November 6, 2020

Air Date: November 6, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Biden, Republicans and the Climate

View the page for this story

Some Republicans see opportunity for bipartisanship with a Democratic president, especially on the climate. Bob Inglis is a Republican and former US representative for South Carolina’s 4th Congressional District and he leads republicEn, a conservative organization focused on solving the climate crisis. He joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about climate solutions that can find support on both sides of the aisle if Congress remains divided amid a Biden presidency. (09:01)

Green Questions on the 2020 Ballot

/ Dharna NoorView the page for this story

Despite so much uncertainty during the 2020 presidential election, there have been some concrete answers on key environmental ballot questions across the country. Dharna Noor, staff writer for Earther, tells Host Aynsley O'Neill about the outcomes of the green ballot measures in the 2020 election. (05:31)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week on Beyond the Headlines, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Aynsley O’Neill talk about the numerous major hurricanes in the Atlantic this year. Then it’s on to Russia, which claims it will use carbon capture to offset emissions from its full-steam-ahead approach on gas and oil production. And in the history calendar, they look back to the wreck of an iron ore freighter in Lake Superior that inspired a hit song. (03:32)

Ice Hockey COVID Outbreaks

View the page for this story

With the onset of winter in the Northern Hemisphere come new concerns about what effect the reduction of sunlight and increased time spent indoors might have on coronavirus spread. Several outbreaks have occurred in connection with recreational and youth hockey, and researchers are rushing to pin down the role of air temperature and humidity in creating optimal conditions for contagion. For some advice about getting through winter safely, Host Steve Curwood caught up with pediatrician Aaron Bernstein, the interim director of Harvard’s Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment. (09:33)

Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality In A Divided World

View the page for this story

While the climate crisis poses grave risks for all it also increases the gap between the privileged and the marginalized. A new anthology called Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality in a Divided World is a collection of poems, short stories, essays, and reportage about the relationship between social inequality and the climate emergency. Host Aynsley O’Neill spoke with editor John Freeman about how fiction, nonfiction, and poetry are building a compelling literature on how climate change affects us all. (18:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

201106 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Aaron Bernstein, John Freeman, Bob Inglis, Dharna Noor

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

With a Democratic President, Some Republicans see opportunity for bipartisanship, especially on climate change.

INGLIS: There's some things to be done immediately I think Covid is the first thing to do. After that building back better with clean energy incentives but then building consensus for a broader climate package that goes deeper and worldwide.

CURWOOD: Also, Ohio voted red for president but its capital city Columbus went green on a referendum for renewable energy.

NOOR: Ballot initiatives like this can make a really big difference in shifting public opinion and also really offering residents cheaper rates, and more choices for renewable sources of energy. And, you know taking some power away from the private utility companies who have their interests in making a profit, not in protecting the planet and in people's pocketbooks.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Biden, Republicans and the Climate

The Biden-Harris plan for clean energy aims to reach net zero emissions by the year 2050. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0)

O'NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studio at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

As we go to broadcast all indications are that Joe Biden will be the next president of the United States, though President Trump has not yet conceded. Mr. Biden will take office in the midst of the surging coronavirus pandemic and the climate emergency. Both threats will require a bipartisan effort to address them. During the campaign Mr. Biden released a clean energy plan aimed at pushing the United States towards a 100% clean energy economy and achieving net-zero emissions by the year 2050. It’s an ambitious goal and here to talk about how Republicans and Democrats might work together to get there is Bob Inglis. He is a Republican and former US representative for South Carolina's 4th Congressional District and leads republicEn.org a conservative organization focused on solving the climate change crisis. Bob Inglis, welcome back to Living on Earth.

INGLIS: Good to be with you Steve. Thanks very much.

CURWOOD: So, who are some of the strongest Republican leaders, you think who will step forward and support President Joe Biden in moving forward a clean energy plan?

INGLIS: Yeah, you know, the ones that I look to mostly in the Senate would be Senator Braun of Indiana, Senator Romney, of Utah, in the House John Curtis in Utah. These are Republicans who, who have signaled a real willingness to talk about climate change and, of course, back to the Senate, Lisa Murkowski, very importantly, said recently that carbon pricing should be on the table, that was an important signal. So what it will take, I think, is Joe Biden actually reaching out to these Senators and House members. And I think there's a real shot at that, because of the humbler victory that he's won. He doesn't come in with my way or the highway, get out of the way, or the trains gonna roll over you. It's rather hey, folks, can we get it to the table and find a way to come together on climate change. And I also put in a lot of stock in Joe Biden's history in the US Senate, I think Joe Biden has a chance of being a nicer master of the Senate, a guy who has deep relationships there who understands the plays. Of course, he's got more help in the House with the Democratic majority so the senate is going to be where his attentions need to be paid.

The Biden-Harris campaign launched a transition website before President Trump conceded the presidential seat. (Photo: Screenshot of the Biden-Harris transition website)

CURWOOD: Now, the Biden administration is going to have an inbox that could probably reach to the top of the Washington Monument with just all kinds of things that need immediate attention, it would seem. How will the climate agenda, the climate protection agenda advanced in those circumstances? What do you think is the best move for the Biden administration to make right away regarding the climate? Except, of course for saying that we're back in in Paris, so the Paris Climate accord as he said he's going to do.

INGLIS: Yeah, that, of course, I think his thing he does first. I think, probably the next thing is build back better in the coronavirus times with infrastructure as it focuses on clean energy, he'll find bipartisan support for that. And then I hope what he sees is a real opportunity for a twofer especially to reward the progressive wing of his party with a pretty bold approach to climate change. And here's what I think that is it's to price carbon dioxide through a carbon tax. And then cut taxes on payroll so that you really are simultaneously addressing climate change, and income inequality. In the twofer for his progressive wing is did you see what I just did? We just gave low and moderate income earners, a 12.4% pay raise. So I hope that's what he does, it starts with dealing with clean energy incentives, but then goes worldwide with this kind of carbon tax. Whether you're conservative or progressive, everyone agrees that if there’s to be a carbon tax it needs to be border adjustable so that we apply the tax to imports coming into a very prized American market if it's coming from a country that doesn't have an equivalent price on carbon dioxide. Then the whole world's following, and now you got seven billion people seeing the true cost of the burning of fossil fuels, and the free enterprise system can deliver innovation. And of course, some of your listeners might be thinking, okay, Steve has on this guy that's very conservative, and he's talking in high octane Milton Friedman kind of terms, but they're thinking maybe sounds a little bit familiar. Well it might be the case, it's the same thing that Al Gore has been for, for about 30 years.

CURWOOD: Indeed. So what are the climate related infrastructure projects that you think that the Biden administration should quickly move forward with? And that will be not just palatable, but attractive to Republicans and Conservatives?

INGLIS: I think the electrification of the fleet with charging stations, he's mentioned that on the campaign trail, that's surely something that would help. More money for battery research. Remember we've had great breakthroughs in battery technology, but if we get even better batteries, it'll really make it so that batteries not natural gas, are the intermittency backup for wind and solar. Right now, natural gas is that backup, and that's the reality of our situation.

CURWOOD: A number of the folks in the senate are tied closely to coal, not necessarily by a party, of course, Mitch McConnell from Kentucky but also we have Joe Manchin from West Virginia and as the coal business has gone away, there's a huge pension problem there. How do you recommend President elect Biden deal with the need to bring along the coal states in a way that they will embrace dealing with climate disruption rather than continuing to fight it?

Bob Inglis was the U.S. Representative for South Carolina’s 4th District (R-SC, 1993-1999, and 2005-2011) and is currently the Executive Director of republicEn, where he promotes free enterprise action on climate change. (Photo Courtesy of republicEn)

INGLIS: Yeah, I think there's a great opportunity to bring America together on this. Because, you know, I think we can all agree that those miners gave us their lungs, in some cases have already given us their lives to provide energy for us. So we owe them something and I think as a conservative, that I owe them a buyout of their pensions. As their companies go bankrupt, and the pension liabilities fail, failed them, then we've got to step in and make those miners whole and that's a good use of some of the revenue from a carbon tax. And so what that creates is a political reality for people who used to be the representatives of coal country, is that those coal jobs clearly aren't coming back and now the coal companies are going under the pensions need to be paid and so it becomes an opportunity to say well, yeah, we can have climate action, if the climate action takes care of those miners. So I think it's a key constituency, particularly key for Mitch McConnell, presumably the Senate majority leader.

CURWOOD: And there's a similar situation regarding those communities that have been making their living drilling for oil, and then fracking natural gas.

INGLIS: Yeah, of course, oil and gas, maybe is a little bit further down the track here, where as those better batteries were just talking about come to be, you know, they're gonna be more at risk in the years ahead. That's why companies like BP are so focused on switching away from reliance on selling oil and gas. They're very prescient in that way, seeing what's coming at them and trying to figure out a way to continue to be in the energy business, maybe not just selling the same kind of energy.

CURWOOD: How do you deal with a number of elected officials who don't believe that there's a problem with the climate?

INGLIS: I think it's a dwindling number, thankfully. There is a cadre of folks who rejects all the data about climate change but it's a dwindling number. And one of the reasons it's dwindling, Steve, I think is a lot of them are having conversations with their children, grandchildren. You know, grandchild is coming home from State-U and they're saying, you know, Grandpa, or Grandma, what you're saying on the Senate floor, the House floor is not where they're teaching us State-U. And one of the terrible things about climate change is the realities are upon us. We are seeing the whites of its eyes now, we've got to take a shot, and it has to be a good shot.

CURWOOD: Bob Inglis was the US representative from South Carolina's 4th Congressional District. He's now executive director of republicEn.org. That's a group of conservatives who care about climate disruption. Bob, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

INGLIS: Great to be with you, Steve. Thanks.

Related links:

- ReSource | “'Death Spiral.' How A Carbon Tax Could End Some Coal Towns… Or Fund A New Future”

- Learn more about republicEn

- Learn more about Bob Inglis

[MUSIC: Epic Brass, “Carnival Of Venice” on Star Spangled Pops!, by H.L. Clarke, Ars Nova Records]

Green Questions on the 2020 Ballot

Throughout the country, the electorate cast their ballot, leading to some environmental wins on state and local referenda. (Photo: Megan Lee, VCU Capital News Service, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

O’NEILL: The uncertainty of the 2020 presidential election loomed large this year but several key environmental ballot measures were clearly decided on November 3rd. In Columbus, Ohio the electorate overwhelmingly voted to pledge the city to run on 100% renewable energy by 2022. Here to explain that decision and several other referenda across the country is Earther staff writer, Dharna Noor. Dharna welcome to Living on Earth!

NOOR: Thanks for having me.

O'NEILL: So, Ohio as a state, went red this year; voting for President Trump and having most of their House seats go to Republicans and they're a major fracking state but, Columbus, Ohio actually approved Issue 1 for Community Choice Aggregation. It passed in a landslide with 75% of Columbus locals voting yes. Could you tell us about that, please, Dharna?

NOOR: Yeah, I think this is a really exciting measure, because it will essentially give the government the power to buy electricity for residents of Columbus instead of utilities choosing. So, Columbus specifically is doing this with the goal of powering all homes and businesses with renewables by 2022, which is obviously a really ambitious timeline and one that's, you know, really in line with the best available science. And I think that's possible, because it's Columbus, Ohio. It's not, you know, the entire country or even entire state, Columbus's population is just 900,000-ish people. But I think that, you know still, ballot initiatives like this can make a really big difference in shifting public opinion, and also really like offering residents cheaper rates and more choices for renewable sources of energy and, you know, taking some power away from the private utility companies who have their interests in making a profit and not in, you know, protecting the planet and people's pocketbooks.

O'NEILL: And are there any similar ballot measures in any other parts of the country, Dharna?

NOOR: Yeah, actually another city, East Brunswick, New Jersey also passed Measure 4, which was another ballot initiative to create a Community Choice Aggregation program. Its timeline was a bit less ambitious. Their residents and businesses would have access to 100% renewables by 2030, but that's still a pretty ambitious timeline. And it is, you know, in line with what scientists say that we need to do in terms of changing our energy sources. So, still good.

O'NEILL: And let's move on over now to Louisiana, where an amendment that would have allowed property tax exemptions for the fossil fuel industry was voted down. Can you explain the goal of this amendment, and why blocking it was such a win for environmentalists?

Cameron Liquefied Natural Gas, as well as other fossil fuel and petrochemical companies, sponsored a ballot measure to pay discounted “cooperative endeavor agreements” instead of property taxes, seemingly forever. Louisiana voters struck down this proposed constitutional amendment. (Photo: MSU Lake Charles, U.S. Coast Guard, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

NOOR: Yes, I was really anxiously awaiting the results of this vote. And I was really, really heartened to see that Louisiana voters struck down Amendment 5. Essentially what this could have done is exempted the fossil fuel industry and the petrochemical industry from having to pay property taxes in the state of Louisiana forever. So, this would do so by essentially expanding the state's constitution to let local governments start what they're calling "cooperative endeavor agreements" or "payments in lieu of taxes" with companies, which would allow companies to stop paying taxes and instead make these comparatively really small payments to the state government. And the main lobbying force behind that measure is Cameron, which is this liquefied natural gas firm. Cameron, like Cameron Parish, the area that saw a really dangerous petrochemical leak when hurricanes whirred through the state earlier this year.

O'NEILL: And so what would the impact have been if this ballot measure had passed?

NOOR: So again, the main lobbying force behind the measure was this liquefied natural gas company, Cameron. And just for instance, based on their agreement with the state last year, they paid $38,000 in taxes, which seems like a lot. But if they'd had to pay their full taxes, they would have paid $220 million. So it's pretty clear that these "payment in lieu of taxes" agreements just allow these polluting companies to get away with paying far less, and behave as though they're doing something really great for the people of Louisiana. If this measure had passed, their agreement could have lasted forever, rather than expiring next year. And, you know, it could be expanded so that many, many other companies could obtain the same kinds of agreements. And that's really important because petrochemical companies and natural gas companies are really, really popular in Louisiana, it's home to multiple petrochemical hubs.

O'NEILL: So Dharna, are there any other ballot measures that you've been keeping your eye on?

Dharna Noor is a staff writer for Earther, from Gizmodo. (Photo: Courtesy of Dharna Noor)

NOOR: I guess one that's, you know, a little anticlimactic, but good is that Question 6 in Nevada passed. That's going to require the state's utilities to get 50% of their electricity from renewables by 2030. The state actually passed this measure in 2018. But in Nevada, voters have to pass amendments in two election cycles. I think that, you know, this is, as I said, a bit anticlimactic and really shows, you know, sort of the importance of local measures, but also sort of the need for more ambitious ones. 50% by 2030 is not really a quick enough timeline, according to reams of research from you know, the top climate scientists. By then we really need to be moving toward 100% renewable energy. Hopefully, this will be a good opening for folks to push for more ambitious proposals. And sadly, you know, 50% by 2030 is actually more ambitious than many, many places around the country. But hopefully in coming election cycles, we will take this far, far more seriously.

O'NEILL: Dharna Noor is a staff writer at Earther, from Gizmodo. Dharna, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

NOOR: Thank you so much.

Related links:

- Earther | “The Most Important Climate Ballot Initiatives to Watch on Election Day”

- Dharna Noor on Twitter

- The Columbus Dispatch | “Columbus Voters Approve Green-Energy Aggregation Plan”

- Insider NJ | “East Brunswick Voters Back Bold Clean Energy Ballot Question”

- WRKF 89.3 | “Louisiana Votes No on Amendment 5”

- Vox | “Nevada Voters Seal Renewable Energy Goals in Their State Constitution”

- More from Dharna Noor

[MUSIC: Epic Brass, “Solace” on Star Spangled Pops!, by S. Joplin, Ars Nova Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – As the northern winter approaches and Covid-19 cases spike we have some tips for staying safe.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Christian McBride, Nicholas Payton, Mark Whitfield “Fingerpainting” on Fingerpainting: The Music Of Herbie Hancock, The Verve Music Group]

Beyond the Headlines

National Guard Soldiers distributing water around Mississippi communities after hurricane Zeta. (Photo: Danielle Thomas, U.S. National Guard, Flickr)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

O’NEILL: It's time now for a look Beyond the Headlines with Peter Dykstra. He's an editor with environmental health news that's ehn.org and daily climate.org. He should be on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter. How are you doing?

Hurricane Eta flooded homes from Panama to Guatemala. At the time of this publication, 57 people have been reported dead. (Photo: Screen capture from NASA, public domain)

DYKSTRA: Hi, Aynsley. I'm doing all right. We had a slight brush here in Atlanta with one of those Greek alphabet, hurricanes, hurricane Zeta passed by this past week, power was out for a big part of the city, almost out in my building, but we made it through. And let's talk about the rest of the hurricanes down here, starting in Asia with typhoon Goni, one of the biggest storms on record, although it missed the big population areas in the Philippines. A death toll but a relatively low death toll, just to show that it's not just the Atlantic, where we're setting records, but elsewhere in the world where some of those frequent severe storms predicted with climate change are a reality. Hurricane Eta was blowing through Central America this week. We've never been farther in the Greek alphabet. The only time we've gotten this far was 15 years ago, 2005, the year of Katrina, and Rita, New Orleans and all of Louisiana took a beating this year, with five named storms making landfall so far and nearly another full month to go. The Atlantic hurricane season is considered to be on until November 30.

O’NEILL: Yeah, it's never a good sign when we've moved through the Roman alphabet. And now we're on to the Greeks. But tell us, Peter, what else do you have?

Hurricane Eta hit Nicaragua and then moved to neighboring Honduras and Guatemala. This picture is of a father and son leaving their homes in Guatemala after it was flooded from the Category 4 hurricane. (Photo: Ennoti, Flickr, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: Oh, yeah, Russia just said forget about it to cutting back on it's economically crucial oil and gas production. They say they're gonna keep going for decades, they've ruled out cutting back substantially natural gas, and natural gas exports to the EU are a huge part of the Russian economy. They say they're going to pursue carbon capture, no nation has been able to make substantial progress on that to date. And it's a stark contrast to other economic powers on the Pacific Rim. Both South Korea and Japan are right now struggling and pledging to make their way to being carbon neutral within the next 30 years.

O’NEILL: All right, then, Peter, what do you have from the history books for us?

DYKSTRA: 1975, November 10th to be exact. I was a freshman in college. There wasn't much made a bet at the time, but on November 10, an iron ore freighter called the Edmund Fitzgerald wrecked and sank in a storm in Lake Superior.

O’NEILL: Well, I'm not gonna lie, Peter, I was definitely not a freshman in college in 1975. But tell me a little bit more about this wreck.

The Edmund Fitzgerald was a freight ship that sank in the Great Lakes on November 10, 1975. (Photo: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, you had 20 years to go before you were even a fetus. In 1975 Edmund Fitzgerald made regular runs from Duluth, Minnesota, where iron ore was offloaded from the Iron Range in Minnesota, shipped across the lakes to the steel mills in Cleveland never made it even halfway to Cleveland. It got caught in an early winter storm, it sank, the crew died and a year later it was a hit song by Gordon Lightfoot that made it as the top 40 hit from the Canadian folk singer. That didn't happen very often, either.

O’NEILL: All right. Well, thank you. Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right. Thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

O’NEILL: And there's more on these stories on living on earth website. That's loe.org

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “‘Zeta Cuts Out Power to Millions Across the South Leaves Six Dead”

- The Washington Post | “‘Hurricane Eta Exploded After Hitting Nicaragua and we May Never Know How Strong It Was”

- The Guardian | “‘Russia Rules Out Cutting Out Fossil Fuel Production in the Next Few Decades”

- Sea Grant Michigan | “‘The Storm that Sunk the Edmund Fitzgerald”

- Listen to Gordon Lightfoot’s Song About the Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald

[MUSIC: Gordon Lightfoot, “The Wreck Of the Edmund Fitzgerald” on Summertime Dream, by Gordon Lightfoot, Reprise Record

Ice Hockey COVID Outbreaks

Getting a flu shot may be particularly important this year, as coronavirus stresses medical resources. (Photo: Phillip Jeffrey, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: The Covid 19 pandemic is accelerating in the northern hemisphere as colder weather settles in. Hospitals and health care workers are struggling in many communities, especially in the US where the daily tally of new cases is spiking at record levels. The trend is expected to continue as more activities shift indoors. There is much that science still has to learn about Covid-19, such as why indoor recreational ice hockey has been associated with outbreaks in several states, not just in the north but also in Florida, where about a dozen people got Covid 19 after a game at a hockey rink in Tampa Bay. For some advice for getting through winter safely we turn now to Dr. Aaron Bernstein, he’s Pediatrician at Boston Children’s Hospital and interim director of Harvard’s Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Ari!

BERNSTEIN: Great to be with you, Steve.

CURWOOD: So we're seeing coronavirus outbreaks in connection with indoor ice hockey practices to a greater extent than what's been seen in other sports and activities. Walk us through in basic terms, what about the virus might make it more dangerous for these cold weather sports and as the colder weather approaches?

BERNSTEIN: Well, I think we're still digging into what's going on in the skating rinks. But the best clues we have right now is that transmission may not be happening as much on the ice, but may be happening off the ice in locker rooms or on the bench when people may take off protective gear or sit too close with each other. We don't really know. But it's pretty clear that since there have been outbreaks in multiple states associated with hockey playing, that there is something about it that matters. But we mostly see in in other indoor settings transmission happening when you've got people sticking around each other for long periods of time. And so that makes locker rooms, for example, a prime suspect.

Recreational hockey seems to be a high-risk activity for coronavirus, but the exact reason is still under investigation. (Photo: Pointnshoot, Flickr, CC by 2.0)

CURWOOD: How fair is it to assume that the locker rooms are also really pretty cold adjacent to the ice and in the building that's trying to keep the ice there?

BERNSTEIN: We do know a couple of things. I mean, what's clear is that sunlight is really good at inactivating the virus. So, you know, ice skating rinks are not in a lot of sunlight, whether it's the ice or the locker room, that's true, obviously, of any indoor environment. So the ultraviolet piece seems to be a pretty strong signal in terms of temperature, and humidity, it gets kind of messy. And that's one of the reasons why the winter people are concerned because particularly here in the Northern Hemisphere, there's a lot less ultraviolet radiation hitting us from the sun.

CURWOOD: So as we move into winter, of course, historically, the influenza virus seems to do much better in the winter. What parallels can we draw between the influenza virus and the novel coronavirus in terms of transmission in this cold part of the year?

BERNSTEIN: Well, I think the big deal in winter transmission of viruses that are transmitted by you know, coughs and sneezes, and the droplets they can leave on surfaces, is that people tend to gather indoors a lot more in the winter. That's a risk factor for any of these viruses. And so when I think about the winter, I do think we need to pay close attention to places where we're asking people to congregate, and being careful about the appropriate precautions to ensure that we're not having, you know, unnecessary spread. I mean, it's, we're breaking records in transmission as we speak and there's a great risk that this virus can spread through the winter, the idea has been floated that herd immunity will protect this is reckless and dangerous. And we can do a tremendous amount even now, to reduce, we can't eliminate at this point, but we can reduce the amount of spread through the basic measures that leaders in public health have been talking about for a long time now.

CURWOOD: What's the best thinking about how communities can protect their most vulnerable members, during this time of rising numbers of these cases, rising exposure, apparently better conditions for the virus?

BERNSTEIN: Yeah, you know, it probably is sounding completely boring and beating a dead horse. But it's the same dull stuff that folks have been talking about for a long time, it's wearing a mask, it's washing your hands, it's keeping physical distance. And those measures can have a dramatic effect upon the spread of disease. And you know, there are people anguishing a lot right now about what's safe in terms of, you know, should we go to place a, b, or c, and that is entirely dependent upon the spread of the disease in the community. If you're living in a place, you know, right now, we have tremendous case burdens in the upper Midwest, in particular, you know, the risks of doing the things that people are thinking about doing are much higher when you have higher case counts in the community, even with those protective measures. But you know, I think a lot of people, including folks like Tony Fauci, and other public health leaders have strongly advised people to not gather in person, because the risks are growing so great, because the reality is that we have more cases today in the country than almost any other time. And the signs are this winter, it may not get better quickly.

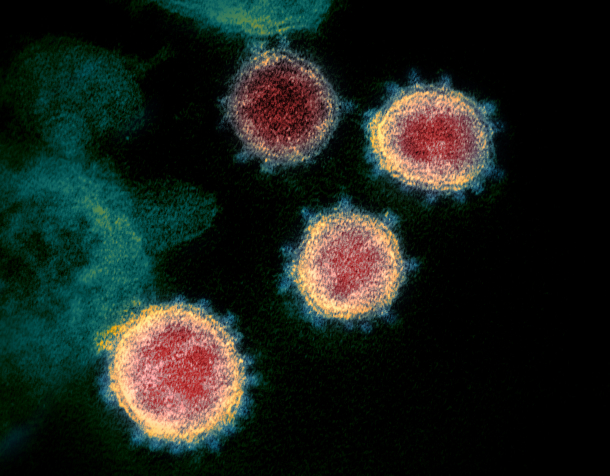

The novel coronavirus seems to degrade quickly when exposed to UV light, and seems to be more transmissible at particular levels of heat and humidity. (Photo: NIAID-RML, Wikimedia Commons, CC by 2.0)

CURWOOD: So know, to what extent to things change if a vaccine becomes widely available in the next few months.

BERNSTEIN: Yeah, well, I think the first thing to acknowledge is that we hopefully will have an effective vaccine in the next few months. But it's clear that that most people will not have access to that well into 2021. And so we can't really bank on that as a way to get us out of this mess in the next few months of this year. And probably not in the first few months of the next year. We also have an issue in which there are many people in the country who don't want to vaccinate. And that's, you know, a real challenge because again, the risk isn't just to the individuals who don't vaccinate, it's to the people who live in their communities. And, you know, it's as a pediatrician, you know, we deal with this concern all the time, which was we don't have many, but there are some families who do not want to vaccinate their children or don't want to vaccinate on the usual schedule or want vaccine one versus vaccine two. And these are obviously concerns for the child. We don't give these vaccines because the diseases aren't a problem we give them because the diseases are a big problem. But it's very much a concern for the people they live with. I have more stories than I would ever want to know about a family who did not vaccinate, their children got sick and their children were okay, but they infected someone else's children. And those children were not okay. And who really wants to live with that sense of, you know, grief, that we have a vaccine for preventable diseases and that, you know, by not getting ourselves vaccinated, we put other people at risk who are, you know, don't do as well. And I think that's very much the case with Coronavirus. You know, we see now high rates of transmission among people who are younger, who tend to be okay. But those infections don't limit themselves to geographic borders, or political parties or religions or anything. So we just have to remember that part of our action here is not just for ourselves, it's for the people who live in our country and in, you know, our communities. And beyond that, you know, it's making sure that people get their flu vaccines, right. So people don't see those two connected to they're actually very much connected. So we're going to have a flu epidemic this year, like we do every year, we can hope that it is not a bad flu year. We don't know yet. But it's gonna come and there's a vaccine. And the reason they're connected is that we know we're going to have a tremendous burden of coronavirus cases we already see in many states hospital beds, essentially being at max capacity. Well, that's what happens in a bad flu season. So if you take the current coronavirus season, and you add to it even a mild flu season, there are no hospital beds for people to go into. We can do a lot more now today than we could at the start of this virus to keep people who get sick enough to be hospitalized from getting severely ill. But if we're picking and choosing hospital beds and don't have hospital beds, it makes our lives as healthcare providers majorly more difficult. So I you know, there are a lot of people who don't want to get vaccinated for the flu because they think it's not that bad, or they think the flu vaccine doesn't work. And neither of those things are true. And so this is really an issue of protecting healthcare resources, not to mention protecting yourself and your family. And again, the flu is a major factor in severe illness and people who are older, so in one of the populations that's really at risk from coronavirus are also really at risk for their flu.

Dr. Aaron Bernstein works as a pediatrician, but also coordinates research on the intersection of the climate, air pollution, and human health. (Photo: Courtesy of Aaron Bernstein)

And so, you know, I'm, you know, I'm not over 65 and I have to get vaccinated, so I work in health care. But even if I didn't, I would recognize that if I want to protect my family, I should be getting vaccinated against the flu to protect people who are older than me, my family members who may have cancer, my family members who may be pregnant. You know, think about it. If you have a family member who's pregnant, they often need to go to a hospital. Do you really want them to go to a hospital in which the hospital is overwhelmed with preventable influenza infections? No. Obviously. So that's how these things tie together pretty quickly.

CURWOOD: Ari Bernstein is a pediatrician at Children's Hospital in Boston and directs the Climate Health Program at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. Dr. Bernstein, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

BERNSTEIN: Thanks for having me, Steve.

Related links:

- Read the CDC report on an outbreak at a Tampa Bay Hockey game

- Read more about Massachusetts' decision to shut down youth hockey until more data could be gathered

- Learn why influenza virus cases surge in winter

- Learn more about flu and cold weather

- Read the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services report on the link between healthy forests and pandemic prevention

[MUSIC: Margot Chamberlain, “Bridget Cruise/Deirdre” on Golden Threads, by Turlough O’Carolan/Tom Megan, self-published]

O’NEILL: Coming up – climate disruption as a threat multiplier for marginalized people. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: David Buchbinder, “Calliope” on Walk To the Sea, by David Buchbinder, Tzadik]

Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality In A Divided World

Melting glaciers in Iceland are changing locals’ relationship with the landscape. (Photo: Chris Goldberg, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. While the climate crisis poses grave risks for all it also increases the gap between the privileged and the marginalized. Already, the global south is disproportionately affected by some consequences of the warming planet like food insecurity and nutrition deficiencies. Rising seas and increasingly intense natural disasters threaten the world's poorest people in a vicious cycle of devastating the already devastated. “Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality in a Divided World” is a collection of poems, short stories, essays, and reportage about the relationship between social inequality and the climate emergency. I’m joined now by the editor of the anthology, author John Freeman. John, welcome back to Living on Earth!

FREEMAN: So happy to be back!

O'NEILL: So first things first, what inspired you to collect all of these stories about climate change in the first place? And what's the biggest thing that you hope readers will take away from this book?

FREEMAN: Well, I feel, like as a lot of climatologists believe, our solutions to the climate crisis have to be collective, we can't recycle and eat less meat and drive our cars less to get our way out of the coming collapse of many of our ecosystems. We have to come up with large scale changes. And key to that is understanding that decisions we make in parts of the world that seem mildly, or even just a small amount of inconveniently affected, by climate change, can have an outsized effect on the other side of the globe. And that the climate crisis has been going on for decades now in parts of South Asia, in the Far East, in Sub Saharan Africa and Central America. So I wanted to put out a call to writers around the globe to say, okay, well, what does the climate crisis feel like where you are? And 35 of them came back with truly amazing stories of a huge variety. Some of them wrote fables. Some of them wrote reportage. Some of them wrote personal stories. Some of them wrote about rivers, some about glaciers. And I think what emerges is a kind of prismatic glimpse of what the climate crisis feels like around the globe now, and I think reading it, I hope readers will appreciate that we're all in this together. There is no higher ground, ultimately, for some of us. And actually, even if you could make that decision, would you?

“Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality in a Divided World” is a collection of poems, short stories, essays, and reportage about the relationship between social inequality and the climate emergency. (Photo: Courtesy of Penguin Random House)

O'NEILL: For this book, you collaborated with writers all over the globe. You called it prismatic, and I feel like that's a really accurate statement. What was that like? And why do you think a global perspective on climate change is so important?

FREEMAN: It was exciting, to be honest, to be able to speak to people in all the different hemispheres about a problem that I feel deeply about, and I certainly feel is affecting many of our lives in America. But to hear from writers who are essentially living in the future, and to hear them describe the adaptations, they've had to make, the ways that their societies have changed. And to realize, you know, in this country, we've been living through a spasm of nationalism, in the middle of which, at the highest levels of government, there's been an incredibly damaging, and actually dangerous rhetoric about people coming to this country, from places that are no longer sustainable, or that are unsafe, and to realize that the US is not alone in that. I knew that academically, intellectually, but to read pieces from writers around the world, and to see that migration is a big and important subject within the climate crisis. And to see its effect on government, and lived experience. It made me feel actually hopeful. It made me realize that what we're living through is not exceptional, that it is part of a symptom of fear, a symptom of cynicism, and really an expression of of lack of hope. This feeling that there's not enough for everybody, when there is as long as we make some serious changes in how we live. And to see that writers around the world were willing to contribute to a collective project like this book, to move that dialogue forward. It ended up making me feel for the first time in this season of, you know, pandemic and political crisis and mendacity, made me feel hopeful.

O'NEILL: You mentioned COVID. Obviously, it's what's on all of our minds these days. How could it not be? The book explores the relationship between inequality and the environment, and how that all combines to affect our lives. How is this relationship especially relevant during the pandemic? And are there any stories that you wished were featured in the book about that?

Climate change can strengthen the catastrophic effects of natural disasters, leading to drastically altered landscapes. (Photo: Project LM, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

FREEMAN: I do in the sense that I live in New York City, and the death rates from COVID were drastically different based on what borough you lived in. And Queens was among the highest. That's where many of the people were dying in hospitals. And it was terrible to think that the lottery of your birth is determining, by and large, the lottery of your own death in the middle of this crisis. That's an unacceptable equation for any kind of functioning civic society. Because if there's anything a society agrees upon, it's the idea that we're better together. And, so in this book, there are lots of stories in which people do things because they have no other choice. So for example, there's a piece by Mariana Enriquez who's an Argentine short story writer. She lives in Buenos Aires, and there's a river that goes through the city called Rio Cholo, which is deeply polluted along its banks. It's where the slaughterhouses used to be. In fact, the river is called the River Slaughter. And many people that live there now have no other choice where to live. They come there from the north of Argentina, leaving where they have a cultural and psychological connection to the landscape, coming to a big city, and they end up in a place that’s slightly unhygienic and dangerous to their own health. And the politics of poverty and health are deeply connected to the politics of climate change. Because, you know, to go to the other extreme, we're watching as the world tilts towards billionaires and their favor, many of them are buying up huge properties and plots of land in New Zealand to create bolt holes in case the apocalypse arrives, as if it hasn't already arrived in some kind of slow motion form. And meanwhile, you know, many people cannot leave where they are, they don't have the choice. They're stuck with the reality of their landscape. There's another piece in here by Juan Miguel Alvarez, who's a Colombian journalist, and he describes people not leaving their homes in Colombia when they're being warned of impending landslides. And that's because they can't.

Dialogue about the climate crisis does have to absolutely engage with the structural inequalities of wealth, and the distribution of resources within societies. Otherwise, we're living in a fantasy because it is so much easier for someone who has too much to give up things, as someone who has very little to give up something that's connected to their daily life, that’s instrumental to it.

O'NEILL: One of the stories that is included in this is the short story "Survival" by Sayaka Murata, set in a dystopian futuristic version of Japan. And it's all about people who are trying to sort of buy themselves more time on Earth, increase their chances of survival. It deals with that story that you talk about, the lottery of your birth. Can you explain that story for our listeners, please?

FREEMAN: Really, it's a story of starcrossed lovers in which a couple meet and one of them has a very high survival rating in the 80% range. And then the woman who he fancies and who's really more the heroine of the story has a C minus, I believe. And what do you do in that circumstance? And I think what I love about Sayaka Murata's writing and in this story, in particular, is the climate crisis can seem, even in the middle of extreme weather events like we have now, as an abstract thing. But like all events, they become far less abstract when someone we care about is involved in them and there's nothing more involving than love. So, what would you do if you couldn't be with the person that you wanted to be with simply because of that sort of arbitrary lottery of survival? And that is the world that we live in, that if you were born in Calcutta, versus Cleveland, the chances of your survival in a climate crisis are very different. And I love the story, because it brings it to the most near and dear part of ourselves, which is the part that wants to give and receive love.

The frequency of natural disasters increases as the climate warms, affecting vulnerable communities first. (Photo: Joshua Stevens, NASA, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: I think it's especially impactful because when you look at it, it's dystopian, you think there's no way that anyone would be getting graded on their survival ability. But at the same time, you read more about it, and you read how it's connected to somebody’s lot in life when they're born, and how well they do in school and how well they do in college. And it really touches home in a way that it feels actually right around the corner.

FREEMAN: Yeah, I mean, think about how our schools are slotting kids into regular, remedial and honors programs. And those honors programs probably make it easier to get into colleges and get exposed to pre college admission testing and practicing. And you're absolutely right. We're living in a society that is highly structured. In this country, the United States, we've come up with mythologies that help us deal with the brutality of that structure. And one of those mythologies is the American dream. And we believe in the exceptional person, someone like Barack Obama, someone like Michael Jordan, who in spite of certain odds against their promotion in society rises above and becomes truly gracefully, profoundly beautiful at what they do. And we can't rely on the small numbers of people who do that to grade whether we're doing okay in equality. For every Michael Jordan or Michelle Obama, or you know, Sayaka Murata, where she to live in this country. There's going to be a lot of other people who aren't succeeding because of that structure.

O'NEILL: The story touches on the idea of buying time on Earth, making your situation and life better in order to just keep going as long as you can. To what extent does it feel like we are all buying time right now?

FREEMAN: Deeply. I mean, it's scary. I think there's a really profound disquiet because we're living in a world that feels currently in an interregnum. We're all in the middle of this pandemic. We don't know when it will end. It’s very hard to make plans. And then beyond that, there's not clear open skies. A lot of students that I work with as a teacher, they're terrified of their future and rightfully so. You know, when I was growing up in the 80s and 90s, you could presume that the world would be there until the end of hopefully a very long life. And now, you know, given the scale of weather events and the climate crisis strike difficult to imagine a stable future.

O'NEILL: So, one of the poems that really stood out to me in this was Margaret Atwood's "Tracking the Rain." Would you mind reading some of that out loud for us?

FREEMAN: Of course, it's a pleasure to.

This is called Tracking the Rain.

A mist of thin fat yellows the air. We breathe hot pudding. The leaves in the garden are crisp, like antique taffeta, the former garden. A touch and they shatter. Forget the lawn, the former lawn. Though the dandelions prosper. They've outlasted our flimsy hybrids. Their roots grip baked clay. All day it's pending, the rain. It gathers it witholds. We thumb our touchscreens, consulting the odds on the radar maps. Green puddles flow from west to east, vanishing before they hit the dot that's us. A stretched red dot like a comic book voice, devoid of words, like an upside down teardrop. That's where we're living now. Inside this dot, a color of a heated toaster. Inside this dry red bubble. We stand on the non lawn, arms outstretched mouths open. Will it be burn or drown? Though we've forgotten the incantation, the chant, the dance, we invoke a vertical ocean. Pure blue, pure water. Let it come down.

O'NEILL: And now for one of the biggest questions. What are we waiting for? What is this poem saying we're waiting for?

FREEMAN: I think it's saying we're waiting for some sort of divine intervention. You know, we've all sort of slipped into magical thinking. For the longest time humans looked up at the sky for some sort of sign, some sort of signal. Some sort of signal from the gods to say, this is what will happen, this is what to do. And that part of our brains, that part of our species, is deep. Even though we've lived through and created the enlightenment and all the ideas that came out of it, we still have this atavistic, antediluvian part of our minds that craves mythic direction. And yet, the thinking part of our minds, I think, knows very well that we've created this situation, we've created this drought, we've created this lack of rain. We've created this sort of digital world, which treats everything like a commodity. And so we have to be ready to take responsibility for the world we've created. There is no magical being coming to rescue us now. It has to be us.

For millions of people around the world, access to clean drinking water is scarce. (Photo: Finn Terman Frederiksen, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: The short story Dusk by Lauren Groff. It focuses on a life that maybe feels a little more close to home for many of us here in the United States: a middle-aged American housewife suffering from depression. She's someone in a position of environmental privilege, but she still feels powerless, not in control of her environment. Could you tell us a little bit about that story and why that perspective was something you felt should be included?

FREEMAN: Absolutely. I think no matter where we are in the world, maybe even Jeff Bezos feels this way. But I know a lot of us feel powerless to change the scale of what's coming for us. And so we deflect and we project. This character in Lauren Groff's story is living at home as a couple kids. Her husband works, she does not and raises the children. So, she starts paying attention to this neighbor next door who's a lot younger and has a lot more freedom and is flamboyantly, environmentally unfriendly. She keeps buying things on the internet and throwing the recyclable boxes in the trash. The character gets more and more agitated. And she latches on to this neighbor and what she's doing. And I think that's one of the symptoms of our time is when we feel powerless, and you can feel powerless if you have wealth, too, or if you have relative privileges like running water and a flushing toilet. In that environment, I think we tend to project and lash out. And it's a story about, in some ways, the breakdown of dialogue between generations as well. You know, for the younger character in the story, the future is abstract. It's over there, it's for old people to worry about. And plus, the old people have screwed it up anyway. Why should she change what she does, she's here to have a good time. And that's a very, in some ways, valid feeling. In a world that has been created by all the generations which have preceded the young, for them to look to us and say, "You know what, you created this mess, you know, could you help us a little bit? Or at least get out of my way while I try to have some fun before it implodes?"

O'NEILL: As you've mentioned, there's a multitude of different forms of writing in this. There's fiction, nonfiction, poetry, prose, essays, etc. How do those help us understand climate change? And what do you consider the power of literature on us as a species?

John Freeman is an American writer and literary critic. (Photo: Deborah Treisman)

FREEMAN: That's a good question. Imagine if every time you went to the movies, you only saw documentaries. And imagine if every time you went to the movies, you only saw documentaries about climate change. So yeah, maybe there was David Attenborough. And there's some other things, but after a while, you'd get, "Okay, I'm feeling a bit heavy here. Like just let me dream." And in some ways, that's hopefully how this book works. I mean, there are documentary pieces, you know reportage, that don't just tell you facts, but they tell them in the context of a person's life. And then there are pieces of fiction, which basically enchant you into dreaming about an alternate or similar world to ours. And then there are pieces like poetry, which you know, is intimate, it's closer, it's meant to be spoken aloud. And so it has an obvious an instant connection to the body, to the tongue, which is one of our strongest muscles, next to the heart. So I think when you put together a book about something as multifaceted and intense and ongoing as the climate crisis, why not bring all the different genres and all the different textures of thought and belief and and imagination that they can handle? Because if you only rely on facts and facts alone, I think a fact starts to be leached of the power of a fact after a while. A fact in order to be a fact, I think, has to be embedded in a story.

And then you can hold it.

O'NEILL: John Freeman is an author and he's the editor of Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality in a Divided World. Thank you, John.

FREEMAN: It's a pleasure.

Related links:

- About the book Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality in a Divided World

- More from author and editor John Freeman

- Listen to our interview with John Freeman about his book of poetry, "The Park"

[MUSIC: Margot Chamberlain, “Pentatonic Improvisation” on Golden Thread, by Margot Chamberlain, self-published]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth – tiny bits of plastic are being applied to cropland with troubling results.

There’s been a suite of recent studies that show changes to soil’s ability to retain water, truncated plant growth and they found impacts in earthworms.

CURWOOD: Tune in to learn about the growing problem of polyester fibers and other microplastic particles being applied to farmland, That’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Christian McBride, Roy Hargrove, and Stephen Scott “Yardbird Suite” on Parker’s Mood, The Verve Music Group]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Leah Jablo, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aaron Mok, Jake Rego, Casey Troost, and Jolanda Omari.

O’NEILL: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth