Decoding the Coronavirus

Air Date: Week of January 31, 2020

The Wuhan virus, 2019-nCov, is one of a group of viruses called coronaviruses, which also includes the 2003 SARS virus and the 2013 MERS virus. Coronaviruses get their name from the crownlike appearance of the protein shell surrounding their viral RNA. (Photo: Ben, Flickr, Public Domain)

As a novel coronavirus began spreading from Wuhan, China, scientists from across China collaborated to isolate, sequence, and publish the complete genetic code of the virus, just a month after the first documented case. Columbia University Microbiology and Immunology Professor Vincent Racaniello joined Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss how fast genomic sequencing can help stop the spread of the virus and pinpoint its source.

Transcript

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in for Steve Curwood.

The new coronavirus outbreak likely got its start in the meat markets of Wuhan, China.

While we still don’t know just how infectious the coronavirus is, the deadly virus has been found in several countries in Asia, Europe, and North America. Highly infectious viruses can spread across the world quickly but our ability to sequence their genome, and get a clear diagnosis, has historically lagged behind, taking years in some cases.

But that’s no longer the case. Researchers in China were able to sequence the Coronavirus genome and send that information to colleagues around the world in less than a month. To discuss the advances in genome sequencing I’m joined now by Vincent Racaniello. He’s a Professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, and the host of the podcast, “This Week in Virology”. Vincent Racaniello, Welcome to Living on Earth!

RACANIELLO: Thanks, my pleasure.

BASCOMB: So how concerning is the coronavirus on a large scale? I mean, I've read that more people die or are sickened by the flu than by coronavirus. So is this really something we should be concerned about?

RACANIELLO: I like to say that compared to flu, coronaviruses are amateurs. Flu is the most worrisome virus as far as I'm concerned. It's readily transmitted from person to person, you know, by the aerosols you make when you're speaking or coughing or sneezing, and it can kill a lot of people, it can kill up to 30 or 40,000 people a year in the US. So the coronaviruses, let's put that in perspective. The SARS outbreak, maybe 8000 cases globally, 800 deaths. So these are small numbers, of course, but right now we're in the middle of an unknown. We don't know how far it's going to spread. And that's why people kind of panic about it, but this virus that is currently spreading looks a lot like the SARS coronavirus and so I suspect it won't be much worse than the SARS epidemic. Of course, most of the deaths in China, I think the current total is about 75, most of them are in people over 65. And most of them are in people with other health issues. And so that's very different from flu, which can kill old and middle aged and young people. So this virus, while it's scary that it seems to have an inexorable spread, is really restricted to certain populations in terms of lethality, you know, eventually, I think it will burn itself out.

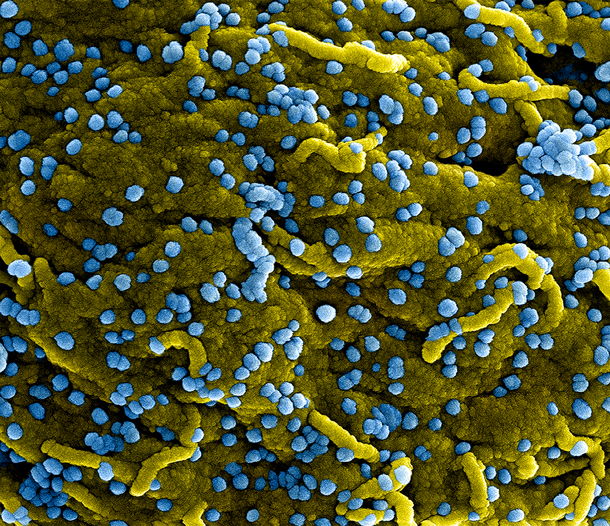

This is a colorized scanning electron micrograph of the closely related MERS virus (blue) attaching themselves to infected cells (yellow). (Photo: NIAID, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, now I understand that the Chinese scientists were able to sequence the entire genome of the new Coronavirus and make it publicly available to other researchers in just a month after the first reported case. How does that timeframe compare with previous genomic sequencing of viruses?

RACANIELLO: So this is amazing. So every organism has some kind of genome -- some of them are really big, some of them are really small, and they specify how to build a new organism. And when I got my PhD in the 70s, there was no sequencing at all, you could not determine any genome sequence. And then the technology emerged over the next few years. So when I was a postdoc, my job was to sequence the genome of polio virus. It took me one year, one year, every day to sequence it, that could be done today, in 30 minutes by a company.

BASCOMB: Wow.

RACANIELLO: So in the intervening years technologies have been developed. And there are multiple technologies called high throughput next-generation sequencing that allow you to sequence any nucleic acid, RNA or DNA, and do it really quickly and with reasonably good accuracy. And when I did my polio virus, I had purified virus, a lot of it. Nowadays, you can have a crude sample, you can have a respiratory wash, you could put a little, you know, saline in your nose and take it out and sequence everything that's in it. And that's why they were able to do that. They took lung wash from one of their patients, and they extracted the, the nucleic acids from it and were able to get the whole genome sequence very quickly. And that is just stunning. And of course, you can do anything, could do a human genome now, 3.2 billion bases. You could do that in a day with the technology. So it's revolutionizing biomedicine.

BASCOMB: Wow. And once you have that information, what can you do with it?

RACANIELLO: You can make diagnostic tests. Once you have the genome sequence, you can make a test that can you can now use to detect the infection.

BASCOMB: Can you also use it to create a vaccine?

Open-air meat markets, such as this one in Yangshuo, are common in Southern China and often trade in exotic animals from the surrounding countryside. After the SARS outbreak in 2003 was traced to a meat market, many were temporarily shut down, but have since reopened. (Photo: TEFL Search, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

RACANIELLO: Sure, you could, say we know that there's a certain virus protein that's important for vaccines so we can take that sequence and synthesize it in cells and make a vaccine. For example, the Ebola virus vaccine that has been used in the West African outbreak, the current DRC outbreak, that was developed having knowledge of genome sequences and the ability to manipulate them, it's a combination of Ebola virus and other viruses. And without the sequence, we couldn't do any of that.

BASCOMB: Does knowing the genetic code give us any clues about where this virus may have come from?

RACANIELLO: Absolutely. The closest sequence is a sequence from a bat virus that was captured in a cave, about 1000 miles outside of Wuhan in 2013. And so, we know most likely this virus originated in a bat. How it got into people we don't know, they do sell bats in the Wuhan markets.

BASCOMB: Hm-mmh. Well it's fascinating, you know, how that the animal human-interactions can result in so many things that animals are just fine with, but humans can be, you know, make them very, very sick.

RACANIELLO: Yeah, that's a growing problem as the population of the world increases enormously. We have more contact with wildlife, we have more encroachment on their areas. And there are numerous examples of, of outbreaks that occur. Good example is one that happened in Malaysia 25 years ago. So they had been clearing forests to make farms. And this clearing of forest, they burn a lot of it, the smoke disturbs the bats which live in the area. And what happened was farmers built pig farms in these cleared areas and they plant mango trees. And the bats that are displaced come and feed on these trees. And these bats have viruses and as they excrete the viruses in their urine and feces, they contaminate the pigs. And so 25 years ago, there was an outbreak of an infection initially in pigs, and then in the humans who take care of the pigs, which was caused by bats, fruit bats in this case, who had been displaced. And so as we do this more and more, we displace wildlife we encroach upon them and many many examples of this, we're going to see more and more infections. This won't be the last coronavirus infection. And there will be other viruses as well that that come from animals as we disturb them into us.

BASCOMB: Well, what does the future look like both in terms of the viruses that we can expect to emerge and the tools that we have at our disposal to protect human health?

Columbia Microbiology and Immunology Professor Dr. Vincent Racaniello hosts a popular podcast on virology, the study of viruses. (Photo: Courtesy of Vincent Racaniello)

RACANIELLO: Well, our tools are just great for detecting new viruses. And so that'll only get better and faster. But what won't change is the emergence of these viruses. And, you know, because there are many, many animals out there besides humans that are infected with viruses, the more we encroach upon them, the more those viruses are going to infect us. Pig growth, for example, pigs pollute the areas where they're living, but also, they get infected with human viruses, and particular influenza viruses, and they can spread them back, especially if the pigs are transported. So that is another issue, just the global massive size of pig farming that has to be regulated in some way. We have to figure out other sources of protein besides living animals, unless we figure out ways to regulate that it's going to be a problem. I mean, we will have rapid ways to respond, but people will die. And we, you know, I don't know at what point people realize that things have to change.

BASCOMB: Vincent Racaniello is a Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at Columbia University and host of the podcast This Week in Virology. Vincent Racaniello, thank you so much for taking this time with me.

RACANIELLO: It's been my pleasure.

Links

The Scientist | "Scientists Scrutinize New Coronavirus Genome for Answers"

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth