Tracking Migratory Species from Space

Air Date: Week of July 17, 2020

Russian cosmonaut Sergey Prokopyev lays cable for the installation of the ICARUS animal-tracking experiment, August 15, 2018. The system is being tested in the summer of 2020. (Photo: NASA Johnson, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The field of wildlife tracking is getting a major upgrade thanks to a new initiative called ICARUS, which uses special equipment on the International Space Station to allow researchers to track much smaller species than ever before, including tiny migrating birds and even insects. Autumn-Lynn Harrison, Program Manager of the Migratory Connectivity Project at Smithsonian Institution, joins Bobby Bascomb to discuss how the new technology works and will aid conservation efforts.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

Information collected from orbiting satellites can tell us a lot about the weather, our changing climate, and the abundant life on earth. And thanks to advances in technology, soon we may be able to watch, in real-time, the movements and migration of tiny winged species, including insects. The project is called ICARUS and the International Space Station is now home to the first module that can receive signals from new micro transmitters strapped on tiny animals. Autumn-Lynn Harrison is Program Manager of the Migratory Connectivity Project at Smithsonian Institution. Autumn-Lynn, welcome to Living on Earth!

HARRISON: Thank you so much, Bobby.

A long-tailed jaeger after release. (Photo: Neil Paprocki)

BASCOMB: So what kind of data are you hoping to collect?

HARRISON: The ICARUS tags will include a number of different sensors that collect GPS data; and accelerometry, so you'll be able to see how an animal is moving in three dimensions through the accelerometry sensors; and temperature is a fairly standard sensor on a number of existing satellite tags as well.

BASCOMB: And I understand that you've brought along a tracker that you use to study migrating birds. Can you describe how it works?

HARRISON: Sure, it's my pleasure. This is a tracking device that I have used on shorebirds and on seabirds. It weighs about the same weight as an American nickel. It is about the size of the tip of my thumb, and it has a small solar panel on the top and a very long antenna to communicate with satellites.

Black-bellied plover with satellite tag on its back and antenna extending out beyond tail. (Photo: Ryan Askren, USGS)

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. It's, it sort of looks like a really teeny tiny dog harness around it, that you would strap onto the animal, I think.

HARRISON: Yes. So attached to the tag is a little bit of Teflon ribbon. So this is made out of the same material that lines cooking pans. It's very strong, and it's formed into a harness that's sort of like a little climbing harness. In this case, this tag would go over the legs of the bird and sit on the bird's lower back, so it wouldn't in any way get in the way of flight because it's not held on the back or around the wings.

BASCOMB: And what makes the ICARUS project such a large step forward from previous technology for animal tracking, like the one that you are using now?

HARRISON: Sure, there are a number of really good reasons why those of us who study animal migration are very excited about the ICARUS initiative. The tags will provide GPS data. The tag that I use now also communicates with satellites, but it uses a lower accuracy way of estimating the animal's position on Earth. So with the ICARUS tags, we will be able to get within 10 meters to 30 meters accuracy on where the animal is. The tags that I use now can range between 100 meters and 2500 meters, so two and a half kilometers accuracy. So the ICARUS tags will be much more accurate in about the same small package. They are also intended to be a lot less expensive. The tag I use costs about $3800 for one tag, and the ICARUS tags are estimated to be $500.

A satellite tag, complete with harness and long antennae, and a tiny light-level geolocator for scale with an American nickel. (Photo: Autumn-Lynn Harrison)

BASCOMB: Well, can you give us some examples of animals that scientists will be able to track using this technology that maybe were more difficult before, and what you hope to learn that you didn't know?

HARRISON: Yes, one of the advantages of the ICARUS system is that the tags are already quite small and will only get smaller. So when they are about the size of one gram, the size of maybe a pill of aspirin, this will enable us to track small songbirds, large insects. We've never been able to track these types of small animals with GPS accuracy, in real time. For these smallest birds, the mysteries to uncover really infinite. And ICARUS is going to help us do that.

BASCOMB: Do you have a favorite migrating animal that you study?

HARRISON: Well, I have lots. I love animal migration. I primarily work on shorebirds and seabirds and mostly in the Arctic region. So I've studied shorebirds that look as dapper as James Bond and wear a nice black and white tuxedo, and really acrobatic, predatory seabirds. But the one that has stuck with me is not just the bird that has the longest migration, but the animal that has the longest migration of any animal that we know of in the world, is the Arctic tern. This bird flies from the high Arctic, all the way to Antarctica, so from pole to pole. And the first time I held one of these birds in my hands, I was about to attach a tiny little tracking device. And I mean, you just get so warm in your heart to think that this is the bird that has the longest migration and makes such an heroic, athletic journey every year, to and from the poles. It's -- nothing better than that.

Autumn-Lynn Harrison with an Arctic tern. (Photo: Courtesy of Autumn-Lynn Harrison)

BASCOMB: It's so, so impressive! And they're small, right? I mean, they weigh a few ounces, is that right?

HARRISON: Arctic terns are very small, less than 100 grams, and so they wouldn't be able to carry large satellite tags. So the tag that I use is called a light level geolocator. It's about the size of a little medicine pill, and this attaches to a leg band on the leg of the tern. So this senses light level and has a little internal clock that can help us estimate the bird's position on the Earth. That tag might only get us within one to three degrees of latitude and longitude, and the period of the equinox is very unreliable for those types of tags that use light level to estimate position on Earth. So there's a lot of limitations with existing technology. With a one gram ICARUS tag, we would get within 10 to 30 meters of where that Arctic tern is. And we would be able to collect positions hourly, for example. Now, we typically have daily positions with our light level geolocators.

BASCOMB: Wow. And they go pole to pole; but from what I understand the ICARUS technology won't actually work at the poles themselves, is that right? What are the limitations to the technology?

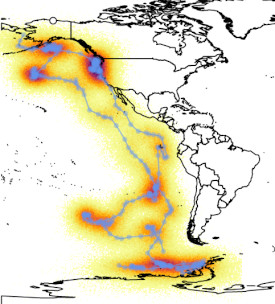

The migration path of an Arctic tern caught and tagged by Autumn-Lynn Harrison. Red indicates the best estimate for a given location along the bird’s path, since the light-level geolocator tag the tern was carrying only provides a rough estimate of its location. (Image: Joanna Wong)

HARRISON: Yes, that is one of the major limitations of ICARUS currently. And it's one of the limitations for my field of study, because I do work in the Arctic. And so with all of the advantages of ICARUS being able to track animals in real time, that won't yet be possible in the Arctic, which is one of the most rapidly changing places on the planet, that we would like to be able to understand real time responses to major heat waves, like what is happening right now in Siberia. I'm actually tracking a seabird that was just in the hottest region of Siberia, and this week left for Canada. So that real time information is available with our current technology, but in the Arctic region about north of 60 degrees, I think, latitude, we won't be able to get that real time data yet. But if you're studying a migratory animal that leaves the Arctic then the data will upload after the tag and the animal have both left the Arctic. The hope is that more ICARUS modules will be deployed on other satellites in the future to help cover the polar orbits and allow us to get some of the same benefits from ICARUS for Arctic and Antarctic species.

BASCOMB: Now, why is advanced animal tracking important for animal conservation as a whole, would you say?

Downloading data from a tiny light-level geolocator looks a bit like jumpstarting your car. (Photo: Autumn-Lynn Harrison)

HARRISON: We have long wanted to protect animals throughout their ranges. So I study migratory species; these are animals that may travel through 30 different countries in the course of a year. And when they start declining, we need to know where they go and when they go there so that we can leverage all of the resources of every country that might be able to benefit that species. Every country has different laws, different conservation initiatives. And so understanding when and where declining migratory species are, this is the only way that we know whether we have spent money on the right interventions at the right time in the right place.

BASCOMB: And I would think, I mean, it's dynamic, right? With climate change, animals are probably choosing different places to migrate to and from, and what was reasonable to protect a decade ago may not be the same place that they're choosing today?

An Arctic tern flies away after being banded with a light-level geolocator, seen on its leg. (Photo: Arliss Winship)

HARRISON: Yes, it's a good point that ranges are shifting. We're already seeing examples of animals moving into places that we didn't previously have records. One of the things that I think about a lot with studying Arctic species is that some of the data that I'm collecting are the very first migratory pathways of these species. So the very first time we have known where and when these species are. And so our baseline information is actually being collected only now, which means that we may not even know how things have changed over the past 10 years, which was an area of rapid change in the Arctic.

BASCOMB: Right. Now, I've read that scientists are actually working on a smartphone app to go along with the ICARUS technology so people can track their own favorite animals at home. Can you tell me some more about that?

Autumn-Lynn Harrison with a long-tailed jaeger. (Photo: Courtesy of Autumn-Lynn Harrison)

HARRISON: Sure, there's an existing smartphone app that already allows this to happen that's linked with the Movebank animal tracking database. And the idea is that you can pull up an app on your phone, and you can see available animals that are being tracked, of many different species, and follow them along day after day, and see their migrations in almost real time. So it's a way for the public to be able to directly engage with these amazing journeys of animals.

BASCOMB: I love the idea of somebody whipping out their smartphone and looking at the bird, let's say, that was in their backyard and following it to Chile; or somebody in Argentina, following it to you know, wherever it's going in North America, if that's the case. It seems like a really great way to sort of bring people together as well.

HARRISON: Absolutely. I like to think of migratory birds as pen pals that we exchange across international borders, and we send them to you one season and then you send them back to us. And they are a shared heritage of many different communities and countries. And I think being able to visualize that in real time will just drive that inspiration and passion even more to conserve migratory animals.

Harrison and colleague Lee Tibbitts attaching a satellite tag to a black-bellied plover. (Photo: Elyse Gottesman)

BASCOMB: Autumn-Lynn Harrison is program manager of the Migratory Connectivity Project at the Smithsonian Institution. Autumn-Lynn, thank you so much for your time today.

HARRISON: Thank you so much, Bobby. It's a pleasure.

Links

About the Migratory Connectivity Project at the Smithsonian Institution

NYTimes | “With an Internet of Animals, Scientists Aim to Track and Save Wildlife”

Download the Animal Tracker app on Google Play to follow your favorite animals

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth