November 20, 2020

Air Date: November 20, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

How Biden Can Keep It in the Ground

View the page for this story

President-elect Joe Biden has vowed to put the U.S. on a path to achieving "economy-wide net-zero emissions no later than 2050." Halting or reducing fossil fuel extraction on public lands will be among key steps the new administration will need to take in order to meaningfully move towards that goal. Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss how the Biden-Harris administration can pursue a new agenda on public lands and climate. (08:01)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s Beyond the Headlines, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss how coronavirus may be transmittable from humans to marine mammals through untreated wastewater. They go on to talk about how atrazine, one of the most widely used herbicides, may be harming endangered species and disrupting ecosystems, as well as affecting human health. And they wish a very happy birthday to Ted Turner, founder of CNN and longtime environmental champion. (04:16)

Down Yonder in the Pawpaw Patch

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

The pawpaw is the largest edible fruit native to the U.S., and it ripens in the late fall, outlasting many of the better-known local fruits like apples. Landscape designer and former host of PBS' The Victory Garden Michael Weishan gives Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb a taste of the fruit and some pawpaw trees for her to plant at home. (07:47)

Native American Traditions of Giving Thanks

View the page for this story

Thanksgiving is a time for many US families and friends to gather and be thankful, but for Native Americans it can also be a reminder of the displacement, violence and disease brought by the white colonists. Joe Bruchac, an author and storyteller of the Nulhegan Abenaki tribe, joined Host Steve Curwood to reflect on Thanksgiving’s complicated legacy for Native Americans and the long Native tradition of giving thanks. (09:54)

Sustainable Thanksgiving Fare from the Sea

View the page for this story

Some like ‘em and others don’t but oysters can be eaten in many ways beyond the half-shell, and farmed correctly they nourish shallow waters. From his coastal Maine kitchen celebrity chef Barton Seaver joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about how oyster farming supports local economies and ecosystems, and whips up an oyster-flavored Thanksgiving stuffing. (16:50)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

201120 Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Joe Bruchac, Pat Parenteau, Barton Seaver, Michael Weishan

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Our Thanksgiving tables may be a lot smaller this year, but they can still nourish our communities.

SEAVER: While the concept of sustainability might be very complicated, the action of it is very simple, and that is simply of being a good neighbor. When we look out for each other, we look out for the whole. And that's why I love Thanksgiving so much as a holiday, it begs us to consider our neighbors. And through food, we do that with such love and deliciousness.

CURWOOD: Also, some tips for growing a native fruit few people are familiar with, the paw paw.

WEISHAN: It's a delicious eating experience, prized by the Native Americans. Of course, this was a principal food source all up and down the East Coast. Great flower, great fruit, nice habit and great fall color. So if you can grow one of these in your yard, I highly recommend it.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

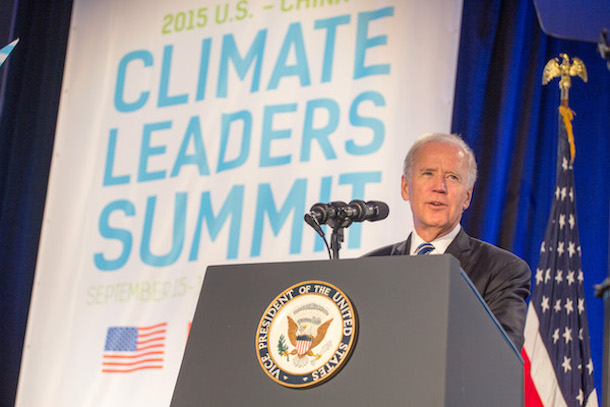

How Biden Can Keep It in the Ground

The Biden-Harris administration has pledged to move the United States towards a 100% clean energy economy, but this is challenged by national oil and gas extraction and a need for renewable energy sources. (Photo: The White House, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Just as President Trump’s denial of the science of Covid-19 is amplifying its deadly course, his denial of the science of climate change is speeding up the world’s rush into deadly climate disruption. All that will make for heavy lifting by the incoming Biden-Harris Administration as it will soon try to reverse and realign climate and environmental policies to respect the truth of science. Halting or reducing the exploitation of public lands to avoid adding more global warming gases to the atmosphere is a task the simple math of climate disruption demands. A key crucible to forge policy with scientific truth is the law, and joining us now to look at some legal tools for the Biden team to renew and boost federal climate protection efforts is Pat Parenteau of Vermont law school. Pat welcome back to Living on Earth!

PARENTEAU: Hey, Steve, good to be back.

CURWOOD: Now, on the scale of importance, how big a deal is it this protection of public lands when it comes to protecting the climate?

PARENTEAU: You know, everything is important, and no one thing is enough. So the protection of these public lands not only from the standpoint of eliminating oil and gas development, but just protecting the integrity of these landscapes, these ecosystems that are already under tremendous stress from climate change is important. So it's doing two things. It's reducing our use and reliance on fossil fuels, and bringing these alternative fuels and technologies online faster. And it's also preserving the resilience, as we call it, of the landscape to deal with things like catastrophic wildfires and drought and the release of pest organisms as a result of the warming of the temperature, and all kinds of conditions that are changing in response to these global changes in climate change. So there's lots of reasons why preserving our public lands, as stores of carbon, as ecosystems to support species of plants and animals that are under tremendous stress. These are the things that we have to start thinking about, and evaluating.

A picture of the Islands of Four Mountains in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. (Photo: Ed Bailey, USFW, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: One of the budget reconciliations that was passed during the Trump administration allowed essentially drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Sounds like Mr. Trump is maybe trying to move forward with that before he leaves office. What are the odds there?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, so that's another one where the federal government and the President has the authority to reverse that decision. If leases had been issued already, that would be a different situation, my understanding is they haven't actually awarded any leases. When that happens, it gets more complicated, because now people that have paid good money for the leases are going to argue you're taking a property right of ours, we purchased the right to develop these resources, you can't simply take it away. So it may be that we're really close to that situation, where the equities, as we call them, will shift in favor of the oil companies. But if he hasn't actually awarded leases, they can stop that program.

CURWOOD: And what now will happen with the pipelines, we have Keystone XL, we have Dakota Access, and a lot of litigation and concern about that, the Biden administration has promised to stop a Keystone XL, what's likely to happen now?

PARENTEAU: I think he might stop Keystone. Dakota Access is a more difficult one, because it's complete in the in the oil is flowing so that's a tougher one to completely stop. But Keystone XL, once again, he can do the reverse of what Trump did. Obama had blocked Keystone, Trump issued a permit to allow it, Biden can come in and do the same thing. This is a presidential permit to allow bringing this oil into the United States from Canada, the courts have said that's completely up to the President. So if President Biden says no, you can't bring oil from Canada's tar sands in Alberta into the United States, that's it, you can't do it. The Keystone pipeline also crosses a lot of federal land. And that's another authority, the President has to say, I'm not going to allow rights of way across federal land for this pipeline. I think the Keystone pipeline is one that Biden is very likely to do to spike to stop it, he's going to get some heat for that from the labor unions, because of course, building pipelines creates a lot of jobs, at least in the short run. So he'll have to take some political heat for that, and probably promised to replace those jobs with some other job growth programs he has in mind. But if he wants to really send a powerful signal, not just to the environmental community, but really to the world, that there's a new administration in power with a firm commitment to doing something about climate change that's the one thing that I think would do it.

The Keystone XL Pipeline was first proposed in 2008 and it was slated to carry as much as 830,000 barrels of heavy crude oil from the Alberta, Canada oil sands through South Dakota to Gulf Coast refineries. The picture above is of a protest against the pipeline in 2013. (Photo: Blink O'fanaye, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: The Trump administration rolled back on a scale of 100 environmental rules. And we don't have time to talk about all of those today, Pat. But what are some of the things that the Biden administration could do to reverse some of those rules right away and what are the things that might take a bit longer?

PARENTEAU: Right, so Biden has the authority to reverse all the executive orders that Trump issued with a stroke of a pen, he has the authority to direct his cabinet officers to reverse policies that have been adopted by the Trump administration, that can be done very quickly. The thing that's going to take longer is reversing the rules and of course, Trump rolled back a whole number of very critical rules including the Clean Power Plan, the fuel economy rules, the methane gas regulations and right on down the line as you said, over 100 of these rules and policies. For rules Biden is going to have to go through the same steps that Trump did to create the rules. So he's got to go back through the rule making process, he's got to provide public notice opportunity for public comment, he's got to build a record to explain why he's reversing what Trump had done in a way that Trump didn't do very well and Trump lost a lot of these cases in court, the Biden administration is going to have to be more careful and it's also going to have to keep its eye on this new supreme court with this very strong six to three conservative majority, because in the end, some of these really big rules, like greenhouse gas emissions from power plants, they're going to have to get five votes on the Supreme Court to be upheld. So that's a new dynamic. And Trump didn't face that but Biden will definitely have to take account of the fact that he may not have the support of the federal courts, which have been packed with Trump appointees. That's a new challenge for this administration. I think it's one they can handle but they're going to have to do so very carefully.

CURWOOD: How important is the clock here? Some might say that the Clean Power Plan rule making took too much time and was too close to the end to the Obama administration to avoid getting tangled up in the courts. In other words, if Mr. Biden wants to make these changes, how soon does he have to jump on them?

A rally in Washington, DC urging the Obama Administration to halt the extension of the Keystone XL tar sands oil pipeline. (Photo: Stephen Melkisethian, Flickr, CC BY-NC ND 2.0)

PARENTEAU: You know what, I think they're jumping on it right now. I know many of the people on the Biden transition team for EPA, including people like Joe Goffman, who was one of the authors of the Clean Power Plan and many more. So I think Biden's team day one will already be poised to start the work that's needed to reverse the Trump administration's legacy, if you will. So I think we're gonna see a fairly brisk approach from the Biden administration with really competent people carrying out these jobs. And I think they're going to have a much better track record in court going forward.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau, is a law professor at the Vermont law school. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Pat.

PARENTEAU: It's a pleasure to be with you, Steve.

Related links:

- Washington Post | “Trump rolled back more than 125 environmental safeguards. Here’s how”

- Politico | “‘Can Canada sell Biden on Keystone 2.0?”

- Washington Post | “Trump Officials Rush to Auction Off Rights to Arctic National Wildlife Refuge before Biden can Block It”

[MUSIC: Terri Hendrix, “Way Over Yonder in the Minor Key” on Talk to a Human, by Stephen William Bragg/Woody Guthrie, Wilory Records]

Beyond the Headlines

A new Canadian study finds that marine mammals like beluga whales may be particularly at risk of coronavirus from humans. (Photo: Jason Pier, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, let's take a look beyond the headlines now with our usual guide. That's Peter Dykstra. He's an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. He's on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter, how you doing? What's going on?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. We've heard a lot justifiably about the tragedies of COVID-19. A quarter of a million human beings killed in this country by the pandemic with warnings that the worst could be yet to come. Here's one more little thing that you probably haven't heard. COVID could be a risk if transferred from human beings to marine mammals.

CURWOOD: Hmm. So how would that happen?

DYKSTRA: It would happen through sewage untreated sewage, which is still the rule and in so many parts of the world. It could contain the virus, it can live up to 25 days and offers some pathways to be transferred in the water to animals like beluga whales, sea otters, other whale species, dolphin species, seals and more.

CURWOOD: And of course, the marine mammals are in so much trouble already. What else do you have this week?

DYKSTRA: There's a common herbicide, actually the second most common used in this country. Atrazine is used on all sorts of things from golf courses to Christmas tree farms, to dozens and dozens of different crops, notably corn, and local produce like tomatoes. And we are told by the EPA, which just renewed Atrazine to be used for another 15 years, that in spite of that fact, Atrazine could cause harm to as many as 1000 already threatened and endangered plant and animal species.

CURWOOD: Well, I'm scratching my head on this one, Peter, because Atrazine has been linked to everything from breast cancer, prostate cancer, birth defects, neurological problems in people and such. It's pretty bad for humans, and yet it's been approved for another 15 years.

DYKSTRA: Welcome to the Donald Trump era EPA where industrial interests come ahead of environmental protection, even in the Environmental Protection Agency.

CURWOOD: Of course, Atrazine is horrible for wildlife as well.

The herbicide Atrazine is mostly commonly used on corn crops. (Photo: Naoya Fujii, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DYKSTRA: There's some evidence that Atrazine has been responsible for chemically castrating some frog species. There are so many other species that could be at risk, not just from direct application of Atrazine to food, but spray drift from Atrazine sites to places nearby. And of course, water pollution. Atrazine is a major factor in pollution of the entire Mississippi river system. There are so many different ways that this ubiquitous chemical is potentially harming our lives and the environment around us.

CURWOOD: Okay, Peter, I'm ready for some better news. Maybe if we look back in history, we'll find something to cheer us up.

DYKSTRA: How about a birthday party that's near and dear to my heart. My old boss, Ted Turner, turns 82 years old. He was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, not in the south, on November 19th 1938. Ted, of course, founded CNN and is responsible for so many things in which he was way ahead of his time.

CURWOOD: And what? He's not only the father of CNN, but also Captain Planet, he would come to the society of environmental journalists meetings. I liked that.

DYKSTRA: He took all sorts of journalism very seriously. But he gave a big boost to covering the environment. Ted was a man way ahead of his time on climate change, on habitat, on endangered species, and on all manner of environmental issues.

CURWOOD: So let's have the Ted Turner party. Hmm?

DYKSTRA: Absolutely.

CURWOOD: Thanks! Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon!

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon. Happy birthday, Ted!

CURWOOD: And Happy Thanksgiving to everybody. And there's more in these stories on the living on earth website which is loe.org

Related links:

- More on how the coronavirus may be transmitted from humans to marine mammals

- More on how Atrazine disrupts ecosystems

[MUSIC: Bastian Fiebig Quartet, “Happy Birthday”]

CURWOOD: Coming up – The delicious paw paw fruit and some Native American traditions of giving thanks. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ray Charles, “Dawn Ray” on The Genius After Hours, by Ray Charles, Atlantic Masters]

Down Yonder in the Pawpaw Patch

The pawpaw tree is the largest edible fruit native to the United States. (Photo: Alice Crain, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

In many parts of North America, it’s well past harvest time, but not for the paw-paw. The paw paw is a native fruit in the Eastern US that ripens in the late fall. Paw paws were a delicious food source for Native Americans, as well for people escaping from slavery on the journey North to freedom. And there are still some paw paw patches feeding folks today, though you can’t find them in grocery stores. Last spring When Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb spoke with Michael Weishan, former host of the Victory Garden on PBS, about gardening amid the coronavirus, Michael offered to dig up a few of his paw paws for Bobby to try growing at home. She recently picked up some saplings from Michael and has our story.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

WEISHAN: Here are your paw paws, which we'll pull out in just a minute.

BASCOMB: Thank you so much.

WEISHAN: My pleasure. And you can see how the how much smaller the leaves are, compared to what we're going to be looking at. That reduction is typical of plants that don't like to be transplanted. So by next year, they should have leaves of regular size.

BASCOMB: And what's regular size?

WEISHAN: Well, come on down, I'll show you.

BASCOMB: Alright.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

WEISHAN: Welcome to my pawpaw grove. So in front of us is the tree, It's probably now about 30 feet tall and 15 feet wide. These are big, long lanceolate leaves, which simply mean shaped like a sword long sword shaped leaves about seven, eight inches long, three inches wide. And then as you go up, you see that they're starting to change color. And that they're a brilliant, brilliant yellow, which is one of the great fall features of this tree. And they're hanging right in front of us are the paw paws. So is that what you expected?

BASCOMB: I've seen pictures. So I wasn't a complete novice. I've never had one. I've never seen one in the flesh, so to speak. But um, no, I thought that they would be maybe bigger or greener or something.

WEISHAN: It looks something like a green potato, wouldn't you say?

Pawpaw trees provide a rich tropical fruit, whose flavor has been compared to that of mangoes and bananas. (Photo: Plant Image Library, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah, it's a green potato. They're sort of stuck together like a snow man or something .

WEISHAN: Yeah, exactly. They come they come sometimes combined, either they're big, long sort of cylinders, or they're, they're various sort of sets of circles. And sometimes they're just a single set of circle. So the fruit is very variable another reason why they're not in commercial production, because they're very variable. So it would be very hard to ship them. They're also, here you can feel one, they're also quite soft.

BASCOMB: Yeah, it's like a ripe avocado.

WEISHAN: Exactly. That's how you know they're ripe. You take them when they when you push them in, and they dent slightly with your thumb just like an avocado, then they're ready to go. If they fall off the tree, they have a tendency to get bruised. And again, that's why they're not really potentially shippable.

BASCOMB: They're pretty small, too. I mean, this one, I don't know, a quarter of a pound or something.

WEISHAN: Oh yeah, certainly less than a pound about four inches long, three inches long, something like that. See, but what's interesting about this is that these trees are very unusual in they form thickets. And these roots come from underground. So this for instance, this four or five, six foot tree here, right next to it is from an underground growth and they're all tied via underground runners. And so when you try to go dig one up, you sever the runner, which means the plant is really unhappy. So this again, makes for very poor commercial production, which is why you don't see these in local nurseries.

BASCOMB: Now do they only reproduce by sending out runners? Or can you also take a seed and grow it and get a pawpaw? Or is it gonna be more like an apple where you don't know what you're gonna get?

WESIHAN: Oh, you’re going to see the seeds in a minute, you can definitely plant the seeds. And presumably, that's how this was grown. And that would actually be an easier way to propagate than these cuttings because then of course, it would form the roots within the pot. And it would just be integral, you know, as opposed to being split up like this.

The flowers are really interesting too they’re beautiful long purple about inch and a half flowers of a dark sort of vermilion purple color. And, interestingly, they have very little smell or a very unpleasant smell depending on your nose. And they're propagated by flies, and not by bees, they bloom very early before the bees are active. And so there's a whole group of these plants that are propagated by flies and other alternative pollinators. And the paw paw is one of them.

Michael sent Bobby home with quite a few pawpaw fruits, in addition to some trees for her to transplant on her own property. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Now, my understanding of paw paws I was under under the impression that they grow really well in the south, like the Mid Atlantic region and New England was sort of pushing the envelope for paw paws. But yours looks pretty good here. Are they growing better in this region now? Or is this typically where they you would expect to find them?

WEISHAN: We are at the northern edge of the range. So how much further north they will go? I don't know. You're right. They're very well known down in the middle of Atlantic and southeastern United States. However, with the climate change issue, things are moving north. So they already have predicted that this zone where we are now six B will be closer to 7B within 30 years.

BASCOMB: Well, I'm in zone five.

WEISHAN: The nice thing about a paw paw at least these paw paws is that they're free, right? [laughing] So take them home plant it if it dies, try the seeds if it doesn't work, you know you're welcome back here anytime to eat the paw paws

BASCOMB: I'll turn up on your doorstep here I am. [LAUGHING]

WEISHAN: (laughing) No problem anytime.

BASCOMB: Thank you. Well, can we try them?

WEISHAN: Yeah, absolutely.

BASCOMB: Awesome.

[WALKING SOUNDS … TABLE SOUND]

WEISHAN: So, here we are outside in the rain, because of our COVID precautions trying paw paws this will be a first.

BASCOMB: Well it's a first for me on every score, I've never had one.

WEISHAN: I'm gonna just gonna cut this open and then split it apart. And it's you can see it's like a banana. So at this point, I'm gonna give you a spoon. And these are the big black seeds. And you just take the seeds out, and then scoop it out like you would custard.

BASCOMB: Hmm! It's so good. Not what I expected. Everybody says banana and mango. And it's got like, the texture of banana maybe, but…

WEISHAN: I think it's more like vanilla custard. Yeah, yeah.

BASCOMB: I gotta try another one. Huh, hmm, my kids are gonna love this.

WEISHAN: It's a delicious eating experience prized by the Native Americans. Of course, this was a principal food source all up and down the East Coast. A beautiful tree, great flower, great fruit, nice habit, and great fall color. So if you can grow one of these in your yard, I highly recommend it.

Bobby and Michael sampled one of the pawpaw fruits during their socially distanced walk. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: And the unusual thing too about them. I mean, they taste like a, like a tropical fruit almost here in New England, which is so unusual. But also I mean, we're into November now and you're just now harvesting these. That's pretty unusual. I mean, even apples are sort of on their way out at this point.

WEISHAN: Yeah, my apples are done. I think because they have originated from the South, they are used to a longer growing season. As you can see around as most of the trees have lost their leaves but the Pawpaw is still doing its thing.

BASCOMB: Great. Well, thank you so much. I'm really so grateful for your time and for the pawpaws and I can't wait to try them.

WEISHAN: Well, and I can't wait to have your family try them, you like them already.

BASCOMB: Well, I mean, I can't wait to try to grow them.

WEISHAN: Ah yes. Well, we'll see report back and I want 10% Okay. Thanks, Bobby. [laughing]

BASCOMB: Thank you. This is super fun.

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb speaking with landscape designer and former host of the Victory Garden, Michael Weishan.

Related links:

- Kentucky State University paw paw conference

- Click here to contact Michael Weishan and learn more about his landscape design work

- Hear our ‘Home Bound Gardening’ story with Michael Weishan from April 2020

- Hear our ‘Fall Gardening Tips’ story with Michael Weishan from October 2020

[MUSIC: Paw Paw Patch Instrumental vhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ILlRWANqalg]

Native American Traditions of Giving Thanks

Succotash is a traditional Native American dish consisting of sweet corn, lima beans and other shell beans. (Photo: Susan Lucas Hofman, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

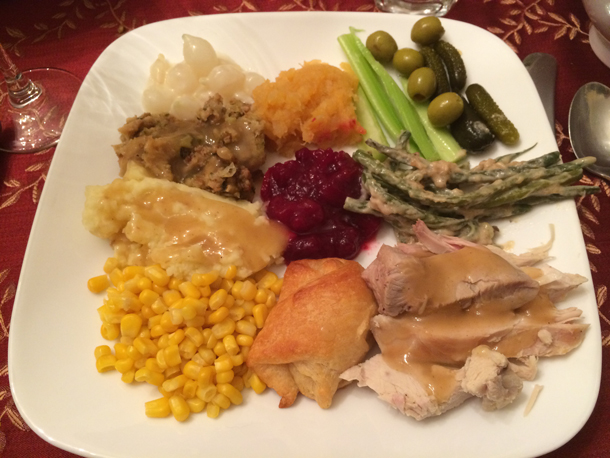

CURWOOD: Thanksgiving is one holiday that most Americans feel free to celebrate. No matter what religious or cultural background we come from many of us, in a normal year at least, will gather with friends and family on the fourth Thursday of November to feast on the foods of the harvest season. This year, of course is different, but the spirit of gratitude is still alive during the pandemic. But Thanksgiving is rather more complicated for the people at the center of the Thanksgiving story, Native Americans. There are nearly 600 Native American tribal nations in the US today, each with their own distinct traditions and culture. And to get some insight into some Thanksgiving traditions of the Nulhegan Abenaki tribe of Vermont and upstate New York, we reached out to storyteller and tribal elder Joe Bruchac. Joe, welcome back to Living on Earth!

BRUCHAC: Happy to be here.

CURWOOD: So, Joe, you can tell us what's your feeling generally about the Thanksgiving holiday?

BRUCHAC: I would describe it as ambivalent. It was always very important to when I was a kid growing up but when I looked at it from the viewpoint of Native people, especially here in the Northeast, there is a lot of cultural and historical baggage connected to it, that makes some native people describe it not as a day of Thanksgiving, but a day of mourning. Because of several things, of course, the dispossession of Native people that happened after that, supposed at first Thanksgiving, a number of Native Tribal Nations of the Northeast were either wiped out or driven from their homelands by the very European people who had originally been helped to by them to survive in this new land.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I mean, we're taught in school that Thanksgiving is this holiday framed around the early white settlers, the folks that came to Plymouth, Massachusetts inviting Native Americans to feast as a way of thanking them for their help and learning how to survive in the new world. So how is the holiday taught in your family and your community as you grew up? And how true does that narrative ring to you today?

BRUCHAC: Well, I think the complexity of it is varied. For example, the idea of thanksgiving as a national holiday was first proposed or I should say proclaimed by Abraham Lincoln after the Battle of Gettysburg to celebrate a great victory for the union. Further, in New England, they say the first Thanksgiving that was declared for the Massachusetts colony by John Winthrop, the governor, was after the destruction and the driving out of the Pequod nation. So you can see how there'd be some complexity there.

Native Americans ate and used cranberries as a natural dye. Cranberry sauce would not have existed during the first Thanksgiving event since sugar brought by the Mayflower would have already been depleted by November 1621. (Photo: Jim Choate, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Indeed. And of course, it's this time of year that school kids have been learning about Thanksgiving and they maybe made even pilgrim hats and feather headdresses. How do you feel about this way of teaching that part of American history?

BRUCHAC: Well, ironically, the Pilgrim hats they make are not the hats that the pilgrims wore. Okay. And the head dresses, they put on a little circles of paper with feathers sticking up, a lot of Native people feel that it's really not respectful of the way that we dress and it becomes a kind of parody because, as you know, so called ethnic minorities another term I don't particularly like, find themselves often parodied or stereotyped in majority culture. This is an example of, I think, a kind of stereotyping that I'd rather not see.

CURWOOD: So there are a lot of things about the holiday that seemed to have changed over the years, but the foods that generally get set out on the table have remained the same. Of course, there were wild turkeys back then corn was grown squash. To what degree are these types of foods still a part of some Native American cultures?

BRUCHAC: Sure thing, one the favorite dishes of Northeastern Native People is called succotash, which is a mixture of corn, beans and squash, who are called the three sisters of life because they provide and have always provided so much support for our people. And of course, corn and beans and squash are three of the gifts of Native People to the world. Whereas Europeans tended to deal in taming animals and making cows and pigs and horses, none of which were here part of their life in the North American and South American continents they were incredible agronomists, people who did plant breeding and created dozens, in fact, hundreds of varieties of corn and beans and squash.

Maple syrup harvesting is a longstanding Native American tradition. A maple tree needs to be forty years old in order to produce sugar maple sap. (Photo: Stanley Zimny, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: By the way back in those days in the Plymouth area at the coast, what we now call Cape Cod Bay I imagine there were plenty of lobsters. How did that feed into the menu the cuisine of Native Americans and the settlers at that time, do you think?

BRUCHAC: Without a doubt seafood was very important. Fish, crustaceans, such as the lobster, and other creatures from the sea were a very integral part of the diet. In fact, there's some question whether or not there actually was turkey at that first Thanksgiving but there, there certainly was seafood, there certainly, were those vegetables I've mentioned and I'm sure they also brought in deer because venison was a staple for the people at the time.

CURWOOD: Hey, um, tell me about your own family and friends. How do you celebrate Thanksgiving, if at all?

BRUCHAC: Actually, we do. We see it as an opportunity to bring people together to share food and I should point out that within our traditions, here in the northeast, one of the most important things we start with is giving thanks. It's not the idea of Thanksgiving, but the way it's been framed with an American culture that is difficult for Native people. And these Thanksgiving celebrations took place not just at the harvest time in November, but when the maple trees first gave their sap to make maple syrup, when various other plants and harvesting of various types was able to be part of the culture. So, that idea of harvesting and sharing and giving thanks is very deeply ingrained in our traditions. And it's certainly very much a part of my family. Every meal we eat we always begin with a Thanksgiving prayer.

The star of today’s traditional Thanksgiving dinner is usually a large roasted turkey, but it’s unknown if the same dish would have been served during the 1600s. Fish and crustaceans were bountiful at the time and would have formed part of the first Thanksgiving dinner. (Photo: Paulo O, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And what is that prayer?

BRUCHAC: We give thanks to the Creator, for the bounty that we've been given. We give thanks to our families, for their health and their good well-being. We give thanks to each other and to the land that sustains us. And, in fact, if you look among our friends slightly to the West, the Haudenosaunee, the Iroquois nations. They say that the Thanksgiving address a very formal enumeration of all the gifts of life from the earth, to the plants, the animals, the winds, the waters, the sun, the moon, the stars, the creator. All of these things must be thanked formally before any important occasion can begin.

CURWOOD: Talking to you, Joe, I realized I should be giving thanks for maple syrup and maple candy. For whatever reason, it escaped me that there's a strong Native American connection to this.

BRUCHAC: And I was told many years ago by Dewasentah, Alice Papineau, the Head Clan Mother, the Onondaga Eel clan, that when we get that first maple sap, it is a medicine given us by the Creator, that if we drink that sap straight from the tree, our bodies are going to be healed from the wounds and the troubles of winter, which I think is a beautiful way to look at it.

CURWOOD: And then traditionally, to what extent do you folks start to boil it down and make it into syrup and then of course the candy it can become?

BRUCHAC: Well, I could describe to some detail the traditional native way of doing it. You cut out Sort of a V in the tree, you put a little hollow piece of sumac there and collected in a bark basket which is watertight. And then you would pour it into a dugout canoe and by heating stones separately and dropping those red hot stones into the canoe full of sap, you'd boil it down and result in maple syrup which then if it was cooked further over a pot, you could turn into candy. In fact, one of the special treats of the wintertime would be to take very hot maple syrup and pour it on the snow which makes it immediately a little kind of candy that you can eat kind of like a snow cone

CURWOOD: And then you wind up with a bunch of sticky canoes?

BRUCHAC: Yeah, you would I guess set up with a sticky canoe although you don't fall out as easily joke, joke.

Joseph Bruchac is an author and storyteller from the Nulhegan Abenaki tribe. (Photo: Erik Jenks)

CURWOOD: Well, Joe Bruchac you are an author and a storyteller by trade. I wonder if you have a short story about Thanksgiving or gratitude that you care to share with us at this moment.

BRUCHAC: I think what I'd like to share in fact I know what I like to share something by Tom Porter, who is an elder of the Mohawk Nation, a truly wise person. Tom said that when the world was first created, our Creator told human beings, there was one thing you must do before all others. It is a simple thing: give thanks. Give thanks before you drink water, give thanks to your friends for the things they do for you, give thanks to all of creation and all that you meet. Well, what happened then is it people became forgetful, they stopped giving thanks. And as a result, everything began to go wrong around them. That is when the creator set another messenger and this messenger brought various ceremonies that could be done to remind us of the importance of giving thanks. That is a very simple story. But one I think that is still true to us today. If we forget to give thanks and be grateful indeed, everything begins to go wrong.

CURWOOD: Joe Bruchac is an author, storyteller and elder of the Nulhegan Abenaki Tribe of Vermont and upstate New York. Joe, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

BRUCHAC: Oh, ,Wliwini Nidôba (thank you my friend in Nulhega) Thank you so much.

Related link:

Joe Bruchac’s website -- learn more about Joe Bruchac’s stories and work

[MUSIC: Joseph Fire Crow, “Horse Stealing Song” on The National Parks: America’s Best Idea, by Joseph Fire Crow, PBS Distribution]

CURWOOD: Coming up a most unusual stuffing for your Thanksgiving table, made with oysters.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: R. Carlos Nakai, “Song for the Morning Star” on Canyon Trilogy, by R. Carlos Nakai, Canyon Records]

Sustainable Thanksgiving Fare from the Sea

“Emily’s Oysters” are sustainably farmed in Casco Bay, Maine. (Photo: Courtesy of Emily Selinger)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

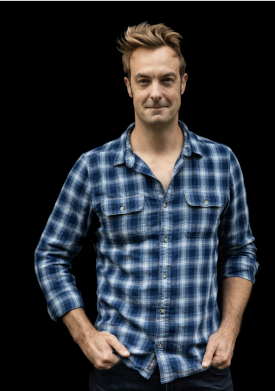

In the 19th century oysters were a popular food item in the US, especially with the advent of commerical food canning, and by 1900 Americans were gobbling down some 160 million pounds of oysters a year. But over consumption, sanitation concerns about raw oysters and the huge expansion of the beef and pork business that the railroads made possible, led to the oyster’s decline. Farmed correctly, oysters can be sustainable and their reefs protect coastal areas, so in recent years the popularity of local foods has spawned new oyster farmers—farmers that were hit hard this year with a drop in demand during the Covid crisis. Not everybody loves them of course, but oysters can be eaten in many ways beyond the half-shell. Celebrity chef Barton Seaver joins us from his kitchen near the harbor of South Freeport , Maine to show how oysters can even lend flavor to Thanksgiving stuffing. Barton welcome back to Living on Earth!

SEAVER: It's so nice to be back with you, friend.

CURWOOD: So tell me, why have the oyster farmers and fishermen been hit so hard by COVID-19?

SEAVER: Oysters are, well, they're so important to the restaurant industry. And that's where so many of us go to get them. By some anecdotal accounts, in March, April, May, large oyster dealers around the country I've talked to lost 98% of their business, who were selling into restaurants; some of that has come back. Massachusetts has some hard data, around about 60 to 70% of their oysters landed, that business was lost. So restaurants were the conduit, they were the marketplace for oyster farmers and for wild to sell their product.

CURWOOD: Yeah, where I live in southern New Hampshire is near the Great Bay, which, among the rivers coming into it is one called the Oyster River. And I noticed that there were folks who actually had set up stands along the side of the road to sell oysters individually to people.

Emily’s floating oyster farm. (Photo: Courtesy of Steve De Neef)

SEAVER: Yeah! Well, that's been one of the great success stories. And that's sort of the inherent nature of oyster farming is that these are small businessmen and women who are running a farm, and they are entrepreneurs, and they were able to pivot quite quickly. And as, in COVID, we turned our attentions anew to local food systems, oysters are a prominent part of that for those of us on the coasts. There is no food that is of place as much as are oysters, clams, mussels. And so that, that connectivity is there, in the taste of place, and it was really heartening to see those small farmers finding those pathways and for consumers to desire them and support them.

CURWOOD: Now, we know from history that Native Americans brought shellfish to the pilgrims that came here to the New England area in the 1600s. To what extent do you think oysters and shellfish should regain a place at the Thanksgiving table?

SEAVER: Well, oysters were one of the foundational foods of this country and long before the white man set foot on this continent, oysters were serving and sustaining native populations for aeons. "Hey, are you hungry? Cool, wait for low tide." Right? There's a pretty good menu out there! And in the first years of this country, and really through the early 1900s, oysters played a significant part of our diet. In New York City around the turn of the 20th century, New Yorkers were eating about seven pounds of oysters per person per year. But through decimation of local oyster populations in the wild, throughout the United States and our coastlines, we lost access to oysters, as well as, railroads created access to beef and revolutions in agriculture made animal products cheaper, more accessible, more available. And sort of, we lost our way as a seafaring nation as we turned towards a, another ocean that rippled with "amber waves of grain" instead of, instead of the tempestuous waves of the Atlantic.

CURWOOD: Now Barton I know you're a huge fan of oysters, but not just for their taste. Tell me why you think they're so important ecologically.

SEAVER: Oysters, amongst other shellfish, are you know, what was known as a keystone species. They're fundamental to the health of the ecosystems in which they are prevalent. They provide water quality, they provide habitat for countless other species. They are the bedrock upon which ecosystems' health and resiliency relies. And in the absence of wild oysters, because we've decimated them through overfishing, through disease, etc., habitat loss, oyster farming has stepped into the role of providing those ecosystem services, those vital services. And it was really oyster farming, clams and mussels, scallop farming as well, that really turned my attention as a chef away from sort of the guilty narrative of sustainability being, "Hey, how can we reduce the negative impacts we're having?" to thinking about oysters as regenerative, as our opportunity to improve ecosystems through our diet. To the point where oysters, clams, mussels are the only foods that I recommend outright overconsumption of. Because every oyster you eat encourages an oyster farmer, a small businessman or woman, to plant many more, to augment and expand upon those ecosystem services provided by them. And in that way, I think it's our patriotic duty to eat as many farm-raised shellfish as we can.

Oyster reefs provide important habitat and food for coastal species. They also help clean seawater and protect the coast from storm surge. (Photo: Roman Crumpton, USFWS, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Yeah, in fact, you know, as the storms pick up with climate disruption, oyster reefs are a great way to slow down the storm surge, huh?

SEAVER: Absolutely. We've seen this with Katrina, we saw this with Superstorm Sandy, that these vulnerable civic centers are made more vulnerable by the lack of those natural oyster reefs that naturally stopped those storm surges. And there's some really fascinating work going on around rebuilding reefs through commerce, which -- hey, I mean, environmentalism and social good on the half shell with a splash of Texas Pete and a six pack of beer over there, chillin, woo!! --

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

SEAVER: -- I mean, hey, you know, that's the kind of story that we need. And that's the kind of civic participation that is not a hard sell.

CURWOOD: No, no, indeed; already my mouth is watering. Hey, there's a project going on that The Nature Conservancy is a big part of, they're going out and they're buying up oysters that are otherwise going unsold to the restaurants during this pandemic, to help farmers who need to have a source of cash, and they're using those oysters to restore more shellfish reefs. Why is it important to have oysters in local communities? What is it about oyster farming that is so sustainable for localities?

SEAVER: Well, we are an agrarian nation, we really get the patterned rows of corn leading the eye off in undulating hills towards autumn splendor setting sun; the, the white farmhouse, picket fence, red barn, color fading, I mean, hot damn! You know, this is America, the very thread by which our fabric is woven. But we look out upon the water and sort of gaze wistfully at the wine-dark sea and think as though a fishery or a fish farm happens somewhere other, somewhere else. And I think it's so important that when we think about aquaculture, when we think about fisheries, yeah, we stand on that dock. But we, we turn around and we look at the quality of public education and the modest homes standing proudly on the hillside leading to the sea, we look at the opportunity for a daughter to follow in five generations of bootsteps to take helm of that boat and live and thrive in her community. And that is what oyster farming represents. In that truly American story, we see ourselves reflected, and we see our own values delivered to us on the half shell. Right here in my village, there's a young woman named Emily -- "Emily's Oysters". She grew up here, and she went to school out in Puget Sound, and she was looking for something to do and, you know, a classic case of the brain drain of small rural communities. But oyster farming caught her heart, you know, it brought her back to her place. And now she's farming 50, 60, 70,000 oysters out in the waters that I can see from my house, pretty much. And she's selling at local farmers' markets. And like, that, to me is the the quintessential story of success and of human sustainability acting in concert with our ecosystems. I mean, hey, that we can put that narrative so concisely on our Thanksgiving table celebrating not only our past, but evangelizing and enabling the next generation of ocean stewards, all through one delicious bite at a time, makes you feel good!

Emily Selinger of Emily’s Oysters. (Photo: Courtesy of Steve De Neef )

CURWOOD: Indeed. You have some delicious recipes, Barton, on your website. There's -- oh, the oyster risotto, the broiled oysters Rockefeller. And I believe you're going to show us how to make an oyster stuffing, being that we're close to Thanksgiving, huh? Now, I must say I never knew the stuffing on my Thanksgiving table could feature shellfish.

SEAVER: Right?! You know, and it's one of those dishes that I really like about oysters, oysters can be, I wouldn't say polarizing, but intimidating. I mean, it is the only food, Steve, that we eat regularly that comes to us inside of a rock.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Yeah! How do you open the thing? You gave me a lesson on how to do this a few years back, but the next time I tried it, I have to say I wasn't terribly successful. I mean, yeah, this, this animal's inside of a rock!

SEAVER: Right? And then, take this culinary advice on how to open it: "Well, Steve, grasp the oyster in the left hand, take a pointy knife and shove it towards your hand with full force." It's like -

CURWOOD: Yeah, I know!

Emily tends to her oyster cages. (Photo: Courtesy of Steve De Neef )

SEAVER: It's just, it's kind of against all of our intuition and best learning, this food comes comes inside of a rock, and we have to point a knife towards our hand to get it; however. It becomes this meditative skill. And yes, it takes practice, it takes time, but it is also this very sort of Zen thing, and I've shucked probably over 100,000 oysters in my life; you know, I'm well over Malcolm Gladwell's, you know, threshold there for expertise. But there's something so beautiful about that connectivity, when we do open it -- and, you know, protect yourself either with a glove or with towels, etc. And when you pop that open, you are seeing there in front of you this, this still-living creature that offers us this very visceral, sensory opportunity to experience the unseemly circus of "Life Aquatic" that is the microscopic ocean from which it eats. I mean, it's just this, wow! Hey, yeah, it's, it's worth the effort, you know, ultimately. But the Thanksgiving stuffing is something that I love because it doesn't require us to sort of put forth this pristine oyster. I mean, hey, your oyster is gonna get cooked down with butter and celery, sage, onion, chunks of brioche or, you know, whole wheat bread all simmered down together in a chicken broth or water and seasoned with the liquor of the oyster, that salt-fragrant glory coming through. Shove that under your turkey, roast it off, the bottom of it gets a little bit crisp, the oysters add that, that really just floral aroma to the turkey. It's, I mean . . . do I have your attention yet?

CURWOOD: Ah, you mean am I hungry? Am I, am I bumming that this is one of these COVID type of interviews where we're in different places and talking to each other electronically, because I can't be in your kitchen and consume this? Yeah! Still, I can almost smell it as a matter of fact, even as you describe it. We're going to post on the Living on Earth website, that's LOE dot ORG, some video of Barton preparing his, his oyster stuffing. So now's the moment, Barton, where we, we'd love to see you do that.

SEAVER: All right, well, it's not complicated. You start off with butter because well, because butter. And stuffing is really one of the easiest things and what I, what I love so much about it is that scent of sage, which is so autumnal and just sort of celebratory in its, its nature and flavor and aroma to me. And so I always look forward to the foods and the the dishes that incorporate that, and none I think more viscerally to the American experience than stuffing. Very simple recipe of just sautéing your base aromatics. I've got a couple stocks of celery, an onion that I've diced up. Sautéing that in butter, and I'm just going to keep that on until it wilts, which will be a few minutes here. And then I've got some of Emily's oysters who, who stopped by this morning at the house on her way to the market up in Bath, where you can find her. But I've got the, the liquor and the oysters perfectly shucked in there. All that flavor, that salt-fragrant glory of the, of the liquor. Let's see what else I got -- some brioche breadcrumbs that I just cut into pieces, toasted them off in the toaster oven until they were --

[CRUNCHING SOUNDS]

SEAVER: -- nice and crunchy. So, and here you go. Here come the sounds of the season, you've got --

[SIZZLING SOUNDS]

SEAVER: -- the butter starting to waft up into the room. I mean, this is a, this is at least what I live for.

CURWOOD: So not too hot there, just sort of lightly sautéing it, huh?

SEAVER: Yeah, you don't want to add color to it, necessarily. You don't want to change the flavor of the onion, the celery just so much as wilt it, integrate it into the dish. So, as I was talking about, the sage, as it begins to simmer and that butter, ooh!!

CURWOOD: Mmm!

SEAVER: I guarantee my wife is gonna walk down in T minus three minutes here at least and wonder what's going on.

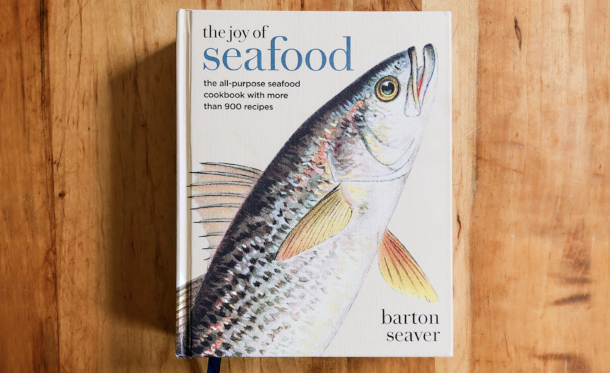

The Joy of Seafood: The All-Purpose Seafood Cookbook with More Than 900 Recipes is Barton Seaver’s latest book. (Photo: Courtesy of Barton Seaver)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

SEAVER: Also, one of the great joys is that this year, we've got a four year old son, who is just our best friend, and he's really starting to get engaged and interested in cooking. And this will be the first Thanksgiving that he can, um -- "help", quote-unquote. So I'm looking forward to that. And you know, the process of teaching children about food systems is so wonderful in that we get to walk down to the harbor and buy lobsters and mussels, clams, oysters from the men and women that are, are farming them or harvesting them is a, it's just a wonderful thing for him to see. And it builds in that innate thankfulness, gratitude for the products ultimately that sustain us. And you know, it's hard to explain to a four year old what sustainability is as a concept other than to say: Hey, kid, this will be here for you when you want to do this with your kid too. So, oyster liquor, a couple of oysters --

CURWOOD: Ooh.

SEAVER: -- one for me. . . .

Seafood chef and author Barton Seaver. (Photo: Courtesy of Greta Rybus)

[SIZZLING SOUNDS]

SEAVER: And there you go!

CURWOOD: Ah!

SEAVER: You're done! You know, you don't need to season it with anything more than the sage. We've already got the, you've got all of the, the saltiness, the brininess of those oysters to sort of fill that out. Just turn the heat off and as the continuation heat in the bread and the, in the celery begins to cook you see the, the mantle, those lips of the oysters begin to curl and -- I mean, hey, Steve, this is gorgeous. This is wonderful. And this is my lunch today. So thanks for the opportunity to make it for you. You know, the thing that I love most about cooking is that to feed someone is an act of love. It is an act of kindness. And that's why I love Thanksgiving so much as a holiday is, it begs us to consider our neighbors. And that plays into a sustainability narrative too, which is, while the idea of, the concept of sustainability might be very complicated, the action of it is very simple, and that is simply of being a good neighbor. When we look out for each other, we look out for the whole. And through food, we do that so intimately and with such love and deliciousness.

CURWOOD: Barton Seaver's latest book is "The Joy of Seafood: The All-Purpose Seafood Cookbook" with almost 1000 recipes. Thanks, Barton! Thanks for taking the time with us today.

SEAVER: Always a pleasure. I look forward to feeding you again in our kitchen sometime soon.

CURWOOD: To see Barton cooking up his oyster stuffing, go to the living on earth web page, LOE.ORG

Related links:

- Watch Barton Seaver prepare his Oyster Stuffing

- Barton Seaver’s website with recipes and his books

- Learn more about Emily’s Oysters

- The Guardian | "Sustainable Seafood: Why You Should Give a Shuck About Oysters"

- About The Nature Conservancy project to buy oysters from farmers affected by Covid-19

- Learn more internatinal oyster farms as well as oyster pairing and cooking.

[MUSIC: Toby Walker, “Hey Good Lookin’” on Hand Picked, by Hank Williams, Band In the Hand Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Leah Jablo, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aaron Mok, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Casey Troost, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. We pause to offer our condolences to intern Leah Jablo and her family and reflect on the life of Cyril Jablo, her grandfather and one of the quarter million Americans who have so far lost their lives to the Covid 19 pandemic. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth