Nature in the Time of COVID-19

Air Date: Week of March 20, 2020

Self-isolating and social distancing are crucial steps to preventing the spread of the novel coronavirus, but it is still possible to connect with nature during the pandemic. (Photo: Ben.Timney, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Around the world, people are doing their part to prevent the spread of COVID-19 by staying at home. But that doesn't mean we can't take the time to connect with nature, says “Last Child in the Woods” author Richard Louv. He talks with Host Steve Curwood about the importance of nurturing our relationship to the natural world at any age, and shares some ideas about how to connect with nature in the midst of the pandemic.

Transcript

CURWOOD: In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, people around the world are doing their part to prevent the spread of the disease by staying at home and practicing social distancing when we do gather with others. So, we can’t go to the gym, the theater or out to eat but we can still go outside, at least our front or back door. And with spring in the air this may just be the perfect time to get outside. Richard Louv has authored nearly a dozen books about connecting with nature, and he is the co-founder of the Children and Nature Network. He joins us now to share his thoughts on our relationship to the natural world in the midst of this COVID-19 pandemic. Richard, welcome back to Living on Earth!

LOUV: Thanks. Nice to be back.

CURWOOD: So, where are you right now, and why?

LOUV: My wife and I live in a little town called Julian, which is east of San Diego, up in the mountains at 4,200 feet. And we moved up here to get closer to nature. And I'm glad I'm here now, we are. I mean, we've been glad. But to be able to go out the door and walk, not see very many people, see a lot of deer and wild turkeys and all of that. And that's doing a lot for our mental health right now, the fact that we can. And not everybody has that obviously.

CURWOOD: So, you are self-isolating for some reason, as well?

LOUV: Yeah, I travel a lot and I got back from a speech and my wife has some underlying lung conditions that don't bother her but they're serious enough to really, really be careful, even more than we normally would, and we would normally be quite careful. So, we're self isolating for you know, 14 days. We've got 10 days to go, but who's counting? You know, there's some folks that think this kind of response is an overreaction. But we have to be very, very careful. And hopefully that bell curve will start to reduce sooner than it otherwise would, we hope. But in the meantime, it's, as I say, I'm lucky I can step outside the door and walk for five miles.

CURWOOD: Now, the last time we spoke, we were talking about your book Our Wild Calling: How Connecting with Animals Can Transform Our Lives – and Save Theirs. What might people do during this pandemic, to connect with wildlife and how might that help us?

LOUV: I think if you are privileged, as I am, to be able to, you know, go for a walk in the forest, you know, that's a good thing. I mean, that will help your mental health, it will help your physical health. Actually, there's some evidence that it helps build immunity. And if you stay inside all the time, your vitamin D level goes down, and vitamin D deficiency is connected to all kinds of diseases. So, we have a lot of research that shows that it reduces stress, you get better mental and physical health. And also the connecting specifically with animals, whether they're, you know, the dog or the cat, if you're lucky enough to have one right now, and wild animals may also offset, I think, the downside of social distancing. We need a larger family around us, we need contact. And some of that comes from our domestic animals or companion animals. But, you know, just looking out the window and watching the woodpeckers where we live, who are quite funny. And they're kind of the bird corollary to raccoons. And I like raccoons and birds and woodpeckers. They've both got a bad attitude that I kind of admire.

CURWOOD: They certainly do.

LOUV: But that kind of connection, I think has great value, maybe even more value than normal right now.

CURWOOD: In fact, you've come up with a concept that you like to call vitamin N, meaning nature.

LOUV: Yeah, that was that's the follow-up, or one of the follow-up books to the Last Child in the Woods, which kind of introduced the idea of Nature Deficit Disorder, what happens to us when we don't get enough nature. And the research now is just really exploding. When I wrote Last Child in the Woods, there were maybe 60 studies that I could find to cite, that was 2005. Today, if you go to the Children and Nature Network website, we have a research library now. And it just recently went over 1000 studies that we have abstracts for, and they all point in the same direction, which, this is, more time spent in a natural setting improves just about everything. You know, I don't like these kind of books, the 500 things you can do, myself. But enough people asked me enough times, what can they do? And I realized a generation has gone by, maybe two generations, where this is not familiar territory. And even if you know about the health benefits, and the cognitive benefits, and you want that for your kid or for yourself, you may not know where to start. So, that book was done to answer that question.

CURWOOD: Now on the Children and Nature Network's website, you've published a list of 10 nature activities a family can do while, frankly, being sequestered during this pandemic. Tell us a little about this first one, picking a sit spot.

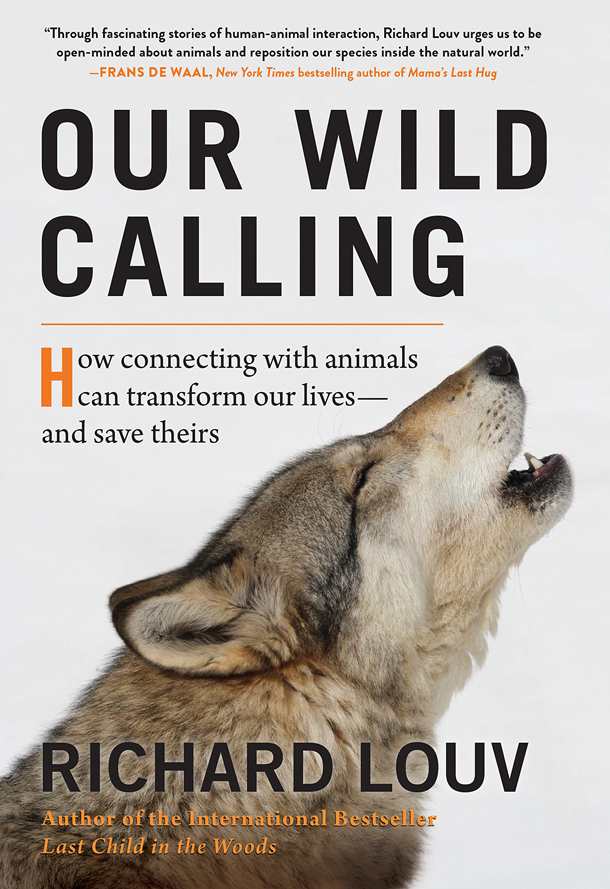

Richard Louv’s latest book, Our Wild Calling, focuses on the meaningful interactions between humans and other species as a way of combatting “species loneliness”. (Photo: Courtesy of Richard Louv)

LOUV: Well, John Young is one of the world's preeminent nature educators, and he takes hundreds of people out into the woods to learn bird language. But one of the things he recommends in a book called Coyote's Guide, that I wrote the introduction to, he advises kids and adults to find a special place in nature, it could be in your backyard. Whether it's under a tree or the end of the yard, it can be next to a creek, and he recommends you sit there for a long time. You know, know it by day, know it by night. Know it when it rains and when it snows. And he says know the birds that live there. Know the trees that live in it. Get to know these things as if they were your relatives. It seems to me that doing this can reduce our sense of isolation right now in particular. Not only the isolation that we're feeling right now because of sequestering ourselves. But this deeper loneliness that I've written about in Our Wild Calling, which is species loneliness. Our deep, deep feeling that we're alone in the universe, and we can't be. And so by sitting at a sit spot in your backyard or wherever, pretty soon you notice you're not alone in the universe. There's a lot of life around us. One of my favorites, when I was a kid, I'd go down to the creek and I'd sit next to the creek. And as you approach, all the frogs jump into the water, but then if you sit there, you know, really quiet wait for a long time, and the frogs start popping up, one after another, and you just watch them. It's, it's a lot like meditation. But I think it's even deeper in some ways than some forms of meditation. And the primary thing I think we get from that, in some strange way is not feeling as alone.

CURWOOD: Now, you're in the city, sequestered. Maybe you have a sort of three-by-three patch of dirt next to the front walk to your apartment house, a porch maybe. How do you do that?

LOUV: You know, the piece you're referring to, I posted it earlier this week. And I went back through and realized that I was reflecting way too much my own experience. I grew up at the edge of the suburbs. There are a lot of people that don't live in the suburbs, who don't get to live in Julian, up in the mountains like I do. And we've talked about this a lot at Children and Nature Network, the whole issue of equity, about the distribution of parks. I mean, you can tell people go to the park, many neighborhoods, it's quite unlikely there's a park there and if it is, you're competing with other issues. So, the idea that this kind of thing is available to everybody is is not true, but nature is everywhere. So, I went through the piece and I added quite a bit of that. You know, if you can't go outside today, set up what I call a world watching window, bring the outside in. That's finding a window view or other view. It's designed to induce our feelings of deep relaxation and awe, and vitality. Watch the birds, watch the life outside that window. Even in the densest urban neighborhoods, there are birds. Also, you can do cloud watching, you can sit inside and look at the different kinds of clouds and watch the weather go by. A couple years ago, I was visiting a guy who's head of one of the major conservation organizations. And I met his son who literally had a condition, he could not go outside, period. But he loved nature. And he talked about it a lot. And this idea of being able to see beyond the walls of your building. You can still do that. And I know that most of us would rather not be inside now but I think that that's an extraordinary important thing we can do.

Richard Louv recommends bird- or cloud-watching for those living in dense city environments. (Photo: Kim Anh, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Among the suggestions you have about connecting with nature in this time of sequesteration is to get a big load of dirt and dump it in the backyard for the kids to play in. What are you talking about?

LOUV: Well, I think that's one of my favorite ideas because it's so simple. A guy named Norman McKee, several years ago wrote me an email and he said that his kids weren't getting out in nature, he couldn't hardly get them out the front door. And he drove and he bought a load of dirt that he put in the back of his pickup and he drove home. And he dumped it in the front yard for his kids to dig in. And immediately they were outside, they were digging in it, they were making things, they were making tunnels, and roads, and he sent me a picture. It's a great picture of his little girl, three and a half, four years old. She's sitting on top of this giant hill of dirt that he had just dumped in there. She's sitting there waving her plastic bucket and her plastic shovel around her and she looks so happy. You know, sometimes these really simple things are the best things to do.

CURWOOD: One of the suggestions that you have for people to do in this time of sequesteration is to tell nature stories. How does that work?

LOUV: Well, that's something we can do all the time. But maybe that's particularly true right now. Imagination is a wonderful thing. It gets us out of our shell, it gets us out of our current reality. And we don't tell nature stories enough. Now our ancestors did, they went outside, they went into the forest and they got to hunt to bring back food, whatever it was, then they came back and they would sit around the fire with the others in their clan and they would tell stories about what happened and sometimes they would act them out with their bodies. They would dance these stories, they would become the bear. I think that much of what we see on YouTube, all those YouTube videos of animals. I went to sleep the other night while watching cat videos, by the way. It's very soothing. But I think a lot of that reflects our desire as a species, again, not to feel alone. To, to get out of our species loneliness, I hope one of the things that happens is that they begin to tell stories, they sit around the kitchen table and tell their stories. Have parents tell their stories of animals they encountered when they were kids. The kids tell the stories of what happened just the other day in the backyard when they ran into this huge grasshopper. You know, people change when they're telling those stories, their affect changes. They become very excited about life. So, now that we're having to spend more time indoors, I think that's a good thing to do is to tell these stories, and also to tell the stories about what might happen next fall. Maybe we'll go outside more next fall, or whenever this lifts. You know, we'll not only value each other more, I hope. But maybe, we'll value our larger family, the animals and plants all around us more, I hope.

Author and advocate Richard Louv has written nearly a dozen books about connecting with nature. (Photo: Eric B. Dynowski)

CURWOOD: In times like this, I think we could all do with a little hope. What do you have to offer us in terms of hope?

LOUV: By missing nature, right now and each other, this may be a way to fall in love again, with nature and with each other. I'm thinking about imaginative hope. I'm not talking about blind hope. Imagine what would the world would be like a lot of things went right, if we acted on climate change, if in fact, we set aside big areas for biodiversity, imagining a different kind of city where it's filled with biodiversity. If we begin to imagine that now, and I hope that this occurs, particularly with young people, it's a lot more likely that we will get that world than we will get the post-apocalyptic world that we're to used to imagining.

CURWOOD: Richard Louv is an author and his latest book is Our Wild Calling. Richard, thanks so much for joining us today.

LOUV: Oh, thanks. I really appreciate it.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth