July 24, 2020

Air Date: July 24, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trump Rolls Back National Enviro Policy Act

View the page for this story

The Trump Administration has finalized a weaker interpretation of NEPA, the National Environmental Policy Act. NEPA requires that the federal government study the potential consequences of major infrastructure projects like pipelines, dams, and highways, and consider less harmful alternatives. Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau joins Host Bobby Bascomb to explain the significance of the rollbacks. (09:03)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s Beyond the Headlines, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss the environmental justice legacy of John Lewis, civil rights leader and Congressman. They also cover the possible lasting impacts of low ridership on public transit due to the pandemic. (04:13)

"Goatscaping" for Chemical-Free Weed Control

/ Aynsley O'NeillView the page for this story

It’s midsummer and the weeds are booming, but pesticides and backbreaking labor aren’t the only remedies. A herd of hungry goats will happily mow down invasive blackberries, kudzu, and even poison ivy. Living on Earth's Aynsley O'Neill took a trip to Georgetown, Massachusetts to watch some “goatscapers” on the job. (08:38)

Farmland Losing to Development

View the page for this story

In the last 20 years, more than 11 million acres of U.S. farmland have been converted, fragmented or paved over by development projects, according to a new report by the American Farmland Trust. Senior advisor and co-author of the report Julia Freedgood joins Steve Curwood to discuss this threat to local and regional food systems. (07:20)

Crab-Eater Seals Take a Break

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

The South Shetland Islands are home to sea birds, penguins, and a variety of other Antarctic wildlife. Living on Earth's Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender shares a story of the crab-eater seals relaxing on the Antarctic ice. (03:04)

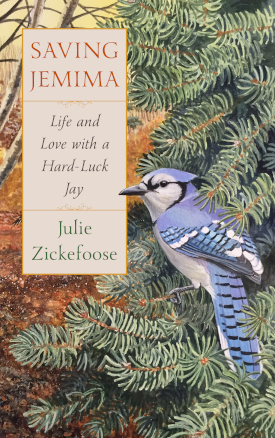

Saving Jemima: Life and Love with a Hard-Luck Blue Jay

View the page for this story

Raising an injured baby blue jay named Jemima turned out to be one of the most challenging, and rewarding, experiences of wildlife rehabilitator Julie Zickefoose’s life. In her book Saving Jemima, which she also illustrated, Zickefoose gives a peek inside the mind of her young charge learning how to be a blue jay and shares the balance of emotions involved in raising a wild bird for release. Julie Zickefoose joins Host Bobby Bascomb to tell her story as part of the Living on Earth Good Reads on Earth series. (15:53)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Julia Freedgood, Pat Parenteau, Julie Zickefoose

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender, Aynsley O’Neill

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The Trump Administration has rolled back rules for a 50 year old bedrock environmental law, the National Environmental Policy Act.

PARENTEAU: It's what we call the Magna Carta of environmental law because it's a basic statement of principle and policy. And it's sweeping in its scope. It's really designed as it says, For man and nature to live in productive harmony.

BASCOMB: Also, some homeowners are ditching the lawnmowers and herbicides to get at noxious weeds in favor of alternative landscaping options. Goats.

MICHELLE: As soon as they get in there you’ll see they'll just start rummaging around and eating what they like first, which is probably the poison ivy. And then they'll go to what they like second. Just like, you know, the good stuff on our plate first. [GOAT SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Trump Rolls Back National Enviro Policy Act

Speakers from the Standing Rock Sioux Nation at a Minnesota rally against the Keystone XL Pipeline. In 2017, Federal Judge James Boasberg ruled that the construction the pipeline violated NEPA. In 2020, the pipeline was shut down. (Photo: Fibonacci Blue, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb in for Steve Curwood.

A bedrock conservation law, the National Environmental Policy Act or NEPA, is the latest environmental regulation subject to rollbacks from the Trump administration. For 50 years the law has required that the federal government consider the potential consequences of new infrastructure projects like pipelines, dams, and highways. They must evaluate how those projects might impact human health, cultural resources, and endangered species to name a few and consider less harmful alternatives when possible. Now, claiming to slash costs, delays, and red tape for major infrastructure projects, the Trump Administration has finalized a weaker interpretation of NEPA. The new rules would narrow the types of impacts studied, set a higher bar for public comments, and exempt some projects from review entirely. Here to discuss the rollback is Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau. Pat, great to have you back on Living on Earth!

PARENTEAU: Thank you, Bobby. Good to be here.

BASCOMB: I understand that it removes, basically, the requirement for analysis of cumulative or indirect impacts on the environment. So, for instance, you know, climate change. I mean, would NEPA ever apply to climate change, it's always going to be somewhat indirect, isn't it?

PARENTEAU: Yes, it isn't a direct, immediate effect. The cumulative loading of carbon in the atmosphere is what's causing global warming, causing sea level rise and all the rest. So this rule actually does something quite different than the proposal. The proposed rule simply said, cumulative impacts will not be considered. In this rule, the final rule, it says, it's up to the individual agencies to decide. So the rule is introducing a lot of uncertainty into the process. We now have a large number of judicial decisions, saying, of course climate change must be taken into account. And many of those decisions have overturned attempts by the Trump administration not to consider climate change in oil and gas leasing, coal leasing, gas pipelines and so forth. So the courts have uniformly said, of course you have to take climate change into account when you're writing your environmental impact statement. This rule now says, well, generally you do not, but we're leaving open the opportunity for individual agencies to do so in certain cases. All of which means we're going to have more litigation over that very question. So the rule isn't settling anything. It's raising more questions than it answers.

BASCOMB: Yeah, that makes it difficult, obviously, to have this hodgepodge of interpretations. Well, let's take a step back for a moment. What exactly is the National Environmental Policy Act, NEPA, what is it designed to protect?

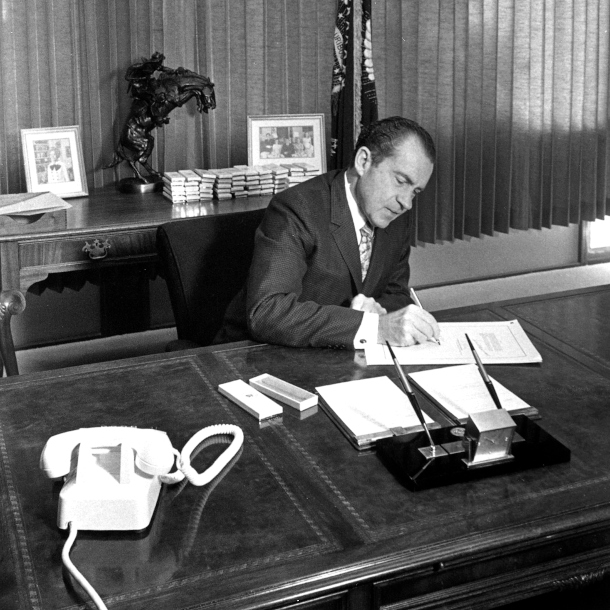

President Nixon signing The National Environmental Policy Act into law on January 1, 1970. (Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Flickr, Public Domain)

PARENTEAU: Everything! That's one of the great things about NEPA; passed in 1969. It's what we call "the Magna Carta of environmental law" because it's a basic statement of principle and policy. And it's sweeping in its scope. It's really designed, as it says, "For man and nature to live in productive harmony." So it has a lot of focus the long-term effects of the actions that we're taking now, effects on future generations was called out specifically in the law, historic sites, archaeological sites, Indian religious sites, aesthetics, you know, scenic beauty, the quality of life in inner cities and neighborhoods, green spaces. It's a "look before you leap" kind of approach to things. It's basically saying to agencies, when you think about building a highway, for example, why don't you think about other means of reducing traffic, because all highways do is generate more traffic, they don't really solve congestion. They sometimes make congestion worse. So NEPA was aimed at that kind of thinking, that there's only one way to control a flood, which is to build a dam. Well, no, not really. You could move people out of the floodway, and then you wouldn't have to build a dam. So it isn't just parks, and wilderness and wildlife. All of that's important too, but NEPA touches on virtually all aspects of the quality of life.

BASCOMB: And can you give us a couple recent examples of projects that have shown how NEPA can work and the potential behind it?

PARENTEAU: Yes, there are hundreds of case studies of how the NEPA process has enabled local communities to participate in decisions affecting their health and their community well-being. So NEPA is one of the primary tools that groups like those that are concerned about Keystone XL, the Dakota Access Pipeline, the recent abandonment of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, and NEPA is a handle, a tool, that the community groups use to challenge those projects, challenge the very idea that we should be building all of this infrastructure which is propelling us more in the direction of climate change, but also the way these projects are sited in their communities, the way that they take account of pollution, spills from these pipelines. That's a big concern with Dakota Access. And then on a larger scale, NEPA played a role in getting some of these, what we call, "mission-oriented" agencies, like the Forest Service, to stop thinking that all that forests are is a basket of wood for wood products, timber, and so forth and look at them as ecosystems. So NEPA is a legal tool, it's a policy tool, and it's a community action tool.

BASCOMB: Now, the Trump administration looks at these rules and says they're going to slash costs, they're going to streamline the process, put people back to work doing these infrastructure projects and just, you know, get rid of red tape. How do you respond to that argument?

PARENTEAU: Well, we hear the red tape argument all the time. The truth is, some of the studies that have been done suggest the real reason for the delay is agencies trying to cut corners and not actually follow the law, or applicants for permits not actually doing the good work they need to do to evaluate the impacts and come up with alternatives. So you can't blame the law for mistakes that the people implementing the law are making. And you can't blame the law when people try to cheat and get around the law, find loopholes. I can point to a number of court decisions, where the judges have said, all you needed to do, to the agency, is simply follow the law. That's what the judge said about the Dakota Access Pipeline most recently, he told the Corps of Engineers, here's the problems with your analysis of a spill from your pipeline that might affect the water supply for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, and you just simply didn't do it. So that's the problem a lot of times is, if you do the process right, you do your homework, the decision making should be a lot easier.

Former EPA Regional Counsel Pat Parenteau teaches environmental law at Vermont Law School (Photo: Courtesy of Vermont Law School)

BASCOMB: Now, of course, this is an election year and President Trump could have as little as five months left in office. To what degree do you see this as an eleventh-hour push to get some last minute things through and how effective might that be, given this timing?

PARENTEAU: It's clear that this is part of the President's push for energy dominance, for pushing through as many of these fossil fuel infrastructure projects as possible. It might benefit, actually, some other projects as well -- wind projects -- but the primary focus is fossil fuel projects. And it's clear that it's part of an election strategy. These proposals were made, of course, months ago, but this last minute push to get them approved and published and in effect, that's clearly tailored to the election cycle that we're looking at. So whether or not these rules will survive, of course, is a big question. I think the rule has a lot of legal vulnerabilities. And so it could be that the courts will step in as they have so many times to block what the Trump administration's rollbacks are seeking to do. And then of course, after the election, depending on how that goes, we could see other political responses to the rule as well.

BASCOMB: Mmhmm. Well, ultimately, what kind of impacts do you think these weaker NEPA rules could have on environmental conservation if they do hold up?

PARENTEAU: Well, it'll certainly make it more difficult for local communities to have a seat at the table, and to have their voices heard, and to have projects modified to reduce some of their impacts. And a lot of these communities are minority communities. So there's a very strong environmental justice component to all of this. And in fact, the environmental justice community writ large, is probably one of the most active and concerned about these rules. I think if these rules were to survive, I think it's going to actually create more delay. All of these things are subject to judicial review and challenge, over and over again, sometimes. So there are many different ways in which a rule like this is going to create uncertainty litigation, and make it actually more difficult to get things done. There could be ways of improving the rule and the NEPA process. I'm sure there are. But this rule isn't the way to do it.

BASCOMB: Pat Parenteau is a professor of environmental law at Vermont Law School. Pat, thanks so much for your time today.

PARENTEAU: Thank you, Bobby.

Related links:

- NY Times | “Trump Weakens Major Conservation Law to Speed Construction Permits”

- Washington Post | “President Trump Overhauls the National Environmental Policy”

- NPR | “President Trump Overhauls Key Environmental Law to Speed Up Pipeline and Other Projects”

[MUSIC: Joshua Redman “Floppy Diss” on RoundAgain 9feat. Brad Mehldau, Christian McBride, Brian Blade), Nonesuch Records Inc.]

Beyond the Headlines

Civil rights advocate and Congressman John Lewis passed away on July 17, 2020. He was also known as an advocate for environmental justice. (Photo: Mobilus In Mobili, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0).

BASCOMB: It's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby. And for very good reasons we've heard so much in the form of tribute about the late congressman John Lewis. Most of it has focused on things other than the environment. But, I think we owe a little tribute to John Lewis, because he was a steadfast advocate of environmental laws and environmental justice.

BASCOMB: And I believe we have a bite of the late John Lewis to play here. Let's have a listen.

LEWIS: Combating climate change is not a Democratic or Republican issue. It is the question of preserving this little piece of real estate that we call Earth for generations yet unborn.

BASCOMB: Now, he was a 17-term congressman from Georgia, right? Tell me more about his environmental justice legacy.

DYKSTRA: He's - from the very beginning - we're talking about more than three decades ago, Congressman Lewis sponsored environmental justice legislation, he spoke as passionately about pollution in poor and minority communities, as he did about any other aspect of civil rights. Overall, his League of Conservation Voters score in 17 terms in the House of Representatives was 92%. That's a pretty remarkably high number for so long, with a congressman that was involved in so many other things beyond the environment.

BASCOMB: And I understand that you actually bumped into him a few times since you live down in his region.

DYKSTRA: Right. When I first moved to Atlanta, John Lewis was my congressman. And since then, I've run into him on planes, in airports, at events, and I was just blown away that someone so prominent, a big politician and a celebrity, actually cared what I was saying to them. At one point, John Lewis was listening to me so intently and caring about things that he almost missed this flight back to Washington. He's a guy who really cared. I've heard so many similar stories about him. And there are few, if any, that are his match in Congress, or in any phase of government.

BASCOMB: Such a loss, but what a legacy he leaves behind. Well, what else do you have for us this week, Peter?

DYKSTRA: A lot of folks have talked about greenhouse gas emissions being sort of the tiny silver lining in the toxic cloud of Coronavirus, because with so many people sheltering at home, so many people not going to work, travel is way down in the era of Coronavirus. But, that might be canceled out by an equally dramatic drop in mass transit ridership.

BASCOMB: Hmm, that's true, I suppose. Fewer people are commuting to work on the train and bus and things. What's that going to mean going down the road in the future when we do want to get back to work?

DYKSTRA: Well, with fewer people crowding into trains, and you can understand with Coronavirus why people are avoiding crowds like that, they're also just not going to work as you said. But according to Inside Climate News, this could trigger some massive cuts in federal aid since some federal aid money is largely pegged to ridership numbers.

With fewer people taking public transit, federal funding could be cut for public transportation in the U.S. (Photo: Alexander Rentsch, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Ah, so you're gonna see a drop in financial support for public transit. I mean, that's gonna lead to what, cuts in services, I would guess.

DYKSTRA: Cuts in services, some bus lines may be cut out completely. A couple examples - out in the San Francisco area, BART- Bay Area Rapid Transit - runs trains and buses. They anticipate a half billion dollar loss in federal funding. While across the country in New York City with its massive mass transit system, they expect a $10 billion cut. That's billion with a "B".

BASCOMB: Hmm, that's huge. That's a huge amount of money. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- COLORLINES | “EPA Pays Tribute to Rep. John Lewis and Environmental Justice”

- Forbes | “John Lewis and His Environmental Legacy”

- Inside Climate News | “A Plunge in Mass Transit Ridership Deals a Huge Blow to Climate Change Mitigation”

[MUSIC: Jeff Little, “E.M.D.” on Piano Man from the Blue Ridge, by Grissman]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Local food needs local farmland but there’s less and less to go around. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joshua Redman “Floppy Diss” on RoundAgain 9feat. Brad Mehldau, Christian McBride, Brian Blade), Nonesuch Records Inc.]

"Goatscaping" for Chemical-Free Weed Control

Goats eating noxious weeds and brush at a job site in Newbury, Massachusetts. (Photo: Aynsley O’Neill)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Well, it’s mid-summer and for many of us that means yard work. Mulching, watering, pulling out weeds. And for those unfortunately stuck with poison ivy the task of getting rid of it typically means hours of back breaking, itchy, work or toxic chemicals. But there is at least one lesser known alternative. Goats. Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Nelll has the story.

[ SFX FARM ]

O’NEILL: The 55 acre Great Rock farm in Georgetown, Massachusetts has more than 130 goats and twice as many sheep.

[SFX dogs, sheep, goats]

O’NEILL: Michelle Aullson greets me with a huge smile. She grew up on this farm surrounded by ducks, goats, sheep, herding dogs and horses. And after living for some time in Washington D.C, she decided to come back and help out the family business: Goats2go.

MICHELLE: Aynsley nice to meet you. I am sure the dogs told me you were here. These are our two australian shepherds that herd the animals. Banjo he is 8 and Jack is 3. [bark] hey!

O’NEILL: Michelle is wearing black yoga pants, sneakers and her blonde hair is in a tight ponytail. We walk together towards a goat pasture, surrounded by a white fence. As we enter the enclosure, Michelle pats a shiny black goat and introduces us.

MICHELLE: So this is Squeeks she is five months old, so squeeks will probably follow us all around. And that’s miss piggy.

O’NEILL: Aw miss piggy that’s cute.

MICHELLE: And that’s Miss Piggy’s brother up on top of the hay, the highest point the goats always want.

O’NEILL: She is able to point out every goat by name and introduces them like they’re her extended family.

Michelle Aullson (center) is the Events Manager at Great Rock Farm and the daughter of Goats to Go founders Aileen and Alan Aullson. Here, she shows Producer Paloma Beltran (left) one of the many goats at Great Rock. (Photo: Aynsley O’Neill)

MICHELLE: Patches are coming out of the barn right there.

O’NEILL: Oh

MICHELLE: He’s like somethings happened. This is Oreo she is the best doe with the babies, she had 4 this year. This is one of her babies from a few years ago. That's a crazy goat right there. That’s Giraffe because he looked like a giraffe when he was a baby, he’s gotten bigger now but. And this is Little Missy and then there’s a few other ones right here that were my little tiny ones.

O’NEILL: Michelle was present for the birth of many of these goats.

MICHELLE: And they’re jumping around the moment they’re born they’re really cute, sometimes they are the size of a water bottle with little legs, a St. Algene bottle.

O’NEILL: After getting to meet the furrier side of the Aullson family we hop onto a pickup truck to see some goats at work.

[SFX CAR DOORS]

O’NEILL: We arrive at our destination in the neighboring town of Newbury, Massachusetts. There’s a green two floor suburban home with about a 200 sq ft yard. A yellow trailer filled with goats is parked in the driveway. The area where the goats will be working is filled with rocks, trees, and plenty of noxious weeds like poison ivy, poison oak and sumac. Jamie Genest, the head farm caretaker and sheep herder, starts sectioning off the backyard.

[SFX FENCE]

GENEST:. Well basically what we have to do is we clear a path, so that we can set the electric fence up because the fence itself can't hit anything or it'll ground it out. And here is your electric fence with your rod battery.

O’NEILL: He puts an electric fence around the work area to keep the goats from being bothered by dogs and to keep the flower beds from being bothered by the goats. Inside the fence Jamie has set up a pool of water to make sure that the goats stay hydrated while they're on the job. To the side, there’s an open tent for the goats to rest under, in case they start to overheat. Jamie makes sure that these Goats2Go are always good to go.

[SFX GOAT BLEATING]

O’NEILL: Homeowners Tracy and Peter come outside to greet the crew and get a peek at the goats. Peter says he had seen advertisements for Goats2Go and just decided to give it a try.

FRANGOS: It might be a nice easy way to take care of getting this area landscaped and get rid of the brush with a natural process. It's not going to be cheap, but it's not going to be more expensive and it's, you know, environment neutral. So it's not something I can do because it's Poison Ivy and I don't want to be in poison ivy. And it's effective and good for everybody and the goats get a meal out of the deal.

O’NEILL: Goat landscapers are a novel and as Peter alluded to, a fairly expensive alternative. The cost of hiring Goats2Go is more than $500 dollars per grazing job. The most popular and cheapest way to eradicate weeds is the use of herbicides. But some herbicides are non-selective, meaning they not only kill the intended plant but everything around it including any insects that happen to stop by for a landing. And long-term exposure to herbicides has been linked to many health concerns in humans, including cancer. So goat landscapers aren’t just cute furry friends, they make an honest living as an eco-friendly alternative.

[SFX GOAT NOISE]

[ https://freesound.org/people/Bidone/sounds/66762/ ]

O’NEILL: The goats are eager to get out of their trailer and explore. After making sure everything is set up properly, Michelle explains what’s about to happen.

Peter Frangos (property owner, left), Alan Aullson (Goats to Go founder, middle left), Paloma Beltran (LOE associate producer, middle right), and Aynsley O’Neill (LOE associate producer, right). (Photo: Courtesy of Paloma Beltran)

MICHELLE: Usually the trailer comes open and they just come out and some of them just faint when they come off the trailer because they're all excited or nervous.

O’NEILL: Fainting goats also known as myotonic goats, have a natural mutation in their genes which cause their muscles to stiffen up when they are startled.

MICHELLE: And as soon as they get in there, you'll see, they'll just rummage around and start eating what they like first, which is probably the poison ivy. And then they'll go back to what they like second, just like how we like, you know, the good stuff on our plate first.

[SFX GOAT BLEATING]

O’NEILL: The trailer opens up and Jamie starts latching ropes onto the collars that all of the goats are wearing around their necks. They seem eager to hurry down the small slope of grass onto the overgrown area of the yard. I was given the honor of guiding one of the goats to the weed buffet.

MICHELLE : So this is what you call a walk in job, you gotta hand lead all the goats in...

O’NEILL: I have grabbed on to a goat but I'm a little I'm not sure I've directed in the right path. He's just wandering around a tree right now. So I'm just gonna pull him. teensy bit. Come on, come on, come on. Oh, I should grab some goat treats eii. As soon as the goats stepped inside the fence, it wasn't even difficult to pull them anymore. It was like the goat knew exactly where to go.

[SFX GOAT BLEATING]

O’NEILL: Some goats head right towards the rocky area, others huddle inside the tall brush as though they’re all eating from a family table. Two black and white spotted goats are so deep in the bush that I only see their horns peeking out from between the leaves.

Goats like to eat high-growing plants and can digest noxious weeds like poison ivy due to the acidity in their stomach. (Photo: Aynsley O’Neill)

MICHELLE: So goats are what you call high browsers and then they eat low grass if there's nothing else there. But they don't care for grass, they like shrubs and they like these bushes right here.

O’NEILL: Other animals like sheep and cows are also grazing animals, but Michelle says goats have several advantages when it comes to eating noxious weeds like poison ivy.

MICHELLE: They have teeth on the bottom and a soft pad on the top which they can even eat stuff that's thorny, and in woody bark and everything. They have a very acidic stomach so when they eat something, they break it all down. When they poop the other end, they don't regerminate what's already there. Horses and cows have seeds in their poop goats do not and neither do sheep. But the goats just happen to love it and I think it has to do with their digestive system and what they like to eat.

O’NEILL: It will take the goats about three days to finish clearing out this space. But it’s not one and done. Noxious weeds will grow back. It will take the goats several sessions to starve the plant, blocking it from the energy it needs to survive and weakening its roots. Although goats are not able to eradicate weeds in just one sitting, they are able to remediate soil by churning it with their hooves and fertilizing it with their waste. After these biomachines are done cleaning up the overgrown shrubs, Michelle will be ready to take them back to their home at the Great Rock Farm. And while these goatscapers won’t take over the jobs of human landscapers for good, Goats2Go provides an alternative to those wanting to get rid of weeds and shrubs in a more natural, goaty sort of way. For Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill in Georgetown, Massachusetts.

[GOAT SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Our report on Goatscapping was produced with help from Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

Related links:

- Learn More About GoatsToGo

- Gardening Channel | “Goats for Weed Control: Everything you Need to Know, Including How to Rent Goats”

- NPR | “Go Ahead, Little Goat, Eat Some Poison Ivy. It Won’t Hurt a Bit ”

[MUSIC: Ma-Duncan-Meyer-Thile, “Goat Rodeo” on The Goat Rodeo Sessions, Sony Classical]

Farmland Losing to Development

More than 11 million acres of U.S. farmland have been converted, fragmented or paved over by development projects in the last 20 years. (Photo: Thobias Stromberg, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: The U.S. has lost more than 11 million of acres of farmland over the last 20 years. Of special concern is the loss to low density residential development at the edge of urban and suburban areas. A series of studies by the American Farmland Trust show that agricultural land is being increasingly converted, fragmented, or paved over. Threatening the integrity of local and regional food systems. Julia Freedgood is a senior advisor with American Farmland Trust and a co-author the most recent report. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: Just how important are local food supplies?

FREEDGOOD: I think tremendously important, quite frankly. And I think that COVID-19 has really pointed this out. You know, it's not that we need to replace the global food systems or domestic food systems. But when you have a shock, like a pandemic or an extreme weather event, the fact that you can pivot to local and regional food supplies is incredibly important for the resiliency of our food system and also to make sure that everybody in your community can get fed. I think, you know, a lot of what's driven sort of a resurgence in that kind of direct marketing is the flavor, the freshness, the quality, and also the relationship with the farmer and the transparency so that you know where your food is coming from, and you know how it's grown and you know who the people are. It's better for cooking. It's better for flavor, but it's also sort of better for building a sense of community.

CURWOOD: Tell me where should we go from here. How do the ways we get our food need to change in your opinion?

Fragmentation of farmland by development in Florida. (Photo: Art01852, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

FREEDGOOD: I think we really need to start looking at our policy framework. I think our policy framework has served a certain portion of agriculture very well. It's very efficient. And I think efficiency is, you know, a good thing. But it's left out the majority of farms and ranches in the country. When it comes to growing food for your community, then you're competing with a global food system, prices are really low, it's very, very hard to make ends meet. Fruits and nuts and vegetables--all of those are considered specialty crops, rather than, you know, corn and soy beans and our kind of dominant agricultural production in this country. I think we need to really look at what are we going to do to make sure that we're protecting farmland in our own communities, our states and our communities? And I think we need to start looking at how do we incentivize that kind of production so that we have this kind of resiliency, so that we're ready for everything that comes whether it's a pandemic or whether it's climate change.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about this project Farms Under Threat.

FREEDGOOD: We really wanted to look at the quality of the land for our food supply, as well as for all of agriculture. So what we were able to do was look at sort of the highest quality land in each state, and then what had happened to it in terms of development patterns. And that's where we had become aware that there was sort of this insidious pattern of sort of fragmentation in rural communities, and nobody was measuring it or tracking it. So we came up with a methodology so that we could sort of see the impact of lower density kind of development happening sort of across the countryside.

CURWOOD: In other words, sprawl.

Many of the farms threatened by low-density residential development are local, direct-to-consumer farms. (Photo: Gemma Billings, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

FREEDGOOD: Not even as concentrated as sprawl. You know, what you'll see is one house per maybe five or 10 acres in an area, and maybe they're having some horses or some llamas or something like that, looks kind of like a farm if you're, you know, in outer space and looking down for spatial mapping. But in terms of economy, you suddenly have a different kind of an enterprise happening. It's not a commercial enterprise. And so things like the infrastructure to support agriculture, your feed stores, your supply stores, those kinds of things start to go out, and you start to get replaced by people, you know, have a couple of horses in their backyard. So it's not exactly sprawl as we think of it, you know, as urban sprawl with malls and everything around the city, but it still can have a detrimental impact on the agricultural community and economy.

CURWOOD: So tell me about these urban adjacent farms that are most threatened by development. What do these farms tend to look like and how does low density residential development affect them?

FREEDGOOD: That's such a great question because I think it's a little bit of a double edged sword. We're in New England, right? And so you see a lot of small farms kind of embedded in communities. Often these smaller farms that are metro-adjacent are doing direct to consumer marketing or supplying farmers markets and community supported ag and those kinds of things with a benefit of a population that really wants to support local farmers and local food. But I think the pressure is that there are a lot of people who already live there. There's already you know, kind of a suburb, usually a suburban economy happening. And so the pressure to develop for something other than a farm is really great and it drives land values up often beyond what a local farmer can afford to pay.

CURWOOD: And how do all your findings now fit into the current state of the of the agriculture industry?

FREEDGOOD: Well, I think that the pandemic has really sort of showed the fault lines and how overly consolidated we've become. It's not that we have a supply problem right now. What we have is a distribution problem, a supply chain problem. So you see this sort of awful juxtaposition of, you know, farmers either having to euthanize their animals or dumping milk or leaving crops unpicked, when at the same time you have these really long lines for food banks, and suddenly you have all of these people who are unemployed and food security has become a really serious issue. I hope that people are starting to take this seriously. I hope that some of the things that we've been talking about for decades about consolidation in agricultural industry and consolidation in cropland in particular, you know, farmers and ranchers and farm workers, they're essential parts of our service economy, of our labor force, right? Like, suddenly people are like, Oh my goodness, we really need to know where our food is coming from.

CURWOOD: And tell me about your experiences as the coronavirus pandemic rolled out? What was it like for you in terms of getting food where you are in Western Massachusetts, the rural part of Western Massachusetts?

Local farmers harvest shungiku microgreens in Powhatan County, Virginia. (Photo: US Department of Agriculture, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

FREEDGOOD: I would say I have felt extremely lucky. The disruption was definitely felt here too. But within a week or two, there were food deliveries. So I could just sign up online and have, you know, my spinach and carrots and onions and stuff just delivered to my house. We have local farms that have gone to, you know, curbside pickup and on-farm delivery. I'm in walking, you know, I can walk down the street and get my eggs and some meat. I ordered a pound of carrots and it came back as one carrot. So I learned something about how you order food. But I just I feel incredibly blessed to have, you know, to live in a place where we've been working on sort of local-regional food systems for a long time, and therefore we could very quickly pivot.

BASCOMB: That’s Julia Freedgood with American Farmland Trust speaking to Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

Related links:

- American Farmland Trust | “Farms Under Threat: The State of States”

- Atlanta Journal-Constitution | “New Report Says Georgia Farms Are Under Threat”

- The Patriot-News | “Where Does Pennsylvania Rank in Farmland Loss, Protection?”

[MUSIC: Matt Haimovitz/Christopher O’Reilly, “Weird Fishes/Arpeggi” on Shuffle.Play.Listen, by Radiohead, Oxingale Records]

Crab-Eater Seals Take a Break

A crab-eater seal slides on the ice in front of the remnants of a shipwreck. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

BASCOMB: The South Shetland Islands in the Antarctic are a haven for a huge variety of wildlife including sea birds, seals and penguins. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender has more.

Do-nothingCrabeater SealSouth Shetland Islands© 2020 Mark Seth LenderAll Rights Reserved

LENDER: Two crabeater seals, one older one younger (related perhaps) drag themselves out, and up, and onto the worn basalt crowning from the sea just beyond the fast ice. And lay down there. The head of the one to the tail of the other fitted, like parts, of something larger. Except there is no room for anything larger. Them, it suits. One yawns, palate as purple as a lilac tree in bloom, teeth shaped like nutmeats but sharp and meant not to be chewed but to do the chewing. Potentially. Because, after that yawn... Inanimate. Not so much as a shrug. Crabeaters, taking a break.

Two crabeater seals bask in the Antarctic sun. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

They will take one anywhere they can. They have no country. No allegiance of terrain except for an easy in, and an easy out. The chinstrap penguins nearby, they are the regulars. They have more particular wants. Noisy, temperamental, in constant transit from island to sea to island to sea. It is early for them to nest but they are considering it, examining each and every possible location and what will work and what will not. Conflict is the predictable consequence with space at such a premium. Two get into a flipper fight slapping each other in a way that does no damage but probably stings. No doubt enough to get the point across. While the crabeaters ignore all of it. They simply remain in place. Silent. Neither stretching nor shifting their bulk nor arching their bodies as seals sometimes do to adjust their contact with the ice. Which means the crabeaters are neither cold nor hot. Are neither hungry nor overfull. If life is tough, they aren’t telling. Or if it is easy, and good. Their point is to be there. And they already are. But just as easily their place could be... somewhere... Else.

BASCOMB: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Mark Seth Lender’s website

- About Destination Wildlife

[MUSIC: Joshua Redman “Silly Little Love Song” on RoundAgain 9feat. Brad Mehldau, Christian McBride, Brian Blade), Nonesuch Records Inc.]

BASCOMB: Coming up – A chat with a wildlife rehabilitator about raising a wild blue jay in her home. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Charlie Haden Quartet, “Hello My Lovely” by Charlie Haden Quartet West, The Best of Quartet West, Universal Music Jazz France]

Saving Jemima: Life and Love with a Hard-Luck Blue Jay

Julie Zickefoose with Jemima, a wild blue jay she raised. (Photo: Courtesy of Julie Zickefoose and HMH Publishing)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Julie Zickefoose is an author, illustrator, and wildlife rehabilitator. She has raised dozens of different species of injured or abandoned songbirds at her home at the Indigo Hill Wildlife Sanctuary in rural Ohio. In her latest book ‘Saving Jemima: Life and Love with a Hard-Luck Jay’ she chronicles the challenges of raising a wild bird for release and what she learned from sharing her home with a wild Blue Jay. I caught up with Julie Zickefoose as part of our Good Reads on Earth series. Julie, welcome to Living on Earth!

ZICKEFOOSE: Thank you. What a thrill to be with you.

BASCOMB: Oh, we're so happy to have you. Now you own an 80 acre wildlife sanctuary in Ohio. I'm sure there are countless species there to observe. But you invest your energy and your artistry in birds. Why birds, and how did you end up with this life where you literally have wild birds flying across your living room or perched on your lampshades?

ZICKEFOOSE: Well, I've been doing wildlife rehab with songbirds in some form since I was very, very small. I grew up in Richmond, Virginia, and my next door neighbor had 17 free roaming cats. And so I was finding broken and orphaned baby birds all the time and I couldn't walk by you know, I had to help them. In my first bit of activism as a child, I convinced her to get them all spayed and neutered, and keep them indoors. At the age of eight. I had her convinced with that, so that's what started it. And then I have been doing rehab as a federal and state licensed rehabber since about 1981.

BASCOMB: And how did this one bird a blue jay, you named Jemima end up in your care?

ZICKEFOOSE: That was the magic of Facebook. I can often reroute calls, I answer the phone a lot, and to tell people what to do with things they've found. But this one was only about 10 miles away from me. And it was a blue jay. And the woman sent me a picture of it on Facebook, and I thought, Oh, I'm doomed. So I had to I had to try it because I'd never raised a corvid before, and that was one of my life goals was to raise a corvid.

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. And as you describe it, she really became like part of your family. I mean, she pestered your dog and she developed a really special bond with your daughter. Can you describe some of those relationships that developed?

The cover of Saving Jemima: Life and Love with a Hard-Luck Jay. (Photo: Courtesy of Julie Zickefoose and HMH Publishing)

ZICKEFOOSE: Yes, well, I should preface this by saying that wildlife rehabilitators do everything they can not to turn birds into pets. And that was certainly not my goal here. I have right now a song sparrow in a fledging tent in my garage, and that bird is fed and left alone. That's how you're supposed to do it. The problem with a corvid is that they are extremely social, and without social interaction with something or someone they languish and Jemima wouldn't eat unless we were around. So she grew up in the house unlike all the other birds that I raised. So it was a quite a different situation. It was us we were her family, however imperfect and big and lumpy and non feathered and, and it worked out actually really well. She had a wonderful relationship with my daughter. My daughter was the source of music. And the this bird really enjoyed music and she would pick my daughter's iPhone, asking for another tune. It's pretty crazy and my son Liam is an artist and she would sit with him as he drew and sort through his pencils and markers and carry some of them off sometimes. So we each had a different relationship with her.

BASCOMB: And she had a specific song that she would request or that she would sing with your daughter, right?

ZICKEFOOSE: Yes, yes, it was Barcelona by Ed Sheeran. And that was just a song that got her going. She liked the beat. And when the crescendo came she'd flap her wings and screech, really.

BASCOMB: And so how did you avoid the problem of imprinting? I mean, as you said, your your goal was to release Jemima into the wild. You didn't want her thinking that she was the person?

Jemima at 16 days old, four days after she was found outside the nest. (Photo: Courtesy of Julie Zickefoose)

ZICKEFOOSE: Exactly. Yes. Well, one of the neat things that happens in bird development is that early on, they hear even in the egg, they hear the voices of their parents, and they imprint on those voices and those voices are encoded in their DNA. So that's what makes sense to them is those sounds. So what I did was as we were raising her, I kept her in the kitchen, and I kept the windows cranked open. So through the screen, she could hear the Blue Jays that were coming in to the peanuts, I put on the deck railing. She could also see them and she was raptly attentive anytime there were blue jays present. So I knew she knew she was a jay. And it was very important to maintain visual and auditory contact with blue jays, I think. But the truth is, is that these birds come to us knowing who they are. And it's our job as rehabbers to release them on time. And in a blue jay that is right around day 38 to day 40. That's when they start picking up all their own food, and they're able to feed themselves with subsidy. And that's when their social bonds begin to form. So you've got to let them go in time. You can't hold on to them too long.

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. Well, tell me about some of the challenges of having a wild bird flying around your home. I mean, It's not everyday that people do that.

ZICKEFOOSE: Yeah, it is very challenging, and especially a blue jay because they mess with everything. And they steal things and they hide things and they cache food like watermelon in your couch cushions. So you don't want that. And so what we did was we would do timeouts when she was just driving us all nuts and pestering the dog unmercifully, we would time her out and take her out to the garage and put her in the tent and just say we can't do this anymore. And so after she was released, we spent a great deal of time outdoors with her to sort of transition her, but it was really seamless. She went right back, and she had bonded with a wild blue jay by mid-August, and we released her in June. So that was really neat to see.

Jemima explores her world on Indigo Hill. (Photo: Courtesy of Julie Zickefoose)

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. And so as you mentioned, you did successfully release her into the wild, but it wasn't exactly smooth sailing. What happened with her once you did release her?

ZICKEFOOSE: Yeah, well, the whole reason I had her is that she was on the ground and sick when she was found and she had been left all day, I am of the belief that birds will kick babies out of the nest that are not quite right. I once tried to raise a carolina wren that was the last to fledge from its nest and the parents had left it behind. And I found out when I set into raising it, that it had a tremor, and which was then diagnosed as a brain tumor. So it was heartbreaking. But the parents know. The parents just know when a bird is not right. So I think what had happened is she was ill, the parents knew that they were like, not going to waste any time on this one. And so she came to me sick, and I didn't know it until the illness blossomed after her release with the stress of release and being out in the wild. So then I was faced with having to medicate a free flying wild bird, which was very interesting.

BASCOMB: And how did you do that?

ZICKEFOOSE: I did that by training her to come into food and water dishes. And so I medicated her water, I sweetened with stevia so she wouldn't taste the bitterness. And then I also medicated her food. And we kept that bond going and I kept her coming in for food and water many times a day. And I kept that up for three unbelievably stressful weeks where she's flying free and I'm just hoping that she keeps coming in.

Not all of us are lucky enough to have a live-in personal chef, but Jemima was. (Photo: Courtesy of Julie Zickefoose)

BASCOMB: So, yeah, now you have rehabilitated more than a dozen different species of birds but from what I understand corvids, the family that includes crows and ravens, blue jays, like Jemima, they're more intelligent than your average bird. Does that ring true to you after living with both a blue jay and all of these different types of birds?

ZICKEFOOSE: Oh, yes, absolutely. I've actually rehabbed about 25 different species of songbirds. And it's striking how much more involved it is to raise a corvid because they are so intelligent and so needy of social interaction. So and that's what makes them fun. You know, that's what makes them really a wild ride to raise.

BASCOMB: Blue jays don't have the best reputation even among birders. They're sort of loud, they're territorial, I think they're sort of seen as the bully on the playground at the bird feeder in the yard. How do you respond to that kind of sentiment?

Jemima formed a strong bond with Julie and her family, but still retained her identity as a wild blue jay. (Photo: Bill Thompson III., courtesy of Julie Zickefoose)

ZICKEFOOSE: Well, I, I just think it's, it's ridiculous actually. Because I mean, I mean, I know people in my part of Southeast Ohio who actually shoot them off their feeders, illegally, you know, a lot of people think, "Oh, well, they're pigs, they're hogs." They come in. And what they're doing is they fill their gular pouches, their throat area with seed, and then they go and cache it, they hide it in a bunch of different places. But what's kind of neat about that is that they're often feeding small rodents, they're feeding other birds who watch them cache, you know, so it's not necessarily just that they're pigging all the seed. So I think they're maligned unfairly.

BASCOMB: And surely some of those seeds they're caching if they're the right type will grow up into trees and support the habitat.

ZICKEFOOSE: The oak forest grows through the forgetfulness of blue jays. Yes.

BASCOMB: That's a nice sentiment.

Blue Jays serve as the alarm call of the neighborhood, often the first to alert other birds to the presence of a dangerous predator. (Photo: Dave Doe, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

ZICKEFOOSE: Yes.

BASCOMB: And you write that in several instances, Jemima would actually sing I think a lot of people maybe don't know that blue jays and other corvids actually have songs. Can you describe her songs for us?

ZICKEFOOSE: Beautiful, beautiful little whisper songs and quite typical of her own species. They were perfect actually they sounded just like a wild blue jay's whisper songs but it's a sort of a sort of a sotto voce burbling series of squeals clacks clicks, whistles, little flourishes and trills and it's quite surprising actually, that something like that can come out of a blue jay. It's a lovely, lovely sound. I have recorded wild blue jays they will do imitations of other birds. And actually, this spring, I witnessed something that was one of the most remarkable things I've ever heard. There are crows in our area that attack hawks, and they make a certain you know, call when they're attacking the hawk. It's kind of a, kind of a strange little call. And this blue jay was sitting in the top of a birch tree in my yard in March. And it started off with the scream of a red-shouldered hawk, which blue jays are known to do. They imitate hawk calls. So it went: Kiyaah, kiyaah, and then it went caw caw caw, rrrrik rrrrik rrrrik, kiyah, kiyah. So it did the entire litany of the attack. It did. Here's a red-shouldered hawk. Uh oh, here comes some crows. They're calling, now they're diving on it. And then the hawk screams again.

BASCOMB: Wow.

ZICKEFOOSE: And it was just, to me it was like a performance piece. And it was surprising to me, but I shouldn't have been surprised because this is a wonderful brain that's operating here.

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. And how did you feel the day you let Jemima go?

ZICKEFOOSE: I felt exultant. It was wonderful. She was so smart about it. She stayed put in the same japanese maple tree all that day, and made only very brief forays out from it. She ate from her bowls and drank from her water and it just went really well it was the smoothest release. I've ever had.

BASCOMB Well, wildlife rehabilitators like yourself all over the country are doing this wonderful work to save individual birds. But where does that fit, do you think, in the larger context of conservation? From what I understand bird populations as a whole, are really in a crisis. The number of birds in the US and Canada is down by nearly 30% in the last 50 years.

ZICKEFOOSE: Yeah, well, I think rehabbers have a great job to do in educating the public. When I was doing a lot of songbird rehabilitation in Connecticut, 90% of the birds I took in had been injured by cats and any rehabber will tell you that that's the most heartbreaking thing that we face is that people allow their cats to roam free. That said, I do think that strides have been taken. I think that people are starting to wake up about free-roaming cats and birds. They're starting to wake up about buildings: All new constructions in New York City are now going to have to have bird safe glass. So we're out there, you know, educating people about this, and I have friends who are in Cleveland getting them to turn out the lights during migration. It's a wonderful, wonderful thing. So rehabbers have a tremendous job to do in keeping the public educated. That said, I think on a population level, wildlife rehab is really for people. I don't think that we make much more than a drop in the bucket unless you're talking about a really rare species. But the difference we make is in the hearts and minds of the people who bring these birds in, and who then follow their story and who then are more likely to stop to help the next time. So the thing to do is to be kind to everyone who comes to you with a baby bird question and this time of year with 5000 Facebook friends, that's all I get, is baby bird questions.

The bright blue of a blue jay’s tail comes from a surprising source: black pigment arranged in specific microscopic patterns which bend light waves to reflect blue wavelengths. (Photo: Dennis Murphy, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Now over the course of your time with Jemima, you spent countless hours as you've described, feeding, observing, you had to consult with veterinarians when she got sick. You took photos of her. What do you feel that you learned as a scientist, as an ornithologist from that experience?

ZICKEFOOSE: Oh my goodness, I think the thing that really floats to the top for me is that I gained an even greater respect for the things that birds come programmed with, the things that they already know, the self identity that is so strong in their makeup, even when they're tiny and featherless. They already know they're blue jays. And they do everything they can to get with their own kind, no matter how strange and artificial their upbringing, so the bird knows what it should be and how it should act. And it's our job when we're caring for them to listen to that little voice that is telling you, here's what I need, and you need to rise to that and follow your instincts to do that. I learned a lot about myself. I learned about you know, how deep is my passion for birds, and how cleansing it is and how it's my salvation really, nature is, I can, there's very little that can't be fixed with a five mile run, you know, It's out in out in nature and it's I was you know, these are these are tough times. And I think that if you can't walk out your door and get to nature, get in your car and drive to it, just get yourself out it will fix you.

BASCOMB: Julie Zickefoose is author of the book Saving Jemima: Life and Love with a Hard Luck Jay. Julie, thank you so much for sharing Jemima's story with us.

ZICKEFOOSE: Thank you Bobby. This has been a great honor.

Related links:

- Click here to learn about the blue jay’s “whisper song”

- Read more on Julie’s popular natural history blog, and see a video of Jemima singing

- Click here to take a peek at the book

[MUSIC: Billy Novick/Bob Nieske Duo, “Alone Together”]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Anne Flaherty, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Kori Suzuki, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to Destination Wildlife. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts. We tweet from @livingonearth. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth