Produce and Microplastics

Air Date: Week of December 11, 2020

Microbeads, such as those in many skincare products, have been showing up in the world’s waterways en masse. (Photo: MPCA Photos, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Degraded plastic is just about everywhere, including on farmland, and researchers are finding large amounts of microplastic particles in European and North American farm soil. They can range in size from five millimeters, about the width of a strand of spaghetti, to microscopic, the size of a virus. Freelance journalist Kate Petersen joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about how microplastics get into our soil and the risks they could pose for food.

Transcript

O'NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. Many people are concerned about pesticides in our food, and new research suggests there is another potential contaminant that we should be aware of. Plastic. Researchers are finding literally tons of microplastic particles on farmland. They can range in size from five millimeters, about the width of a strand of spaghetti, to microscopic, the size of a virus. A buildup of microplastic on farm soil raises concerns about degrading farmland and of course the safety of our food. Freelance journalist Kate Petersen has been digging into the story and joins me now for more. Kate, welcome to Living on Earth!

PETERSEN: Thank you. I'm happy to be here.

BASCOMB: So Kate, first of all, give us a quick background. How are microplastics getting onto farmland?

PETERSEN: Sure, there are a few different ways that microplastics get onto farmlands. One of those is through sewage sludge, which is actually put on farmlands as a fertilizer product. So in a wastewater treatment plant, the water gets cleaned by kind of separating all of the solid material out of it. And that material is coming from households, and, you know, industry and then also just runoff from streets into the sewer and things like that. So they separate out all the solid material. And that material is where most of the microplastics are retained, whether they got there through car tires degrading on a road, or atmospheric deposition that ends up in sewer systems, or through microbeads in personal care products, or washing polyester clothing is a lot of ways they get there. So then it's concentrated in the sludge, and then that sludge gets put on farmlands as a fertilizer.

BASCOMB: And I understand that in some cases, farmers actually are putting the plastic on the land themselves directly. Can you tell me about that?

PETERSEN: Sure. Yeah, that's true. There are two ways. One is, again, through primary microplastics, intentionally manufactured microplastics, which are used to coat seeds to protect them, and then also, there's technology where fertilizer and pesticides are encapsulated in little microplastic beads that are intended to degrade in the soil, and then release those products over time. And then the second way is that the secondary microplastics that break down of larger plastic objects, and one of the big things that they talk about is plastic mulching: the US, Canada, Europe, China, it's common. And it's a way to maintain soil moisture levels and shade the soil so that weeds can't grow. And then those plastics can degrade into microplastics. In some areas, they're just left out on the soil to just degrade and then more plastic mulch is put over them the next season. And then in other places, they are gathered up at the end of the year. But disposal is really a challenge. Recycling is expensive, you have to get all the dirt and detritus off of them, and people will end up burning them or burying them or you know, they might go to a landfill and then they just degrade into microplastics there. So those are some of the main ways.

Sewage sludge applied to an agricultural field, where it will later be covered with soil. (Photo: SuSanA Secratariat, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: So how does all of that plastic on farmland affect the plants that are growing there?

PETERSEN: Right. So you know, that's another area of significant concern. They just this year formally identified microplastic intrusion into actual plant tissue. Italian scientists found it in just produce from the store, lettuce and apples and carrots. And previously, they had thought that the particles would be too large to penetrate plant cells. But that turns out not to be true, they can get into there.

BASCOMB: And just to be clear, are researchers finding actual pieces of plastic in the plants themselves, or the chemical components that make up that plastic or both?

PETERSEN: Actual pieces of plastic is what they found this year, just actual pieces of plastic that they, they could see with a scanning electron microscope and other kinds of microscopy technology. There's also evidence of compounds associated with plastic being concentrated in tissue of organisms that are exposed to plastic. For instance, Mary Beth Kirkham did a study where she exposed wheat plants to microplastics, and cadmium, which is a toxic heavy metal, and then other plants to both microplastics and cadmium. And she found that those plants that were exposed to both microplastics and cadmium had higher cadmium levels concentrated in the tissue versus plants that were just exposed to the cadmium. And her research is not the only research that has found something along those lines where the microplastics seem to be a vector for other kinds of compounds entering living tissue.

BASCOMB: Well, speaking of living tissue, that, of course, begs the question, what are the potential health consequences for people that eat the food that has plastic in it?

PETERSEN: As of now that is unknown. There's been studies in animals that have ingested microplastics that suggest that microplastics, like in plants, can move through the body can get lodged in tissue. You know, it's all preliminary. This research is just coming out now, but it doesn't look good.

BASCOMB: And to what degree can a consumer avoid plastic in their food by eating an organic diet?

PETERSEN: I don't know if anyone knows at this point, because organic farms still use those plastic mulches. There is still atmospheric deposition of microplastics that they've discovered this year or last year as well, that could be raining down on any farm anywhere.

BASCOMB: And you write in your story here about some research done on earthworms, you know, every gardener's best friend, and how they're impacted by plastic in the soil. Can you tell me about that, please?

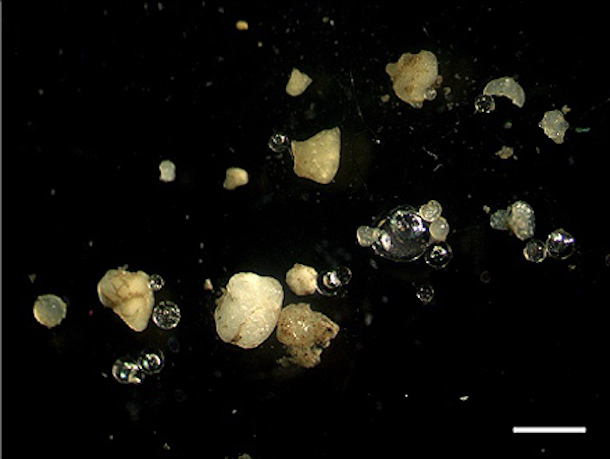

Microplastics, among sand and glass spheres in sediment from the Rhine river. The white bar shows one millimeter for scale. (Photo: Martin Wagner, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

PETERSEN: Yes, they did some experiments where they added microplastics to soil columns that had earthworms in them, and they found a couple things. One is that the earthworms did avoid the microplastics. But once the soil concentration reached about 7%, they began to ingest them along with the soil, and then would concentrate the microplastics like in their castings. And those castings are kind of the thing that people are really excited about with earthworms as far as being like, as fertilizing land and being this positive thing, but when there's microplastics in the soil, they start to get concentrated in those. And then they also found that the earthworms would move the microplastics through the different layers of soil, and so microplastics that were deposited up in the top soil would get transported farther down by the earthworms. And the concern there is not just it proliferating through the soil, but also the possibility that rainwater percolating through those earthworm burrows would enter the groundwater, and introduce microplastics into groundwater systems.

BASCOMB: Well, I mean, the problem is here. Now we know about it, what can be done at this point?

PETERSEN: Yeah, I mean, you know, it's a huge global problem. It has a lot of dimension obviously, and not just on agricultural lands, there's the products that are specifically for agriculture that are part of the problem, but there's all plastic products everywhere degrading and generating microplastics that then just move through the entire biosphere. So some suggestions of course, are, you know, repeating the call that's been issued a lot to limit or eliminate single use plastics, to only use plastics for things that are really important and are going to be around for a long time. Of course, there are campaigns to ban microbeads. The European Union is looking at banning those plastic seed coatings and slow release fertilizer microplastics. As far as the plastic mulch goes there, one call that I heard was for the companies that generate the plastic mulch to become responsible for it's recycling and disposal to take that burden off of farmers and make, you know, make that a financial burden of the company itself. And then also there is creating mulch out of cover crop which sequesters nutrients into the soil and gets mowed down and has some of those same properties of moisture retention, and weed control to try to truncate this pollution source.

BASCOMB: Kate Peterson is a freelance reporter. Kate, thanks for your time today.

PETERSEN: Thanks for having me.

Links

EHN | Microplastics in farm soils: A growing concern

Agribusiness Global | Microplastics in Agriculture: Challenges for Regulation

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth