October 25, 2019

Air Date: October 25, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Ethane Crackers Spark Pollution Concerns

View the page for this story

Plastic has long been made from oil, but today it’s increasingly made from ethane, a component of natural gas. To turn ethane into the building block of plastic, petrochemical companies are investing in ethane cracker plants. Judith Enck, founder of Beyond Plastics and visiting professor at Bennington College, joined Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss the concerns about what ethane crackers could mean for air pollution and climate change. (09:57)

BirdNote®: Red-Necked Phalaropes, Spinners On The Sea

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Some birds catch their food on the wing, snatching insects out of the air or plunging for fish in water. Others peck at trees or the ground to find grubs and worms but as BirdNote’s Michael Stein reports, an Arctic bird called the red-necked phalarope has a more unusual way to collect its dinner. (01:51)

Living Near The Coast Could Boost Mental Health

View the page for this story

Green spaces are known to provide physical and mental health benefits, and a recent study finds that living near the coast can provide the same benefit, especially for low income families. Joanne Garrett, the lead author in this study and a researcher at the University of Exeter's European Center for Environment and Human Health, joined Host Jenni Doering to talk about how blue space can benefit wellbeing. (06:07)

Oyster Shell Recycling

/ Kara HolsoppleView the page for this story

Fertilizer runoff can create massive algae blooms in water that suck up oxygen and creates dead zones for most other forms of life. The Chesapeake Bay is particularly vulnerable but as Kara Holsopple from Allegheny Front reports, restaurants in Pittsburgh are pitching in to help. (07:03)

Nobel Prize in Chemistry Recognizes Lithium Battery Discoveries

View the page for this story

Lithium ion batteries revolutionized much of the technology we rely on today. Smartphones, lifesaving defibrillators, and even some cars wouldn’t exist as we know them today without these batteries. This year, the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry commemorates the work of three scientists who helped develop the lithium ion battery. One of these recipients, Professor M. Stanley Whittingham, joined Host Jenni Doering to talk about his groundbreaking work. (06:27)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week's trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra and Host Bobby Bascomb take a look at the high levels of PFAS chemicals in grease-resistant fast food packaging. Then, the pair discuss the Rocky Mountain Steel Mill, which is pioneering the use of renewable energy in steelmaking. Finally, they look back to “Ozone Man,” President George H.W. Bush's nickname for Al Gore in the last throes of the 1992 election. (04:21)

‘Largest YouTube Collaboration Ever’ Aims to Plant 20 Million Trees

View the page for this story

Hundreds of YouTube creators partnered with the Arbor Day Foundation with a goal of planting 20 million trees. YouTuber Destin Sandlin, who runs the science-based channel “Smarter Every Day”, spoke with Host Jenni Doering to explain why these creators launched a movement seeking to rise above the noise of cat videos and memes. (10:46)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Judith Enck, Joanne Garret, Destin Sandlin, Stan Whittingham

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Kara Holsopple, Michael Stein

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Oil and gas companies are quietly shifting from one source of greenhouse gas emissions to another - plastic.

ENCK: Fossil fuel companies see that there’ll be reduced demand for fossil fuels, for electricity generation, and for transportation and so they are making a big money bet shifting to plastic production.

BASCOMB: Also, hundreds of YouTube creators collaborate on a call to action, encouraging young people to help plant 20 million trees.

SANDLIN: You hear a lot of disparaging things about the younger generation. And this is just a really straight up line in the sand. Like hey: There is something that needs to happen, so we're just going to do it. This is going to be the largest collaboration on Youtube ever. In the world.

DOERING: That’s this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Ethane Crackers Spark Pollution Concerns

Protesters uniting in August 2019 against President Trump’s visit to a Shell Ethane Cracker Plant in Western Pennsylvania. (Photo: Mark Dixon, NoPetroPA, Flickr, CC By 2.0)

DOERING: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, it’s Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Plastic. It’s not just a problem for overwhelmed landfills or the marine life that ingest it. Plastic is also a huge contributor to carbon emissions and climate change. Cradle to grave, plastic could produce as much as 56 gigatons of carbon dioxide between now and 2050, according to a recent study. That’s 50 times more carbon emissions than all the coal fired power plants in the United States produce in a year. Part of the reason plastic is so carbon intensive is that it’s made from fossil fuels. Historically the building block of plastic was oil but today it’s increasingly made from ethane, a component of natural gas. And to cheaply extract ethane petrochemical companies are investing in ethane crackers. Here to explain is Judith Enck, founder of Beyond Plastic and a visiting professor at Bennington College. Judith, welcome to Living on Earth!

ENCK: Thanks. It's a pleasure to be with you.

BASCOMB: Now what exactly is ethane? And what's an ethane cracker for listeners who maybe aren't familiar with those terms?

ENCK: Ethane is what is flared into the atmosphere when hydrofracking takes place. It's a very potent greenhouse gas. And right now at hydro fracking sites, it's just vented into the atmosphere. So the proposal by a number of petrochemical companies like Shell and Exxon and BP is they want to capture that ethane, send it by a pipeline and have it used at a new plastic producing factory they want to build called an ethane cracker plant. And what essentially happens there is the ethane is heated to a very high temperature. It's cracked, and it becomes a building block of plastic packaging. Because fracking has made gas cheap, it's driving this massive expansion in new infrastructure for plastics and petrochemicals. It will also discourage companies from using recycled plastic in their products, because the virgin plastic will be cheaper.

BASCOMB: Now, I understand that Shell is in the process of building a new ethane cracking facility in Pennsylvania and Exxon is scoping out sites for a plant in Ohio. These are fossil fuel companies getting involved in plastic. To what degree do you think maybe these companies see the writing on the wall about the continued use of fossil fuels in the light of climate change and I don't know maybe looking for alternatives in their product?

ENCK: You're absolutely right. Fossil fuel companies see that there'll be reduced demand for fossil fuels per electricity generation and for transportation, and so they are making a big money bet shifting to plastic production. They are counting on the world to wanting more and cheaper single use plastic packaging. You know, it's not a coincidence that a lot of these ethane cracker plants are proposed in Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Ohio, almost serving as a replacement for coal. They do not create many permanent jobs. They definitely create a lot of jobs during construction, but not many permanent jobs. So this is not really going to help us with a transition toward a more renewable energy future or a Green New Deal future because you're not going to get the benefit of much job creation here.

Less than one percent of plastic waste gets recycled posing a dangerous threat to sea life and human health. (Photo: Rey Perezoso, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: So the sights for a lot of these plants are in Appalachia, as you mentioned that's coal region of course of the country and in areas that are presumably already accustomed to dealing with a certain amount of pollution and industry in their communities. Do you think it's fair to say that that might have been part of the thinking for why these fossil fuel companies decided to cite their plants in this region?

ENCK: Yes, I think the petrochemical industry is looking to target communities that are economically struggling, and that are used to hosting highly polluting companies. Which is really too bad because it makes the environmental justice problem even worse, you've got overburdened communities that have been receiving massive amounts of pollution for years and so the plan is to just keep that going. It's very interesting that you do not see ethane cracker plants proposed in more affluent communities. They are proposed in communities that already have high levels of pollution and don't seem to have elected officials that are willing to stand up for public health.

BASCOMB: So what are some of the potential health issues associated with living near these industrial areas?

ENCK: One concern is large amounts of benzene, an air toxin is emitted. And you have other air contaminants that contribute to ground level ozone or smog, contaminants that can trigger asthma attacks. These are not good neighbors. And then on the global level, you've got large amounts of carbon dioxide being released into the atmosphere. These facilities are not proposed, where the CEOs of Shell and Exxon and SABIC, S-A-B-I-C live, these facilities are proposed, where poor people live where they believe these are communities of least resistance.

BASCOMB: Now, I understand that the United States is actually producing so much natural gas at this point that we're actually exporting it to some other countries to make their own plastic. Can you tell me about that?

ENCK: So yes, there is a glut of fracked natural gas on the domestic market. So some of that is being exported to Europe. And what I predict what will happen over the next 10 years is not only will the United States be exporting fracked gas, but there will be an uptick in the manufacturing of single use plastic packaging here and in other countries and we'll see just a dramatic increase of cheap plastic packaging circulating in the world.

BASCOMB: Well, the social trend is to do away with single use plastic, you know, there's plastic bag bans and plastic straw bans across the country, that sort of thing. But I guess the market is pushing us in a different direction.

Juidith Enck is founder of Beyond Plastics, visiting professor at Bennington College in Vermont and former Regional Administrator for Region 2 of the EPA. (Photo: Courtesy of Judith Enck)

ENCK: I think there's an amazing disconnect between the problem the fact that we have 9 million metric tons of plastic entering the ocean every year, and the makers of the plastic have no financial responsibility for what happens after the plastic is manufactured. So, at the local level across the United States, there are literally hundreds of new laws recently adopted that ban plastic bags or ban polystyrene foam for food or ban or more likely with straws, plastic straws only upon request. There's an incredible energy at the local level to reduce plastic pollution and at the same time, tax dollars are being used to promote the construction of ethane crackers. And the petrochemical industry is gearing up for a major increase in investments in this petrochemical build out and sadly, most Americans do not know this is happening.

BASCOMB: So what can be done then? I mean, how do we address this problem? It's pretty clear that consumers don't necessarily want to use single use plastic or at least understand the problem. But our government is encouraging otherwise.

ENCK: We need to stop public subsidies for the petrochemical industry, you know, not just for plastic production, but also fossil fuel extraction. Second, this is happening without much public knowledge. And I think if you were to pull most members of Congress, especially those that don't live in the district where these ethane crackers are proposed, I can almost guarantee that they don't know that this is happening. I think we need a moratorium on the construction of new ethane crackers until we can figure out exactly what the climate change impacts are and the local toxic air emissions are. We really owe this to the communities that are hosting these facilities. So I think a moratorium is in order. And third, I think that there should be a continued movement at the local level to ban single use plastic packaging in order to reduce demand. The irony there is if there is less use of plastic packaging in the United States, I think a lot of these companies will simply export the packaging to other countries. But I think it's taken decades to finally get some traction on moving toward renewable energy sources and cleaner transportation choices, and then to have that almost cancelled out by the proliferation of carbon emissions from ethane cracker facilities would really, really be problematic.

BASCOMB: Judith Enck is founder of Beyond Plastics and a visiting professor at Bennington College.

ENCK: Thanks for taking this time with me.

BASCOMB: My pleasure. Thanks so much for covering this important topic.

Related links:

- Climate Reality Project | “Ethane Cracker Plants: What Are They?”

- Judith Enck’s Organization - Beyond Plastics

- The New York Times | “A Giant Factory Rises to Make a Product Filling Up the World: Plastic”

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Red-Necked Phalaropes, Spinners On The Sea

You’re most likely to spot a red-necked phalarope on a shallow arctic lake. (Photo: Gregg Thompson)

DOERING: Some birds catch their food on the wing, snatching insects out of the air or plunging for fish in the water. Others peck at trees or the ground to find grubs and worms but as BirdNote’s Michael Stein reports, one Arctic bird has a more unusual way to collect its dinner.

BirdNote®

Red-necked Phalaropes, Spinners on the Sea

[Calls of Red-necked Phalaropes and sound of wind on the ocean]

Red-necked Phalaropes are sandpipers that make their living from the sea. They breed on the arctic tundra but then migrate to the open ocean, where they’ll stay through the winter, feeding on tiny crustaceans and other marine animals.

You’ll be lucky to ever see one of these little birds, but if you do it’ll probably be on a shallow arctic lake. Stay and watch for a bit and you may see the phalaropes’ wonderfully unique method of feeding.

The birds twirl on the surface like little ballerinas, spinning and pecking, again and again.

[Calls of Red-necked Phalaropes]

Red-necked phalaropes breed on the Arctic tundra, then migrate to the open ocean to live there through the winter. (Photo: USFWS)

As it spins, the phalarope forces water away from the surface, causing an upward flow from as deep as a foot below. And with this flow comes food. Little animals, like tiny fly larvae, are forced to the surface. Then the phalarope quickly opens its bill, creating another rapid movement that pulls its prey into the back of its mouth.

One of the rewards of observing birds closely is that you see the fascinating strategies they use to survive and thrive.

[Calls of Red-necked Phalaropes]

###

Written by Dennis Paulson

Producer: John Kessler

Managing Producer: Jason Saul

Editor: Ashley Ahearn

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Assistant Producer: Mark Bramhill

Narrator: Michael Stein

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by G. Vyn. Ambient sound by Kessler Productions.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2019 Tune In to Nature.org September 2012 / 2015 / 2019

https://www.birdnote.org/show/red-necked-phalaropes-spinners-sea

DOERING: For pictures, spin on over to our website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- This story on the BirdNote® website

- Watch a video of red-necked phalaropes spinning and feeding

- Audubon: red-necked phalarope

- More on the red-necked phalarope at BirdWeb

[MUSIC: Joshua Redman, “Alone In the Morning” on Moodswing, by Joshua Redman, Warner Bros]

BASCOMB: Coming up- Research finds living near the ocean can be good for your mental health. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joshua Redman, “Alone In the Morning” on Moodswing, by Joshua Redman, Warner Bros]

Living Near The Coast Could Boost Mental Health

The beautiful South West English coast. (Photo: Gerritt Burow, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

[OCEAN SOUNDS – KIDS PLAYING AT THE BEACH (Credit: Dasound on Freesound.org)]

DOERING: For many of us a day at the beach can leave us feeling relaxed and content. And new research published in the journal Health and Place confirms what we might have suspected- people living near the ocean have lower rates of mental health issues. And that’s especially true for lower income families. Here to explain is Joanne Garret, lead author of the study and a researcher with the European Center for Environment and Human Health at the University of Exeter. Joanne, welcome to Living on Earth.

GARRETT: Hi, thank you. Thanks for having me on your show.

DOERING: So what did you set out to find out in this study?

GARRETT: We previously found that people tend to be healthier living closer to the coast, and this was stronger for those living in the most deprived areas and we know how important mental health is. In the UK, one in six people are suffering from a mental health disorder at any one time. So we therefore wanted to explore whether that relationship observed with general health would be there for mental health as well.

DOERING: What were some of the social factors you looked at in terms of the differences between people of higher and lower incomes?

GARRETT: We took the mental health scores so people living at different distances from the coast. So we actually categorized them, so it was less than one kilometer, one to five kilometers, five to twenty, twenty to fifty, and more than fifty, and then we compared people who had the same incomes and we compared their mental health score. So we divided the population into five in terms of household income they have and then compared those on the lowest incomes at different distances from the coast, and then the same thing for those on higher incomes as well. We actually only included people who live in towns and cities because there's considerable differences between people experiencing nature and rural environments and towns and cities. There's also a lot of other factors that can be related to mental health such as access to services. So in this study, we really just wanted to focus on people in towns and cities.

The ocean can become a “safe zone” to lower income communities when it comes to mental health. (Photo: Guiseppe Milo, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: I understand that you did have some significant findings about coastal proximity and mental health. Can you tell me more about the main takeaways from your study?

GARRETT: So when we looked at the whole population, we found that those living within one kilometer from the coast were less likely to show symptoms of a mental disorder. But then when we broke it down by the household income, we found that that was only true for those with the least disposable income, and their protective zone extended up to five kilometers. And then for those with more disposable income, there was actually no relationship between how close they live to the coast and their mental health. There could be a lot of reasons to explain this, one of them might be that those with more disposable income, are better able to get to nature wherever it is how far away it's from their home. So they can afford bus tickets or they might have a car, whereas those who have less disposable income, having nearby nature is really beneficial. So for me that highlights how important having access to nature close to your home is for mental health.

DOERING: We've heard about the physical and mental health benefits of living near green space and having access to green space. So to what extent are there similarities between the health benefits of proximity to green space and coastal proximity?

GARRETT: Yeah, you're totally right. There's been a lot of research over the past recent decades looking at green spaces and mental health and health benefits. We think some of the same mechanisms behind that relationship also might explain the relationship between blue spaces, the coast but that is an area of ongoing research really. Other research has found links between having a view of blue space from the home, which has been linked to better mental health in countries around the world, and it also might be places to enjoy physical activity or socializing with friends and family.

DOERING: This is making me think of this idea of biophilia that I think E. O. Wilson has talked about where, you know, we evolved to, like certain green spaces…

GARRETT: Yeah.

DOERING: And maybe blue space as well because of its benefits to our society throughout all of our evolutionary history. Can you talk a little bit about that as a possible influence on how we feel? Why do we feel so good around blue and green spaces?

Joanne Garrett, lead author of the study on the mental health effects of blue space. (Photo: Courtesy of Joanne Garrett)

GARRETT: Yup, biophilia is one theory that might explain the mechanisms between interacting with nature and our mental health. There are a couple of others that we use and when we research scientifically as well. One's called attention restoration theory. So when we're walking around a busy urban environment, it actually takes quite a lot of energy, quite a lot of mental capacity to navigate your way around the city and then when we're in nature, that is kind of restored. The environment is not so stressful in terms of the noise and the business but is also engaging, allowing us to sort of naturally restore our cognitive abilities. And the other one is a stress reduction theory where being in nature reduces the physiological signs of stress.

DOERING: Could we maybe see the same effects for freshwater proximity, not just living near the coast?

GARRETT: Yep, that is absolutely possible, and some countries might not have access to the coast at all it might be a landlocked country. So, I actually work on a project called Blue health, which is a Pan European project. And we're looking at this question exactly. We've got survey results from 18 different countries, mostly in Europe, but also includes California in the USA. And we asked people what types of blue spaces do they visit and how they felt about their visit. And we also asked what did they do and how long they spent there so we can take into account those factors as well. Other strands of work include exploring whether virtual reality can be used to take blue spaces to people who can't get outside. And the focus is really on elderly people living in care homes. And we've explored different kinds of blue spaces. So just using three-sixty video footage, some of which was recorded on our beaches in Como, and our colleagues from Lund's University have explored using computer generated blue spaces and taking that into care homes as well as seeing what the effect of that might be.

DOERING: Joanne Garrett is a researcher at the University of Exeter's European Center for Environment and Human Health. Thanks so much, Joe.

GARRETT: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Mother Nature Network | “Living Near the Coast is Linked with Better Health, Study Suggests”

- Click here to read Joanne Garrett’s Study

[MUSIC: Norah Jones, “Sinkin’ Soon” on Not Too Late, by Norah Jones, EMI]

Oyster Shell Recycling

Chesapeake Bay oysters wait to spawn. (Photo: Kara Holsopple, The Allegheny Front)

BASCOMB: Well, living near blue spaces may be good for our health but in many cases our oceans and waterways are not in very good health themselves. The Chesapeake Bay is routinely inundated with fertilizer runoff from the surrounding watershed in parts of Pennsylvania and Maryland. The result is algae blooms that suck up oxygen in the water and create dead zones for most other forms of life in the Bay. Oysters are particularly vulnerable but as Kara Holsopple of The Allegheny Front reports some local groups have come up with a novel way to help oysters recover.

[AMBI RESTAURANT KITCHEN]

HOLSOPPLE: Jessica Lewis says shucking an oyster is like picking a lock...

LEWIS: You press down and then you just wiggle, pop it open and, the abductor muscle right there. You clean that.

HOLSOPPLE: Lewis is the executive chef of Spirits & Tales at the Oaklander Hotel in Pittsburgh. She runs a small knife around the sides of a closed oyster shell...

[NAT POP SOUND]

Jessica Lewis, executive chef of Spirit & Tales at the Oaklander Hotel in Pittsburgh, prepares oysters. (Photo: Kara Holsopple, The Allegheny Front)

LEWIS: You can't really muscle through it. You clean under it and see all that liquor? This one’s got a lot of liquor in it.

HOLSOPPLE: That’s the salty ocean water still inside the shell, and it makes the oyster slide out smoothly...into your mouth...

LEWIS: That's perfect. I'm going to take this one right here.

HOLSOPPLE: Lewis says they go through about three to four hundred oysters here a week...from the East and West coasts. This oyster is from Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay...and its top and bottom shell are going back there…

[AMBI OUTSIDE NOISE/TRUCK]

Lewis and her staff toss the spent shells in a 35 gallon barrel with a screw-on lid, located in the trash area on the ground floor of the building.

LEWIS: So, nobody likes to recycle the oyster shells because there's flies everywhere and it's nasty. Gross

LEWIS: But we're doing something good. Let's get out of here.

[AMBI OUTDOORS/TRUCK OUT]

HOLSOPPLE: About once a month a truck picks up the old shells from this and six other participating restaurants in Pittsburgh, and drives them more than 250 miles to a staging area just across the Chesapeake Bay Bridge in Maryland.

From there, the oyster shells from Pittsburgh, and ones collected from Maryland, Virginia and the D.C. area are taken to a site at the University of Maryland’ Horn Point Laboratory in Cambridge, for processing.

[AMBI OUTDOOR]

KING: “So here you’re looking at about 7K tons of clean shell…”

HOLSOPPLE: Karis King is with Oyster Recovery Partnership, a nonprofit which works to increase oyster numbers in the Chesapeake Bay. We’re standing at the base of a mountain of gray shells.

They’ve been dumped into a machine that’s like a modified potato hopper, which sorts the shells...

[NAT SOUND OF SHELLS DUMPED]

And washed with water from the nearby Choptank River...a major tributary of the bay. Smaller fragments of broken shell fall away as a conveyor belt deposits the half shells into wire cages or piles where they’re cured for a year.

[NAT SHELL ON BELT]

Then they’re ready to go on to the next phase of the recycling chain...

KING: even with all the shell that we do recycle, and that we also purchase from shucking houses, we still don’t have enough to do large scale restoration, at the rate that we could.

[AMBI OUTDOORS OUT]

HOLSOPPLE: That’s because of the scale of the problem. Stephanie Alexander manages the Horn Point Lab oyster hatchery.

ALEXANDER: When John Smith sailed up in the 1600s he was running aground on oysters...

HOLSOPPLE: Alexander says that’s before these waters were overharvested, before there was agricultural runoff and soil erosion from development...

ALEXANDER: We've pretty much wiped the oyster out to less than 1 percent of historic levels. So we started this restoration effort where we're using a hatchery to produce spat on Shell to put back into the bay so we can kind of help jump start Mother Nature.

HOLSOPPLE: The concept is pretty simple: Scientists here at the lab produce baby oysters from adults harvested from the bay, nurture the microscopic larvae with a custom algae diet, then get them attach to the recycled, treated oyster shells...that’s the ‘spat on shell.’

In practice, it’s a lot harder than it sounds…

[AMBI LAB]

Ben Malmgren is an intern here, a student from St. Mary's College of Maryland.

[NAT PLACING OYSTERS]

MALMGREN: Right now we're placing the oysters out on the spawning table where we are going to simulate river conditions that are ideal for spawning.

[NAT WATER]

HOLSOPPLE: The saltiness and temperature of the water in the shallow black basins has to be just right. Malmgren places the oysters in a grid formation, so it’s easier to separate the males from the females…

MALMGREN: Because if we just let them spawn out on the table all these eggs are gonna go down to the into the drain. So once we see a female and we'll we'll know she's a female by she'll clap her top and bottom shell together and we'll see a plume of eggs come out and kind of look like Splenda like in a cup of coffee.

HOLSOPPLE: Then he’ll pull the females off the table, where they’ll continue to spawn in a tub. Those eggs will be fertilized with the sperm collected from the male oysters. But the oysters aren’t cooperating today…Left to their own devices, it could take hours...

MALMGREN: It's a lot like just watching a pile of rocks but can be exciting when they all start going.

[AMBI LAB WATER OUT]

[AMBI LAB]

Stephanie Alexander manages the Horn Point Lab oyster hatchery. (Photo: Kara Holsopple, The Allegheny Front)

HOLSOPPLE: Even in the lab, nature is in charge. Stephanie Alexander says it was a slow summer...a lot of rain meant the adult oysters have lived with lower salinity levels, and they’re stressed. Out in the bay, the water is warmer, meaning the spat on shell might have a harder time growing that second shell, and over the years, forming the clusters that create oyster reefs.

ALEXANDER: When one thing gets out of whack everything else is going to kind of follow. So we're trying to get the oysters back into balance so then hopefully everything else will follow as well.

HOLSOPPLE: Over the last 2 decades, the lab and Oyster Recovery Partnership have planted over 8 billion oysters on the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, with the help of other partners like the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Throughout the summer spat on shell are released from a boat on sites where they’re most likely to survive. And Alexander says that’s critical…

ALEXANDER: Oysters are the vacuum cleaners or the kidneys of the bay and they just suck the water in, they decide if it's food or not food. But no matter what it is that will remove it from the water column and that's how they vacuum the bay up and clean it.

HOLSOPPLE: Because of this superpower, oyster aquaculture is a best management practice identified by the regional partnership that oversees cleaning up the Chesapeake Bay.

Some of the spat raised at the Horn Point Lab will make its way to oyster farmers, and those are the oysters on a half shell that are served in restaurants. But the majority of the spat will help rebuild oyster reefs, creating habitat for fish, and restoring the ecosystem.

[RESTAURANT AMBI]

BACK IN PITTSBURGH, Jessica Lewis is educating diners and trying to convince other Pittsburgh restaurants to join the oyster shell recycling effort that feeds the conservation work... to see the value in giving back...

LEWIS: With all this like climate change going on and all those scary things it's like a bright light shining through...that we did something good.

HOLSOPPLE: Her pitch: Every shell counts.

BASCOMB: Kara Holsopple’s story comes to us courtesy of State Impact Pennsylvania, a collaboration of public media outlets covering Pennsylvania's energy economy.

Related links:

- Hear this story on the Allegheny Front website

- Learn more about oyster restoration in the Chesapeake Bay

- This story was produced in partnership with StateImpact Pennsylvania

[MUSIC: Lila Downs, “Sale Sobrando” on Border, by Lila Downs, Narada World]

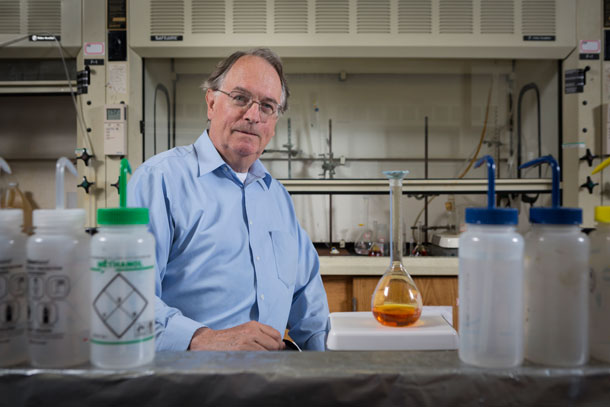

Nobel Prize in Chemistry Recognizes Lithium Battery Discoveries

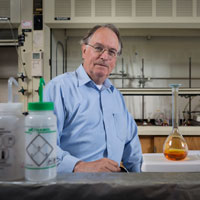

M. Stanley Whittingham is one of three recipients of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his groundbreaking work on lithium ion batteries. (Photos: Courtesy of Binghamton University)

DOERING: From smartphones to electric cars, many of the technologies we rely on today would not be possible without the lithium-ion battery. And this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry recognizes the contributions of three scientists to the development of that technology back in the 1970s and 80s. One of the Nobel recipients is SUNY Binghamton Professor Stan Whittingham, who created the first functional lithium battery. He joins me now from Vestal, New York. Thank you for taking the time with me, Professor!

WHITTINGHAM: Thank you.

DOERING: And by the way, congratulations on receiving the Nobel Prize!

WHITTINGHAM: Thank you.

DOERING: So, your research gave rise to things like the batteries in cell phones, cardiac defibrillators, electric cars, so many things in our everyday lives. What has it been like to watch this technology that you helped develop become so integral to our modern world?

WHITTINGHAM: Well, amazing! We knew it was important when we got started almost 50 years ago now. But, our interest then was partly electric vehicles and partly toys, shall we say electronic toys, but we never envisaged it would take off to this magnitude and basically eliminate all other battery systems.

DOERING: So, let's go back to the 1970s for a minute. Could you please share with us what were you doing at the time and what led you to make your lithium battery discovery?

WHITTINGHAM: I'd been at Stanford University as a researcher, and then I went to Exxon to work on energy related research, but not oil or chemicals. They wanted to be an energy company, not just a petroleum company. So, we started looking at, um, superconductors and how to store energy and came across a reaction that generated a lot of heat. So, we said, hey, this can store energy. And then we started within weeks developing a very simple battery in the beaker on the bench top.

DOERING: Wow. So, what did it feel like when you made this discovery?

WHITTINGHAM: I don't think we realized how important it was. It was a simple experiment. We got the experiment going. I went to New York City to meet with committee of the Exxon board to explain it. You know, what they call elevator pitch these days, I guess. And they said within a few days, let's go ahead. So, we bought equipment to actually build real cells. They hired manufacturing folks to lead that team and then the end, they developed the battery, made some batteries, and things went great.

DOERING: So, you made this discovery, and then there were some wrinkles that needed to be worked out. I think namely that these lithium batteries could sometimes cause an explosion. So what happened next with the technology?

WHITTINGHAM: In the lab we never had any fires or explosions. We had fires when we pulled the cells apart to do basically post mortem studies on them. So there's finely divided lithium, that lithium caught fire. And I think the company got a bit upset after the fire trucks came in the front gate, two or three times. So, lithium is hazardous. And today, there's really no batteries that use lithium metal. So you have lithium ion batteries, that means there's only ions in the batteries.

DOERING: Let's talk a little bit about your co recipients of this Nobel Prize, who also developed lithium ion battery technology. So, I think you were the first of these three scientists to sort of move this technology forward. What happened next and what was the role of Dr. John Goodenough and Dr. Akira Yoshino.

WHITTINGHAM: So, at Exxon we developed the system and the concept of interpolation, which is the reaction where we put lithium in this material, it gave us about two and a half volts. So, we use the sulfide. John Goodenough was at Oxford. So, John came up what is called lithium cobalt oxide, that's four volts. So, he increased the voltage of the cell, which made it an, really a business economic reality. You know you can store twice as much energy and principle. But then we have the normal story of European and American discoveries that really industry in the US and America doesn't want to invest 10 years worth of work. And Dr. Yoshino's company, which was a carbon company, was willing to do this. They developed the carbon anode, so you don't have lithium metal, and built the first batteries and then they interacted with Sony. And then it was Sony actually commercialized it and put the products on the market.

Lithium ion batteries help power much of the technology that we use in everyday life. (Photo: Flickr, yuankuei CC)

DOERING: So, it's clear that lithium ion batteries have really paved the way to a society that's less dependent on fossil fuels by helping us replace gas field cars with electric ones, and even leading to the recent development of commercial electric airplanes. So how do you envision lithium ion batteries continuing to play a role in bringing about a more sustainable world?

WHITTINGHAM: There's no question that lithium ion batteries is going to be the main, I would say, portable storage medium. So we want vehicles, and then particular things like buses. I can envisage Boston, New York, San Francisco and big European cities saying no more internal combustion engines, you've got to run electric vehicles. But if you want solar and wind you've got to use storage, because the sun doesn't shine will you want electricity and the wind blows at nighttime, so you need storage to do that. And that is coming on faster at this time. So this will give us a more sustainable environment. We use the wind and the sun more, and we'll have a cleaner environment hopefully. So it's going to get rid of a lot of these what we call very dirty peaker plants, which are mostly coal and related.

DOERING: What do you think are the next steps for lithium ion batteries? And what kinds of improvements do you anticipate and hope for?

WHITTINGHAM: Well, right now I'm part of a large department of energy consortium to increase the energy density stored in them from 250 to 500 wattage per kilogram. So we're hoping to store twice as much energy in the same volume and the same weight as today. So, we can do that we'll have smaller batteries. At the same time, we hope to reduce the price of them by also by 50%. But those are all challenges. If we increase our efficiency, we use less cobalt less lithium, and we make them last twice as long than global use less than half the amount of lithium and cobalt. So lifetime and efficiency are two key things that help clean up the environment.

DOERING: Professor Stan Whittingham is a 2019 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Thanks so much for talking with me today!

WHITTINGHAM: Thank you.

Related links:

- More about the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

- The New York Times | “Lithium-Ion Batteries Work Earns Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 3 Scientists”

[MUSIC: Childsplay/Matt Glaser, “Bob’s Child – Golden Earring” on Twelve Gated City, by Matt Glaser/Jay Livingston & Victor Young, Childsplay Music]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Ozone man and other slurs against environmentalists in our weekly trip Beyond the Headlines. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Childsplay/Matt Glaser, “Bob’s Child – Golden Earring” on Twelve Gated City, by Matt Glaser/Jay Livingston & Victor Young, Childsplay Music]

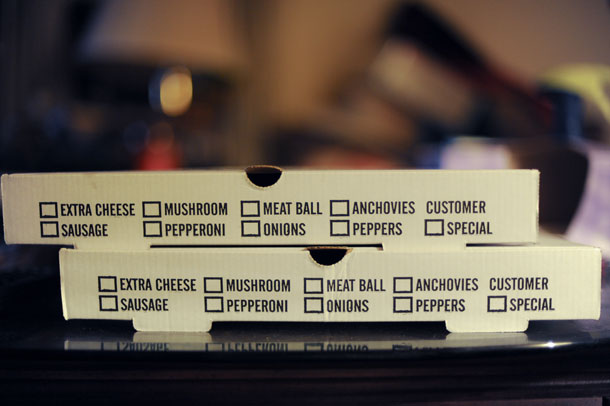

Beyond the Headlines

Pizza boxes are one example of fast food’s grease resistant packaging, which contains PFAS chemicals and potentially poses a threat to human health. (Photo: Eddie Welker, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth I’m Jenni Doering.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

And it's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby. Well, how'd you like some PFAS with your pizza? There's a study that says that people who eat more takeout food have higher levels of the harmful chemicals known as PFAS in their bodies. That comes from things like pizza boxes and burger wrappers and food packaging that's designed to be grease resistant.

BASCOMB: Oh, man. And what are PFAS and what are the potential health problems associate with PFAS chemicals?

DYKSTRA: It's a family of fluorinated chemicals called the "forever chemicals" because they don't break down. They're possible cancer-causers. It's also used in things like nonstick pans, other cooking utensils, a lot of non-food applications. The nation of Denmark has already banned PFAS chemicals from use in any food packaging. And some Individual US states are taking up the banner as well, and maybe bringing restrictions soon.

BASCOMB: All right, well, let's hope so. What else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Go back to 1881. There's a steel mill in Pueblo, Colorado, the Rocky Mountain Steel Mill, whose history is hand in hand, the history of the development of the American West, or stealing the American West from the Indians. The Rocky Mountain Steel Mill was the main source of steel rails for the railroads that were built all over the West in the back half of the 19th century, early 20th century. That steel mill that's been in business for well over 100 years, is going to finally ditch the use of coal. Coal is universal in powering those very, very hot steel furnaces. But the Rocky Mountain Steel Mill, a pioneer in its field over a century ago, is now going to be a pioneer by using solar and wind energy as the main source for heating its furnaces.

BASCOMB: Well, that's great. But why are they making this switch after such a long history with coal?

DYKSTRA: Well, you might think it was climate change. It isn't. You might think it was pollution from coal and coal mining. It isn't. It's a simple matter of business economics. Throughout the world and throughout the production cycle, solar and wind and other renewables are now getting to be cheaper than coal.

Part of Pueblo’s Rocky Mountain Steel Mill in 2010. The mill is being updated with the addition of a solar array to provide renewable energy. (Photo: Plazak, Wikipedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

BASCOMB: Well, hey, that's encouraging. What do you have for us in the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: Turning the clock back to another presidential campaign, October 29, 1992. President George H.W. Bush was on the brink of losing his reelection to Bill Clinton and Clinton's vice presidential candidate Al Gore. President Bush went on the attack. He called Al Gore 'Ozone Man' and ridiculed his environmental advocacy.

BASCOMB: Hmm. And you know, I think we actually have a clip of that. Let's have a listen.

PRESIDENT GEORGE H.W. BUSH: You know why I call him 'Ozone Man?' This guy is so far off in the environmental extreme, we'll be up to our neck in owls and out of work for every American. This guy's crazy. He is way out, far out, man.

DYKSTRA: You know, the thing that's striking about that clip is that four years earlier, when George H.W. Bush was first elected president, he promised to be the environmental president. And in the span of one presidential term, he went from embracing environmental values to ridiculing them.

BASCOMB: Man. Well, some things never change. I mean, today, Greta Thunberg is being vilified for trying to protect the environment. But you know, I read the other day that the ozone hole has actually shrunk to its smallest size on record. So, maybe Ozone Man was onto something there.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, being called Ozone Man is not such a bad thing. It's one of the biggest environmental triumphs, through international cooperation, and the Montreal Protocol, the treaty that banned ozone-depleting chemicals. It's something that was actually endorsed and worked for by the Ronald Reagan administration, including then Vice President George H.W. Bush.

BASCOMB: It just goes to show that if we have the political will, these huge problems can be addressed and solved.

DYKSTRA: Right.

BASCOMB: Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks, Peter, we'll talk to you again soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on these stories on our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | “PFAS With Your Pizza? People Who Eat More Takeout Have Higher Levels of Harmful Chemicals in Their Bodies”

- The New York Times | “The Steel Mill That Helped Build the American West Goes Green”

- Click here to hear President George H.W. Bush’s campaign speech, with “Ozone Man” remarks around the six-minute mark

[MUSIC: Matt Glaser, “Turkey In the Straw” on Play Fiddle Play, traditional/arr.Manson, Flying Fish Records]

‘Largest YouTube Collaboration Ever’ Aims to Plant 20 Million Trees

The collaboration started when YouTuber Mr. Beast (Jimmy Donaldson) hit 20 million subscribers. (Photo: Night Media)

DOERING: YouTube.com. With over a billion views every day it’s en route to surpass television as America’s most-watched platform. It’s home to cat videos

(MEOW)

DOERING: Memes

(CHARLIE THAT REALLY HURT)

DOERING: And it’s the only place a kid’s song about sharks could garner nearly 4 billion views

(BABY SHARK DOO DOO DOO DOO DOO DOO)

DOERING: But YouTube is also home to a new kind of celebrity. Influencers.

(GOOD MORNING LOGANG, WHAT’S POPPIN’, HELLO IT’s GRAHAM HERE, WHAT IS UP MY CHICKPEAS)

DOERING: They make videos on nearly any topic imaginable from applying makeup to fixing home appliances. But most YouTube celebrities have never made a video about the environment. Until now. On October 25, in what’s being called the largest YouTube collaboration of all time, hundreds of YouTubers from around the world came together and used their combined influence to send a message on the environment.

(CLIP: OUR INSANE GOAL IS TO PLANT 20 MILLION TREES BY 2020. I’m STOKED LET’S PLANT SOME TREES. WE ARE PROUD MEMBERS OF TEAM TREES.)

DOERING: These YouTubers have a combined subscriber count of more than a billion people. One of the most popular YouTubers and an organizer of the event is Mr. Beast who posted a video of himself and a team of volunteers planting trees.

[And we put it in the hole…. now we need mulch…. put the mulch around the tree. Then we hydrate it. And there we go]

DOERING: Another YouTuber, Destin Sandlin, helped recruit fellow YouTube creators. Destin’s science education channel, Smarter Every Day, has 7.3 million subscribers and his content has amassed more than 660 million views. He joins me from Huntsville, Alabama. Destin, welcome to Living on Earth.

SANDLIN: Thank you so much for having me.

Destin Sandlin helped recruit YouTubers to join the initiative. Sandlin runs a science-based YouTube Channel, Smarter Every Day. (Photo: Destin Sandlin)

DOERING: Alright, so first, tell me about this collaboration-- what kinds of videos are being featured?

SANDLIN: Okay, so there's a ton of different creators from all over the internet coming together. I mean, there's hundreds, literally hundreds of creators on this list and they all have millions and millions of followers. There's people that have beauty channels, vlogging channels, we have science creators, education-type creators, people that do challenges. All these creators are coming from different places all over YouTube and the rest of the internet to work together on this one thing: We want to make an impact for good. We're calling it Team Trees. And we're going to support the Arbor Day Foundation and try to donate $20 million. And the Arbor Day Foundation has agreed that for every $1 that is donated to them, they will plant one tree, which is so cool.

DOERING: How did this big, huge collaboration among different influencers and creators actually get started?

SANDLIN: That was from the internet itself. When Jimmy, Mr. Beast's, when he passed 20 million subscribers. He likes to do different things when he gets a certain level of subscribers.

MR. BEAST: When I hit 3 million subscribers, I gave him 3 million pennies. When I hit 4 million subscribers, I gave him 4 million cookies. 5 million subscribers was 5 million pieces of popcorn.

SANDLIN: Everybody on Twitter and Reddit were telling him to plant 20 million trees. And he's like, "How the heck am I going to do that? That's that's a huge task." But he decided to basically reach out and get help. And so there was this little Twitter storm that happened one particular day, and everybody jumped in on it. They're like, "Oh my gosh, we could actually do this." So there was this video that was created behind the scenes. It was a secret video that was invite only. You can make a video unlisted on YouTube. And this was pushed out to a bunch of different creators, and it included a lot of really big creators in it all the way up to PewDiePie, right?

PEWDIEPIE: Of course, Mr. Beast I am by your side. I will plant at least a couple of trees.

SANDLIN: So we, we made this little secret video to encourage other creators to participate. And so once you watch it, you're just so and you're like, "Holy cow." This is bigger than any one YouTube channel. This is bigger than any one genre even.

GRASLIE: Think about all the birds that are going to have new homes next year.

HEVESH: I'm going to be building a giant tree out of thousands of dominoes than knocking it down and playing it in reverse. So you can see it build itself back up.

ROBER: Team trees assemble!

Mark Rober, another co-organizer of the event, made a video about planting trees with drones (Photo: Mark Rober)

DOERING: What do you expect viewers to come away with after they watch these videos that are being produced by all these creators?

SANDLIN: We hope that they realize that the viewers have the power to actually do things themselves. You know, a lot of times we think about these issues, and we're like, oh, that's another person's problem. It's not. It's all of our problems. So if we can come together and literally do something, it's an empowering message, right?

DOERING: And you're not competing with each other.

SANDLIN: No, not at all, like, to succeed is for everyone to succeed, right? Because it's the Earth, right? Like if we're all helping the Earth, that's like all being on the same bus and rooting for the bus driver to do well. We want the Earth to succeed. And so you know, there's a lot of policies that, you know, we see a lot of campaigns. But what we want to do is physically and tangibly do a real thing that helps the environment. And that is putting trees in the ground.

DOERING: So what do you think it is about YouTube as a platform that can make a project like this possible?

Mr. Beast and their crew planted hundreds of trees in Oregon for their #TeamTrees video. (Photo: Night Media)

SANDLIN: So a lot of people have different opinions about YouTube. For me, it feels like this repository of knowledge that all humans can go to and learn whatever it is they want to learn. And that's what YouTube is for me. And there's also a community that builds around that like whatever topic it is: if you want to learn how to repair cars, if you want to learn how to, you know, how to operate a laser cutter, whatever it is, there is a community there for you. And what's so cool about this specific thing is that all of these communities in this one moment, they're coming together, and this is like, it's like a bunch of different circles in this really massive Venn diagram and right at the center of all of those is that we all live on Earth and we all want earth to be better.

DOERING: I understand that some creators have even made songs just for this occasion. Let's listen to a clip.

BROWN: Is there anything better than the tree? If you ask me it ain't that hard to see. How about 20 million, 20 million trees. Making 20 trillion little baby leaves. And I can't help but choke up thinking about all the birds and bees.

Mr. Beast and his team of tree-planting volunteers. (Photo: Night Media)

SANDLIN: What we just heard is from a guy named Gabriel Brown. He's a creator that was in the Navy. He's a veteran. But now he makes music videos. He does all kinds of stuff on YouTube. And he decided to make a song for this movement. And I think it's really good. And there's other creators that are making songs as well.

DOERING: Wow. So tell me a little bit about what your video for this collaboration is about.

SANDLIN: So everybody's making their own video about trees, or at least shouting out the fact that we're doing this and so my video in particular is about why certain species of trees grow in certain regions. So a long time ago, my grandfather tried to plant a whole field of what's called the long leaf pine. I live in Alabama. And I'm right on the edge of where the long leaf pine can survive. And so he planted 200 trees with the help of Auburn University and they failed. And that was back in the 60s. And so what I did is I went back to Auburn University and talked to them about why it failed. And then they taught me more about the long leaf pine in particular and how it loves fire. You know, it's one of the species that fire actually helps it in its local ecosystem. So I learned about that specific tree. And then I use that as a way to explain that everybody has a certain tree, if they're not in the desert, they have a certain tree that thrives where they're at.

DOERING: You know, most people on YouTube, I think, are sort of a younger generation. And we've seen a lot of this youth movement on climate action recently. To what extent do you feel connected to that other part of activism on the environment?

SANDLIN: Well, I think it's awesome, because you hear a lot of disparaging things about the younger generation. And this is just a really, really straight up line in the sand like, hey, there's something needs to happen. So we're just going to do it. We're not going to wait for policies, or we're not going to wait for anything like that. We're just going to do things because we know how and we're able to. But that being said, it's not limited to the younger generation. I mean, this is everybody. Like we want no boundaries, no borders on this at all. It's it's all we and us, and we're all planting trees, which is awesome. Have you ever physically planted a tree?

Destin’s video is about how different trees are adapted to different regions. (Photo: Destin Sandlin)

DOERING: I actually don't think I have...

SANDLIN: What? You're on this radio show and you've never physically planted a tree? It's like a rush. Let me tell you a story. I got a tree in my Happy Meal back when I was six years old, and we planted it at my granny's house.

DOERING: Wait, in your Happy Meal?

SANDLIN: Yeah, there was there was the Arbor Day that they gave away pine trees down in the south in your Happy Meal. And I went and planted my tree beside my two cousins. They had trees as well. And we still go by that house today. And we look at this tree and it's huge. And knowing that I had a part in planting it so long ago is amazing. So I really think that planting trees is awesome, as long as you know exactly what you're doing, make sure you you make a decision, an informed decision on what to do and how to do it and just put a tree in the ground. It's awesome.

DOERING: Wow. And it'll live on for decades, maybe even hundreds of years.

SANDLIN: Yeah, yeah, that's why I'm interested in a long leaf pine because it is an old tree, like they can grow to be three or 400 years old. And we don't have a lot of old growth forests anymore. So I'm really interested, and this is just me talking right now, I'm specifically interested in planting trees that will live for a really long time. And so I'm going to be looking into how to do that.

DOERING: So Destin, when you first heard about this collaboration, why did you decide to join? Why does this matter to you personally?

Destin’s video is inspired by his grandfather’s failed tree planting with Auburn University in the 1960s. His grandfather is featured in the episode. (Photo: Destin Sandlin)

SANDLIN: I think everybody deep down, when you think about your time here on Earth, you want to be the kind of person that added good to the world instead of taking away and so you think about all the trees that are cut down on your behalf for the consumable products that you make or use or whatever. And, you know, I just want to be the kind of person that when I left, the Earth was a little more green than when I got here, that's what I want.

DOERING: What does it really mean to have a platform as huge as YouTube and these other platforms on the internet engaged in this kind of big collaboration?

SANDLIN: One of the things about being a YouTuber or an influencer is a lot of kids today want to be that. They want to have you know, that fame or whatever it is. And I think a lot of that can be dangerous because you're kind of turning the attention on yourself. And so I think another kind of secondary message that's being told here is it's about more than just you yourself. It's about everybody together. We're all in this together. And so that's what's so amazing about this particular collaboration. This is going to be the largest collaboration on YouTube ever in the world. It doesn't even matter how many subscribers the channel has. The important thing is looking outward beyond yourself and in trying to do good for others.

Destin’s channel, Smarter Every Day has 7.3 million subscribers. (Photo: Mark Schierbecker, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DOERING: Destin Sandlin Is a YouTuber who runs the science-based channel, Smarter Every Day. Thanks so much, Destin.

SANDLIN: It's been a blast. Thank you so much, Jenni.

DOERING: For links to the YouTube videos check out our website loe.org.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Team Trees initiative

- Destin’s YouTube Channel, Smarter Every Day

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck/Zakir Hussain/Edgar Meyer/The Detroit Symphony Orchestra/Leonard Slatkin, “Bubbles” on The Melody of Rhythm, by Bela Fleck, Koch]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Jake Rego engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth