January 31, 2020

Air Date: January 31, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Decoding the Coronavirus

View the page for this story

As a novel coronavirus began spreading from Wuhan, China, scientists from across China collaborated to isolate, sequence, and publish the complete genetic code of the virus, just a month after the first documented case. Columbia University Microbiology and Immunology Professor Vincent Racaniello joined Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss how fast genomic sequencing can help stop the spread of the virus and pinpoint its source. (08:33)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

For this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra and Host Bobby Bascomb take a look at findings that sunscreen ingredients can linger in the human body for days. Then the pair looks to China, which now produces 50% more plastic waste than the U.S. Finally, they celebrate the 35-year anniversary of a major Endangered Species Act success: the delisting of the brown pelican. (04:43)

Trump Water Rule ‘Ignores Science’

View the page for this story

The Trump Administration’s new water rule defines “waters of the United States” in a way that will result in far less protection for our rivers and wetlands. Critics of the new rule, including EPA’s own Science Advisory Board, say it has no grounding in basic watershed science. Kyla Bennett, the Science Policy Advisor for PEER, talks with Host Bobby Bascomb about why she believes this rule is devastating for watershed health. (09:45)

Freshwater Mussels: Hunted for Buttons, Stranded by Dams

/ Daniel AckermanView the page for this story

Freshwater mussels are the unsung heroes of river ecosystems, by filtering out bacteria, pollutants and algae. They once were plentiful but in the 1800s they were overharvested for button making and have been severely impacted by dams. Now freshwater mussels are one of the most endangered groups of organisms in the United States. Daniel Ackerman from Minnesota Public Radio reports. (05:36)

BirdNote®: Canada Jays Save Food For Later

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Canada Jays are food storage experts. As BirdNote®’s Mary McCann explains, these prudent birds are so good at caching food, they’re even able to start nesting before the winter ends. (01:51)

Our Wild Calling

View the page for this story

Our modern lives have separated us from other species and contributed to what author Richard Louv calls “species loneliness”. In his book, Our Wild Calling: How Connecting with Animals Can Transform Our Lives – and Save Theirs, Louv shares stories about meaningful interactions between humans and other species and makes the case for their value. Richard Louv joins Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood to discuss how relationships with wildlife can reveal new levels in our humanity. (14:44)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Kyla Bennett, Richard Louv, Vincent Racaniello

REPORTERS: Daniel Ackerman, Peter Dykstra, Mary McCann

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The Trump Administration released a plan for the largest rollback of water protection since 1972 when the Clean Water Act was created.

BENNETT: I truly believe that this is probably the most harmful thing that this administration has done environmentally. This rule will increase flooding in those areas that are getting wetter. And it will reduce protection for drinking water, not to mention fish and wildlife habitat, in those areas that are drier.

BASCOMB: Also, freshwater mussel populations have been in sharp decline since the late 1800s.

DAVIS: They quickly depleted the mussel resource by making buttons out of everybody, and the ones they didn’t make buttons out of they still killed to look for pearls. Because rarely there’s a freshwater pearl and they’re beautiful.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Decoding the Coronavirus

The Wuhan virus, 2019-nCov, is one of a group of viruses called coronaviruses, which also includes the 2003 SARS virus and the 2013 MERS virus. Coronaviruses get their name from the crownlike appearance of the protein shell surrounding their viral RNA. (Photo: Ben, Flickr, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in for Steve Curwood.

The new coronavirus outbreak likely got its start in the meat markets of Wuhan, China.

While we still don’t know just how infectious the coronavirus is, the deadly virus has been found in several countries in Asia, Europe, and North America. Highly infectious viruses can spread across the world quickly but our ability to sequence their genome, and get a clear diagnosis, has historically lagged behind, taking years in some cases.

But that’s no longer the case. Researchers in China were able to sequence the Coronavirus genome and send that information to colleagues around the world in less than a month. To discuss the advances in genome sequencing I’m joined now by Vincent Racaniello. He’s a Professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, and the host of the podcast, “This Week in Virology”. Vincent Racaniello, Welcome to Living on Earth!

RACANIELLO: Thanks, my pleasure.

BASCOMB: So how concerning is the coronavirus on a large scale? I mean, I've read that more people die or are sickened by the flu than by coronavirus. So is this really something we should be concerned about?

RACANIELLO: I like to say that compared to flu, coronaviruses are amateurs. Flu is the most worrisome virus as far as I'm concerned. It's readily transmitted from person to person, you know, by the aerosols you make when you're speaking or coughing or sneezing, and it can kill a lot of people, it can kill up to 30 or 40,000 people a year in the US. So the coronaviruses, let's put that in perspective. The SARS outbreak, maybe 8000 cases globally, 800 deaths. So these are small numbers, of course, but right now we're in the middle of an unknown. We don't know how far it's going to spread. And that's why people kind of panic about it, but this virus that is currently spreading looks a lot like the SARS coronavirus and so I suspect it won't be much worse than the SARS epidemic. Of course, most of the deaths in China, I think the current total is about 75, most of them are in people over 65. And most of them are in people with other health issues. And so that's very different from flu, which can kill old and middle aged and young people. So this virus, while it's scary that it seems to have an inexorable spread, is really restricted to certain populations in terms of lethality, you know, eventually, I think it will burn itself out.

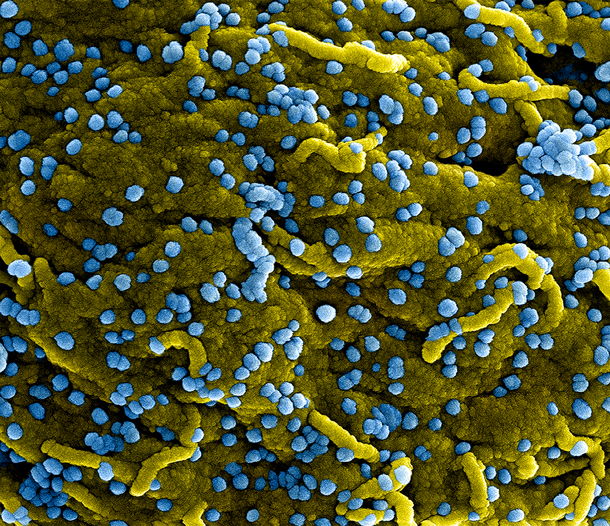

This is a colorized scanning electron micrograph of the closely related MERS virus (blue) attaching themselves to infected cells (yellow). (Photo: NIAID, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, now I understand that the Chinese scientists were able to sequence the entire genome of the new Coronavirus and make it publicly available to other researchers in just a month after the first reported case. How does that timeframe compare with previous genomic sequencing of viruses?

RACANIELLO: So this is amazing. So every organism has some kind of genome -- some of them are really big, some of them are really small, and they specify how to build a new organism. And when I got my PhD in the 70s, there was no sequencing at all, you could not determine any genome sequence. And then the technology emerged over the next few years. So when I was a postdoc, my job was to sequence the genome of polio virus. It took me one year, one year, every day to sequence it, that could be done today, in 30 minutes by a company.

BASCOMB: Wow.

RACANIELLO: So in the intervening years technologies have been developed. And there are multiple technologies called high throughput next-generation sequencing that allow you to sequence any nucleic acid, RNA or DNA, and do it really quickly and with reasonably good accuracy. And when I did my polio virus, I had purified virus, a lot of it. Nowadays, you can have a crude sample, you can have a respiratory wash, you could put a little, you know, saline in your nose and take it out and sequence everything that's in it. And that's why they were able to do that. They took lung wash from one of their patients, and they extracted the, the nucleic acids from it and were able to get the whole genome sequence very quickly. And that is just stunning. And of course, you can do anything, could do a human genome now, 3.2 billion bases. You could do that in a day with the technology. So it's revolutionizing biomedicine.

BASCOMB: Wow. And once you have that information, what can you do with it?

RACANIELLO: You can make diagnostic tests. Once you have the genome sequence, you can make a test that can you can now use to detect the infection.

BASCOMB: Can you also use it to create a vaccine?

Open-air meat markets, such as this one in Yangshuo, are common in Southern China and often trade in exotic animals from the surrounding countryside. After the SARS outbreak in 2003 was traced to a meat market, many were temporarily shut down, but have since reopened. (Photo: TEFL Search, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

RACANIELLO: Sure, you could, say we know that there's a certain virus protein that's important for vaccines so we can take that sequence and synthesize it in cells and make a vaccine. For example, the Ebola virus vaccine that has been used in the West African outbreak, the current DRC outbreak, that was developed having knowledge of genome sequences and the ability to manipulate them, it's a combination of Ebola virus and other viruses. And without the sequence, we couldn't do any of that.

BASCOMB: Does knowing the genetic code give us any clues about where this virus may have come from?

RACANIELLO: Absolutely. The closest sequence is a sequence from a bat virus that was captured in a cave, about 1000 miles outside of Wuhan in 2013. And so, we know most likely this virus originated in a bat. How it got into people we don't know, they do sell bats in the Wuhan markets.

BASCOMB: Hm-mmh. Well it's fascinating, you know, how that the animal human-interactions can result in so many things that animals are just fine with, but humans can be, you know, make them very, very sick.

RACANIELLO: Yeah, that's a growing problem as the population of the world increases enormously. We have more contact with wildlife, we have more encroachment on their areas. And there are numerous examples of, of outbreaks that occur. Good example is one that happened in Malaysia 25 years ago. So they had been clearing forests to make farms. And this clearing of forest, they burn a lot of it, the smoke disturbs the bats which live in the area. And what happened was farmers built pig farms in these cleared areas and they plant mango trees. And the bats that are displaced come and feed on these trees. And these bats have viruses and as they excrete the viruses in their urine and feces, they contaminate the pigs. And so 25 years ago, there was an outbreak of an infection initially in pigs, and then in the humans who take care of the pigs, which was caused by bats, fruit bats in this case, who had been displaced. And so as we do this more and more, we displace wildlife we encroach upon them and many many examples of this, we're going to see more and more infections. This won't be the last coronavirus infection. And there will be other viruses as well that that come from animals as we disturb them into us.

BASCOMB: Well, what does the future look like both in terms of the viruses that we can expect to emerge and the tools that we have at our disposal to protect human health?

Columbia Microbiology and Immunology Professor Dr. Vincent Racaniello hosts a popular podcast on virology, the study of viruses. (Photo: Courtesy of Vincent Racaniello)

RACANIELLO: Well, our tools are just great for detecting new viruses. And so that'll only get better and faster. But what won't change is the emergence of these viruses. And, you know, because there are many, many animals out there besides humans that are infected with viruses, the more we encroach upon them, the more those viruses are going to infect us. Pig growth, for example, pigs pollute the areas where they're living, but also, they get infected with human viruses, and particular influenza viruses, and they can spread them back, especially if the pigs are transported. So that is another issue, just the global massive size of pig farming that has to be regulated in some way. We have to figure out other sources of protein besides living animals, unless we figure out ways to regulate that it's going to be a problem. I mean, we will have rapid ways to respond, but people will die. And we, you know, I don't know at what point people realize that things have to change.

BASCOMB: Vincent Racaniello is a Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at Columbia University and host of the podcast This Week in Virology. Vincent Racaniello, thank you so much for taking this time with me.

RACANIELLO: It's been my pleasure.

Related links:

- The Scientist | "Scientists Scrutinize New Coronavirus Genome for Answers"

- Click here to see the entire sequence of 29903 nucleotide bases which make up the 2019 Novel Coronavirus RNA genome

- Click here to listen to our guest Vincent Racaniello’s podcast “This Week in Virology” and learn about coronaviruses in even more detail

[MUSIC: Yo-Yo Ma & the Silk Road Ensemble featuring Bill Frisell, “If You Shall Return,” Sony Music Entertainment]

Beyond the Headlines

Sun protection is recommended for year-round use, but some active ingredients in sunscreen can be absorbed into the body and remain in the bloodstream for days. (Photo: Allen Lee, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: It's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby, we're going to talk about sunscreen. So what better topic on a frigid mid-winter week? There's new FDA testing of sunscreens that show six common active ingredients are absorbed into the body and can linger for days, sometimes even weeks in some cases. But that testing showed that a single application of sunscreen increases the blood levels of active ingredients beyond the FDA's threshold for determining if they need more study. So that's a big question mark in progress.

BASCOMB: So we don't know if those chemicals in our body are safe? But from what I understand there has been some documented concerns about corals exposed to sunscreen.

DYKSTRA: Right, one of the common UV blockers in sunscreens is a substance called oxybenzone. It's already been banned by the State of Hawaii out of concern that oxybenzone has been proven to impair coral ecosystems. Hawaii made that move in 2018. There are some island nations and tropical jurisdictions that are preparing to follow suit.

BASCOMB: Well, it does make you wonder. I mean, if they're known to be harmful to corals, what are they doing to us? Well, what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: China is neck and neck with the US in greenhouse gas emissions. But they are way ahead according to data from the University of Oxford, in the amount of plastic waste they produce, maybe as much as 50% more than the US.

China has passed an ambitious single-use plastic ban, but plastic-free alternatives might still pose a major pollution problem. (Photo: Gauthier Delecroix, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Wow, that's not really a race you want to win.

DYKSTRA: It's not a race you want to win. But at least the Chinese government has come around to acknowledging the problem. They've planned to phase out plastic straws and single-use bags over the next five years.

BASCOMB: Well, that's great. That's encouraging. But I mean, so much plastic is already out there in the environment, is it too little too late?

DYKSTRA: It probably is too little too late, but at least the problem's getting acknowledged only a few years after we've come to grips with how serious it is. Compare that to something like global warming and climate change. The scientific information's been out there for 40 years in a lot of cases, and we're just now beginning to get around to taking action.

BASCOMB: Right. It seems like you know, the problem of plastic is so much more obvious. Everybody can see plastic pollution, you know, on their beaches and those horrible pictures of sea turtles swallowing plastic bags, whereas climate change, it's more, you know, vague, you can't see it.

DYKSTRA: Speaking of turtles swallowing plastic bags, here's something that's a little bit more gruesome. There's an endangered land tortoise, a giant tortoise that lives only in a few locations in the Indian Ocean. There's an atoll in the Indian Ocean where they found the land tortoise that apparently swallowed and excreted about half of a flip flop.

BASCOMB: At least it came out. You could think something like that might kill a tortoise if it had it stuck in its gut. Well, on that cheery note, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: It's been 35 years since one of the biggest success stories of the Endangered Species Act, and in 1985, the brown pelican was taken off the endangered species list. It had been, like so many birds had been seriously impacted by the pesticide DDT. DDT was banned in '72. Just 13 years later, brown pelicans had recovered enough to get themselves off the list.

The brown pelican was declared endangered in 1970, but it was taken off of the list in 1985. (Photo: Linda Tanner, Flickr, BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Wow, that's amazing. I mean, it says something about what we can do if we're willing to take on these issues. And of course, Rachel Carson should be credited with raising awareness about the hazards of DDT in thinning the eggshells of so many different species of birds.

DYKSTRA: That's right. You can go from some of the smallest birds like ruby threaded hummingbirds to our national symbol, the bald eagle. They've all been slammed by the impacts of DDT on the eggshells. The US Fish and Wildlife Service estimates the global population has boomed from about the low five figures to 650,000 brown pelicans, a species now safe.

BASCOMB: That is good news. Thanks for that, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Thanks, Peter. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on these stories on our website loe.org.

Related links:

- Food and Drug Administration | “Shedding More Light on Sunscreen Absorption”

- Fast Company | “The Problem with China’s Single-Use Plastic Ban: What Will Replace the Plastic?”

- Sky News | “Plastic Pollution: Flip-Flop Found in Poo of Endangered Indian Ocean Tortoise”

- Read more about the brown pelican, courtesy of the US Fish and Wildlife Service

[MUSIC: Ray Charles, “Dawn Ray” on The Genius After Hours, by Ray Charles, Atlantic Masters]

BASCOMB: Coming up – The Trump Administration’s plan to rollback protections for rivers, streams, and wetlands across the United States. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ray Charles, “Dawn Ray” on The Genius After Hours, by Ray Charles, Atlantic Masters]

Trump Water Rule ‘Ignores Science’

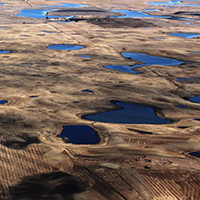

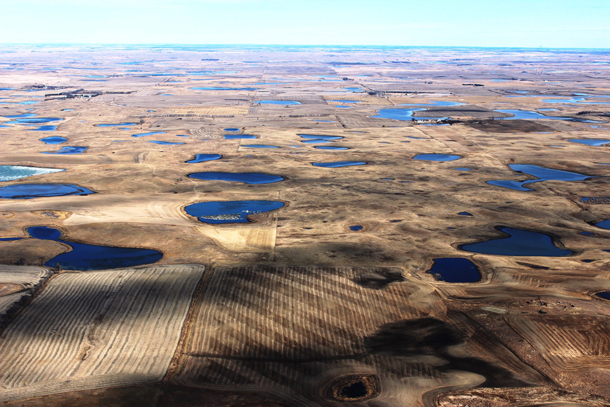

The Prairie Pothole Region of the United States and Canada is where over half of North America's waterfowl nest. This area is referred to as the "Duck Factory". (Photo: Krista Lundgren, USFWS)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

When it comes to environmental protection, President Trump frequently emphasizes the importance of clean air and water.

PRESIDENT TRUMP: From day one, my administration has made it a top priority to ensure that America has among the very cleanest air and cleanest water on the planet. We want the cleanest air. We want crystal clean water. And that’s what we’re doing, and that’s what we’re working on so hard.

BASCOMB: Despite the President’s pledge to clean up American waterways, his Administration recently released a plan to dramatically reduce protections for many of the nation’s rivers and streams and roughly half our wetlands. That move is despite the recommendations of the Environmental Protection Agency’s own Science Advisory Board, which found the new clean water rule quote “neglects established science” by “failing to acknowledge watershed systems”. For more I’m joined now by Kyla Bennett. She is the Science Policy Advisor for PEER, Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility. Welcome to Living on Earth!

BENNETT: Thank you so much for having me.

BASCOMB: So how will the Navigable Waters Protection Rule proposed by the Trump administration change the way we protect our waterways?

BENNETT: Well, first of all, I'd like to point out that the name is an oxymoron, because it's not going to protect navigable waters or any other waters for that matter. What the Trump administration has done is they have removed protections from all ephemeral streams across the country, and all what they call geographically isolated wetlands. But unfortunately, because they ignored all the science, what they don't tell us is that both the ephemeral streams and these geographically isolated wetlands are indeed connected to downstream waters and they affect them greatly. So what's going to happen is if they allow the pollution of or filling of these streams and wetlands, we are going to have a lot of pollution downstream in the truly navigable waters and the more permanent waters and wetlands. If you look in New Mexico, for example, the Santa Fe River is ephemeral in places. I mean, that's a tributary to the Rio Grande. And it's a big river. But because it's so dry out there, and because it's so hot, there's a lot of evapo-transpiration, that water is pumped out of the river. And about 40% of Santa Fe's water supply comes from the Santa Fe River. But now the portions of it that are ephemeral will no longer be protected, and people can dump anything into it. And that's drinking water.

Wetlands provide critical migratory bird habitat for species like sandhill cranes, seen here enjoying Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge in New Mexico. (Photo: sunrisesoup, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: And from what I understand this rollback goes beyond just the regulations that the Obama administration put in place, but actually goes back to 1972 when the Clean Water Act --

BENNETT: Correct.

BASCOMB: -- was initially passed. I mean, this is the biggest rollback in all that time, is that right?

BENNETT: It is. And I truly believe that this is probably the most harmful thing that this administration has done environmentally, it's going to have lasting and irreversible impacts if it doesn't get stopped. So this is really, really devastating news for the entire country. Because, especially with climate change, which, contrary to what this administration believes, it's here, it's real. It's causing more flooding, it's causing more droughts in some areas of the country. And this rule will exacerbate the impacts of climate change. So it will increase flooding in those areas that are getting wetter, and it will reduce protection for drinking water, not to mention fish and wildlife habitat, in those areas that are drier.

BASCOMB: Well, why did the Obama administration feel it was necessary to create the Clean Water Rule in the first place?

A vernal pool surrounded by a riot of wildflowers at California’s Carrizo Plain National Monument. Vernal pools are by definition ephemeral ponds that may be completely dry through most of the summer and fall, yet they provide critical habitat for amphibians and other life. (Photo: Mikaku, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BENNETT: Unfortunately, the Clean Water Act is a little fuzzy on how the regulators are supposed to restore and maintain the biological, physical, and chemical integrity of the nation's waters. And it has been litigated extensively. I freely admit that it has been confusing. And the reason the Obama administration came out with the 2015 Clean Water Rule was to try to clear up some of that confusion because the Supreme Court had a couple of cases that led to some pretty confusing things. People didn't know what was going on. So it was hard for the regulators, it was hard for the regulated public. And the 2015 Clean Water Rule made it easier. But it also happened to expand jurisdiction a tiny bit in some parts of the country. And that really made a lot of businesses and farmers angry.

BASCOMB: But from what I understand there were quite a few exceptions in that rule put forth by the Obama administration.

BENNETT: Oh, absolutely. And particularly for farmers. You know, it's kind of ironic that farmers are so against the new definition in 2015 and so supportive of this new Trump definition, because farming was one of the exemptions. If you had an active farm, you could do whatever you wanted, basically, to continue farming that property. There were no permits necessary, no mitigation necessary. The issue was if you wanted to create new farmland out of existing natural wetlands, then you needed a permit. And they didn't want to bother to do that. And so that's been the problem. They've always been exempt, farmers have always been exempt for doing normal agricultural activities. But they were not exempt if they were going to convert wetlands into cropland.

The Santa Fe River runs dry part of the year along some of its length, including where it is channeled through the city of Santa Fe, New Mexico. (Photo: Chris English, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

BASCOMB: So you mentioned that farmers and agriculturalists were in favor of this new rule. But what other industries stand to benefit?

BENNETT: The National Home Builders Association has been very supportive of this new rule. And also a lot of the cattle farmers like the National Cattlemen's Association, I think it's called have been very supportive of it. And then also oil and gas drilling. Even pipelines, because if you think about it, like the Dakota pipeline or Keystone, they had to cross a lot of ephemeral streams to put those pipelines in and now they'll no longer need federal permits to do so.

BASCOMB: And President Trump was, of course, a developer and owns several golf courses. How likely is it, do you think, that he was hampered in some of his previous work by this rule?

BENNETT: Oh, he absolutely was he absolutely had to apply for permits for some of his buildings and golf courses. People stand to make a lot of money out of being able to develop in areas that they previously weren't allowed to develop in.

BASCOMB: What about state and local laws? I mean, surely those will still be in place.

BENNETT: Yes, but unfortunately, only about half of the states have state laws. So there are states like Texas that have no protection outside of federal law for wetlands and waters. And then there are states like New York, for example, which, New York only regulates wetlands that are greater than 12.4 acres in size. So states that have no protection or have weak laws will suffer the most. The reason we need federal laws for things like clean water or clean air or endangered species is that water, air and wildlife do not respect political boundaries. So what happens upstream in one state can really mess up a state downstream. So if you leave it up to the states, there are going to be states downstream of states that don't care who are going to get nailed by this, even if they are trying to do the best to protect their own waters. This is why we have federal environmental laws, and the Trump administration seems to have forgotten that.

Wetlands provide a buffer during floods as well as drought, and they purify water that moves through them. (Photo: Dave Cornwell, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, your organization, PEER, has requested that the EPA Inspector General conduct an inquiry, what's the status of that request?

BENNETT: So they have received it, we sent it to both the Inspector General and also the Scientific Integrity Officer. The status is that they said they're going to look into it. But I am afraid that this will get swept under the rug. We're asking for a congressional hearing. People need to know what was done. You know, EPA claims that the regions where all the experts are, the 10 regions of EPA have scientists and lawyers who are specialists in wetland science and wetlands law. They claim that these 10 regions were involved in the drafting of this rule. But yet the regions do not appear to have received the final rule until the day it was published just last week. They didn't see the language of the rule until the rest of us did. So to me, that does not sound like they were involved.

BASCOMB: Well, you used to work for the EPA, what are you hearing from former colleagues and current EPA employees about this rollback?

BENNETT: They're horrified as evidenced by our IG complaint and our complaint to the Scientific Integrity Officer, it was signed on by about 45. And I still have people calling me asking if they can sign on. And those are both former EPA people, including three Regional Administrators, and also current employees who signed on anonymously. They are absolutely horrified. And I want everybody to know that the career people at EPA across the country and at headquarters, the non-political appointees, are doing everything they can to try to show the public what is really going on there. And I think we all have to respect them and applaud them for their courage. It's not easy being a whistleblower. It's not easy being an environmentalist under this administration, and they all deserve our respect and support.

BASCOMB: Kyla Bennett is the Science Policy Advisor for PEER, Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility. Thank you so much for taking this time with me, Kyla.

BENNETT: Thank you so much for having me and for talking about this important topic.

BASCOMB: We reached out to EPA for comment and they sent a statement that reads in part, “The agencies’ definition of ‘waters of the United States’ is informed by science, but science cannot dictate where to draw the line between federal and state or tribal waters.” You can find the full statement on the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

EPA statement on the Navigable Waters Protection Rule, attributable to an EPA Spokesperson:

"In the Clean Water Act, Congress gave explicit direction to protect “navigable waters.” The Navigable Waters Protection Rule regulates these waters and the core tributary system that provides perennial or intermittent flow to them. The agencies’ definition of “waters of the United States” is informed by science, but science cannot dictate where to draw the line between federal and state or tribal waters, as those are legal distinctions established within the overall framework and construct of the Clean Water Act.

The legal rationale for the Navigable Waters Protection Rule is clearly articulated in the final rule preamble. As described in the preamble, the final rule is primarily guided by the statutory authority delegated by Congress under the Clean Water Act and the legal precedent set by key Supreme Court cases. The agencies are precluded from exceeding their delegated authorities to achieve specific policy, scientific or other outcomes."

Related links:

- EPA.gov | Final Rule: The Navigable Waters Protection Rule

- Read the PEER Scientific Integrity Complaint about the Trump water rule

- Read the EPA Science Advisory Board draft commentary on the rule

- NYTimes | “Trump Removes Pollution Controls on Streams and Wetlands”

- Union of Concerned Scientists blog: “EPA’s New Water Rule a Mockery of Science and the Clean Water Act”

[MUSIC: Little Sonny, “Wade In the Water” on Black & Blue, traditional, Fantasy]

Freshwater Mussels: Hunted for Buttons, Stranded by Dams

Freshwater fishermen and their fishing harvest in Mississippi, 1904. (Photo: Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society)

BASCOMB: Well, changes to the rules protecting our waterways proposed by the Trump Administration are expected to harm much of the wildlife who make their homes in our rivers, streams, and wetlands. And high on the list are freshwater mussels which are already losing habitat to dams and warming water. As filter feeders, they pull chemicals from water and retain that contamination in their bodies. Dozens of freshwater mussel species have already gone extinct in the US and most of those remaining are at risk of extinction. And as Daniel Ackerman of Minnesota Public Radio reports, their populations have actually been in sharp decline for more than a century.

ACKERMAN: Gary Wagenbach opens a jar full of shiny iridescent buttons. We're sitting in the wooded yard in front of his house in Northfield. He picks out a button about the size of a quarter.

WAGENBACH: It's polished and has four holes in it. It's a beautiful opalescent pearl.

ACKERMAN: At some angles the button looks white, but when it catches the sunlight, it bursts into a rainbow of color.

WAGENBACH: Gorgeous button.

A freshwater mussel harvest from the Mississippi river in 1900. (Photo: Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society)

ACKERMAN: These buttons were made from the pearly shells of freshwater mussels. They were plucked from streams here in the upper Midwest over a century ago. Wagenbach is a mussel biologist, now retired from Carleton College. He spent a career studying the creatures, but these mussel shell buttons aren't for research. They're a family heirloom.

WAGENBACH: So these are from my, my grandmother's collection. She was born back in the 19th century. She and my mother lived on, on farms in Wisconsin, northern Wisconsin. They were pioneer families.

ACKERMAN: Wagenbach's grandmother made her own clothes like pretty much everyone else back then. And buttons were a luxury good, expensive to produce. That changed in the 1890's when a German immigrant named John Boepple came to the US with a machine kind of like an industrial-scale cookie cutter. It punched buttons out of materials like cattle horns. But Boepple soon found a new and abundant raw material to work with: mussels. DNR biologist Mike Davis explains.

DAVIS: He was wading in a river and started picking up some of these, and I guess to eat them for supper, and then he noticed the shells were thick enough that he thought 'I bet I could make a button.'

ACKERMAN: And Boepple did just that. He set up a factory along the Mississippi River in Muscatine, Iowa. His mass-produced buttons fed a growing nationwide demand and made buttons more accessible for everyone. But it was bad news for river ecosystems. Mussels play a vital role in filtering water, and they serve as a food source for other animals. With the button makers in town,

DAVIS: They're quickly depleted the mussel resources by making buttons out of everybody.

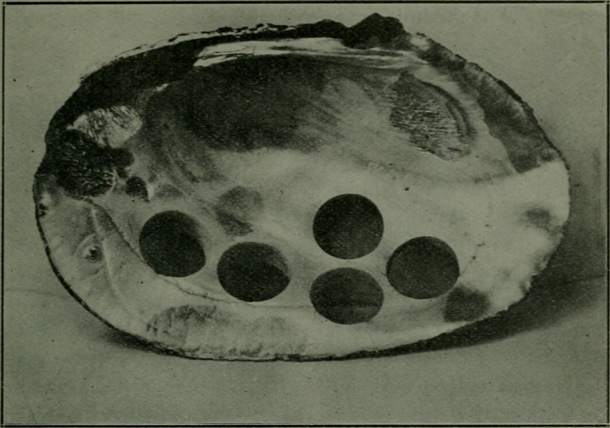

A washboard shell cut out to make five buttons in 1913. (Photo: Internet Archive Book Images, ‘Pearls and Pearlings by Herbert Harvey, Flickr)

ACKERMAN: By the early 1900's, the US button industry plowed through enough shells each year to outweigh the Statue of Liberty.

DAVIS: The ones that they didn't make buttons out of they still killed to look for pearls, because rarely there's a freshwater pearl occurs and they're beautiful. They really have unique shapes and colors to them.

ACKERMAN: Pearl hunters looking for a quick score built makeshift camps outside Northfield and other river towns. They spent entire summers scouring the river beds and prying open mussel shells. Mostly they came up empty. But Wagenbach says the process killed a lot of mussels.

WAGENBACH: The number of shells dead and dying on the banks of the river created a terrible stench, and people were really upset with the pearl hunters because it created a stench over the entire town.

ACKERMAN: Harvesting mussels for pearls and buttons did eventually wind down. One reason, with so few mussels left the odds of finding a pearl were slim to none. And by the mid 1900's, there was a new technology on the market.

CURRY: Yes, plastic.

ACKERMAN: Tierra Curry is a senior scientist with the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity,

CURRY: Buttons started to be made of plastic. And then the freshwater pearl industry kind of fell off.

ACKERMAN: Cheaper plastic buttons were even made to mimic that authentic mussel shell look. But the dawn of plastic didn't mean mussels were in the clear.

CURRY: After the button industry, the, the first really big threat was dams.

This picture shows a freshwater fishermen along the Mississippi River around the 1900s. (Photo: Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society)

ACKERMAN: Minnesota alone has about 1100 dams.

CURRY: And they reduce the amount of dissolved oxygen and they change the water temperature and the flows. And they also cut off the mussels from the host fish that they need to reproduce.

ACKERMAN: While dams muddied America's rivers, industrial pollution turned to them toxic. Curry says the Clean Water Act of the 1970's improved water quality, but it came too late for many of America's mussels. 38 species have disappeared from US waterways. That's one in every eight species that used to live here, and more are at risk today.

CURRY: Yes, it's actually really sad, 70% of freshwater mussels are at risk of extinction.

ACKERMAN: Curry fears the downward spiral of native mussels could continue. They're threatened by the effects of climate change, invasive mussels, and pesticides that trickle into streams from lawns and farms. But Curry still sees room for optimism.

CURRY: There's a lot of scientists who are very passionate about freshwater mussels. There's like this whole group of people who learn about them and are obsessed with them and start figuring out how to save them.

ACKERMAN: And many of those scientists, they're working right here in Minnesota, helping native freshwater mussels bounce back in rivers across the state.

BASCOMB: Daniel Ackerman is an environmental reporter for Minnesota Public Radio. He reported a series of stories on fresh water mussels, for links to those reports and some historical photos he put together, check out our website, LOE dot org.

Related link:

MPR News | “The Unnatural History of Minnesota’s Freshwater Mussels”

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Canada Jays Save Food For Later

The Canada Jay uses sticky saliva to glue food under tree branches. (Photo: © Claudine Lamothe)

BASCOMB: The long cold winters of the far north may look rather inhospitable. But some birds have clever ways to find, and store, enough food to get by. BirdNote’s Mary McCann reports.

BirdNote®

Canada Jays Save Food for Later

[Wind blowing through a forest of coniferous trees]

MCCANN: Imagine you’re camping in the mountains, surrounded by pines, larch, and spruce. The very first bird you might see is a Canada Jay, as it boldly swoops down into your camp.

Canada Jays store large quantities of food for later use. (Photo: © Nick Saunders)

[Canada Jay calls -- https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/13510 ]

This handsome jay has a smoky gray back and wings, silvery gray underparts, a tiny black beak, and big, black eyes that seem to miss nothing — especially food.

[Canada Jay scolding calls - https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/13510 1:37 ]

But the one food Canada Jays don’t eat is conifer seeds. So why do they live in conifer forests?

[Canada Jay whistles - https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/13510 1:25]

It turns out the jays hide food in conifer needles and tuck it under the bark of trees with their sticky saliva. Like other jays that cache food, Canada Jays have terrific visual memories. They can find thousands of hidden tidbits months later.

Canada Jays are so good at storing up food, they even start nesting before the winter ends. The jays can feed their nestlings entirely from the food they’ve stored away. And unlike most other birds that nest in spring and summer, Canada Jays spend that time caching food for the next winter.

[Canada Jay family chatter -- https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/207146 ]

###

Written by GrrlScientist

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by Bob McGuire and Charles A. Sutherland.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

Editor: Ashley Ahearn

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Assistant Producer: Mark Bramhill

© 2020 Tune In to Nature.org January 2018 / 2020 Narrator: Mary McCann

ID# GRAJ-02-2018-01-08 GRAJ-02b

https://www.birdnote.org/show/canada-jays-save-food-later

BASCOMB: For pictures, fly on over to the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- Learn more on the BirdNote website

- Canada Jay – More at Audubon’s Guide to North American Birds

- Canada Jay facts from All About Birds

- Read about the Canada Jay in John James Audubon’s Birds of America

[MUSIC: Adrian Legg, "Paddy Goes To Nashville" on Mrs. Crowe's Blue Waltz, by Adrian Legg, Relativity Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Author Richard Louv on exploring how relationships with wildlife can reveal new levels in our own humanity. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Charlie Haden and Hank Jones, “Wade In the Water” on Steal Away, traditional, Decca Records]

Our Wild Calling

Our Wild Calling spans a wide array of human and animal interactions, including zoos and robotic dogs. (Photo: Courtesy of Richard Louv)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Many pet owners will tell you that they have a profound relationship with their animals.

Dogs are man's best friend, after all, and cats can be aloof yet beloved housemates.

But even as many of us live with pets, modern life often alienates us from animals in the natural world. In his new book, Our Wild Calling, Richard Louv explores that disconnect and the moments that can feel magical when we do make a meaningful connection with wildlife. Author Richard Louv spoke with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: So after writing a book that centers on them, why do you think it's important that we examine the relationships between humans and animals? I mean, what do all species stand to gain when we think about, when we reflect on these relationships and, and what's at stake if we don't?

LOUV: That's a great way to put it, what do all species stand to gain. This is not only about us and what we stand to gain in terms of mental health and even physical health and spiritual health, but also the preservation of these species that are all around us. In the book, I have something I call the reciprocity principle, which we'll talk about later. What we have to gain I think most of all, right now, at least in the current society, there's an epidemic of human loneliness that medical folks are talking about. And they're saying that human loneliness, isolation, may soon surpass obesity as a cause of early death. That's a remarkable thing. And it's not just because of suicide, it's because of all the diseases that are associated with human loneliness. I make the case in Our Wild Calling that human loneliness is rooted in an even deeper loneliness, which is species loneliness. We are, for example, urban parks that have the best psychological impact on human beings, studies show, are the parks that happen to have the highest biodiversity. I don't think that's an accident. I think we are desperate to feel not alone in the universe. Why else would we look for Bigfoot, you know, or intelligent life on other planets when that may not be a good idea to find? We really don't want to be alone in the universe.

CURWOOD: Richard, your book is threaded together by some really wonderful examples of meaningful moments shared between humans and animals. Talk to me about an encounter you've had and what made it stand out for you.

LOUV: One example of a story that I tell in the book is I was on a lake once, near San Diego, and I have a little electric motor on my boat. And I saw on the shore what I thought were two vultures. And I eased up with my electric motor and got within about 20 feet and they were not vultures. They were two really big golden eagles. And they were eating a dead carp on the shore. And you don't usually get within 20 feet of golden eagles. And they stayed there. I stayed there. One of them flew away for a minute, went up to a peak and then came back. And then for what seemed forever, they would dip down, take a bite of the fish and then look back up at me straight into my eyes. Their eyes actually never left my eyes up and down, up and down as they ate. I felt, and I know this sounds New Agey, but I felt something shift there between me and the eagles. And it was the same thing that I heard later from person after person who told me similar stories. So I went home. I talked to my younger son Matthew who was home from college, and I said 'Matthew, this thing happened. And I, you know, I can't really explain it but whatever, whoever I say I am, I'm not. Whoever I was in those moments is actually who I am.' I don't have the words to explain this. This is, I think beyond human language. I have some theories about what, what that is. But that's similar to what I heard time after time, including from hardcore scientists who would, wouldn't get close to anything that smacked of anthropomorphism.

Richard Louv has felt a special connection with many wild animals, including a pair of golden eagles he saw on the shore of a lake. (Photo: carfull, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It can be so hard to find the right language to capture those experiences, those, those relationships. In fact, in your book, you mentioned, one of the impulses that these encounters spark is the urge to describe them as being some kind of magic. How does this word affect people and what do you think of that?

LOUV: Well, that's a troubling word. We tend to shy away from that, but we have to find some words for this. One of the ways to describe this is there's a great philosopher named Martin Buber, who wrote a great essay called I and Thou. It was about you and me. It was about human relations. And he said that you and I don't actually exist. What exists is between us. It's the relationship, he thought of it as a kind of electricity that some people call God. And I apply that really to the experiences and relationships we have with other animals, whether they're our dog or a bobcat walking through our backyard, it stops and looks at us, or those eagles on the shore. What is that thing between us? What is that that happens? So in Our Wild Calling, I decided to name that and I call that the habitat of the heart. And I believe that there are two habitats. One is the physical habitat that we spend a lot of time and money trying to protect, and we do, as we should. And then there's this other habitat, the habitat of the heart, and we spend hardly any time and hardly any money trying to preserve that or explore it, or nurture it. But here's the deal, if one of those habitats goes, so does the other one.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about reciprocity, why that's important to understand.

LOUV: Well, I came to the conclusion, this is at the end of the book. And if you don't mind, I'd like to read a few sentences that describe it, because I, I'm better at reading those that I am describing it. Basically it builds on the values that we already recognize in terms of the exploitation ethic that obviously takes from nature and then there's the nurturing ethic that gives back or gives to nature, but what I talk about in terms of reciprocity is that it goes both ways. We really need to focus on that in our individual lives, but also in our public lives. So I think the times call for an adoption of this basic principle that embraces both survival and joy and we need that to repair our relationship with the natural world. The reciprocity principle as I describe it, is for every moment of healing that humans receive from another creature, humans will provide an equal moment of healing for that animal and its kin. For every acre of wild habitat we take, we will preserve or create at least another acre for wildness. For every dollar we spend on classroom technology, we will spend at least another dollar creating chances for children to connect deeply with another animal, plant or person. For every day of loneliness we endure, we'll spend a day in communion with the life around us until the loneliness passes away.

CURWOOD: Let's jump ahead to a moment, to domesticated animals, and I'm thinking particularly of therapy animals that frankly, they've gotten kind of negative attention over the last few years. What's this famous example of a, of a woman who tried to bring her therapy peacock onto a plane?

Dogs have a way of connecting with humans, honed over thousands of years, that makes them great service animals as well as therapy dogs. (Photo: Marvin Kuo, CC BY 2.0)

LOUV: You know, I talk about that in the book. I spend at least two chapters in there talking about the rise of animal assisted therapy. Now there's two brands of this. One is the kinds of dogs that are trained to do this, formal training service dogs, but also formal training of therapists who use animals in the therapy, for instance, equine therapy, horse therapy. Then there's this other kind, which is growing even faster. Both of these are growing. The other kind is the companion animal. A young woman who is on the autism spectrum, who also has an additional condition, a kind of schizophrenia that was only discovered recently and I think she's 22 or 23. She and her mother came up to Julian, we sat in the coffee shop and talked for a long time with their dog, Kobo. Kobo is not only sensitive and has been trained on the autism symptoms. He's taught himself about the schizophrenia symptoms. One of the things he does is he, he gets on her lap, slowly pushes her to the floor with his weight, big dog, and holds her down as much as he can. You know how a cat can become heavier when it wants to be? Kobo does that. And it turns out when Kobo is in danger, this young woman does the same thing with Kobo. She's learned from Kobo to calm Kobo, so it's reciprocal. I found that very moving. And you know, she told me she can, we were sitting there at the table in the cafe she says that, you know, she can kind of read Kobo's mind as well as he can read hers. And I said, 'Okay, well, what's Kobo thinking right now?' She said, 'he says he's kind of bored.' That animal assisted therapy of both of those kinds is growing very rapidly. There's a professor at the University of Denver, who's an expert on this, he told me he thinks is this is one of the fastest growing types of therapy in our culture. And there are good reasons for that. And there are good reasons also to be careful with that.

CURWOOD: So there are moments when we immerse ourselves in the natural world to connect with animals. But increasingly, there are also times that we're now using technology to do this connection, right? I mean, you write about an attempt to use artificial intelligence to translate prairie dog calls into a human language and then back again so that we can have a two-way conversation with them.

LOUV: That's a, that's a scientist, his name I can never pronounce but it's Con Slobodchikoff, but he's doing fascinating work with prairie dogs.

CURWOOD: Yeah, but what could we lose by putting this conversation with prairie dogs into our terms?

LOUV: Well, I do write about this with some skepticism. Even so, it's pretty fascinating. He's been recording prairie dog language sounds for quite a while and then moving them through a computer and decoding them. Prairie dogs of all the animals that have been studied in terms of their sounds and signals have been studied more than any other animals, according to him. And he believes it's possible that we will be able to feed those sounds into a computer that translates them into another sound in English or whatever, French, whatever languages that we use. And vice versa. We'll be able to speak into a computer and have that deliver that message to prairie dogs in their language. And their languages is really pretty amazing. They're like really good journalists and they don't do fake news. There's a prairie dog that stands at the edge of the prairie dog town. If he sees a guy approaching with a white shirt, and dark pants, he could report that in that kind of detail. He lets the others know and they pass it on down through until the whole town knows. Amazing amount of detail and complexity in that language. Now, should we do that? Do we need to do that? Probably one of the most extreme examples, and I think it's kind of ridiculous, is there are some researchers are working on a special leash attached to a special vest on your dog that will tell you what your dog is thinking or smelling or feeling. And I think that's pretty strange because we've had at least 30,000 years at coevolution. And like the young woman with autism spectrum, we pretty much know what they're saying. And they pretty much know what we're saying.

CURWOOD: There are many, many, many stories written usually for children, in which animals talk. Why is that so important? To tell stories of animals speaking? It's also by the way, in indigenous cultures, if you listen to their stories, not just for kids, but for everyone, the animals are speaking either literally with words or, you know, with their body language symbolically. Why do we need animals to talk to us?

Prairie dogs communicate using a remarkably complex language (Photo: Pixel.la, Flickr Public Domain)

LOUV: I think one of the messages I hope this book, Our Wild Calling, is that we need to tell stories. We need to tell about that. I asked the famous wildlife artist Robert Bateman in Canada once, when I walked into his center his, where he has all of his art displayed that I helped open for him. I saw his artwork for the first time. His giant bear was, I thought, stepping out of the picture. I saw it. I said, Bob, how do you do that? He said, I become the bear. Now when we tell stories, I told stories to my kids using stuffed animals. Who hasn't who has kids? And they took on their own personalities. My sons gave them their personality. We have Chico, who's a sock monkey, who's really kind of a nasty little guy. Yeah. And they tell each, and then the stuffed animals tell each other stories. And my sons would act out things, talk out things that they felt funny about bringing out verbally as their own voice, but they came out through Chico. That's one of the reasons why it's important to tell these animals stories. One things I found is that in there, there are probably about 100 of these stories that people told me in the book. One of the things that I found is that some of them had never told that story before because they're embarrassed. But once they tell it, they find even more meaning in that story than they did to begin with. The more they tell it the more meaning, now that's very old. That's the in us. That's part of who we are, part of our humanity. It's one of the reasons why I'd love for people who read this book to sit around the dining room table and tell some animal stories to each other as families. At least two people I've heard from recently have told me they're reading the book to their kids, when I'm actually next to a fireplace, and they're telling animal stories. These stories have great meaning. It doesn't really matter to me whether that meaning is intrinsic in some fashion of magic, or whether we project that meaning into that, you know, not taking away the animal soul, but giving ourselves a deeper soul by telling that story.

BASCOMB: That’s author Richard Louv speaking with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood about his new book, Our Wild Calling.

Related link:

Richard Louv’s bio and his other books

[MUSIC: Yo-Yo Ma Ma, “If You Shall Return”]

[PRAIRIE DOG SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: We leave you this week in the company of Prairie Dogs.

[PRAIRIE DOG SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Prairie dogs are rodents and not related to dogs at all; rather their name comes from the barking sound they make as a warning.

[PRAIRIE DOG SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: They have distinct calls for different predators.

One for an eagle, another for a coyote or snake.

Prairie dogs hearing the alarm react differently based on the type of threat.

For a coyote they stand outside the entrance of their burrow and watch the predator.

For a human threat prairie dogs immediately take cover in their underground burrows.

[PRAIRIE DOG SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: These prairie dogs were recorded in northern New Mexico by researcher John Hoogland.

[MUSIC: Yo-Yo Ma Ma, “If You Shall Return”]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Anna Saldinger, Candice Siyun Ji, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth