Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality In A Divided World

Air Date: Week of November 6, 2020

Melting glaciers in Iceland are changing locals’ relationship with the landscape. (Photo: Chris Goldberg, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

While the climate crisis poses grave risks for all it also increases the gap between the privileged and the marginalized. A new anthology called Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality in a Divided World is a collection of poems, short stories, essays, and reportage about the relationship between social inequality and the climate emergency. Host Aynsley O’Neill spoke with editor John Freeman about how fiction, nonfiction, and poetry are building a compelling literature on how climate change affects us all.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. While the climate crisis poses grave risks for all it also increases the gap between the privileged and the marginalized. Already, the global south is disproportionately affected by some consequences of the warming planet like food insecurity and nutrition deficiencies. Rising seas and increasingly intense natural disasters threaten the world's poorest people in a vicious cycle of devastating the already devastated. “Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality in a Divided World” is a collection of poems, short stories, essays, and reportage about the relationship between social inequality and the climate emergency. I’m joined now by the editor of the anthology, author John Freeman. John, welcome back to Living on Earth!

FREEMAN: So happy to be back!

O'NEILL: So first things first, what inspired you to collect all of these stories about climate change in the first place? And what's the biggest thing that you hope readers will take away from this book?

FREEMAN: Well, I feel, like as a lot of climatologists believe, our solutions to the climate crisis have to be collective, we can't recycle and eat less meat and drive our cars less to get our way out of the coming collapse of many of our ecosystems. We have to come up with large scale changes. And key to that is understanding that decisions we make in parts of the world that seem mildly, or even just a small amount of inconveniently affected, by climate change, can have an outsized effect on the other side of the globe. And that the climate crisis has been going on for decades now in parts of South Asia, in the Far East, in Sub Saharan Africa and Central America. So I wanted to put out a call to writers around the globe to say, okay, well, what does the climate crisis feel like where you are? And 35 of them came back with truly amazing stories of a huge variety. Some of them wrote fables. Some of them wrote reportage. Some of them wrote personal stories. Some of them wrote about rivers, some about glaciers. And I think what emerges is a kind of prismatic glimpse of what the climate crisis feels like around the globe now, and I think reading it, I hope readers will appreciate that we're all in this together. There is no higher ground, ultimately, for some of us. And actually, even if you could make that decision, would you?

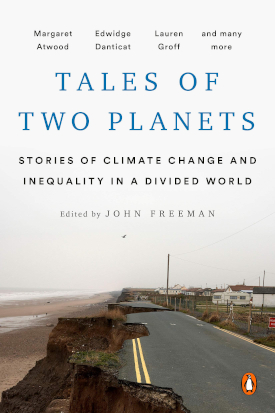

“Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality in a Divided World” is a collection of poems, short stories, essays, and reportage about the relationship between social inequality and the climate emergency. (Photo: Courtesy of Penguin Random House)

O'NEILL: For this book, you collaborated with writers all over the globe. You called it prismatic, and I feel like that's a really accurate statement. What was that like? And why do you think a global perspective on climate change is so important?

FREEMAN: It was exciting, to be honest, to be able to speak to people in all the different hemispheres about a problem that I feel deeply about, and I certainly feel is affecting many of our lives in America. But to hear from writers who are essentially living in the future, and to hear them describe the adaptations, they've had to make, the ways that their societies have changed. And to realize, you know, in this country, we've been living through a spasm of nationalism, in the middle of which, at the highest levels of government, there's been an incredibly damaging, and actually dangerous rhetoric about people coming to this country, from places that are no longer sustainable, or that are unsafe, and to realize that the US is not alone in that. I knew that academically, intellectually, but to read pieces from writers around the world, and to see that migration is a big and important subject within the climate crisis. And to see its effect on government, and lived experience. It made me feel actually hopeful. It made me realize that what we're living through is not exceptional, that it is part of a symptom of fear, a symptom of cynicism, and really an expression of of lack of hope. This feeling that there's not enough for everybody, when there is as long as we make some serious changes in how we live. And to see that writers around the world were willing to contribute to a collective project like this book, to move that dialogue forward. It ended up making me feel for the first time in this season of, you know, pandemic and political crisis and mendacity, made me feel hopeful.

O'NEILL: You mentioned COVID. Obviously, it's what's on all of our minds these days. How could it not be? The book explores the relationship between inequality and the environment, and how that all combines to affect our lives. How is this relationship especially relevant during the pandemic? And are there any stories that you wished were featured in the book about that?

Climate change can strengthen the catastrophic effects of natural disasters, leading to drastically altered landscapes. (Photo: Project LM, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

FREEMAN: I do in the sense that I live in New York City, and the death rates from COVID were drastically different based on what borough you lived in. And Queens was among the highest. That's where many of the people were dying in hospitals. And it was terrible to think that the lottery of your birth is determining, by and large, the lottery of your own death in the middle of this crisis. That's an unacceptable equation for any kind of functioning civic society. Because if there's anything a society agrees upon, it's the idea that we're better together. And, so in this book, there are lots of stories in which people do things because they have no other choice. So for example, there's a piece by Mariana Enriquez who's an Argentine short story writer. She lives in Buenos Aires, and there's a river that goes through the city called Rio Cholo, which is deeply polluted along its banks. It's where the slaughterhouses used to be. In fact, the river is called the River Slaughter. And many people that live there now have no other choice where to live. They come there from the north of Argentina, leaving where they have a cultural and psychological connection to the landscape, coming to a big city, and they end up in a place that’s slightly unhygienic and dangerous to their own health. And the politics of poverty and health are deeply connected to the politics of climate change. Because, you know, to go to the other extreme, we're watching as the world tilts towards billionaires and their favor, many of them are buying up huge properties and plots of land in New Zealand to create bolt holes in case the apocalypse arrives, as if it hasn't already arrived in some kind of slow motion form. And meanwhile, you know, many people cannot leave where they are, they don't have the choice. They're stuck with the reality of their landscape. There's another piece in here by Juan Miguel Alvarez, who's a Colombian journalist, and he describes people not leaving their homes in Colombia when they're being warned of impending landslides. And that's because they can't.

Dialogue about the climate crisis does have to absolutely engage with the structural inequalities of wealth, and the distribution of resources within societies. Otherwise, we're living in a fantasy because it is so much easier for someone who has too much to give up things, as someone who has very little to give up something that's connected to their daily life, that’s instrumental to it.

O'NEILL: One of the stories that is included in this is the short story "Survival" by Sayaka Murata, set in a dystopian futuristic version of Japan. And it's all about people who are trying to sort of buy themselves more time on Earth, increase their chances of survival. It deals with that story that you talk about, the lottery of your birth. Can you explain that story for our listeners, please?

FREEMAN: Really, it's a story of starcrossed lovers in which a couple meet and one of them has a very high survival rating in the 80% range. And then the woman who he fancies and who's really more the heroine of the story has a C minus, I believe. And what do you do in that circumstance? And I think what I love about Sayaka Murata's writing and in this story, in particular, is the climate crisis can seem, even in the middle of extreme weather events like we have now, as an abstract thing. But like all events, they become far less abstract when someone we care about is involved in them and there's nothing more involving than love. So, what would you do if you couldn't be with the person that you wanted to be with simply because of that sort of arbitrary lottery of survival? And that is the world that we live in, that if you were born in Calcutta, versus Cleveland, the chances of your survival in a climate crisis are very different. And I love the story, because it brings it to the most near and dear part of ourselves, which is the part that wants to give and receive love.

The frequency of natural disasters increases as the climate warms, affecting vulnerable communities first. (Photo: Joshua Stevens, NASA, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: I think it's especially impactful because when you look at it, it's dystopian, you think there's no way that anyone would be getting graded on their survival ability. But at the same time, you read more about it, and you read how it's connected to somebody’s lot in life when they're born, and how well they do in school and how well they do in college. And it really touches home in a way that it feels actually right around the corner.

FREEMAN: Yeah, I mean, think about how our schools are slotting kids into regular, remedial and honors programs. And those honors programs probably make it easier to get into colleges and get exposed to pre college admission testing and practicing. And you're absolutely right. We're living in a society that is highly structured. In this country, the United States, we've come up with mythologies that help us deal with the brutality of that structure. And one of those mythologies is the American dream. And we believe in the exceptional person, someone like Barack Obama, someone like Michael Jordan, who in spite of certain odds against their promotion in society rises above and becomes truly gracefully, profoundly beautiful at what they do. And we can't rely on the small numbers of people who do that to grade whether we're doing okay in equality. For every Michael Jordan or Michelle Obama, or you know, Sayaka Murata, where she to live in this country. There's going to be a lot of other people who aren't succeeding because of that structure.

O'NEILL: The story touches on the idea of buying time on Earth, making your situation and life better in order to just keep going as long as you can. To what extent does it feel like we are all buying time right now?

FREEMAN: Deeply. I mean, it's scary. I think there's a really profound disquiet because we're living in a world that feels currently in an interregnum. We're all in the middle of this pandemic. We don't know when it will end. It’s very hard to make plans. And then beyond that, there's not clear open skies. A lot of students that I work with as a teacher, they're terrified of their future and rightfully so. You know, when I was growing up in the 80s and 90s, you could presume that the world would be there until the end of hopefully a very long life. And now, you know, given the scale of weather events and the climate crisis strike difficult to imagine a stable future.

O'NEILL: So, one of the poems that really stood out to me in this was Margaret Atwood's "Tracking the Rain." Would you mind reading some of that out loud for us?

FREEMAN: Of course, it's a pleasure to.

This is called Tracking the Rain.

A mist of thin fat yellows the air. We breathe hot pudding. The leaves in the garden are crisp, like antique taffeta, the former garden. A touch and they shatter. Forget the lawn, the former lawn. Though the dandelions prosper. They've outlasted our flimsy hybrids. Their roots grip baked clay. All day it's pending, the rain. It gathers it witholds. We thumb our touchscreens, consulting the odds on the radar maps. Green puddles flow from west to east, vanishing before they hit the dot that's us. A stretched red dot like a comic book voice, devoid of words, like an upside down teardrop. That's where we're living now. Inside this dot, a color of a heated toaster. Inside this dry red bubble. We stand on the non lawn, arms outstretched mouths open. Will it be burn or drown? Though we've forgotten the incantation, the chant, the dance, we invoke a vertical ocean. Pure blue, pure water. Let it come down.

O'NEILL: And now for one of the biggest questions. What are we waiting for? What is this poem saying we're waiting for?

FREEMAN: I think it's saying we're waiting for some sort of divine intervention. You know, we've all sort of slipped into magical thinking. For the longest time humans looked up at the sky for some sort of sign, some sort of signal. Some sort of signal from the gods to say, this is what will happen, this is what to do. And that part of our brains, that part of our species, is deep. Even though we've lived through and created the enlightenment and all the ideas that came out of it, we still have this atavistic, antediluvian part of our minds that craves mythic direction. And yet, the thinking part of our minds, I think, knows very well that we've created this situation, we've created this drought, we've created this lack of rain. We've created this sort of digital world, which treats everything like a commodity. And so we have to be ready to take responsibility for the world we've created. There is no magical being coming to rescue us now. It has to be us.

For millions of people around the world, access to clean drinking water is scarce. (Photo: Finn Terman Frederiksen, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: The short story Dusk by Lauren Groff. It focuses on a life that maybe feels a little more close to home for many of us here in the United States: a middle-aged American housewife suffering from depression. She's someone in a position of environmental privilege, but she still feels powerless, not in control of her environment. Could you tell us a little bit about that story and why that perspective was something you felt should be included?

FREEMAN: Absolutely. I think no matter where we are in the world, maybe even Jeff Bezos feels this way. But I know a lot of us feel powerless to change the scale of what's coming for us. And so we deflect and we project. This character in Lauren Groff's story is living at home as a couple kids. Her husband works, she does not and raises the children. So, she starts paying attention to this neighbor next door who's a lot younger and has a lot more freedom and is flamboyantly, environmentally unfriendly. She keeps buying things on the internet and throwing the recyclable boxes in the trash. The character gets more and more agitated. And she latches on to this neighbor and what she's doing. And I think that's one of the symptoms of our time is when we feel powerless, and you can feel powerless if you have wealth, too, or if you have relative privileges like running water and a flushing toilet. In that environment, I think we tend to project and lash out. And it's a story about, in some ways, the breakdown of dialogue between generations as well. You know, for the younger character in the story, the future is abstract. It's over there, it's for old people to worry about. And plus, the old people have screwed it up anyway. Why should she change what she does, she's here to have a good time. And that's a very, in some ways, valid feeling. In a world that has been created by all the generations which have preceded the young, for them to look to us and say, "You know what, you created this mess, you know, could you help us a little bit? Or at least get out of my way while I try to have some fun before it implodes?"

O'NEILL: As you've mentioned, there's a multitude of different forms of writing in this. There's fiction, nonfiction, poetry, prose, essays, etc. How do those help us understand climate change? And what do you consider the power of literature on us as a species?

John Freeman is an American writer and literary critic. (Photo: Deborah Treisman)

FREEMAN: That's a good question. Imagine if every time you went to the movies, you only saw documentaries. And imagine if every time you went to the movies, you only saw documentaries about climate change. So yeah, maybe there was David Attenborough. And there's some other things, but after a while, you'd get, "Okay, I'm feeling a bit heavy here. Like just let me dream." And in some ways, that's hopefully how this book works. I mean, there are documentary pieces, you know reportage, that don't just tell you facts, but they tell them in the context of a person's life. And then there are pieces of fiction, which basically enchant you into dreaming about an alternate or similar world to ours. And then there are pieces like poetry, which you know, is intimate, it's closer, it's meant to be spoken aloud. And so it has an obvious an instant connection to the body, to the tongue, which is one of our strongest muscles, next to the heart. So I think when you put together a book about something as multifaceted and intense and ongoing as the climate crisis, why not bring all the different genres and all the different textures of thought and belief and and imagination that they can handle? Because if you only rely on facts and facts alone, I think a fact starts to be leached of the power of a fact after a while. A fact in order to be a fact, I think, has to be embedded in a story.

And then you can hold it.

O'NEILL: John Freeman is an author and he's the editor of Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality in a Divided World. Thank you, John.

FREEMAN: It's a pleasure.

Links

About the book Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality in a Divided World

More from author and editor John Freeman

Listen to our interview with John Freeman about his book of poetry, "The Park"

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth