Systemic Racism and Green Groups

Air Date: Week of July 31, 2020

Many in the environmental movement remember John Muir, the founder of the Sierra Club, as a philosopher, a leader and a protector of places like Yosemite Valley, but with strong views of white supremacy. (Photo: Jim Bahn, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

The environmental movement in America has deep ties to the nation’s history of systemic racism and white supremacy. Now, as Americans confront racial injustice anew, powerful green groups like the Sierra Club are beginning to reckon with their own histories of hate and exclusion. Washington Post Environment Reporter Darryl Fears joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss this moment of reflection within the environmental movement.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Like many other aspects of this country, the environmental movement has deep ties to America’s history of racism and white supremacy. Issues like pollution and climate change, even the Corona Virus, continue to take the greatest toll on Black and brown communities. And core environmental ideas like “wilderness” ignore the theft of land from Indigenous tribes. Today, the national environmental movement is dominated by white voices and often excludes people of color. Environmental justice is more local snd frequently an afterthought in green agendas. But now, as the United States confronts a history of racial injustice, powerful environmental groups like the Sierra Club are reckoning with their own history of racism. Darryl Fears covers the environment for The Washington Post, and he joins me now to discuss this moment of reflection within the environmental community. Darryl, welcome back to Living on Earth.

FEARS: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So, tell me about this announcement that the Sierra Club's executive director Michael Brune made about race in his organization recently.

FEARS: Michael Brune looked at the Black Lives Matter protests, and it was a reckoning for him and the leadership of the Sierra Club. And as a result of it, the Sierra Club made a general announcement that it was aligning itself with Black Lives Matter to say that Black lives indeed matter. And then he took it a step further, and said, not only do we recognize that Black lives matter, and this racial reckoning needs to happen in the United States, but we're going to look at the past of the Sierra Club, which was fraught with racial history, and at its founder, John Muir, who said some pretty disparaging things about people of color, including African Americans and American Indians.

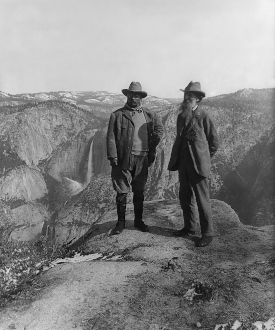

CURWOOD: I think most people know a little bit about John Muir, Darryl. Many in the environmental movement, remember him as the philosopher, the explorer, the protector of places like Yosemite. Tell me a little bit about who john Muir was and how he came to found the Sierra Club.

FEARS: John Muir is of Irish descent. And he was a fairly simple man, a philosopher who love nature. He lived in California. And there, John Muir is a giant. He's called the patron saint of the wilderness. He's called the father of national parks, because he fought to preserve vast areas of land, of course, including Yosemite, what is now Sequoia National Park. He famously as a boy walked from the Midwest to the Gulf of Mexico, a kind of pilgrimage and wrote of his travels. John Muir is a legend, and particularly for the Sierra Club.

CURWOOD: So he loved the wilderness. But as the National Park System is getting put together, this is when formerly enslaved African Americans are running into the world of Jim Crow. And the US government is driving Indigenous people off the lands. How did John Muir fit into this historical moment?

Black Lives Matter supporters march on June 13, 2020, just two weeks after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. (Photo: Geoff Livingston, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

FEARS: He didn't look upon Black people respectfully. I mentioned that walk from the Midwest to the Gulf of Mexico, which would have taken him through Louisiana. And on his path through the South, he encountered African Americans who were sharecroppers and people who were just one step removed from slavery. And he said at one point that the black people he encountered were a merry bunch that pretty much kidded around all the time, and did very little work. And he said, a white man with determination and will could pick as much cotton as six Sambos and Sallies. And for your listeners, Sambos and Sallies, "ie-s," are pejoratives that are right up there with the N-word. He said of American Indians that their culture was dirty, that they were filthy and uncivilized and could largely be dismissed as a people.

CURWOOD: Of course, John Muir goes on to found the Sierra Club, one of the nation's oldest and most prestigious environmental organizations. What does this mean for the environmental movement to have some of its foundational moments and leaders rooted deeply in notions of racism and white supremacy?

FEARS: I think the same thing that it means for the country at large. The founding fathers were the same types of people. I think that what's different is that we don't learn about the white supremacist roots of conservation groups at all in school. We don't learn much about the founding fathers in school, but we don't learn anything about the supremacist roots of these groups. And it's interesting that now, 20 years into the new millennium, they feel a need to come clean about these roots when they've existed for a very long time. You're talking about Madison Grant who wrote the passing of The Great Race or the racist basis of European history that Adolf Hitler, before he became the leader of Nazi Germany, called his Bible, and Joseph Leconte and David Starr, people who believe that eugenics and who believe that inferior people should not be allowed to breed they should be sterilized for the preservation of whiteness so that there will always be more white people than people who are non-white in the United States. It's interesting that they feel compelled to come clean and talk about this now.

President Theodore Roosevelt (left) and environmental philosopher and Sierra Club founder John Muir (right) both advocated for racial exclusion. (Photo: GOGA Park Archives, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And Darryl, by the way, how fair is it to say that, at a local level, there are many Black people involved in environmental advocacy? The whiteness is most obvious at the national level?

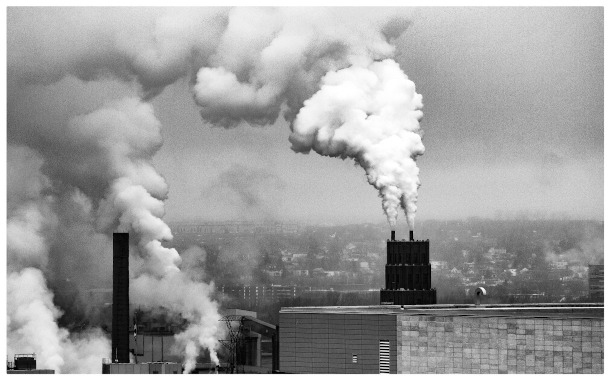

FEARS: Yes, generally, when African Americans and Latinos and Native Americans are involved in this movement, they separate themselves into another category, which is the environmental justice movement. The environmental justice movement pretty much exploded into being in 1991 when Warren County, North Carolina fought this massive waste dump in this community and lost, in the judgment of environmental justice activists, very unfairly. And so in 1991, they circulated a letter and said let's meet in Washington. At that meeting in Washington, they began to call themselves environmental justice advocates and activists and they formed an organization and they move forward. And these groups work in the shadow of the big green groups. And in the shadows, obviously, of the foundations that give money to these green groups. They work in impoverished communities and they work in poverty themselves, they are barely funded, and they do the work required to keep power plants that pollute the air away from these people or to keep them honest, as much as they can.

CURWOOD: The people of color environmental movement. So Michael Brune in his essay discussing this referred to pulling down our monuments and starting with some truth telling about the club's early history. As we've seen with the Confederate battle flag, and the statues of folks from Robert E. Lee, Fort Bragg named after Of course Braxton Bragg, a notably unsuccessful Confederate general, there's a lot of pushback when these things are postulated. How successful do you think Michael Brune is being in this quest?

FEARS: It's hard to know. I mean, his quest is only a few weeks old at this point. It's interesting because the Sierra Club has numerous chapters. It has quite a few in the state of California and about one each in every other state. I think that, when Michael Brune began to draft his essay, or his blog posts are calling for almost a repudiation of some of the sayings of John Muir, he worried greatly about what the chapters in the south would say. Places like Louisiana, and Texas and Georgia, with all these chapters and all these chapters are very important to the Sierra Club. There is talk about whether this is fair, whether you should repudiate someone who was just doing what was normal at the time. I've received a number of emails saying that these groups shouldn't change at all. But those were a minority. I received quite a few emails from members of the Sierra Club saying that it's about time that we took this step. And so it'll be interesting to see how this affects the organization moving forward, because I don't think that we've seen the end of this issue.

Big green groups like the Sierra Club built their reputations on fighting to protect wilderness and nature, but have a mixed record of helping communities of color disproportionately impacted by pollution or climate change (Photo: Lida, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So Darryl, as the Sierra Club is finally confronting its racist history. There's also another reckoning going on in the big environmental groups like the Union of Concerned Scientists about diversity and inclusion, right? Can you tell me what's going on there?

FEARS: Right, the Union of Concerned Scientists made a commitment like the many of the other groups about 10 years ago, to be more inclusive in its organization and recruit more people of color onto its staff. And one of those people that recruited just three years ago is a woman named Ruth Tyson and Ruth Tyson--she's a Jamaican immigrant who came to this country when her mom was seven months pregnant with her--had been working in the environment which doesn't pay well, she was working three jobs and a friend handed her an ad about a $47,000-a-year job at the Union of Concerned Scientists and she jumped on it because she said it was more money than her parents had seen and more money that she had seen in a year. Ruth says that she gets to the Union of Concerned Scientists, and there is no real infrastructure there to support either her or her work as a person who reaches out to non-white communities. And there are few African Americans there as well. And so there is almost no camaraderie. And she describes the white people or her co-workers, her white coworkers, as fairly cold and not very communicative with her. Her work is criticized. Her ideas are dismissed. Three black women who were on her team were forced out or quit because of the treatment they received. And Ruth also noticed that every time there was some attempt to reach out to African American communities, she was recruited almost as the voice of those communities. And three years later, she finds herself very frustrated, and she's on the verge of quitting. And before she quits, she decides to write an email explaining why she's quitting the organization with only three days notice. And she starts to write the email. And three days later, the email has become 17 pages, a manifesto of searing criticism about what she encountered there. The work she was hired to do was kind of an afterthought as a result of an organization that says, Okay, well maybe we should be more inclusive and hire some black and brown people. And she felt that it was time for her to go.

Environmental issues like pollution and climate change have a hugely disproportionate effect on Black, Brown and Indigenous communities. (Photo: Andre Turcott, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Darryl by the way, how has the Union of Concerned Scientists responded since you wrote about her experience in your story?

FEARS: That was the most fascinating thing of all, because I read the manifesto 17 pages long, very long. And I thought, wow, I'm sure the Union of Concerned Scientists will say that some of this is unfair. And so I called the president of the organization and was told that he agreed with all of it. And I said, "All 17 pages?", and he said, "Yes." And in addition to that, he said he was very concerned and heartbroken that she found her treatment at the organization so unfair. And I thought that was remarkable. In fact, just as a journalist who's used to tension in these interviews and a give and take, I was kind of thrown off balance by his total agreement with her. And then I started interviewing the leaders of other organizations. Because the letter circulated everywhere. Ruth Tyson sent the letter to 200 people at the Union of Concerned Scientists, who then sent it on to basically the entire conservation field. And when I talked to the leaders at organizations, they had not only read it, but they too agreed. They said that her words rang true of what they've been told by the non white staffs at their organizations. And Michael Brune said that he found it heartbreaking, and that it aligned with the criticism that he heard at the Sierra Club.

CURWOOD: So demographically in another 20 years, majority of people in this country are going to be people of color. Already the majority of schoolchildren are people of color. So to what extent are the white dominated green groups facing, frankly, a reduction of impact given the demographic changes in this country?

FEARS: I think that's just it. I think if they don't diversify, they're really not representing everyone. They're really not representing the people they say they represent. As it stands, people of color represent 40, 41% of the population of the United States. In 2050, only 30 years from now, people of color will be a majority in the United States. And so green groups would have to change, a great deal to represent a majority of the people in the United States over those 30 years and once again, over the last 10 years, they've done a very poor job of changing themselves to do that.

A Field Medic with the Oceti Sakowin Camp of Water Protectors raises her right fist near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota. (Photo: Avery White, Oceti Sakowin Camp, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So then what comes next? These are organizations that are fighting high stakes issues, climate disruption, the loss of tropical forest that among other things, got us into this COVID pandemic problem, pollution, public health, which by the way, disproportionately affects Black, brown and Indigenous peoples much more than white people in this country. So they agree that they haven't been doing the right thing. The problems are huge. What are they going to do now in response?

FEARS: You've touched on it. These groups do great work, they do the work to protect the environment, they do try and serve their mission as best they can. But at the same time, these groups have felt that they haven't really reached out to Black and brown communities the way they should for at least a decade, and the decades since acknowledging that, they've done very little. I think that they've always known where they fit in. I think that they were comfortable with the general public not knowing and the history was largely hidden. And I think around the last time that I was on your show, I wrote an article about the lack of diversity in these groups because I had been reporting on environmental issues for about four years and everywhere I went, there were hardly any other people but white people in the room and it was stark. And after three years reporting. I asked, why is that? White people aren't the only people who are impacted by pollution and climate. And white people aren't the only people who care about the environment. And so I started really probing this question. And I started talking to the groups and I wrote a story about the lack of diversity therein and in writing that story, that's when I personally began to learn about the history. I already knew about Teddy Roosevelt. But I didn't know about John Muir's connection to white supremacy and white supremacists. And I didn't know about Madison Grant, and others. And that began my education about the origin of these groups. And so we can't really trust that they'll transform themselves 10 years from now. As a journalist, I'm just going to have to really follow them to see if they do evolve into the groups they say that they're going to evolve into. Meanwhile, the environmental justice movement is saying, look, we're gonna call on the foundations that give them money to give money to us because we are more concerned about our communities. We don't have to worry about diversifying our groups, we can do this work. We don't have to rely on these green groups to do this work. It's not just the green groups. It's the foundations that fund them. And it's whether people begin to trust the ability of groups with direct connections and direct concerns for the communities that green groups say that they're now going to represent. Perhaps environmental justice movements can do the work better than these green groups.

A Sierra Club postcard depicts an endangered bald eagle in flight. (Stephanie, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Darryl Fears covers the environment for The Washington Post. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

FEARS: Thank you. I hope I answered all your questions.

NOTE & CORRECTION: The guest erroneously stated that John Muir was Irish. John Muir was born in Scotland and emigrated to the United States with his family at the age of eleven.

Links

Ruth Tyson | “An Open Letter to UCS: On Black Death, Black Silencing, and Black Fugitivity”

Los Angeles Times | “Sierra Club Calls Out the Racism of John Muir”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth