Australia's Wildfires Point to the Future

Air Date: Week of January 10, 2020

The 2019-2020 fires in Australia have burned through about a third of Kangaroo Island, a haven for rare wildlife. (Photo: robdownunder, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Australia is in the throes of its worst fire season in modern history. As thousands of homes are incinerated and an estimated billion animals perish, the world is getting a glimpse of our future in a warming world. Penn State University climatologist Michael Mann joins Host Steve Curwood from Sydney, where he is taking a sabbatical to study the influence of climate change on extreme weather events. Prof. Mann explains the clear link between climate disruption and wildfire disasters, and discusses Aussies’ frustration with the response of their government to the climate crisis.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The land ‘down under’ has turned into a hellscape in recent weeks. Thousands have fled massive fires driven by years of drought and extreme heat on Australia’s south-east coast. ABC reporter Maggie Rulli was on the ground in the midst of the fires.

RULLI: Tonight, the dire warnings from Australia’s prime minister. The worst fire disaster in the country’s history could go on for months. Apocalyptic scenes, the infernos now forcing the largest peace time evacuation ever. The winds here just keep picking up it is fueling these flames. You can feel the smoke stinging your eyes. You can feel that heat off the fire. It is radiating right now. It is absolutely incinerating all of this brush all of these trees. Many of these are going to go at any second.

CURWOOD: Climate scientists say there is a clear link between climate change and the extreme drought and heat conditions that are helping to fuel the deadly fires. For more, we’re joined now by Michael Mann, a professor of atmospheric science at Penn State who just started a sabbatical in Sydney to study the linkages between climate change and extreme weather events. Hey Michael, welcome back to Living on Earth, and we’ve reached you in Sydney, is that right?

MANN: Yes, I'm in fact in Coogee Beach, just south of Sydney, looking out over the Pacific Ocean as I talk to you.

A burned-out Australian forest after a bushfire (Photo: Elizabeth Donoghue, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And you're there on a sabbatical, Professor Mann, but a bit of a busman's holiday. I mean, as a climate scientist, you are going to part of the universe that's really seeing some of the more devastating effects of drought and climate disruption, huh?

MANN: Well, that's right. Ironically, because the research agenda was determined well over a year ago, I'm here to study the impacts of climate change on extreme weather events in Australia. And it turns out that my sabbatical now coincides with perhaps the most profound episode of extreme weather that Australia has ever seen. When I arrived, I did have an opportunity to do a little bit of vacationing with my family. We went up to see the Great Barrier Reef while we still can, because of course it is threatened by bleaching from warming ocean waters and ocean acidification. And then we went to see another one of Australia's great wonders, the Blue Mountains, which are these vast expanses of temperate rainforest that are framed by these distant peaks and ridges, and the air has a bluish tint to it because of the chemicals emitted from the eucalyptus trees, known as terpenes. They scatter light in a way that gives you sort of a blue tint. But all we saw was brown smoke. You know, the fact is that you really can't get away from the impacts of climate change now. They are so profound that you see them wherever you go. And nowhere is that more true right now, of course, than the place that I've chosen to do my sabbatical, here in southeastern Australia.

CURWOOD: Jenni Doering, who's part of the team here at Living on Earth, just before we spoke to you, she showed me this map of Australia and the bushfires superimposed on the United States. And it's as if we have fires running all the way up from like Florida, Georgia into the middle of the eastern part of the country. And then another slash kind of up from St. Louis to Chicago and then up the West Coast. I mean, this is massive there.

MANN: Yeah, the scale of this is just, it's mind boggling. I've seen that same map. And it really gives you a sense of how widespread and pervasive these wildfires are. And it's really a wake up call to the rest of us. It's Australia now, but this is sort of a picture of what our future will look like if we don't act on climate. Australia is located sort of in the worst possible place on Earth if you're worried about bush fires and wildfires. It's centered right in the subtropics where there's dry, descending air and high pressure. And so you already tend to get those very hot, dry conditions in the summer. And climate change is sort of adding fuel to the fire. It's creating a perfect storm, if you will, of conditions that favor these unprecedented wildfires. But make no mistake, this is a picture, this is a portrait of, of our future, of what we'll see much more of in the United States and elsewhere around the world if we continue on the course that we're on.

Australia’s Blue Mountains are so named because gases called terpenes, which are emitted by the trees there, give distant features a distinct blue tint. But bushfires in southeast Australia turn the mountains and the sky into a brown haze. (Photo: Tatters, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So as a climate scientist, Michael Mann, how do you explain the connection between climate change, climate disruption and the Australian wildfires?

MANN: Yeah, what I tell people is, you know, it's not rocket science. It's pretty basic. You take unprecedented heat and unprecedented drought, both of which southeastern Australia is experiencing right now. You put them together, you get wildfires. You get these bushfires that are greater in extent and intensity and faster spreading, because of the warmer conditions and the dry conditions, which means there's more fuel around, more dead shrubbery and trees and material that provides, essentially, the kindling for these fires. There was a report, a climate assessment report, conducted in Australia back in, I think it was 2007 or so, where their scientists made a prediction, they said, by 2020, if we continue to warm the planet by emitting carbon into the atmosphere, by 2020, we will see a notable uptick in bushfires in southeast Australia. And guess what? It's 2020. We're a week into it. And so they predicted it pretty much right on the dot. And this is something that we saw coming. Our projections decades ago said the continents of the world will get warmer and drier in the summer in subtropical regions like Australia or California. And we'll see far more widespread and devastating wildfires. And guess what we're seeing from California in 2019. And guess what we're seeing in Australia in 2020. We're seeing epic wildfires much as we predicted.

The smoke is so thick in Katoomba tourists are opting for photos with billboards, rather than the Three Sisters themselves. @abcsydney pic.twitter.com/MOWvH8UBgs

— Tom Lowrey (@tomlowrey) December 30, 2019

CURWOOD: Don't you wish you were wrong?

MANN: Yeah, that's the sad thing about being a climate scientist. In fact, the great Sherwood Rowland, who's a Nobel Prize winner for his work on ozone depletion, once said, you know, what good is doing this science, only to watch our predictions come true? And that's the sad reality, that the validation of our science also speaks to our failure as a civilization to take what science has to say and to actualize it in terms of policy to act on this crisis.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann, you recently published an op-ed in The Guardian, linking the Australian fires to climate disruption and discussing the Australian government's lack of action on climate. Who were you most hoping to reach with that opinion piece?

A wildlife rescuer holds a koala saved from the raging bush fires in Australia.

— ABC News (@ABC) January 7, 2020

The University of Sydney has estimated 480 million animals have perished in the fires in New South Wales alone. https://t.co/BFXpWpSiiq pic.twitter.com/NrTM32DEeg

MANN: Well, really the people of Australia. They get it, they understand that they have a problem, and they're increasingly frustrated with their leadership, with the Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, who was vacationing in Hawaii with his family; as Australia was suffering through these deadly unprecedented wildfires and extreme heat, he was off in Hawaii vacationing. His government played a destructive role in the Madrid climate meeting a couple weeks ago, where they basically threw a monkey wrench into the works by arguing that Australia shouldn't have to meet the commitments that it's being asked to make in terms of reducing its carbon emissions. And Scott Morrison's government has doubled down on coal. They have green-lighted the Adani coal mine, this huge prospective coal mine, that if it goes ahead, it will double Australia's carbon emissions from coal burning. Now, keep in mind that Australia is one of the largest exporters of coal, so you have to look just not at how much fossil fuels they are burning themselves, but how much of this coal they're shipping off to China and elsewhere, that is being burned and is loading our atmosphere with carbon. And so, Australia, at a time when they need to be joining the rest of the world and dramatically bringing down their carbon emissions, is actually increasing their carbon emissions. And their government is increasingly out of step with their people, the people are calling for action. And so part of my message is to the people of Australia to tell them, look, you need leadership that is going to represent you rather than a few large fossil fuel interests. And the only way to make that happen, of course, is to turn out and vote, and vote for politicians who will represent your interests rather than the special interests.

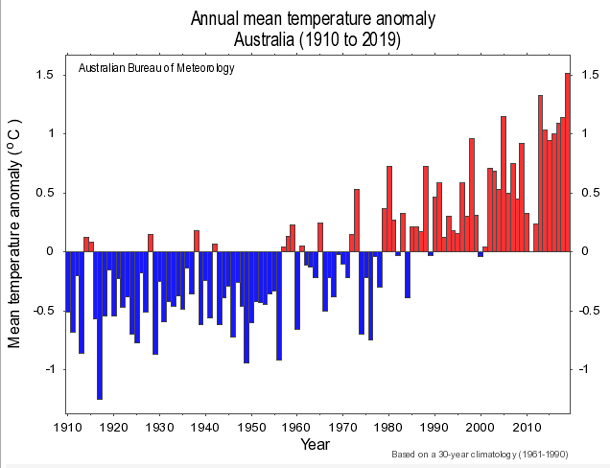

CURWOOD: So Michael, it's barely 2020. And the global average temperature is up a little more than a degree centigrade. And yet, we're already seeing these extreme conditions. So in a place like Australia, how much hotter and more fire prone could things get 'down under' in this next decade and beyond?

The annual mean temperature in Australia has been inching upwards over the last century, increasing conditions for more frequent and more intense bushfires. (Image: Bureau of Meteorology, Australian Government, climate tracker tool)

MANN: Well, it's scary to think about that. Because even if we can stabilize global temperatures now, even if we could bring our carbon emissions down dramatically over the next decade, which is what's necessary if we're going to avert catastrophic warming of the planet -- a degree and a half Celsius, a little less than three degrees Fahrenheit warming of the planet, where we really start to see the very worst impacts of climate change globally. To avert that we have to bring our carbon emissions down by a factor of two over the next decade. Even if we're able to do that, Australia will exist in this state of elevated wildfire danger, they will be dealing with a new normal, if you will. The sorts of summers that we're seeing now, this summer, and what's playing out with the heat and the drought and the widespread bushfires, that will remain commonplace. That's the best case scenario. People often say, well, are we dealing with, you know, is this a new normal that we have to deal with? The new normal is the best case scenario. That's the scenario where we rapidly bring down our carbon emissions. And we find a way to adapt to these new conditions that we have to deal with. The worst case scenario is, of course, that this is just an ever upward-sliding baseline, that Australia gets warmer and drier, and the wildfires become more intense and more widespread and more frequent. So we still have a choice to make. The choice is between avoiding the additional warming of the planet that we can by taking dramatic action and finding a way to adapt to these new conditions on the ground that we need to deal with, or failing to act and watching places like Australia essentially become uninhabitable to human beings.

CURWOOD: Now, as the planet has warmed, we've seen really horrific climate-related weather events in a number of places, or sea level rise -- the Bay of Bengal, what's going on in Indonesia right now; horrific storms off of Mozambique. But Australia is an English-speaking, very white, Western economically-focused country that gets a lot of visibility in the media. To what extent do you think that this fire catastrophe in Australia is waking up the industrialized world that's not paid as much attention to these problems in the less developed world?

There’s a koala detection dog in NSW, Australia called bear that’s working with all the firefighters here and it’s helping find all the koala bears in the places where the fires are. Look at his little boots!! #NSWfires pic.twitter.com/UK3Txf8rFq

— Connor McLaughlin (@_ConnorM) January 5, 2020

MANN: Yeah, it's a great point, Steve. And I think that's, sadly, that's right. I think it's really unfortunate that we're so quick to simply ignore, in a sense, the similar tragedies that have unfolded before in places like Puerto Rico, in the wake of the catastrophic Hurricane Maria landfall, where they lost fresh water and electricity for months, and the scenes that we saw coming out of there looked almost post-apocalyptic and thousands of people perished directly or indirectly as a result of that hurricane impact. And make no mistake, we would not have seen such a destructive hurricane in the absence of the warming of the planet. And so we saw that devastation play out. And yet to some extent it was dismissed by our president, and it was dismissed by some Americans because, frankly, these people, well, they're brown, they're not white. It's sad that there still is that intrinsic racism and it makes it easy for some to dismiss the tragedies that are unfolding in the third world and the less developed regions of the world, who are seeing the worst impacts of climate change, in part because they have the least resilience, the least wealth, the least infrastructure to insulate themselves from those impacts.

CURWOOD: To what extent does Australia illustrate that it doesn't matter how rich you are, you're going to have a problem with the climate?

MANN: Yeah, that's, that's exactly right. You know, at some point, climate change becomes uninsurable. There's no amount of money that we can produce that can restore a rainforest that's been burned to the ground, that can restore a population of koalas that have been decimated, that can restore the lives of people who have perished in house fires arising from these bushfires. There's no amount of money that can restore the beauty and wonder of the Great Barrier Reef. And people, to some extent, don't quite get that. Sometimes we don't appreciate a thing until it's gone. And I fear that to some extent, that's what's going to have to happen here, we're going to actually have to see some of the things that we hold dear and precious, disappear off the face of the earth until some people get it, that this is an existential crisis.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann is a distinguished professor of atmospheric science at Penn State University and currently on sabbatical at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. Michael Mann, thanks so much for taking the time with us.

MANN: Thank you, Steve. Always a pleasure.

Links

BBC | “How did Australia fires start and what’s being done”

Vox | “A staggering 1 billion animals are now estimated dead in Australia’s fires”

NYTimes | “How Rupert Murdoch Is Influencing Australia’s Bushfire Debate”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth