March 20, 2020

Air Date: March 20, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Wildlife Trafficking and the Novel Coronavirus

View the page for this story

The illegal trade of protected species is a highly lucrative form of organized crime with deadly consequences. That’s because in addition to threatening ecosystems and inciting violence, wildlife trafficking plays a key role in spreading diseases including the novel coronavirus. Investigative journalist Lindsey Kennedy speaks with Host Steve Curwood to discuss the connections between wildlife trafficking, COVID-19 and other zoonotic diseases. (12:44)

The Next California

View the page for this story

Droughts and extreme weather are already taking a toll on the produce grown in the Central Velley of California. Now researchers from the World Wildlife Fund have found that the mid-Delta region of the Mississippi River, where rich soils currently mostly grow commodity crops like rice, corn, and soybeans, is ripe for growing more specialty crops such as fruits and vegetables. Jason Clay of WWF spoke with Host Steve Curwood about how the types of crops now grown in California could also be grown in the Mississippi mid-Delta region to enhance climate resilience and address poverty, food waste and food insecurity in America’s Heartland. (09:15)

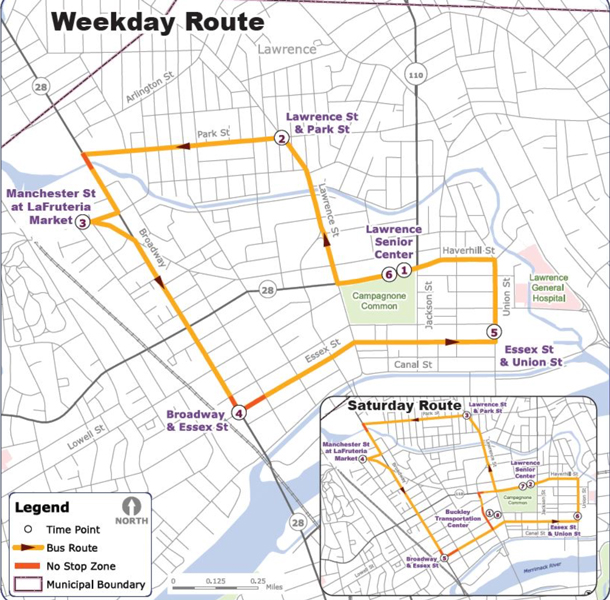

Benefits of Free Transit

/ Paloma BeltranView the page for this story

A growing trend to make public transportation free has come to Lawrence, Massachusetts, the first city in the state to provide free bus service through a pilot program. Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran reports on the environmental and social benefits of making buses free in New England’s first minority-majority city. (08:09)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s beyond the headlines roundup, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discuss the possibility of a model for the future of clean energy on the Orkney Islands off the coast of Scotland: using excess wind energy to split hydrogen from water molecules for use in fuel cells. Then the pair discuss the National Wildlife Federation’s endorsement of Democratic Presidential nominee candidate Joe Biden, as well as the 25th anniversary of the reintroduction of wolves into Yellowstone National Park. (04:03)

Nature in the Time of COVID-19

View the page for this story

Around the world, people are doing their part to prevent the spread of COVID-19 by staying at home. But that doesn't mean we can't take the time to connect with nature, says “Last Child in the Woods” author Richard Louv. He talks with Host Steve Curwood about the importance of nurturing our relationship to the natural world at any age, and shares some ideas about how to connect with nature in the midst of the pandemic. (12:46)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jason Clay, Lindsey Kennedy, Richard Louv

REPORTERS: Paloma Beltran, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX– this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

You can probably blame the illegal trade in wild animals for sparking the novel Coronavirus pandemic.

KENNEDY: We don't know exactly how that virus moved. But what we do know is that when you bring wild animals into contact with humans and livestock, you massively increase the risk of all these different diseases, jumping between species and going into the human population and just causing havoc.

CURWOOD: Also, a bid for free public transit in the US.

WU: So free public transportation is really about recognizing that we need to invest in the public good to match our big picture urgent challenges, as we struggle with climate vulnerability and traffic and an increasing housing crisis that is pushing people further and further away from job centers.

CURWOOD: We have those stories this week, on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Wildlife Trafficking and the Novel Coronavirus

Illegally trafficked pangolin scales seized by the Hong Kong Customs & Excise Department (Photo: Alex Hofford, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The novel corona virus pandemic is calling attention once again to the illegal trade of endangered species. This latest virus likely jumped from bats to endangered pangolins and then to humans at a so-called wet market for bush meat in Wuhan, China. Three quarters of new human diseases come from animals, such as Ebola, SARS and HIV, and these are zoonotic diseases and wildlife trafficking plays a key role. It’s one of the most lucrative and devastating forms of organized crime and it has led to the dramatic decline of many species, including rhinos, elephants, and pangolins. Investigative journalist Lindsey Kennedy recently wrote about this for Foreign Policy magazine and joins us now from Glasgow, Scotland. Lindsey Kennedy, welcome to Living on Earth!

KENNEDY: Thank you very much. Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So why do you study zoonotic diseases?

KENNEDY: Well, I don't specifically study the diseases. I'm part of a journalistic collective. And I have spent the last two years my colleague Nathan Southern, looking into the wildlife trade in Southeast Asia. And I think a lot of people don't realize how big the wildlife trafficking trade is. It's one of the four biggest illegal trades in the world. It brings in about $26 billion a year. And most of that goes back to China. But the most trafficked mammal in the world is an animal called the pangolin. That kinda looks like a small scaly anteater. And about 10,000 of these are trafficked every year. So when we saw that carcasses of the pangolin, on their way into China, illegally being trafficked, had tested positive for the COVID-19 virus, we started thinking about whether or not this could have been something that triggered the outbreak. So we came at it from a wildlife perspective rather than a disease studies perspective.

A colony of bats in Battambang, Northern Cambodia. Bats can carry many zoonotic diseases, including the coronavirus. (Photo: Lindsey Kennedy)

CURWOOD: So explain to me how the pangolin might be related to COVID-19.

KENNEDY: So when any kind of disease can jump from a species to another species or an animal to a human, that's called a zoonotic disease. And that's incredibly dangerous because our immune systems aren't prepared to deal with them. In the case of COVID-19, we know that came from wild animals. It's present in bats and pangolins, and snakes. We don't know exactly which of these animals were provided the link to humans; all of them are trafficked and sold within China. And we don't know exactly how that virus moved. But what we do know is that when you bring wild animals into contact with humans and livestock, you massively increase the risk of all these different diseases, jumping between species and going into the human population and just causing havoc.

CURWOOD: And remind us of other diseases that are zoonotic, that come from animals and jumped to humans.

KENNEDY: Well SARS is another one that originated in civet cats, actually, back in 2003 in China, and that was a very similar thingl that was wildlife being sold in markets and that's where it originated. Ebola is another one that comes from bats. Similar to COVID-19, again. There's just loads of them to be honest: Bird flu, swine flu, these are these are all zoonotic diseases.

Pangolins are the most trafficked mammal in the world. It is thought that pangolins may have spread the coronavirus to humans. (Photo: Adam Tusk, Flickr, CC-BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: In fact, isn't HIV zoonotic?

KENNEDY: Yes, it is. Yeah.

CURWOOD: And to what extent are these diseases getting into the human population, because we're destroying habitat of these creatures and consuming more and more?

KENNEDY: It's definitely creating more and more risk all the time. Because the more you have deforestation, the more humans go further into the habitats of animals. And they're coming into contact with animals they haven't done so with before. And every creature on earth carries like millions of types of bacteria and virus. So every time you come into contact with a new animal, you just increase this risk massively. And epidemiologists have been saying for some time that the more contact we have with animals through deforestation, or by going into forests and bring animals back into our world and selling them and markets and that kind of thing, i t's been predicted for a while that there would be a pandemic. We just didn't know when it was going to happen. And now we're seeing it happen.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about About the markets where these animals are sold, I guess you call them wet markets. Well, what do they look like?

KENNEDY: Well, actually, it depends on where you are in the world because they're not just in China. But generally, if you just imagine like a big sprawling market where it's not necessarily the cleanest, but you've got lots of live animals squashed into small spaces in cages, different types of animals in small spaces, and sometimes you've got animals being sort of cut up and prepared for sale, even while you've got live animals still nearby. And if you just think about when meat is prepared in factories, how clean that has to be and how many processes an item goes through on a production line to make sure that a virus or a bacteria doesn't jump from one to another. And none of that is happening in a market, in a big wet market like that. Just people are walking around, they're touching different bits of meat. People are sneezing, animals are touching each other. It's just chaos, really, in terms of virus prevention.

CURWOOD: Not very appetizing, eh?

Koh Kong Conservation Corridor, home of the critically endangered Sunda Pangolin. (Photo: Lindsey Kennedy)

KENNEDY: No, not really.

CURWOOD: So why is it the people eat food, eat things, that are in these kind of conditions?

KENNEDY: In the case of China, actually most wildlife that's trafficked is done so for traditional Chinese medicine. So like the pangolin, the example I gave you before, that's an animal that's used in lots of different types of Chinese medicine; Also, its scales are using the production of meth. Parts of tiger and rhino are used in Chinese medicine. So that's why these kinds of products are brought in and sold in markets. But a lot of animals also sold just for meats, just because it's kind of a prestige thing to eat wild meat and a lot of the world.

CURWOOD: Indeed something I don't quite understand. But, you know,

KENNEDY: I can't say I do either to be honest.

CURWOOD: Different strokes for different folks. Now, what step has China and other countries taken in terms of regulating the wildlife trade, now that we've seen yet another instance of how deadly this can be for humans.

KENNEDY: It is illegal in China to import endangered animals. It has been for some time. There's a few problems with this. The big one is the fact that all efforts to kind of stop the trade have focused on prosecution haven't done anything to tackle demand at all over the years. And so the trade hasn't really reduced, because it doesn't matter how many poachers you send to prison. And it doesn't really matter how many busts of shipments coming into China you make. If people still want to buy those things, someone's going to find a way to get them in. And the thing about this particular scenario with the coronavirus outbreak is that a lot of conservationists are hoping that this is going to be more effective than any of that regulation because people will be put off eating it and they'll stop buying it in case they get sick. So hopefully this situation will actually be more effective than regulation has been in the past.

CURWOOD: What regulations has China put on it right now? Anything specific in the wake of the coronavirus outbreak?

The coronavirus originated in a Chinese wet market, where animals of all types are sold in close proximity. (Photo: Daniel Case, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA)

KENNEDY: Yeah, there has been a ban put in on selling wildlife in the markets. They did the same thing after SARS, though. So it remains to be seen how long that lasts and whether it's just until it all blows over and then it comes back. So, again, if people want it enough, it'll come back; if people decide that actually it's not healthy for them, hopefully that will stop happening. I mean, the younger people in Southeast Asia and in China aren't as interested in eating and wildlife. They don't see it so much as like a social status. It's something sort of like the weird older people do. So hopefully, over time, as these people grow up, they'll maintain those attitudes; you have to hope.

CURWOOD: So, looking back, Lindsey, what did we learn from the response to SARS and that that had jumped from animals. And from that lesson, what can we do now to perhaps better prevent another outbreak?

KENNEDY: Um, I think with SARS, it was contained relatively quickly. And I'm not a clinician; I don't specialize in epidemics. But SARS was contained relatively quickly and I think we kind of got away with it. And for that reason, there wasn't a sea change. And people kind of forgot about it. They started doing the same things, buying the same animals after a little while, and think maybe it was seen as a bit of a one off. Whereas this time, I think, I don't think anyone realize how far this would spread. I mean, we've declared a global pandemic; it's, it's huge. I think that that has to leave lasting changes; that has to leave lasting attitudes towards eating wildlife and tracking wildlife this time.

CURWOOD: This highly lucrative traffic, and poaching and hunting and dangerous species goes on, as you say, at a very high level, there is a huge market. How can it be stopped? How could it be stopped?

Lindsey Kennedy is an investigative journalist who has studied the wildlife trafficking trade in Southeast Asia. (Photo: Lindsey Kennedy)

KENNEDY: The only way you can stop the illegal wildlife trade is by reducing demand, everything else makes it worse. There's an amazing writer on conservation, Vanda Felbab Brown, who uses this example of being a bit like the drug trade, where let's say you're bringing in a massive shipment of cocaine into a country. You know that the border control is going to seize it's like 50% of that. So you just get, you know, your producers to give you 50% more cocaine in the first place. And the problem is, is when you apply that to animals, like when you pass the wildlife trafficking trade, that's incredibly destructive, because if you kill another 50% of pangolins, or tigers, you might be punishing more people. But you're killing more animals as a result. So really, it has to be an education thing, where you persuade people not to buy it and you also need to remember that the people who are poaching are often incredibly dire situations or, you know, really poor areas where there are a few employment opportunities. So you have to treat it as a development issue as well and work with those people to provide better employment so that they're not tempted to go and poach something on spec, basically,

CURWOOD: What can the international community do to stop this? What has it done so far? And where are the deficits and the approach?

KENNEDY: One kind of more popular angle that's been floated a lot by people trying to fight the trade is to treat the wildlife trade as a serious organized crime problem. And sometimes a something that's used to fund terrorism. And to really push that angle because that attracts funding, right? That really gets government's attention. If you say this is a massive organized crime thing, and these people might be using it to fund terror as well, you know, grabs attention. But the problem is, is then you start reacting to it with police and with armies. And those things don't, again, they don't stop someone in China wanting some little old lady that wants to go and buy like her Chinese medicine stuff in China, it doesn't stop her. It doesn't stop the poacher in the Namibia, who wants to feed his family, it doesn't stop either of those things. So even though there's been loads more money thrown at this in recent years, and even though people are taking it very seriously, governments and taking it very seriously, they're kind of just going about it in the wrong way, and it's making it worse. I mean, it doesn't help that in the US, you know, a couple of years ago, Trump lifted the ban on importing elephant products, I mean, which I'm sure has nothing to do with the fact that his own sons a big trophy hunters abroad, which has, you know, helped to react against a lot of change has been made in people's opinions about whether it's appropriate to hunt animals. But as I say, they're really effective policies are the ones that work with local communities, help people to shift from poaching to sustainable tourism, and going and seeing the wildlife you know, going out and photographing wildlife instead of killing it and that kind of thing. They've been effective and educating people about why it's damaging to the environment and to themselves to eat wildlife. These are the effective things but not so much going in all guns blazing and arresting people.

CURWOOD: We're talking about covert 19 today and the understanding that this came to humans from animals that were being trafficked and sold in markets. But talk to me about the broad implications of wildlife trafficking.

KENNEDY: Yeah, we are losing species across the globe faster than at any other time since the dinosaurs. It is kind of an emergency, really the rate at which we're losing biodiversity. And that is driven by wildlife trafficking and deforestation. And that's just a tragedy in itself to lose that incredible wealth of ecology. But it is also a tragedy for the human societies that live in these areas in places like Indonesia. And when you look up the island of Borneo, communities have lived in the same way for hundreds of years. Some people will live on the fringes of forests, they hunt food in a way that is sustainable, or they fish or they're able to build their homes from trees in that area without doing serious damage. But when you have wholesale destruction of an area, you just completely disrupt all of the ways those people live and you push them further into poverty. And it's so it's just a tragedy kind of all across the board, really.

CURWOOD: Lindsey Kennedy, investigative reporter, thank you so much for taking time with us today.

KENNEDY: Thank you.

Related links:

- Foreign Policy | “The Coronavirus Could Finally Kill the Wildlife Trade”

- Living on Earth’s interview with the Center for Biological Diversity’s Sarah Uhlemann on Pangolins and the wildlife trafficking trade

[MUSIC: Balval, “Molin Molette” on Le Ciel Tout Nu, by Rosalie Hartog, Whaling City Sound]

CURWOOD: Coming up- Diversifying beyond the central valley of California for fruit and vegetable production. That's just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Balval, “Molin Molette” on Le Ciel Tout Nu, by Rosalie Hartog, Whaling City Sound]

The Next California

WWFUS hopes that a research-based pilot project could demonstrate the best crops to grow in the mid delta Mississippi region, in order to manage the most efficient transition for all stakeholders (Photo © Julia Kurnik, World Wildlife Fund)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

When you take a juicy bite out of a honeydew melon or chomp down on a handful of almonds, chances are that food came from the central valley of California. This region has perhaps the world’s largest patch of class one soil, with abundant sunlight and no winter snow. But as the climate has changed, the flow of water from the Sierra Mountains has become less reliable. There have also been more heat waves and choking smoke from wildfires. So scientists and economists from the World Wildlife fund are Next California dreamin’. They say the Mid-Mississippi river delta region is ripe for a switch from commodity crops such as cotton, rice and soy, to more high value specialty crops such as fruits and vegetables. For more on the plan they call, “The Next California” I’m joined by one of its co-authors Jason Clay, Senior Vice President of Markets at World Wildlife Fund US. Jason, welcome to Living on Earth.

CLAY: Thank you. Nice to be here.

CURWOOD: So how did you get into this study of farming and food?

CLAY: Wow. Well, I actually grew up on a farm, a very small farm in northern Missouri. And we lived on less than $1 a day. And so, as you might imagine, I couldn't get away from farming fast enough. But everything I've done in my life has kind of led me back to farming. And about 20 years ago or so I started to work with WWF and convince them that, in fact, the biggest threat to the planet to biodiversity to ecosystem services is where and how we produce food. And from that point on, we begin to develop a program around agriculture around livestock around aquaculture, seafood. And so I've been working on that since then.

The plan hopes to engage smaller scale farmers, those who could most benefit from specialty crops with higher per-acre value than commodity crops. (Photo © Julia Kurnik, World Wildlife Fund)

CURWOOD: So Jason, what's the importance of California to our food systems?

CLAY: For the last hundred years or so California has become the major source of the fresh food that we eat. About a third of all vegetables about two thirds of the fruits and nuts all come from California. So, almonds and pistachios and things like that, but also cling peaches and olives and Kiwi and honeydew. California is just very important to the food system. 100 years ago it wasn't, but it is today.

CURWOOD: I'm getting hungry, just listening to list all those things so you can get from California. What are some of the risks to this system? Looking ahead?

CLAY: Well, it's actually not even looking ahead we're already seeing that California is being affected by droughts by fires by freezes late in the spring, but also by winters that are too warm to actually allow the fruit trees to bloom well and have a good, a good crop the next year, we're seeing low or at least below normal snowfall, in the mountains. And then in the summer, the snow melts too fast so that we don't have enough water all year round to irrigate the crops. We're losing at least the last of four crops and maybe the last two, depending on where you are and what year it is. So California is being affected by climate change already. This is happening all over the country, but we're not as dependent on the other parts of the country as we are California.

CURWOOD: So I understand that you and your colleagues at the World Wildlife Fund have just released a report that identifies the potential of the Mississippi River mid-Delta region, that's near Memphis, as I understand it, as perhaps an agricultural engine for fruits and vegetables. You're calling it the next California plan, give me a little context of it.

Newer farming methods such as hoops could extend the growing season in the mid-delta, which might prove critical to the plan’s success. (Photo © Julia Kurnik, World Wildlife Fund)

CLAY: So if we're not going to be able to rely on California for the same quantities and range of fruits and vegetables that we've been getting from there, the question is, where are we going to get them from? And when we started asking this, we began to realize that the mid-Delta region, which is kind of most of Eastern Arkansas, Southeast Missouri, Western Tennessee and northwest Mississippi, that area actually has about the same amount of land in production as California does. California has about three quarters of the land in specialty crops. And in this area in the mid-Delta, it's only about a quarter. So there's a lot of room to expand production there. But this is an ideal place to see, you know, could we actually begin to shift production in a logical, organized way into this region without major disruptions in the food system? Because if we can anticipate this change, we can can make it happen much more smoothly, much more efficiently and a lot cheaper without the crisis that would come with trying to replace California overnight.

CURWOOD: But tell me, Jason, that area, the Mississippi Delta is well it's kind of hot and humid sometimes. I mean, California's drier and how are these specialty crops? How are fruits and vegetables going to do in a place like that?

CLAY: So that's exactly what we're looking at right now, which crops of all those grown in California could be grown in this region, and which ones would actually do better in this region than they do in California. In this area, the problem is not lack of water. In fact, there's plenty of water, and there's a lot of rainfall. And as you noted, there's a lot of humidity. There's also a lot of heat at night. And all those things affect the types of crops that you can actually grow. But fruit trees, for example, which require cold winters are perfect for this area. In fact, they're better than in California. There's also the fact that in this region, there's a lot of poverty, a lot of unemployment. And so the labor issue is not potentially as much of a problem as it is in California. But the biggest thing from the point of view of profitability is that the cost of land in the region in the mid-delta is about 20% of what it is in California. But California is not going to stop producing the things that it produces well, but the more water intensive crops, the lower value crops, those are the ones that are probably going to go. We think some could be picked up in the mid Delta. But going forward, we might have a more distributed food system. Before California, food was produced in New Jersey and Ohio and Michigan and various places, all you know, during the summer months when they could grow and it was canned for the rest of the year. Now we expect fresh and so it's a different kind of system. But we're probably going to get back to a much more distributed food system with the impacts of climate change. But if we're if we're thinking about producing food in different places, we can also think about different systems to, of infrastructure to actually distribute the food. One of the things that struck me about farming in the Midwest is that most of the farming areas are actually food deserts.

Compared to the central valley of California, water and rainfall are much more plentiful in the floodplains and rolling hills of the mid-Delta Region (Photo © Julia Kurnik, World Wildlife Fund)

CURWOOD: Really?

CLAY: Because they don't have access to fresh food all year round. And this is no exception. In fact, people in the mid-Delta region are like number 49 or 50, in terms of some of the states that eat the fewest fresh fruits and fresh vegetables.

CURWOOD: Jason, some folks point out that we waste about a third of our food. Some of it, you know, becomes science experiments in the back of our refrigerators if we've gone out to eat. Others are back in the distribution system that never make it to market. How would the next California plan address the issue of food waste, do you think?

Irrigation is a major concern for many farmers, and they will have to adapt as the weather becomes increasingly unpredictable (Photo © Julia Kurnik, World Wildlife Fund)

CLAY: Well, I think that food waste is a huge issue. In developed countries, it tends to be more the food that we waste on our plates and in restaurants. But in developing countries, it's more about post harvest losses and storage and diseases and pests and rodents and all kinds of things that that destroy food, but it does come to 35 to 40% of all the food in every country. What the 'Next California' does is reduces the transportation involved in food. It increases the quality of food on the shelf by having it more local. And it increases the time that it's on the shelf, we can really take advantage of how close this region is to Chicago and St. Louis and Kansas City in New Orleans and even through the intercostal canal up to the east coast. And so those things all should reduce food waste, but it's got to be about handling and about consumer awareness that we do these things as well because food waste is almost a way of life now. It's we're a throwaway society and we throw away a lot of food. Food doesn't have the value that it needs to have for us to think of it as precious.

CURWOOD: Jason Clay is a senior vice president of markets at World Wildlife Fund US and helped write the proposal called 'The Next California: Phase One', Jason thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

CLAY: Thank you. It was a real pleasure.

CURWOOD: For more on how northwestern Mississippi and nearby Arkansas could shift away from cotton, soy, corn and toward more fresh fruits and vegetables, go to the Living on Earth website, loe.org. There you can see the World Wildlife Fund suggestions for the next California.

Related links:

- Read the WWFUS ‘Next California’ report here

- Click here to learn more about the threat our changing climate poses to California’s ability to supply food to the country

- Read more about food system resilience

- Click here to learn about the work of WWF’s Markets Institute

[MUSIC: Luther “Guitar Junior” Johnson, “Ramblin’ Blues” on Talkin’ About Soul, by Luther Johnson, Jr., Telarc Blues]

Benefits of Free Transit

People aboard the 85 bus route in Lawrence on their way to doctor’s appointments, classes and groceries. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb, Living on Earth)

CURWOOD: In first half of the twentieth Century, Lawrence, Massachusetts was one of the world’s largest producers of textiles, thanks to the waterpower of the Merrimack River and the hard labor of immigrant factory workers. Musical giant composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein was born in Lawrence to immigrant parents from the Ukraine, a few years after the famous Bread and Roses strike in 1912 helped to ignite the American labor movement. Today, Lawrence is still largely a community of immigrants, though more Spanish is heard there today than Ukrainian, and it’s still on the cutting edge of the quest for social justice. This time it’s a move to better the lives of all residents with a trial of free local public transit to lower polluting emissions and help the disadvantaged. Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran has our report.

[BUS SOUNDS]

BELTRAN: The 85 bus pulls up in front of the Senior Center in Lawrence, Massachusetts.

[SOUNDS OF BUS PULLING UP]

BELTRAN: Two elderly women take seats next to the window, behind the bus driver.

[SPANISH CHATTING]

BELTRAN: They are each carrying oversized purses and chat in rapid Spanish, catching up on their families, proudly talking about grandchildren.

[SPANISH CHATTING]

BELTRAN: These ladies have been riding the bus like this for years but one thing recently changed for them - now it’s free. The City of Lawrence is offering free bus service for three bus lines for the next two years. And for a community where nearly a quarter of the residents live below the poverty line, that can make a big difference. A rider named Diane sits towards the front of the bus. Petite with blonde hair, Diane says she rides the bus about 3 days a week...

DIANE: To go to a soup kitchen. Or just to take me to close places that I need to go.

BELTRAN: And what do you think of the fact that it's free?

DIANE: Oh, it's awesome, real good. I sometimes don't even have the money to walk in the cold. So the free bus really helps out a lot.

Reporter Paloma Beltran speaks with Luis who has been a bus driver with the Merrimack Valley Transit Authority for 26 years. He forms part of the Lawrence community and has seen new riders riding the bus after the free bus program began. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb, Living on Earth)

BELTRAN: Many Lawrence residents are recent immigrants like Vinicio. He moved here from the Dominican Republic 5 years ago. He likes the new-free fare program.

[SPANISH]

VINICIO: It’s very good for the poor because sometimes we don’t have the $1.25 for the bus. And this is very efficient. I hope that they keep this because the poor need help.

[BUS SOUNDS]

BELTRAN: A college student named Rosielis sits with a backpack full of textbooks. She is looking out the window, as the bus passes bodegas and the endless red brick buildings.

ROSIELIS: I take it daily because I have classes every day so I had to take from Monday to Friday, sometimes weekends when I had to do errands and stuff. And I had to save that like at least $25. So I will have enough money for it to come from school, and to school.

BELTRAN: Surveys show that most of the riders in the free bus program make less than 20,000 dollars a year. And since the program started, ridership has gone up about 20% percent.

RIVERA: I think that I get two reactions, one that people are happy. And two is when are we going to expand it?

BELTRAN: Lawrence Mayor Dan Rivera was a key driver behind the city’s free bus program. He says it’s a way to help low income residents.

RIVERA: You give people the ways to go make a good living, or go to school or go to the doctor's office or do all those things without worrying about having a car. With a very small infusion of funds you can give people a decent amount of relief in their wallet.

Route 37 forms part of the Lawrence free bus program and it passes by the Lawrence Technical School. (Photo: Paloma Beltran, Living on Earth)

BELTRAN: Indeed, only 5 percent of the operating cost for the bus in Lawrence actually comes from fares collected. So to launch this pilot project, Mayor Rivera asked the City Council to allocate $225,000 to make up the shortfall for offering the service for free. At this point Lawrence only offers free fares on three bus lines, those that stay within the city limits. But Lawrence is far from alone in this; free transit is a growing trend. Olympia, Washington recently joined Lawrence with a much larger free transit system throughout the city. And fifty miles south of Lawrence, in Boston, there are plans for a controversial new 1 billion dollar fare collection system. But Boston City Council member Michelle Wu says that free public transportation would be a better investment.

WU: The way to close gaps around the racial wealth divide around income inequality is to connect people where they need to go without financial barriers.

BELTRAN: A free bus program in a city like Boston would cost on the order of 100 million dollars according to Boston Mayor, Marty Walsh, a price he says the city simply can’t afford. But proponents including Michelle Wu say the cost would be closer to 30 million dollars and that money could be made up with a 2 to 3 cent increase in the gas tax. And she says free bus fare is a simple way to improve people's lives and help the environment.

WU: So free public transportation is really and in particular free bus service across various cities, is really about recognizing that we need to invest in the public good to match our big picture urgent challenges, as we struggle with climate vulnerability and traffic and an increasing housing crisis that is pushing people further and further away from job centers.

BELTRAN: Emissions from traffic are on the rise in Boston and it routinely has some of the worst urban congestion in the country, number one in traffic according to a recent study. And Boston sits at sea level, making it particularly vulnerable to the threats of climate change and sea level rise. Michelle Wu sees public transportation at the nexus of addressing those long-term concerns and improving public health more immediately.

The 85 bus route forms part of the the Lawrence free bus program and passes by the Lawrence Senior Center allowing Seniors to gain more mobility through the city. (Photo: MVRTA)

WU: We are at a time in our city, state, country, planet's history that's really significant. And we're right at the edge of staring down a climate crisis. But even just in the moment today, the kids that we're sending out on the basketball courts are exponentially increasing their chances of living a healthier life, if we can help make sure that they're breathing in clean air.

[BUS SOUNDS]

BELTRAN: Back on the 85 bus in Lawrence. Two children walk to the very end of the bus. The older sister grabs her brother’s backpack as she guides him to sit next to her. They are very aware of the free bus and what a help it has been for their family.

CHILDREN: It shows that the bus is really useful. And it's kinda, it's kind of better to not pay because then it leaves us with extra money for the bills of our houses and the gas, laundry and all the money that we need for clothes and food.

BELTRAN: The little brother dangles his feet from the edge of the bus seat.

CHILDREN: So free bus is for like there's people who are who they they don't have money. Or some people don't have families. They have to get a free bus because if they don't have money, how are they going to pay?

BELTRAN: Lawrence is a city of immigrants, new arrivals in this country. And the notion of offering free bus service is also a new concept here. But roughly 100 cities in Europe have been experimenting with free transportation for nearly a decade. All betting that a free ride will help both the poor and the environment.

For Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran in Lawrence, Massachusetts.

Related links:

- Boston Globe | "‘Just Make It Free’: Lawrence Paid All the Fares for Three Bus Routes, and Ridership is Up"

- The New York Times | "Should Public Transit Be Free? More Cities Say, Why Not?"

- Huffpost | "Here’s What Happens When Public Transit is Free"

[MUSIC: Wilfrido Vargas, “El Africano” on El Funcionario, Karen]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Some remedies for cabin fever in these times of self-isolation. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Maná, “No te rindas ( Maná cover ) Instrumental version by Inka Gold”]

Beyond the Headlines

Millions of Grey seals and Common seals (like the one pictured) breed each year on the Orkney islands. (Photo: Charles J. Sharp, Sharp Photography, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

It's time to take a look beyond the headlines now with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with environmental health news thats ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. He's on the line now from Atlanta. Hi there, Peter. How you doing? What do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, I'll tell you what I don't have Steve. I'm not going to talk about the corona virus because I think we're all hearing enough. It's a very important story, but I'd rather give you a smaller story that's kind of good news.

CURWOOD: Oh, good. And I'm glad you don't have the corona virus. What's your good news?

15% of the world’s grey seals breed on the Orkneys, but the islands are also a breeding ground for clean energy, and the excess wind power is now being used to split hydrogen off of water molecules for use in hydrogen fuel cells. (Photo: Claire Pegrum, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: The Orkney Islands north of Scotland. 22,000 people up to 15% of the world's seal population during breeding season, and they produce more clean energy, specifically wind power than those 22,000 people and millions of seals can use. So they're taking the excess power which they can't ship to the mainland because they have an antiquated power grid and power cables that can handle the load. And so what they do with that excess power, is they use it to convert water into hydrogen and oxygen atoms, and they use the hydrogen to make fuel cells.

CURWOOD: And what are they using the fuel cells for?

DYKSTRA: One project that's underway is using hydrogen fuel cells to power a ship that carries supplies back and forth between the Orkneys and Scotland. The usual way that the hydrogen is supplied for fuel cells in large scale projects involves using fossil fuels. That's hardly a step ahead for clean energy.

CURWOOD: That's right. Hey, what else do you have for us today?

The National Wildlife Federation, a relatively moderate large conservation organization, has endorsed Joe Biden for President of the United States (Photo: National Wildlife Federation, Fair Use)

DYKSTRA: A little politics. Most large conservation groups if they've made an endorsement, have endorsed Bernie Sanders, thanks mostly to the Green New Deal. But Joe Biden grabbed the endorsement of the National Wildlife Federation, arguably the most politically moderate of the big conservation groups.

CURWOOD: And Joe Biden, I don't think is hostile to greens but he doesn't have exactly the greenest reputation does he?

BASCOMB: The League of Conservation Voters gave him a lifetime score of 83%. Now most democrats are pulling a little bit higher than that these days. Certainly that's the case with Bernie Sanders and the former candidate Elizabeth Warren. But the NWF is a group with a large hunting component. They're more politically diverse, more politically moderate than groups like the Sierra Club, for example.

CURWOOD: And of course, Joe Biden's legal Conservation Voters scored dates from well know what a couple of decades ago.

The League of Conservation voters has given Joe Biden a lifetime score of 83% for his voting record in the US Senate. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC by SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Back to the 1980s Yeah.

CURWOOD: Hey, what do you have from the history vaults for us this week,

DYKSTRA: March 21, 1995, was one of the key dates in which gray wolves were released in Yellowstone National Park. The first release actually came a few months before that in January, but this year marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of what has so far turned out to be a very successful relocation of wolves into Yellowstone.

CURWOOD: So what are the numbers?

Yellowstone’s Grey Wolf population has expanded to around 95 wolves inside the park, and as many as five times more in the area outside the park, since their reintroduction 25 years ago. (Photo: Steve Harris, Flickr, (CC BY-NC 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Right now there are about 100 wolves in the park, but a much larger number than that maybe as many as 400 or 500 have gone outside the park boundaries, looking for their own territory. Of course, wolves are very territorial. And so the Greater Yellowstone wolf population is now easily the biggest wolf population in the lower 48 states.

CURWOOD: I imagine the ranchers still don't like them though, huh.

DYKSTRA: The ranchers don't, they say they're predators on livestock, particularly sheep, but it's been 25 years, the project seems to be a success on all sides, and the ranchers have not exactly gone out of business over it.

The greater Yellowstone region now has more Grey Wolves than anywhere else in the lower 48 states. (Photo: Dark_muse, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, thank you. Peter. Peter Dykstra's is an editor with environmental health news that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve. Thanks a lot, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: There's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- CNN Business | “This Small Island Chain Is Leading the Way on Hydrogen Power”

- The Washington Post |“Joe Biden Nabs Endorsement From National Wildlife Federation’s Political Arm in First for the Group”

- Click here to learn about Grey Wolves

- Read about the history of wolf reintroduction into Yellowstone National Park, and some of the controversy surrounding the project

[MUSIC: Liz Story, “Rumors Of Discipline” on 17 Seconds To Anywhere, by Liz Story, Windham Hill Records]

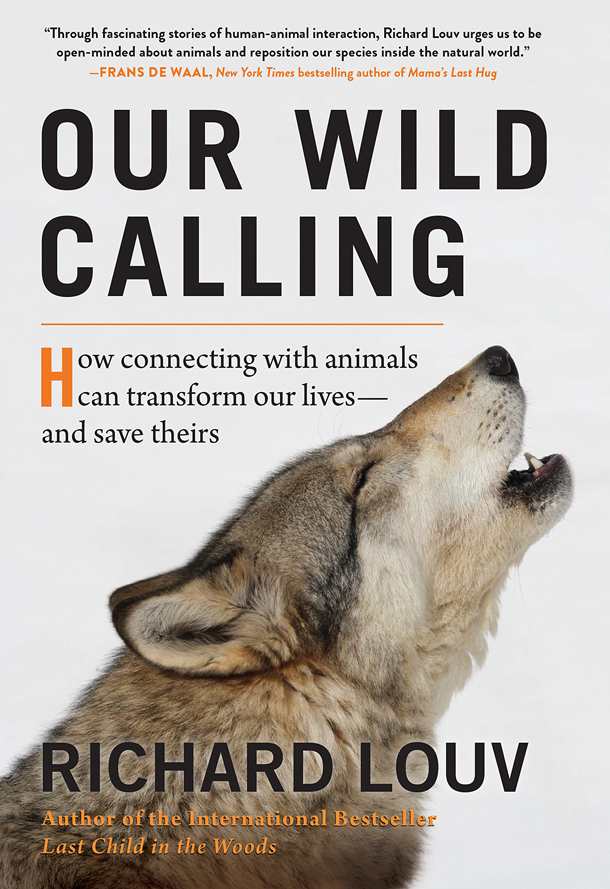

Nature in the Time of COVID-19

Self-isolating and social distancing are crucial steps to preventing the spread of the novel coronavirus, but it is still possible to connect with nature during the pandemic. (Photo: Ben.Timney, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, people around the world are doing their part to prevent the spread of the disease by staying at home and practicing social distancing when we do gather with others. So, we can’t go to the gym, the theater or out to eat but we can still go outside, at least our front or back door. And with spring in the air this may just be the perfect time to get outside. Richard Louv has authored nearly a dozen books about connecting with nature, and he is the co-founder of the Children and Nature Network. He joins us now to share his thoughts on our relationship to the natural world in the midst of this COVID-19 pandemic. Richard, welcome back to Living on Earth!

LOUV: Thanks. Nice to be back.

CURWOOD: So, where are you right now, and why?

LOUV: My wife and I live in a little town called Julian, which is east of San Diego, up in the mountains at 4,200 feet. And we moved up here to get closer to nature. And I'm glad I'm here now, we are. I mean, we've been glad. But to be able to go out the door and walk, not see very many people, see a lot of deer and wild turkeys and all of that. And that's doing a lot for our mental health right now, the fact that we can. And not everybody has that obviously.

CURWOOD: So, you are self-isolating for some reason, as well?

LOUV: Yeah, I travel a lot and I got back from a speech and my wife has some underlying lung conditions that don't bother her but they're serious enough to really, really be careful, even more than we normally would, and we would normally be quite careful. So, we're self isolating for you know, 14 days. We've got 10 days to go, but who's counting? You know, there's some folks that think this kind of response is an overreaction. But we have to be very, very careful. And hopefully that bell curve will start to reduce sooner than it otherwise would, we hope. But in the meantime, it's, as I say, I'm lucky I can step outside the door and walk for five miles.

CURWOOD: Now, the last time we spoke, we were talking about your book Our Wild Calling: How Connecting with Animals Can Transform Our Lives – and Save Theirs. What might people do during this pandemic, to connect with wildlife and how might that help us?

LOUV: I think if you are privileged, as I am, to be able to, you know, go for a walk in the forest, you know, that's a good thing. I mean, that will help your mental health, it will help your physical health. Actually, there's some evidence that it helps build immunity. And if you stay inside all the time, your vitamin D level goes down, and vitamin D deficiency is connected to all kinds of diseases. So, we have a lot of research that shows that it reduces stress, you get better mental and physical health. And also the connecting specifically with animals, whether they're, you know, the dog or the cat, if you're lucky enough to have one right now, and wild animals may also offset, I think, the downside of social distancing. We need a larger family around us, we need contact. And some of that comes from our domestic animals or companion animals. But, you know, just looking out the window and watching the woodpeckers where we live, who are quite funny. And they're kind of the bird corollary to raccoons. And I like raccoons and birds and woodpeckers. They've both got a bad attitude that I kind of admire.

CURWOOD: They certainly do.

LOUV: But that kind of connection, I think has great value, maybe even more value than normal right now.

CURWOOD: In fact, you've come up with a concept that you like to call vitamin N, meaning nature.

LOUV: Yeah, that was that's the follow-up, or one of the follow-up books to the Last Child in the Woods, which kind of introduced the idea of Nature Deficit Disorder, what happens to us when we don't get enough nature. And the research now is just really exploding. When I wrote Last Child in the Woods, there were maybe 60 studies that I could find to cite, that was 2005. Today, if you go to the Children and Nature Network website, we have a research library now. And it just recently went over 1000 studies that we have abstracts for, and they all point in the same direction, which, this is, more time spent in a natural setting improves just about everything. You know, I don't like these kind of books, the 500 things you can do, myself. But enough people asked me enough times, what can they do? And I realized a generation has gone by, maybe two generations, where this is not familiar territory. And even if you know about the health benefits, and the cognitive benefits, and you want that for your kid or for yourself, you may not know where to start. So, that book was done to answer that question.

CURWOOD: Now on the Children and Nature Network's website, you've published a list of 10 nature activities a family can do while, frankly, being sequestered during this pandemic. Tell us a little about this first one, picking a sit spot.

Richard Louv’s latest book, Our Wild Calling, focuses on the meaningful interactions between humans and other species as a way of combatting “species loneliness”. (Photo: Courtesy of Richard Louv)

LOUV: Well, John Young is one of the world's preeminent nature educators, and he takes hundreds of people out into the woods to learn bird language. But one of the things he recommends in a book called Coyote's Guide, that I wrote the introduction to, he advises kids and adults to find a special place in nature, it could be in your backyard. Whether it's under a tree or the end of the yard, it can be next to a creek, and he recommends you sit there for a long time. You know, know it by day, know it by night. Know it when it rains and when it snows. And he says know the birds that live there. Know the trees that live in it. Get to know these things as if they were your relatives. It seems to me that doing this can reduce our sense of isolation right now in particular. Not only the isolation that we're feeling right now because of sequestering ourselves. But this deeper loneliness that I've written about in Our Wild Calling, which is species loneliness. Our deep, deep feeling that we're alone in the universe, and we can't be. And so by sitting at a sit spot in your backyard or wherever, pretty soon you notice you're not alone in the universe. There's a lot of life around us. One of my favorites, when I was a kid, I'd go down to the creek and I'd sit next to the creek. And as you approach, all the frogs jump into the water, but then if you sit there, you know, really quiet wait for a long time, and the frogs start popping up, one after another, and you just watch them. It's, it's a lot like meditation. But I think it's even deeper in some ways than some forms of meditation. And the primary thing I think we get from that, in some strange way is not feeling as alone.

CURWOOD: Now, you're in the city, sequestered. Maybe you have a sort of three-by-three patch of dirt next to the front walk to your apartment house, a porch maybe. How do you do that?

LOUV: You know, the piece you're referring to, I posted it earlier this week. And I went back through and realized that I was reflecting way too much my own experience. I grew up at the edge of the suburbs. There are a lot of people that don't live in the suburbs, who don't get to live in Julian, up in the mountains like I do. And we've talked about this a lot at Children and Nature Network, the whole issue of equity, about the distribution of parks. I mean, you can tell people go to the park, many neighborhoods, it's quite unlikely there's a park there and if it is, you're competing with other issues. So, the idea that this kind of thing is available to everybody is is not true, but nature is everywhere. So, I went through the piece and I added quite a bit of that. You know, if you can't go outside today, set up what I call a world watching window, bring the outside in. That's finding a window view or other view. It's designed to induce our feelings of deep relaxation and awe, and vitality. Watch the birds, watch the life outside that window. Even in the densest urban neighborhoods, there are birds. Also, you can do cloud watching, you can sit inside and look at the different kinds of clouds and watch the weather go by. A couple years ago, I was visiting a guy who's head of one of the major conservation organizations. And I met his son who literally had a condition, he could not go outside, period. But he loved nature. And he talked about it a lot. And this idea of being able to see beyond the walls of your building. You can still do that. And I know that most of us would rather not be inside now but I think that that's an extraordinary important thing we can do.

Richard Louv recommends bird- or cloud-watching for those living in dense city environments. (Photo: Kim Anh, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Among the suggestions you have about connecting with nature in this time of sequesteration is to get a big load of dirt and dump it in the backyard for the kids to play in. What are you talking about?

LOUV: Well, I think that's one of my favorite ideas because it's so simple. A guy named Norman McKee, several years ago wrote me an email and he said that his kids weren't getting out in nature, he couldn't hardly get them out the front door. And he drove and he bought a load of dirt that he put in the back of his pickup and he drove home. And he dumped it in the front yard for his kids to dig in. And immediately they were outside, they were digging in it, they were making things, they were making tunnels, and roads, and he sent me a picture. It's a great picture of his little girl, three and a half, four years old. She's sitting on top of this giant hill of dirt that he had just dumped in there. She's sitting there waving her plastic bucket and her plastic shovel around her and she looks so happy. You know, sometimes these really simple things are the best things to do.

CURWOOD: One of the suggestions that you have for people to do in this time of sequesteration is to tell nature stories. How does that work?

LOUV: Well, that's something we can do all the time. But maybe that's particularly true right now. Imagination is a wonderful thing. It gets us out of our shell, it gets us out of our current reality. And we don't tell nature stories enough. Now our ancestors did, they went outside, they went into the forest and they got to hunt to bring back food, whatever it was, then they came back and they would sit around the fire with the others in their clan and they would tell stories about what happened and sometimes they would act them out with their bodies. They would dance these stories, they would become the bear. I think that much of what we see on YouTube, all those YouTube videos of animals. I went to sleep the other night while watching cat videos, by the way. It's very soothing. But I think a lot of that reflects our desire as a species, again, not to feel alone. To, to get out of our species loneliness, I hope one of the things that happens is that they begin to tell stories, they sit around the kitchen table and tell their stories. Have parents tell their stories of animals they encountered when they were kids. The kids tell the stories of what happened just the other day in the backyard when they ran into this huge grasshopper. You know, people change when they're telling those stories, their affect changes. They become very excited about life. So, now that we're having to spend more time indoors, I think that's a good thing to do is to tell these stories, and also to tell the stories about what might happen next fall. Maybe we'll go outside more next fall, or whenever this lifts. You know, we'll not only value each other more, I hope. But maybe, we'll value our larger family, the animals and plants all around us more, I hope.

Author and advocate Richard Louv has written nearly a dozen books about connecting with nature. (Photo: Eric B. Dynowski)

CURWOOD: In times like this, I think we could all do with a little hope. What do you have to offer us in terms of hope?

LOUV: By missing nature, right now and each other, this may be a way to fall in love again, with nature and with each other. I'm thinking about imaginative hope. I'm not talking about blind hope. Imagine what would the world would be like a lot of things went right, if we acted on climate change, if in fact, we set aside big areas for biodiversity, imagining a different kind of city where it's filled with biodiversity. If we begin to imagine that now, and I hope that this occurs, particularly with young people, it's a lot more likely that we will get that world than we will get the post-apocalyptic world that we're to used to imagining.

CURWOOD: Richard Louv is an author and his latest book is Our Wild Calling. Richard, thanks so much for joining us today.

LOUV: Oh, thanks. I really appreciate it.

Related links:

- Children & Nature Network | “10 Nature Activities to Help Get Your Family Through the Coronavirus Pandemic”

- The Children & Nature Network

- Click here for more on Richard Louv and his books

[MUSIC: Liz Story, “17 Seconds To Anywhere” on 17 Seconds To Anywhere, by Liz Story Windham Hill Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Candice Siyun Ji, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth