Siberian Heat Wave

Air Date: Week of July 3, 2020

Siberia is experiencing warmer-than-average temperatures for unusually long periods of time. (Photo: triplefivedrew, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0).

Siberia hit a record-high temperature of 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit on June 20, 2020 in the town of Verkhoyansk, though it is well north of the Arctic Circle. Dr. Susan Natali, Arctic Program Director at Woods Hole Research Center, discusses with Host Bobby Bascomb why the Far North is warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet, and the implications for the rest of the world.

Transcript

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in for Steve Curwood.

The town of Verkhoyansk in Siberia recently hit a record-high temperature of 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s the highest temperature ever recorded within the Arctic Circle, and it’s worrying scientists. For more I’m joined now by Susan Natali, Arctic Program Director at Woods Hole Research Center. Susan Natali, welcome to Living on Earth!

NATALI: Thank you very much.

BASCOMB: So as someone who studies this region, what were your initial thoughts when you saw this record high temperature in Verkhoyansk, Siberia?

NATALI: I was shocked at the magnitude of it. But perhaps not necessarily completely surprised to see these types of spikes in temperature, because this has been happening for a number of years now. The average temperature for June is 68 degrees Fahrenheit, so it's quite a bit warmer than the average.

BASCOMB: Yeah, gosh, I guess so. And I understand the Arctic is warming roughly twice as fast as the rest of the planet. Why is that?

NATALI: There's a number of reasons why warming is happening more in the Arctic, but one of the main ones has to do with regional effects or regional amplification. So, you know, if you think about what's happening with sea ice, and you think about what sea ice looks like, you see this very white surface where the sun's energy was reflected off. As the sea ice melts, and now you have this very dark surface, that does a better job of absorbing the sun's energy. And so that energy that's now in the water gets slowly released into the Arctic causing this regional amplifying effect.

BASCOMB: Sounds like a positive feedback loop where it's just going to create more and more warming in the future.

NATALI: Absolutely.

BASCOMB: And of course, the Arctic is home to much of the world's permafrost. That's ground that is permanently frozen all year. How are these unusually warm temperatures affecting the permafrost?

NATALI: So, these really high temperatures are placing the permafrost at risk. And so there's a couple of different ways that the permafrost is thawing. There's something that we call gradual thaw where the permafrost thaws from the top down. When we see these really extreme temperatures, it places the permafrost at risk of abrupt thaw or at higher risk of abrupt thaw, where you can get complete ground collapse. And say, in a single summer where now instead of thawing, you know, centimeters per year, we're talking meters to 10s of meters. The other thing that happens when you have these extremely warm summer months, the area gets very dry and you also place the region at risk of wildfire. And then wildfire in turn continues to place the permafrost at risk because it removes the insulation that the ground provides.

BASCOMB: Right, I recently read about a phenomenon called zombie fires in the Arctic. I mean, it sounds like a made up term but it's very real. What exactly is a zombie fire? What's going on there?

NATALI: Yeah, this is actually something that happens. So you can have a fire - there's so much organic matter below the ground that the fires in the Arctic don't just burn vegetation above ground, it burns peat in the organic material below ground. And that fire can last from one season - so you can see a fire burning in August and September below ground, and then it resurfaces early season in the spring, and it just had been smoldering throughout the winter below the ground.

Amidst the heatwave in the Arctic, wildfires are increasing in number and intensity. (Photo: Glenn Beltz, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Wow. And as you mentioned, the permafrost soil is basically peat, which I understand holds more carbon dioxide than all of the world's rainforests. I mean, that's a shocking statistic. So if the Arctic melts and releases that carbon, what does that mean for the world's carbon budget and climate change?

NATALI: Yeah, this is one of the big global concerns, or the big global concern related to permafrost thaw is, as you said, there's a lot of carbon that's stored below ground. That carbon currently isn't fully accounted for, those carbon losses aren't fully accounted for. So when we think about trying to stay below 1.5 degrees Celsius or 2 degrees Celsius, carbon emissions as a result of permafrost thaw is essentially going to use up anywhere from 25 to 40% of our remaining fossil fuel emissions budget. So it's going to make it really challenging to keep these temperature targets that were set out in these international climate agreements.

BASCOMB: I understand that Russia recently declared a state of emergency because of an oil spill linked to the melting permafrost. What happened there?

NATALI: The ground structure in the Arctic is maintained because there's frozen ground below it, but when the ice that's in the permafrost melts, you get ground collapse, you get subsidence, you can get very extreme, you know, abrupt events. But even gradual events is enough to cause cracks in a building, or to, you know, cause gas tanks or other types of infrastructure to fall and to crack, and this is what's happening in some areas of the Arctic. You know, this got a lot of attention because it was so big. But if you think about a community, even if it's just, you know, a community of 300 or 500 - that may not sound that big - when they're dealing with impacts to their important infrastructure like a sewage lagoon, or an oil storage tank or, you know, a city dump, you know, these human health risks are impacting Arctic communities in many places. And so even these other incidents that don't get these big headlines are really concerning because they are impacting people's cultures and their health and their livelihoods.

BASCOMB: Right. I would think even, you know, homes and buildings, places where people work, that the ground underneath them is literally shifting. I mean, it must wreak havoc on cities and towns.

NATALI: Yeah, it's wreaking havoc on cities and towns. And you even, you know, one of the things that struck me when I first started chatting with people from the Arctic is, those of us who don't live in the Arctic don't realize that people in the Arctic have to prop their houses up to level it. This is something I never would have thought of to do, I would have no idea how to do this, right? And people are talking about, oh, we used to have to do this once a year, and now we're having to do it three times a year or four times a year, and so these changes that are happening are becoming a part of people's daily lives. When we think about climate change, we often talk about what's going to happen in the future, we think about what's happening in 2100. And I think the important thing to think about with the Arctic is that this is actually something that's happening now. And there are people being impacted by this now. And there's infrastructure that's being impacted by this now. And so, you know, there's global implications for permafrost thaw, and there are feedbacks on global climate that may be happening now and expected to continue to happen into the future, but there's also these regional impacts, as you see ground collapsing on the people who are living in the Arctic.

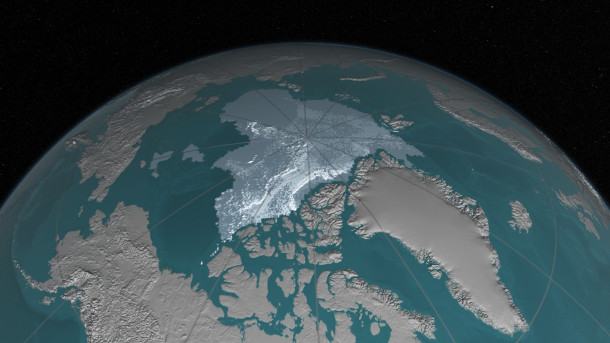

The Arctic Circle is warming roughly twice as fast as the rest of the world, causing permafrost to thaw at a rapid rate, impacting infrastructure and people’s livelihoods. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: And you've spent a lot of your career in the Arctic studying the region. What's the most striking change that you've noticed personally, in your time studying this area?

NATALI: I think last summer actually was the most striking. It wasn't a single change, but it was a series of changes across the landscape. You know, we were out in the tundra in July, and it was 90 degrees Fahrenheit. And so one, just feeling that temperature in the tundra is just, it's surprising, and there's no trees in the tundra, so you're just out and it's really, really warm. In addition to that, we saw lightning, which is something that is really not common in the tundra. In addition to that, there were wildfires in the area, so there was a lot of smoke around us. And then there was also a lot of ground cracking and ground collapse. And, you know, this was a region that had experienced wildfire in 2015. And so in the area, that experienced wildfire, the ground thaw was so extreme, it was double than what it had been in previous years. And you literally would walk in some places, and because the ground had, was collapsing because of permafrost thaw, because some of it had burned off in the fire, your foot would fall into the ground, like up to your knee. So it was just striking because it was a place that I knew, and to see that level and number of changes in a single year, I had never seen that. And I had never seen changes, so many changes in the landscape.

BASCOMB: So many different changes, and so fast. I mean, that seems to be the real, real problem here is the changes are happening so quickly. I mean, nothing can adapt - no plants, animals, people.

NATALI: Yeah. I don't like to think of it as insurmountable problem in that like, oh well, this is done and there's nothing we can do, right? Because, you know, one, the Arctic is a very large area and some regions have already undergone pretty extreme permafrost thaw. But sort of the actions that we take now in terms of our fossil fuel emissions will really have a big difference on how much of the Arctic will thaw and how many of these communities will be impacted, and, you know, how much economic costs there will be. So it's not an all or nothing situation in the Arctic. It's like recognizing like, yes, we've already bought in for some of these changes that are already happening that are going to happen. But like, let's act now and act soon to sort of reduce that impact for people in the Arctic and also globally.

BASCOMB: Susan Natali is an Associate Scientist and Arctic Program Director at Woods Hole Research Center. Susan, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

NATALI: Thank you so much for having me on your show, Bobby. Thank you.

Links

CNN | “Temperatures in an Arctic Siberian Town Hit 100 Degrees, a New High”

The Guardian | “Climate Crisis: Alarm at Record-Breaking Heatwave in Siberia”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth