July 31, 2020

Air Date: July 31, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Saving Forests Could Save Us from Diseases

View the page for this story

COVID-19 is just one in a line of numerous diseases that have spilled over from animals to the human population, often thanks to deforestation and the wildlife trade bringing infected wildlife close to humans. With the COVID-19 pandemic alone estimated to cost several trillions of U.S. dollars, a new study suggests that spending just a tiny fraction of that to curb deforestation and the wildlife trade could prevent another costly pandemic. Coauthor Aaron Bernstein MD of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health joins Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb to talk about the costs and benefits of preventing future so-called zoonotic disease outbreaks. (14:48)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News weekend editor Peter Dykstra talks with Host Steve Curwood about how Costa Rica brought its forests back to life with aggressive measures to protect public lands, and incentives for landowners to convert from logging to participating in ecotourism. They also discuss how California is urging Uber, Lyft, and other rideshare companies to significantly decrease greenhouse gas emissions by transitioning to mostly electric cars by 2030. In environmental history, Peter explains McDonalds’ 1990 agreement with the Environmental Defense Fund to stop using Styrofoam packaging for its burgers. (05:20)

Race and the Nature Gap

View the page for this story

Americans of color experience nature deprivation at three times the rate of white Americans, according to a new report from the Center for American Progress. Jenny Rowland-Shea is lead author of the report and talks with Host Steve Curwood about how systemic racism has limited access to nature for Black Americans in particular, and how conservation and sensitive planning can help narrow the nature gap. (08:28)

Parktracks: Sounds of the Kiowa Nation Buffalo Songs

View the page for this story

The Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division of the National Park Service has compiled hundreds of sounds from parks all over the country. In this recording, members of the Kiowa Nation of the southern Great Plains sing traditional Buffalo Songs. (01:35)

Systemic Racism and Green Groups

View the page for this story

The environmental movement in America has deep ties to the nation’s history of systemic racism and white supremacy. Now, as Americans confront racial injustice anew, powerful green groups like the Sierra Club are beginning to reckon with their own histories of hate and exclusion. Washington Post Environment Reporter Darryl Fears joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss this moment of reflection within the environmental movement. (17:43)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Ari Bernstein, Darryl Fears, Jenny Rowland-Shea

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Data show that Americans of color are nature-deprived at three times the rate of white Americans.

ROWLAND-SHEA: We hope that this report helps the public understand that disparities across racial and economic groups are a result of systemic inequalities and environmental racism, including practices like redlining, prioritizing parks in white neighborhoods, siting factories and energy projects in communities of color.

CURWOOD: Also Sierra Club president Michael Brune on the group’s racist past.

FEARS: Then he took it a step further and said, not only do we recognize that Black lives matter and this racial reckoning needs to happen in the United States, but we're going to look at the past of the Sierra Club, which was fraught with racial history.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Saving Forests Could Save Us from Diseases

Preventing deforestation is a crucial step in the fight to prevent outbreaks of diseases humans can catch from wildlife. (Photo: Kate Evans, CIFOR, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Many human diseases actually originate in animals. Think of HIV, malaria, Lyme disease and of course Covid19, scientists call them zoonotic disease. This Coronavirus got its start in the wet markets of Wuhan, China, likely from a bat or pangolin being sold there. More than 660,000 people have died from Covid19 costing trillions of dollars worldwide and we’re still not out of the woods but the answer to preventing future outbreaks may very well lie in the woods. Forests are the source of animals that can carry these diseases. A new study published in Science suggests we could avoid the next pandemic and save trillions of dollars by spending tiny fraction of that to curb deforestation and the wildlife trade. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb is here now. Hi Bobby, now you spoke with one of the co-authors of the report, right?

BASCOMB: Hi Steve, yes, I spoke with Dr. Ari Bernstein he is a pediatrician with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. And I started my conversation with Dr. Bernstein by asking him about zoonotic diseases that move from animals to people.

BERNSTEIN: We see the emergence of new diseases, the appearance of new diseases like COVID, overwhelmingly coming from wild animals and to a lesser extent, domesticated animals. And that reflects increasing contact between people and wildlife in particular. And of course, the reality that we live in a highly connected world, with many densely populated cities, that those two things together really amplify. When a disease moves into a person, the chances that it spreads to lots of other people are much higher.

BASCOMB: And zoonotic diseases are actually very common. I've read that something like six out of 10 diseases in humans actually originate in animals. Can you give us some examples that people are familiar with?

BERNSTEIN: Sure, the reality is that we swim in a common germ pool with all other animals. And so there are some diseases like COVID-19 that have come directly from an animal to person. There are other diseases which you know, are in people, but they're sort of a first cousin in other species. A good example of that is something like chicken pox. There are similar viruses. There's monkey pox, there's camel pox. And you can actually have some transmission of those other pox virus into people, but these viruses shared a common ancestor. And of the diseases that people commonly get, you know, there are lots of these zoonotic diseases. You know, there's plenty of examples around the world, whether it's rabies, or Lyme disease, West Nile virus in the United States. And so it's really more the rule, as you point out, than the exception. And so we shouldn't be terribly surprised that when we're changing life on Earth at such a rapid rate today, that we're sort of stirring the pot of the common germ pool, so to speak, and that these diseases, particularly viruses, tend to pop out into people.

BASCOMB: And in your paper, you list several ways to help prevent future zoonotic outbreaks like COVID-19. What are some of those suggestions?

COVID-19 is believed to have started in one of China’s wet markets, likely through consumption of a bat or pangolin. (Photo: Whiz-Ka, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BERNSTEIN: You know, the paper came about because a group of folks were bewildered by how much was being spent to deal with one emerging zoonotic virus. And the question was, well, how much would we have to spend to do what we know we need to do to prevent these viruses from spilling over into people. A good chunk of these emerging diseases come from deforestation, and not necessarily the cutting down of trees, per se, but all the activities that come with that. So building of roads, the establishment of settlements in forests, the likelihood that people are going into the forest, not just to chop down trees, but perhaps to gather wildlife. And so we looked at how much it would cost to reduce deforestation in places that are particularly high risk. We know another chunk of emerging infections come from wildlife trade, we see this with, you know, the pet trade, where people import pets from various corners of the Earth and the places and the pets are carrying pathogens. The part of the wildlife trade that we were most concerned with is actually not at the buyer end, it's at the procurer end. It's that there are people who are going out into wilderness and harvesting animals, for pets, for medicines, for furs, for all kinds of stuff. And those contexts are the high risk ones. And we know that because what little work we've done to understand what viruses in particular may be in wildlife shows that there are lots of viruses. And in the case of, for example, coronaviruses like SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, or the past SARS virus, their natural host is bats and you look in bats, there are lots of coronaviruses in bats. And so as people go into the wilderness, you know, bats are often captured as food, but they're also captured for other reasons. So we focus on what it would take to really address the risks. And the third big area we try and tackle is surveillance. So you know, it's not, I think practical to stop the wildlife trade, it's not going to, we think it's impractical to end all tropical deforestation, as much as I think many people would like to see that. So what we need to do is we need to have much better surveillance of wildlife and people who are at high risk for spillover. And so we try and think through which organizations and what the budget would be to do that, and those are the three big areas.

BASCOMB: So really, what you're calling for then is to limit the human wildlife interaction. What evidence is there that any of these methods, though, that you suggested would actually help prevent the spread of disease?

Deforestation and the side ventures that go along with it, such as roadbuilding and logging, increase the likelihood of animal contact resulting in zoonotic disease spillover. (Photo: Jan van der Ploeg, CIFOR, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BERNSTEIN: What we have at this point is proof of concept. So there have been very small scale interventions along the lines we described that have definitely prevented us spillover. A good example of this is Nipah virus in Bangladesh. Nipah virus first emerged in Malaysia in the 90s. And there have been subsequent outbreaks in Bangladesh. And in Bangladesh, the virus is transmitted from bats to people, it turns out through date palm sap. In Bangladesh, palm trees are tapped like maple trees are tapped here in New England for their sap, and there are buckets put on the trees. And the bats like the syrup, so they would defecate into the palm sap. And a very easy way of dealing with that is by covering the buckets. That's a pretty low-cost, low-tech, highly-effective way to prevent spillover. There is also the PREDICT program, which has been much in the news. That was a 10 year program funded by the United States Agency for International Development that works to do viral discovery in bats. It is the reason why we know what we know about the prevalence of coronaviruses in bats in Asia. And looking into those viruses, it gives us a sense of what may be out there. Now, we don't know whether any of those viruses are going to be big problems for people. We don't have the science to know that yet. But it is certainly helpful. And you know, there's a proposal to do that at a much bigger scale called the Global Virome Project that would seek to identify 70% of the viruses that are in wildlife in high-risk areas. And then of course, with the wildlife trade, we've seen bits and pieces of this. I think one of the challenges of the wildlife trade is there's really no entity in the world that's charged with monitoring wildlife for diseases. There's also by the way, work on deforestation showing that protecting forests protects outbreaks, certainly with vector borne diseases, and also other diseases that may come in the forest like Ebola. So we're really calling for a scaling up of this. And we've talked about in this paper how important it is to really do good science around the efficacy of these interventions as they scale up.

BASCOMB: And obviously if we were able to dramatically reduce deforestation and the wildlife trade, that would have many other knockoff benefits as well. You know, tropical forests, of course, are a crucial carbon sink, and it would protect biodiversity, which is in crisis. Can you tell me more about that, please, if you've looked into it?

BERNSTEIN: Sure, yeah, no, it's a critical part of our argument. You know, I think many people would rightly be a bit skeptical of how effective the interventions we propose are going to be. I think we are pretty clear that while we know preventing deforestation and addressing the wildlife trade, and really doing better surveillance, carry the potential to reduce risks of spillover, we can't say with great certainty what the return on investment there is, because we haven't really done it at scale. And so we need to really understand that. But at the same time, if we have your point, which is that we have a bunch of reasons to be doing these things anyway, particularly preventing deforestation is the clearest example. You know, we not only have the carbon value that you alluded to, there's huge water value, so, particularly tropical forests are hugely important to local water resources. There's indigenous rights. But there are other things that protecting forests do, they prevent fires. And so you see, you know, compounding value that occurs when you protect forests. And now we add another dimension, which is prevention of disease spread.

It is estimated that the Covid-19 pandemic will cost the world around $6 trillion in lost GDP in 2020 alone. (Photo: Don Harder, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, how much might these strategies cost to implement? And how does that compare to the cost of dealing with the COVID pandemic to begin with?

BERNSTEIN: The COVID pandemic has cost roughly $6 trillion in lost GDP. Governments have spent huge sums of money to try and prop up economies. And on the other side of it, you can put a dollar value to the deaths that have occurred. Economists assign what's called a value of a statistical life. And you come up with a dollar figure, you multiply that by the number of people who have died, and you're talking another several trillion dollars in value there. So the cost of doing what we recommend, so that's substantially increasing the budget for addressing the wildlife trade, putting in measures to reduce deforestation by half, dealing with wildlife trade and surveillance, we estimate those costs to be somewhere around $20 to $30 billion for those. And so when you do the math, you look at $20 to $30 billion versus, you know, $6 trillion in GDP loss, and many more trillion in other expenditures. And it becomes clear that salvation comes cheaply. And even if you spent that $20 to $30 billion, every year for a decade, you'd still only be on the order of 1% to 2% of the costs of this one pandemic. And it's very easy to forget that there's nothing written that this can't happen again. And there's also nothing written that this is the worst pathogen that might spill over into people. So, you know, I think certainly as a clinician, as a doctor, if I had any capacity to prevent the kind of, you know, disease and suffering that this kind of thing did for essentially the cost difference we see here between the prevention actions we're talking about, and the cost of this one disease, I would be committing malpractice not to use it.

BASCOMB: Well, you know, that sounds like a really good investment, but a tall order, with many world economies struggling because of the pandemic. Where would this money come from, and where should it go?

Aaron Bernstein is the Interim Director of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, a pediatrician at Boston Children's Hospital, and an Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School. (Photo: Courtesy of Harvard School for Public Health)

BERNSTEIN: Part of the answer to that is easy. The money needs to come from richer countries, and it needs to come from them out of self-interest, because, you know, we can clearly see in the United States that we have a huge problem in this country from a virus that emerged somewhere else. And so we have a direct interest for our own people, for our own economy, in doing things that would prevent the spillover diseases that happen in other parts of the world. And the money would go to places that we know spillover is more likely. And I think, you know, pretty clearly, we can't afford not to do these things. I can't even imagine a situation in which another virus like a COVID emerged in the coming year. And so to not make an investment, which is a rounding error of the massive sums of money that are being spent right now to try and prop up economies, and deal with the virus that's emerged itself is crazy. We would really be foolish to not spend a few percent of the price tag of this one virus to do anything we can to prevent another pandemic like this one.

CURWOOD: Dr. Ari Bernstein, with the Harvard Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment. So, Bobby, you’ve spent a lot of time in tropical rainforests, specifically Brazil reporting on deforestation. So, what’s going on in Brazil today?

BASCOMB: Well, not only do they have one of the biggest outbreaks of Covid 19 but after years of protecting the Amazon deforestation is on the rise there again.

CURWOOD: What’s going on?

BASCOMB: Well, Jair Bolsonaro was elected president in January of 2019. He has called climate change a hoax. While much of the world see the Amazon as the lungs of the world, an international treasure, he sees it as a commodity to be exploited for Brazil’s economic gain. He favors more mining on indigenous land, which is constitutionally protected. He’s reduced the amount and number of fines imposed on people who illegally mine, farm and log in the Amazon.

CURWOOD: For years Brazil has worked with the international community to curb deforestation. How have they responded to the new president and his approach to the Amazon?

BASCOMB: Right, the Amazon fund started in 2008 and raised more than a billion dollars to help halt deforestation. The lion’s share of that money came from Norway. Norway has suspended donations and Germany had planned to donate about 39 million dollars to the fund but Mr. Bolsonaro told them to keep their money, Brazil doesn’t want it.

CURWOOD: Wow. That really leaves us in a tough spot. Brazil has the world’s largest rainforest and is so important in terms of sequestering carbon and stopping run away climate change. And now we have yet another reason to curb deforestation to prevent future outbreaks of diseases like Covid19 as Dr. Bernstein told you earlier.

BASCOMB: Yes, exactly. The idea has been to pay for the ecosystem services that rainforests provide and now we see a standing forest provides yet another service, housing the animals that can transmit deadly diseases if they come in contact with people. But Mr. Bolsonaro’s track record doesn’t suggest that he’s going to be open to that. Although, after downplaying the seriousness of Covid19 he did actually contract it himself so maybe there’s hope.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Bobby. That’s Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

NOTE & CORRECTION: Dr. Bernstein reached out to us on August 2nd with the following correction: "In the interview I said that chicken pox was a human variety of a pox virus with analogues in other animals (eg camel pox). I should have said small pox, not chicken pox. Chicken pox is a kind of herpes virus (which, for the record, are closely related to the pox viruses, and we treat these with the same medications, eg)."

Related links:

- Read “Ecology and Economics for Pandemic Prevention” in Science

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health | “Solutions for Preventing the Next Pandemic”

- Read a Q&A with Dr. Aaron Bernstein on the connections between climate change and COVID-19

- The Harvard Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment (C-CHANGE)

- About Aaron Bernstein, MD

[MUSIC: Tibetan singing bowl https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OW7TH2U4hps]

CURWOOD: Coming up – New research finds being black brown or poor likely means you have less access to nature than white people. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Mario Grigorov, “Magic Circus” on Paris to Cuba, by Mario Grigorov, Warm & Genuine Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Costa Rica successfully regrew much of its lost forest by transitioning from logging to ecotourism. (Photo: Jean-François Renaud, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. And now it's time to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia - hi there, Peter. What's going on?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. You ready for little good news amidst all the bad news we always seem to have on this beat?

CURWOOD: Oh, you better believe it. What do you got for us today?

DYKSTRA: A little story from my alma mater, cnn.com, about how Costa Rica regrew its lost forest. Costa Rica, like just about any nation in the tropics, saw heavy duty logging. In this case, it began in Costa Rica after World War II, continued into the 1970s by which time Costa Rica had lost half its forests. But in the 1980s, Óscar Arias, who later won the Nobel Peace Prize, took over as President, and under Arias, Costa Rica began an aggressive campaign to cast itself as eco-minded. They reversed the damage, supplanting the lost income of logging with income from ecotourism.

CURWOOD: So how exactly did they do this?

DYKSTRA: They did this by showing landowners that the logging money was a one time benefit, whereas ecotourism dollars would come back year after year after year. And also on federally owned lands, Costa Rica became one of the best creators and managers of national parks, both along its beautiful beaches and inland in the rainforests. And the forests have bounced back spectacularly.

CURWOOD: So, Peter, to what extent could other countries around the world emulate what Costa Rica has done?

DYKSTRA: I think other countries have to emulate the stopping of logging of their forests. They won't all see the same benefit from ecotourism because that dollar can't be sliced 100 different ways, but they will certainly get the benefit of seeing their land not turn to almost nothing when grazing land is exhausted, and the trees can't grow back quickly either.

CURWOOD: And not to mention the benefit for climate stability as well. Hey, what else do you have for us today?

To regulate greenhouse gas emissions from rideshare companies, California wants most Uber and Lyft vehicles to be electric by 2030. (Photo: noeltock, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DYKSTRA: A story from California that may also be good news. It involves regulation which some people hate, but the potentially regulated don't seem to mind. Uber and Lyft, growing in popularity, showing signs that they're not just a passing fad, they're here to stay, but they're also largely unregulated in terms of greenhouse gas emissions. Only 1% of California's vehicles for hire are estimated to be electric vehicles. California wants them to be two thirds almost of their rides from electronic vehicles in only a decade, by the year 2030.

CURWOOD: So, how's this going to happen? As I understand it, if you drive for Lyft or Uber, you have to buy your own car.

DYKSTRA: You have to buy your own car - in some cases, rent your own car. Some Uber and Lyft drivers are using rentals, they find that more cost effective, but they're hoping that in 10 years there will be enough of a market and enough profitability in electric vehicles. Lyft has already endorsed the idea. Uber says they're open to further discussions.

Lyft has agreed to the proposed regulation to limit air pollution in California, while Uber says it is open to discussion. (Photo: Stock Catalog, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Okay, Peter. It's time for us to take a look back in history. What do you see?

DYKSTRA: It's a monumental 30th anniversary. August 1, 1990 was the day that McDonald's, the world's largest purveyor of fast food, and the Environmental Defense Fund came to an agreement that among other things, would drop polystyrene packaging, those legendary clamshell boxes for burgers from their menu, and it was a major breakthrough, but McDonald's didn't completely drop all of their polystyrene Styrofoam packaging until the year 2018.

CURWOOD: So is this greenwashing, Peter? Was this more for optics or what practical effect has it had on pollution from this?

DYKSTRA: Well, can it be both? I mean, on one hand, you've got all this packaging - McDonald's legitimately reduced its waste stream to landfills, they legitimately used a better form of packaging. But, it's not like they ended taking some of that rainforest beef with its own baggage on greenhouse gas emissions, and serving it up as billions and billions of burgers every year.

CURWOOD: So, what role did consumers play in this? You mentioned the Environmental Defense Fund, but what about people in the public?

In 1990, McDonalds stopped using Styrofoam packaging for burgers after pressure from grassroots groups and the Environmental Defense Fund. It wasn’t until 2018 that McDonald’s stopped using Styrofoam packaging completely. (Photo: Stock Catalog, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: EDF, Environmental Defense Fund, were the reasonable guys that came to the table with McDonald's. But, as much as three years earlier, there was a grassroots campaign - activists like Lois Gibbs, the legendary hellraiser from the Love Canal neighborhood, who launched something called the McToxics campaign three years earlier, in 1987 to pressure McDonald's to change its packaging. One can safely say that three years worth of grassroots hellraising sort of softened the market for EDF to come in, and make the score and make the change with McDonald's.

CURWOOD: Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- CNN | “This Country Regrew Its Lost Forest. Can the World Learn from It?”

- WIRED | “California's Air Pollution Cops Are Eyeing Uber and Lyft”

- Center for Health, Environment & Justice | “McDonalds Decades Later Eliminates Foam Everywhere”

[MUSIC: Vusi Mahlasela, “Loneliness” on The Voice, by Vusi Mahlasela, ATO Records/BMG Music]

Race and the Nature Gap

People enjoy the park space of the quad at the University of Washington in Seattle. (Photo: Shunya Koide on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: One of the safer things to do during the pandemic is to get out and enjoy nature, but according to a new report it’s much tougher to do if you are black, brown or poor. Communities of color in the U.S. experience “nature deprivation”, or lack of access to nature, at an average of 3 times the rate of white communities, according a study by the Center for American Progress and the Hispanic Access Foundation. On a state by state basis the research team combined spatial data with census information on race, family structure, and income. They found that 74% of communities of color are nature-deprived, compared to only 23% of white communities. The lead author is Jenny Rowland-Shea, senior policy analyst for Public Lands at the Center for American Progress. She joins me now from Washington, D.C. – Jenny, welcome to Living on Earth!

ROWLAND-SHEA: Thank you so much for having me.

CURWOOD: Now, why is nature deprivation something that we all need to be concerned about?

ROWLAND-SHEA: Nature deprivation is important because there are a number of benefits that come along with being exposed to nature, whether that's air quality, water quality or just the ability to get outside. I think during these times of coronavirus, people have been especially needing to stretch their legs, be distant from people, be in fresh air, and that's really important.

CURWOOD: Now, Jenny, people who look like me, at the end of slavery, were supposed to get the 40 acres and a mule; that, that never happened. To what extent is nature deprivation the direct consequences of systemic racism and white supremacy in this country, do you think?

The Nature Gap report looked at the lower 48 states and Washington, D.C., pictured here, which turned out to not show a gap in access to nature based on race. The nation’s capital, which is 45% African American, has many parks throughout. (Photo: Thomas Hawk, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

ROWLAND-SHEA: Yeah, so fundamentally, we hope that this report helps the public understand that disparities across racial and economic groups can't be explained away by luck or randomness or individual choices; that the stark disparities are a result of systemic inequalities and environmental racism, including practices like redlining, prioritizing parks in white neighborhoods, siting factories and energy projects in communities of color, even paving directly through or over diverse communities. And the data that we found suggests that communities are still living in a nation that hasn't fully reckoned with that past or found a way to live up to its ideals of equity and justice. And that is certainly I think the underlying cause of why we're seeing this nature deprivation right now, even though it may not be fully obvious. Things like the dispossession of Native American land certainly is still having an impact on the kinds of resource management decisions that are happening on tribal lands and near Native American communities. So any solutions to this problem needs to be rooted in that recognition and understanding the underlying problem.

CURWOOD: You looked at nearby nature access for folks, so you weren't comparing, say, somebody who lives in Cleveland to somebody who lives in Wyoming or Montana on this basis. The problem is a nearby one, I gather.

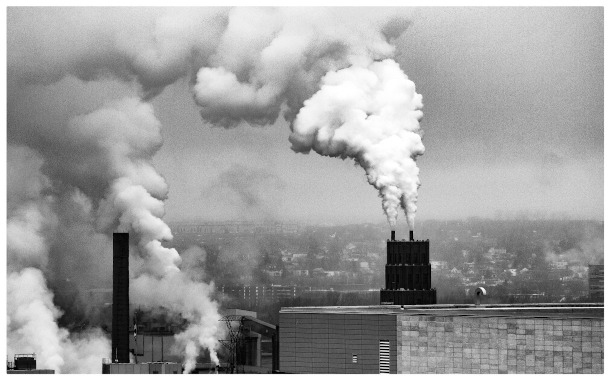

Industrial activities add to nature deprivation by hindering access to many of the key benefits of nature, including clean air, clean water, and natural sounds. (Photo: Mark Dixon, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

ROWLAND-SHEA: Exactly. Nature deprivation in the report describes places with a higher proportion of natural area lost than the state level medium. So what counts as nature deprived in a Northeastern state is not going to be the exact same as somewhere in the West, it will vary by state, but functionally, nature deprivation is describing a place that has fewer parks, streams and other natural areas nearby.

CURWOOD: So I'm sitting down Jenny, what state has the most disturbing numbers?

ROWLAND-SHEA: So a lot of the Northeast has some pretty disturbing numbers in Connecticut, we're seeing that only 10% of white communities are nature deprived, where we're seeing 93% of communities of color; in New York, it's only 9% of white communities and 87% of communities of color being nature deprived. In Vermont 76% of communities of color, compared to just 27% of white communities are nature deprived. I think it has to do primarily with them being states with high populations of white people. And so where the data is coming up as census tracts that are counting as majority minority are going to be mostly in urban areas. And so that's where those numbers are coming from, I think. But the question is, really, how do you make sure that everyone, including people living in cities, have access to nature and its benefits?

Green space and cityscape mix in Austin, Texas. (Photo: Carlos Alfonso on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: And what are the other key findings that you came to?

ROWLAND-SHEA: We also found that low-income communities are about 20% more likely to live in nature deprived areas compared to those people coming from mid- or high-income communities. Another finding that I found to be particularly jarring was that communities with a high number of families with children under the age of 18, are almost twice as likely to be nature deprived as families without young children. And that that disparity is especially apparent for families of color and low-income families with children.

CURWOOD: Whoa, I mean, you think of kids needing to get outside and get their hands grubby in the dirt, and all that kind of thing. And that's not happening for less advantaged families, huh?

ROWLAND-SHEA: It's not at all, and I think that in terms of policy solutions, that has been one of the places that policymakers have been starting, at least now, and the Every Kid in a Park program is a really great example of one federal program that has started to remove the financial barriers to getting kids outdoors, that allows fourth graders and their families to enter all national parks and public lands for free during their fourth grade year of school. And so that has exposed several new generations to the wonders that are national parks and other public lands. And another program at the state level, New Mexico's new Outdoor Equity Fund, is just getting going, but it is designed to specifically correct for some of the racial and economic disparities that exist in these natural experiences.

CURWOOD: Jenny, where do Native American communities fit into the nature gap?

Fourth graders participate in an ‘Every Kid in a Park’ event at Rock Creek Park, a city park in Washington, D.C. that’s administered by the National Park Service. (Photo: BLM, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

ROWLAND-SHEA: So we looked specifically at the energy development aspect of nature loss and tried to assess which communities were most impacted by that, and did find that when you look at energy development, specifically, Native Americans are disproportionately affected by the impacts of oil, gas and coal development. We saw this especially happening in the four corners area, areas of northern New Mexico, Northern Arizona, southern Colorado, where there's a lot of federal oil and gas development on public lands, among other development activities. And you can see that especially affecting Native American populations there.

CURWOOD: So taking away something like Bears Ears so that one could drill there.

ROWLAND-SHEA: Yes, that is really a prime example. And while it may not be actually covered in this data because some of that new development is so recent, I think we will see that nature deprivation near the Bears Ears area in Utah may have some profound consequences.

CURWOOD: Now, your report on the nature gap makes several recommendations about steps that could be taken to help address unequal access to nature and nature benefits, and the first one calls for protecting at least 30% of America's lands and waters by 2030. This is a goal recommended by many scientists and supported by a number of members of Congress. How do you think "30 by 30" can best help address the nature gap?

Jenny Rowland-Shea is a Senior Policy Analyst for Public Lands at the Center for American Progress. (Photo: Courtesy of Jenny Rowland-Shea)

ROWLAND-SHEA: Yeah, so our findings really affirm the need for more ambition in nature protection, and the goal of protecting 30% of lands, of waters by 2030, which has, in addition to many members of Congress, has also been embraced by the Biden campaign, could help the country protect more natural areas in a way that ensures that benefits are more evenly and fairly distributed. And pursuing better protections for land and water is an important opportunity to kind of hit that reset button and ensure that conservation over the next decade really reflects the views and the needs of everyone.

CURWOOD: Jenny Rowland-Shea is a Senior Policy Analyst for Public Lands at the Center for American Progress in Washington and lead author of "The Nature Gap" report. Jenny, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

ROWLAND-SHEA: Thank you so much, Steve.

Related links:

- The Nature Gap report from the Center for American Progress

- Learn more about “30x30”, the plan to protect 30% of U.S. land and water by 2030

- About Jenny Rowland-Shea

[SFX SOUNDS]

Parktracks: Sounds of the Kiowa Nation Buffalo Songs

The Kiowa Gourd Dance ceremony usually is performed in a circle with a drum placed at the center. Men beat the drums and women stand or sit behind them. Both sing and dance in place, raising their feet in synchronicity with the drumbeats and swinging metal rattles from side to side. (Photo: Donovan Shortey, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: The Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division of the National Park Service has compiled more than 150 sounds from parks all over the country.

[SFX SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: In this recording members of the Kiowa Nation of the southern Great Plains sing the Buffalo Songs, traditionally rendered at the end of the Kiowa Gourd Clan ceremony.

[SFX SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: The ceremony comes from a legend in which a Kiowa warrior encountered a red wolf who was dancing and singing this song. The wolf encouraged the warrior to share the song with his people.

[SFX SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: The songs were identified by Dennis Zotigh, the Cultural Specialist at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

[SFX SOUNDS]

Related links:

- Access the full Parktracks audio experience

- Click here to learn more about the Kiowa Gourd Clan Ceremony

CURWOOD: Coming up – systemic racism and the big national environmental organizations. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Silk Road Ensemble, “Turceasca” live at TED, traditional Roma/arr.Silk Road Ensemble]

Systemic Racism and Green Groups

Many in the environmental movement remember John Muir, the founder of the Sierra Club, as a philosopher, a leader and a protector of places like Yosemite Valley, but with strong views of white supremacy. (Photo: Jim Bahn, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Like many other aspects of this country, the environmental movement has deep ties to America’s history of racism and white supremacy. Issues like pollution and climate change, even the Corona Virus, continue to take the greatest toll on Black and brown communities. And core environmental ideas like “wilderness” ignore the theft of land from Indigenous tribes. Today, the national environmental movement is dominated by white voices and often excludes people of color. Environmental justice is more local snd frequently an afterthought in green agendas. But now, as the United States confronts a history of racial injustice, powerful environmental groups like the Sierra Club are reckoning with their own history of racism. Darryl Fears covers the environment for The Washington Post, and he joins me now to discuss this moment of reflection within the environmental community. Darryl, welcome back to Living on Earth.

FEARS: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So, tell me about this announcement that the Sierra Club's executive director Michael Brune made about race in his organization recently.

FEARS: Michael Brune looked at the Black Lives Matter protests, and it was a reckoning for him and the leadership of the Sierra Club. And as a result of it, the Sierra Club made a general announcement that it was aligning itself with Black Lives Matter to say that Black lives indeed matter. And then he took it a step further, and said, not only do we recognize that Black lives matter, and this racial reckoning needs to happen in the United States, but we're going to look at the past of the Sierra Club, which was fraught with racial history, and at its founder, John Muir, who said some pretty disparaging things about people of color, including African Americans and American Indians.

CURWOOD: I think most people know a little bit about John Muir, Darryl. Many in the environmental movement, remember him as the philosopher, the explorer, the protector of places like Yosemite. Tell me a little bit about who john Muir was and how he came to found the Sierra Club.

FEARS: John Muir is of Irish descent. And he was a fairly simple man, a philosopher who love nature. He lived in California. And there, John Muir is a giant. He's called the patron saint of the wilderness. He's called the father of national parks, because he fought to preserve vast areas of land, of course, including Yosemite, what is now Sequoia National Park. He famously as a boy walked from the Midwest to the Gulf of Mexico, a kind of pilgrimage and wrote of his travels. John Muir is a legend, and particularly for the Sierra Club.

CURWOOD: So he loved the wilderness. But as the National Park System is getting put together, this is when formerly enslaved African Americans are running into the world of Jim Crow. And the US government is driving Indigenous people off the lands. How did John Muir fit into this historical moment?

Black Lives Matter supporters march on June 13, 2020, just two weeks after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. (Photo: Geoff Livingston, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

FEARS: He didn't look upon Black people respectfully. I mentioned that walk from the Midwest to the Gulf of Mexico, which would have taken him through Louisiana. And on his path through the South, he encountered African Americans who were sharecroppers and people who were just one step removed from slavery. And he said at one point that the black people he encountered were a merry bunch that pretty much kidded around all the time, and did very little work. And he said, a white man with determination and will could pick as much cotton as six Sambos and Sallies. And for your listeners, Sambos and Sallies, "ie-s," are pejoratives that are right up there with the N-word. He said of American Indians that their culture was dirty, that they were filthy and uncivilized and could largely be dismissed as a people.

CURWOOD: Of course, John Muir goes on to found the Sierra Club, one of the nation's oldest and most prestigious environmental organizations. What does this mean for the environmental movement to have some of its foundational moments and leaders rooted deeply in notions of racism and white supremacy?

FEARS: I think the same thing that it means for the country at large. The founding fathers were the same types of people. I think that what's different is that we don't learn about the white supremacist roots of conservation groups at all in school. We don't learn much about the founding fathers in school, but we don't learn anything about the supremacist roots of these groups. And it's interesting that now, 20 years into the new millennium, they feel a need to come clean about these roots when they've existed for a very long time. You're talking about Madison Grant who wrote the passing of The Great Race or the racist basis of European history that Adolf Hitler, before he became the leader of Nazi Germany, called his Bible, and Joseph Leconte and David Starr, people who believe that eugenics and who believe that inferior people should not be allowed to breed they should be sterilized for the preservation of whiteness so that there will always be more white people than people who are non-white in the United States. It's interesting that they feel compelled to come clean and talk about this now.

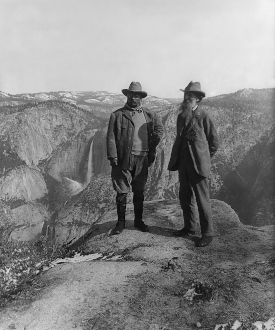

President Theodore Roosevelt (left) and environmental philosopher and Sierra Club founder John Muir (right) both advocated for racial exclusion. (Photo: GOGA Park Archives, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And Darryl, by the way, how fair is it to say that, at a local level, there are many Black people involved in environmental advocacy? The whiteness is most obvious at the national level?

FEARS: Yes, generally, when African Americans and Latinos and Native Americans are involved in this movement, they separate themselves into another category, which is the environmental justice movement. The environmental justice movement pretty much exploded into being in 1991 when Warren County, North Carolina fought this massive waste dump in this community and lost, in the judgment of environmental justice activists, very unfairly. And so in 1991, they circulated a letter and said let's meet in Washington. At that meeting in Washington, they began to call themselves environmental justice advocates and activists and they formed an organization and they move forward. And these groups work in the shadow of the big green groups. And in the shadows, obviously, of the foundations that give money to these green groups. They work in impoverished communities and they work in poverty themselves, they are barely funded, and they do the work required to keep power plants that pollute the air away from these people or to keep them honest, as much as they can.

CURWOOD: The people of color environmental movement. So Michael Brune in his essay discussing this referred to pulling down our monuments and starting with some truth telling about the club's early history. As we've seen with the Confederate battle flag, and the statues of folks from Robert E. Lee, Fort Bragg named after Of course Braxton Bragg, a notably unsuccessful Confederate general, there's a lot of pushback when these things are postulated. How successful do you think Michael Brune is being in this quest?

FEARS: It's hard to know. I mean, his quest is only a few weeks old at this point. It's interesting because the Sierra Club has numerous chapters. It has quite a few in the state of California and about one each in every other state. I think that, when Michael Brune began to draft his essay, or his blog posts are calling for almost a repudiation of some of the sayings of John Muir, he worried greatly about what the chapters in the south would say. Places like Louisiana, and Texas and Georgia, with all these chapters and all these chapters are very important to the Sierra Club. There is talk about whether this is fair, whether you should repudiate someone who was just doing what was normal at the time. I've received a number of emails saying that these groups shouldn't change at all. But those were a minority. I received quite a few emails from members of the Sierra Club saying that it's about time that we took this step. And so it'll be interesting to see how this affects the organization moving forward, because I don't think that we've seen the end of this issue.

Big green groups like the Sierra Club built their reputations on fighting to protect wilderness and nature, but have a mixed record of helping communities of color disproportionately impacted by pollution or climate change (Photo: Lida, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So Darryl, as the Sierra Club is finally confronting its racist history. There's also another reckoning going on in the big environmental groups like the Union of Concerned Scientists about diversity and inclusion, right? Can you tell me what's going on there?

FEARS: Right, the Union of Concerned Scientists made a commitment like the many of the other groups about 10 years ago, to be more inclusive in its organization and recruit more people of color onto its staff. And one of those people that recruited just three years ago is a woman named Ruth Tyson and Ruth Tyson--she's a Jamaican immigrant who came to this country when her mom was seven months pregnant with her--had been working in the environment which doesn't pay well, she was working three jobs and a friend handed her an ad about a $47,000-a-year job at the Union of Concerned Scientists and she jumped on it because she said it was more money than her parents had seen and more money that she had seen in a year. Ruth says that she gets to the Union of Concerned Scientists, and there is no real infrastructure there to support either her or her work as a person who reaches out to non-white communities. And there are few African Americans there as well. And so there is almost no camaraderie. And she describes the white people or her co-workers, her white coworkers, as fairly cold and not very communicative with her. Her work is criticized. Her ideas are dismissed. Three black women who were on her team were forced out or quit because of the treatment they received. And Ruth also noticed that every time there was some attempt to reach out to African American communities, she was recruited almost as the voice of those communities. And three years later, she finds herself very frustrated, and she's on the verge of quitting. And before she quits, she decides to write an email explaining why she's quitting the organization with only three days notice. And she starts to write the email. And three days later, the email has become 17 pages, a manifesto of searing criticism about what she encountered there. The work she was hired to do was kind of an afterthought as a result of an organization that says, Okay, well maybe we should be more inclusive and hire some black and brown people. And she felt that it was time for her to go.

Environmental issues like pollution and climate change have a hugely disproportionate effect on Black, Brown and Indigenous communities. (Photo: Andre Turcott, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Darryl by the way, how has the Union of Concerned Scientists responded since you wrote about her experience in your story?

FEARS: That was the most fascinating thing of all, because I read the manifesto 17 pages long, very long. And I thought, wow, I'm sure the Union of Concerned Scientists will say that some of this is unfair. And so I called the president of the organization and was told that he agreed with all of it. And I said, "All 17 pages?", and he said, "Yes." And in addition to that, he said he was very concerned and heartbroken that she found her treatment at the organization so unfair. And I thought that was remarkable. In fact, just as a journalist who's used to tension in these interviews and a give and take, I was kind of thrown off balance by his total agreement with her. And then I started interviewing the leaders of other organizations. Because the letter circulated everywhere. Ruth Tyson sent the letter to 200 people at the Union of Concerned Scientists, who then sent it on to basically the entire conservation field. And when I talked to the leaders at organizations, they had not only read it, but they too agreed. They said that her words rang true of what they've been told by the non white staffs at their organizations. And Michael Brune said that he found it heartbreaking, and that it aligned with the criticism that he heard at the Sierra Club.

CURWOOD: So demographically in another 20 years, majority of people in this country are going to be people of color. Already the majority of schoolchildren are people of color. So to what extent are the white dominated green groups facing, frankly, a reduction of impact given the demographic changes in this country?

FEARS: I think that's just it. I think if they don't diversify, they're really not representing everyone. They're really not representing the people they say they represent. As it stands, people of color represent 40, 41% of the population of the United States. In 2050, only 30 years from now, people of color will be a majority in the United States. And so green groups would have to change, a great deal to represent a majority of the people in the United States over those 30 years and once again, over the last 10 years, they've done a very poor job of changing themselves to do that.

A Field Medic with the Oceti Sakowin Camp of Water Protectors raises her right fist near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota. (Photo: Avery White, Oceti Sakowin Camp, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So then what comes next? These are organizations that are fighting high stakes issues, climate disruption, the loss of tropical forest that among other things, got us into this COVID pandemic problem, pollution, public health, which by the way, disproportionately affects Black, brown and Indigenous peoples much more than white people in this country. So they agree that they haven't been doing the right thing. The problems are huge. What are they going to do now in response?

FEARS: You've touched on it. These groups do great work, they do the work to protect the environment, they do try and serve their mission as best they can. But at the same time, these groups have felt that they haven't really reached out to Black and brown communities the way they should for at least a decade, and the decades since acknowledging that, they've done very little. I think that they've always known where they fit in. I think that they were comfortable with the general public not knowing and the history was largely hidden. And I think around the last time that I was on your show, I wrote an article about the lack of diversity in these groups because I had been reporting on environmental issues for about four years and everywhere I went, there were hardly any other people but white people in the room and it was stark. And after three years reporting. I asked, why is that? White people aren't the only people who are impacted by pollution and climate. And white people aren't the only people who care about the environment. And so I started really probing this question. And I started talking to the groups and I wrote a story about the lack of diversity therein and in writing that story, that's when I personally began to learn about the history. I already knew about Teddy Roosevelt. But I didn't know about John Muir's connection to white supremacy and white supremacists. And I didn't know about Madison Grant, and others. And that began my education about the origin of these groups. And so we can't really trust that they'll transform themselves 10 years from now. As a journalist, I'm just going to have to really follow them to see if they do evolve into the groups they say that they're going to evolve into. Meanwhile, the environmental justice movement is saying, look, we're gonna call on the foundations that give them money to give money to us because we are more concerned about our communities. We don't have to worry about diversifying our groups, we can do this work. We don't have to rely on these green groups to do this work. It's not just the green groups. It's the foundations that fund them. And it's whether people begin to trust the ability of groups with direct connections and direct concerns for the communities that green groups say that they're now going to represent. Perhaps environmental justice movements can do the work better than these green groups.

A Sierra Club postcard depicts an endangered bald eagle in flight. (Stephanie, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Darryl Fears covers the environment for The Washington Post. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

FEARS: Thank you. I hope I answered all your questions.

NOTE & CORRECTION: The guest erroneously stated that John Muir was Irish. John Muir was born in Scotland and emigrated to the United States with his family at the age of eleven.

Related links:

- Ruth Tyson | “An Open Letter to UCS: On Black Death, Black Silencing, and Black Fugitivity”

- Los Angeles Times | “Sierra Club Calls Out the Racism of John Muir”

- The New Yorker | “Environmentalism’s Racist History”

- The Washington Post | "Liberal, progressive — and racist? The Sierra Club faces its white-supremacist history."

[MUSIC: Christian McBride, “Right Back Around Again” on Out Here, Mack Avenue Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Anne Flaherty, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Kori Suzuki, and Jolanda Omari. Jake Rego engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts. We tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth