Women Hotshot Firefighters

Air Date: Week of September 11, 2020

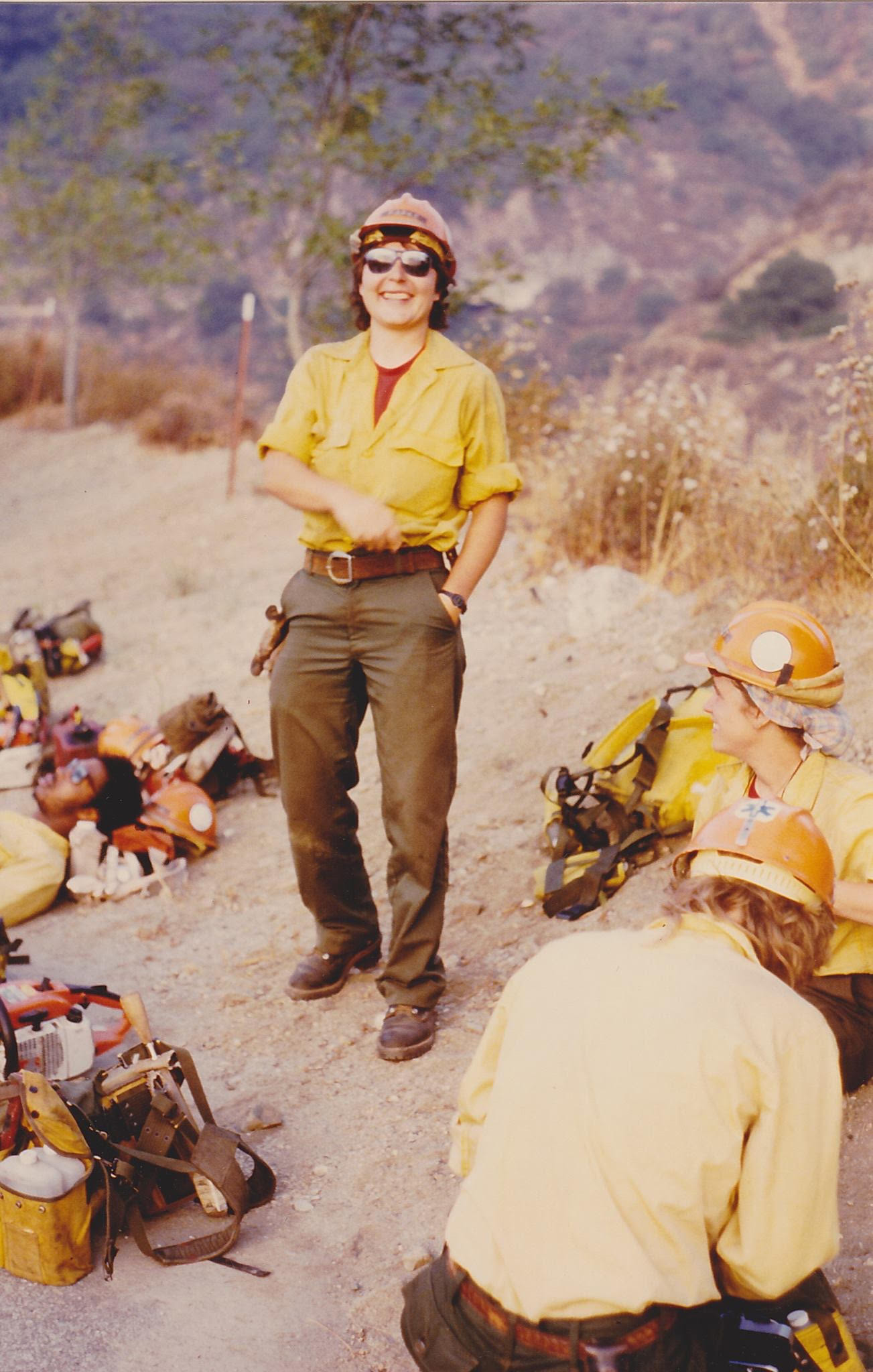

Wildland firefighters might often take on tasks such as digging ridgelines and literally fighting fire with fire. (Photo: Courtesy of Pacific Southwest Operations)

“Hotshot” crews perform some of the most physically demanding and dangerous firefighting work, and have long been male-dominated. Freelance journalist Amanda Monthei captured the stories of some of the first women hotshots for Outside Magazine. She’s worked on a hotshot crew herself, and spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb about the generational link she found between her experience and theirs.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. Hotshot firefighting crews are so named because they are deployed to the hottest, most remote areas of a wildfire. Equipped with chainsaws, shovels, and axes to put out and contain fires they spend several days at a time working in the back country and must hike in much of their food, water, and heavy equipment with them. It’s a dangerous, physically demanding job, to put it mildly. Hotshot crews got started in the 1940s but it would be another 30 years until the first women joined their ranks. Amanda Monthei recently wrote about those first female hotshot crew members for her article, “The Women Before Me” in Outside Magazine. Amanda has worked as a hotshot herself and joins me now to talk about her experience and what she learned from the first female elite firefighters. Welcome to Living on Earth!

MONTHEI: Hi, thanks for having me.

BASCOMB: It's a really physically demanding job. And historically not one that women were seen as suitable for. Can you give us a little bit of the history of hot shots and gender and how that changed?

MONTHEI: Yeah, so a lot of the work I've done recently has been about women who sort of trail-blazed the idea of what a hot shot looks like, you know, because in the 1970s, it was very much a good old boys world, it still very much is. But at that time, women, it wasn't something that was even in their worldview to consider. And in some ways, again, it's still like that today. A lot of women come to me and they're like, Wow, I didn't know this was even an option. Like I'm so psyched that you're talking more about it because I would have never considered doing it. And now I'm going into my first season on a hand crew or something. I spoke with a woman who was a hot shot in the late 70s. And she made it clear that like when she went to college, her options were being a secretary or nurse, it was never even remotely an option to work in the woods. So a lot of women were, like, really, when I say trailblazers, I mean, they were like, really pushing the envelope of what women were capable of doing at that time. And a lot of them vastly exceeded expectations, and did what a lot of women can probably relate to in male dominated jobs. They sometimes outworked and where often some of the better employees on those crews because they knew that they had to outwork the guys. They knew they had to, like, really prove that they deserved to be there. Because I think it was 1979 that this consent decree required the federal government to hire more women to these crews. You know, obviously the women that I wrote about were hired in the 1975-1977 range. But once the consent decree came about, there were quotas that needed to be filled. And once that happened, they were hiring women not necessarily on merit, but on the fact that they were women. And so that almost pushed the perception of women back a little bit. A lot of women were being pushed into the forest service and pushed into positions that they weren't necessarily qualified for, just because they wanted to fill those positions with women. They wanted to meet a quota, and that put a bad taste in a lot of people's mouths. And I think that what resulted from that still kind of holds over in a lot of land agencies today that women are only hired to fill a quota when in reality, there's a lot of reasons that crews hire women. There's a lot of positive attributes that women can bring to the table.

BASCOMB: Well, what are women bringing to the table do you think?

Amanda Monthei working as a hotshot during the Dollar Ridge fire that burned Utah’s Ashley National Forest in 2018. (Photo: Courtesy of Amanda Monthei)

MONTHEI: I get this question a lot? And it's hard to answer because you can't over generalize, you know what I mean? Like, it's easy to say like women bring the certain level of endurance like that women have a higher pain tolerance. And almost everyone I've spoken to will reiterate that a lot of the older women that I spoken with, have repeated that, that they felt that whether they were hiring women or whether they were senior women on their crews, they often found that the women were able to work longer hours able to kind of work through pain a little bit better, which is pretty important in this job. There's also the element of maybe not having as much ego that's an overgeneralization of course. Women can have ego men can be really good at not having ego but I think on a general basis, women have a little bit less ego. They're a little more maybe sympathetic of these human factors, that's what we call them in the forest service. Things like thinking through decisions a little bit more, thinking about the human elements that contribute to that decision making. Whether is your crew really hungry has your crew work 12 days in a row 12 really hard shifts in a row, are you a hundred percent confident that the state your crews in right now is going to be conducive with a safe assignment, and not just pushing your crew to its absolute limits because you want to get the job done.

BASCOMB: Now, you worked on a project where you tracked down some of the first women who held positions on hotshot crews in the Pacific Northwest. Can you tell me one of their stories, please?

MONTHEI: Yeah. So there were stories. Gina Papke told me a story about how they where on a fire in in Oregon, and they're spiked out on this ridgeline and they got so smoked in that the helicopters couldn't bring them food for three days and so they were just not eating for three days and still trying to work. And at the end of the season, when you've already worked pretty hard, this was an August, already worked hard all season and I lose weight every single fire season because you're hiking a lot, you're not eating and so you lose weight naturally. And by August, you don't have a lot of fat stores left you're like very weak and she was saying how, how difficult it was to to continue working in those conditions. And then just like the simple like logistical differences between their working hours, they didn't have radios back then. And so it was really just like a dropping a couple people off on the side of the road and saying like, see in a couple days, like go wrap that fire up on the hill on the ridge line over there. And they'd go and they do it and then they'd hike out. And they'd have to like, you know, flag somebody down on the road or like, go find a landline to call their office to say, come pick us up. So they said there was a lot more yelling back then, which I thought was kind of funny. Now, every single person almost on a crew has has a radio so we can all communicate with each other and that helps with safety a lot to letting people know where things are heating up, or what sections of the fire are problematic or, you know, having a lookout, especially, you know, making sure that somebody is looking out for you and they're at a high point where they can see what the fire is doing and let you know if anything starts going crazy. Not having all that stuff in place back then seems wild to me.

BASCOMB: Well, it sounds like these women really paved the way for other women like you to do this type of job. You know, and it's not something that I think young girls are typically taught that you can work in the outdoors that you can work in physically demanding jobs. They don't see role models in those fields. Does that ring true to you?

MONTHEI: I would say so. I would say simply because I made it all the way to the age of 26 without even knowing that wildland fire was a thing I can do before my friends, a couple of my girlfriends did it. And it really takes the one person that you know, to do something like this for you to recognize that it's actually possible for you to do it as well. And I just try to be like an example of somebody that's working in this world and enjoying it. You hear a lot about the negative parts of working in these male dominated industries. You hear a lot about the harassment and the sexist comments and the belittlement in all of this. And while I think it's very, very important to have those experiences highlighted, and for people to know what they're getting into, I also think it's important to highlight the positive elements of these jobs. I do think if we were able to just reach out and have this be a conversation when women are, you know, preteens and teenagers and like letting them know that first respinder jobs, whether it's fire, EMT stuff, search and rescue any of those jobs, unless we start like actively showing women that they can be in those positions, I don't know how we can change the demographics.

Gina Papke is one of the many trailblazers of the first U.S. Forest Service hotshots. She became the first permanent female hotshot superintendent. (Photo: Courtesy of Jerry McCollister)

BASCOMB: It sounds like some of the women that you talked to had some really difficult experiences and women still do today, as you just mentioned, but you also talk in your piece about the sentiment of you know, working hard as a hot shot made them stronger in the end, one woman described it as being tough as nails by the time she was done with this experience. Can you tell us more about that, please?

MONTHEI: Absolutely. I mean, I think it's a matter of doing hard work every day. Being away from your family all summer and being fully committed to this world six months out of the year, whether every single day is hard work or not. It's still really difficult to be away from your real life for six months a year because we're doing 14 days on two days off all summer. So during a busy summer, feasibly, we could be gone from home pretty much every day of every month from June until October with only like two to three days off a month. There's a lot of different elements that make this job difficult, and I think the least of which is the actual work itself. Everyone expects to work really hard but then you add in relationship problems you add in coughing all the time or sore throat all summer, crappy fire camp food and getting six hours of sleep a night. And it's just like, oh, yeah, like this is quite difficult. It's really a world that's very unique. Obviously, a lot of people don't understand all the elements of this world and so to find women who I can relate to on that core level, it's cool to have that sort of generational link between women that were doing this job 40 years ago, and myself who's only done it for the last two summers. It's why I chose to do the project and it's cool to like hear their experiences and hear how many parallels there are between what they experienced and what I experienced.

BASCOMB: Amanda Monthei is a freelance journalist and previously worked as a hotshot wildland firefighter. Amanda, thank you so much for taking this time with us.

MONTHEI: Thanks for having me.

Links

Click here to learn more about Amanda Monthei

Read about the first hotshot women in the U.S. Forest Service

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth