McSweeney’s ‘2040 AD’ Climate Fiction Issue

Air Date: Week of January 10, 2020

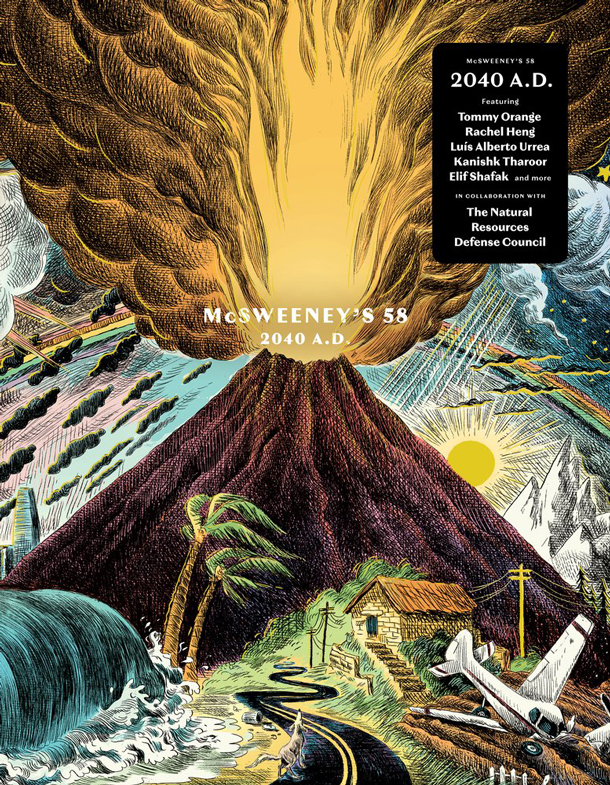

2040 AD spans genres, continents, and iterations of disaster. (Photo: Fabiola Nunez, NRDC)

To convey the climate crisis in a more accessible way, the literary publication McSweeney’s teamed up with the Natural Resources Defense Council for a “climate fiction” issue. “2040 AD” brings together several short stories including “The Night Drinker” by Luis Alberto Urrea. The American-Mexican author joins Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to discuss climate refugees, the innovative spirit of Mexico City, and how literature can advance awareness of the climate emergency

Transcript

CURWOOD: To convey the climate crisis in a more accessible way the literary publication McSweeney’s decided to team up with the Natural Resources Defense Council on a “climate fiction” issue, called 2040 AD. They called on short story authors to envision what the world might be like in twenty years if global temperatures continue to rise. Many of the McSweeney stories paint a grim picture, with democracies collapsing and people left to fend for themselves as resources dwindle. These fictional stories from the future are placed all over the world, from Istanbul to Singapore to Mexico City. And that’s where Luis Alberto Urrea sets his story, “The Night Drinker”, which imagines a dangerously warming world colliding with ancient culture and tradition. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering spoke with Luis Alberto Urrea.

URREA: You know, the genius of it was to pair each of us with essentially a climate scientist who could make sure that we weren't going too far afield in what we were saying and they provided reams of data and interesting information. The hope in it for all of us, I think, is this finding out that it's a, it's a kind of a two- way street. That hard science and the beauty of it and the indisputable hard facts of it could bolster the a little more nebulous and very disputable feelings of what we write, you know, that a fact-based response to what's in fact happening to the world, I think empowered both sides in a really wonderful way.

Author Luis Alberto Urrea reads from his story "The Night Drinker" at the 2040 A.D. release event in Chicago, Dec. 2, 2019. (Photo: courtesy of Fabiola Nunez / NRDC)

DOERING: There's a passage in your story, The Night Drinker, that describes the technological adaptation that goes on in Mexico City. Could you please read us this passage? I think it's on page 52. And it starts with "these aguaceros."

URREA [READING]: These aguaceros, as we called the drenching rains, were fodder for our computer analyses. And by 2035, the government and the scientists of UNAM assaulted our thirst with Proyecto Tlaloc, perhaps the largest drought amelioration project in history. I was there to see it. I was Tlaloc's contracted historian. Rain seemed at first a further punishing apocalypse. Yes, it flooded us. Yes, it brought down mudslides and avalanches. Yes, the refugees and the poor suffered the most, though we all suffered. But we soon saw it was a reprieve if we had the will to take creative action. The kilometers of standing buildings were perfect water collecting sites, like the solar panel and wind turbine platforms they had become, we repurposed them. We created vast networks of flumes and reservoirs to slake our valleys' thirst; the army, the Red Cross, and hordes of volunteers -- many of them, it pains me to say, gringos -- evolved instantly into a disorganized but miraculous bureaucracy of hope.

DOERING: Thank you. So one, one aspect of your story that was kind of surprising maybe to me, it feels hopeful and, and rich and colorful in a way that all these people are coming together even if they are refugees. Mexico City is already a very diverse city. But, even more diverse, culturally. And I wonder if you can just talk a little bit about that, and how you imagine the city, you know, being able to accommodate different groups of people in a way, it sounds like in a kind of a unique way compared to some other, you know, cities around the globe that aren't Mexico City.

Ten short stories set all over the world make up the "2040 A.D." issue of McSweeney's. (Photo: courtesy of NRDC/McSweeney's)

URREA: Mexico City. Yeah, because I think you know, I think one of the brilliant things about Mexico City is it puts the lie to the easy pop culture impression of quote "Mexicans," quote "Mexico," which is a construct, let's face it. You know, there are novels coming out to this day that, talking about the faceless mass of you know, brown people in the slaughter zones and it's not necessarily that way at all. You know, to me the wonder of Mexico City is you can, you can drive from stunning skyscraper disco land, to you know, somebody's little farm with a donkey right there in the town. And Mexico is you know, is doing so much stuff or trying to. They're planting forests in Honduras for the Hondurans to try to mitigate the drought and the famine that's coming. You know, they are planting millions of trees in Mexico City to start processing carbon out of the air again. They're working on all kinds of things, smart buildings, solar, wind generating, you know, green roofs, all that stuff. So in that way, I wanted to make the case for someone from Mexico, and specifically people who are in Mexico City, who are deeply proud of, and in love with the city and consider themselves to be in the premier city of the world, much like New Yorkers do. Right? You know, people in Hong Kong do. And that's not the trope that I see in popular American culture, that Mexicans adore Mexico and are proud of Mexico and in fact, consider Mexico one of the cutting edge countries in the world.

DOERING: Can you talk a bit about how this like moment with, you know, this talk about the border wall and talk about immigration in the United States, how that sort of may have factored into your story.

URREA: You know, what's interesting to me is the tides of refugees, the alleged caravans, etc. etc., which we don't yet, I don't think, have processed that they are largely climate refugees. You know the Haitian population came in response to the hurricanes, you know, initially the big earthquakes and then the hurricanes. And, you know, they could go to Brazil, which they did. And it's, you know, if you have a sense of humor about it, if you go to Tijuana, there are whole sections in Tijuana that have Haitians, and people on the street are learning Haitian French, and some of the taco stands, are now selling Haitian food. And there's a corresponding Trumpian movement, which, to me is weirdly hilarious. They have MAGA hats in Tijuana in Spanish that say 'Make Tijuana Great Again' --

DOERING: No way.

URREA: -- Which to me or, you know, anyone from Tijuana keeps thinking, 'again?' You know, were we a great leader of the world before? But this is all this response, I think, of, of encroachment. And I think what's fascinating about this whole climate crisis is the encroachment, you know, the coming on of desertification, the coming on of massive fires, the coming on of drought, ultimately the coming on of salt water flooding. This is fascinating that there's this thing coming. It's like the, you know, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, right? What beast is coming toward us?

Luis Alberta Urrea is a 2005 Pulitzer Prize finalist for nonfiction and author of 17 books of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. (Photo: Larry D. Moore, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DOERING: Yeah, I feel like I've been hearing inklings of the need for more imagination, in thinking about climate change and more, you know, storytelling and it feels like, like now that I can picture this world that, you know this this dream is sort of like being brought to life for me through these stories. It feels like thinking about climate change is just a little different.

URREA: Well, I think climate change whatever it is, is an evolutionary moment. And I think that you know, our choices are fairly simple, we adapt or we don't. And I think the, you know, the outcome of that is pretty dire honestly. I mean, I don't want to be a, you know, Chicken Little but the chips are on the table, and we have to, we have to be realistic and deal with them. It doesn't mean you know, we're going to tell farmer John, he's terrible, shouldn't have had a pig farm, none of that stuff. Just that this is something we need to work together on as a family. My entire message has always been, there is no them, there is only us, and this entire phenomenon, to me anyway, especially the denial part, is the obsession with them. There's somebody out there, and they're going to come in here and steal my crackers. I've gotta protect them. And there's no, we're only us. There's only, there's only so much room on the rock that we're on. And honestly, especially now with genetics, you're going to find out we all are actually cousins. So what's the problem? Let's save our family. And I think that's what's in the issue. Ultimately, I think it's, it's, it didn't, I don't think it meant to be this, but I think cumulatively it's a bit of a call to arms.

CURWOOD: That’s writer Luis Alberto Urrea speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth