Nobel Prize in Chemistry Recognizes Lithium Battery Discoveries

Air Date: Week of October 25, 2019

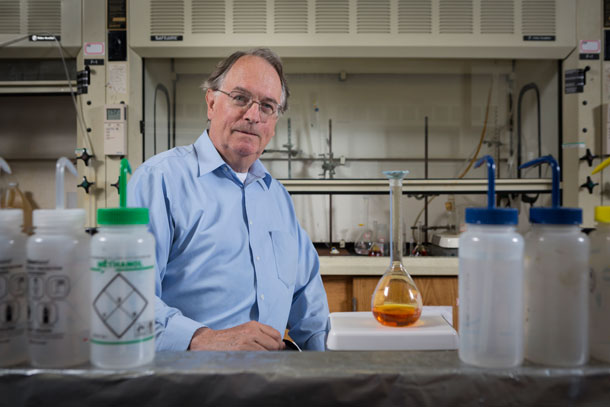

M. Stanley Whittingham is one of three recipients of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his groundbreaking work on lithium ion batteries. (Photos: Courtesy of Binghamton University)

Lithium ion batteries revolutionized much of the technology we rely on today. Smartphones, lifesaving defibrillators, and even some cars wouldn’t exist as we know them today without these batteries. This year, the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry commemorates the work of three scientists who helped develop the lithium ion battery. One of these recipients, Professor M. Stanley Whittingham, joined Host Jenni Doering to talk about his groundbreaking work.

Transcript

DOERING: From smartphones to electric cars, many of the technologies we rely on today would not be possible without the lithium-ion battery. And this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry recognizes the contributions of three scientists to the development of that technology back in the 1970s and 80s. One of the Nobel recipients is SUNY Binghamton Professor Stan Whittingham, who created the first functional lithium battery. He joins me now from Vestal, New York. Thank you for taking the time with me, Professor!

WHITTINGHAM: Thank you.

DOERING: And by the way, congratulations on receiving the Nobel Prize!

WHITTINGHAM: Thank you.

DOERING: So, your research gave rise to things like the batteries in cell phones, cardiac defibrillators, electric cars, so many things in our everyday lives. What has it been like to watch this technology that you helped develop become so integral to our modern world?

WHITTINGHAM: Well, amazing! We knew it was important when we got started almost 50 years ago now. But, our interest then was partly electric vehicles and partly toys, shall we say electronic toys, but we never envisaged it would take off to this magnitude and basically eliminate all other battery systems.

DOERING: So, let's go back to the 1970s for a minute. Could you please share with us what were you doing at the time and what led you to make your lithium battery discovery?

WHITTINGHAM: I'd been at Stanford University as a researcher, and then I went to Exxon to work on energy related research, but not oil or chemicals. They wanted to be an energy company, not just a petroleum company. So, we started looking at, um, superconductors and how to store energy and came across a reaction that generated a lot of heat. So, we said, hey, this can store energy. And then we started within weeks developing a very simple battery in the beaker on the bench top.

DOERING: Wow. So, what did it feel like when you made this discovery?

WHITTINGHAM: I don't think we realized how important it was. It was a simple experiment. We got the experiment going. I went to New York City to meet with committee of the Exxon board to explain it. You know, what they call elevator pitch these days, I guess. And they said within a few days, let's go ahead. So, we bought equipment to actually build real cells. They hired manufacturing folks to lead that team and then the end, they developed the battery, made some batteries, and things went great.

DOERING: So, you made this discovery, and then there were some wrinkles that needed to be worked out. I think namely that these lithium batteries could sometimes cause an explosion. So what happened next with the technology?

WHITTINGHAM: In the lab we never had any fires or explosions. We had fires when we pulled the cells apart to do basically post mortem studies on them. So there's finely divided lithium, that lithium caught fire. And I think the company got a bit upset after the fire trucks came in the front gate, two or three times. So, lithium is hazardous. And today, there's really no batteries that use lithium metal. So you have lithium ion batteries, that means there's only ions in the batteries.

DOERING: Let's talk a little bit about your co recipients of this Nobel Prize, who also developed lithium ion battery technology. So, I think you were the first of these three scientists to sort of move this technology forward. What happened next and what was the role of Dr. John Goodenough and Dr. Akira Yoshino.

WHITTINGHAM: So, at Exxon we developed the system and the concept of interpolation, which is the reaction where we put lithium in this material, it gave us about two and a half volts. So, we use the sulfide. John Goodenough was at Oxford. So, John came up what is called lithium cobalt oxide, that's four volts. So, he increased the voltage of the cell, which made it an, really a business economic reality. You know you can store twice as much energy and principle. But then we have the normal story of European and American discoveries that really industry in the US and America doesn't want to invest 10 years worth of work. And Dr. Yoshino's company, which was a carbon company, was willing to do this. They developed the carbon anode, so you don't have lithium metal, and built the first batteries and then they interacted with Sony. And then it was Sony actually commercialized it and put the products on the market.

Lithium ion batteries help power much of the technology that we use in everyday life. (Photo: Flickr, yuankuei CC)

DOERING: So, it's clear that lithium ion batteries have really paved the way to a society that's less dependent on fossil fuels by helping us replace gas field cars with electric ones, and even leading to the recent development of commercial electric airplanes. So how do you envision lithium ion batteries continuing to play a role in bringing about a more sustainable world?

WHITTINGHAM: There's no question that lithium ion batteries is going to be the main, I would say, portable storage medium. So we want vehicles, and then particular things like buses. I can envisage Boston, New York, San Francisco and big European cities saying no more internal combustion engines, you've got to run electric vehicles. But if you want solar and wind you've got to use storage, because the sun doesn't shine will you want electricity and the wind blows at nighttime, so you need storage to do that. And that is coming on faster at this time. So this will give us a more sustainable environment. We use the wind and the sun more, and we'll have a cleaner environment hopefully. So it's going to get rid of a lot of these what we call very dirty peaker plants, which are mostly coal and related.

DOERING: What do you think are the next steps for lithium ion batteries? And what kinds of improvements do you anticipate and hope for?

WHITTINGHAM: Well, right now I'm part of a large department of energy consortium to increase the energy density stored in them from 250 to 500 wattage per kilogram. So we're hoping to store twice as much energy in the same volume and the same weight as today. So, we can do that we'll have smaller batteries. At the same time, we hope to reduce the price of them by also by 50%. But those are all challenges. If we increase our efficiency, we use less cobalt less lithium, and we make them last twice as long than global use less than half the amount of lithium and cobalt. So lifetime and efficiency are two key things that help clean up the environment.

DOERING: Professor Stan Whittingham is a 2019 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Thanks so much for talking with me today!

WHITTINGHAM: Thank you.

Links

More about the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The New York Times | “Lithium-Ion Batteries Work Earns Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 3 Scientists”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth