50 Years of Environmental Law

Air Date: Week of April 24, 2020

The Bald Eagle, the national bird of the United States, was nearly extinct in the country in the late 20th century, but due to the Endangered Species Act, its wild populations have recovered and it is no longer considered a threatened species. (Photo: Jerry McFarland, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

1970 saw the birth of major environmental laws including the Clean Air Act and the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA. Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau and Host Steve Curwood reflect on the development of environmental law in the 50 years since: important successes like improved air and water quality throughout the nation, and major shortfalls like the lack of climate legislation. Finally, the pair look forward from today, considering the most prominent environmental challenges in the 21st century.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Since the 1970’s Pat Parenteau has been a leading environmental lawyer. He has counseled major conservation organizations, served as regional general counsel for the EPA, and t taught environmental law. These days he’s a professor at the Vermont Law School and joins us now and to offer his insights on the progress of environmental law since that first Earth Day and how the challenges have changed.

Welcome back to Living on Earth, Pat!

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Steve, always good to be with you.

CURWOOD: So, where were you on April 22, 1970?

PARENTEAU: I was in law school. In fact, I was probably getting ready for final exams in my first year of law school. So I do remember that day, and luckily I passed.

CURWOOD: So, what was your personal connection to Earth Day?

PARENTEAU: Well, you know, at the time, I was more focused on opposing the war in Vietnam, and trying to make sure that I didn't have to go, frankly. But I was aware of this burgeoning movement called the environmental movement. And my upbringing in Nebraska was very much oriented to the outdoors. My family was very active; camping, hunting, fishing, I did all that sort of thing. So, I was sort of imprinted at an early age with both the beauty of nature and to some extent, I guess, the threats that we were already beginning to see. So, there was a confluence of things happening in my life at that time.

CURWOOD: But you had no idea you'd become an environmental lawyer.

PARENTEAU: None. I started off in legal services representing the poor, representing indigent clients in the old Legal Services Corporation days. So, most of my early legal work was making sure people didn't get evicted, making sure that they were eligible for their welfare benefits, making sure they weren't being discriminated against in employment and in schools. So, I was quite a bit of a civil rights lawyer for the first couple of years of my career. But, I quickly pivoted and began looking at environmental law.

CURWOOD: Well, I'm not sure there's that much difference, right? I mean, all these animals are getting evicted from their habitats, and the right to clean air seems to be abrogated a lot.

PARENTEAU: Very true. Very true, and one of my first cases at Legal Services was representing a Black community in Council Bluffs, Iowa right across the river from Omaha where I was stationed. And they were going to put a great big interchange right in the middle of their community, separate the schools from their homes, impact a little park that they used. And so, I brought a lawsuit that actually prevented that interchange from being built.

CURWOOD: So, that mindless development piece kind of sounds like an environmental lawsuit to me.

PARENTEAU: Yeah, in fact, in those days, we called it NEPA. We call it NEPA now, but of course, it was a brand-new statute in 1970. And nobody knew much about it. But I went to a conference in St. Louis, where there were some lawyers, in those days the early advance guard of the environmental movement, we're talking about using this new law to stop bad federal projects. So that's where I got the idea, from a conference in St. Louis, went back to Omaha, brought the lawsuit and said, you know what, Department of Transportation? You haven't written an environmental impact statement for this interchange, and you can't build it. And lo and behold, the court agreed that they needed to comply with NEPA. And in the meantime, they decided to abandon the interchange, or at least move it. So, we never had to go to the final battle over that particular project.

CURWOOD: So, remind me what the acronym NEPA stands for.

PARENTEAU: Yes, it's the National Environmental Policy Act. NEPA.

CURWOOD: Isn't that the way often in the law, though, if you assert your rights, that people can and might just back down?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, in fact, that's particularly true of NEPA. And a lot of other procedural environmental laws. You're really buying time. You're trying to allow the political process or in some cases, the economy to bring about change. I mean, what we're seeing with the coal industry in decline, you know, that's market-driven. And the longer that you can delay projects that do damage to air and water and land and wildlife, the better chances you have of maybe coming up with an alternative. So, that's very much part and parcel of environmental law over the last 50 years.

CURWOOD: So, it's been some 50 years, what has environmental law accomplished, do you think?

PARENTEAU: It's really accomplished an amazing amount. When we started off in 1970, raw sewage was pouring into all the rivers and lakes of America. The Connecticut River, our beloved Connecticut River here in New England, it was called the best landscape sewer in America in 1970. Now it's clean, it's fishable, swimmable, I fish it, I swim it all the time. So that's one small example. But the water quality improvement, with a massive investment of federal funds, almost $10 billion to treat all the sewage. The air quality. You know, Los Angeles still has serious air quality problems, but you're no longer fainting in the streets and choking on the air and your eyes watering. You know, we've taken the lead out of the gas, we've reduced air pollutions across the board. We've saved hundreds of thousands of lives through improved air quality. We've tackled some of the biggest problems. Remember stratospheric ozone depletion? The hole in the ozone layer?

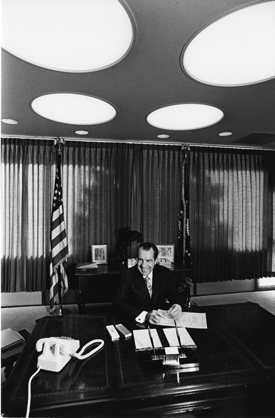

President Richard Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act, known as NEPA, into law on New Year’s Day, 1970. (Photo: Richard Nixon Presidential Library)

CURWOOD: Indeed.

PARENTEAU: We finally tackled that with the Montreal Protocol, which the United States was a very leading player on. And the ozone layer is still not fully healed and repaired, but it's on its way and we've made major progress in getting rid of those ozone depleters. We banned DDT. We banned PCBs. We banned asbestos. So we've taken out a lot of the major threats to public health. The Endangered Species Act, much criticized for not doing enough, has done an awful lot. The bald eagle has fully recovered, the peregrine falcon, the gray whale, the brown pelican. Even the controversial snail darter has fully recovered and is about to be delisted. The reintroduction of the gray wolf to the Yellowstone ecosystem, a major conservation achievement. So many, Steve, and I could go on all day probably but one other one that really sticks out is with the stroke of a pen, Jimmy Carter saved 100 million acres of wilderness in Alaska and I was in the Oval Office, lucky enough to be in the Oval Office when that deed was done. So we've created massive marine sanctuaries, wilderness areas, national monuments, protecting some of the grand vistas and natural heritage of America. All kinds of really terrific things have happened over those 50 years.

CURWOOD: So, we should be saying "Woohoo, Earth Day!" A lot to celebrate on this birthday, huh?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, we should be saying that. And then, of course, we face the reality of the moment, which is problems that we just did not foresee in 1970. The biggest one, of course, climate disruption, but so many more. All the plastics in the ocean, the forever chemicals. You know, we knew about things like mercury, we knew that was a big problem. We had to get it out of the air, had to get it out of the water, but now we're dealing with these things called PFAS and PFOA. These fluorinated compounds that are in everyday use in Teflon, in water-resistant clothing, in fire extinguishers and these are called the forever chemicals because they don't break down. And they're ubiquitous in our economy. There are 600 different compounds like this in commercial use in America. They're in the groundwater, they're in the surface water, they're in the sewage sludge. Same thing with pharmaceuticals. The United States Geological Survey has said, virtually everything that's in your medicine cabinet is probably in your water supply. And we're circulating this stuff over and over again. And of course, now we see this pandemic, with COVID going on, circulating throughout the world. So, the problems that we're facing today are even more comprehensive and more difficult, more global than anything we imagined in 1970.

CURWOOD: Pat, so, looking back, what would you consider to be some of the most prominent failures in this past half-century in terms of environmental law?

PARENTEAU: Well, several things. One, we treated the symptoms, not the causes. All of the environmental problems are rooted in our economic system. And nothing could make that case stronger than the problem with climate disruption and carbon, which is ubiquitous throughout all of our economies, right? And so, environmental law looked at treating the sources of pollution at the source, or end of the pipe, or in the top of the smokestack. And that seemed to be a reasonable strategy. At the time, it was very localized. We didn't understand how these pollutants circulate all through the globe, around the globe, and long-distance transport of acid rain, and ozone, and all of that. So, we were looking at pinpricks on the landscape, pinpoints where we could focus our regulation instead of asking the question, why are we producing the energy in this way? Why are we producing our crops in this way? And going really back to the core of the problem, which is the way we use the land, and the way we generate economic activity, profits, jobs, and all the rest. It took us many, many decades, I would say, to realize that it was a whack-a-mole problem. The minute you corrected one problem, it popped up in another place. We used to chase pollution around. Sewage sludge is a good example. What do you do with it? For a while, we thought the best thing to do with it, if you live near the ocean is dump it in the ocean. That's what we did on the east coast. If that didn't work, then you put it in a landfill. But if you put it in a landfill, it leaks into the groundwater. So if that didn't work, you burned it in an incinerator. But if you burned it in an incinerator, then you had air pollution, and a lot of those incinerators went into minority communities, low-income communities, created environmental justice problems that we're still living with. So, lots of mistakes about not focusing on the root causes of the problem. One other that I'll mention, we put too much faith in top-down regulation, federal regulation. Most of our environmental law in the country, of course, began in the 70s with the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, NEPA, the Endangered Species Act, many, many more. And so, the idea was, well, if we get national legislation, and we create an agency, the Environmental Protection Agency to implement these laws, and we get these other federal agencies in the Department of Interior and the Department of Agriculture, to obey these laws, then it'll all be good. Turns out, one of our understandings now is that most of what we need to do is at the local level, and instead of top-down, we're seeing more bottom-up. Most of the innovation we're seeing these days is coming from the cities. It's coming from county governments, and to some extent from state governments, obviously not coming from the federal government. That's been a huge change.

CURWOOD: Yeah, talk to me about some examples of what you see from the bottom-up in counties, and in towns, and cities, and states.

Green roofs are an example of bottom-up environmental advancements. (Photo: International Sustainable Solutions, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

PARENTEAU: Just today, with my class, I was going over low impact development guidelines. All the major cities, New York, Chicago, Seattle, many others are looking at their footprint of development and saying, we need to do a better job of building in concert with nature, taking advantage of natural systems, green space, open space, forested areas, park areas, places where you are reducing the amount of impervious surface so that you don't get this massive amount of runoff of pollution. And you get more penetration and infiltration into the soil and you get more take up of pollutants by vegetation, instead of going into receiving waters. And you get better treatment overall slowing down the rate of runoff. Low impact development is attacking the source of the problem. How do you build, can you build consistent with nature? There was a book by Ian McHarg, many, many years ago called Design with Nature. Some of those ideas are now being incorporated in local ordinances, and so forth. The same thing can be said with renewable energy and energy efficiency. It's the cities that are leading the charge on installing solar panels and buying clean energy from wind farms and thereby creating the financial capacity to expand those renewable energy sources. And you can talk about green roofs in very many cities where you're using the power of natural systems to collect water and treat it and cool the cities. I mean, the heat island effect is becoming a significant threat to people's security with rising temperatures and so forth. So, the cities, I would say are the frontline in many ways, but they're also the innovators right now with environmental and land use policy.

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Now, back to our conversation with Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau. I asked him how the politics of environmental law have changed since that first Earth Day back in 1970.

President Jimmy Carter signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act on December 2, 1980, an event that Vermont Law Professor Pat Parenteau was present for. It is the single largest expansion of protected lands in history. (Photo: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

PARENTEAU: One of the most dramatic things I've seen, when I was in Washington, DC in the early 70s, we were putting these laws together, and in some cases, amending them and defending them from attack. Everything that we did in those days was bipartisan, everything. I can't remember a single major piece of legislation that didn't have strong bipartisan support. I won't say it was 100%, even between Democrats and Republicans, but there was always very strong Republican leadership and participation. Many of those Republican leaders, of course, came from New England, and came from the northeast, but not strictly limited to the northeast. So, there were debates, there were arguments, there was pushback from the more conservative members of Congress. But we would say to ourselves, we're not leaving this room until we agree on something. And the idea of just walking away from problems just never occurred to us at that time. You can't say that about today. The politics, as everybody knows, are hopelessly divided and partisan and really toxic. And there was nothing approaching that level of hostility in the 70s and even into the 80s. It did begin to change in the 90s. Some things were going on where the bloom was off the rose, if you will, on environmental law. We haven't passed a really comprehensive environmental law since the 1990 amendments to the Clean Air Act that dealt with acid rain, that dealt with stratospheric ozone depletion, and many other things. So that's the biggest political change. We no longer have a partnership between the Republican Party and the Democratic Party in terms of attacking these monumental issues we face.

CURWOOD: What do you think that is, Pat? Some might say that around 1980, the major oil companies became aware of the threat of climate disruption and that ultimately, government regulation could put them out of business, so they needed to disrupt government regulation. What would you say to that argument?

PARENTEAU: Well, I have to agree with it. Because one thing we did not know, in the 80s was that some of the major corporations in the oil and gas industry, fossil fuel industry, were set about with a deliberate campaign to mislead about the effects of things like climate disruption, but other things too. And that has now all been documented and the proof and the evidence of what these companies knew, and how they were misleading people and saying the science was uncertain, and so forth. And they knew that the science was not uncertain. They knew that their products were causing damage and could cause even greater damage into the future. We didn't realize the lengths to which some of these industries would go to block successfully. I hate to say, efforts to address some of these problems early on, we knew that the automotive industry resisted a lot of the Clean Air Act initiatives. But that opposition was out in front in public. What we didn't know was what was going on behind the scenes from these industries. And of course, all through the 70s and 80s, into the 90s, we weren't dealing with these massive well-funded campaigns of deception, so well-documented in Merchants of Doubt, Naomi Oreskes' marvelous book. And we didn't have the Koch brothers. We didn't have the American Legislative Council. We didn't have this massive amount of money pouring not only into electoral politics but pouring into lobbying. And so our early efforts to get laws passed, looking back on it, were remarkably easy compared to where we are today with this entrenched, well-funded opposition to dealing with these problems.

Author Naomi Oreskes (left) and Editor Dennis Dimick (right) at a showing of the Merchants of Doubt movie at the World Economic Forum. Merchants of Doubt was written by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, and it shows parallels between misinformation campaigns on a variety of environmental issues. (Photo: World Economic Forum, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So now let's take a look forward from this point, Earth Day 2020. What are the major changes challenges facing environmental law now in the 21st century?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, they're all global. I mean, the overarching existential challenge is certainly climate disruption. And I hate to say that despite a lot of promising initiatives, you know, the growth of the solar and wind portion of our energy mix, the movement to electric vehicles, electrification of the transportation system, the improvement in efficiency in various places, it's not working nearly as well or as fast as it needs to. Of course, this current pandemic we're dealing with is knocking back some of this, but the data on what's happening as a result of climate change is truly scary. It does not look as if we are now in any position to hold these temperatures anywhere near the two degrees Celsius cap that the IPCC has said we need to. In fact, the course they say, we really should be holding it to 1.5 degrees Celsius increase from carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. We're on track to a four-degree Celsius world this century. And that simply means large areas of the globe will be uninhabitable. It might not mean the end, total end of civilization, but it's a world nobody would want to inhabit.

Former EPA Regional Counsel Pat Parenteau teaches environmental law at Vermont Law School (Photo: Courtesy of Vermont Law School)

And yet when you try to think about where are we seeing the real movement to accomplish these reductions, this idea of peaking emissions by 2030 and achieving net-zero carbon by 2050. You know, the amount of effort that would have to be expended to do that is mind-blowing. But here's the thing, we do have probably a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity right now to make that leap forward that the science says we need. The fossil fuel industry is on its back right now, the oil industry is down, the coal industry is dying, the gas and fracking are down. The government could right now buy up most of the fossil fuel reserves that are on the books at basically bargain basement prices, you know because the economy is down so much. Buy them up, and then with a massive infusion of federal stimulus aimed at fast-tracking and deploying renewables on the scale needed. There is, frankly, an opportunity right now to catch up on our failure to address carbon pollution for so many decades. That's a one-time opportunity and at the same time, with the need of Congress to infuse the economy, to rebuild the economy, to put people back to work. What's the fastest-growing job sector in the American economy? Solar. Installation of solar panels, right now solar is flat on its back because people can't get out and do this. But it could come roaring back, as our president sometimes likes to say. It could roar back in the right way. And it could stand up some of these renewable energy sources in a way that would truly make a dent in this carbon pollution.

CURWOOD: But there's no time to waste, it's the last call, you say.

PARENTEAU: Last call. God's last offer.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau is a professor at Vermont Law School. Thanks so much for taking this time with us today, Pat, and happy Earth Day.

PARENTEAU: Happy Earth Day, Steve, to all of us. Thank you.

Links

EPA’s Environmental Protection Timeline

Click here to listen to our most recent segment with Pat Parenteau

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth