic?

FRIEDLANDER: So, aside from this work that we're doing on the pregnancy rates, we have a concurrent project where we're studying the behavior of these animals, and it's really critical for us to study how these animals move, how they feed, how much time they spend doing different behaviors, where they do these things. And all of this will come together in a much greater understanding of why we see these outputs that we're seeing in the reproductive rates. We're flying drones over these animals to look at their body condition, so over time what we hope to be able to tell is – at what time during the feeding season are these animals putting on the most weight, and then where are they spatially when they're doing this. And that will tell us the critical areas and the critical times for these animals.

This figure from the study shows the proportion of pregnant and not pregnant female humpback whales sampled along the West Antarctic Peninsula. The mean pregnancy rate across all years was 63.5%. (Figure courtesy of Ari Friedlaender, UC Santa Cruz)

That will give us a leg up when we try to preserve areas and create marine protected areas to try and minimize the human impacts on these animals. And in the Antarctic peninsula, one of the growing concerns we have not only is climate change, but there's a burgeoning krill fishery that is working in the Antarctic peninsula and anything that we can do to proactively manage that fishery and try and have it work in a way that will not take out resources from the places and the times that are critical for not only whales but other krill predators, will make it, you know, much more likely that we can maintain these populations and continue to see them grow.

CURWOOD: So, how healthy is the population of humpback whales around the world in terms of being sustainable?

FRIEDLANDER: So, around the world there's almost a dozen discrete populations of humpback whales that are recognized, and almost all of them are increasing at a substantial rate. And many of these we think are at levels that they would have been preindustrial whaling era. We think of humpback whales as a really good success story for conservation and protection of the marine environment, and I think it's really important because in conservation, we need to celebrate the victories and we need to create hope and we need to have optimism that the things that we're doing are actually having an impact. There's not a lot of times where we can sit back and pat ourselves on the back and say, “hey, we did a good job,” but humpback whales around the world in different places give us that opportunity.

CURWOOD: And just how many humpback whales do we have on the planet at this point do you think?

FRIEDLANDER: I would think probably between 100,000 and 200,000 between those 12 different populations.

CURWOOD: That's a whale of a crowd.

FRIEDLANDER: [LAUGHS] Yeah, you wouldn't want to get mixed up in them at a concert.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Ari Friedlander is with the Institute of Marine Sciences at the University of California Santa Cruz. Thank you, Ari, for taking the time with us today.

FRIEDLANDER: Thank you, Steve. This was a real pleasure to talk to you guys, and I appreciate the opportunity.

Related links:

- The study published in the journal Royal Society Open Science

- The New York Times | “Humpback Whale Baby Boom Near Antarctica”

- Humpback Whale Sounds

[MUSIC: Songs of the Humpback Whale, Roger Payne]

CURWOOD: These humpback whales songs were recorded by Roger Payne.

Beyond The Headlines

The Central American nation of Costa Rica will be fossil fuel free by 2021, according to its new President, Carlos Alvarado. The nation’s cloud forests spur a culture of sustainable travel and ecotourism. (Photo: Dirk van de Made, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Let’s take a moment now to look behind the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter’s an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. On the line now in Georgia – Peter, what’s going on down there? It’s plenty hot here outside of Boston.

DYKSTRA: Plenty hot here today as well, Steve, hi. I’m going to give you some good news, and then I’m going to give you some more good news. Are you ready for that?

CURWOOD: Uh, okay, I’m sitting down. Wow.

DYKSTRA: There’s an annual report that measures the state of Chesapeake Bay. It’s been bad news after bad news after bad news for 33 years. But the bay grass at the bottom of the bay, one of the keys to its ecosystem, is improving, and the whole bay has had its best report in 33 years.

CURWOOD: Wow, that’s great. So, how did they do this? What fixed the Chesapeake Bay, or got it better, anyway?

DYKSTRA: Well, the Chesapeake is dealing with pressures from urban growth. The population around the bay in places like Washington and Baltimore and Richmond and Norfolk Virginia has doubled since 1950. There’s also huge farm runoff from dairy farms in New York state and Pennsylvania, poultry farms in Maryland and Virginia. They’ve all really beaten up the bay. Seafood, like oysters and crabs, are declining. But a massive federal cleanup program is really hitting the mark and is making a big difference.

CURWOOD: Okay, you said you had two items of good news. What’s the other one?

The Chesapeake Bay Watershed area is known for its oyster and crab industries and its estuary systems. Pictured here is a tidal wetland area in the Bay. (Photo: Jennifer Schmidt)

DYKSTRA: Yeah, here’s a little more. There’s a new president in Costa Rica, elected in May. His name is Carlos Alvarado, and President Alvarado has set a really lofty goal for his environmentally-conscious country. He calls it “a titanic and beautiful task,” and they want to have fossil-fuel-free Costa Rica by the year 2021, which would also be the nation’s bicentennial.

CURWOOD: Woah, that’s ambitious. How are they going to do that?

DYKSTRA: Critics say they aren’t going to do it, or at least they’re not going to do it in less than three years. But, they’ve got a head start on environmental programs and everything from ecotourism to clean energy. If any country can do it, Costa Rica may be the one.

CURWOOD: Indeed, they’ve been certainly iconic in that ecotourism, haven’t they? Okay. Now we’re going to take that walk down the halls of history and you’re going to tell me about…?

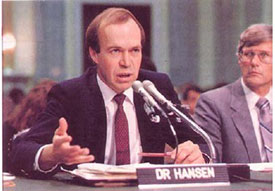

DYKSTRA: I’m taking you back thirty years to June 23rd, 1988 to Jim (James) Hansen, the climate scientist, and his historic testimony before a senate subcommittee. It was a scorching hot day in Washington, and Hansen’s predictions about climate change, ones he had made before, but they really hit home and made news.

/>

/>Former NASA scientist and Columbia University Professor James Hansen testified before Congress on June 23, 1988. Hansen was recently quoted saying that he wishes he wasn’t wrong about climate change. (Photo: NASA)

CURWOOD: That hearing, as I recall, was chaired by a young senator from Tennessee named Al Gore.

DYKSTRA: Right. Hansen and Gore had been in a neck and neck race for thirty years to see who could be the most criticized and reviled for being right.

CURWOOD: And what does Jim Hansen think about that scene from 30 years ago?

DYKSTRA: He’s really sorry that he turned out to be right. He’d much preferred to be wrong. I would have to agree with that. I have been following these issues for a long time. The science is compelling. But I would be more than happy to have all of the scientists and all of the journalists who have written and talked about this for years get some egg on their face and be completely wrong. Let me give you one more bit of pop culture trivia about Jim Hansen’s office at Columbia University. It’s upstairs from the iconic diner that was featured in episode after episode of the Seinfeld show.

CURWOOD: So, hm, no soup for you?

DYKSTRA: No, that’s a different restaurant. So, no soup for you!

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Talk to you again real soon Peter.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more about these stories at our website loe dot org.

Related links:

- San Antonio Express News | Chesapeake Isn’t Healthy

- Independent | Costa Rica Bans Fossil Fuels

- More on James Hansen’s Testimony

[MUSIC: Bari S., “Seinfeld Theme Original,” YouTube cover: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ONWp6jfykI0]

CURWOOD: Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line anytime at 617-287-4121. That's 617-287-4121. Our e-mail address is comments @ loe dot org – comments @ loe dot org. And visit our web page at loe dot org. That's loe dot org.

Coming up – how climate disruption is chasing Maine’s iconic lobster north. That’s just around the corner here on Living on Earth – Keep Listening!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[MUSIC: Paul Winter, “Lullaby From the Great Mother Whale To the Baby Seal Pups,” on Callings, by Paul Winter and Paul Halley, Living Music]

The Last Lobster

Lobster boats at dusk in Stonington, Maine – the onshore geographic center-point of Maine’s lobster fishery. (Photo: Whewes, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. For more than a decade, the State of Maine once featured a red lobster on its license plates to honor its iconic fishery. But today the lobster is gone from those license plates, replaced by the state bird – the chickadee. And lobster may not even dominate Maine’s fisheries forever. It turns out that as U.S. east coast waters have warmed as part of climate disruption, the epicenter of lobstering has shifted north from Casco Bay near Portland to Penobscot Bay, a distance of 160 miles or so. Christopher White has written a new book, “The Last Lobster: Boom or Bust for Maine’s Greatest Fishery,” and he joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

WHITE: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, for the record, first, Chris, do you eat lobster?

WHITE: I love lobster. I'm a big fan of lobster.

CURWOOD: Ah! With butter or...?

WHITE: Well, I'll tell you, I used to eat it with butter before I started this book project, but spending three or four summers and winters in Maine like I did, I learned to eat lobster the way the local lobstermen eat it, which is with vinegar.

CURWOOD: Indeed. [LAUGHS] Now, in recent years there was a glut of lobsters along the Maine coast. Why, and how has that boom impacted prices?

The Last Lobster book cover. (Photo: Courtesy of Staci Burt)

WHITE: OK. You know, I knew that there was a glut going on with Maine lobsters. In 2012, for the first time, lobsters went over 120 million pounds a year. And that is approximately six times what the lobster catch was in the 1980s when it was just about 20 million or 25 million pounds for the catch. And that level of harvest continued for five more years, 2012 through 2016 it continued. It was a real boom and immediately in 2012, when it first happened, the price plummeted because there was an oversupply of lobsters and the wholesalers couldn't move the lobsters – there were just too many. So, the price plummeted from about $4 a pound down below $2 a pound, which just killed the lobstermen. What the lobstermen did in response was they tried to fix the supply chain, but also what they did was they started to fish much harder. The lobstermen tried to make up in volume what they lacked in price by catching more and more lobsters. They also started to make more money doing that and they became overconfident, really, with how much they were making. Some lobstermen for the first time ever were making $200,000 a year. Teenagers, high school teenagers, were making $50,000 or $60,000 in the summer. And so that was just incredible, and that led to – when they had all this money in their pocket, the local lobstermen started to spend wildly, they bought bigger boats, they hired more crew, and they got way overextended.

CURWOOD: So, how did the individuals that you followed handle this glut? Let's talk about Frank, for example.

WHITE: Yeah, Frank Gotwals is a great character. He is 62 years old and has been lobstering since he was 20. He dropped out of college to move back to his grandparent's home up in Stonington, Maine, so that he could lobster. He worked harder. He went out every day, six or seven days a week, and worked as hard as he could to make up for that lack of price that we were just talking about, and he did very, very well.

Lobster Captain Frank Gotwals shows off his catch. (Photo: Donna K. Grosvenor)

The other thing that Frank did unusually was that, he took it upon himself to try to increase the demand of lobsters, so that their price would go back up. And he and some other people created a thing called the Maine Lobster Marketing Collaborative, which strives to increase the price and demand of lobsters domestically and overseas. And they just tried to build a bigger demand, which they've done, and the price started to climb up over the last couple of years.

CURWOOD: Indeed right now the prices back up in the double digits, isn't it?

WHITE: It is, it is. And I really look at that as a response of the lobstermen to global warming. They had a glut and a price decrease because of global warming, and they responded to that by trying to increase the demand for lobsters – and they got a better price, so they succeeded.

CURWOOD: So, let's talk about global warming. This is an important part of your book. How does global warming figure into this kind of boom and bust cycle in lobstering?

WHITE: Scientists and fishermen thought that there were probably three main culprits that could be causing the boom. The first was a lack of predators. Cod and other ground fish that had been wiped out from overfishing over the last 20 years were voracious predators of baby lobsters. The second theory was that kelp had increased in its proliferation on the Gulf of Maine because sea urchins were overharvested and sea urchins eat kelp, and that gave protection and camouflage to baby lobsters. But the third reason is global warming, and the reason why people suspected this was that with the temperatures that were increasing so much, not just on land but also just the water temperatures in the Gulf of Maine, meant that lobsters were molting earlier. They were molting in June rather than July. They were doing repeat molting where they were molting more than once in the summer, maybe twice, maybe again in the autumn – unheard of really. And the third thing that was happening was that the lobsters were going through early maturation, where females that used to become only able to breed once they were of legal size, they were now breeding at six to seven years in their life cycle. The irony is that the same factor that was causing the boom could be leading to a bust.

Lobsterman Jason MacDonald – one of three boat captains whom Chris White followed over the course of several lobster seasons. (Photo: Donna K. Grosvenor)

CURWOOD: And how's that?

WHITE: OK. The best way to look at this is to look at Long Island Sound as sort of like a preliminary story. In Long Island Sound in the 1990s, they were having a boom because of temperatures and the lobsters were breeding very well. But then in 1999, the lobsters took a nosedive in the Long Island Sound and started to disappear. And then later in 2013, the state of Connecticut reported that over 11 million lobsters died in one summer – nearly 90 percent of the population died from the heat, really like a heat stroke, essentially. So, global warming at modest increases in temperature were causing a population increase, but at higher temperatures they were causing death and a population decrease. So, it's really like two sides of the same coin.

CURWOOD: So, a little bit warmer is a little mo’ bettah for lobsters, a lot warmer is bad news.

WHITE: Exactly true.

CURWOOD: Where are we now on that cycle, do you think, Chris?

WHITE: It's hard to know. It's hard to make predictions, too. In 2017, after the five years that we had from 2012 to 2016 where all the catches in Maine were over 120 million pounds – in 2017, it dropped 16.4 percent. It dropped from 132 million down to 110 million, and that's a very significant drop. If we have a similar drop this summer in 2018, it's really going to spell trouble, but who knows what will happen. It could increase again, it could stabilize, or it could continue to fall.

CURWOOD: You know, I spent some time out in the Hamptons on Long Island back in the late 90s, and I do remember when there was this sort of amazing glut of lobster. It was available at restaurants at very reasonable prices to take home, and then suddenly it was gone. This could be the experience in Maine, it sounds like.

WHITE: It could happen. It could be another story, I mean, it's sort of happened all the way up the coast. It's like a domino effect happening because first Connecticut and Rhode Island and New York State had trouble with the Long Island Sound, and then Narragansett Bay, and then in Massachusetts, Buzzards Bay started to lose their lobsters – and the same harvest decreases have happened up the coast. Some people say, “oh, well Maine's too cold, Maine's cool enough that it's not going to happen there,” but it's been happening all the way up the coast like dominoes.

CURWOOD: The lobstering business has never been particularly easy and given the volatility of the supply and the economy, why do so many folks – and many folks actually risk their lives – to go out and haul their pots to bring us lobsters?

Lobster stands like these are a common sight along the Maine coast. Red’s Eats in Wiscasset is a famous and popular seafood joint. (Photo: Wally Gobetz, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

WHITE: Well, I think the first reason is the love of the life. Lobstermen, like commercial fishermen all around the world, around this country, they love their life and they love their livelihood, and it is beautiful to be out there on a lobster boat at dawn when the sun comes up. So, that is a real attraction for most of them, I think. Then secondly, most of the lobstermen up in Maine are sons and grandsons and granddaughters of former lobstermen. And so it's something that they did when they were little children. They were taken out on a lobster boat by their grandfather when they were four or five years old, and they became enchanted with it, I think. But then third I would say is that there's just a lot of money to be made. I mean, they're making a lot of money. The lobstermen that go far out into the ocean sometimes make over $500,000 in a year.

CURWOOD: So, regarding the state of the lobster fishery and really regarding the longevity of their way of life, talk to me about the attitudes of the more seasoned lobster folks as opposed from the younger captain.

WHITE: Julie Eaton, my female lobster captain that I went out with and wrote a chapter on, she said at one point in the day that – and I'm going to paraphrase her a little bit here – she said, we're not really certain about global warming but we're keeping an eye on it. But if it is true, we're really in trouble. And then she said, what lobstermen worry about, they don't talk about it, but what they worry about is going out one morning in their boat and picking up their traps and finding them empty. And so I think that the older lobstermen that are 50, 60, 70 years old, they're talking about trying to lobster through the end of their lifetime or until retirement, but they're worried what's going to happen to their children and grandchildren, whether there are going to be enough lobster to fish.

Lobster Captain Julie Eaton with her partner Sid. (Photo: Donna K. Grosvenor)

CURWOOD: So, you mentioned that one of the lobster people, Julie Eaton, says, well, maybe there's climate change, maybe there isn't. How do the other lobster captains feel on this question of global warming?

WHITE: Well, some of them believe it's true and valid and affecting the lobster population and others deny it. It's like the population of the United States. There are some people that are climate deniers and some people embrace it. And lobstermen are very similar to that. They know that fisheries have been cycling for decades and fisheries go up and down and the lobster fishery is no different from that. And so they say, well, it's probably just another dip, but they just, they want to believe that it's just another dip. They don't want to believe that it's a bigger problem than that, but the evidence is starting to come forward that it is a more serious consideration, and that global warming and ocean warming specifically are behind the problem.

CURWOOD: Lobstering is so closely identified with Maine that they put it on some of their license plates. It's really part of the cultural identity. How do you think it's doing with this cultural icon being in the crosshairs?

WHITE: Well, the whole identity of the coast of Maine is wrapped up in the lobster, isn't it? I mean, not just economically and also as far as livelihoods go, but also in terms of tourist dollars. I mean, people come to Maine for the summer in large part to eat lobster. It's a part of this experience. If you go to Boothbay Harbor or Camden or Bar Harbor for a summer visit, the one thing that you want to do while you're there is eat some lobster, so it's very important and part of the whole identity of the place.

The Last Lobster Author Christopher White. (Photo: Donna K. Grosvenor)

CURWOOD: So, if lobsters are so iconic to Maine, and the trajectory of them would seem to be down, what are people saying in terms of limiting both the catch and the export of lobsters?

WHITE: I asked this question. It's a great question and I asked it of most lobstermen that I talked to – why can't we decrease the catch? And that would boost up the price and make the fishery even more sustainable than it might be already, and it makes so much sense to do that. And there's some fisherman like Frank Gotwals that want to do that, but no one else will do it. There have been many debates going on among lobstermen to decrease the number of traps they have in the water, but they won't cut back. They will not cut back.

CURWOOD: Now, what do you make of folks that say that we're looking at signs that the lobster boom may be coming to an end. This year the catch is down after setting that record a couple of years ago. What does this say about the future of Maine's lobster fishery?

WHITE: Well, some people are saying that the only way out of this to make sure that lobstermen don't have to leave the coast of Maine and go to Bangor and Portland to get jobs, or the gentrification starts to happen more than it already has – is to diversify. Because right now, lobstermen and fishermen in Maine are overly dependent upon the lobster. Eighty percent or more of the total catch in dollar value in Maine, the State of Maine, comes from lobsters. So, that sort of dependency makes lobstermen and fisherman very vulnerable to any downturn like we're talking about. So, how can they diversify? They can turn toward sea farming and raise oysters, scallops, mussels, clams and other mollusks that are good for sea farming, and there are a number of fishermen that are already doing this. There's one of the lobstermen that I interview in the book, Peter Miller, who lives at Tenant’s Harbor, has just joined with some other lobstermen to start a scallop farm. So, they're looking to diversify as a way out.

CURWOOD: Christopher White's book is called “The Last Lobster: Boom or Bust for Maine's Greatest Fishery.” Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

WHITE: I enjoyed it, Steve.

Related links:

- The Last Lobster Book

- Bangor Daily News | Lobster Boom Won’t Last

[MUSIC: Tomoko Sugawara, “Ebb Tide” on Oasis: Classical & Instrumental, Volume VIII, #2, Radio Sampler, composed by Robert Maxwell, Oasis]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Thurston Briscoe, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. And we say goodbye to our intern Hannah Loss. Thanks so much for your hard work. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOEE dot org – and like us, please, on our Facebook page, PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Steve Curwood – thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and from the University of Massachusetts Boston in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong clean energy economy. And from Solar City, America’s solar power provider. Solar City is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth