July 3, 2020

Air Date: July 3, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Siberian Heat Wave

View the page for this story

Siberia hit a record-high temperature of 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit on June 20, 2020 in the town of Verkhoyansk, though it is well north of the Arctic Circle. Dr. Susan Natali, Arctic Program Director at Woods Hole Research Center, discusses with Host Bobby Bascomb why the Far North is warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet, and the implications for the rest of the world. (08:57)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Bobby Bascomb discuss the politicization of the public health practice of wearing masks. Then, the oil and gas industries face major contractions as countries impose travel restrictions to slow the spread of the coronavirus. Finally, Peter and Bobby take a look back at shark, sewage and medical waste scares along the New Jersey coast. (04:41)

EPA Approves GMO Mosquito Trials

View the page for this story

Biotech company Oxitec is developing genetically modified mosquitoes in hopes of reducing local populations of mosquitoes that carry dengue fever, yellow fever, and the zika virus. Now the Environmental Protection Agency has given Oxitec the go-ahead to test the effectiveness of these GMO mosquitoes in parts of Florida and Texas. Dr. Natalie Kofler, founder of the bioethics group Editing Nature, speaks with Host Bobby Bascomb about how the genetic modification is designed to work and why it is generating concerns. (09:08)

Court Finds EPA Violated Pesticide Safety Procedures

View the page for this story

In 2018, the Environmental Protection Agency approved a new, broader use of Dicamba, a powerful herbicide. But a federal appellate court recently found EPA did not adequately consider risks and problems, including costs to farmers who do not use the chemical or who don’t want to buy seeds of genetically modified crops that can tolerate it. Lori Ann Burd, Environmental Health Program Director and a Senior Attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about the court’s ruling. (09:48)

Dancing with Bees: A Journey Back to Nature

View the page for this story

The innate curiosity about and connection to the natural world that many of us experience as children are often lost on the path to adulthood. Brigit Strawbridge Howard, author of Dancing with Bees: a Journey Back to Nature, found her way back to a childlike fascination with nature with the help of some of the world's most important pollinators: honeybees, bumblebees, and oft-overlooked solitary bees. Brigit joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss the fascinating habits of solitary bees, how to help diverse bee species thrive in your own backyard, and how best to reconnect with nature. (14:37)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Lori Ann Burd, Brigit Strawbridge Howard, Natalie Kofler, Susan Natali

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb

A federal court rules against the EPA in its approval of a controversial herbicide.

BURD: It's been a catastrophic few years, and that was one of the things that the court really highlighted multiple times in this decision. They said EPA failed to consider how Dicamba was damaging the social fabric of rural communities.

BASCOMB: Also, there are some 20,000 species of bees in the world, and we’ll have some tips to help those near you.

HOWARD: One of the most beautiful things we can do, and maybe this is where I would start, is get out in your backyard, or your garden, or your plot, and look and notice and watch and observe, and get to know the insects that you already have there.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Siberian Heat Wave

Siberia is experiencing warmer-than-average temperatures for unusually long periods of time. (Photo: triplefivedrew, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0).

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in for Steve Curwood.

The town of Verkhoyansk in Siberia recently hit a record-high temperature of 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s the highest temperature ever recorded within the Arctic Circle, and it’s worrying scientists. For more I’m joined now by Susan Natali, Arctic Program Director at Woods Hole Research Center. Susan Natali, welcome to Living on Earth!

NATALI: Thank you very much.

BASCOMB: So as someone who studies this region, what were your initial thoughts when you saw this record high temperature in Verkhoyansk, Siberia?

NATALI: I was shocked at the magnitude of it. But perhaps not necessarily completely surprised to see these types of spikes in temperature, because this has been happening for a number of years now. The average temperature for June is 68 degrees Fahrenheit, so it's quite a bit warmer than the average.

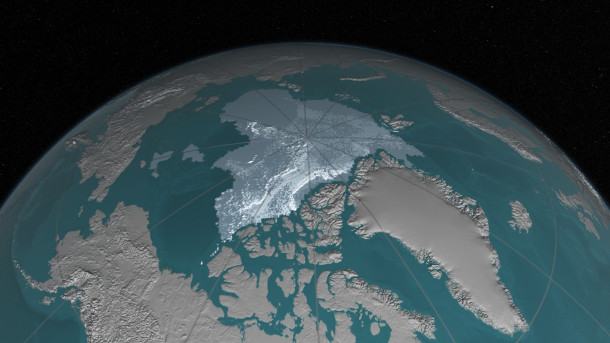

BASCOMB: Yeah, gosh, I guess so. And I understand the Arctic is warming roughly twice as fast as the rest of the planet. Why is that?

NATALI: There's a number of reasons why warming is happening more in the Arctic, but one of the main ones has to do with regional effects or regional amplification. So, you know, if you think about what's happening with sea ice, and you think about what sea ice looks like, you see this very white surface where the sun's energy was reflected off. As the sea ice melts, and now you have this very dark surface, that does a better job of absorbing the sun's energy. And so that energy that's now in the water gets slowly released into the Arctic causing this regional amplifying effect.

BASCOMB: Sounds like a positive feedback loop where it's just going to create more and more warming in the future.

NATALI: Absolutely.

BASCOMB: And of course, the Arctic is home to much of the world's permafrost. That's ground that is permanently frozen all year. How are these unusually warm temperatures affecting the permafrost?

NATALI: So, these really high temperatures are placing the permafrost at risk. And so there's a couple of different ways that the permafrost is thawing. There's something that we call gradual thaw where the permafrost thaws from the top down. When we see these really extreme temperatures, it places the permafrost at risk of abrupt thaw or at higher risk of abrupt thaw, where you can get complete ground collapse. And say, in a single summer where now instead of thawing, you know, centimeters per year, we're talking meters to 10s of meters. The other thing that happens when you have these extremely warm summer months, the area gets very dry and you also place the region at risk of wildfire. And then wildfire in turn continues to place the permafrost at risk because it removes the insulation that the ground provides.

BASCOMB: Right, I recently read about a phenomenon called zombie fires in the Arctic. I mean, it sounds like a made up term but it's very real. What exactly is a zombie fire? What's going on there?

NATALI: Yeah, this is actually something that happens. So you can have a fire - there's so much organic matter below the ground that the fires in the Arctic don't just burn vegetation above ground, it burns peat in the organic material below ground. And that fire can last from one season - so you can see a fire burning in August and September below ground, and then it resurfaces early season in the spring, and it just had been smoldering throughout the winter below the ground.

Amidst the heatwave in the Arctic, wildfires are increasing in number and intensity. (Photo: Glenn Beltz, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Wow. And as you mentioned, the permafrost soil is basically peat, which I understand holds more carbon dioxide than all of the world's rainforests. I mean, that's a shocking statistic. So if the Arctic melts and releases that carbon, what does that mean for the world's carbon budget and climate change?

NATALI: Yeah, this is one of the big global concerns, or the big global concern related to permafrost thaw is, as you said, there's a lot of carbon that's stored below ground. That carbon currently isn't fully accounted for, those carbon losses aren't fully accounted for. So when we think about trying to stay below 1.5 degrees Celsius or 2 degrees Celsius, carbon emissions as a result of permafrost thaw is essentially going to use up anywhere from 25 to 40% of our remaining fossil fuel emissions budget. So it's going to make it really challenging to keep these temperature targets that were set out in these international climate agreements.

BASCOMB: I understand that Russia recently declared a state of emergency because of an oil spill linked to the melting permafrost. What happened there?

NATALI: The ground structure in the Arctic is maintained because there's frozen ground below it, but when the ice that's in the permafrost melts, you get ground collapse, you get subsidence, you can get very extreme, you know, abrupt events. But even gradual events is enough to cause cracks in a building, or to, you know, cause gas tanks or other types of infrastructure to fall and to crack, and this is what's happening in some areas of the Arctic. You know, this got a lot of attention because it was so big. But if you think about a community, even if it's just, you know, a community of 300 or 500 - that may not sound that big - when they're dealing with impacts to their important infrastructure like a sewage lagoon, or an oil storage tank or, you know, a city dump, you know, these human health risks are impacting Arctic communities in many places. And so even these other incidents that don't get these big headlines are really concerning because they are impacting people's cultures and their health and their livelihoods.

BASCOMB: Right. I would think even, you know, homes and buildings, places where people work, that the ground underneath them is literally shifting. I mean, it must wreak havoc on cities and towns.

NATALI: Yeah, it's wreaking havoc on cities and towns. And you even, you know, one of the things that struck me when I first started chatting with people from the Arctic is, those of us who don't live in the Arctic don't realize that people in the Arctic have to prop their houses up to level it. This is something I never would have thought of to do, I would have no idea how to do this, right? And people are talking about, oh, we used to have to do this once a year, and now we're having to do it three times a year or four times a year, and so these changes that are happening are becoming a part of people's daily lives. When we think about climate change, we often talk about what's going to happen in the future, we think about what's happening in 2100. And I think the important thing to think about with the Arctic is that this is actually something that's happening now. And there are people being impacted by this now. And there's infrastructure that's being impacted by this now. And so, you know, there's global implications for permafrost thaw, and there are feedbacks on global climate that may be happening now and expected to continue to happen into the future, but there's also these regional impacts, as you see ground collapsing on the people who are living in the Arctic.

The Arctic Circle is warming roughly twice as fast as the rest of the world, causing permafrost to thaw at a rapid rate, impacting infrastructure and people’s livelihoods. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: And you've spent a lot of your career in the Arctic studying the region. What's the most striking change that you've noticed personally, in your time studying this area?

NATALI: I think last summer actually was the most striking. It wasn't a single change, but it was a series of changes across the landscape. You know, we were out in the tundra in July, and it was 90 degrees Fahrenheit. And so one, just feeling that temperature in the tundra is just, it's surprising, and there's no trees in the tundra, so you're just out and it's really, really warm. In addition to that, we saw lightning, which is something that is really not common in the tundra. In addition to that, there were wildfires in the area, so there was a lot of smoke around us. And then there was also a lot of ground cracking and ground collapse. And, you know, this was a region that had experienced wildfire in 2015. And so in the area, that experienced wildfire, the ground thaw was so extreme, it was double than what it had been in previous years. And you literally would walk in some places, and because the ground had, was collapsing because of permafrost thaw, because some of it had burned off in the fire, your foot would fall into the ground, like up to your knee. So it was just striking because it was a place that I knew, and to see that level and number of changes in a single year, I had never seen that. And I had never seen changes, so many changes in the landscape.

BASCOMB: So many different changes, and so fast. I mean, that seems to be the real, real problem here is the changes are happening so quickly. I mean, nothing can adapt - no plants, animals, people.

NATALI: Yeah. I don't like to think of it as insurmountable problem in that like, oh well, this is done and there's nothing we can do, right? Because, you know, one, the Arctic is a very large area and some regions have already undergone pretty extreme permafrost thaw. But sort of the actions that we take now in terms of our fossil fuel emissions will really have a big difference on how much of the Arctic will thaw and how many of these communities will be impacted, and, you know, how much economic costs there will be. So it's not an all or nothing situation in the Arctic. It's like recognizing like, yes, we've already bought in for some of these changes that are already happening that are going to happen. But like, let's act now and act soon to sort of reduce that impact for people in the Arctic and also globally.

BASCOMB: Susan Natali is an Associate Scientist and Arctic Program Director at Woods Hole Research Center. Susan, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

NATALI: Thank you so much for having me on your show, Bobby. Thank you.

Related links:

- CNN | “Temperatures in an Arctic Siberian Town Hit 100 Degrees, a New High”

- The Guardian | “Climate Crisis: Alarm at Record-Breaking Heatwave in Siberia”

- Common Dreams | “‘This Scares Me,’ Says Bill McKibben as Arctic Hits 100.4°F—Hottest Temperature on Record”

[MUSIC: Amira Medunjanin & Trondheim Solistene, “Sve pticice zapevale” on Ascending, traditional/arr. Ante Gelo, Town Hill Records]

Beyond the Headlines

A child wears a protective face mask during the Coronavirus pandemic. (Photo: Nik Anderson, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News--that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi Bobby, you know, and all the political swirl and the blanket coverage of coronavirus and the economic impacts of coronavirus. We've also gotten an opportunity to watch a twisted cousin of climate denial take hold. Disease denial, COVID-19 denial, whatever you want to call it, has people out there that view not wearing a mask in defiance of state orders as an act of patriotism. And in states like my own state, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Texas, states that have reopened their societies too quickly, are now seeing COVID deaths and diagnoses increase,

BASCOMB: Right, it's really strange, but somehow wearing a mask or not has become a political statement. And now Just a prudent health measure. But of course the virus doesn't discriminate if you're a Republican or a Democrat. Well, what else do you have for us this week, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Something that was pointed out to me by an article in the online magazine Quartz, oil and gas companies may be set to lose a trillion dollars or more in revenues. This year, the oil and gas industry, including all of the major oil companies, made 2.47 trillion in revenues last year, in 2019. This year, it by some estimates may be only a trillion, or maybe a trillion and a half, which gets to be real money.

The oil industry has struggled during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly due to declining demand for gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel. (Photo: Jonathan Cutrer, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Hmm. So they've lost about half their value?

DYKSTRA: Possibly as much as half their value. Contrast that to a company like Apple. Apple's worth about a third of a trillion. They haven't passed the oil and gas industry yet, but the momentum for both is clear. Oil and gas is slowly dying off and software companies are constantly growing. And at some point, Apple is going to catch up to Exxon Mobil, BP, Texaco, and all the other companies that have driven not only our economy, but our international policies for almost literally the last century.

BASCOMB: Hmm. Well, you're comparing apples to petroleum here, though. I mean, how fair is that? Really?

DYKSTRA: There's a zinger for you, Bobby. It may be very, very fair in the near future. And it's something we'll be looking for. The clean energy sector, wind and solar, they've got a much, much longer way to catch up to oil and gas, but the momentum is clear.

BASCOMB: All right. Well, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: We're gonna do a special Jersey edition in honor of my home state, and go back to 1916. The US hadn't even entered World War I yet, but there were attacks along the Jersey shore, specifically by sharks against humans. And 60 years later, that string of attacks that terrorized, much of the East Coast and certainly New Jersey became the inspiration for Peter Benchley's book, and the movie Jaws, one of the biggest, most successful movies of all time.

BASCOMB: Yeah, that one's still frightens people, I think to some degree or certainly has given sharks a bad reputation in pop culture.

DYKSTRA: Sharks have some really bad PR, but so did New York City for dumping sewage sludge off the Atlantic coast. They formally ended that practice on June 30, 1982. Fast forward to five years later, medical waste started washing up on the beaches of New Jersey that lasted through the 1988 summer season. And it became an impetus to better enforce and strengthen ocean pollution and water pollution laws around the country.

A biplane flies over beachgoers on the New Jersey shore. (Photo: Raymond Bucko, SJ, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Wow. 1982 and 88. I mean, that's not that long ago to be dumping medical waste and raw sewage into the ocean off one of the most populated cities in the country.

DYKSTRA: Right? And if you consider that 1988 was when James Hansen really sounded the alarm that the public first heard about climate change. And, look, we're here 32 years later, and climate denial, along with coronavirus denial, still sits in the White House.

BASCOMB: All right. Well, thank you. Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Bobby. Thanks a lot, talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “The Battle Over Masks in a Pandemic: An All-American Story”

- Houston Chronicle | “Reporter’s Notebook: Oil and Gas Facing Its Own ‘Energy Apocalypse’”

- Environmental Health News | “Ode to Jersey”

[MUSIC: Juan Pablo Dobal & Gustavo Toker, “Milonga de mis amores” on World Music In the Netherlands: Tango, by P. Laurenz, Radio Netherlands]

BASCOMB: Coming up – EPA approves field trials in Florida for a controversial genetically engineered mosquito. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Juan Pablo Dobal & Gustavo Toker, “Milonga de mis amores” on World Music In the Netherlands: Tango, by P. Laurenz, Radio Netherlands]

EPA Approves GMO Mosquito Trials

Oxitec’s second generation “AA” friendly mosquitoes are genetically engineered so that all female offspring die at the larval stage. The females are the ones that bite and thereby spread disease from their saliva. (Photo: Courtesy of Oxitec Ltd.)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

[SFX MOSQUITO SOUND]

BASCOMB: No one likes mosquitoes, the annoying buzzing in our ears, the itchy bites they bring and of course the diseases they can transmit. In fact, some three quarters of a million people die each year from mosquito borne illnesses, indirectly making the lowly insect responsible for more human deaths than any other animal in the world. So, it’s not shocking that humans try to control mosquito populations. And now researchers with the biotech company Oxitec have come up with a genetically engineered mosquito that they hope will reduce mosquito populations without using ecologically damaging pesticides. Oxitec recently received EPA approval for their first US field trials in the Florida Keys this summer and Harris County, Texas next year. But the approval is controversial and has garnered push back from ethicists and molecular biologists including Natalie Kofler. She’s founding director of Editing Nature, a working group on the ethics of genetic modification and an advisor for the Scientific Citizenship Initiative at Harvard Medical School. Natalie Kofler, welcome to Living on Earth!

KOFLER: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

BASCOMB: So Oxitec is focusing on a genetic solution to control a specific species of mosquito, why are they starting there?

KOFLER: Yeah, so the mosquito that they're targeting is the species called Aedes aegypti. And the way that they're they've made a genetically modified version of this mosquito is they've introduced a gene into the mosquito that when it makes in the wild, it will pass on a gene to its offspring that causes lethality or death in the female offspring of that mosquito. In this way, all female mosquitoes from those meetings will die. And over time, as you can imagine, if there aren't females around, the population will collapse. So the intention is to reduce local mosquito populations. And in doing that be able to then hopefully reduce transmission of the diseases they carry.

Dr. Natalie Kofler is the founding director of Editing Nature, a working group on the ethics of genetic modification, as well as an adviser for the Scientific Citizenship Initiative at Harvard Medical School. (Photo: Courtesy of Natalie Kofler)

BASCOMB: And they recently got EPA approval to release some of their patented mosquitoes at sites in Florida and Texas. What are they trying to do there and how likely is it to be allowed to move forward?

KOFLER: So really what the EPA here is allowing Oxitec to do is release their mosquitoes into the wild and test to see if they are actually able, with their genetically modified mosquitoes, to reduce the population Aedes aegypti in those locations. But this is really a landmark decision. It's the first time a genetically modified mosquito has been approved for release in the United States. Oxitec did attempt to do this already in 2016 and 2017, in trying to release a previous version of this mosquito. And they actually were eventually rescinded their request, because of public pushback within the communities in Florida, where they were trying to release. So this is sort of their second attempt of doing this. And it's something that we're watching really, really closely to make sure that this moves forward in a responsible way.

BASCOMB: And what was the pushback from residents in Florida at the time?

KOFLER: I mean, generally concerns is probably what anyone would sort of be concerned about the idea of a genetically modified organism and being sort of the first test site in the US where that would be released into your into your common environments, right. There's no way to do these field trials in a contained way. The mosquitoes are literally you know, sent out into the air and fly around and are sent out to mate with other wild mosquitoes. And so people had a variety of concerns both for their own health as well as for the health of the environment. Of course, there's concerns at that point of what happens if a genetically modified mosquito were to bite me, you know, is there any risk to me, or an allergenic risk if a GM mosquito were to bite? This new strategy that they're using is a bit different because only female mosquitoes are able to bite and Oxitec's new version of this mosquito exclusively with releasing males. So there shouldn't be any risk there if it works as expected. And then, of course, there was also a lot of concerns around potential ecological damage. You know, what happens when you start collapsing populations in the wild in this way? So there's a lot of uncertainty here. And I think that's really the main sort of underpinning of why people have a lot of concerns. We just don't know enough yet about how this would work in the wild.

BASCOMB: What sorts of rules are in place for testing and oversight before these modified mosquitoes are released into the environment?

KOFLER: Well, so Oxitec you should know has already been releasing these mosquitoes for over a decade, at least certain versions of them, in Brazil and other countries in South America. So, we would not be the first site where release has occurred. And they have been doing assessment of these mosquitoes to see whether or not for example, they integrate into the wild as they shouldn't, to see if they can see collapse of the populations, they do see collapse of the populations. However, they have yet to prove any reduction in say Dengue fever transmission in Brazil, where they were doing field trials. And so, there are some preliminary data that shows that this technology could be effective in reducing mosquito populations. What we have concerns about is that there isn't necessarily adequate data about around ecosystem impacts, really adequate, stringent studies on potential health impacts and the changes in vector capacity that happens when these mosquitoes are specifically targeted through a genetically modified technology. And the third concern and a really major one is a lot of the data that's being presented to say the EPA in this case has been accumulated assessed and experiments designed by Oxitec themselves. So there's very little data coming from third party independent researchers.

A capsule of GM Mosquito eggs held by an Oxitec scientist. The tests in Florida are for release from boxes spread in strategic locations (sometimes in human populated areas), and Oxitec is developing egg capsules for more efficient releases. Continuous release is required to prevent recolonization by the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. (Photo: Courtesy of Oxitec Ltd.)

BASCOMB: So you're concerned then that maybe there's not enough oversight, not enough independent oversight for this?

KOFLER: Yeah, I'm concerned that there's not enough independent oversight. I'm concerned that there's not enough interdisciplinary oversight. You know, these are really complex decisions that are being made. You need to have ecologists, you need to have public health experts, you need to have vector biologists, you need to have ethicists, and geneticists all at the table to make these choices. And so I also have concern that there isn't even the broad amount of expertise that needs to be there. And of course, it's also concerning when it's a, when it's a for profit company. And in some ways, they have a lot of vested interest to make sure that they do this well and safely or that, and they, because they could lose a lot of money and they could lose, you know, trust in their product. But at the same time, it leads to a lot of opacity in this process. And so I think that's concerning as well is that it needs to be more transparent and there's a lot of parts of the EPA submission that the public is generally not allowed to access because it's, you know, under patent protection and things like that. So there's a really strong justice argument here where those people that live in those environments have the right to the decisions that are being made about release of genetically modified mosquitoes into their communities. And right now, our regulatory processes do not engage the public even close to the level that they should be to make these choices fairly.

BASCOMB: What about the ecological impacts of suddenly reducing the population of a species of mosquito? I mean, plenty of birds and bats rely on mosquitoes as part of their diet. And I've heard of some species of orchids that are only pollinated by mosquitoes.

KOFLER: The general belief is that there are you know, in the world there's thousands of different mosquito species and even in these locations where the Aedes aegypti GM mosquito would be trialed, there are other mosquito species present. So the idea is that you could have other mosquito species fill those voids in a way that may actually in some ways if it could be done safely more environmentally sustainable than sort of doing broad application of pesticide for example, which would kill all mosquitoes and perhaps many other insects as well. So there's the possibility that if it's done well, it could actually be a more environmentally responsible measure. Again, this comes back to the situation of just how little we still know. And there's a lot of uncertainty. And I think we need to be understanding the unknown risks, you know, or at least acknowledging the unknown risks of what could happen when you start messing with food networks this way. And I think the second issue that needs to be really strongly considered, you know, with this appreciation of the intricate link between environmental health and human health, you know, is what happens when you specifically target one vector of a disease is another vector going to step in another mosquito species that may be more difficult to control that might be even more able to spread the disease more easily, and be more virulent. And these are really major concerns that again, we still don't have have the answers to.

Dr. Nathan Rose is Head of Regulatory Affairs at Oxitec. (Photo: Courtesy of Oxitec Ltd.)

BASCOMB: Natalie Koffler is a molecular biologist and founding director of Editing Nature. Natalie, thank you for taking this time with me today.

KOFLER: Thanks so much for having me.

BASCOMB: For a response we spoke with Nathan Rose, Head of Regulatory Affairs with Oxitech. He told our producer that the EPA reviewed thousands of pages of data Oxitech submitted to them.

ROSE: The EPA is independent. EPA is a government agency. And so they are the primary reviewers of this technology and of any technology that's it calls itself a pesticide or a bio pesticide as this is. And so EPA scientists that worked on this, included molecular biologists, they included ecologists, they included experts in modeling of what happens to populations.

BASCOMB: To hear more of Mr. Rose’s response go to the Living on Earth website, LOE dot org.

Statement from Oxitec

"We are delighted with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) decision to grant Oxitec an Experimental Use Permit (EUP) for piloting its 2nd generation Friendly™ Aedes aegypti mosquito technology, the result of an in-depth and rigorous scientific review process that included technical support from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and an expansive assessment of the technology and its safety relating to humans and the environment. The EPA’s positive findings are fully consistent with findings by regulators and public health officials around the world who have approved of and validated Oxitec technologies as safe and self-limiting over the past 15 years."

For more, click the links below.

Related links:

- Click here for Oxitec’s press release from the May 1st announcement of EPA approval of the pilot project

- Click here for Oxitec’s press release from the June 15th announcement of Florida state regulatory approval of the project

- The Guardian | “Plan to Release Genetically Modified Mosquitoes in Florida Gets Go-Ahead”

- The Boston Globe | “Before Genetically Modified Mosquitoes Are Released, We Need a Better EPA”

- Read the EPA’s statement on the approval, and accompanying public comments here

- Click here to listen to Living on Earth’s segment on genetic engineering of mosquitos from 2012

[MUSIC: Michael Martin Murphey, “Texas Trilogy: Daybreak” on Austinology – Alleys Of Austin, by Michael Martin Murphey, Soundly Music/Horsefly Productions]

Court Finds EPA Violated Pesticide Safety Procedures

A study published in May 2020 from the National Institutes of Health linked the herbicide dicamba to the increased likelihood of developing one of several kinds of cancer. (Photo: cjuneau, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Genetic modification is often controversial in agriculture, especially when it is bundled with pesticide use. In 2018, the Environmental Protection Agency approved the herbicide Dicamba for its use on cotton and soybean plants genetically engineered to survive its application. But on June 3rd of this year, a federal appeals court in San Francisco ruled that the EPA ignored evidence of risk posed by the chemical and did not have enough evidence to support its approval. The court banned farmers from spraying Dicamba and companies from selling it. Four organizations filed the petition that led to that decision, including the Center for Biological Diversity. Lori Ann Burd is Environmental Health Program Director and a Senior Attorney with the Center.

She spoke with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: So tell me about Dicamba, this pesticide that the court ruled on, how does it work?

BURD: Well, Dicamba is a decades-old herbicide. It hadn't been very popular for a while because it is notoriously drift-prone, and it's also highly volatile. So it doesn't do a very good job at staying where it's supposed to stay. Typically, if you spray a plant with a herbicide, it kills the plant. And so it hadn't been in very widespread use. But just a few years ago, Monsanto and some others requested that EPA approve its use for genetically engineered soybeans and cotton that are designed to withstand what would normally be a fatal, over-the-top use of the herbicide. These are genetically engineered so that you can spray them with the herbicide and they won't die from it.

CURWOOD: So when you say that Dicamba is drift-prone, just how far does it and what does it do when it gets there?

BURD: So Dicamba can drift for miles in the right conditions. And when it gets to the new location, it kills plants. It's an herbicide. So it's designed to kill plants. And so that's why it's had so much controversy around it because when it drifts and then volatilizes again, it is killing plants that it's not intended to be coming in contact with.

CURWOOD: What are the health effects of Dicamba?

BURD: So the National Institute of Health put out a study in May finding that the use of Dicamba can increase the risk of developing multiple cancers, including liver cancer, bile duct cancer, acute and chronic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma. So this is also not a benign herbicide for humans.

CURWOOD: So what was the experience of the agricultural community with Dicamba being used this way?

BURD: It's been a catastrophic few years, and that was one of the things that the court really highlighted multiple times in this decision. They said EPA failed to consider how Dicamba was damaging the social fabric of rural communities. There were thousands of complaints and farmers are not the complaining type. And so if they're calling their state Departments of Agriculture and saying my non-Dicamba tolerant crops have all been damaged, I've lost my garden, my trees have been killed. That's really significant. There was a murder over use of Dicamba that the court talked about. A neighbor murdered their neighbor because one neighbor complained about the Dicamba use and the neighbor who they were complaining to killed them.

Dicamba has been especially criticized due to its tendency to spread and damage crops in neighboring fields. (Photo: Aqua Mechanical, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So let's go back to this recent case. What exactly was the decision that the Environmental Protection Agency made about Dicamba-based pesticides in 2018?

BURD: So they reapproved the Dicamba formulas for over-the-top use on cotton and soybeans at that time. They had approved it previously and we sued over that first approval also. And then EPA mooted that first lawsuit, which a decision was pending on by issuing a new decision.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about the statute here that this was done by the EPA. This is the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act. It's known by its acronym, FIFRA. Just how much power does the EPA have under this law?

BURD: It gives them an enormous amount of power and discretion. So unlike other environmental laws, like the Clean Water Act, or the Clean Air Act that have firm benchmarks, the test under FIFRA is whether there are unreasonable adverse effects. So FIFRA requires EPA to do a cost-benefit analysis of new pesticide applications. So they asked them to look at you know, what are the benefits? Growers want a new herbicide product to use for whatever reason, they have weeds. What are the costs? Are there significant environmental costs, social costs economic costs? So what the court found here is that EPA both ignored information about the harms that Dicamba was causing, and it minimized the harms that it did acknowledge. And in doing that cost-benefit analysis, the court found that they both discounted the damage that they were hearing about--that they knew about--in their analysis, and they refused to consider a lot of damage that they should have considered.

CURWOOD: To what extent does this ruling touch on the economic aspects of this case?

BURD: So on the economic impacts, what they looked at was harm to neighboring farms and other entities that experienced drift like resorts, home garden growers, people like that. And they also looked at the anti-competitive impacts of Dicamba, meaning that many growers who did not want to grow the Dicamba-tolerant soybean, were forced to buy the Dicamba-tolerant soybean seeds so that drift from their neighbor's Dicamba use would not kill their soybeans. This forced them to buy a product they did not want, they shouldn't have needed and they had to spend more money on which was unfair.

CURWOOD: So why do you think the EPA made the decision to approve Dicamba-based herbicides in the first place?

BURD: EPA's pesticide office, the Office of Pesticide Programs, has been in the pocket of the pesticide industry for quite a while now. Sadly, this was you know, the office that came out of the legacy of Rachel Carson to protect humans and the environment from dangerous chemicals that weren't being properly evaluated. But they've really taken a turn to being a rubber stamping agency for industry. Even when Dicamba was first proposed for this use, there was broad opposition. Agricultural experts, professors, agronomists--they all said this is going to be too dangerous. And you know, sometimes it's terrible to be right, and this is one of those instances.

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the EPA had substantially understated the risks that dicamba herbicides pose. (Photo: Ken Lund, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: There's been a lot of coverage on farmers who had planted their crops earlier this year with Dicamba-resistant crops. And now if they follow the law, they can't use that as an herbicide to weed their plantings. So what does this really mean for those farmers and their crops, do you think?

BURD: This means that, once again, they've been let down by EPA and the pesticide industry. This is a crisis manufactured by them. In 2018, we were on the cusp of getting a decision from the court and instead they issued a new decision moving out that ruling and so we couldn't get certainty on what was going to happen on Dicamba then. We filed a new lawsuit on an expedited schedule. EPA took from January until summer of 2019 just to produce a small administrative record. The point I'm making is that if they had not issued a new decision in the winter time before growers made seed-purchasing decisions, if they had not delayed oral argument, it could have been issued much earlier in the season.

CURWOOD: So this ruling by the appeals court sounds like a pretty big slap in the face for the Environmental Protection Agency. What does it mean for this organization and how it has operated under FIFRA, the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act?

BURD: EPA has been ignoring its mandate to protect human health and the environment. And this needs to stop. And in this rebuke, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals made abundantly clear that they recognized the fact that growers were forced to buy a product they did not want to buy in order to avoid the damage. But that would benefit industry because they were buying that product. EPA ignored all those things and it's been ignoring the real world harms the pesticides are causing to communities, to our land, to our health to animals for far too long. I do think, going forward, this decision is a powerful spotlight on how much this office needs to change and how urgently reform is needed to our pesticide law, how we need regulators in place that are going to care about protecting human health and the environment from pesticides, and not just regulators who are willing to bend over backwards to give the pesticide industry, whatever it wants, no matter what the cost.

BASCOMB: That’s Lori Ann Burd, the Environmental Health Program Director and a Senior Attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity speaking with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

The EPA recently clarified that farmers who have already purchased Dicamba for this year will be able to use it until the end of July. We reached out to EPA for a response to this story. They sent a statement which reads in part,

“EPA stands by its order and will vigorously defend against attempts to limit the Agency’s authority to provide clarity and certainty to farmers.”

BASCOMB: The full statement is available on the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch | “Court Rules Dicamba Illegal on Crops. Bayer Stands to Lose Millions”

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch | “EPA Says Farmers Can Use Existing Supplies of Dicamba Even Though a Court Blocked Sales and Use of the Weedkiller”

- NPR Short Wave | “The Fight Over a Weedkiller, in the Fields and in the Courts”

[MUSIC: Edgar Meyer and Tamara-Anna Cislowska, “McGlynn’s Jigs” by Edgar Meyer and Arty McGlynn]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Dancing with Bees, an author reconnects with nature by studying the fascinating lives of bees in her own garden. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ruby Braff, “I Got Rhythm” on Ruby Braff (The Concord Jazz Heritage Series), by George Gershwin/Ira Gershwin, Concord Records]

Dancing with Bees: A Journey Back to Nature

The United States has over 4,000 species of native bees, the majority of which are solitary bees. (Photo: Jonas Rösing, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

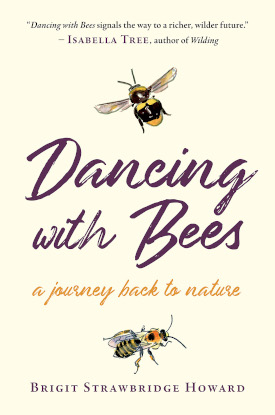

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb. As children, most of us are innately curious about the natural world. But on the way to adulthood that curiosity and connection are often lost. When author Brigit Strawbridge Howard realized she wanted to recapture her childhood connection to nature she chose the humble bee as ambassador to the world she wanted to explore. In her book Dancing with Bees: a Journey Back to Nature, Brigit describes how she learned to notice the world around her by paying special attention to the honeybees, the bumblebees, and solitary bees that buzzed right through her garden and into her heart. And she joins me now. Brigit – welcome to Living on Earth!

HOWARD: Thank you. Thank you so much for inviting me.

BASCOMB: In your journey to learn about bees, you learned a lot. I mean, there are thousands of different species of bees, as you mentioned, and many of us probably just think of honey bees, maybe bumble bees, but how many species are there and, and what you know, really sets them apart from each other?

HOWARD: Okay, well on planet Earth, there are some 20,000 to 25,000 different species. And those are just the ones that have been recorded, you know, and described, and I think you have about 4,000 species in North America alone. And I think about nine of those are honeybees. Plus there are some subspecies and there are around 250 different species of bumblebee and the rest are solitary bees. Broadly speaking, you can divide these bees between those that are social, truly social, that's the honeybees and the bumblebees, and those that are not fully social. Some of them have social traits, but some of them are like single mums. Social insects have a queen. And they have sometimes tens of thousands of workers in a colony and they have males. And there is a division of labor. But there's also cooperative care of the young. So that doesn't happen with solitary bees. And the majority of the bees on this planet are solitary. And it's only the honeybees that make honey, hence the name honeybees. I think that's, that's one of the first things. Bumblebees collect nectar and store nectar to feed their young, but they're not alchemists like honeybees, they don't turn it into honey. And it's the solitary bees that I have found most fascinating, more because of their nesting behavior than anything else.

BASCOMB: Well, how do they nest that sets them apart?

Dancing with Bees: A Journey Back to Nature is about naturalist Brigit Strawbridge Howard’s desire to recapture the connection with the natural world that she felt as a child. (Photo: Courtesy of Chelsea Green Publishing)

HOWARD: All of the solitary bees that that live in readymade cavities, and they could be cavities in a wall or they could be manmade nesting tubes made out of cardboard tubes or bamboo or something like that. The thing about these cavity nesting solitary bees, all of the mason bees and all of the leaf cutters as well, is that they are opportunists. So they take advantage of existing empty cavities. And the mason bees the way that their life cycle goes is so simple, really, they...I'm watching them out in our front garden at the moment. Once they've mated, the males have absolutely nothing to do then with the rearing of the brood. And then each individual female sets about searching for a place to lay her eggs in. And she's probably got about, say 20 or 30 eggs to lay in her short life on the wing. And so suppose you've got a bee hotel, bee nesting box in your back garden, and she chooses one of your bamboo tubes. First thing she'll do is she blocks off the back with a little bit of mud, which she's mined. That's why she's called a mason bee. And then she goes backwards and forwards, backwards and forwards collecting pollen. This bee incidentally, doesn't collect her pollen in pollen baskets, like the social bees. The bumblebees and honeybees have great big baskets to collect pollen. She collects them underneath her abdomen on little stiff, branched hairs. So she takes all of this pollen back in and she drops it in the back of the nesting tube. And when she's collected sufficient of this pollen, she taps it all into place. And then she lays an egg on top of the pollen. When she's laid that egg, she then collects more mud and she blocks that little cell off. And then more pollen, another egg and another bit of mud. And she'll go all the way to the entrance of the tube. And when she gets to the very edge of the tube, she blocks it off with a big plug of mud to seal the tube so that the whole tube is sealed. And the other thing she does, which is incredibly clever, is she lays female eggs at back and male eggs at the front. And this is because these often are predated, these nests, by birds. And it is better for the species that it's the males that are predated than the females. So they're all, they're all so, so different. Once you make the time to sit and watch them, if you have the time which of course we do have at the moment, it's just lovely to watch them and mind boggling to think what they get up to.

Two red mason bees work to seal up their nests. (Photo: Nigel Jones, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, we've heard that insects have all kinds of are in really sharp decline in populations, including bees. How bad is the population collapse for bees specifically? And why is that?

HOWARD: So, some of the most endangered, the rarest bees, it's become very clear that it's habitat loss that is the prime, the main driver. Pesticides, and by pesticides, I mean, insecticides, herbicides, fungicides, molluscicides, you know, the whole gamut of "-cides". Climate change is massive. And, you know, 10 years ago, I hadn't quite realized how big an issue climate change was. There's pathogens, and parasites, diseases, invasive species, poor husbandry, so you know, the way that we look after them or don't look after them is also a contributing factor.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I mean, there's a lot there that you just said. I mean, with climate change alone, I would imagine you know, some plants are flowering earlier than they used to. And the bees, maybe they don't coincide with that and they miss their meal and can't lay their eggs and that's that or maybe it's too hot for them, too cold for them. I mean, it's so very complicated.

One of the consequences of climate change is altered flowering times for certain plants, leading to a mismatch in timing with insects coming out of hibernation. (Photo: m.shattock, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

HOWARD: It is everything you just said. What's obvious to us is if it's flooding. If it's flooding, then bumblebee nests are going to flood. And if there's a drought, the plants are going to wither and die, or the nectar is gonna dry up and there's not going to be enough for the bees to feed. If the weather is terrible, they're not gonna come out. So those are the obvious effects of climate change. But you also mentioned plants flowering at different times, to the pollinating insects, that that pollinate them. And that's happening a lot. And one of the reasons that that is happening, I only really am able to tell you about Europe and the United Kingdom. So, as the weather gets warmer in the south of England, we start to have lots of our insects coming out of hibernation a lot earlier than they used to. So in February, instead of April. But plants tend, as well as taking their cue from the warmth and the weather, they also take their cue from daylight hours. So, whilst the weather is now warmer in February than it used to be, the daylight hours are no longer than they used to be. So that means, you know, it's it's very often it's the insects emerging before the flowers.

BASCOMB: Well, what can the average person do to help bees and other pollinators for that matter?

HOWARD: We can do so much and this is the beauty of trying to help bees. It's not like trying to to save, you know, one of our our huge, great, big, wonderful carnivores, everybody can do something to help bees. So for starters, if you have access to growing space, you know a back garden, a backyard, or a larger piece of land, then we can grow a larger variety of plants that are rich in pollen and nectar than we already do. So whatever you do, you know, plant more. And with these 20,000, 25,000 different species of bee, clearly it's not a case of one plant suits all bees, or one bee pollinates all plants. So we need to increase diversity. We need flowers of different sizes as well. Flowers for a long-tongued bees and short-tongued bees. Flowers with flatheads, flowers with bells, tubes, cups, huge, huge variety of flower shapes. So that's important. Stop using pesticides, find alternatives. And once you stop using the insecticide, you know, a whole host of beneficial insects move in and they take care of the pests for you so that's another thing. And the other thing I always think is one of the most beautiful things we can do, and maybe this is where I would start, is get out in your backyard, or your garden, or your plot and look. And notice, and watch, and observe, and get to know the insects that you already have there. It'll be really obvious to you if you have a plant that nobody visits, you know, if there's no interest in one plant, but another is just covered in insects throughout the day, then maybe plant more of the one that's covered in insects. And I also think if you start to take time to watch, it's very difficult not to start falling in love with them. And then when that happens, you start to look more deeply into causes of their decline. And you tend to want to do more to help them anyway then. So I think that's important. And providing habitat, allowing some of your growing space to be messier. You know, be a lazy gardener and allow some of your plot to re-wild.

Many think that beekeeping is the best way to save bees, but this simply puts a hive of honeybees, who are not considered endangered, into one’s care. Instead, Brigit recommends planting a variety of flowers and moving away from insecticides as the best steps to protect these pollinators. (Photo: Franz Jachim, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: You know, I have to tell you, since I've been reading your book, I notice bees more. You know, I think I feel curious. You know, what is this bee and what's it doing, what's it's activities? Is it making a nest in the leaves or is it just poking around in there? You know, it's so fascinating once you start to look how much more you see. And then you realize how little you really know.

HOWARD: Oh, I know. That's music to my ears. Do you know what, when I stopped relying on learning about bees from books, and started just watching them myself, and imagined what's it doing under that pile of leaves. And if it's a huge bumblebee, and you keep watching, and it gets up and it flies away, and it doesn't come back, you think, oh, well, it was just investigating. But if you sit long enough, and it comes back, then you think oh my gosh, it could be nesting there. And you only notice it if you give it the time of day, if you sit and really, really watch. I start to recognize the different sounds as well, that different bees make, you know, the huge great big bumblebees, the bigger they are, the deeper their buzzing. [LOW PITCHED BUZZ] And then sometimes you just get used to that noise and you hear [MEDIUM PITCHED BUZZ]. And you think, oh, that's not a bumblebee and you then go searching for that bee. And one of the most exciting connections I made of all was hearing another buzz, a very, very weird buzz. And it was kind of like a dentist drilling. I was sitting in my garden listening to bees and I heard [THREE HIGH PITCHED BUZZES] and I thought, oh, that sounds like a bee that's maybe stuck in a spider's web or something. It sounds really alarmed. And I followed the sound of the buzz, and I found this bee inside a poppy and she was going round and round and round inside the poppy, having a pollen bath. And so I listened and watched and in time I realized that the bees, when they came to the poppies always made that noise. When I looked it up to see, you know, what's going on here. It turned out that those bees were buzz foraging or sonicating. And it's really only bumblebees, and some of the solitary bees that can do this. Bumblebees, what they do is they come and they wrap themselves around the flower, and then they disconnect the flight muscles inside their thorax, but they continue to vibrate. So they're vibrating the indirect flight muscles twice as fast as they would if they were flying. It's called sonication and it causes the plant to literally explode out its pollen. And this is what the bees were doing on the poppies. Listen for it, next time you have time to sit in your garden if you hear what you think might be a very distressed bee, have a look and it could be a bee buzz pollinating. So yeah, that's again, it's to do with noticing, and watching and enjoying, and learning from the bees actually, learning from the bees themselves rather than the books.

A halictid bee uses “buzz pollination”, or sonication, to dislodge the pollen from the flower. (Photo: Bob Peterson, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: You've obviously written just such a delightful book here. I've really enjoyed reading it and you set out on this quest to learn about nature, to reconnect with nature, and used bees as a vehicle for that. How safe is it to say that you've been pretty successful here?

HOWARD: I'm back way beyond anything I have ever experienced, even as a child, I think. I have the awe and wonder that had been lost. I tread more carefully everywhere I go. I mean, when I was a child, I was like a bull in a china shop. I'm a lot more careful now. I'm a lot more respectful. I'm more grateful. And I give back now, you know, as children, you're not in a position, maybe to give back. So my relationship I think has become more reciprocal now. I think that's the biggest thing. I'm so grateful to the bees for providing whatever this is, a window, or a door back to nature. I'd love to go backwards. I'd love for this to have happened earlier, or for me never to have lost my connection. My hope is for my grandchildren and for other children that they don't lose it like so many of us. And I hope my book inspires people to go out and look in their gardens. Just that. If it does, then that's my job done.

Brigit Strawbridge Howard is a bee advocate, wildlife gardener, naturalist, and author of the book Dancing with Bees: A Journey Back to Nature. (Photo: Courtesy of Chelsea Green Publishing)

BASCOMB: Brigit Strawbridge Howard is a bee advocate and author of the book Dancing With Bees: A Journey Back to Nature. Brigit, thank you so much for this delightful conversation.

HOWARD: No, thank you. It's my pleasure. Thank you, Bobby.

Related links:

- Find out more about Dancing with Bees: A Journey Back to Nature on the Chelsea Green website

- Brigit Strawbridge Howard’s blog, Bee Strawbridge

- Brigit Strawbridge Howard on Twitter

[MUSIC: Wynton Marsalis with Eastman Wind Ensemble, “The Flight of the Bumblebee from Tsar Saltan” on Carnaval, CBS Masterworks]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Anne Flaherty, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Kori Suzuki, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth.

we tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio.

Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Anne Flaherty, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Kori Suzuki, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth.

we tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio.

Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth