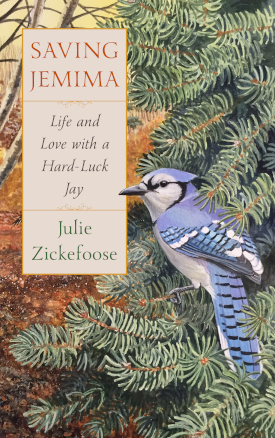

Saving Jemima: Life and Love with a Hard-Luck Blue Jay

Air Date: Week of July 24, 2020

Julie Zickefoose with Jemima, a wild blue jay she raised. (Photo: Courtesy of Julie Zickefoose and HMH Publishing)

Raising an injured baby blue jay named Jemima turned out to be one of the most challenging, and rewarding, experiences of wildlife rehabilitator Julie Zickefoose’s life. In her book Saving Jemima, which she also illustrated, Zickefoose gives a peek inside the mind of her young charge learning how to be a blue jay and shares the balance of emotions involved in raising a wild bird for release. Julie Zickefoose joins Host Bobby Bascomb to tell her story as part of the Living on Earth Good Reads on Earth series.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Julie Zickefoose is an author, illustrator, and wildlife rehabilitator. She has raised dozens of different species of injured or abandoned songbirds at her home at the Indigo Hill Wildlife Sanctuary in rural Ohio. In her latest book ‘Saving Jemima: Life and Love with a Hard-Luck Jay’ she chronicles the challenges of raising a wild bird for release and what she learned from sharing her home with a wild Blue Jay. I caught up with Julie Zickefoose as part of our Good Reads on Earth series. Julie, welcome to Living on Earth!

ZICKEFOOSE: Thank you. What a thrill to be with you.

BASCOMB: Oh, we're so happy to have you. Now you own an 80 acre wildlife sanctuary in Ohio. I'm sure there are countless species there to observe. But you invest your energy and your artistry in birds. Why birds, and how did you end up with this life where you literally have wild birds flying across your living room or perched on your lampshades?

ZICKEFOOSE: Well, I've been doing wildlife rehab with songbirds in some form since I was very, very small. I grew up in Richmond, Virginia, and my next door neighbor had 17 free roaming cats. And so I was finding broken and orphaned baby birds all the time and I couldn't walk by you know, I had to help them. In my first bit of activism as a child, I convinced her to get them all spayed and neutered, and keep them indoors. At the age of eight. I had her convinced with that, so that's what started it. And then I have been doing rehab as a federal and state licensed rehabber since about 1981.

BASCOMB: And how did this one bird a blue jay, you named Jemima end up in your care?

ZICKEFOOSE: That was the magic of Facebook. I can often reroute calls, I answer the phone a lot, and to tell people what to do with things they've found. But this one was only about 10 miles away from me. And it was a blue jay. And the woman sent me a picture of it on Facebook, and I thought, Oh, I'm doomed. So I had to I had to try it because I'd never raised a corvid before, and that was one of my life goals was to raise a corvid.

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. And as you describe it, she really became like part of your family. I mean, she pestered your dog and she developed a really special bond with your daughter. Can you describe some of those relationships that developed?

The cover of Saving Jemima: Life and Love with a Hard-Luck Jay. (Photo: Courtesy of Julie Zickefoose and HMH Publishing)

ZICKEFOOSE: Yes, well, I should preface this by saying that wildlife rehabilitators do everything they can not to turn birds into pets. And that was certainly not my goal here. I have right now a song sparrow in a fledging tent in my garage, and that bird is fed and left alone. That's how you're supposed to do it. The problem with a corvid is that they are extremely social, and without social interaction with something or someone they languish and Jemima wouldn't eat unless we were around. So she grew up in the house unlike all the other birds that I raised. So it was a quite a different situation. It was us we were her family, however imperfect and big and lumpy and non feathered and, and it worked out actually really well. She had a wonderful relationship with my daughter. My daughter was the source of music. And the this bird really enjoyed music and she would pick my daughter's iPhone, asking for another tune. It's pretty crazy and my son Liam is an artist and she would sit with him as he drew and sort through his pencils and markers and carry some of them off sometimes. So we each had a different relationship with her.

BASCOMB: And she had a specific song that she would request or that she would sing with your daughter, right?

ZICKEFOOSE: Yes, yes, it was Barcelona by Ed Sheeran. And that was just a song that got her going. She liked the beat. And when the crescendo came she'd flap her wings and screech, really.

BASCOMB: And so how did you avoid the problem of imprinting? I mean, as you said, your your goal was to release Jemima into the wild. You didn't want her thinking that she was the person?

Jemima at 16 days old, four days after she was found outside the nest. (Photo: Courtesy of Julie Zickefoose)

ZICKEFOOSE: Exactly. Yes. Well, one of the neat things that happens in bird development is that early on, they hear even in the egg, they hear the voices of their parents, and they imprint on those voices and those voices are encoded in their DNA. So that's what makes sense to them is those sounds. So what I did was as we were raising her, I kept her in the kitchen, and I kept the windows cranked open. So through the screen, she could hear the Blue Jays that were coming in to the peanuts, I put on the deck railing. She could also see them and she was raptly attentive anytime there were blue jays present. So I knew she knew she was a jay. And it was very important to maintain visual and auditory contact with blue jays, I think. But the truth is, is that these birds come to us knowing who they are. And it's our job as rehabbers to release them on time. And in a blue jay that is right around day 38 to day 40. That's when they start picking up all their own food, and they're able to feed themselves with subsidy. And that's when their social bonds begin to form. So you've got to let them go in time. You can't hold on to them too long.

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. Well, tell me about some of the challenges of having a wild bird flying around your home. I mean, It's not everyday that people do that.

ZICKEFOOSE: Yeah, it is very challenging, and especially a blue jay because they mess with everything. And they steal things and they hide things and they cache food like watermelon in your couch cushions. So you don't want that. And so what we did was we would do timeouts when she was just driving us all nuts and pestering the dog unmercifully, we would time her out and take her out to the garage and put her in the tent and just say we can't do this anymore. And so after she was released, we spent a great deal of time outdoors with her to sort of transition her, but it was really seamless. She went right back, and she had bonded with a wild blue jay by mid-August, and we released her in June. So that was really neat to see.

Jemima explores her world on Indigo Hill. (Photo: Courtesy of Julie Zickefoose)

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. And so as you mentioned, you did successfully release her into the wild, but it wasn't exactly smooth sailing. What happened with her once you did release her?

ZICKEFOOSE: Yeah, well, the whole reason I had her is that she was on the ground and sick when she was found and she had been left all day, I am of the belief that birds will kick babies out of the nest that are not quite right. I once tried to raise a carolina wren that was the last to fledge from its nest and the parents had left it behind. And I found out when I set into raising it, that it had a tremor, and which was then diagnosed as a brain tumor. So it was heartbreaking. But the parents know. The parents just know when a bird is not right. So I think what had happened is she was ill, the parents knew that they were like, not going to waste any time on this one. And so she came to me sick, and I didn't know it until the illness blossomed after her release with the stress of release and being out in the wild. So then I was faced with having to medicate a free flying wild bird, which was very interesting.

BASCOMB: And how did you do that?

ZICKEFOOSE: I did that by training her to come into food and water dishes. And so I medicated her water, I sweetened with stevia so she wouldn't taste the bitterness. And then I also medicated her food. And we kept that bond going and I kept her coming in for food and water many times a day. And I kept that up for three unbelievably stressful weeks where she's flying free and I'm just hoping that she keeps coming in.

Not all of us are lucky enough to have a live-in personal chef, but Jemima was. (Photo: Courtesy of Julie Zickefoose)

BASCOMB: So, yeah, now you have rehabilitated more than a dozen different species of birds but from what I understand corvids, the family that includes crows and ravens, blue jays, like Jemima, they're more intelligent than your average bird. Does that ring true to you after living with both a blue jay and all of these different types of birds?

ZICKEFOOSE: Oh, yes, absolutely. I've actually rehabbed about 25 different species of songbirds. And it's striking how much more involved it is to raise a corvid because they are so intelligent and so needy of social interaction. So and that's what makes them fun. You know, that's what makes them really a wild ride to raise.

BASCOMB: Blue jays don't have the best reputation even among birders. They're sort of loud, they're territorial, I think they're sort of seen as the bully on the playground at the bird feeder in the yard. How do you respond to that kind of sentiment?

Jemima formed a strong bond with Julie and her family, but still retained her identity as a wild blue jay. (Photo: Bill Thompson III., courtesy of Julie Zickefoose)

ZICKEFOOSE: Well, I, I just think it's, it's ridiculous actually. Because I mean, I mean, I know people in my part of Southeast Ohio who actually shoot them off their feeders, illegally, you know, a lot of people think, "Oh, well, they're pigs, they're hogs." They come in. And what they're doing is they fill their gular pouches, their throat area with seed, and then they go and cache it, they hide it in a bunch of different places. But what's kind of neat about that is that they're often feeding small rodents, they're feeding other birds who watch them cache, you know, so it's not necessarily just that they're pigging all the seed. So I think they're maligned unfairly.

BASCOMB: And surely some of those seeds they're caching if they're the right type will grow up into trees and support the habitat.

ZICKEFOOSE: The oak forest grows through the forgetfulness of blue jays. Yes.

BASCOMB: That's a nice sentiment.

Blue Jays serve as the alarm call of the neighborhood, often the first to alert other birds to the presence of a dangerous predator. (Photo: Dave Doe, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

ZICKEFOOSE: Yes.

BASCOMB: And you write that in several instances, Jemima would actually sing I think a lot of people maybe don't know that blue jays and other corvids actually have songs. Can you describe her songs for us?

ZICKEFOOSE: Beautiful, beautiful little whisper songs and quite typical of her own species. They were perfect actually they sounded just like a wild blue jay's whisper songs but it's a sort of a sort of a sotto voce burbling series of squeals clacks clicks, whistles, little flourishes and trills and it's quite surprising actually, that something like that can come out of a blue jay. It's a lovely, lovely sound. I have recorded wild blue jays they will do imitations of other birds. And actually, this spring, I witnessed something that was one of the most remarkable things I've ever heard. There are crows in our area that attack hawks, and they make a certain you know, call when they're attacking the hawk. It's kind of a, kind of a strange little call. And this blue jay was sitting in the top of a birch tree in my yard in March. And it started off with the scream of a red-shouldered hawk, which blue jays are known to do. They imitate hawk calls. So it went: Kiyaah, kiyaah, and then it went caw caw caw, rrrrik rrrrik rrrrik, kiyah, kiyah. So it did the entire litany of the attack. It did. Here's a red-shouldered hawk. Uh oh, here comes some crows. They're calling, now they're diving on it. And then the hawk screams again.

BASCOMB: Wow.

ZICKEFOOSE: And it was just, to me it was like a performance piece. And it was surprising to me, but I shouldn't have been surprised because this is a wonderful brain that's operating here.

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. And how did you feel the day you let Jemima go?

ZICKEFOOSE: I felt exultant. It was wonderful. She was so smart about it. She stayed put in the same japanese maple tree all that day, and made only very brief forays out from it. She ate from her bowls and drank from her water and it just went really well it was the smoothest release. I've ever had.

BASCOMB Well, wildlife rehabilitators like yourself all over the country are doing this wonderful work to save individual birds. But where does that fit, do you think, in the larger context of conservation? From what I understand bird populations as a whole, are really in a crisis. The number of birds in the US and Canada is down by nearly 30% in the last 50 years.

ZICKEFOOSE: Yeah, well, I think rehabbers have a great job to do in educating the public. When I was doing a lot of songbird rehabilitation in Connecticut, 90% of the birds I took in had been injured by cats and any rehabber will tell you that that's the most heartbreaking thing that we face is that people allow their cats to roam free. That said, I do think that strides have been taken. I think that people are starting to wake up about free-roaming cats and birds. They're starting to wake up about buildings: All new constructions in New York City are now going to have to have bird safe glass. So we're out there, you know, educating people about this, and I have friends who are in Cleveland getting them to turn out the lights during migration. It's a wonderful, wonderful thing. So rehabbers have a tremendous job to do in keeping the public educated. That said, I think on a population level, wildlife rehab is really for people. I don't think that we make much more than a drop in the bucket unless you're talking about a really rare species. But the difference we make is in the hearts and minds of the people who bring these birds in, and who then follow their story and who then are more likely to stop to help the next time. So the thing to do is to be kind to everyone who comes to you with a baby bird question and this time of year with 5000 Facebook friends, that's all I get, is baby bird questions.

The bright blue of a blue jay’s tail comes from a surprising source: black pigment arranged in specific microscopic patterns which bend light waves to reflect blue wavelengths. (Photo: Dennis Murphy, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Now over the course of your time with Jemima, you spent countless hours as you've described, feeding, observing, you had to consult with veterinarians when she got sick. You took photos of her. What do you feel that you learned as a scientist, as an ornithologist from that experience?

ZICKEFOOSE: Oh my goodness, I think the thing that really floats to the top for me is that I gained an even greater respect for the things that birds come programmed with, the things that they already know, the self identity that is so strong in their makeup, even when they're tiny and featherless. They already know they're blue jays. And they do everything they can to get with their own kind, no matter how strange and artificial their upbringing, so the bird knows what it should be and how it should act. And it's our job when we're caring for them to listen to that little voice that is telling you, here's what I need, and you need to rise to that and follow your instincts to do that. I learned a lot about myself. I learned about you know, how deep is my passion for birds, and how cleansing it is and how it's my salvation really, nature is, I can, there's very little that can't be fixed with a five mile run, you know, It's out in out in nature and it's I was you know, these are these are tough times. And I think that if you can't walk out your door and get to nature, get in your car and drive to it, just get yourself out it will fix you.

BASCOMB: Julie Zickefoose is author of the book Saving Jemima: Life and Love with a Hard Luck Jay. Julie, thank you so much for sharing Jemima's story with us.

ZICKEFOOSE: Thank you Bobby. This has been a great honor.

Links

Click here to learn about the blue jay’s “whisper song”

Read more on Julie’s popular natural history blog, and see a video of Jemima singing

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth