September 11, 2020

Air Date: September 11, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Mastering Fire with Fire

View the page for this story

In California, Oregon and Washington, the 2020 fire season is one for the record books, with millions of acres burned and many thousands of people displaced. Fires are inevitable in much of the West due to the region’s ecology, but devasting megafires aren’t, according to Timothy Ingalsbee, founding director of Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics, and Ecology (FUSEE). He joins Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to discuss how fire management can keep megafires from erupting and keep communities safe. (11:18)

Women Hotshot Firefighters

View the page for this story

“Hotshot” crews perform some of the most physically demanding and dangerous firefighting work, and have long been male-dominated. Freelance journalist Amanda Monthei captured the stories of some of the first women hotshots for Outside Magazine. She’s worked on a hotshot crew herself, and spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb about the generational link she found between her experience and theirs. (09:08)

Wetlands Mitigate Hurricane Damage

/ Aynsley O'NeillView the page for this story

Hurricane Laura hit the Gulf Coast as a Category 4 at the end of August 2020, but the impact of the killer hurricane was less deadly than many had feared, in part due to the buffer provided by coastal wetlands. Living on Earth's Aynsley O'Neill reports. (02:34)

Millions of Americans Lack Clean, Affordable Water

View the page for this story

Clean water is a basic human right, according to the United Nations. Yet for millions of Americans, it can still be expensive and hard to come by. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb speaks with Nina Lakhani, an environment reporter at the Guardian, which recently launched a year-long project investigating water inequities in the US. (09:29)

Beyond the Headlines

View the page for this story

In this week’s edition of Beyond the Headlines, Peter Dykstra joins Bobby Bascomb to discuss calls for climate change to be a centerpiece topic in the upcoming Presidential debates. This week’s segment also covers the EPA announcement that the agency would shift focus away from climate change, and towards “community cleanups”. Finally, looking back through history, the pair discuss the 30th anniversary of the landmark book Dumping in Dixie by “the father of environmental justice,” Prof. Robert Bullard. (04:41)

BirdNote®: New Zealand’s Kakapo

View the page for this story

Islands are famously home to a huge diversity of animals found nowhere else on Earth. In New Zealand, an edemic and peculiar bird called the Kakapo is making a comeback. BirdNote’s Michael Stein reports on this one-of-a-kind big bird. (02:03)

Cutting Carbon for Healthier Kids

View the page for this story

Research now shows that a landmark program aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic has helped lead to healthier kids. States that participate in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, also known as RGGI, have collectively cut carbon and fine particulate emissions from the power sector, leading to cleaner air overall and fewer cases of asthma, autism, and preterm birth. Dr. Frederica Perera is the Founding Director of the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health and lead author of the new study, and joins Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to discuss. (07:25)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Timothy Ingalsbee, Nina Lakhani, Amanda Monthei, Dr. Frederica Perera

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Aynsley O’Neill, Michael Stein

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

New research exposes the water affordability crisis in the United States.

LAKHANI: If you’re struggling to pay your water bill, it’s very likely that you’re struggling to pay lots of bills. So just because somebody threatens you with having your water shut off or puts a lien on your house doesn’t mean you’ll suddenly be able to magic up the money and pay the bill.

BASCOMB: Also, stories of the first female hotshot fire fighters.

MONTHEI: I spoke with a woman who was a hotshot in the late 70s and when she went to college her options where being a secretary or a nurse. It was never even remotely an option to work in the woods. So a lot of these women were like trailblazers they were really pushing the envelope of what women where capable of doing at that time. (:17)

DOERING: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Mastering Fire with Fire

A wildfire in Goleta, California. (Photo: Glen Beltz, Flickr, CC By 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. For California, Oregon, and Washington, the 2020 wildfire season is one for the record books. With the flames and destruction captured on the CBS Evening News.

REPORTER: The wildfires burning throughout the West are especially destructive this year. Scientists say they’re fueled by climate change, the fires now ripping through several states, leaving a path of immeasurable destruction.

DOERING: With months still to go in this year’s fire season, California alone has already seen more acres burn than any other year on record -- more than 2.6 million acres so far. But this fiery destruction isn’t inevitable. In fact, experts like Timothy Ingalsbee say more fire, not less, is what’s needed to help tame these megafires. He’s the founding director of Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics, and Ecology. Welcome to Living on Earth!

INGALSBEE: Thank you. Great to be here.

DOERING: So this year, we've seen the biggest wildfire season in California history. Why are we seeing such big fires that burned so many acres? And how did we get to this point?

INGALSBEE: Well, there's a variety of reasons but the primary driver is climate change, prolonged droughts and record heat waves, combined with freakish lightning storms, that are creating these giant fire complexes that's multiple ignitions simultaneously. And then, you know, people living all over the landscape, particularly in very fire prone environments. And then, you know, combined with a past century or more of excluding fire from the land and fighting all fires, we've just got all the prime ingredients for these kinds of, you know, fire storm activities.

DOERING: So what is really going on with climate change and wildfires? Why does it make wildfires so much more common and large when they happen in California?

A member of the San Francisco Fire Department. (Photo: Thomas Hawk, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

INGALSBEE: Well, in terms of just accumulating the amount of air you're burned wildfire seasons are lengthening, because you know, the winter snows and rains are coming later, and that snow was melting earlier. And it's just in the last 20-30 years, it's extended the fire season over two months. And that has a toll on wildland firefighters. They are just beat up by mid summer. And in California in particular, it's almost the end of this notion of a fire season. Year round, various places could be, you know, prone to ignition and, you know, fire spreading. So it's lengthy in the fire season. And then the rising temperatures makes everything on the ground easier to ignite. And once ignited, faster spread. And that's the real issue. What's happening today why the fires are so big, they're moving so fast, way faster than firefighters can kind of get out ahead, some cases faster than people can flee.

DOERING: So you say that there's a solution. We don't have to live like this with these fires completely getting out of control. What would you recommend?

INGALSBEE: The best thing that affects fire is fire itself. Those fires that are burning, you know, in spring and late, late summer fall under moderate conditions are doing very vital work for the ecosystem and keeping it stable, sustainable. This summer is clear. If some of those fires last summer, we hadn't been so aggressively attacking and putting out those would have provided buffers this year for the fires that are burning under these extreme weather conditions. Last year, they're moderate weather conditions and they would have done really good things. This year, that same areas that we put out here are now burning, you know, out of our control.

DOERING: Right? I mean, so correct me if I'm wrong, but I thought that you know, when a fire is sparked in a wilderness area, for whatever reason, I was under the impression that fire managers kind of watch it. If it's going to threaten structures, then they'll move in. But right now, in terms of fire policy, are we letting any of these, you know, fires that aren't necessarily threatening structures, are we letting them burn or are we just sort of stamping them out as soon as they start?

INGALSBEE: Well, the beginning of the season with the best of intentions relate to the Coronavirus crisis, the forest service said we're going to fight off fires aggressively upon detection. This is going back to the fire policies of the 1930s, what they called the 10 a.m. policy. So, you know, in June in July, they were sending hundreds of crews, even to remote wilderness areas like the Trinity Alps wilderness area, the Ventana wilderness area, fighting fires, they're trying to put them out and stop the smoke. Well, lo and behold, we had this huge lightning storm, fires everywhere down in the Central Valley and you know, Santa Cruz, I mean and hundreds of crews were stuck in the wilderness trying to do, you know, places shouldn't have been, doing things they shouldn't be doing when they were sorely needed elsewhere. And so we got caught there.

A tower of smoke visible from the road in Azusa, California. (Photo: Russ Allison Loar, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: So it sounds like you're saying this is a recent change this year that we're harkening back now to policies from the 1930s, where we're gonna fight all fires. So for a while, for several decades, we weren't necessarily putting out all the fires, is that correct?

INGALSBEE: Well, we've made that policy. The Forest Service and National Parks were made that policy in the 60s and late 70s, from fire control, you know, fight all fires to fire management. But that policy was made on paper, not necessarily in practice, in actual practice, the Forest Service, for example, still aggressively attacks, you know, 90 to 95% of all wildfires. It's just the bare minimum that they actually, you know, manage and these are some of the most remote wilderness areas. Well this year, they kind of went backwards on even that small amount of fires that they would manage. So yeah, it's been attack all fires. And it's a slippery slope. They said it's just just this year, just while we have the Coronavirus crisis, try to eliminate smoke, but we're going to have the virus with us next year. We're certainly going to have climate change with us next year, we're going to have probably even more wildfire activity. This is the reality now while there's increasing wildfire activity, and it's you know, we done and tried our best to change nature to our liking. It's time that we start getting a grip on our own behavior and the way we live our lives, you know, with these flammable buildings, fueled by all this fossil fuel burning, and that's what something that we can control. We can solve for those those issues and those problems. Once we do that, once we protect communities from fire, then we can start, you know, talking about how to manage and restore ecosystems with fire.

DOERING: You know, you're talking about these things that we know we can do building more resilient communities and harnessing fire. Why isn't the policy caught up?

INGALSBEE: Well, it's more than policy. There's there's other drivers like culture, for example. I mean, people have been socially conditioned to fear fire. And this is really a complete anomaly to what our species is, you know, part of our species' success was our ability and our knowledge to use fire. We're the only species that knows how to start fire. And probably the only one crazy enough to try to stop all fires, especially that have, you know, been been part of the Earth for 400 million years. And part of just about every indigenous people's ability to survive on this continent for tens of thousands of years. So it's culture but it's also kind of politics and bureaucracy, and the government agencies are all, you know, fired up to wage war on wildfire. And there's very powerful political and economic interests with vested stakes and perpetuating that kind of war like mode. And so in other interests that are trying to opportunistically use wildfires to further other agendas, you know, let's log those trees before they burn. that'll solve the problem. Well, no, it's a spurious connection. And it's actually counterproductive because that's what's burning in California is not so much forest. But was what the shrub lands and grasslands that were grown in the wake of forest that were gone.

DOERING: Right. So it sounds like there's an incentive for, you know, this war like mode that you're saying the just attacking fire whenever we can. But I'm wondering to what extent is there also an economic argument to be made in favor of sustainable preventative fire management using some controlled burning perhaps rather than simply reacting on an emergency basis to mega fires.

A forest fire in Plumas County, California. (Photo: Fueling Creative Fire, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

INGALSBEE: Well, right now we we spend on the scale of billions of tax dollars every year in emergency fire suppression. If we would just take a portion of that and invest in protecting, you know, preparing homes and communities, let's say replace every rural home in America with a metal roof. That alone would increase that structure's ability to survive wildfire over 90%, and this is a matter of physics, okay. Now that would be very expensive, but that would be a one and done cost. And then that home, that structure, would be safe from, you know, embers igniting its roof. That would be expensive, but one time costs versus billions spent every year on emergency fire suppression, hundreds of millions more and all these fuels reduction projects that must be done every year in perpetuity.

DOERING: Dr. Inglesby before you go, what's something about wildfires that you really wish that others could understand?

INGALSBEE: Majority of fires in wild lands, okay, those are real wildfires. They're not these giant tsunamis of flame that consume everything in its path. They're really spotty. And you know, most of the burned acres come from flames on the ground. And yeah, they may torch up a tree or a cluster of trees here. But they're really diverse in their behavior and effects. And this pyrodiversity plays a major role in biodiversity. So these wildfires in wild places are really how those places evolved and really require that this kind of ecological stimulus, if you will, it's not a natural disturbance. It's an ecological stimulus. But those fires are different from the ones that affect our homes communities. These urban wildfires are truly disasters. They destroy homes and they kill people. So they're really two different fires. And we got all of our focus on those wildfires. And we really need to start focusing on those urban fires.

DOERING: Timothy Inglesby is founding director of FUSEE, firefighters United for Safety, Ethics and Ecology. Thank you so much, Timothy.

INGALSBEE: Thank you. It's a pleasure and everyone keeps safe out there.

Related links:

- About Timothy Ingalsbee

- ProPublica | “They Know How to Prevent Megafires. Why Won’t Anybody Listen?”

[MUSIC: Elvis Presley, “Fever” on 100 Songs for Magic Moments, by John Davenport/Eddie Cooley, RCA Victor]

BASCOMB: Coming up – We’ll hear the history of women as elite back country fire fighters. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Einstein’s Little Homunculus, “Music For a Found Harmonium” on Double Redundancy, by Simon Jeffes, self-published]

Women Hotshot Firefighters

Wildland firefighters might often take on tasks such as digging ridgelines and literally fighting fire with fire. (Photo: Courtesy of Pacific Southwest Operations)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. Hotshot firefighting crews are so named because they are deployed to the hottest, most remote areas of a wildfire. Equipped with chainsaws, shovels, and axes to put out and contain fires they spend several days at a time working in the back country and must hike in much of their food, water, and heavy equipment with them. It’s a dangerous, physically demanding job, to put it mildly. Hotshot crews got started in the 1940s but it would be another 30 years until the first women joined their ranks. Amanda Monthei recently wrote about those first female hotshot crew members for her article, “The Women Before Me” in Outside Magazine. Amanda has worked as a hotshot herself and joins me now to talk about her experience and what she learned from the first female elite firefighters. Welcome to Living on Earth!

MONTHEI: Hi, thanks for having me.

BASCOMB: It's a really physically demanding job. And historically not one that women were seen as suitable for. Can you give us a little bit of the history of hot shots and gender and how that changed?

MONTHEI: Yeah, so a lot of the work I've done recently has been about women who sort of trail-blazed the idea of what a hot shot looks like, you know, because in the 1970s, it was very much a good old boys world, it still very much is. But at that time, women, it wasn't something that was even in their worldview to consider. And in some ways, again, it's still like that today. A lot of women come to me and they're like, Wow, I didn't know this was even an option. Like I'm so psyched that you're talking more about it because I would have never considered doing it. And now I'm going into my first season on a hand crew or something. I spoke with a woman who was a hot shot in the late 70s. And she made it clear that like when she went to college, her options were being a secretary or nurse, it was never even remotely an option to work in the woods. So a lot of women were, like, really, when I say trailblazers, I mean, they were like, really pushing the envelope of what women were capable of doing at that time. And a lot of them vastly exceeded expectations, and did what a lot of women can probably relate to in male dominated jobs. They sometimes outworked and where often some of the better employees on those crews because they knew that they had to outwork the guys. They knew they had to, like, really prove that they deserved to be there. Because I think it was 1979 that this consent decree required the federal government to hire more women to these crews. You know, obviously the women that I wrote about were hired in the 1975-1977 range. But once the consent decree came about, there were quotas that needed to be filled. And once that happened, they were hiring women not necessarily on merit, but on the fact that they were women. And so that almost pushed the perception of women back a little bit. A lot of women were being pushed into the forest service and pushed into positions that they weren't necessarily qualified for, just because they wanted to fill those positions with women. They wanted to meet a quota, and that put a bad taste in a lot of people's mouths. And I think that what resulted from that still kind of holds over in a lot of land agencies today that women are only hired to fill a quota when in reality, there's a lot of reasons that crews hire women. There's a lot of positive attributes that women can bring to the table.

BASCOMB: Well, what are women bringing to the table do you think?

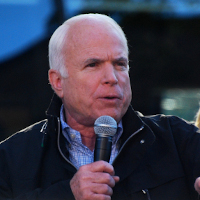

Amanda Monthei working as a hotshot during the Dollar Ridge fire that burned Utah’s Ashley National Forest in 2018. (Photo: Courtesy of Amanda Monthei)

MONTHEI: I get this question a lot? And it's hard to answer because you can't over generalize, you know what I mean? Like, it's easy to say like women bring the certain level of endurance like that women have a higher pain tolerance. And almost everyone I've spoken to will reiterate that a lot of the older women that I spoken with, have repeated that, that they felt that whether they were hiring women or whether they were senior women on their crews, they often found that the women were able to work longer hours able to kind of work through pain a little bit better, which is pretty important in this job. There's also the element of maybe not having as much ego that's an overgeneralization of course. Women can have ego men can be really good at not having ego but I think on a general basis, women have a little bit less ego. They're a little more maybe sympathetic of these human factors, that's what we call them in the forest service. Things like thinking through decisions a little bit more, thinking about the human elements that contribute to that decision making. Whether is your crew really hungry has your crew work 12 days in a row 12 really hard shifts in a row, are you a hundred percent confident that the state your crews in right now is going to be conducive with a safe assignment, and not just pushing your crew to its absolute limits because you want to get the job done.

BASCOMB: Now, you worked on a project where you tracked down some of the first women who held positions on hotshot crews in the Pacific Northwest. Can you tell me one of their stories, please?

MONTHEI: Yeah. So there were stories. Gina Papke told me a story about how they where on a fire in in Oregon, and they're spiked out on this ridgeline and they got so smoked in that the helicopters couldn't bring them food for three days and so they were just not eating for three days and still trying to work. And at the end of the season, when you've already worked pretty hard, this was an August, already worked hard all season and I lose weight every single fire season because you're hiking a lot, you're not eating and so you lose weight naturally. And by August, you don't have a lot of fat stores left you're like very weak and she was saying how, how difficult it was to to continue working in those conditions. And then just like the simple like logistical differences between their working hours, they didn't have radios back then. And so it was really just like a dropping a couple people off on the side of the road and saying like, see in a couple days, like go wrap that fire up on the hill on the ridge line over there. And they'd go and they do it and then they'd hike out. And they'd have to like, you know, flag somebody down on the road or like, go find a landline to call their office to say, come pick us up. So they said there was a lot more yelling back then, which I thought was kind of funny. Now, every single person almost on a crew has has a radio so we can all communicate with each other and that helps with safety a lot to letting people know where things are heating up, or what sections of the fire are problematic or, you know, having a lookout, especially, you know, making sure that somebody is looking out for you and they're at a high point where they can see what the fire is doing and let you know if anything starts going crazy. Not having all that stuff in place back then seems wild to me.

BASCOMB: Well, it sounds like these women really paved the way for other women like you to do this type of job. You know, and it's not something that I think young girls are typically taught that you can work in the outdoors that you can work in physically demanding jobs. They don't see role models in those fields. Does that ring true to you?

MONTHEI: I would say so. I would say simply because I made it all the way to the age of 26 without even knowing that wildland fire was a thing I can do before my friends, a couple of my girlfriends did it. And it really takes the one person that you know, to do something like this for you to recognize that it's actually possible for you to do it as well. And I just try to be like an example of somebody that's working in this world and enjoying it. You hear a lot about the negative parts of working in these male dominated industries. You hear a lot about the harassment and the sexist comments and the belittlement in all of this. And while I think it's very, very important to have those experiences highlighted, and for people to know what they're getting into, I also think it's important to highlight the positive elements of these jobs. I do think if we were able to just reach out and have this be a conversation when women are, you know, preteens and teenagers and like letting them know that first respinder jobs, whether it's fire, EMT stuff, search and rescue any of those jobs, unless we start like actively showing women that they can be in those positions, I don't know how we can change the demographics.

Gina Papke is one of the many trailblazers of the first U.S. Forest Service hotshots. She became the first permanent female hotshot superintendent. (Photo: Courtesy of Jerry McCollister)

BASCOMB: It sounds like some of the women that you talked to had some really difficult experiences and women still do today, as you just mentioned, but you also talk in your piece about the sentiment of you know, working hard as a hot shot made them stronger in the end, one woman described it as being tough as nails by the time she was done with this experience. Can you tell us more about that, please?

MONTHEI: Absolutely. I mean, I think it's a matter of doing hard work every day. Being away from your family all summer and being fully committed to this world six months out of the year, whether every single day is hard work or not. It's still really difficult to be away from your real life for six months a year because we're doing 14 days on two days off all summer. So during a busy summer, feasibly, we could be gone from home pretty much every day of every month from June until October with only like two to three days off a month. There's a lot of different elements that make this job difficult, and I think the least of which is the actual work itself. Everyone expects to work really hard but then you add in relationship problems you add in coughing all the time or sore throat all summer, crappy fire camp food and getting six hours of sleep a night. And it's just like, oh, yeah, like this is quite difficult. It's really a world that's very unique. Obviously, a lot of people don't understand all the elements of this world and so to find women who I can relate to on that core level, it's cool to have that sort of generational link between women that were doing this job 40 years ago, and myself who's only done it for the last two summers. It's why I chose to do the project and it's cool to like hear their experiences and hear how many parallels there are between what they experienced and what I experienced.

BASCOMB: Amanda Monthei is a freelance journalist and previously worked as a hotshot wildland firefighter. Amanda, thank you so much for taking this time with us.

MONTHEI: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Click here to learn more about Amanda Monthei

- Read about the first hotshot women in the U.S. Forest Service

- Learn More about becoming a hotshot

[MUSIC: Cheb Mami, “Meli Meli” on Meli Meli, by Mami/Mami, Mondo Melodia]

Wetlands Mitigate Hurricane Damage

Louisiana’s wetland ecosystem took the brunt of Hurricane Laura in late August 2020. (Photo: CWPPRA, Costal Wetlands Planning Protection and Restoration Act, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

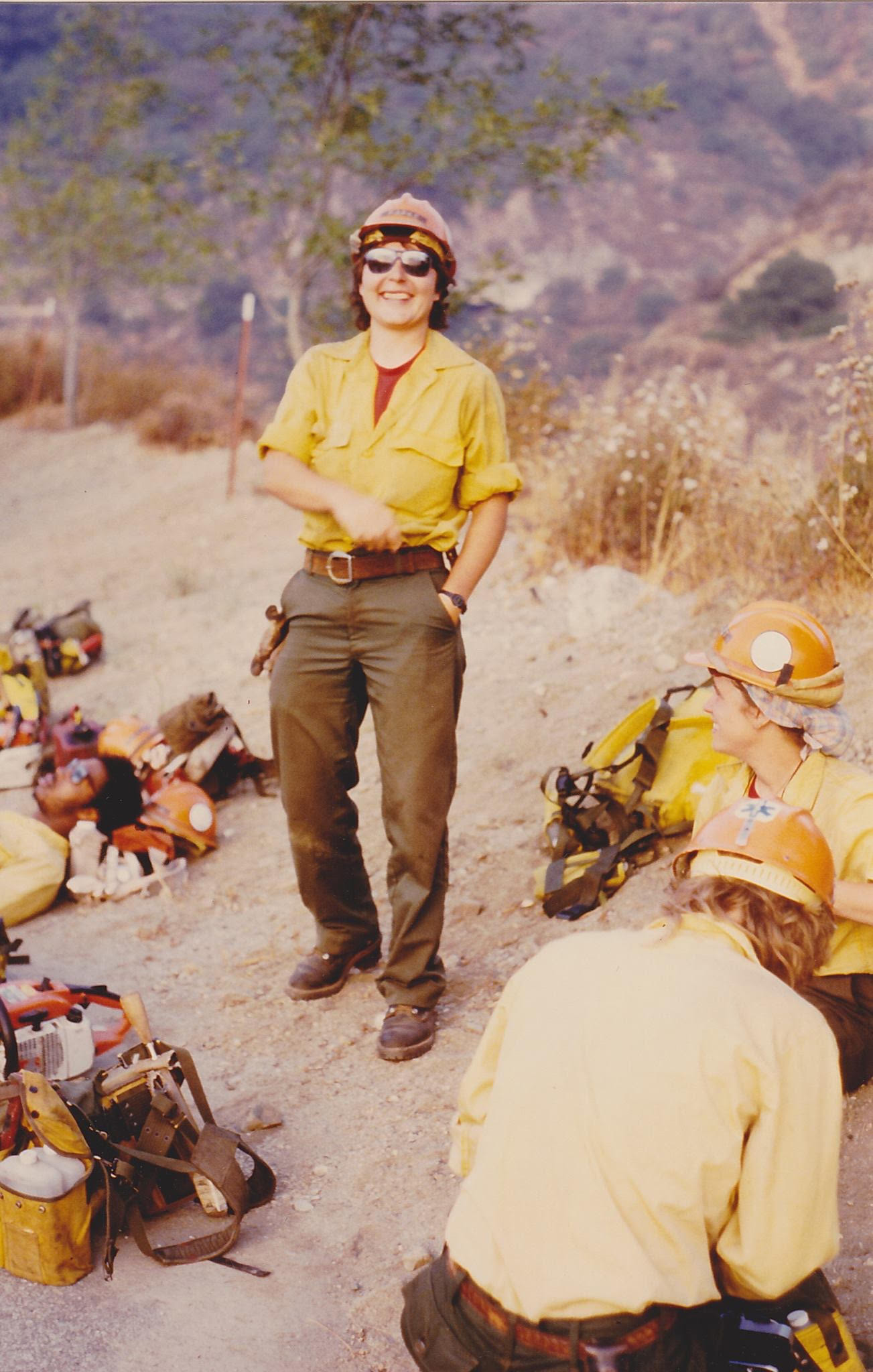

DOERING: From fires we turn now to floods. Both are natural disasters scientists tell us will be more frequent and severe with climate change. Hurricane Laura hit Louisiana as a Category 4 storm at the end of August but the killer hurricane was actually less deadly than many feared. Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill has more.

O’NEILL: Hurricane Laura had the strongest sustained windspeed of any hurricane on record to make landfall in Louisiana. And the storm surge was expected to be catastrophic for inland communities. But the damage wasn’t actually all that bad, according to many people in the region, including Governor Greg Abbott of Texas.

GOV. ABBOTT: As I ask everybody how they feel about working their way through this hurricane, everybody pretty much had the same phrase. And that is: we dodged a bullet. It could have been far worse.

O’NEILL: With roughly 70 casualties and about $9 billion dollars in repairs, the loss of life and costs of Laura are only a fraction of what was expected ahead of the hurricane. Mass evacuations certainly saved lives but the biggest life saver was where the storm hit. The hurricane made landfall at the marshes that sit along the Louisiana-Texas border. And on the Gulf Coast, wetlands like those are crucial to protecting inland communities from the natural disasters.

Hurricane Laura, here viewed from the International Space Station, made landfall along the Gulf Coast as a Category 4 hurricane. (Photo: NASA Johnson, Flickr, Public Domain)

When waves come crashing against the shoreline, wetlands absorb the impact and reduce the intensity of the storm surge and flooding. In fact, scientists estimate that every 2.7 miles of coastal wetlands reduce storm surge inland by a foot – so long as that wetland is in good condition. But wetlands are frequently destroyed or degraded for coastal development. Wetlands ecologist and Loyola University professor Bob Thomas says destroying wetlands to build a canal at the end of the Mississippi River was a disaster for the region when it comes to mitigating hurricane damage.

THOMAS: If you would have never built the Mississippi Gulf Outlet, when Katrina came in and all that water was pushed across toward New Orleans most of it would have been absorbed and you would have had maybe one or two feet hit those 17 foot high levees. But instead, it was wide open water, and all that water came in and literally topped over some of the levees.

O’NEILL: It’ll take some time to see how well the wetlands are able to bounce back after Hurricane Laura, but ecologists say we need to protect and support these crucial ecosystem services. They are our first line of defense against deadly hurricanes, provided to us for free from Mother Nature. For Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Related links:

- WWL-TV, CBS | “Could Healthy Wetlands Have Blunted Hurricane Laura’s Destruction?”

- USA TODAY | “Hurricane Laura’s ‘Unsurvivable’ Storm Surge: It Looks Like Louisiana Was Spared, but Some Rural Areas Likely Hit Hard”

- More from Governor Abbott of Texas

[MUSIC: Kate Magdalena, “The Water Is Wide” on Acoustic Rainbow – Volume 50, traditional, Acoustic Rainbow]

Millions of Americans Lack Clean, Affordable Water

Cover art for the Guardian’s new series on water inequities in the US. (Image: Erre Galvez)

BASCOMB: Access to safe drinking water is a basic human right, according to the United Nations. Yet, millions of Americans can’t afford their water bills and the water they do have is contaminated and unsafe to drink. Nina Lakhani is an environmental justice reporter for the Guardian and recently completed a year-long investigation into the problem of access to safe drinking water in the United States. Nina, welcome to Living on Earth.

LAKHANI: Thank you very much.

BASCOMB: In your research, you found that the cost of water has gone up by an average of 80% between 2010 and 2018 and more than 150% in the case of Austin, Texas. Why is that? Why is water suddenly so expensive?

LAKHANI: So there is a few different reasons, I think fundamentally that the federal government funding for water systems peaked in the late 70s. So there was an infrastructure boom when we had the EPA created and the Safe Water Act and the Drinking Water Act were approved, but funding for water systems has declined since then. And even revolving funds that states can apply to have been diminishing over time, water utilities are being left to deal with the climate crisis. So in you know, in parts of the country like the southwest, for example, which have been under drought for years now, the water infrastructure has to be adapted to be able to cope with that, the water and the sewage infrastructure and local waters departments are left to raise this revenue. And the way that they do that is by raising tariffs. So the cost of water and sewage goes up every year in many cases, and also by taking out loans on the market. And obviously, those loans have to be repaid. And those costs are then also transferred back to water users.

BASCOMB: And of course, if people can't afford to pay their water bills, that leaves the water utility without the income they need to provide safe, affordable drinking water. I mean, it's easy to see how that becomes a pretty vicious cycle.

A reservoir in Oregon. (Photo: Peter Roome, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

LAKHANI: That's right, I mean, without federal funding, this is a problem that's only going to escalate and affect a growing number of people. But also water utility companies could be doing things differently. What we've seen is that many water departments are using punitive measures to try and force people into paying. And the two main measures that we've seen being used are shut offs that people have in their water shut off because of unpaid bills. Or having liens put on their houses, which increases the risk of foreclosure on their house. The thing is, if you're struggling to pay your water bill, it's very likely that you're struggling to pay lots of bills, you know. And so just because somebody threatened you with having your water shut off, or puts a lien on your house, doesn't mean you're suddenly going to be able to magic up the money and pay the bill. You know just actually, by increasing bills and not thinking about affordability, water departments are not going to increase revenue. The research that we've done, has shown that by making bills tied to affordability so you charge people based on their income levels, on their ability to pay, water companies can increase their revenue. You have to have water to be able to live, to be able to cook to be able to clean to be able to stay healthy. People are willing to pay. It's just that if they can't pay they can't pay.

BASCOMB: Right. Well, you wrote about a specific man in your story. His name is Albert Pickett, and he lives in East Cleveland, Ohio. He fell behind on his water bills and it ultimately cost him his home. Can you tell us his story, please?

Many Americans without running water often have to purchase bottled water. (Photo: Daniel Orth, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

LAKHANI: Sure. So Mr. Albert Pickett is 60 years old. And he, you know, grew up in this, you know, really what I think was probably a very nice detached corner house in East Cleveland, which is a predominantly African American neighborhood, a low income neighborhood, and he grew up there with his parents and his siblings. And his mother, his dad died some years ago, his mother died in 2013 from Alzheimer's. And when she died in the years previous she had got behind in her water bills, in her property taxes, you know, I'm sure as part of sort of the nature of the disease, really, and so then when he moves back into the family home, there's an outstanding water bill that he just can't afford to pay. He goes to Cleveland water department in order to get onto a payment plan, but he doesn't have the deposit that they're asking for as a down payment. And so they shut off his water in 2013. And so he has been without water ever since then, borrowing jars or tanks of water bottles of water from neighbors so that he can wash, flush the toilet, buying water in order to take his medicine learn to cook and to drink. And then in 2018 you know, his luck just took a dire turn for the worse. He suffered a really severe stroke, and relatedly he fell and fractured his spine and damaged various internal organs and he ended up in a nursing facility for almost a year. When he came out of this facility, he was like he's really frail, like walks of a walking frame. He’s got a tremor, you know, lots of ongoing health issues. And a small fire started, but he didn't have any water to put out the start of that fire. He was trying to stamp it out but couldn't and by the time The fire service came, his house burnt down. I mean, I went to interview him, I went to the house. And it's just an absolute burnt out shell, you know, the whole front of it is collapsed, the roof is completely destroyed. And so since then that was in October of last year, despite his health problems, he's been sleeping on people's couches, in his car, at shelters on the odd night, and it just utterly ruined his life. You know, he talks about just the how not having water just took away all of his dignity. I mean, he used to look after his grandkids at the house. But soon as the water got turned off, he couldn't have his grandkids there. I mean, how can you have children there when you're changing nappies, and it's just not safe and healthy to do so. So yeah, it just had an absolute devastating impact on him.

BASCOMB: And you're right that people of color are disproportionately subject to having their water turned off and a lien put on their homes for back water payments. Can you tell me more about that, please?

In New Orleans, and some other southern communities, municipal and privately supplied water is taken from the Mississippi River, which has been contaminated by agricultural runoffs and pollution. (Photo: Mississippi Water Management, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

LAKHANI: Yeah, in some of the cities, I've reported forming some of the cities we analyzed, that is what lawyers and advocates are alleging. In Cleveland, there is a lawsuit that has been brought forward by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund alleging a systemic racism in the way of that liens are attached to houses. And in the case of Cleveland, which is one of the cities that you know, that we investigated, you can see there are clusters of houses, you know, where liens have been attached, which are more disproportionately predominant in black neighborhoods compared to white neighborhoods, even if you take into account income levels. That's what that lawsuit alleges.

BASCOMB: And just adding insult to injury, I mean, the cost of water is going through the roof, but the quality of that water in many cases is far worse than it used to be. How common is it for the water supply to be polluted or unsafe, as is the case in Flint, Michigan and the lead problem there?

LAKHANI: Yeah, I mean, it's this perverse sort of, you know, double whammy isn't it that you know, people are having to pay more for water and their water is contaminated. I mean New Orleans is one of the cities that we studied where people have huge concerns about the quality of their water, you know that their water comes from the Mississippi River. The water that comes to them has been polluted by big agriculture in Iowa, you know all the states coming down. So the by the time the water gets to them, it's just, I mean, the quality is dire, right. I mean, nobody willingly is drinking the tap water in New Orleans. You know, they're either spending money on bottled water, which means that they are effectively paying to water bills every month, a water bill to the utility company and to water bottlers right, because they've been forced to do or they are buying filters to install into their homes.

BASCOMB: And looking broadly at the problem across the United States. What do you think should be done to ensure that all Americans have access to safe, affordable drinking water, and what's the role of the federal government in really addressing this problem?

LAKHANI: Yeah, I don't think that can be achieved without the federal government. There are numerous pieces of legislation around. The one that I think is most comprehensive is the Water Act, which is co sponsored by Bernie Sanders in the Senate, and Brenda Lawrence in Congress. And that is calling for $30 billion of guaranteed federal funding every year for 20 years, in order to upgrade water systems that upgrade infrastructure, water and sewage, so that all of the federal standards when it comes to quality and safety are met, and that money would also include some money to help low income households pay for these increasing bills so that no one's water is being shut off.

BASCOMB: Nina Lakhani is the Environmental Justice reporter at The Guardian, Nina, thank you so much for taking this time with me.

LAKHANI: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- More from Nina Lakhani

- The Guardian’s series on water inequities in the US

[MUSIC: R. Carlos Nakai, “Alpine Dawn” on Sanctuary, by R. Carlos Nakai, Canyon Records]

DOERING: Coming up – A new study finds that reducing greenhouse gas emissions can lead to improved health in children. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Sonny Rollins, “Jazz A Juan 2005” live]

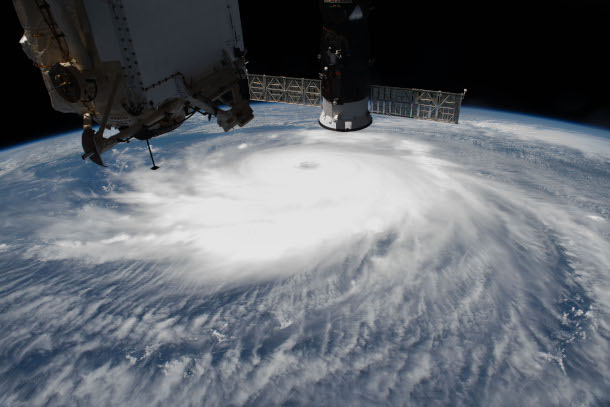

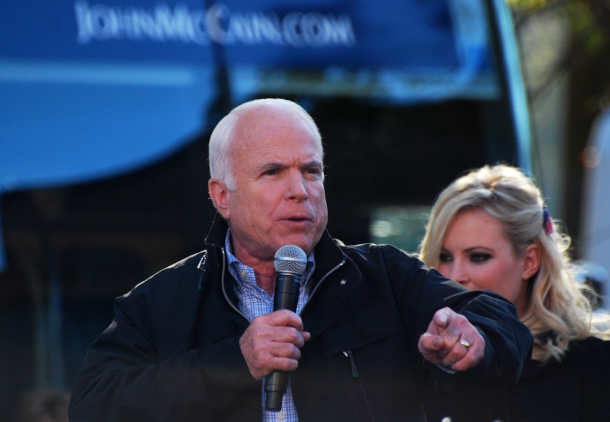

Beyond the Headlines

John McCain, the ‘Maverick’ was the last Republican presidential candidate to be asked about climate change on the debate stage. Now 70 House Democrats have requested that change in this year’s debates. (Photo: Rona Proudfoot, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. It’s time now for a look Beyond the Headlines with Peter Dystra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN dot org and Daily Climate dot org. Hey Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby is of course getting into the thick of election time. This past week 70 democrats from the House of Representatives sent a letter to media organizations demanding that climate change be a centerpiece of the 2020 presidential debates.

BASCOMB: Well, I do remember in 2016, there was no mention of the environment or climate change specifically in the debates. But when was the last time it did come up in a presidential debate?

DYKSTRA: Not in 2016, as you said, not in 2012. But the last time was in 2008, where the moderator Bob Schieffer asked a question, except not about climate change. He said climate control, which is of course, a term not used in climate science. It's a term used in the plumbing and heating industry.

BASCOMB: He just misspoke then?

DYKSTRA: He misspoke. He was very politely corrected by the late Senator McCain.

SCHIEFFER: Let's talk about energy and climate control, every president since Nixon has said what both of you --

MCCAIN: Climate change

SCHIEFFER: --climate change? Yes

DYKSTRA: Both McCain and Obama went on to give somewhat evasive answers, not talking about climate change and its causes. But talking about energy independence.

BASCOMB: Well, these 70 democratic house legislators are hoping to change that this time around. What else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: In the EPA, which is called the Environmental Protection Agency, although some people would take issue with how protective they are of the environment these days, the administrator Andrew Wheeler, who of course, is a former lobbyist for big coal, announced a shift away from climate change as an EPA priority and toward community cleanups

On September 4th, Andrew Wheeler announced the EPA would shift away from action on climate change, and instead focus its resources on ‘community cleanup’. (Photo: US EPA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: Community cleanups, okay, I mean, I've heard President Trump say many times that he wants crystal clear air crystal clear water as he puts it, but of course, this administration doesn't have a very good track record of protecting our air and water or communities. For that matter, they've rolled back dozens of Obama era environmental laws and regulations, many of which did protect air and water. So what's their goal here? How's that gonna work out?

DYKSTRA: Well, it's hard to say precisely from the administration's language, as you suggest from its actions maybe a little differently. Administrator Wheeler talked about how much cleaner our air is how much cleaner our water is, but he didn't point out that one of the main reasons that our air and water are cleaner would be the regulations that the White House and the EPA are now trying to roll back.

BASCOMB: All right, well, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: We have a very important 30th anniversary. This was actually last month in August, but it's worth mentioning. Bob Bullard is a professor at Texas Southern University. He's been called the founder of the environmental justice movement. And one of the reasons he can claim that title is a book and study that he released in August of 1990, called "Dumping in Dixie" was one of the first scholarly looks at how toxic waste dumps, how highly polluting factories, all tend to make their way into or near communities of color, or even poor white communities, both urban and rural throughout the United States.

Dr. Robert Bullard, professor at Texas Southern University, is known as one of the founders of the environmental justice movement. (Photo: Dave Brenner via University of Michigan School for the Environment, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah, boy, that's a problem that's been going on a long, long time. And I really timely reminder for us now, given the Black Lives Matter protests taking place across the country.

DYKSTRA: It is and it doesn't just refer to government inaction, or questionable action from big business, but even in the environmental community. Shortly after Bullard's "Dumping in Dixie" book came out 30 years ago, there was a letter sent to the CEOs of big environmental nonprofits criticizing the number of positions in authority in those organizations, held by people colour. With a few notable exceptions, that's still the case 30 years later, and the environmental movement is much open to criticism as being an elite white movement, and that pretty clearly would undermine its chances for success.

BASCOMB: All right, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news. That's ehn.org and daily climate.org. And we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay Bobby, thanks a lot, talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on these stories on the living on earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Read the letter requesting climate change discussion from 70 House Democrats to the Presidential Debates commission here

- Christian Science Monitor | “EPA to Focus on Clean-Ups, Economic Growth”

- Read more of Dr. Robert Bullard’s work here

[MUSIC: Toots & the Maytals, “Turn It Over” on Just Like That, by Toots Hibbert, Mango Records]

DOERING: Join Living on Earth for our next Good Reads on Earth virtual event. Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood will be talking with Sam Myers of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health about his new book, “Planetary Health: Protecting Nature to Protect Ourselves.” It's sure to be a lively and informative chat on Tuesday, September 15 at 7PM Eastern, live-streamed on Zoom and Facebook Live. We’ll ask smart questions and you can too! Learn more on the Living on Earth website loe.org and click "events" at the top of the page. See you then.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: New Zealand’s Kakapo

Kakapos are big, flightless birds that nevertheless manage to clamber up the trees of New Zealand’s forests. (Photo: © Jake Osborne)

BASCOMB: Islands are famously home to a huge diversity of endemic animals, found nowhere else on earth. Think of lemurs in Madagascar, Giant Tortoises in the Galapagos, or Kangaroos in Australia. And from New Zealand BirdNote’s Michael Stein has yet another example of an island producing a one-of-a-kind animal.

BirdNote®

New Zealand’s Kakapo

New Zealand is home to some very unusual birds—the kiwis for example. But none is more peculiar than the Kakapo. [Kakapo male call, https://www.doc.govt.nz/globalassets/documents/conservation/native-anima... The Kakapo is a kind of parrot, but one that doesn’t fly. At five pounds, it’s the world’s heaviest parrot. But being heavy and flightless doesn’t stop a Kakapo from getting up a tree. It uses its strong claws and beak to grip the bark and pull itself up. [Kakapo female call, https://www.doc.govt.nz/globalassets/documents/conservation/native-anima...

Kakapos are highly endangered but making a comeback. (Photo: © Jake Osborne)

Like many parrots, Kakapos are long-lived -- up to ninety years. Still, they’re highly endangered. These odd parrots evolved in an island world that lacked terrestrial predators. But all that changed when humans and their animals arrived. Now Kakapos are mostly consigned to a conservation recovery program on small islands that are free of predators. Things are looking up though. The Kakapo population has grown 70% in the past five years. Even though there are only about 200 Kakapos out there, that’s still more than at any time in the past seventy years. The next challenge? Find more safe habitat for the growing population of these one-of-a-kind parrots.

[Kakapo male call, https://www.doc.govt.nz/globalassets/documents/conservation/native-anima...

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

Editor: Ashley Ahearn

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Assistant Producer: Mark Bramhill

Bird sounds courtesy of New Zealand Government Department of Conservation, https://www.doc.govt.nz/nature/native-animals/birds/birds-a-z/kakapo/

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2020 BirdNote March 2020 Narrator: Michael Stein

ID# kakapo-01-2020-03-18 kakapo-01

[lots of information at this site: https://www.doc.govt.nz/kakapo-recovery]

https://www.doc.govt.nz/news/media-releases/2019/kakapo-population-reach...

https://www.google.com/amp/s/phys.org/news/2015-11-rimu-berry-game-chang...

https://www.birdnote.org/show/new-zealands-kakapo

BASCOMB: For pictures hop on over to the Living on Earth website, LOE dot Org

Related links:

- Find this story and more on the BirdNote® website

- Watch a short BBC video about “the cute and clumsy flightless parrot”

[MUSIC: Bonnie Raitt, “Slow Ride” on Luck Of the Draw, by B.Hayes/A.Pessis/L.J.McNally, Capitol Compact Disc]

Cutting Carbon for Healthier Kids

States participating in RGGI are expected to reduce their annual CO2 emissions from the power sector by 45% below 2005 levels by 2020, and by an additional 30% by 2030. (Photo: Neal Wellons, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: In 2009, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, known as RGGI, became the first mandatory market program in the US aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Ten states in the northeast and mid-Atlantic participate, and with the recent addition of Virginia, RGGI has now gained its first Southern state. Under the program, states set caps on carbon dioxide emissions from the power sector, and power plants purchase emissions allowances that are reinvested in energy efficiency and renewable energy. RGGI has already reduced emissions ahead of schedule but that’s not where the benefits end. A new study looks at the health improvements in children after living with reduced emissions for more than a decade. Dr. Frederica Perera is a lead author of this study, she’s a professor of environmental health sciences and Founding Director of the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health. Welcome back to Living on Earth!

PERERA: Thank you very much.

DOERING: So when you set out to evaluate the health effects of RGGI, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, what questions did you focus on?

PERERA: Well, first a bit of background. So climate policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel combustion also reduce air pollutants like fine respirable particles that are termed PM 2.5. Our research over more than 20 years, following groups of pregnant mothers and their children, has shown the harms of exposure even when the children are in utero, and that the developing fetus and young child are particularly vulnerable because they are developing so rapidly and they lack the biologic defenses that are operating in older individuals. And this is especially true in populations where poverty and environmental justice compound the effects and so this has been bad news that we and many other groups have been giving in terms of public health over these last decades, so here we had the opportunity to flip the question and ask what were the benefits to children of reducing air pollutants from a climate policy like RGGI, that mean Regional Greenhouse Gas initiative, which targeted CO2 emissions from coal and oil fired power plants in these nine northeastern states in the US, and at the same time, it brought down ambient levels of particulate matter. So this was a new idea because most health benefits assessments have mainly focused on adult mortality and hospitalizations. And they've admitted many of the benefits to children.

RGGI has been successful in reducing fine particulate matter emissions, as well as emissions of CO2 -- substantially improving children's health. (Photo: Kristy Faith, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: So, Professor, when you looked at the children's health benefits from RGGI, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative and these reduced health impacts, what kinds of benefits did you find? How many kids were potentially helped by RGGI?

PERERA: Well, we had good news. This was very nice for us to hear and I think nice for the public and for policymakers. So we consider the nine participating states. There were nine at the time and their neighboring states. And we found that between 2009 and 2014, RGGI has been successful in reducing fine particulate matter emissions, as well as emissions of CO2 and substantially improving children's health. There were an estimated 803 avoided cases of preterm birth, low birth weight, new asthma cases and autism. And the associated economic savings were estimated at hundreds of millions of dollars over these same years. And these benefits were in addition to those that had been estimated in terms of prevention of adult deaths through RGGI which were estimated at 300 to 830 avoided premature adult mortalities. These health benefits have signifigant economic value and they contradict that often cited false dichotomy between taking action on environment to protect public health and the economic costs of doing that. This is just another example of where the benefits really outweigh the costs. And we saw that with the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990, a 30 to one ratio of benefits to costs estimated for this current year 2020.

DOERING: Your study may actually underestimate the benefits to children's health from RGGI. Can you talk a little bit about why this is a conservative estimate?

In 2018, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy signed an executive order to have his state reenter the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. The state left RGGI in 2011 (Photo: Phil Murphy, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

PERERA: Well, this is a conservative estimate because the published cost of values per case of illness or impairment generally don't really include the long term lifelong consequences. That is a limitation in cognitive functioning or attentional problems or respiratory health problems. Those often persist into the adult years and effect the individual's ability to, to function to learn to earn, contribute to society. So those are not really incorporated into these cost functions. But there's a further limitation of the study that because the analysis was at the county level, rather than the neighborhood level, we weren't able to properly look at the distribution of benefits across racial and ethnic groups, and socio economic groups to assess equity within this program, and this is a goal in our future work. And it's important because we know that the hardest hit communities have been in the US and globally have been those communities that are low income and communities of color. They have suffered the most from air pollution and been most exposed had most of the impacts on health and that's true for children as well. And so, this is an issue that we really need to focus on. But what this study does do is put the face of children at the forefront on these policies. And this is important because as they are the most vulnerable among us, and their future is very much at stake. We need to be more protective of them, and in doing so will protect the entire population.

Dr. Frederica Perera is Professor of Environmental Health Sciences and the Director of the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. (Photo: Courtesy of Columbia University)

DOERING: So, Professor, what does it mean to you to be doing this research discovering the health benefits to children from this regional program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions? What's it like to know that hundreds of children's lives have been positively impacted?

PERERA: After so many years of doing research on the quote unquote, bad news, that is showing associations between pollution and harmful effects in children starting when they're in utero and in their early years, it was very positive for me and very hopeful to be able to see the results of this benefits analysis on estimated avoided cases of serious impairment and illness in children. And so that was heartening for me as a person as a researcher. And I hope we can do more of that kind of work in our field to be able to show the good news.

DOERING: Dr. Federica Perera is a professor of Environmental Health Sciences and founding director of the Columbia Center for Children's Environmental Health. Thank you so much, Dr. Perera.

PERERA: Thank you very much, Jenni. It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- About RGGI

- About Dr. Fredrica Perera

- Read the study on RGGI’s impact on children’s health

[MUSIC: Wiliam Coulter & Benjamin Verdery, “Drops of Brandy” on Song for Our Ancestors, Irish traditional, Solid Air Recordings]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Jay Feinstein, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. We bid a fond farewell to interns Anne Flaherty and Kori Suzuki -- thanks for your great work this summer!

BASCOMB: And we welcome Leah Jablo, Aaron Mok, and Casey Troost. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth