January 10, 2020

Air Date: January 10, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Australia's Wildfires Point to the Future

View the page for this story

Australia is in the throes of its worst fire season in modern history. As thousands of homes are incinerated and an estimated billion animals perish, the world is getting a glimpse of our future in a warming world. Penn State University climatologist Michael Mann joins Host Steve Curwood from Sydney, where he is taking a sabbatical to study the influence of climate change on extreme weather events. Prof. Mann explains the clear link between climate disruption and wildfire disasters, and discusses Aussies’ frustration with the response of their government to the climate crisis. (13:48)

Climate Disasters Drive Refugee Crisis

View the page for this story

2019 was a year of climate-related disasters in the developed and developing worlds alike. More people than ever are being forced from their homes because of climate-linked cyclones, sea level rise, and extreme drought, yet the United Nations has not established special legal protections for those displaced by climate disasters. Jesse Young, the Environmental Policy Lead at Oxfam America, joined Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb to talk about the most vulnerable populations and the responsibility that rich nations have to help low-income countries cope. (09:11)

McSweeney’s ‘2040 AD’ Climate Fiction Issue

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

To convey the climate crisis in a more accessible way, the literary publication McSweeney’s teamed up with the Natural Resources Defense Council for a “climate fiction” issue. “2040 AD” brings together several short stories including “The Night Drinker” by Luis Alberto Urrea. The American-Mexican author joins Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to discuss climate refugees, the innovative spirit of Mexico City, and how literature can advance awareness of the climate emergency (09:35)

Note on Emerging Science: Deep-Sea Serpents

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

Sea snakes have been spotted diving 800 feet deep - almost twice the depth of the previous seen dives. Living on Earth's Don Lyman shares more on these record-setting sea serpents. (01:27)

Beyond the Headlines: The Year in Review

View the page for this story

Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss some of the big environmental trends from the past year, from species loss and ocean health to more uplifting news concerning wind power adoption. The pair also take a look forward to a new decade and discuss what responses we might see to climate change from global governments. Finally, they conclude with a discussion of the 65th anniversary of US President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s announcement of the interstate highway system project, and consider how a new Trump administration change to the National Environmental Policy Act might affect future infrastructure construction. (06:31)

Climate and the 2019 Lexicon

/ Aynsley O'NeillView the page for this story

As a new year begins some dictionary publishers select a word or phrase that represents the passing year above all others, their 'Word of the Year'. Three prominent dictionaries have selected words of the year for 2019 relating to climate and the environment. Living on Earth's Aynsley O'Neill has more on these words and what they say about these times. (04:18)

BirdNote®: Encounter with a Cassowary

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

BIRDNOTE®: ENCOUNTER WITH A CASSOWARY: BirdNote's Mary McCann describes an interaction with a Southern Cassowary, a huge, flightless, and almost-prehistoric looking bird. Found in the forests of Northern Australia, it has the lowest-pitched birdcall in the world. (02:04)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUEST: Michael Mann, Luis Alberto Urrea, Jesse Young

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman, Mary McCann, Aynsley O’Neill

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

The Australian bushfires are on a scale never before seen but scientists tell us they are likely to get much worse.

MANN: People often say, well, are we dealing with, is this a new normal that we have to deal with? A new normal is the best case scenario. That's the scenario where we rapidly bring down our carbon emissions and we find a way to adapt to these new conditions that we have to deal with.

CURWOOD: Also, climate related disasters like floods, wildfires, and hurricanes are forcing millions of people from their homes, three times more than war and conflict.

YOUNG: In our study you can see that 87% of people around the world who’ve been displaced by disasters are being driven by weather events. So, this is the overwhelming driver forcing people to leave their homes and the places they grew up.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Australia's Wildfires Point to the Future

The 2019-2020 fires in Australia have burned through about a third of Kangaroo Island, a haven for rare wildlife. (Photo: robdownunder, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The land ‘down under’ has turned into a hellscape in recent weeks. Thousands have fled massive fires driven by years of drought and extreme heat on Australia’s south-east coast. ABC reporter Maggie Rulli was on the ground in the midst of the fires.

RULLI: Tonight, the dire warnings from Australia’s prime minister. The worst fire disaster in the country’s history could go on for months. Apocalyptic scenes, the infernos now forcing the largest peace time evacuation ever. The winds here just keep picking up it is fueling these flames. You can feel the smoke stinging your eyes. You can feel that heat off the fire. It is radiating right now. It is absolutely incinerating all of this brush all of these trees. Many of these are going to go at any second.

CURWOOD: Climate scientists say there is a clear link between climate change and the extreme drought and heat conditions that are helping to fuel the deadly fires. For more, we’re joined now by Michael Mann, a professor of atmospheric science at Penn State who just started a sabbatical in Sydney to study the linkages between climate change and extreme weather events. Hey Michael, welcome back to Living on Earth, and we’ve reached you in Sydney, is that right?

MANN: Yes, I'm in fact in Coogee Beach, just south of Sydney, looking out over the Pacific Ocean as I talk to you.

A burned-out Australian forest after a bushfire (Photo: Elizabeth Donoghue, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And you're there on a sabbatical, Professor Mann, but a bit of a busman's holiday. I mean, as a climate scientist, you are going to part of the universe that's really seeing some of the more devastating effects of drought and climate disruption, huh?

MANN: Well, that's right. Ironically, because the research agenda was determined well over a year ago, I'm here to study the impacts of climate change on extreme weather events in Australia. And it turns out that my sabbatical now coincides with perhaps the most profound episode of extreme weather that Australia has ever seen. When I arrived, I did have an opportunity to do a little bit of vacationing with my family. We went up to see the Great Barrier Reef while we still can, because of course it is threatened by bleaching from warming ocean waters and ocean acidification. And then we went to see another one of Australia's great wonders, the Blue Mountains, which are these vast expanses of temperate rainforest that are framed by these distant peaks and ridges, and the air has a bluish tint to it because of the chemicals emitted from the eucalyptus trees, known as terpenes. They scatter light in a way that gives you sort of a blue tint. But all we saw was brown smoke. You know, the fact is that you really can't get away from the impacts of climate change now. They are so profound that you see them wherever you go. And nowhere is that more true right now, of course, than the place that I've chosen to do my sabbatical, here in southeastern Australia.

CURWOOD: Jenni Doering, who's part of the team here at Living on Earth, just before we spoke to you, she showed me this map of Australia and the bushfires superimposed on the United States. And it's as if we have fires running all the way up from like Florida, Georgia into the middle of the eastern part of the country. And then another slash kind of up from St. Louis to Chicago and then up the West Coast. I mean, this is massive there.

MANN: Yeah, the scale of this is just, it's mind boggling. I've seen that same map. And it really gives you a sense of how widespread and pervasive these wildfires are. And it's really a wake up call to the rest of us. It's Australia now, but this is sort of a picture of what our future will look like if we don't act on climate. Australia is located sort of in the worst possible place on Earth if you're worried about bush fires and wildfires. It's centered right in the subtropics where there's dry, descending air and high pressure. And so you already tend to get those very hot, dry conditions in the summer. And climate change is sort of adding fuel to the fire. It's creating a perfect storm, if you will, of conditions that favor these unprecedented wildfires. But make no mistake, this is a picture, this is a portrait of, of our future, of what we'll see much more of in the United States and elsewhere around the world if we continue on the course that we're on.

Australia’s Blue Mountains are so named because gases called terpenes, which are emitted by the trees there, give distant features a distinct blue tint. But bushfires in southeast Australia turn the mountains and the sky into a brown haze. (Photo: Tatters, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So as a climate scientist, Michael Mann, how do you explain the connection between climate change, climate disruption and the Australian wildfires?

MANN: Yeah, what I tell people is, you know, it's not rocket science. It's pretty basic. You take unprecedented heat and unprecedented drought, both of which southeastern Australia is experiencing right now. You put them together, you get wildfires. You get these bushfires that are greater in extent and intensity and faster spreading, because of the warmer conditions and the dry conditions, which means there's more fuel around, more dead shrubbery and trees and material that provides, essentially, the kindling for these fires. There was a report, a climate assessment report, conducted in Australia back in, I think it was 2007 or so, where their scientists made a prediction, they said, by 2020, if we continue to warm the planet by emitting carbon into the atmosphere, by 2020, we will see a notable uptick in bushfires in southeast Australia. And guess what? It's 2020. We're a week into it. And so they predicted it pretty much right on the dot. And this is something that we saw coming. Our projections decades ago said the continents of the world will get warmer and drier in the summer in subtropical regions like Australia or California. And we'll see far more widespread and devastating wildfires. And guess what we're seeing from California in 2019. And guess what we're seeing in Australia in 2020. We're seeing epic wildfires much as we predicted.

The smoke is so thick in Katoomba tourists are opting for photos with billboards, rather than the Three Sisters themselves. @abcsydney pic.twitter.com/MOWvH8UBgs

— Tom Lowrey (@tomlowrey) December 30, 2019

CURWOOD: Don't you wish you were wrong?

MANN: Yeah, that's the sad thing about being a climate scientist. In fact, the great Sherwood Rowland, who's a Nobel Prize winner for his work on ozone depletion, once said, you know, what good is doing this science, only to watch our predictions come true? And that's the sad reality, that the validation of our science also speaks to our failure as a civilization to take what science has to say and to actualize it in terms of policy to act on this crisis.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann, you recently published an op-ed in The Guardian, linking the Australian fires to climate disruption and discussing the Australian government's lack of action on climate. Who were you most hoping to reach with that opinion piece?

A wildlife rescuer holds a koala saved from the raging bush fires in Australia.

— ABC News (@ABC) January 7, 2020

The University of Sydney has estimated 480 million animals have perished in the fires in New South Wales alone. https://t.co/BFXpWpSiiq pic.twitter.com/NrTM32DEeg

MANN: Well, really the people of Australia. They get it, they understand that they have a problem, and they're increasingly frustrated with their leadership, with the Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, who was vacationing in Hawaii with his family; as Australia was suffering through these deadly unprecedented wildfires and extreme heat, he was off in Hawaii vacationing. His government played a destructive role in the Madrid climate meeting a couple weeks ago, where they basically threw a monkey wrench into the works by arguing that Australia shouldn't have to meet the commitments that it's being asked to make in terms of reducing its carbon emissions. And Scott Morrison's government has doubled down on coal. They have green-lighted the Adani coal mine, this huge prospective coal mine, that if it goes ahead, it will double Australia's carbon emissions from coal burning. Now, keep in mind that Australia is one of the largest exporters of coal, so you have to look just not at how much fossil fuels they are burning themselves, but how much of this coal they're shipping off to China and elsewhere, that is being burned and is loading our atmosphere with carbon. And so, Australia, at a time when they need to be joining the rest of the world and dramatically bringing down their carbon emissions, is actually increasing their carbon emissions. And their government is increasingly out of step with their people, the people are calling for action. And so part of my message is to the people of Australia to tell them, look, you need leadership that is going to represent you rather than a few large fossil fuel interests. And the only way to make that happen, of course, is to turn out and vote, and vote for politicians who will represent your interests rather than the special interests.

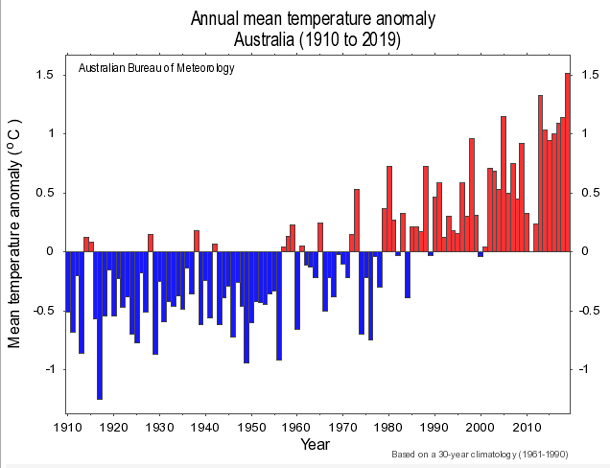

CURWOOD: So Michael, it's barely 2020. And the global average temperature is up a little more than a degree centigrade. And yet, we're already seeing these extreme conditions. So in a place like Australia, how much hotter and more fire prone could things get 'down under' in this next decade and beyond?

The annual mean temperature in Australia has been inching upwards over the last century, increasing conditions for more frequent and more intense bushfires. (Image: Bureau of Meteorology, Australian Government, climate tracker tool)

MANN: Well, it's scary to think about that. Because even if we can stabilize global temperatures now, even if we could bring our carbon emissions down dramatically over the next decade, which is what's necessary if we're going to avert catastrophic warming of the planet -- a degree and a half Celsius, a little less than three degrees Fahrenheit warming of the planet, where we really start to see the very worst impacts of climate change globally. To avert that we have to bring our carbon emissions down by a factor of two over the next decade. Even if we're able to do that, Australia will exist in this state of elevated wildfire danger, they will be dealing with a new normal, if you will. The sorts of summers that we're seeing now, this summer, and what's playing out with the heat and the drought and the widespread bushfires, that will remain commonplace. That's the best case scenario. People often say, well, are we dealing with, you know, is this a new normal that we have to deal with? The new normal is the best case scenario. That's the scenario where we rapidly bring down our carbon emissions. And we find a way to adapt to these new conditions that we have to deal with. The worst case scenario is, of course, that this is just an ever upward-sliding baseline, that Australia gets warmer and drier, and the wildfires become more intense and more widespread and more frequent. So we still have a choice to make. The choice is between avoiding the additional warming of the planet that we can by taking dramatic action and finding a way to adapt to these new conditions on the ground that we need to deal with, or failing to act and watching places like Australia essentially become uninhabitable to human beings.

CURWOOD: Now, as the planet has warmed, we've seen really horrific climate-related weather events in a number of places, or sea level rise -- the Bay of Bengal, what's going on in Indonesia right now; horrific storms off of Mozambique. But Australia is an English-speaking, very white, Western economically-focused country that gets a lot of visibility in the media. To what extent do you think that this fire catastrophe in Australia is waking up the industrialized world that's not paid as much attention to these problems in the less developed world?

There’s a koala detection dog in NSW, Australia called bear that’s working with all the firefighters here and it’s helping find all the koala bears in the places where the fires are. Look at his little boots!! #NSWfires pic.twitter.com/UK3Txf8rFq

— Connor McLaughlin (@_ConnorM) January 5, 2020

MANN: Yeah, it's a great point, Steve. And I think that's, sadly, that's right. I think it's really unfortunate that we're so quick to simply ignore, in a sense, the similar tragedies that have unfolded before in places like Puerto Rico, in the wake of the catastrophic Hurricane Maria landfall, where they lost fresh water and electricity for months, and the scenes that we saw coming out of there looked almost post-apocalyptic and thousands of people perished directly or indirectly as a result of that hurricane impact. And make no mistake, we would not have seen such a destructive hurricane in the absence of the warming of the planet. And so we saw that devastation play out. And yet to some extent it was dismissed by our president, and it was dismissed by some Americans because, frankly, these people, well, they're brown, they're not white. It's sad that there still is that intrinsic racism and it makes it easy for some to dismiss the tragedies that are unfolding in the third world and the less developed regions of the world, who are seeing the worst impacts of climate change, in part because they have the least resilience, the least wealth, the least infrastructure to insulate themselves from those impacts.

CURWOOD: To what extent does Australia illustrate that it doesn't matter how rich you are, you're going to have a problem with the climate?

MANN: Yeah, that's, that's exactly right. You know, at some point, climate change becomes uninsurable. There's no amount of money that we can produce that can restore a rainforest that's been burned to the ground, that can restore a population of koalas that have been decimated, that can restore the lives of people who have perished in house fires arising from these bushfires. There's no amount of money that can restore the beauty and wonder of the Great Barrier Reef. And people, to some extent, don't quite get that. Sometimes we don't appreciate a thing until it's gone. And I fear that to some extent, that's what's going to have to happen here, we're going to actually have to see some of the things that we hold dear and precious, disappear off the face of the earth until some people get it, that this is an existential crisis.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann is a distinguished professor of atmospheric science at Penn State University and currently on sabbatical at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. Michael Mann, thanks so much for taking the time with us.

MANN: Thank you, Steve. Always a pleasure.

Related links:

- Michael Mann’s opinion piece in The Guardian | “Australia, your country is burning – dangerous climate change is here with you now”

- BBC | “How did Australia fires start and what’s being done”

- Vox | “A staggering 1 billion animals are now estimated dead in Australia’s fires”

- The Independent opinion | “Where were the celebrity pledges when the climate emergency hit Malawi? This crisis can’t be solved by handouts”

- NYTimes | “How Rupert Murdoch Is Influencing Australia’s Bushfire Debate”

- CNN | “Australia’s Kangaroo Island is a haven for rare wildlife. A third of it has burned in bushfires, NASA images show”

[MUSIC: Ticki Stamasuri, “Trance”]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Using fiction to tell the hard truths of climate change. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Emancipator “Canopy”]

Climate Disasters Drive Refugee Crisis

36 year old Hoden Abdi Iwal walks with six of her children to collect water in Gilo, Ethiopia. The ongoing drought has caused the family to lose their crops and livestock, making it very difficult for the family to survive. The Horn of Africa continues to face devastating droughts, causing alarming food security conditions for millions of people in the region. (Photo: Pablo Tosco, Oxfam International)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

2019 was a year of climate-related disasters, from flashfloods in the Midwestern US to wildfires in California and Australia. And tropical cyclones killed thousands of people in southern Africa and the Philippines. Scientists forecast more extreme weather events in our warming world, potentially displacing hundreds of millions of people worldwide. But climate change refugees are not recognized by international law and the United Nations doesn’t offer them any additional protections. But people are 3 times more likely to be displaced by climate related disasters than by conflict or war, which does allow victims to claim refugee status. Some 20 million people are displaced from their homes each year as a result of climate disruption and those in small island developing states are among the most vulnerable where now every year rising waters force roughly 5 percent of them to abandon their homes. In December at COP 25 in Madrid, Omar Figueroa, environment minister for Belize, spoke to the conference. He was representing low-lying and small island states.

FIGUEROA: Countries such as Tuvalu and Kiribati are literally at risk of disappearing because of sea level rise. Loss and damage is not an idea that is floating. Visit any of our sister islands and you will see and feel what we are talking about.

CURWOOD: Indeed, residents of Kiribati say they are struggling to survive on the island and must face the difficult decision to leave.

WOMAN 1: I have no choice. No other choice, if tsunami coming or high tides affecting our water, how can we survive for the future?

WOMAN 2: The most disastrous thing in Kiribati right now is the rising of the sea. If you look around you now you see sea walls. The tide just keep on coming and taking away our lands.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb asked Jesse Young, the policy lead in climate change at Oxfam America about where most climate refugees are coming from.

BASCOMB: Where are the hotbeds for refugees being displaced because of climate?

YOUNG: A lot of them come in Asia and that's obviously because 60% of the world's population lives in Asia. You also have a lot of mega cities in urban centers in Asia tend to be located in coastal areas, low lying coastal areas that are most vulnerable to storm surge and cyclones and floods. It also tends to be where a lot of the world's most extreme poverty is. So if you combine a growing incidence of extreme weather with concentrated poverty and large groups of people, you get a result like this.

A mother and her son walk far distances to collect firewood in Somalia. Her family has been displaced since the country’s 2017 drought, losing all of their livestock. Somalia remains on the edge of a humanitarian catastrophe as continuing drought means very little recovery and resilience for millions of Somalis who have lost their livelihoods to adequate food and water sources. (Photo: Vincent Best, Oxfam International)

BASCOMB: Are they ending up in refugee camps or in cities and how is that working out for them?

YOUNG: Depending on where you are usually you will be displaced within your country. We refer to these people as internally displaced persons. These are people who've been forced to leave their homes but stay within the borders of the country that they reside in. In smaller countries or in regions bordering other nations, you have people fleeing across borders into other countries. Some people do end up in refugee camps. More often people just end up fleeing into cities, especially if they're fleeing rural areas or dealing with a loss of arable land, they just end up as displaced people ringing larger cities.

BASCOMB: And are they finding jobs there? I mean, I imagine if you have a massive influx of people into cities, it must be a real burden to those cities that probably aren't prepared for it.

YOUNG: We know that when people are displaced because of climate change, they are usually economically marginalized. If they have children, their children have a tougher time finding an education and people who are displaced due to climate change, have a much higher likelihood of falling into intergenerational cycles of poverty, obviously, because they've lost their social capital, their homes, their belongings, their accumulated wealth, If they had it to begin with.

BASCOMB: And what about the social burdens of moving and being displaced from your homes?

YOUNG: It can be really severe; women are more vulnerable when they're displaced due to climate change. While women constitute 43% of smallholder farmers, they're typically more responsible for being caregivers for children and the sick and the elderly, they're more responsible, generally speaking, for finding food for their families. So when they are displaced, they have less ability to do all of those things. They're also much more vulnerable to sexual exploitation and abuse as are their children. So it's a profound social dislocation, even in environments where countries have tried to take populations and preemptively relocate them. It's really tough to reintegrate people. People who’ve built social bonds, they know their community and sort of pulling them out and putting them somewhere new is really difficult to adapt to, as you were, I can probably imagine.

An Ethiopian farmer grazes flocks of animals. Droughts in Ethiopia have been at their peak high since 2008. (Photo: Kieran Doherty, Oxfam International)

BASCOMB: Yeah, yeah, exactly. Well, we did a story last year that made the case that a lot of migrants turning up on our southern border from Central America could be considered climate refugees. You know, they're dealing with drought and the collapse of subsistence agriculture there. Is that something you guys looked into?

YOUNG: Yeah, Oxfam America has done a lot of work on folks fleeing the dry corridor countries. Obviously, there's an enormous amount of deprivation in that region, in Guatemala in 2019 alone, 78% of the corn and bean harvest was lost. There have been droughts of historic length due to an extended El Nin ̃o cycle in that part of the world. So people are fleeing their homes due to crime, loss of livelihoods, loss of foods. It's a complex mix of factors obviously. It's difficult to determine any one case if there's one specific reason why someone leaves their home. But I think it's fair to say that there's a profound climate dimension of why people are fleeing their homes in El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua.

Angelica stands next to her home after it was destroyed by last year’s Cyclone Idai in Mozambique. (Photo: Christian Jepsen, EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: And we talked about Asia. What about the parts of Africa are you seeing this problem manifests there?

YOUNG: One of the hotspots is actually the Horn of Africa. So this is far East Africa, Ethiopia, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan. Saw 3.8 million people displaced by conflict and a million people displaced by extreme weather disasters in 2018. There's been a series of intense droughts in that part of the world. So this is, as is often the case, just exacerbating existing civil wars and violence and just making the displacement effect all that more worse, more and more people being forced to flee their homes, because of the drought.

BASCOMB: What about developing countries like Bangladesh, for example, that are just, you know, synonymous with sea level rise and flooding? I mean, to what degree is the government there able to address this problem for the people and what level of responsibility should they have?

A father carries his son across a broken bamboo bridge on the edge of Balhukai camp, Bangladesh. The 2019, South Asia experienced some of the worst floods in years, forcing millions of people from their homes and threatening their lives. (Photo: Aurrelie Marrier, Oxfam International)

YOUNG: One of the great inequities of climate change is while it infects the entire planet, it does not affect everyone equally, most of these countries had very little to do with putting the emissions in the atmosphere that are changing the climate. That said they're the ones to feel the brunt of it and the most severe impacts. Of course, I think it's important to point out that people aren't just being acted on by climate change in the poor in developing world. They have agency, they’re responding in this on their own and their governments are doing their best to adapt. This is not a question of just helplessness on their part. Bangladesh has actually done a whole lot to adapt to climate change and trying to better protect its citizens. There was a cyclone in 2018 that displaced a huge amount of people in Bangladesh, but most of those people were preemptively evacuated, meaning the government came along and said we know this is coming you have to leave your homes now, far fewer people will die and be injured as a result. So they are adapting, they're putting new laws in place, they're working with international donors to make sure that their populations are less vulnerable. But there's only so much you can ask a very, very poor country to do without additional resources on their own.

BASCOMB: Well, that begs the question, who should be held responsible for the displacement and helping people resettle?

YOUNG: It's hard to argue against the notion that developed countries bear most of the burden here and should be most responsible for generating the resources to help countries transition. We have to keep in mind the climate is a really durable system and the pollution we put there persists for decades to come. And it's a question of adapting and being more resilient to that. But we need to make sure the countries that are feeling those impacts now have the financial resources and the technical resources to meet that challenge and by no one's measure are financial flows from the developed world significant enough to meet that. The total amount of funding flowing from developed countries for climate change is still much, much smaller than it needs to be from both public and private sources.

Jesse Young is the Climate Policy Lead at Oxfam America. (Photo: Oxfam America)

BASCOMB: Well, now looking ahead to 2020 what are you hoping to see this year that could improve the situation for the world's refugees?

YOUNG: Two big picture things. One, we have this big international climate agreement called the Paris Agreement and we are looking for countries to really step up their climate pledges. The way Paris works is countries come to the table with what they believe they can do to reduce emissions. We need countries to do far more and especially the big developed and developing countries. You know, this is the Australias, the Indias, the Chinas, the EU need to do a lot more than they are right now to reduce emissions, especially for a country like the United States it's presently withdrawing from the Paris Agreement. The second thing is countries need to step forward with more financial resources. As I was saying earlier, a lot of this stuff is baked into the climate system already and countries need help. They need financial help to relocate people protect people make their economies more climate proof. Because right now, we just don't have enough resources in the system to adequately care for the millions of people being affected by climate change. So more climate ambition and more money, basically.

CURWOOD: Jesse Young is the Policy Lead in Climate Change at Oxfam America, speaking with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

Related links:

- Click here for OXFAM International’s study on climate-fueled displacement

- Click here to read the Alliance of Small Island States’ Closing Statement for COP25

- The UN Refugee Agency | Climate Change and Displacement

[MUSIC: Keola Beamer, “Dancers in the Land of Po” on Wooden Boat, by Keola Beamer, Dancing Cat]

McSweeney’s ‘2040 AD’ Climate Fiction Issue

2040 AD spans genres, continents, and iterations of disaster. (Photo: Fabiola Nunez, NRDC)

CURWOOD: To convey the climate crisis in a more accessible way the literary publication McSweeney’s decided to team up with the Natural Resources Defense Council on a “climate fiction” issue, called 2040 AD. They called on short story authors to envision what the world might be like in twenty years if global temperatures continue to rise. Many of the McSweeney stories paint a grim picture, with democracies collapsing and people left to fend for themselves as resources dwindle. These fictional stories from the future are placed all over the world, from Istanbul to Singapore to Mexico City. And that’s where Luis Alberto Urrea sets his story, “The Night Drinker”, which imagines a dangerously warming world colliding with ancient culture and tradition. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering spoke with Luis Alberto Urrea.

URREA: You know, the genius of it was to pair each of us with essentially a climate scientist who could make sure that we weren't going too far afield in what we were saying and they provided reams of data and interesting information. The hope in it for all of us, I think, is this finding out that it's a, it's a kind of a two- way street. That hard science and the beauty of it and the indisputable hard facts of it could bolster the a little more nebulous and very disputable feelings of what we write, you know, that a fact-based response to what's in fact happening to the world, I think empowered both sides in a really wonderful way.

Author Luis Alberto Urrea reads from his story "The Night Drinker" at the 2040 A.D. release event in Chicago, Dec. 2, 2019. (Photo: courtesy of Fabiola Nunez / NRDC)

DOERING: There's a passage in your story, The Night Drinker, that describes the technological adaptation that goes on in Mexico City. Could you please read us this passage? I think it's on page 52. And it starts with "these aguaceros."

URREA [READING]: These aguaceros, as we called the drenching rains, were fodder for our computer analyses. And by 2035, the government and the scientists of UNAM assaulted our thirst with Proyecto Tlaloc, perhaps the largest drought amelioration project in history. I was there to see it. I was Tlaloc's contracted historian. Rain seemed at first a further punishing apocalypse. Yes, it flooded us. Yes, it brought down mudslides and avalanches. Yes, the refugees and the poor suffered the most, though we all suffered. But we soon saw it was a reprieve if we had the will to take creative action. The kilometers of standing buildings were perfect water collecting sites, like the solar panel and wind turbine platforms they had become, we repurposed them. We created vast networks of flumes and reservoirs to slake our valleys' thirst; the army, the Red Cross, and hordes of volunteers -- many of them, it pains me to say, gringos -- evolved instantly into a disorganized but miraculous bureaucracy of hope.

DOERING: Thank you. So one, one aspect of your story that was kind of surprising maybe to me, it feels hopeful and, and rich and colorful in a way that all these people are coming together even if they are refugees. Mexico City is already a very diverse city. But, even more diverse, culturally. And I wonder if you can just talk a little bit about that, and how you imagine the city, you know, being able to accommodate different groups of people in a way, it sounds like in a kind of a unique way compared to some other, you know, cities around the globe that aren't Mexico City.

Ten short stories set all over the world make up the "2040 A.D." issue of McSweeney's. (Photo: courtesy of NRDC/McSweeney's)

URREA: Mexico City. Yeah, because I think you know, I think one of the brilliant things about Mexico City is it puts the lie to the easy pop culture impression of quote "Mexicans," quote "Mexico," which is a construct, let's face it. You know, there are novels coming out to this day that, talking about the faceless mass of you know, brown people in the slaughter zones and it's not necessarily that way at all. You know, to me the wonder of Mexico City is you can, you can drive from stunning skyscraper disco land, to you know, somebody's little farm with a donkey right there in the town. And Mexico is you know, is doing so much stuff or trying to. They're planting forests in Honduras for the Hondurans to try to mitigate the drought and the famine that's coming. You know, they are planting millions of trees in Mexico City to start processing carbon out of the air again. They're working on all kinds of things, smart buildings, solar, wind generating, you know, green roofs, all that stuff. So in that way, I wanted to make the case for someone from Mexico, and specifically people who are in Mexico City, who are deeply proud of, and in love with the city and consider themselves to be in the premier city of the world, much like New Yorkers do. Right? You know, people in Hong Kong do. And that's not the trope that I see in popular American culture, that Mexicans adore Mexico and are proud of Mexico and in fact, consider Mexico one of the cutting edge countries in the world.

DOERING: Can you talk a bit about how this like moment with, you know, this talk about the border wall and talk about immigration in the United States, how that sort of may have factored into your story.

URREA: You know, what's interesting to me is the tides of refugees, the alleged caravans, etc. etc., which we don't yet, I don't think, have processed that they are largely climate refugees. You know the Haitian population came in response to the hurricanes, you know, initially the big earthquakes and then the hurricanes. And, you know, they could go to Brazil, which they did. And it's, you know, if you have a sense of humor about it, if you go to Tijuana, there are whole sections in Tijuana that have Haitians, and people on the street are learning Haitian French, and some of the taco stands, are now selling Haitian food. And there's a corresponding Trumpian movement, which, to me is weirdly hilarious. They have MAGA hats in Tijuana in Spanish that say 'Make Tijuana Great Again' --

DOERING: No way.

URREA: -- Which to me or, you know, anyone from Tijuana keeps thinking, 'again?' You know, were we a great leader of the world before? But this is all this response, I think, of, of encroachment. And I think what's fascinating about this whole climate crisis is the encroachment, you know, the coming on of desertification, the coming on of massive fires, the coming on of drought, ultimately the coming on of salt water flooding. This is fascinating that there's this thing coming. It's like the, you know, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, right? What beast is coming toward us?

Luis Alberta Urrea is a 2005 Pulitzer Prize finalist for nonfiction and author of 17 books of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. (Photo: Larry D. Moore, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DOERING: Yeah, I feel like I've been hearing inklings of the need for more imagination, in thinking about climate change and more, you know, storytelling and it feels like, like now that I can picture this world that, you know this this dream is sort of like being brought to life for me through these stories. It feels like thinking about climate change is just a little different.

URREA: Well, I think climate change whatever it is, is an evolutionary moment. And I think that you know, our choices are fairly simple, we adapt or we don't. And I think the, you know, the outcome of that is pretty dire honestly. I mean, I don't want to be a, you know, Chicken Little but the chips are on the table, and we have to, we have to be realistic and deal with them. It doesn't mean you know, we're going to tell farmer John, he's terrible, shouldn't have had a pig farm, none of that stuff. Just that this is something we need to work together on as a family. My entire message has always been, there is no them, there is only us, and this entire phenomenon, to me anyway, especially the denial part, is the obsession with them. There's somebody out there, and they're going to come in here and steal my crackers. I've gotta protect them. And there's no, we're only us. There's only, there's only so much room on the rock that we're on. And honestly, especially now with genetics, you're going to find out we all are actually cousins. So what's the problem? Let's save our family. And I think that's what's in the issue. Ultimately, I think it's, it's, it didn't, I don't think it meant to be this, but I think cumulatively it's a bit of a call to arms.

CURWOOD: That’s writer Luis Alberto Urrea speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Related links:

- More about Luis Alberto Urrea and his work at his website

- More about the collaboration between NRDC and McSweeney’s

[MUSIC: Raquel Cepeda, “Berimbau” on Passion – Latin Jazz, by Baden Powell/Vinicius de Moraes, Raquel]

CURWOOD: Coming up – The 2019 word of the year and the environment. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Raquel Cepeda, “Caravan” on Passion - Latin Jazz, by Juan Tizol & Duke Ellington/Irving Mills, Raquel Cepeda Music]

Note on Emerging Science: Deep-Sea Serpents

Scientists have observed two sea snakes swimming at depths of 785 and 810 feet below the surface. (Photo: Daniel Kwok, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Just ahead, a look back at 2019 and ahead at this year with Peter Dykstra but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

LYMAN: Sea snakes are primarily known to frequent relatively shallow tropical waters, like coral reefs, in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. But new data suggest they can actually dive much deeper than previously thought. A film crew in Australia recorded footage of two sea snakes diving roughly 800 feet deep, smashing the previous known record of just 436 feet. Researchers were surprised to find the salt water serpents so deep. They were thought to swim most often depths of about 160 and 300 feet. Both snakes appeared to be the same species, it looked like they were hunting for food, poking their heads into burrows in the sand. But researchers aren’t sure what kind of fish the snakes were looking for, or how the snakes might locate their prey in the dim light of the mesopelagic or “twilight zone”, as these depths are called.

Before, the deepest that scientists had seen a sea snake dive was 435 feet. (Photo: Alex Halavais, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Researchers have known for some time that sea snakes can cope with diving sickness known as the bends, which is caused by gas bubbles forming in the blood, by using gas exchanges in their skin. But they never suspected that that ability would allow sea snakes to dive so deep. Scientists say these record setting dives raise new questions about the biology and behavior of sea snakes. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

Related link:

United Press International | “Sea Snake Spotted Making Record Dive”

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Beyond the Headlines: The Year in Review

Rosa the Sumatran Rhino from Way Kambas National Park in Sumatra, Indonesia. Sumatran Rhinos and Vaquita porpoises are some of the many species at the edge of extinction. (Photo: Willem v Strien,Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, it's time in the program that we usually take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra, he's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org, but today, we're going to look back at 2019. And ahead at 2020 with you, Peter, you're there on the line in Atlanta?

DYKSTRA: I'm here, Steve. Happy new decade.

CURWOOD: Well, thank you. So where do you want to start?

This shark scupture, constructed entirely from plastic collected from beaches, represents the more than 300 billion pounds of plastic floating in the Earth’s oceans (Photo: Smithsonian’s National Zoo, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: A decade ago, we were talking about a big concern in the oceans being that we're about to fish them dry. That's still a big concern, but it's probably well down the list of major concerns for our oceans. The past decade, we've learned a lot about ocean acidification, and the threat that it poses to shellfish particularly but to all marine life. And even in the past year in 2019 there was a huge jump in awareness about plastic pollution, not just in the oceans, but in rivers, streams and the Great Lakes. The huge amount of plastic that we consume, we throw away that ends up in our waterways and is going to be, it already is, a major, major threat.

CURWOOD: What do you have for us in the way of good news or good prognostication for us?

DYKSTRA: Actually, there's quite a bit of good news out there. We don't want to give it the short shrift. The main headline and good news is that clean energy after decades of promise, seems to have finally arrived. You've got a place like Denmark that in 2019, achieved 47% of its electric power, from wind power. Wind and solar are picking up everywhere, including in the United States, where it's becoming cost competitive, and is beginning to take over a market share that had been dominated by oil and natural gas and coal and nuclear.

CURWOOD: Now, the species situation, what's been going on and what do you see going on going forward?

DYKSTRA: Species not good news, both in the plant and animal world obscure species and what we call the charismatic megafauna. The big, cute, adorable ones. Were about to lose a few of them. Lemurs in Madagascar, Rhinos, Vaquita Porpoises in the Gulf of California, this species is down to about 30. There's been concern for years, they're bycatch in fisherman's nets. And these species are disappearing in full view, with full consciousness of all of us. And it's a tragedy.

CURWOOD: It's kind of strange to know that we could be looking at the last members of these species to exist. I think the term for them is endlings, and it feels like we're losing members of our family.

In 2019, Denmark used wind turbines to generate 47% of its electrical power. (Photo: Lloyd, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: It's not a pleasant prospect, but we can also look at other species that have recovered: animals that have come off the endangered list, animals that were very worried about that there's some good news. There are already three Northern Right Whale calves that have been spotted in the Atlantic off the east coast of the US after a couple of years of real worry about that species surviving.

CURWOOD: So, in terms of the climate, I keep hearing the 2019 is the year that we woke up to the climate crisis, getting ready for the big climate meeting in the UK 2020 to all the nations of the planet are supposed to come together with a comprehensive plan to limit the warming. What do you hear? What do you see?

DYKSTRA: Well tell that to the heads of state in the UK, in Australia, in Brazil, where climate deniers have taken office in the last few years. And of course, the White House, the US leadership of the US Senate, the leadership of some of the key cabinet agencies. Climate denial may be dead in the scientific community, but it is alive and well, not just in American politics, but in other key countries as well. Will we make progress? I think we have to make progress. The question in my mind is that awareness and political action on environmental issues often come at the price of disaster. And if it's something like the Australian wildfires, or Superstorm Sandy a few years ago, that spurs a change in environmental politics, then it's going to be a costly change indeed.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about 2020, which is the year of, let's call it a closely watched election here in the United States.

DYKSTRA: Closely watched indeed and there can't be more of a stark difference in environmental policy between Donald Trump and any of the multitude of Democratic candidates out there vying for the nomination. It's a vital choice that awaits us all. But even if politics and the impeachment are dominating news headlines, that gives some cover to the anti-regulatory purge that's still underway with the Trump administration. We're seeing key laws, like the National Environmental Policy Act, that's the law that requires environmental impact statements for big construction projects. After 50 years, NEPA is now under threat.

January 7th is the 65th anniversary of President Eisenhower’s announcement of the interstate highway system (Photo by L____ on Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And I understand you have a history item related to that for us today?

DYKSTRA: On highways. This month is the 65th anniversary of President Dwight D. Eisenhower proposing the creation of the interstate highway system. He did so on January 7 1955. And that system, of course, began a year later. And now it's how we move goods around the country, how we transport ourselves, how we roll up literally billions of miles on the road each year. And of course, looking back at it, there were two purposes for that not only for commerce and transportation, but in the era of the Cold War those highways were built for defense purposes. In case of invasion, they wanted to have a highway system to move military gear around.

CURWOOD: They didn't anticipate that they would become parking lots though. Which is where I see many of the interstates these days, it feels like.

DYKSTRA: In big cities, that's certainly the case. And, we still have that other big challenge of looking at how we transport ourselves. We're addicted to fossil fuels, when will the day come when that begins to change?

CURWOOD: Good question. Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org, and dailyclimate.org. And we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the living on earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Read more about the faces of extinction in 2019

- Read more about the most recently spotted Right Whale Calf off the coast of Georgia

- Reuters | Denmark sources record 47% of power from wind in 2019

[MUSIC: Alison Brown Quartet, “G Bop” on Alison Brown Quartet, by Alison Brown/Gary West/John R. Burr/Rick Reed, Vanguard]

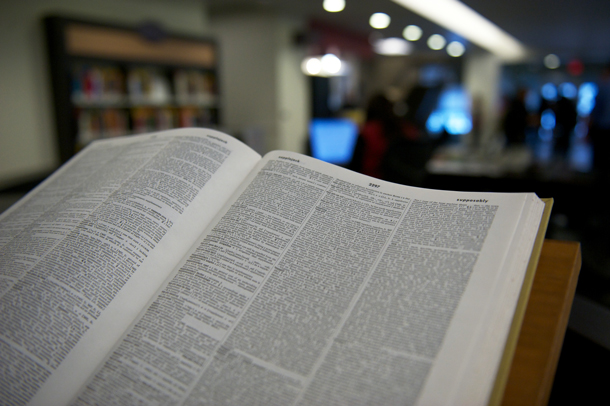

Climate and the 2019 Lexicon

Every year, dictionary publishers select a word or phrase that they call their “word of the year”. They determine this by finding a term that was commonly searched on their websites and speaks to a larger societal theme of that year. (Photo: University of Waterloo Library, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, we are on our way in a new year and a new decade. But Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill takes a look back at the words that defined 2019.

O’NEILL: At the end of the every year dictionary publishers around the world comb through data and statistics to determine a word or phrase that they believe represents that year above all others – their “word” of the year.

They use algorithms to calculate how often people look up a given word on their websites, and then consider whether that word speaks to a broader theme in society.

And for 2019, many of the world’s most prominent dictionaries chose terms relating to climate change.

The Oxford Dictionary declared “climate emergency” as their word of the year.

WOMAN 1: We want governments around the world to declare a climate emergency.

MAN 1: I believe that we have a climate emergency…

MAN 2: To declare an environment and climate emergency…

MAN 3: To declare that we are currently in a climate emergency.

WOMAN 2: The European Parliament has voted to declare a climate emergency…

O’NEILL: Oxford says the term represents a growing public awareness of what the UN Secretary-General has called ‘the defining issue of our time’.

The dictionary’s analysis showed that by September of 2019, the term was more than 100 times as common as it had been the previous year.

And the adjective “climate” placed before the word “emergency” is a relatively new, but steadily growing, trend.

In 2018, according to the Oxford Dictionary, the most commonly searched phrase with the word emergency was health emergency.

But one year later, “climate emergency” was searched for three times as often.

The Oxford dictionary also released a short-list of runner-up words. On it: climate action, climate crisis, and climate denial.

And the Oxford Dictionary isn’t alone.

The Collins English Dictionary selected “climate strike” to represent 2019.

The term was arguably popularized by Swedish activist Greta Thunberg and her Fridays for the Future movement.

She inspired millions of climate strikers around the world to take time off from school or work and hit the streets to demand action on the climate crisis.

Jane Fonda (center) has been participating in weekly climate strikes, partially inspired by Greta Thunberg’s Fridays for the Future Movement. (Photo: Victoria Pickering, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

One such climate striker is Hollywood icon and activist, Jane Fonda, she spoke with Living on Earth about how Greta inspired her participation in climate civil disobedience.

FONDA: We decided to have an action every Friday, because that's when Greta Thunberg and the student climate strikers are having it. We've claimed Friday and they have, I asked their permission first, and they welcomed me to their Friday protests.

O’NEILL: There’s also Dictionary dot com.

Its word of the year was “existential”, meaning “of or relating to existence”.

They say that searches for that word jumped 179% following a town hall meeting when Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders used the term in reference to climate change.

SANDERS: This, to me, is an existential crisis that impacts not just you and me and our generation but our kids and our grandchildren, and we must accept the moral responsibility of leaving these kids, future generations, a planet that is healthy and habitable.

O’NEILL: Dictionary dot com said the term “existential” was chosen because it communicated a sense of humanity grappling with its survival.

The word speaks to fear about the climate, yes, but also fear about political instability and threats to our ways of life.

Past words of the year have also touched on environmental themes. As far back as 2007, Oxford Dictionary selected “carbon footprint”, and in 2018, the Collins English Dictionary chose “single-use” to capture the discussion surrounding plastics and pollution.

But now, the decision of three prominent dictionaries to choose environmentally conscious words for 2019 shows a trend of the world paying more attention to the climate crisis.

The Living on Earth crew gave some thought to a word of the year of our own. Among our most-used phrases was the term “climate action”, used dozens of times on our show throughout 2019.

Climate action refers to the steps we must take to avert climate catastrophe.

Together, these words of the year tell us of a growing awareness of our shared vulnerability. In a sentence:

When confronted with the existential threat of the climate emergency, the ever-growing climate strikes show that the world is calling for climate action.

For Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Related links:

- The Collins English Dictionary | “The Collins Word of the Year 2019 is…Climate Strike”

- OxfordLanguages | “Word of the Year 2019”

- Dictionary.com | “Dictionary.com’s Word of the Year for 2019 is…Existential”

- Click here to hear Living on Earth’s interview with Jane Fonda

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Encounter with a Cassowary

The Southern Cassowary is easily identified by its blue head, grey casque, and red wattle at the back of its neck. (Photo: CC Kirsty Komuso)

CURWOOD: According to a University of Sydney ecologist, the raging wildfires in Australia have claimed as many as a billion animals in the dry bushlands in the southeast of the country. The more tropical northern part of the continent has been spared for now and as BirdNote®’s Mary McCann reports that’s where we find one of the largest, most unusual, birds in the world.

[Cassowary “coughing” calls]

MCCANN: That coughing sound is the call of a Southern Cassowary. It’s a huge, flightless, prehistoric-looking bird, found in the tropical forests of Northeastern Australia, New Guinea and Indonesia.

This bird would look right at home in Jurassic Park. It weighs about 150 pounds and stands nearly six feet tall with a striking bony crest. Its head and long neck are a deep blue... bare and featherless. It looks a lot like an Ostrich, but it’s covered in coarse, black feathers that almost look like fur. Two bright red wattles, like those of a Wild Turkey, dangle from its throat.

The Southern Cassowary is found in the northern forests of Australia. (Photo: CC Brian Henderson)

Cassowaries eat mostly fruit, but they’ll take just about any food that presents itself… plants, frogs, insects and the like. Females are bigger than males, sometimes a lot bigger. Unlike many other birds, males alone incubate the eggs and care for the young up to nine months.

And cassowaries are capable of making remarkable sounds:

[“Roar” of the Dwarf Cassowary]

But how about this call?

[Cassowary subaudible calls]

It’s the lowest-pitched bird call in the world, and it’s barely audible to the human ear.

I’m Mary McCann.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird audio provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Foraging sounds of a Southern Cassowary recorded by L. Macaulay. Queensland ambient recorded by E. Brown.

Various calls of Southern and Dwarf Cassowary recorded and provided by Andrew Mack.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

Editor: Ashley Ahearn

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Assistant Producer: Mark Bramhill

BirdNote’s theme music composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler

© 2019 BirdNote December 2013 / 2019 Narrator: Mary McCann

ID# 120406casso cassowary-01b

https://www.birdnote.org/show/encounter-cassowary

CURWOOD: For photos, strut on over to the Living on Earth website, LOE dot org.

Related links:

- Find out more on the BirdNote website

- Learn more about the Southern Cassowary from Birdlife Australia

[MUSIC: Daniel Champagne, “Waltzing Matilda” Bush ballad/Banjo Paterson]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Anna Saldinger, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth