Freshwater Mussels: Hunted for Buttons, Stranded by Dams

Air Date: Week of January 31, 2020

Freshwater fishermen and their fishing harvest in Mississippi, 1904. (Photo: Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society)

Freshwater mussels are the unsung heroes of river ecosystems, by filtering out bacteria, pollutants and algae. They once were plentiful but in the 1800s they were overharvested for button making and have been severely impacted by dams. Now freshwater mussels are one of the most endangered groups of organisms in the United States. Daniel Ackerman from Minnesota Public Radio reports.

Transcript

BASCOMB: Well, changes to the rules protecting our waterways proposed by the Trump Administration are expected to harm much of the wildlife who make their homes in our rivers, streams, and wetlands. And high on the list are freshwater mussels which are already losing habitat to dams and warming water. As filter feeders, they pull chemicals from water and retain that contamination in their bodies. Dozens of freshwater mussel species have already gone extinct in the US and most of those remaining are at risk of extinction. And as Daniel Ackerman of Minnesota Public Radio reports, their populations have actually been in sharp decline for more than a century.

ACKERMAN: Gary Wagenbach opens a jar full of shiny iridescent buttons. We're sitting in the wooded yard in front of his house in Northfield. He picks out a button about the size of a quarter.

WAGENBACH: It's polished and has four holes in it. It's a beautiful opalescent pearl.

ACKERMAN: At some angles the button looks white, but when it catches the sunlight, it bursts into a rainbow of color.

WAGENBACH: Gorgeous button.

A freshwater mussel harvest from the Mississippi river in 1900. (Photo: Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society)

ACKERMAN: These buttons were made from the pearly shells of freshwater mussels. They were plucked from streams here in the upper Midwest over a century ago. Wagenbach is a mussel biologist, now retired from Carleton College. He spent a career studying the creatures, but these mussel shell buttons aren't for research. They're a family heirloom.

WAGENBACH: So these are from my, my grandmother's collection. She was born back in the 19th century. She and my mother lived on, on farms in Wisconsin, northern Wisconsin. They were pioneer families.

ACKERMAN: Wagenbach's grandmother made her own clothes like pretty much everyone else back then. And buttons were a luxury good, expensive to produce. That changed in the 1890's when a German immigrant named John Boepple came to the US with a machine kind of like an industrial-scale cookie cutter. It punched buttons out of materials like cattle horns. But Boepple soon found a new and abundant raw material to work with: mussels. DNR biologist Mike Davis explains.

DAVIS: He was wading in a river and started picking up some of these, and I guess to eat them for supper, and then he noticed the shells were thick enough that he thought 'I bet I could make a button.'

ACKERMAN: And Boepple did just that. He set up a factory along the Mississippi River in Muscatine, Iowa. His mass-produced buttons fed a growing nationwide demand and made buttons more accessible for everyone. But it was bad news for river ecosystems. Mussels play a vital role in filtering water, and they serve as a food source for other animals. With the button makers in town,

DAVIS: They're quickly depleted the mussel resources by making buttons out of everybody.

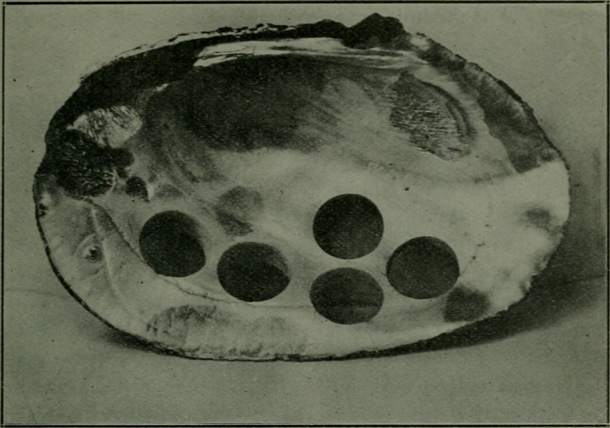

A washboard shell cut out to make five buttons in 1913. (Photo: Internet Archive Book Images, ‘Pearls and Pearlings by Herbert Harvey, Flickr)

ACKERMAN: By the early 1900's, the US button industry plowed through enough shells each year to outweigh the Statue of Liberty.

DAVIS: The ones that they didn't make buttons out of they still killed to look for pearls, because rarely there's a freshwater pearl occurs and they're beautiful. They really have unique shapes and colors to them.

ACKERMAN: Pearl hunters looking for a quick score built makeshift camps outside Northfield and other river towns. They spent entire summers scouring the river beds and prying open mussel shells. Mostly they came up empty. But Wagenbach says the process killed a lot of mussels.

WAGENBACH: The number of shells dead and dying on the banks of the river created a terrible stench, and people were really upset with the pearl hunters because it created a stench over the entire town.

ACKERMAN: Harvesting mussels for pearls and buttons did eventually wind down. One reason, with so few mussels left the odds of finding a pearl were slim to none. And by the mid 1900's, there was a new technology on the market.

CURRY: Yes, plastic.

ACKERMAN: Tierra Curry is a senior scientist with the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity,

CURRY: Buttons started to be made of plastic. And then the freshwater pearl industry kind of fell off.

ACKERMAN: Cheaper plastic buttons were even made to mimic that authentic mussel shell look. But the dawn of plastic didn't mean mussels were in the clear.

CURRY: After the button industry, the, the first really big threat was dams.

This picture shows a freshwater fishermen along the Mississippi River around the 1900s. (Photo: Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society)

ACKERMAN: Minnesota alone has about 1100 dams.

CURRY: And they reduce the amount of dissolved oxygen and they change the water temperature and the flows. And they also cut off the mussels from the host fish that they need to reproduce.

ACKERMAN: While dams muddied America's rivers, industrial pollution turned to them toxic. Curry says the Clean Water Act of the 1970's improved water quality, but it came too late for many of America's mussels. 38 species have disappeared from US waterways. That's one in every eight species that used to live here, and more are at risk today.

CURRY: Yes, it's actually really sad, 70% of freshwater mussels are at risk of extinction.

ACKERMAN: Curry fears the downward spiral of native mussels could continue. They're threatened by the effects of climate change, invasive mussels, and pesticides that trickle into streams from lawns and farms. But Curry still sees room for optimism.

CURRY: There's a lot of scientists who are very passionate about freshwater mussels. There's like this whole group of people who learn about them and are obsessed with them and start figuring out how to save them.

ACKERMAN: And many of those scientists, they're working right here in Minnesota, helping native freshwater mussels bounce back in rivers across the state.

BASCOMB: Daniel Ackerman is an environmental reporter for Minnesota Public Radio. He reported a series of stories on fresh water mussels, for links to those reports and some historical photos he put together, check out our website, LOE dot org.

Links

MPR News | “The Unnatural History of Minnesota’s Freshwater Mussels”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth