April 24, 2020

Air Date: April 24, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Reflecting on 50 Years of Earth Day

View the page for this story

This year, Earth Day turns 50. And from humble beginnings Earth Day has grown into the world’s largest secular holiday, celebrated around the world each year by more than a billion people. Activists, scientists, and pastors alike share their reflections for this special Earth Day. (07:51)

Celebrating 30 Years of ‘Living on Earth’

View the page for this story

In April 1990, with a growing awareness of the potentially catastrophic impacts of global warming, Steve Curwood launched four pilot shows of “Living on Earth”. The weekly radio program has run continuously for nearly 30 years, and Host and Executive Producer Steve Curwood reflects on the challenges and rewards of carrying on the unceasing work of covering environmental news. (03:55)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In Beyond the Headlines this week, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood look at the negative price of oil and the drop in greenhouse gas emissions related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Next, they discuss an innovative use of fungus: to grow a watertight, seaworthy, sustainable boat. Finally, the duo looks way back in the history calendar to the founding of the Hudson’s Bay Company and its longtime fur business. (04:08)

50 Years of Environmental Law

View the page for this story

1970 saw the birth of major environmental laws including the Clean Air Act and the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA. Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau and Host Steve Curwood reflect on the development of environmental law in the 50 years since: important successes like improved air and water quality throughout the nation, and major shortfalls like the lack of climate legislation. Finally, the pair look forward from today, considering the most prominent environmental challenges in the 21st century. (21:08)

Stories and Poetry for Earth Day

View the page for this story

Each person has a unique story to tell about what Earth Day and environmental protection means to them. Writers and activists share their poems and stories in this 50th anniversary celebration of our connection to the Earth. (09:31)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUEST: Pat Parenteau

REPORTER: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

A civil rights leader compares the activism of the '60s to the environmental movement of today.

DURLEY: In those days, we had a constitutional right to be able to ride in the front of the bus, or eat at a certain place. But we were being denied those rights, so we had to protest, and we had to march. In the climate environmental movement, everyone has a constitutional right to clean water and toxic-free air.

CURWOOD: Also, a look back at how environmental law has evolved since the first earth day.

PARENTEAU: When I was in Washington, DC in the early 70s. We were putting these laws together, amending them, and defending them from attack, everything that we did in those days was bipartisan. Everything. I can’t remember a single piece of environmental legislation that didn’t have strong bipartisan support.

CURWOOD: Earth Day turns 50, this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Reflecting on 50 Years of Earth Day

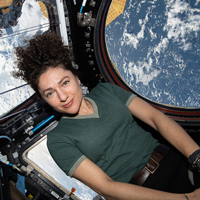

NASA astronaut and Expedition 62 Flight Engineer Jessica Meir poses for a portrait inside the International Space Station's "window to the world," the cupola, on April 12, 2020. The orbiting lab was flying above the middle of the Pacific Ocean at the time this photograph was taken. (Photo: NASA Johnson, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

To honor the 50th Earth Day organizers originally planned massive rallies around the United States and the world. But the Coronavirus pandemic made that impossible. So, instead, the Earth Day celebration went online with virtual teach-ins, musical performances, lectures, and speeches, near and far.

MEIR: From the International Space Station I am NASA astronaut Jessica Meir, observing with all of you the 50th anniversary of Earth Day. During my stay here on the ISS, one of my favorite activities was to look out of the window and admire our beautiful home planet, taking a moment to appreciate the extraordinary diversity of ecosystems and life in Earth's cradle. This year marks 50 years of a concerted effort to protect our fragile environment and conserve the natural balance of Earth's interconnected systems. Using that knowledge to live sustainably on our home planet, protect lives around the world, and adapt to natural and human-caused changes. Congratulations and thank you, to all those supporting and protecting our earth on this 50th anniversary of Earth Day.

IMO: Hi, my name is Gerald Imo, I coordinate a team of volunteers and organizations towards achieving groundbreaking Earth day events in Nigeria. Earth day to me is an opportunity for everyday Nigerians to speak out about environmental and climatic issues that are making the earth less habitable for us, and all forms of life that exist within Nigeria. It’s also an opportunity to shake up our government and companies, both national and international, and awaken them to take responsibility for the environment.

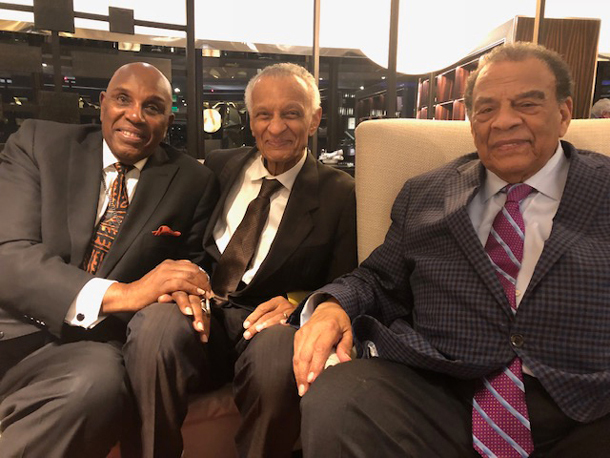

REV. DURLEY: This is the Reverend Dr. Gerald L. Durley, I live in Atlanta, Georgia. I’m Chair of the Board of Interfaith Power & Light, and for years and years, I was a civil rights leader and marcher with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. I feel that the environmental movement is almost the same as what we went through in the 60s – 61, 62 – with the civil rights movement, because in those days, we had a constitutional right to be able to ride in the front of the bus, or buy houses where we could, or eat in a certain place. But we were being denied those rights, so we had to protest, and we had to march. But constitutionally we were given those rights. In the climate environmental movement, everyone has a constitutional right to clean water and toxic-free air. But we are being denied that because of the fossil fuel industry and many of the energy companies, so we’ve got to use some of the same tactics by getting out there and coming together across racial lines and across faith lines to stand up for our constitutional rights so that we can sustain the planet.

Rev. Gerald Durley (left) with fellow civil rights advocates C.T. Vivian (middle) and Andrew Young (right). (Photo: Courtesy of Rev. Durley)

We never left a movement or a meeting in Selma, in Birmingham, and Mississippi, unless we came together, and sometimes Martin would be in the middle of it, or Andrew Young, and we'd pray for the insights, we'd pray for the wisdom, we'd pray that we would say the right thing at the right time for the right person. And that's what we've got to do right now. We've got to speak truth to power to understand that it's only when we come together, as a human body together, that we can begin to appreciate the animals and the insects and the birds and the bees and the trees because we were all initially created by a divine deity that said, I created all of you in my own image. Let us take care of the beautiful Earth that God has created for us. And that's in every single religion and every single faith.

SANTER: My name is Ben Santer, and I'm a climate scientist at Lawrence Livermore National Lab in Livermore, California.

Nearly 25 years ago, my life changed. 25 years ago, I was in Madrid, in the beautiful Palacio de Congresos. And I was part of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change or IPCC. The role of the IPCC is to advise the governments of the world about the physical climate system, the causes of climate change, the likely impacts of climate change on stuff we care about: human health, agriculture, water, resources, energy.

And after two years of work, there we were in Madrid, roughly 100 governments from all over the world and several hundred scientists trying to finalize the language and at the end of those three days in Madrid, we finalized this summary for policymakers. And the bottom-line finding was 12 words. “The balance of evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate.” Those 12 words changed the world. It was the first time that the international scientific community spoke with one voice and said, we see the scientific equivalent of the handwriting on the wall. Humans are no longer innocent bystanders in the climate system. Humans are actively changing the climate by burning fossil fuels and increasing levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Ben Santer is a Climate Researcher at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. (Photo: Courtesy of Ben Santer)

A lot of powerful people and a lot of powerful countries and corporations did not like that balance of evidence finding. I found myself under attack. There were investigations in Congress, there were calls for my dismissal with dishonor from my position at Lawrence Livermore National Lab, and I found myself in the position of defending the balance of evidence finding and the scientific process by which it had been reached.

So 25 years ago, I learned an extremely important personal lesson. Science matters. Words can change the world. The work of scientists, in trying to understand human effects on climate is critically important. We ignore science at our peril. How important those lessons seem today in the world of COVID-19 when we have to pay attention to science, in order to make wise decisions on how to diminish risk, reduce risk to millions of individuals, billions of individuals all over the world.

So, on Earth Day, I've had an opportunity to reflect on that lesson learned 25 years ago, and the importance of science and the importance of standing up for science. There is no point in being a climate scientist or an epidemiologist if you're unwilling to defend that hard-won scientific understanding. So it seems wise to reflect on these things on Earth Day. And also to recognize that the shape of our climatic future is something that concerns all of us. And something that all of us has some say in determining the kind of world that our kids and grandkids grew up in. That's not just a decision for the rich and powerful for a few politicians. That decision is for all of us. We all have some say in the shape of the world that we live in and our kids and grandkids will live in.

CURWOOD: That was climate scientist Ben Santer. We also heard from Reverend Gerald Durley, activist Gerald Imo, and astronaut Jessica Meir. We’ll have more from the virtual Earth Day celebrations later in the Broadcast.

Related links:

- Earth Day | “Earth Day at Home”

- #EarthDayatHome with Jessica Meir on the Space Station

- About Interfaith Power and Light

- About Faith Climate Action Week

- Climate One | “What it’s like to be a Climate Scientist”

- Click here to read stories by Ben Santer published in Scientific American Magazine

[MUSIC: Joseph Fire Crow, “Horse Stealing Song” on The National Parks – America’s Best Idea (soundtrack), by Joseph Fire Crow, The National Parks Film Project]

Celebrating 30 Years of ‘Living on Earth’

Living on Earth Host and Executive Producer Steve Curwood in the recording studio. (Photo: Courtesy of Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: This Fiftieth anniversary of Earth Day marks a wonderful and humbling milestone for this radio program, because thirty years ago with help from friends, especially Deborah Stavro Lapides and George Homsy, I created and broadcast the first 4 pilots.

As a journalist, I had come to believe that environmental change was the greatest story largely ignored by the media and it was my duty to try to make a difference.

I was taught that the freedom of the press is embedded in the US constitution because part of the power of the people in a free society is the power of the press.

Steve Curwood and public radio legend Bill Siemering, the author of NPR’s original mission statement. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

Free citizens in a democracy need to be well-informed by the truth, and it’s the duty of the press to tell that truth with the best stories.

It can be risky, to put it mildly.

I worked at the Boston Globe just after college under the leadership of editor Tom Winship when the paper defied President Nixon and the federal government and published leaked Pentagon Papers after the courts had muzzled the Washington Post and the New York Times.

Living on Earth Host and Executive Producer Steve Curwood. (Photo: Living on Earth)

Tom also refused to back down during coverage of school desegregation in Boston even after somebody fired a barrage of bullets into the newsroom building.

So, with those examples and others in mind, when I first became aware of global warming in 1989, I knew I had to act.

And my key source was Scientist George Woodwell, who made a simple and compelling case.

If humanity kept burning fossil fuels and cutting down trees, he said, eventually global warming would start melting arctic permafrost and start releasing the gigatons of carbon stored there.

So, with more and more carbon coming out of the permafrost there would be even more and more warming and at some point, this feedback loop would become a runaway reaction beyond human control and civilization would end.

Wow, talk about a story!

Bigger than the economy, bigger than war and peace, and something people needed to know.

And, by the way, as I did my research, I also saw the natural and built environments were headed for trouble beyond climate concerns, with pollution compounding the loss of habitat and species.

Host and Executive Producer Steve Curwood piloted the Living on Earth program in April 1990. (Photo: Living on Earth)

So, with an eye on informing the public my response as a journalist was to tap my experience as a radio producer and presenter and start this program.

The first four shows considered nuclear power to address climate risk, the burdens of environmental injustice, overfishing the oceans, and the intelligence of animals and those themes remain today.

Our team has won many awards and accolades, but we have also drawn plenty of fire from those who feel their profits might be threatened by our truth-telling, especially those who have told the lies of climate denial.

Fossil fuel and chemical industry interests have led the attempts to bully and intimidate us with verbal and written threats, lobbied to cut our federal funding, and put pressure on stations that carry us.

But Living on Earth is still here, bringing you the stories many in the industry would rather never see the light of day.

And along with bad news, we have been able to cover some truly bright spots.

As far as the climate story now goes, the good news is that society does have all the technology it needs to stop burning fossil fuels and cutting trees and instead pivot to a sustainable energy future.

But as humanity seizes the possibilities and taps free and limitless sunlight and wind, we don’t forget the stories of the coal miners and others who gave their health and lives to modernize the world.

And we keep advancing the many stories of environmental justice.

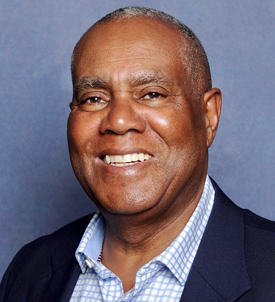

Steve enjoys recharging in the great outdoors. (Photo: Courtesy of Steve Curwood)

Somebody once asked how I can keep reporting on environmental change when it can be so depressing and frankly scary at times.

My answers are simple.

I get to work with great crews, with some of the smartest, most creative, and hard-working folks I know.

I also get outside a lot to better appreciate this great gift called Earth, as nature has an amazing ability to heal.

And I find the abundance of life is truly the best story there is.

Related links:

- Explore Living on Earth’s extensive archives!

- Connect with Steve Curwood via Twitter

- About ecologist George Woodwell

- “A World to Live In” by George Woodwell

- Woods Hole Research Center: About Steve Curwood

- Published in 1989, Bill McKibben’s “The End of Nature” helped bring global warming to the public’s attention

[MUSIC: Yungchen Lhamo, “Happiness Is…” on Gardens of Eden, by Yungchen Lhamo, Putumayo World Music]

BASCOMB: Coming up – A look back at some of the successes in environmental law over the last 50 years and challenges that lie ahead. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green, and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Expansions: The Dave Liebman Group, “Endive” on Samsara, by Dave Liebman, Whaling City Sound]

Beyond the Headlines

The dramatic drop in demand for oil, due to the shutdown of world economies by coronavirus, has profound environmental implications. (Photo: Aaron Goodwin, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Let's take a look now Beyond the Headlines with Peter Dykstra Peters, an editor with environmental health news as ehn.org and daily climate.org. He's on the line from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter. Happy Earth Day.

DYKSTRA: Happy Earth Day, Steve. And you know, while we're all obsessed with COVID, with very good reason, there are a whole lot of things happening related to COVID-19 that are happening to fossil fuels. The oil industry was in the news because the bottom fell out of the oil market to the point where oil futures were a negative number, meaning that an empty barrel of oil had a higher price than a full barrel of oil.

CURWOOD: Yeah, that low price though, Peter, I don't think I'm gonna see folks at the gas station telling me that they'll pay me to take the gasoline away somehow. I don't think that's gonna happen.

DYKSTRA: No, it's not gonna work that way. Even though gasoline prices are way down. That usually has the negative impact of seeing more SUV sells seeing people driving more and more, but with literally billions of people, and some degree of confinement and shutdown around the world, the error is correspondingly cleaner or driving a lot fewer greenhouse emissions have taken an unexpected drop. All of this of course, for the wrong reasons, and it doesn't make up for this immense tragedy, multifaceted tragedy of the coronavirus.

CURWOOD: What else do you have for us today, Peter?

DYKSTRA: I have fungus Steve.

CURWOOD: Oh, wait for a second, Peter, are you okay?

Mycelium is the vegetative part of a fungus, consisting of a mass of branching, thread-like hyphae. (Photo: Brenda Dobbs, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DYKSTRA: No, I don't personally have fungus. I'm going to talk about fungus. And a small answer to climate change was found by a Nebraska college student named Katie Ayres. She got fascinated with mushrooms as part of a classroom assignment to find something that would address climate change. She ended up building a canoe out of mushrooms.

CURWOOD: Haha, well, how exactly did she do that though?

DYKSTRA: This is an eight-foot boat and it's actually made mostly from mycelium, which is very dense, fibrous roots that grow beneath mushrooms. They're tough. They're waterproof. What Katie did is build a wooden frame of a canoe and then just let nature take its course she let mushrooms and then mycelium fibers grow over the frame. And lo and behold, what came out of it is a waterproof, see where the eight-foot boat with a couple of paddles and paddles are made of wood, but the boat is made of mushrooms and fungus. She spent about 500 bucks on the whole project. It's not gonna solve climate change, but its little innovations like that'll help at least a little bit.

CURWOOD: That's amazing. All right, Peter. Well, let's take a look back in history now. You'll always have a good item for us. What do you have today?

DYKSTRA: We're gonna go way back in history this time, may 2 1670, England England's King Charles otherwise known as the Merrie Monarch chart, The Hudson's Bay Company in Canada. The Kingdom granted Hudson's Bay, a virtual monopoly over much of the business, and actually the politics in central Canada, making Hudson's Bay a de facto government for a huge part of North America. It's now the oldest Corporation in America, having grown from its fur trading and trapping roots.

Fur farming and the manufacture of furs both stress the environment. (Photo: Charisse Kenion on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: And what are they called now?

DYKSTRA: They're colloquially known as the Bay. The Bay is the largest chain of department stores in Canada. They also own Saks Fifth Avenue. And until recently, they own the Lord and Taylor stores.

CURWOOD: Well, I guess they're still in the fashion business, Peter.

DYKSTRA: They are actually they got out of selling furniture in the department stores entirely in the 1990s due to pressure from animal rights groups, but pressure from the marketplace, and several years later, they went right back into selling furs.

CURWOOD: I guess that's part of their DNA. Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is the editor of environmental health news. That's ehn.org and daily climate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more of these stories at the living on earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- TIME | “Will Low Oil Prices Help or Hurt the Fight Against Climate Change? That Depends on Us”

- Kearney Hub | “A Boat Made of Mushrooms: CCC Student to Present Her Fungal Creation at State Fair, Test the Waters on the Platte River”

- History on This Day | “Charles II Grants a Royal Charter to the Hudson’s Bay Company”

[MUSIC: Dave Bourne, “The Little Old Sod Shanty” on Saloon Piano Vol. III, author unknown, Old Coot Music]

50 Years of Environmental Law

The Bald Eagle, the national bird of the United States, was nearly extinct in the country in the late 20th century, but due to the Endangered Species Act, its wild populations have recovered and it is no longer considered a threatened species. (Photo: Jerry McFarland, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Since the 1970’s Pat Parenteau has been a leading environmental lawyer. He has counseled major conservation organizations, served as regional general counsel for the EPA, and t taught environmental law. These days he’s a professor at the Vermont Law School and joins us now and to offer his insights on the progress of environmental law since that first Earth Day and how the challenges have changed.

Welcome back to Living on Earth, Pat!

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Steve, always good to be with you.

CURWOOD: So, where were you on April 22, 1970?

PARENTEAU: I was in law school. In fact, I was probably getting ready for final exams in my first year of law school. So I do remember that day, and luckily I passed.

CURWOOD: So, what was your personal connection to Earth Day?

PARENTEAU: Well, you know, at the time, I was more focused on opposing the war in Vietnam, and trying to make sure that I didn't have to go, frankly. But I was aware of this burgeoning movement called the environmental movement. And my upbringing in Nebraska was very much oriented to the outdoors. My family was very active; camping, hunting, fishing, I did all that sort of thing. So, I was sort of imprinted at an early age with both the beauty of nature and to some extent, I guess, the threats that we were already beginning to see. So, there was a confluence of things happening in my life at that time.

CURWOOD: But you had no idea you'd become an environmental lawyer.

PARENTEAU: None. I started off in legal services representing the poor, representing indigent clients in the old Legal Services Corporation days. So, most of my early legal work was making sure people didn't get evicted, making sure that they were eligible for their welfare benefits, making sure they weren't being discriminated against in employment and in schools. So, I was quite a bit of a civil rights lawyer for the first couple of years of my career. But, I quickly pivoted and began looking at environmental law.

CURWOOD: Well, I'm not sure there's that much difference, right? I mean, all these animals are getting evicted from their habitats, and the right to clean air seems to be abrogated a lot.

PARENTEAU: Very true. Very true, and one of my first cases at Legal Services was representing a Black community in Council Bluffs, Iowa right across the river from Omaha where I was stationed. And they were going to put a great big interchange right in the middle of their community, separate the schools from their homes, impact a little park that they used. And so, I brought a lawsuit that actually prevented that interchange from being built.

CURWOOD: So, that mindless development piece kind of sounds like an environmental lawsuit to me.

PARENTEAU: Yeah, in fact, in those days, we called it NEPA. We call it NEPA now, but of course, it was a brand-new statute in 1970. And nobody knew much about it. But I went to a conference in St. Louis, where there were some lawyers, in those days the early advance guard of the environmental movement, we're talking about using this new law to stop bad federal projects. So that's where I got the idea, from a conference in St. Louis, went back to Omaha, brought the lawsuit and said, you know what, Department of Transportation? You haven't written an environmental impact statement for this interchange, and you can't build it. And lo and behold, the court agreed that they needed to comply with NEPA. And in the meantime, they decided to abandon the interchange, or at least move it. So, we never had to go to the final battle over that particular project.

CURWOOD: So, remind me what the acronym NEPA stands for.

PARENTEAU: Yes, it's the National Environmental Policy Act. NEPA.

CURWOOD: Isn't that the way often in the law, though, if you assert your rights, that people can and might just back down?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, in fact, that's particularly true of NEPA. And a lot of other procedural environmental laws. You're really buying time. You're trying to allow the political process or in some cases, the economy to bring about change. I mean, what we're seeing with the coal industry in decline, you know, that's market-driven. And the longer that you can delay projects that do damage to air and water and land and wildlife, the better chances you have of maybe coming up with an alternative. So, that's very much part and parcel of environmental law over the last 50 years.

CURWOOD: So, it's been some 50 years, what has environmental law accomplished, do you think?

PARENTEAU: It's really accomplished an amazing amount. When we started off in 1970, raw sewage was pouring into all the rivers and lakes of America. The Connecticut River, our beloved Connecticut River here in New England, it was called the best landscape sewer in America in 1970. Now it's clean, it's fishable, swimmable, I fish it, I swim it all the time. So that's one small example. But the water quality improvement, with a massive investment of federal funds, almost $10 billion to treat all the sewage. The air quality. You know, Los Angeles still has serious air quality problems, but you're no longer fainting in the streets and choking on the air and your eyes watering. You know, we've taken the lead out of the gas, we've reduced air pollutions across the board. We've saved hundreds of thousands of lives through improved air quality. We've tackled some of the biggest problems. Remember stratospheric ozone depletion? The hole in the ozone layer?

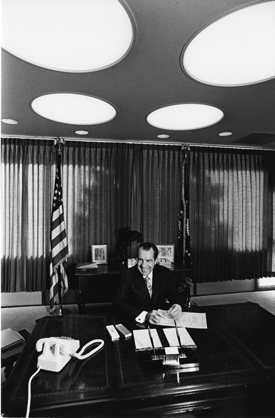

President Richard Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act, known as NEPA, into law on New Year’s Day, 1970. (Photo: Richard Nixon Presidential Library)

CURWOOD: Indeed.

PARENTEAU: We finally tackled that with the Montreal Protocol, which the United States was a very leading player on. And the ozone layer is still not fully healed and repaired, but it's on its way and we've made major progress in getting rid of those ozone depleters. We banned DDT. We banned PCBs. We banned asbestos. So we've taken out a lot of the major threats to public health. The Endangered Species Act, much criticized for not doing enough, has done an awful lot. The bald eagle has fully recovered, the peregrine falcon, the gray whale, the brown pelican. Even the controversial snail darter has fully recovered and is about to be delisted. The reintroduction of the gray wolf to the Yellowstone ecosystem, a major conservation achievement. So many, Steve, and I could go on all day probably but one other one that really sticks out is with the stroke of a pen, Jimmy Carter saved 100 million acres of wilderness in Alaska and I was in the Oval Office, lucky enough to be in the Oval Office when that deed was done. So we've created massive marine sanctuaries, wilderness areas, national monuments, protecting some of the grand vistas and natural heritage of America. All kinds of really terrific things have happened over those 50 years.

CURWOOD: So, we should be saying "Woohoo, Earth Day!" A lot to celebrate on this birthday, huh?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, we should be saying that. And then, of course, we face the reality of the moment, which is problems that we just did not foresee in 1970. The biggest one, of course, climate disruption, but so many more. All the plastics in the ocean, the forever chemicals. You know, we knew about things like mercury, we knew that was a big problem. We had to get it out of the air, had to get it out of the water, but now we're dealing with these things called PFAS and PFOA. These fluorinated compounds that are in everyday use in Teflon, in water-resistant clothing, in fire extinguishers and these are called the forever chemicals because they don't break down. And they're ubiquitous in our economy. There are 600 different compounds like this in commercial use in America. They're in the groundwater, they're in the surface water, they're in the sewage sludge. Same thing with pharmaceuticals. The United States Geological Survey has said, virtually everything that's in your medicine cabinet is probably in your water supply. And we're circulating this stuff over and over again. And of course, now we see this pandemic, with COVID going on, circulating throughout the world. So, the problems that we're facing today are even more comprehensive and more difficult, more global than anything we imagined in 1970.

CURWOOD: Pat, so, looking back, what would you consider to be some of the most prominent failures in this past half-century in terms of environmental law?

PARENTEAU: Well, several things. One, we treated the symptoms, not the causes. All of the environmental problems are rooted in our economic system. And nothing could make that case stronger than the problem with climate disruption and carbon, which is ubiquitous throughout all of our economies, right? And so, environmental law looked at treating the sources of pollution at the source, or end of the pipe, or in the top of the smokestack. And that seemed to be a reasonable strategy. At the time, it was very localized. We didn't understand how these pollutants circulate all through the globe, around the globe, and long-distance transport of acid rain, and ozone, and all of that. So, we were looking at pinpricks on the landscape, pinpoints where we could focus our regulation instead of asking the question, why are we producing the energy in this way? Why are we producing our crops in this way? And going really back to the core of the problem, which is the way we use the land, and the way we generate economic activity, profits, jobs, and all the rest. It took us many, many decades, I would say, to realize that it was a whack-a-mole problem. The minute you corrected one problem, it popped up in another place. We used to chase pollution around. Sewage sludge is a good example. What do you do with it? For a while, we thought the best thing to do with it, if you live near the ocean is dump it in the ocean. That's what we did on the east coast. If that didn't work, then you put it in a landfill. But if you put it in a landfill, it leaks into the groundwater. So if that didn't work, you burned it in an incinerator. But if you burned it in an incinerator, then you had air pollution, and a lot of those incinerators went into minority communities, low-income communities, created environmental justice problems that we're still living with. So, lots of mistakes about not focusing on the root causes of the problem. One other that I'll mention, we put too much faith in top-down regulation, federal regulation. Most of our environmental law in the country, of course, began in the 70s with the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, NEPA, the Endangered Species Act, many, many more. And so, the idea was, well, if we get national legislation, and we create an agency, the Environmental Protection Agency to implement these laws, and we get these other federal agencies in the Department of Interior and the Department of Agriculture, to obey these laws, then it'll all be good. Turns out, one of our understandings now is that most of what we need to do is at the local level, and instead of top-down, we're seeing more bottom-up. Most of the innovation we're seeing these days is coming from the cities. It's coming from county governments, and to some extent from state governments, obviously not coming from the federal government. That's been a huge change.

CURWOOD: Yeah, talk to me about some examples of what you see from the bottom-up in counties, and in towns, and cities, and states.

Green roofs are an example of bottom-up environmental advancements. (Photo: International Sustainable Solutions, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

PARENTEAU: Just today, with my class, I was going over low impact development guidelines. All the major cities, New York, Chicago, Seattle, many others are looking at their footprint of development and saying, we need to do a better job of building in concert with nature, taking advantage of natural systems, green space, open space, forested areas, park areas, places where you are reducing the amount of impervious surface so that you don't get this massive amount of runoff of pollution. And you get more penetration and infiltration into the soil and you get more take up of pollutants by vegetation, instead of going into receiving waters. And you get better treatment overall slowing down the rate of runoff. Low impact development is attacking the source of the problem. How do you build, can you build consistent with nature? There was a book by Ian McHarg, many, many years ago called Design with Nature. Some of those ideas are now being incorporated in local ordinances, and so forth. The same thing can be said with renewable energy and energy efficiency. It's the cities that are leading the charge on installing solar panels and buying clean energy from wind farms and thereby creating the financial capacity to expand those renewable energy sources. And you can talk about green roofs in very many cities where you're using the power of natural systems to collect water and treat it and cool the cities. I mean, the heat island effect is becoming a significant threat to people's security with rising temperatures and so forth. So, the cities, I would say are the frontline in many ways, but they're also the innovators right now with environmental and land use policy.

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Now, back to our conversation with Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau. I asked him how the politics of environmental law have changed since that first Earth Day back in 1970.

President Jimmy Carter signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act on December 2, 1980, an event that Vermont Law Professor Pat Parenteau was present for. It is the single largest expansion of protected lands in history. (Photo: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

PARENTEAU: One of the most dramatic things I've seen, when I was in Washington, DC in the early 70s, we were putting these laws together, and in some cases, amending them and defending them from attack. Everything that we did in those days was bipartisan, everything. I can't remember a single major piece of legislation that didn't have strong bipartisan support. I won't say it was 100%, even between Democrats and Republicans, but there was always very strong Republican leadership and participation. Many of those Republican leaders, of course, came from New England, and came from the northeast, but not strictly limited to the northeast. So, there were debates, there were arguments, there was pushback from the more conservative members of Congress. But we would say to ourselves, we're not leaving this room until we agree on something. And the idea of just walking away from problems just never occurred to us at that time. You can't say that about today. The politics, as everybody knows, are hopelessly divided and partisan and really toxic. And there was nothing approaching that level of hostility in the 70s and even into the 80s. It did begin to change in the 90s. Some things were going on where the bloom was off the rose, if you will, on environmental law. We haven't passed a really comprehensive environmental law since the 1990 amendments to the Clean Air Act that dealt with acid rain, that dealt with stratospheric ozone depletion, and many other things. So that's the biggest political change. We no longer have a partnership between the Republican Party and the Democratic Party in terms of attacking these monumental issues we face.

CURWOOD: What do you think that is, Pat? Some might say that around 1980, the major oil companies became aware of the threat of climate disruption and that ultimately, government regulation could put them out of business, so they needed to disrupt government regulation. What would you say to that argument?

PARENTEAU: Well, I have to agree with it. Because one thing we did not know, in the 80s was that some of the major corporations in the oil and gas industry, fossil fuel industry, were set about with a deliberate campaign to mislead about the effects of things like climate disruption, but other things too. And that has now all been documented and the proof and the evidence of what these companies knew, and how they were misleading people and saying the science was uncertain, and so forth. And they knew that the science was not uncertain. They knew that their products were causing damage and could cause even greater damage into the future. We didn't realize the lengths to which some of these industries would go to block successfully. I hate to say, efforts to address some of these problems early on, we knew that the automotive industry resisted a lot of the Clean Air Act initiatives. But that opposition was out in front in public. What we didn't know was what was going on behind the scenes from these industries. And of course, all through the 70s and 80s, into the 90s, we weren't dealing with these massive well-funded campaigns of deception, so well-documented in Merchants of Doubt, Naomi Oreskes' marvelous book. And we didn't have the Koch brothers. We didn't have the American Legislative Council. We didn't have this massive amount of money pouring not only into electoral politics but pouring into lobbying. And so our early efforts to get laws passed, looking back on it, were remarkably easy compared to where we are today with this entrenched, well-funded opposition to dealing with these problems.

Author Naomi Oreskes (left) and Editor Dennis Dimick (right) at a showing of the Merchants of Doubt movie at the World Economic Forum. Merchants of Doubt was written by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, and it shows parallels between misinformation campaigns on a variety of environmental issues. (Photo: World Economic Forum, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So now let's take a look forward from this point, Earth Day 2020. What are the major changes challenges facing environmental law now in the 21st century?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, they're all global. I mean, the overarching existential challenge is certainly climate disruption. And I hate to say that despite a lot of promising initiatives, you know, the growth of the solar and wind portion of our energy mix, the movement to electric vehicles, electrification of the transportation system, the improvement in efficiency in various places, it's not working nearly as well or as fast as it needs to. Of course, this current pandemic we're dealing with is knocking back some of this, but the data on what's happening as a result of climate change is truly scary. It does not look as if we are now in any position to hold these temperatures anywhere near the two degrees Celsius cap that the IPCC has said we need to. In fact, the course they say, we really should be holding it to 1.5 degrees Celsius increase from carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. We're on track to a four-degree Celsius world this century. And that simply means large areas of the globe will be uninhabitable. It might not mean the end, total end of civilization, but it's a world nobody would want to inhabit.

Former EPA Regional Counsel Pat Parenteau teaches environmental law at Vermont Law School (Photo: Courtesy of Vermont Law School)

And yet when you try to think about where are we seeing the real movement to accomplish these reductions, this idea of peaking emissions by 2030 and achieving net-zero carbon by 2050. You know, the amount of effort that would have to be expended to do that is mind-blowing. But here's the thing, we do have probably a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity right now to make that leap forward that the science says we need. The fossil fuel industry is on its back right now, the oil industry is down, the coal industry is dying, the gas and fracking are down. The government could right now buy up most of the fossil fuel reserves that are on the books at basically bargain basement prices, you know because the economy is down so much. Buy them up, and then with a massive infusion of federal stimulus aimed at fast-tracking and deploying renewables on the scale needed. There is, frankly, an opportunity right now to catch up on our failure to address carbon pollution for so many decades. That's a one-time opportunity and at the same time, with the need of Congress to infuse the economy, to rebuild the economy, to put people back to work. What's the fastest-growing job sector in the American economy? Solar. Installation of solar panels, right now solar is flat on its back because people can't get out and do this. But it could come roaring back, as our president sometimes likes to say. It could roar back in the right way. And it could stand up some of these renewable energy sources in a way that would truly make a dent in this carbon pollution.

CURWOOD: But there's no time to waste, it's the last call, you say.

PARENTEAU: Last call. God's last offer.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau is a professor at Vermont Law School. Thanks so much for taking this time with us today, Pat, and happy Earth Day.

PARENTEAU: Happy Earth Day, Steve, to all of us. Thank you.

Related links:

- EPA’s Environmental Protection Timeline

- More about Pat Parenteau

- Click here to listen to our most recent segment with Pat Parenteau

[MUSIC: Nashville Mandolin Ensemble, “Where No Mandolin Has Gone Before – a/k/a Star Trek” on Plectrasonics, CMH Records]

Stories and Poetry for Earth Day

Liz Lat is a Minneapolis based student and writer. She is a Program intern at Climate Generation and a contributing writer to the 2020 Eyewitness: Storytelling Slam. (Photo: Courtesy of Liz Lat)

CURWOOD: Let’s take some time now to share poems and stories in this 50th-anniversary celebration of our connection to the Earth, and its protection. Writer Kao Kalia Yang brings us her essay “Delivery of My Boys”. Her twin boys are named Peace and Freedom

YANG: In early spring, Freedom and Peace raced each other across the spread of green lawn dotted with yellow plumes of dandelions. Freedom is ahead and Peace follows. They climb up high; they slide down low, they laugh and frolic in the open air. When I reach them, they run into my arms and tell me: we belong to you and to each other. They spread their arms wide and proclaim, we belong to the world. My heart, a mother's heart aches for the world that they belong to, even as it rejoices for a world that will know their laughter and their tears, the feel of their feet, the touch of their hands, the distance they represent between the past and future.

What led me to write this essay was a request to participate in a call for climate awareness, a celebration of Earth Day. I'm Hmong American, I am the descendant of shamans, medicine people, farmers. And so my people and my culture Hij have always had a really close relationship to the land. At the feet of my grandmother, I learned about the power of the plants, the power of the soil, the power of the rain. These are not lessons that I was taught in my American classroom so much. But these are the lessons of my home.

Kao Kalia Yang is a Minnesota based Hmong- American writer and public speaker. Her writing collection includes The Song Poet, and a children’s book titled A Map Into the World. She was a contributing writer and performer for the 2020 Eyewitness: Storytelling Slam Produced by Climate Generation. (Photo: Courtesy of Kao Kalia Yang)

Earth Day is for me a celebration of our ancestors, the people that we come from, and our descendants, you know, the ancestors who will one day be. It is this coming together to give thanks and gratitude for the shelter and the safety of the place and belonging.

I'm a refugee. I come from a world as my father says where the sky fell on us and where the earth threw us off. For a long time, I was a stateless child. But always I've always known I belong first and foremost to the earth and that no citizenship, no nationality could ever take that away from me. That from the moment of my birth, there was a place that I belong to and that place was a bigger world. And I think Earth Day is also a wonderful opportunity to be reminded. We live in a world where skies fall down and the earth itself throws us off, a world teeming with refugees, and that we belong because we belong first and foremost to each other.

LAT: My name is Liz Lat.

I am a first-generation Cambodian American and my parents were refugees. And I grew up with the horror stories of the Cambodian genocide, the Vietnam War, and it's a huge part of my identity. And what I didn't realize was that when they immigrated here to Minnesota, a huge part of their assimilation process was taking in the land. Getting into the culture of Minnesota that is the outdoors. And I just wanted to merge those two stories because I'm a born and raised Minnesotan, myself, and I love the North. I love the Boundary Waters. I love Lake Superior. I'm there every summer so I wanted to fuse, all of that emotion, all of that feeling the memories into one compiled story.

Earth Day is important to me and why I believe it's important for the world. It's because it's the one day we get to celebrate. I feel like, during climate change this climate crisis, we're always fighting and we are protesting, which is what we should do. Absolutely. But we have to remember what's already here.

What’s exiting the oceans, the mountains, the trees, it's home. It's what we live on. It's how we thrive. We are part of this whole connected life system, this web.

No matter how young you are, no matter how much you feel like you don't have a say in things, even educating your peers, educating your family, and just trying to tell stories is a form of protest. And to remember that you don't have to march on the streets if you don't want to. You can write your own story and you can share it. It's that simple.

Once upon a time, there was a daughter who was born in the state of Minnesota, the first generation of Khmer Americans. The spirit of the winter and the adventure of the summer allowed her to thrive throughout her childhood. She lived in a home full of cultural tradition and curiosity. She was taught to love and to be grateful and celebrate who she was since birth.

The great outdoors taught her more about life than the warmth and coziness of the fireplace inside. As a little girl, the heaviest snowstorms sparked a curious fire in her eyes; she was determined to strap on protective armor and build a snow kingdom beneath the pine tree in her backyard. In the summer, she woke up at the crack of dawn from her tent, raced to the docks, tackle box and fishing rod in hand, ready to catch the biggest of them all. It was these experiences, the memories that inspire the daughter to take care of the land she calls home, the home where her parents survived, and thrived.

Hearing the bedtime stories of the times past has driven her compassion to fight for social climate and justice and for the freedom of others. The daughter spends the rest of her life ensuring that no one feels alone, that even though the world feels dark and hopeless, she would be the light for those suffering. The girl spends 100 years spreading love to strangers and never stops using her voice. When she wakes, she marches with hope, and when she sleeps, she dreams of peace.

She stands with the earth she stands with her home.

BACIGALUPI: I’m Kathleen Bacigalupi, I’m a sixteen-year-old and I’m a Minnesota student, a part of YEA! MN, Youth Environmental Activists Minnesota.

YEA! MN activist Kathleen Bacigalupi (right) on a hike with her father. (Photo: Courtesy of Kathleen Bacigalupi)

When I was younger I went to Glacier National Park, and we went on this really beautiful hike and there was this super waterfall. A couple of years later we went back with a larger family group and we went on the same hike and it was very dry. And it kind of was alarming. And then the last few years we’ve had extreme polar vortexes in the winter, which canceled a bunch of schools, and then I got involved with YEA! MN and I started learning more about climate change and its impacts on all different kinds of communities; when we say “frontline communities”, I learned what that is. All of these things kind of made me realize that climate change isn’t just a planet issue, it’s a social justice issue, and I think that’s what got me really excited and motivated to fight for change.

I definitely don’t have a leadership role yet, like I’m not; I don’t consider myself like a face of the movement. But I’m learning that everyone has their own story. And I think this time is a good time for me to figure out how I can use mine, to benefit everyone else and the movement.

CURWOOD: That was Kathleen Bacigalupi, and before her, you heard Liz Lat and Kao Kalia Yang. We’ll close our ode to Earth Day with some free verse from Poet Chris Heeter.

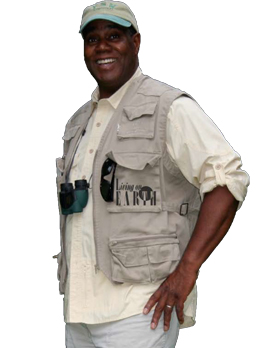

Chris Heeter is a professional speaker, wilderness guide, poet, and founder of the Wild Institute. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Heeter)

HEETER: This is called, “For the Earth Warriors…”

It used to be that weather was the thing you talked about–

at least in the Midwest–

when there was nothing else to say.

It followed ‘Hello’ and a mumbled ‘How ya doing’

with no expectation of a lengthy reply.

It quickly moved from there to temperatures, wind, or rainfall.

Something you could really sink your teeth into.

It had to do with altered outdoor plans

or rain needed for crops and gardens.

Here in the northland, it was about wind chill

and how the old-timers used to walk to school

in inclement weather without whining.

That sort of thing.

But these days, talk of weather has changed.

What was once unusual has become the norm.

Hurricanes, droughts, high and low temps—

all are off the charts we’ve faithfully kept all these years.

Indeed even habitats have changed.

What once supported moose, for example,

has shifted as temperatures climb

expanding the range of deer

bringing parasites and heat stress.

You know this already…or are quickly catching on.

What are we to do with what we know?

At best we feel a dull ache and concern

other times full-on foreboding.

Most of us channel this into the action of some kind—

at large or at home, we do what we can

and try to do more.

It’s frustrating and terrifying

but there is no temptation to look away.

We feel this in our bones as beings on this planet.

It is a deep inner knowing of something profoundly out of balance.

If this were a pretty poem, it would wrap up now

with something tidy and neat

about how we will find our Weh.

But this is a gritty poem that knows better.

It joins the chorus of millions upon millions

of voices, hearts, and souls

that cry out and will not look away.

So here it is, what I can offer is this…

in your darkest places and times

when your love and actions on behalf of all things Wild

feel not nearly enough,

remember you are not alone.

There are countless like-minded Wild souls here with you

also aware, also not willing to look away.

You can take heart in that.

We are a crafty lot.

And when you need to sigh or cry or fall apart

there are others here to help you pick up the pieces

and begin again. And again.

Until we tilt the circumstances

or die trying.

This beautiful world is worth it.

And you, Earth Warrior, are part of that beauty.

CURWOOD: That’s Chris Heeter with her poem, “For the Earth Warriors…”

Related links:

- About YEA! MN (Youth Environmental Activists Minnesota)

- Click here to learn more about Kao Kalia Yang’s work

- Click here to listen to bedtime stories of Khmer Americans by Liz Lat

- Click here to learn more about The Wild Institute and Chris Heeter

[MUSIC: Nashville Mandolin Ensemble, “Where No Mandolin Has Gone Before – a/k/a Star Trek” on Plectrasonics, CMH Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Candice Siyun Ji, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth