Sustainable Thanksgiving Fare from the Sea

Air Date: Week of November 20, 2020

“Emily’s Oysters” are sustainably farmed in Casco Bay, Maine. (Photo: Courtesy of Emily Selinger)

Some like ‘em and others don’t but oysters can be eaten in many ways beyond the half-shell, and farmed correctly they nourish shallow waters. From his coastal Maine kitchen celebrity chef Barton Seaver joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about how oyster farming supports local economies and ecosystems, and whips up an oyster-flavored Thanksgiving stuffing.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

In the 19th century oysters were a popular food item in the US, especially with the advent of commerical food canning, and by 1900 Americans were gobbling down some 160 million pounds of oysters a year. But over consumption, sanitation concerns about raw oysters and the huge expansion of the beef and pork business that the railroads made possible, led to the oyster’s decline. Farmed correctly, oysters can be sustainable and their reefs protect coastal areas, so in recent years the popularity of local foods has spawned new oyster farmers—farmers that were hit hard this year with a drop in demand during the Covid crisis. Not everybody loves them of course, but oysters can be eaten in many ways beyond the half-shell. Celebrity chef Barton Seaver joins us from his kitchen near the harbor of South Freeport , Maine to show how oysters can even lend flavor to Thanksgiving stuffing. Barton welcome back to Living on Earth!

SEAVER: It's so nice to be back with you, friend.

CURWOOD: So tell me, why have the oyster farmers and fishermen been hit so hard by COVID-19?

SEAVER: Oysters are, well, they're so important to the restaurant industry. And that's where so many of us go to get them. By some anecdotal accounts, in March, April, May, large oyster dealers around the country I've talked to lost 98% of their business, who were selling into restaurants; some of that has come back. Massachusetts has some hard data, around about 60 to 70% of their oysters landed, that business was lost. So restaurants were the conduit, they were the marketplace for oyster farmers and for wild to sell their product.

CURWOOD: Yeah, where I live in southern New Hampshire is near the Great Bay, which, among the rivers coming into it is one called the Oyster River. And I noticed that there were folks who actually had set up stands along the side of the road to sell oysters individually to people.

Emily’s floating oyster farm. (Photo: Courtesy of Steve De Neef)

SEAVER: Yeah! Well, that's been one of the great success stories. And that's sort of the inherent nature of oyster farming is that these are small businessmen and women who are running a farm, and they are entrepreneurs, and they were able to pivot quite quickly. And as, in COVID, we turned our attentions anew to local food systems, oysters are a prominent part of that for those of us on the coasts. There is no food that is of place as much as are oysters, clams, mussels. And so that, that connectivity is there, in the taste of place, and it was really heartening to see those small farmers finding those pathways and for consumers to desire them and support them.

CURWOOD: Now, we know from history that Native Americans brought shellfish to the pilgrims that came here to the New England area in the 1600s. To what extent do you think oysters and shellfish should regain a place at the Thanksgiving table?

SEAVER: Well, oysters were one of the foundational foods of this country and long before the white man set foot on this continent, oysters were serving and sustaining native populations for aeons. "Hey, are you hungry? Cool, wait for low tide." Right? There's a pretty good menu out there! And in the first years of this country, and really through the early 1900s, oysters played a significant part of our diet. In New York City around the turn of the 20th century, New Yorkers were eating about seven pounds of oysters per person per year. But through decimation of local oyster populations in the wild, throughout the United States and our coastlines, we lost access to oysters, as well as, railroads created access to beef and revolutions in agriculture made animal products cheaper, more accessible, more available. And sort of, we lost our way as a seafaring nation as we turned towards a, another ocean that rippled with "amber waves of grain" instead of, instead of the tempestuous waves of the Atlantic.

CURWOOD: Now Barton I know you're a huge fan of oysters, but not just for their taste. Tell me why you think they're so important ecologically.

SEAVER: Oysters, amongst other shellfish, are you know, what was known as a keystone species. They're fundamental to the health of the ecosystems in which they are prevalent. They provide water quality, they provide habitat for countless other species. They are the bedrock upon which ecosystems' health and resiliency relies. And in the absence of wild oysters, because we've decimated them through overfishing, through disease, etc., habitat loss, oyster farming has stepped into the role of providing those ecosystem services, those vital services. And it was really oyster farming, clams and mussels, scallop farming as well, that really turned my attention as a chef away from sort of the guilty narrative of sustainability being, "Hey, how can we reduce the negative impacts we're having?" to thinking about oysters as regenerative, as our opportunity to improve ecosystems through our diet. To the point where oysters, clams, mussels are the only foods that I recommend outright overconsumption of. Because every oyster you eat encourages an oyster farmer, a small businessman or woman, to plant many more, to augment and expand upon those ecosystem services provided by them. And in that way, I think it's our patriotic duty to eat as many farm-raised shellfish as we can.

Oyster reefs provide important habitat and food for coastal species. They also help clean seawater and protect the coast from storm surge. (Photo: Roman Crumpton, USFWS, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Yeah, in fact, you know, as the storms pick up with climate disruption, oyster reefs are a great way to slow down the storm surge, huh?

SEAVER: Absolutely. We've seen this with Katrina, we saw this with Superstorm Sandy, that these vulnerable civic centers are made more vulnerable by the lack of those natural oyster reefs that naturally stopped those storm surges. And there's some really fascinating work going on around rebuilding reefs through commerce, which -- hey, I mean, environmentalism and social good on the half shell with a splash of Texas Pete and a six pack of beer over there, chillin, woo!! --

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

SEAVER: -- I mean, hey, you know, that's the kind of story that we need. And that's the kind of civic participation that is not a hard sell.

CURWOOD: No, no, indeed; already my mouth is watering. Hey, there's a project going on that The Nature Conservancy is a big part of, they're going out and they're buying up oysters that are otherwise going unsold to the restaurants during this pandemic, to help farmers who need to have a source of cash, and they're using those oysters to restore more shellfish reefs. Why is it important to have oysters in local communities? What is it about oyster farming that is so sustainable for localities?

SEAVER: Well, we are an agrarian nation, we really get the patterned rows of corn leading the eye off in undulating hills towards autumn splendor setting sun; the, the white farmhouse, picket fence, red barn, color fading, I mean, hot damn! You know, this is America, the very thread by which our fabric is woven. But we look out upon the water and sort of gaze wistfully at the wine-dark sea and think as though a fishery or a fish farm happens somewhere other, somewhere else. And I think it's so important that when we think about aquaculture, when we think about fisheries, yeah, we stand on that dock. But we, we turn around and we look at the quality of public education and the modest homes standing proudly on the hillside leading to the sea, we look at the opportunity for a daughter to follow in five generations of bootsteps to take helm of that boat and live and thrive in her community. And that is what oyster farming represents. In that truly American story, we see ourselves reflected, and we see our own values delivered to us on the half shell. Right here in my village, there's a young woman named Emily -- "Emily's Oysters". She grew up here, and she went to school out in Puget Sound, and she was looking for something to do and, you know, a classic case of the brain drain of small rural communities. But oyster farming caught her heart, you know, it brought her back to her place. And now she's farming 50, 60, 70,000 oysters out in the waters that I can see from my house, pretty much. And she's selling at local farmers' markets. And like, that, to me is the the quintessential story of success and of human sustainability acting in concert with our ecosystems. I mean, hey, that we can put that narrative so concisely on our Thanksgiving table celebrating not only our past, but evangelizing and enabling the next generation of ocean stewards, all through one delicious bite at a time, makes you feel good!

Emily Selinger of Emily’s Oysters. (Photo: Courtesy of Steve De Neef )

CURWOOD: Indeed. You have some delicious recipes, Barton, on your website. There's -- oh, the oyster risotto, the broiled oysters Rockefeller. And I believe you're going to show us how to make an oyster stuffing, being that we're close to Thanksgiving, huh? Now, I must say I never knew the stuffing on my Thanksgiving table could feature shellfish.

SEAVER: Right?! You know, and it's one of those dishes that I really like about oysters, oysters can be, I wouldn't say polarizing, but intimidating. I mean, it is the only food, Steve, that we eat regularly that comes to us inside of a rock.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Yeah! How do you open the thing? You gave me a lesson on how to do this a few years back, but the next time I tried it, I have to say I wasn't terribly successful. I mean, yeah, this, this animal's inside of a rock!

SEAVER: Right? And then, take this culinary advice on how to open it: "Well, Steve, grasp the oyster in the left hand, take a pointy knife and shove it towards your hand with full force." It's like -

CURWOOD: Yeah, I know!

Emily tends to her oyster cages. (Photo: Courtesy of Steve De Neef )

SEAVER: It's just, it's kind of against all of our intuition and best learning, this food comes comes inside of a rock, and we have to point a knife towards our hand to get it; however. It becomes this meditative skill. And yes, it takes practice, it takes time, but it is also this very sort of Zen thing, and I've shucked probably over 100,000 oysters in my life; you know, I'm well over Malcolm Gladwell's, you know, threshold there for expertise. But there's something so beautiful about that connectivity, when we do open it -- and, you know, protect yourself either with a glove or with towels, etc. And when you pop that open, you are seeing there in front of you this, this still-living creature that offers us this very visceral, sensory opportunity to experience the unseemly circus of "Life Aquatic" that is the microscopic ocean from which it eats. I mean, it's just this, wow! Hey, yeah, it's, it's worth the effort, you know, ultimately. But the Thanksgiving stuffing is something that I love because it doesn't require us to sort of put forth this pristine oyster. I mean, hey, your oyster is gonna get cooked down with butter and celery, sage, onion, chunks of brioche or, you know, whole wheat bread all simmered down together in a chicken broth or water and seasoned with the liquor of the oyster, that salt-fragrant glory coming through. Shove that under your turkey, roast it off, the bottom of it gets a little bit crisp, the oysters add that, that really just floral aroma to the turkey. It's, I mean . . . do I have your attention yet?

CURWOOD: Ah, you mean am I hungry? Am I, am I bumming that this is one of these COVID type of interviews where we're in different places and talking to each other electronically, because I can't be in your kitchen and consume this? Yeah! Still, I can almost smell it as a matter of fact, even as you describe it. We're going to post on the Living on Earth website, that's LOE dot ORG, some video of Barton preparing his, his oyster stuffing. So now's the moment, Barton, where we, we'd love to see you do that.

SEAVER: All right, well, it's not complicated. You start off with butter because well, because butter. And stuffing is really one of the easiest things and what I, what I love so much about it is that scent of sage, which is so autumnal and just sort of celebratory in its, its nature and flavor and aroma to me. And so I always look forward to the foods and the the dishes that incorporate that, and none I think more viscerally to the American experience than stuffing. Very simple recipe of just sautéing your base aromatics. I've got a couple stocks of celery, an onion that I've diced up. Sautéing that in butter, and I'm just going to keep that on until it wilts, which will be a few minutes here. And then I've got some of Emily's oysters who, who stopped by this morning at the house on her way to the market up in Bath, where you can find her. But I've got the, the liquor and the oysters perfectly shucked in there. All that flavor, that salt-fragrant glory of the, of the liquor. Let's see what else I got -- some brioche breadcrumbs that I just cut into pieces, toasted them off in the toaster oven until they were --

[CRUNCHING SOUNDS]

SEAVER: -- nice and crunchy. So, and here you go. Here come the sounds of the season, you've got --

[SIZZLING SOUNDS]

SEAVER: -- the butter starting to waft up into the room. I mean, this is a, this is at least what I live for.

CURWOOD: So not too hot there, just sort of lightly sautéing it, huh?

SEAVER: Yeah, you don't want to add color to it, necessarily. You don't want to change the flavor of the onion, the celery just so much as wilt it, integrate it into the dish. So, as I was talking about, the sage, as it begins to simmer and that butter, ooh!!

CURWOOD: Mmm!

SEAVER: I guarantee my wife is gonna walk down in T minus three minutes here at least and wonder what's going on.

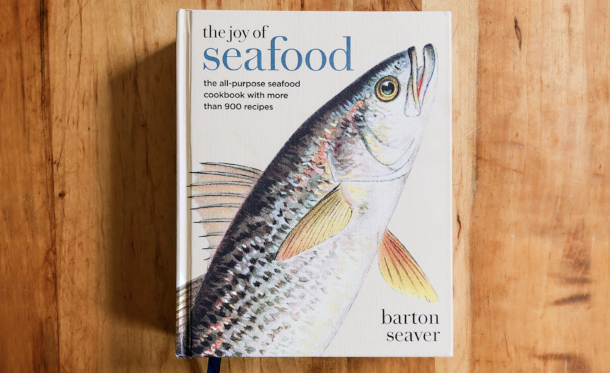

The Joy of Seafood: The All-Purpose Seafood Cookbook with More Than 900 Recipes is Barton Seaver’s latest book. (Photo: Courtesy of Barton Seaver)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

SEAVER: Also, one of the great joys is that this year, we've got a four year old son, who is just our best friend, and he's really starting to get engaged and interested in cooking. And this will be the first Thanksgiving that he can, um -- "help", quote-unquote. So I'm looking forward to that. And you know, the process of teaching children about food systems is so wonderful in that we get to walk down to the harbor and buy lobsters and mussels, clams, oysters from the men and women that are, are farming them or harvesting them is a, it's just a wonderful thing for him to see. And it builds in that innate thankfulness, gratitude for the products ultimately that sustain us. And you know, it's hard to explain to a four year old what sustainability is as a concept other than to say: Hey, kid, this will be here for you when you want to do this with your kid too. So, oyster liquor, a couple of oysters --

CURWOOD: Ooh.

SEAVER: -- one for me. . . .

Seafood chef and author Barton Seaver. (Photo: Courtesy of Greta Rybus)

[SIZZLING SOUNDS]

SEAVER: And there you go!

CURWOOD: Ah!

SEAVER: You're done! You know, you don't need to season it with anything more than the sage. We've already got the, you've got all of the, the saltiness, the brininess of those oysters to sort of fill that out. Just turn the heat off and as the continuation heat in the bread and the, in the celery begins to cook you see the, the mantle, those lips of the oysters begin to curl and -- I mean, hey, Steve, this is gorgeous. This is wonderful. And this is my lunch today. So thanks for the opportunity to make it for you. You know, the thing that I love most about cooking is that to feed someone is an act of love. It is an act of kindness. And that's why I love Thanksgiving so much as a holiday is, it begs us to consider our neighbors. And that plays into a sustainability narrative too, which is, while the idea of, the concept of sustainability might be very complicated, the action of it is very simple, and that is simply of being a good neighbor. When we look out for each other, we look out for the whole. And through food, we do that so intimately and with such love and deliciousness.

CURWOOD: Barton Seaver's latest book is "The Joy of Seafood: The All-Purpose Seafood Cookbook" with almost 1000 recipes. Thanks, Barton! Thanks for taking the time with us today.

SEAVER: Always a pleasure. I look forward to feeding you again in our kitchen sometime soon.

CURWOOD: To see Barton cooking up his oyster stuffing, go to the living on earth web page, LOE.ORG

Links

Watch Barton Seaver prepare his Oyster Stuffing

Barton Seaver’s website with recipes and his books

Learn more about Emily’s Oysters

The Guardian | "Sustainable Seafood: Why You Should Give a Shuck About Oysters"

About The Nature Conservancy project to buy oysters from farmers affected by Covid-19

Learn more internatinal oyster farms as well as oyster pairing and cooking.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth