July 17, 2020

Air Date: July 17, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate Disinformation on Facebook

View the page for this story

The Natural Resources Defense Council, Earthjustice and 350.org are joining more than 1000 companies in pausing their advertising on Facebook in July as part of the “Stop Hate for Profit” campaign. Climate journalist Emily Atkin, who writes the newsletter HEATED, joins Steve Curwood to discuss why these groups are taking a stand against the spread of racism, white supremacy and climate disinformation on this giant social media platform. (09:21)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News editor Peter Dykstra and Bobby Bascomb go Beyond the Headlines to talk about how resource extraction is impacting Indigenous communities from the Amazon rainforest to the Sámi in Finland. And in the history calendar, Peter and Bobby remember two Brazilian environmental activists who were murdered in retaliation for their efforts to protect the Amazon rainforest. (03:53)

Tracking Migratory Species from Space

View the page for this story

The field of wildlife tracking is getting a major upgrade thanks to a new initiative called ICARUS, which uses special equipment on the International Space Station to allow researchers to track much smaller species than ever before, including tiny migrating birds and even insects. Autumn-Lynn Harrison, Program Manager of the Migratory Connectivity Project at Smithsonian Institution, joins Bobby Bascomb to discuss how the new technology works and will aid conservation efforts. (11:05)

Clean Energy in Space to Save Planet Earth

View the page for this story

With an historic SpaceX launch and several Mars missions underway, 2020 is proving a pivotal year for space exploration. Steve Curwood speaks with Greg Autry, Director of the Southern California Commercial Space Initiative at the University of Southern California, about how innovations in space technology such as solar charging stations that beam energy back down to Earth, and mining hard rock materials in space, could displace earth-bound activities that are hard on the environment. (06:38)

The Sirens of Mars

View the page for this story

The search for life elsewhere in the Universe is focused now on Mars, our closest planetary neighbor, with the Perseverance mission planned to launch sometime between the end of July and the middle of August. Astrobiologist Sarah Stewart Johnson is a Georgetown associate professor and NASA scientist who has spent her career searching for answers to these questions. Her book Sirens of Mars: Searching for Life on Another World captures the intersection between planetary science and her life's journey, and she joins Host Steve Curwood to explore the big questions that define space exploration and the human species’ fascination with Mars. (16:16)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Emily Atkin, Greg Autry, Autumn-Lynn Harrison, Sarah Stewart Johnson

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

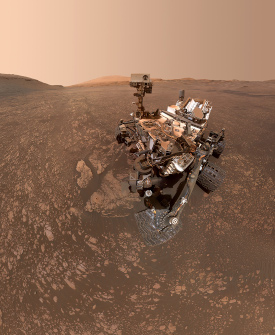

The Curiosity rover mission to Mars has provided scientists hope that we may yet find life on the red planet.

JOHNSON: Curiosity has revealed that this is a habitable environment, you know, we've moved beyond 'follow the water' to understanding that all the ingredients necessary for life as we know it are there, or were there, in the surface of Mars.

BASCOMB: Also, a look at the potential for a solar panel station in space to provide clean energy here on earth.

AUTRY: So, you can put the station in space better energy production, 7 to 8 times better no night time no clouds, beam it down to a point on earth and use it to drive what ever it is you need to do on earth. So, that's the vision and the promise.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Climate Disinformation on Facebook

Facebook has come under scrutiny for its policies on notifying users about climate disinformation articles published as opinion pieces. (Photo: Book Catalog, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The Natural Resources Defense Council, Earthjustice and 350 dot org are joining more than 1000 companies in pausing their advertising on Facebook this month as part of the “Stop Hate for Profit” campaign. These three major environmental groups are demanding that Facebook take steps to curb the spread of racism, extremism and misinformation about climate change on its platform. Most other environmental groups, though, have yet to take a stand on Facebook policies on hate and climate denialism. Emily Atkin is a climate journalist and author of the climate crisis newsletter “Heated,” and she joins me now to discuss this divide. Welcome to Living on Earth.

ATKIN: Thank you for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: So Emily, how did all this come about?

ATKIN: This came about one day when a reporter that I work with very frequently named Judd Legum came to me and pointed out a story that had just been published in E&E News, which is sort of like an industry publication. And the story was about this group called the CO2 Coalition. And it's this group in Washington, powerful, fossil fuel-funded group that argues that carbon dioxide is good for you, you know, we need more of it to breathe and the more we pollute, the healthier we are that kind of stuff. So they had published this op-ed in the Washington Examiner claiming that all climate models are wrong. And climate science is basically BS. They posted it on Facebook and Facebook's independent fact checking process kicked in. And fact checkers publishing scientists deemed the article false because it was obviously false. The CO2 Coalition went back to Facebook and said, "Hey, this is an opinion article. So there shouldn't be a false label on it." And Facebook said, "You're right and took it off." Because apparently Facebook has a policy saying that if you have an opinion piece, if it's an opinion piece, then it's not subject to fact checking rules. And Judd pointed out this article to me and said, "Is this important, do you think?" And I said, "Yeah, I think this is really important." And so we started our reporting from there.

CURWOOD: This is really risky for science, isn't it? I mean, right now we're going through this pandemic, where people are pointing to scientists are saying, well, that that's their opinion, and not really paying attention to the hard science behind what's going on.

In 2017, researchers observed a giant iceberg the size of Delaware that had recently calved off of the Larsen C ice shelf. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, CC BY 2.0)

ATKIN: I think it goes beyond being risky for science. I think it's risky for public health. We know the consequences of spreading misinformation about epidemiology and about the way coronavirus spreads. It's the same when we're talking about climate change, which is also a public health threat. If we're allowing misinformation to be spread about climate change, we're threatening literally millions of people's health. And it's something that Facebook has so far refused to really grapple with.

CURWOOD: I mean, Facebook says, Look they shouldn't moderate their content, it's not a media company, but it's a public forum for free speech. What does that meant for climate deniers, do you think?

ATKIN: What I thought was the most compelling and important part of this whole story was that the CO2 Coalition? You know, fossil fuel industry-funded climate denial group said that they were really thankful for Facebook's opinion content loophole, because now they could use it to spread their climate denial, because before they weren't getting traction with mainstream media anymore, you know, reporters from the New York Times and The Washington Post aren't reaching out to them for the other side of the climate story now. And finally, you know, they found what they believe is an ally in Facebook. So if that's what Facebook wants to be, then that's what we need to think of it as.

CURWOOD: Now, at the same time, Facebook has been, quote, fact-checking climate scientists like Katharine Hayhoe down there in Texas, right. As I understand it, they blocked Katharine Hayhoe’s videos related to climate research because they said they were political and she had to give certain information to register them. In other words, how fair is it to say that Facebook’s perspective in this case seems to be that well, science is political?

ATKIN: It's kind of backwards, right? On one hand, they're saying well, this scientific content his opinion, so it doesn't need extra fact checking or extra certification information. And then they say on the other hand, well, this climate information is political. And so we need all of this other certification information. And it's a basic misunderstanding on Facebook's part on what science is. It's neither opinion nor political. It's the best process that we have to determine objective truths. And I don't think it's controversial to say that that should be something that our biggest social network, our biggest purveyor of information, should understand in its policies. And right now it doesn't appear to.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has argued in the past that Facebook is not a media company, and therefore should not regulate content posted on the platform. (Photo: Billionaires Success, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now as many advertisers are boycotting Facebook to try to compel them to take a stronger stance on racism and hate speech. Some environmental groups, I'm thinking of Earthjustice and 350.org have joined that campaign and added their demands that Facebook take steps to limit climate denialism as well, but other environmental activists such as Sierra Club USA have not joined in. Talk to me about that divide, please.

ATKIN: It's a really interesting question that these environmental groups have to deal with, which is how do they want to spend their money? Do they want to spend it on a platform that actively is spreading climate change disinformation but at the same time really helps them get their message out? I think it's really hard for a lot of nonprofits and charities and advocacy groups to balance those concerns. I think it's important to note that the ongoing Stop Hate for Profit campaign specifically says they're only asking companies, businesses, corporations to boycott Facebook for the month of July. They're not asking nonprofits or advocacy groups to do it because they know that's a really tough choice--to ask them to stop spreading a message of social justice, climate justice, right. At the same time, the Stop Hate for Profit campaign welcomes nonprofits and advocacy groups to join if they would like to, there's a faction of environmental groups that say we should be putting our money where our mouth is and this is not where movements are built movements are not built on Facebook. You know, they're built in the real world. But there are others that say Facebook is the is the best place that we operate right now, especially during a time of coronavirus.

CURWOOD: Facebook has actually agreed to take some action against hate speech and violent language. That's correct, yeah?

ATKIN: Yeah, Facebook has taken a number of actions against hate speech and violent groups and also against coronavirus disinformation. And I think that that's why climate advocates and people who understand climate science see sort of an unequal treatment here. Facebook doesn't seem to recognize that when you spread misinformation about climate change, it's the same detrimental effect as spreading misinformation about a health threat or racism honestly, because climate change affects black and brown communities and minority communities in such a more catastrophic scale than affluent white people. I can't really stress this enough. If we don't act on climate change--this isn't my opinion, this is the science--people will die. A lot of people will die and mostly black and brown people will die. And when we're allowing this information to be spread about that we're allowing that to happen.

Protests in downtown Calgary focus on the impact of individual investments in the five major Canadian banks on climate change. (Photo: Visible Hand, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Emily, before you go, to what extent do you think people who are concerned about the climate might start to boycott companies that advertise on Facebook? Some companies have stepped back from Facebook over the racism and violence--maybe companies might take a second look, if their consumers and their brands start to get battered by public concern?

ATKIN: You know, climate activists have organized successful boycotts of banks that fund Arctic drilling, right, they successfully pressured the financers of the climate crisis to stop financing really dirty projects, right. And it's becoming a trend in environmental and climate activism to start targeting, not the fossil fuel companies, not the problem itself, but the companies that fund the problem if that makes sense.

CURWOOD: Well, you know, famously a number of years ago, President George W. Bush said that we are addicted to oil. So it sounds like the boycotts aren't really focused so much at the addicts as the enablers.

ATKIN: Exactly. They recognize that oil companies don't have an incentive to change unless their wallet is threatened. Right. That's why this Facebook ad boycott has made such a stir. You yelling at Facebook online doesn't really matter to Facebook. But you taking away Facebook's money matters.

CURWOOD: Emily Atkin is a climate journalist and author of the climate crisis newsletter "Heated." Thanks so much for taking this time with us today, Emily.

ATKIN: Thanks for inviting me.

After the program was recorded, Facebook provided the following statement:

"When someone posts content based on false facts on our platform, even if it's an op-ed or an editorial, it's still eligible for fact-checking. We're working to make this clearer in our guidelines so that fact-checkers can use their judgement to better determine whether something is an attempt to mask false information under the guise of opinion or actually opinion content."

Related links:

- Emily Atkin | “Heated Newsletter”

- The New York Times | “How Facebook Handles Climate Disinformation”

- Vox | “Elizabeth Warren Wants Answers on Facebook’s Fact-Checking Loophole”

[MUSIC: The Wayfaring Strangers, “Shifting Sands of Time” on Shifting Sands of Time, by Mark Simos-Lisa Aschmann, Rounder Records]

Beyond the Headlines

The Amazon rainforest has long been endangered by logging and extraction, but now the Indigenous people who live there are being exposed to coronavirus as well. (Photo: Neil Palmer, CIAT, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: It's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News that's EHN.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby. There's great concern that as loggers make inroads into the Amazon as it's converted into ranches and farms, and even as religious missionaries make their way deeper and deeper into the Amazon, that one of the things that's going to hit you right along is COVID-19. And these tribes have little defense against the incursion, let alone little defense against the disease. And it could be that President Bolsanaro, has looked for any opportunity to make further inroads into the Amazon, even at the expense of its native inhabitants.

BASCOMB: I imagine that's very, very frustrating for the environmental groups that work with the native people there. I mean, Brazil has a wonderful constitution that really strongly protects their rights to the land and their rights to live their life as they want, but that's not being respected these days.

DYKSTRA: You and your constitution, Bobby. You know, it's so within authoritarian government and the threats on a number of different fronts, including disease are making a bad situation even worse for the Indigenous residents of the Amazon.

BASCOMB: Mmm Indeed. Well, what else do you have for us this week?

Sámi Natives observing drilling rigs taking core samples of precious metals. The Sámi people live in Finland’s northwestern Plains and have herded reindeer since ancient times. (Photo: Courtesy of Thomas Nielsen)

DYKSTRA: In a very different part of the world there's an Indigenous population in Europe in Northern Finland also in Sweden and Norway. The Sami people are as dependent on herding reindeer as the Plains Indians were in North America on the bison. They're the center of their culture, their food and reindeer herding for the Sami is under threat because their land includes precious metals needed for get this electric vehicle batteries.

BASCOMB: Oh, the irony. What are they finding there that's so attractive?

DYKSTRA: Metals like nickel, copper, vanadium, cobalt, all used in large supply in car batteries, particularly the larger ones that are going to be needed to drive EVs are found there. Europe wants its own supply of these metals. Finland wants to ride this potential economic wave to become the equivalent of an oil state only in precious metals. The Sami people have very, very little recourse to protect their land and culture.

The livelihood of the Sámi people will likely be threatened by mining extraction of minerals for electric vehicles. Currently there is little protection for the Sámi people, but if Finland ratifies the ILO Convention on the Rights of Indigenous People, they might have more control over their traditional homeland. (Photo: Courtesy of Thomas Nielsen)

BASCOMB: You compare the reindeer to the bison of the North American plains and the native people here were also pushed off their land when something valuable was found beneath it, you know, be a gold oil, minerals. Seems, it seems like a familiar story.

DYKSTRA: It is although I would like to think that we would have progressed at least a little in the past 150 years.

BASCOMB: That would be nice.

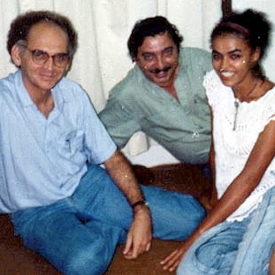

Brazilian environmental activist Chico Mendes (center), alongside Gregorío (left) and Marina Silva (right). (Photo: Marina Silva, Flickr, CC BY 2.O)

BASCOMB: Well, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: July 21, 1980 40 years ago. The head of the Brazilian rubber tappers union, Wilson Pinheiro was murdered in his home Pinheiro had become an adversary to the ranchers, loggers, farmers, who are making inroads in the Amazon. His murder proceeded that of Chico Mendez. Both of their lives particularly Mendez, were featured in a book called The Burning Season, a TV movie by the same name starring the late Raul Julia. And that book and movie the book by journalist, Andy Revkin helped for the first time show the plight of rubber tappers and native Amazonians up against the deforestation of the world's greatest forest.

BASCOMB: Well, thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News that's EHN.org and dailyclimate.org. And we'll talk to you again real soon.

Picture of the binational bridge between Brazil and Bolivia, dedicated to environmental activist Wilson Pinheiro. (Photo: Grullab, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 3.0)

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on these stories on the living on earth website. That's LOE dot ORG.

Related links:

- The Barents Observer | “Miners Hunting for Metals to Battery Cars Threaten Sami Reindeer Herders' Homeland”

- The National Observer | “Already Fighting for Their Lands and Lives, Indigenous Communities in Brazil Slammed by COVID-19”

- Learn More About Environmental Activists Wilson Pinheiro and Chico Mendes

[MUSIC: Rob Curto’s Forro For All, “Baiao” on Forro For All, by Luiz Gonzaga-Humberto Teixeira, Mezzogiorno Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Scientists are looking to space for better ways to study migratory animals right here on earth. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Rob Curto’s Forro For All, “Dois Nordestes-Roseira do Norte” on Forro For All, by Rob Curto and Pedro Sertanejo/Ze Gonzaga, Mezzogiorno Records]

Tracking Migratory Species from Space

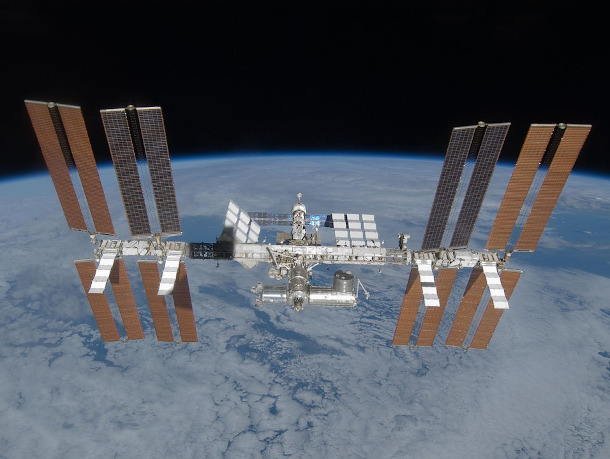

Russian cosmonaut Sergey Prokopyev lays cable for the installation of the ICARUS animal-tracking experiment, August 15, 2018. The system is being tested in the summer of 2020. (Photo: NASA Johnson, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

Information collected from orbiting satellites can tell us a lot about the weather, our changing climate, and the abundant life on earth. And thanks to advances in technology, soon we may be able to watch, in real-time, the movements and migration of tiny winged species, including insects. The project is called ICARUS and the International Space Station is now home to the first module that can receive signals from new micro transmitters strapped on tiny animals. Autumn-Lynn Harrison is Program Manager of the Migratory Connectivity Project at Smithsonian Institution. Autumn-Lynn, welcome to Living on Earth!

HARRISON: Thank you so much, Bobby.

A long-tailed jaeger after release. (Photo: Neil Paprocki)

BASCOMB: So what kind of data are you hoping to collect?

HARRISON: The ICARUS tags will include a number of different sensors that collect GPS data; and accelerometry, so you'll be able to see how an animal is moving in three dimensions through the accelerometry sensors; and temperature is a fairly standard sensor on a number of existing satellite tags as well.

BASCOMB: And I understand that you've brought along a tracker that you use to study migrating birds. Can you describe how it works?

HARRISON: Sure, it's my pleasure. This is a tracking device that I have used on shorebirds and on seabirds. It weighs about the same weight as an American nickel. It is about the size of the tip of my thumb, and it has a small solar panel on the top and a very long antenna to communicate with satellites.

Black-bellied plover with satellite tag on its back and antenna extending out beyond tail. (Photo: Ryan Askren, USGS)

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. It's, it sort of looks like a really teeny tiny dog harness around it, that you would strap onto the animal, I think.

HARRISON: Yes. So attached to the tag is a little bit of Teflon ribbon. So this is made out of the same material that lines cooking pans. It's very strong, and it's formed into a harness that's sort of like a little climbing harness. In this case, this tag would go over the legs of the bird and sit on the bird's lower back, so it wouldn't in any way get in the way of flight because it's not held on the back or around the wings.

BASCOMB: And what makes the ICARUS project such a large step forward from previous technology for animal tracking, like the one that you are using now?

HARRISON: Sure, there are a number of really good reasons why those of us who study animal migration are very excited about the ICARUS initiative. The tags will provide GPS data. The tag that I use now also communicates with satellites, but it uses a lower accuracy way of estimating the animal's position on Earth. So with the ICARUS tags, we will be able to get within 10 meters to 30 meters accuracy on where the animal is. The tags that I use now can range between 100 meters and 2500 meters, so two and a half kilometers accuracy. So the ICARUS tags will be much more accurate in about the same small package. They are also intended to be a lot less expensive. The tag I use costs about $3800 for one tag, and the ICARUS tags are estimated to be $500.

A satellite tag, complete with harness and long antennae, and a tiny light-level geolocator for scale with an American nickel. (Photo: Autumn-Lynn Harrison)

BASCOMB: Well, can you give us some examples of animals that scientists will be able to track using this technology that maybe were more difficult before, and what you hope to learn that you didn't know?

HARRISON: Yes, one of the advantages of the ICARUS system is that the tags are already quite small and will only get smaller. So when they are about the size of one gram, the size of maybe a pill of aspirin, this will enable us to track small songbirds, large insects. We've never been able to track these types of small animals with GPS accuracy, in real time. For these smallest birds, the mysteries to uncover really infinite. And ICARUS is going to help us do that.

BASCOMB: Do you have a favorite migrating animal that you study?

HARRISON: Well, I have lots. I love animal migration. I primarily work on shorebirds and seabirds and mostly in the Arctic region. So I've studied shorebirds that look as dapper as James Bond and wear a nice black and white tuxedo, and really acrobatic, predatory seabirds. But the one that has stuck with me is not just the bird that has the longest migration, but the animal that has the longest migration of any animal that we know of in the world, is the Arctic tern. This bird flies from the high Arctic, all the way to Antarctica, so from pole to pole. And the first time I held one of these birds in my hands, I was about to attach a tiny little tracking device. And I mean, you just get so warm in your heart to think that this is the bird that has the longest migration and makes such an heroic, athletic journey every year, to and from the poles. It's -- nothing better than that.

Autumn-Lynn Harrison with an Arctic tern. (Photo: Courtesy of Autumn-Lynn Harrison)

BASCOMB: It's so, so impressive! And they're small, right? I mean, they weigh a few ounces, is that right?

HARRISON: Arctic terns are very small, less than 100 grams, and so they wouldn't be able to carry large satellite tags. So the tag that I use is called a light level geolocator. It's about the size of a little medicine pill, and this attaches to a leg band on the leg of the tern. So this senses light level and has a little internal clock that can help us estimate the bird's position on the Earth. That tag might only get us within one to three degrees of latitude and longitude, and the period of the equinox is very unreliable for those types of tags that use light level to estimate position on Earth. So there's a lot of limitations with existing technology. With a one gram ICARUS tag, we would get within 10 to 30 meters of where that Arctic tern is. And we would be able to collect positions hourly, for example. Now, we typically have daily positions with our light level geolocators.

BASCOMB: Wow. And they go pole to pole; but from what I understand the ICARUS technology won't actually work at the poles themselves, is that right? What are the limitations to the technology?

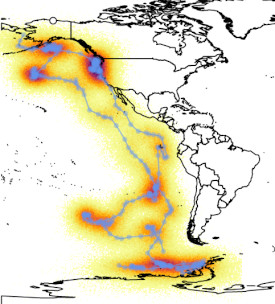

The migration path of an Arctic tern caught and tagged by Autumn-Lynn Harrison. Red indicates the best estimate for a given location along the bird’s path, since the light-level geolocator tag the tern was carrying only provides a rough estimate of its location. (Image: Joanna Wong)

HARRISON: Yes, that is one of the major limitations of ICARUS currently. And it's one of the limitations for my field of study, because I do work in the Arctic. And so with all of the advantages of ICARUS being able to track animals in real time, that won't yet be possible in the Arctic, which is one of the most rapidly changing places on the planet, that we would like to be able to understand real time responses to major heat waves, like what is happening right now in Siberia. I'm actually tracking a seabird that was just in the hottest region of Siberia, and this week left for Canada. So that real time information is available with our current technology, but in the Arctic region about north of 60 degrees, I think, latitude, we won't be able to get that real time data yet. But if you're studying a migratory animal that leaves the Arctic then the data will upload after the tag and the animal have both left the Arctic. The hope is that more ICARUS modules will be deployed on other satellites in the future to help cover the polar orbits and allow us to get some of the same benefits from ICARUS for Arctic and Antarctic species.

BASCOMB: Now, why is advanced animal tracking important for animal conservation as a whole, would you say?

Downloading data from a tiny light-level geolocator looks a bit like jumpstarting your car. (Photo: Autumn-Lynn Harrison)

HARRISON: We have long wanted to protect animals throughout their ranges. So I study migratory species; these are animals that may travel through 30 different countries in the course of a year. And when they start declining, we need to know where they go and when they go there so that we can leverage all of the resources of every country that might be able to benefit that species. Every country has different laws, different conservation initiatives. And so understanding when and where declining migratory species are, this is the only way that we know whether we have spent money on the right interventions at the right time in the right place.

BASCOMB: And I would think, I mean, it's dynamic, right? With climate change, animals are probably choosing different places to migrate to and from, and what was reasonable to protect a decade ago may not be the same place that they're choosing today?

An Arctic tern flies away after being banded with a light-level geolocator, seen on its leg. (Photo: Arliss Winship)

HARRISON: Yes, it's a good point that ranges are shifting. We're already seeing examples of animals moving into places that we didn't previously have records. One of the things that I think about a lot with studying Arctic species is that some of the data that I'm collecting are the very first migratory pathways of these species. So the very first time we have known where and when these species are. And so our baseline information is actually being collected only now, which means that we may not even know how things have changed over the past 10 years, which was an area of rapid change in the Arctic.

BASCOMB: Right. Now, I've read that scientists are actually working on a smartphone app to go along with the ICARUS technology so people can track their own favorite animals at home. Can you tell me some more about that?

Autumn-Lynn Harrison with a long-tailed jaeger. (Photo: Courtesy of Autumn-Lynn Harrison)

HARRISON: Sure, there's an existing smartphone app that already allows this to happen that's linked with the Movebank animal tracking database. And the idea is that you can pull up an app on your phone, and you can see available animals that are being tracked, of many different species, and follow them along day after day, and see their migrations in almost real time. So it's a way for the public to be able to directly engage with these amazing journeys of animals.

BASCOMB: I love the idea of somebody whipping out their smartphone and looking at the bird, let's say, that was in their backyard and following it to Chile; or somebody in Argentina, following it to you know, wherever it's going in North America, if that's the case. It seems like a really great way to sort of bring people together as well.

HARRISON: Absolutely. I like to think of migratory birds as pen pals that we exchange across international borders, and we send them to you one season and then you send them back to us. And they are a shared heritage of many different communities and countries. And I think being able to visualize that in real time will just drive that inspiration and passion even more to conserve migratory animals.

Harrison and colleague Lee Tibbitts attaching a satellite tag to a black-bellied plover. (Photo: Elyse Gottesman)

BASCOMB: Autumn-Lynn Harrison is program manager of the Migratory Connectivity Project at the Smithsonian Institution. Autumn-Lynn, thank you so much for your time today.

HARRISON: Thank you so much, Bobby. It's a pleasure.

Related links:

- More about ICARUS

- About the Migratory Connectivity Project at the Smithsonian Institution

- NYTimes | “With an Internet of Animals, Scientists Aim to Track and Save Wildlife”

- Download the Animal Tracker app on Google Play to follow your favorite animals

- Find the Animal Tracker app on the App Store

- More about Autumn-Lynn Harrison

[MUSIC: Nashville Mandolin Ensemble, “Where No Mandolin Has Gone Before (Theme from Star Trek)” on Plectrasonics, by Alexander Courage, Soundart Recordings]

BASCOMB: Coming up – The fascination with Mars and the chance that signs of life could be found there. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Nashville Mandolin Ensemble, “Where No Mandolin Has Gone Before (Theme from Star Trek)” on Plectrasonics, by Alexander Courage, Soundart Recordings]

Clean Energy in Space to Save Planet Earth

Solar panels in space, such as on the International Space Station, can generate more efficient energy than solar panels on Earth due to a lack of cloud cover, atmosphere, and nighttime. (Photo: WikiImages, Pixabay)

CURWOOD: Private business is moving deeper into space exploration and development, and just this year a rocket owned by the Space X company blasted off from Cape Canaveral, Florida and delivered two NASA astronauts to the international space station. They were the first to ride a commercial craft into orbit, and it was the first spaceflight launched from American soil in nearly a decade. There is much science to explore in space, but there are also business opportunities, as Greg Autry tells us. Greg directs the Southern California Commercial Spaceflight Initiative at the University of Southern California. He says solar energy farms orbiting the Earth could furnish vast amounts of renewable energy.

AUTRY: If you put these solar panels in space, like on the International Space Station, you can actually get much much more efficient solar energy generation because all of the solar radiation hits your panels. You don't have the atmosphere first of all filtering, you don't have clouds to worry about. And if you position the satellites, right, you can even eliminate nighttime as an issue, meaning they'll always be in the sun.

CURWOOD: Yeah, so you generate that power out there. How do you get it down to earth?

AUTRY: What you do is use an old technology that Nikola Tesla developed in the 19th century to transmit power between physical locations, wirelessly. And that was always his dream, something that he never perfected on a commercial basis but that has been tested many times since then. And you do this by converting the power into either a laser or microwave energy system and transmitting that to a rectifier that grabs the microwaves just like a radio antenna converts them back into electricity.

CURWOOD: Yeah, don't get in the way that beam though, huh?

Autry suggests mining for lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements on the moon. (Photo: Gregory Rivera, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

AUTRY: Yes and no. So there's been a lot of testing on how to transmit the power and the power density, meaning how tight the and the frequency that it's at, determine whether it's a problem for biological organisms. So molecules all have resonant frequencies. And that's why microwave ovens work at a particular about 2.5 gigahertz frequency that is the resonant frequency of water. So they're specifically designed to heat up water. But if you tune it out to a different frequency, your microwave oven wouldn't do anything the food. Pretty much, the beams would either be absorbed harmlessly or passed right through. So the science suggests that we can make this beam without a problem by making it both wide enough and choosing frequencies that aren't a problem. That said, for the first few tests, I imagine we're going to put them out in a desert location somewhere and suggest that airplanes don't fly through that and and that people don't go on the premises.

CURWOOD: So at what stage is this research and testing related to having solar stations in space, beam this down?

AUTRY: Yeah, well, certainly we have the solar generation capability. We're getting efficiencies in the high 20s out of our panels and the curve on that is getting better, the weight is getting better. We know how to beam the power. We've tested that several times. What we haven't done is done it in space to Earth. So there's a mission right now launched by the Department of Defense on their super secret X-37B spacecraft, which is kind of an unmanned space shuttle that they fly for long duration flights, sometimes more than a year and they launched one of the first in space demonstrations of space solar power. And so that's an exciting first step.

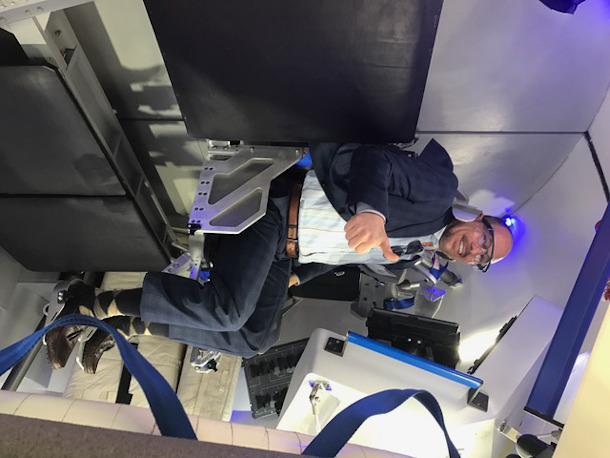

Greg Autry Inside the Boeing CST-100 Starliner capsule. He is director of the Southern California Commercial Spaceflight Initiative at the University of Southern California. (Photo: Courtesy of Greg Autry)

CURWOOD: Now, another opportunity that you've written about Greg is mining in space. what's being proposed for this? And how might that play into the conversation about dealing with climate disruption?

AUTRY: Right, so this plays in two ways. There's first of all, just the fact that obviously mining on Earth is is disruptive to the environment. Often what we do when we make mining, more highly regulated in the United States, it simply gets offshored to other places where it's done in, in methods that are often tragic, cobalt mining and Africa and lithium mining and South America, rare earth elements in China are done in ways that are highly disruptive. So what do you do about that? Well, those resources all exist, frankly, on the moon and in near Earth asteroids that are very accessible. And if you could move those extractive industries off of the earth, you can obviously take a big load off the disruption that we cause here. Additionally, if you want to build space solar panels, the best way to do it is to do it on the moon, and use resources from the moon and actually construct the final assemblies in space so that you're not lifting heavy loads off of the earth, which is expensive using our current chemical rocket technology. So that is the bigger vision, manufacturing and space to provide the energy needs that we need here on the Earth and to remove the load of extractive industries.

Greg Autry in the Vertical Assembly Building (VAB) at the Kennedy Space Center. (Photo: Courtesy of Greg Autry)

CURWOOD: What do critics of space mining say?

AUTRY: Well, there's a couple of different tags. There are people who believe it's not economically viable, and therefore you shouldn't try to do it. But I could give you a long list of historical things that weren't economically viable because there were no economic efficiencies of scale and the technology hadn't been developed and the entrepreneurial spirit that you see with SpaceX's launch hadn't been engaged on that problem. So I think that can be overcome. There are people who would like to leave the space environment alone, even though there's absolutely nothing living on the moon and nobody credible has any reason to believe that there would be, they don't want the moon as an object disturbed.

Greg Autry researches space entrepreneurship and commercial spaceflight. (Photo: Courtesy of Greg Autry)

Now, in my opinion, I come from the group of folks that think if you've got a dead rock full of resources, I would rather mine that than you know, tear up a rainforest in Brazil in order to leave the moon pristine. There's also an argument between communalism and private exploitation of space resources. Right? There are some people who believe that we should not allow commercial actors to go exploit resources anywhere in space. They should either either be left alone forever, or they should only be developed in some sort of communal United Nations-led organization. Those of us on the commercial space side believe that the incentive to commercial people and private investors to put money in, along with government leadership and regulation, will allow us to, to develop those resources for the benefit of all humankind. And then if we don't allow the private actors to profit, it will never happen.

CURWOOD: Greg Autry is director of the Southern California commercial spaceflight initiative at the University of Southern California. Greg, thanks so much for taking time with us today.

AUTRY: Thank you, Steve. I enjoyed it. Obviously, I could go on and I'd always love to talk to you again. Take care.

Related links:

- About Greg Autry

- Space Research Can Save the Planet – Again | Foreign Policy

[MUSIC: Nashville Mandolin Ensemble, “Where No Mandolin Has Gone Before (Theme from Star Trek)” on Plectrasonics, by Alexander Courage, Soundart Recordings]

BASCOMB: Coming up – The fascination with Mars and the chance that signs of life could be found there. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Nashville Mandolin Ensemble, “Where No Mandolin Has Gone Before (Theme from Star Trek)” on Plectrasonics, by Alexander Courage, Soundart Recordings]

The Sirens of Mars

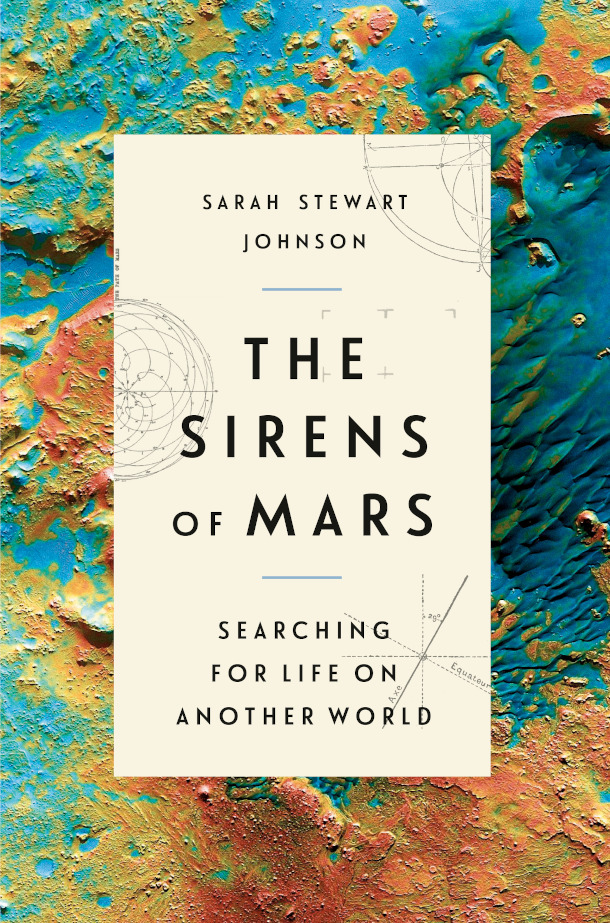

Sarah Stewart Johnson is the author of Sirens of Mars: Searching for Life on Another World. (Photo: Courtesy of Penguin Random House)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood

It’s ironic that we use robots to search for life elsewhere in the universe but if and when we do find evidence of it, a machine will tell us. And few people on planet earth are more intrigued with those missions than astrobiologist Sarah Stewart Johnson.

Based at Georgetown University, professor Johnson works closely with NASA on the design, build and operation of robotic systems being sent to Mars to try to discover life, past or present. The latest American suite of interplanetary robotic life hunters is called Perseverance, with a launch window between July 30th and August 15th. Over the years as she has teamed up to worked on this epic quest Sarah Stewart Johnson has also kept a notebook. And lucky for us she has just published her thoughts and experiences these in a fascinating book called Sirens of Mars: Searching for Life on Another World. I asked how she would like to be the leader of one these missions:

JOHNSON: You know, I am just captivated by this idea of are we alone, and searching for life in the universe, and these big questions. You know, where did we come from? And why is there something and not nothing? Did that something from nothing, did it happen once? Or did it happen time and again? And we're at this moment in human history when we have the tools to answer those questions. And the idea of leading a life detection mission, someday just would be the most thrilling thing ever. I just feel so driven to try to get to answers to those questions. And now we have a way to do that with instruments and with planetary missions.

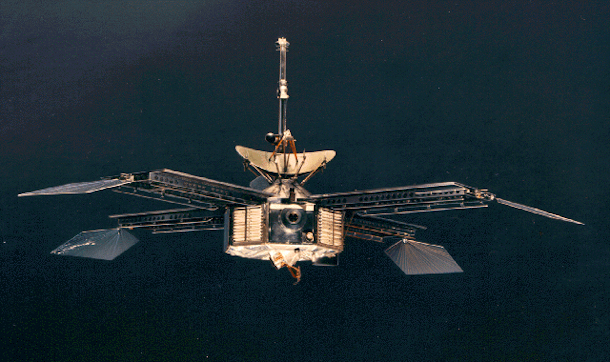

CURWOOD: Speaking of instrumentation, the first successful flyby of Mars happened in 1965. We're talking about more than 55 years ago. Sarah, give us, please, a brief history of the missions to Mars that have happened since.

JOHNSON: So, this was just a watershed moment, all of a sudden, we just went to Mars. We had our first flyby mission in 1965, the Mariner 4 mission. And this mission was just very small, it was about the power of a pocket calculator. And it was designed to make a number of measurements about the environment. And it also collected 21 photographs of the planet's surface, and each one of those took eight hours to relay back to Earth. And when those images were put together, it was just staggeringly disappointing because one of the things that those images revealed was that the surface of Mars was covered with ancient craters. And this meant number one, Mars had no plate tectonics and number two, there was no fluid erosion of any sort that would have erased those craters, and it meant the surface was ancient and there had been no water there and it was just pockmarked, like the moon. And we just really were not expecting that. I'm not sure we knew what we were expecting. But it was just this hard moment, and the New York Times even declared that Mars was a dead planet at that point. Fortunately, we didn't cease from exploration, you know, we continued to go back, we sent more flyby missions, two in 1969. 1971, we had Mariner 9, which was the very first mission to go into orbit. And it made a number of tremendous discoveries. But one of them was that the surface of Mars was covered with ancient rivers, and that there were all of these features that had to have been created by water. So, even though there was no water today, on the surface in liquid form, even though the pressure was too low, and the temperature was too cold, Mars was a much different place in the ancient past. And then not long after, later in the 1970s, we sent two orbiters, the Viking orbiters. And they each released a lander, the Viking 1 and 2 landers. And they did the very first life detection experiments on the surface of Mars. And, you know, those experiments were very confounding, the results. At first there is this enormous response from one of the three life detection instruments, to the point where some of the team members called off for champagne and cigars, thinking that they had just made the biggest discovery in the history of modern science. But then those results, they just sort of dropped off unexpectedly. And then there were the controls, which were supposed to be negative, had these big results as well in two of the three experiments. And then the real kicker was that there was a chemistry instrument that was looking for the building blocks of life, these carbon containing organic molecules, and there were none whatsoever detected. And this was perplexing because even on the moon, even on other planetary bodies, there's a ssp of rain, of these abiotic organic molecules down from space and there were just none at all, which was a big mystery. But, you know, the broad conclusion of those experiments was that no life was detected, the surface was just very bleak, you know, covered in this red dust that was the consistency of cigarette smoke.

The Mariner 4 spacecraft launched on November 28th in 1964 performed the first successful flyby of Mars. (Photo: NASA, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Well, wait, I thought there was supposed to be Martians there. And if certainly not Martians, at least there were canals that they had dug. But these flybys and these early landers don't find any of that. So if there was life on Mars, it sounds like must have happened a long, long, long, long, long, long time ago.

JOHNSON: Yeah, well, you know, I will say that we took a 20 year break from exploring Mars after those Viking missions. I think part of it was the disappointment, part of it was that there were other targets in the solar system that were becoming increasingly exciting, like the outer planets. Part of that was bad luck, there was a big mission that failed that NASA sent in the early 90s. But once we started back in 1997, NASA has been sending missions every 26 months, when the planets align on the same side of the sun. And these missions on this rough cadence of every two years have come back with astonishing findings, things that have just brought the planets into technicolor focus. And even if the surface may not be hospitable anymore, and may not be habitable because of the conditions, down deep in the subsurface, which is one of the most intriguing places to look, I think there's still a very real possibility that we could find simple microbial life. I mean, a lot of our biomass here on earth is beneath the surface in microbial form. We've barely even scratched the surface when it comes to this kind of exploration. We'll have the very first mission that will drill down to look for biosignatures or traces of life with the European mission that goes in two years, the Rosalind Franklin rover.

CURWOOD: Whoa. So you are swinging for the fences here, you could discover life on another planet in a mission that you lead. It just is really tiny, it's microbial, and way, way, way down underneath the surface. Huh.

JOHNSON: Well, maybe not even so far down, you know, even two meters down, you're below a lot of the very damaging cosmic radiation that makes it very hard for molecules to stay together at the surface. But I do feel like there's so many possibilities there, ready to be explored.

A “selfie” from the Curiosity rover, composed of 57 individual images stitched together into a panorama. (Photo: Curiosity, NASA, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So, there are four successful rovers that have wound up on Mars. What, Sojourner, the Opportunity, Spirit and wait, there's one still going, right? It's called the Curiosity? But, what were these rovers goals and accomplishments so far? And I guess it doesn't include finding life, but maybe that's a "not yet", huh?

JOHNSON: Well, so NASA kind of went back to the drawing board when we began this new era of Mars exploration in the late 90s. It was driven, on the one hand, by this idea of a better, faster, cheaper, have more missions, have them more often. And then there was also an idea that we should follow the water. Because everywhere we looked on Earth, you know, life could be very, very different in different types of environments, but the one constant seem to be water, at least at some part of its life cycle. And so NASA's new mantra, "follow the water" kicked into place. And the very first rover that went was only the very small little thing, the Pathfinder rover, it was the size of a suitcase. It landed on July 4, and it was really more of a technological demonstration to show that there was a new type of exploration. You didn't have to just look at what was right in front of your face, you could traverse and you could get to interesting scientific targets. And then the next two rovers, these twin rovers Spirit and Opportunity followed, landing in early 2004. And these rovers were about the size of a golf cart. And they landed on opposite sides of the planet. They were only built to last 90 days. But Spirit went on for four years, and Opportunity all the way until 2018. So 14 years, over 5,000 days of exploration, it went a total of 28 miles across the surface of Mars. And in that 28 miles, all of those explorations that those two rovers did, we found out some incredibly astonishing things about the planet. And that really motivated this idea of sending a scientific laboratory to the surface, which was the Curiosity rover, or also called the Mars Science Laboratory, and that landed in 2012. It was the size of a car, you know, a metric ton. Put down on the surface, landed in the base of Gale Crater and inside Gale Crater is a mountain, and it's called Mount Sharp, and it rises higher than Mount Rainier above Seattle. And it records a very big chunk of Martian climate history. And so we can look at the sediments that have been laid down, which are sort of laid down like the pages of a history book and record the environmental conditions. And we've been exploring as we've been ascending that mountain and we're still doing that today. It's been just a really exciting campaign and Curiosity has revealed that this is a habitable environment. You know, we've moved beyond "follow the water" to understanding that all the ingredients necessary for life as we know it are there, or were there in the surface of Mars and that there was all this ancient water. Water that was pH neutral, the kind of water you could drink a glass of, had you been standing on the surface billions of years ago, you know, rushing by. And streams, you know, there could have been a big lake that filled Gale Crater, the top of the mountain might have even stood as an island. We've gone back and we've found those organic building blocks of life, those organic molecules have been detected by the Sample Analysis at Mars instrument on the Curiosity rover. And I've been fortunate to work as part of that instrument team. And so we've just done some really astonishing things there with Curiosity. And now it's time to send Perseverance.

Curiosity’s view of Mount Sharp in Gale Crater. (Photo: Curiosity Rover, NASA / JPL-Caltech, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Perseverance, so what is in Perseverance?

JOHNSON: So, Perseverance in some ways, looks just like Curiosity. It's built on the same chassis, which saved a lot of money and a lot of design features. It'll land in the exact same way. Well, a little bit more refined. We're getting much better at targeting little landing ellipses, these days, but Perseverance has a different set of instruments. So, seven instruments that are really targeted towards spatially resolving and honing in on the best samples to collect. Because what Perseverance is doing is it's kicking off this breathtakingly ambitious campaign to return samples of Mars that are carefully selected to Earth. And it's going to take three missions to do it, and a lot of international cooperation. But the idea is that Perseverance will collect a few dozen samples about the size of a pen light, leave them in a cache on the surface, than a fetch rover will come along and pick those up and put them into an ascent vehicle. And then another vehicle will come along and collect those out of orbit and bring them back to Earth.

CURWOOD: Scientists have made plenty of guesses about the possibility of extraterrestrial life. So, what's your feeling here? This is not a scientific question. This is a feeling question. How alone are we in the universe, do you think? And if we're not, how likely are we to find evidence of life forms as close to us as Mars?

The Perseverance rover performs its first driving test on Dec. 17, 2019. The Mars 2020 mission is set to land on Mars in February of 2021. (Photo: NASA / JPL-Caltech, Public Domain)

JOHNSON: That's a great questions, Steve. And I think you're right, as a scientist, it's hard to answer because we aren't basing our feelings at this moment in data, right? But I can tell you, I feel incredibly strongly that we must keep looking. And I've got a couple of reasons for that. And of course, I would have picked a different career if I wasn't thinking that this would pay off in the end. But I think I just must underscore just how enormous that payoff would be, the idea of finding life on Mars or at another planetary target here in our solar system or beyond. So, we only have one data point for life. You know, it's the life as we know it, the life that we have here on Earth, and it's all basically the same. It's this DNA-based, carbon-based life. And it all traces back to a common origin. And as a result, I would argue that biology is largely a descriptive science. We don't have that second data point, we can't make the kind of constitutional fundamental understanding of biology. We can't make that leap yet, because we're limited. You know, we don't know if life is just a consequence of energetic systems. We don't know what paths it would follow.

Sarah Stewart Johnson is a Georgetown University Associate Professor who has worked with the NASA Science Teams for the Opportunity, Spirit, and Curiosity rovers. (Photo: Brittany Waddell)

We know that we had all the same sorts of starting ingredients that we had here on Earth, on Mars, and we know that they were there around the time that life was getting started here. And even if life on Mars had been, say, ancestrally, related to life on Earth. There were lots of rocks exchanged between the planets, especially early in their histories around the time life was getting started here. There is a chance that life just got caught from the next planet over. But even that would be remarkable, this idea of playing the tape of evolution over again and seeing what results. This idea of running that great experiment one more time would be revelatory. But I have to say the thing that excites me most is this idea of a separate genesis. A type of life that's completely different from anything that we've ever seen before. And I can tell you this, like if we find it on Mars, then you know, that's just the next planet, that's our near neighbor, it would just have huge implications, it would really imply that the universe would be positively teeming with life. You know, we're a small species in this vast universe. And our lives are just incredibly short, you know, on the scale of geologic time, and we really just have a moment to be here. And it just makes life so very precious and so very special. And we've really just got to make the very most of this one moment that we each have.

CURWOOD: Sarah Stewart Johnson is an associate professor at Georgetown University and the author of Sirens of Mars: Searching for Life on Another World. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

JOHNSON: Steve, thank you. This was such a pleasure to talk with you.

CURWOOD: And I do hope you find what you're looking for.

JOHNSON: Me too.

Related links:

- More on Sarah Stewart Johnson

- Space.com | “A Brief History of Mars Missions”

- More on NASA’s Perseverance rover

- More on The Sirens of Mars

[MUSIC: Leo Kottke, “Twilight Time” on Peculiaroso, by Morty Nevins/Artie Dunn/Al Nevins, BMG Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Anne Flaherty, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Kori Suzuki, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts. We tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth