December 11, 2020

Air Date: December 11, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Africa's Low Covid Fatality Rate

View the page for this story

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Africa has shown a surprisingly low fatality rate. Though the continent is home to 17% of the people on the planet, it only has reported 3.5% of the world's COVID deaths. Even with the knowledge that there may be underreporting, scientists are looking further to see if there may be other factors. Andrew Harding, Africa Reporter for the BBC, joins Host Aynsley O'Neill for more. (09:06)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week Host Aynsley O’Neill and Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra go beyond the headlines with a partly solved murder mystery: a killer behind mass coho salmon die-offs in the Pacific Northwest. Next, they highlight some heroes who came to the rescue of a coral reef damaged by one of this year’s many Atlantic hurricanes. In the history vaults, it’s 20 years since the last operating reactor at Chernobyl was finally decommissioned long after the infamous explosion of a neighboring reactor. (03:56)

Journeys North: The Pacific Crest Trail

View the page for this story

Every year, several hundred intrepid hikers walk all the way from Mexico to Canada, along the Pacific Crest Trail. At more than twenty-six hundred miles long, it covers some of the most challenging and spectacular terrain in North America. But it’s not just about the pretty scenery, writes Barney Scout Mann in his book Journeys North: The Pacific Crest Trail. He joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about braving blizzards, bears and blisters, and the tight-knit community he and his wife Sandy found on their PCT hike. (19:24)

Produce and Microplastics

View the page for this story

Degraded plastic is just about everywhere, including on farmland, and researchers are finding large amounts of microplastic particles in European and North American farm soil. They can range in size from five millimeters, about the width of a strand of spaghetti, to microscopic, the size of a virus. Freelance journalist Kate Petersen joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about how microplastics get into our soil and the risks they could pose for food. (08:28)

‘Tis the Season for Green Gifts

View the page for this story

The holidays look different this year and some of us may not be able to gather with friends and family. But we can still show our appreciation for our loved ones with the perfect gift. Whether it’s a book of essays on the climate crisis or a solar powered phone charger, the Living on Earth team has some eco-friendly gift suggestions for everyone. (06:37)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

201211 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Andrew Harding, Scout Mann, Kate Petersen

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

O'NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Much of Africa seems to have a surprisingly low death rate from Covid19.

HARDING: The virus seemed to have been slow to arrive in Africa, but even then, I was talking to some of the pretty senior, prominent scientists here, the sort of Dr. Fauci equivalents, who were saying 'look, these numbers still don't quite make sense to us.

BASCOMB: Also, the culture of long distance hiking - from trail names to trail magic.

MANN: Trail magic is any act to kindness toward a hiker. Whether you have a bit of your town lunch left over. You’ve gone out on a day hike and you run into a longer distance hiker and you see them eyeing that piece of pizza you’re just planning on taking home and throwing away and you give it to them. And you just made their day. That’s trail magic and you who have done that is a trail angel.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Africa's Low Covid Fatality Rate

President Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa receives a shipment of N95 face masks and other Personal Protective Equipment. (Photo: GCIS, GovernmentZA, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

O'NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

The COVID 19 infection and death rates across the African continent are turning out to be lower than previously feared, to the astonishment of scientists and public health workers alike. Africa is home to 17% of the world's population, but the continent only accounts for 3.5% of the world's reported COVID deaths. Even with the knowledge that there may be some underreporting, epidemiologists are still puzzled by what they are seeing. Andrew Harding is the BBC's Africa Correspondent. He joins us now from Johannesburg for more. Andrew, welcome to Living on Earth!

HARDING: Thank you very much for having me.

O'NEILL: So, Andrew, how do the death rates from COVID-19 in South Africa compare to other parts of the world?

HARDING: Well, South Africa is a bit different from the rest of the continent. The death toll here is creeping above 20,000. But the likely death toll from COVID may well be near a double that, that's what even officials here recognize, their figures aren't exact. That seems to compare, quite similarly to places like Britain, which has a similar population, if those figures stay the same and bear out. I think the greater confusion as in other parts of Africa, where the death toll seems to be significantly lower. But there are still tests being done here to to understand quite how many people here have been affected, and there are suspicions among scientists I'm speaking to, that actually a lot more people have been affected, but without symptoms.

O'NEILL: And how reliable are those numbers for South Africa and the rest of the continent?

HARDING: Well, the scientists have generally argued that the statistics, the data in South Africa, which is a very sophisticated economy, and health system in many ways, are pretty good. The concern has always been in poorer parts of the continent where a lot of countries with really very underfunded, under-resourced health care systems. And the concern there has been that really no one has a clue about how prevalent the virus has become. Because simply no one is doing the test, you pick up a war torn country like the Central African Republic, and they're just doing basically a few hundred tests, rather than the tens of thousands, or millions that need to be done.

COVID-19 testing in Madagascar on March 31, 2020. The country’s first confirmed cases were less than two weeks prior, with three cases confirmed on March 20. (Photo: Henitsoa Rafalia, World Bank, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O'NEILL: What originally caught your eye and caused you to start investigating this? You know, the case numbers, what caught your eye with that?

HARDING: Well, I've been trying to follow and to understand this right from the start. And a few months ago, I was talking to some of the pretty senior prominent scientists here, the sort of Dr. Fauci equivalents here in South Africa, Professor Salim Karim and others who are saying, look, these numbers still don't quite make sense to us. I think there are lots of reasons why Africa has done relatively well so far. But the scientists were saying, some of these figures still don't add up. And there was lots of speculation about why. And this was a continent, you have to remember, that is used to diseases, used to viruses, and used to really grim death tolls. And so people were very worried here, that Africa would really face a very devastating toll from COVID-19. And that doesn't seem to have happened. It has, to some extent in South Africa, and in some of the northern countries, but across vast amounts of this continent, they seem to be having a much easier time. And the scientists I was talking to here was scratching their heads, and wondering whether, as well as the key things we already know, for instance, demographics, the fact that the average population is 19, 20, 21, compared with the early 40s, in Europe, in America, so a much younger, much stronger, if you like, population. And far fewer elderly people in their 70s and 80s, who of course, tend to be the ones who die from COVID-19. So people obviously took that factor on board. And they took the fact that African governments, by and large, responded very quickly and very aggressively with lockdowns out of a sense of acute vulnerability, and also out of the sense that the virus seemed to be slow to arrive in Africa. So they had a bit of extra time, if you like, to get their act in gear, and they'd done a good job with that. But even then, the scientists I was talking to here, we're going, we still are not sure that that explains everything. Maybe there are other factors involved. And that's where it gets a lot more complicated, and frankly, a lot less clear, because the science is still in its early stages. But people are looking very hard right now with studies to see whether there might be some degree of prior immunity, perhaps because of exposure to other coronaviruses in the past, to other viruses. And perhaps as well because of exposure to more different types of jabs and inoculations. That people are saying, well, these kind of jabs may give your immune system a boost, or at least get it rehearsing more more effectively for what comes next. So all these theories are now being tested very aggressively, both in the United States and in Africa, and around the world as scientists still I think are trying to understand what on earth is going on here.

It’s likely that Africa’s low COVID death rates have to do with the relative youth of the continent’s population, but scientists are investigating further. (Photo: Ousmane Traore, World Bank, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O'NEILL: What are some other reasons that scientists have been suggesting as to why, as you were saying, Africa has been doing better than expected?

HARDING: Aynsley, there have been a lot of theories. Some good, some discounted. For instance, early on, I think the key thing was, as I mentioned, that tough aggressive lockdown, people thought that must surely play a role. The demographics, clearly, I think that's beyond doubt, has played a role. People have talked about the distances here, the fact that Africa is not connected by travel to the rest of the world, in quite the same way as Europe and elsewhere. People tend to come in on flights, they tend to be wealthier people who might be better informed. This is very clearly what happened in South Africa, in the early stages. The first wave of infections was actually a group of skiiers, coming back from Italy, to Johannesburg. Wealthy people, they went and isolated very quickly in their own big houses far away from the general population. And the government very efficiently tracked them down. And that early wave was pretty much crushed, and it didn't spread into the general population. People also talk about the possibility that altitude might have an impact, the possibility that humidity and hot weather might have an impact. I think those have been increasingly played down, discounted. Some people have also talked about the fact that to some degree, this is still a very outdoor culture, if you like, a lot of people still live in the rural areas. It's harder for the virus to to spread when it's outdoors. People have also talked about the fact, as I mentioned earlier, about things like the BCG and MMRs, jabs, inoculations, that people have had earlier in their lives. And wondering whether that, maybe even anti-malarial medication, maybe those things are messing, if you like, with people's immunity, possibly positively, possibly negatively.

Nigerian healthcare officials attend the Federal Capital Territory Emergency Operations Center Meeting for COVID-19. (Photo: Mr. Asafa, CDC Global, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: And Andrew, I feel like it's not a stretch to say that all of this is all a bit muddy, a bit unclear, a bit mysterious. What are you keeping your eye on in the future to see what will help clarify things?

HARDING: Yes, I hope you can tell how cautious I'm being because the scientists keep telling me when people start getting ideological or wanting to prove something, that's where you have to be careful, you have to wait for the scientific consensus to build up, because some of these early tests can often prove one thing. And then another test comes along and proves something else, and it really does take time to build up. But I think what we're looking for particularly right now are tests of really detailed population mapping. So trying to understand particularly how the first wave of this pandemic affected different communities, and trying to understand by testing those communities in a really, really sophisticated, detailed way working out why the virus affected some communities more, and perhaps spared others. And clearly there are examples of the suburbs more likely to have been less affected than the more heavily populated townships and informal settlements here, where people tend to live three, four, five, six, seven to a room. And it's much harder to avoid passing a virus on, it's much harder to social distance in those conditions. But I think we're waiting to see the evidence of those tests to see if there could be more lessons learned and more explanations for the patterns and the paths that this particular virus has taken.

O'NEILL: Andrew Harding is the BBC's Africa correspondent. Andrew, thank you so much for joining us.

HARDING: Thank you, Aynsley.

Related links:

- BBC | “Coronavirus in South Africa: Scientists Explore Surprise Theory for Low Death Rate”

- BBC | “Coronavirus: What’s Happening to the Numbers in Africa?”

[MUSIC: Amanda Black, “Power” on Power, Sony Entertainment South Africa]

Beyond the Headlines

Coho salmon struggle up a stream in the Pacific Northwest. (Photo: Oregon Department of Forestry, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: It's time now for us to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. He's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org, and DailyClimate.org. And he's on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter! What do you got for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Aynsley. We're gonna look at a murder mystery in the Pacific Northwest. Every time a heavy rain would hit around Puget Sound and the Seattle area, there would be a die-off of coho salmon in all the spawning streams along the Sound. And scientists have finally put a finger on, not solving the crime, but at least finding the murder weapon.

O'NEILL: Alright, so we're thinking, what, Professor Plum with the candlestick?

DYKSTRA: Pretty close, but the scientists, the team of government and academic scientists from Washington State, California, British Columbia, have found that there's a preservative chemical in car tires that has been killing the coho salmon. The tires, of course, gradually degrade, they get washed into storm sewers, the storm sewers empty into streams. And they seem to be the major cause of these coho salmon die-offs that have been plaguing British Columbia, Washington State and the whole Northwest for decades.

O'NEILL: Well, Peter, does this murder weapon have a name?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, write this down, folks: It's 6PPD-quinone, a chemical that preserves tires. There are a lot of other areas where crumb rubber and tire are suspect to be health risks to humans, most notably on playing fields.

O'NEILL: Oh, yeah, like soccer fields, baseball fields or even playgrounds.

DYKSTRA: That's right.

O'NEILL: What else do you have for us, Peter?

The reef at Puerto Morelos in 2017. (Photo: dchrisoh, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: The first story is about a murder weapon. The second one is about people preventing the death of a cherished part of nature. In Puerto Morelos, Mexico, it's near Cancun, Hurricane Delta came through this year. You remember the Atlantic hurricane season went crazy, we went farther into the Greek alphabet for naming hurricanes that we've ever gotten. Late in the season, Hurricane Delta hit Mexico and Central America. And there was a group that called themselves the Brigade that got together to help save coral that had been damaged by Delta.

O'NEILL: Tell me more about the Brigade, Peter, who are they?

DYKSTRA: They're a group of tour guides, diving instructors, Park Rangers, fishermen, researchers. And what they did is get in the water right after the hurricane, as soon as the churning of the water died down. And they literally glued broken Elkhorn coral onto the main branches of coral. If you do that soon after a disruption, you can save coral. And that's what these human heroes did for some wildlife that's under serious stress.

O'NEILL: Gluing back the corals, that's a pretty heroic arts and crafts project, Peter!

DYKSTRA: Yeah, saltwater first responders.

O'NEILL: All right then, Peter. I think it is time now to look through the history vaults. What do you have for us?

Ghost city Pripyat with the decommissioned Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the background. (Photo: spoilt.exile, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: We'll go back to the year 2000, December 15th, the last operating reactor at Chernobyl is decommissioned almost 15 years after that huge 1986 accident. Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union when the accident happened. After their independence, they wanted to keep any part of the complex operating that could help not only with jobs, but with electric power. And so it wasn't until 2000, almost 15 years later, that Chernobyl was finally officially shut down.

O'NEILL: Well, thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. And we'll talk to you again next time.

DYKSTRA: Okay Aynsley, thanks a lot, and we'll talk to you soon.

O'NEILL: And there's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- The LA Times | “Scientists Solve Mystery of Mass Coho Salmon Deaths. The Killer? A Chemical From Car Tires”

- The New York Times | “A Race Against Time to Rescue a Reef From Climate Change”

- The New York Times | “Workers Bid Ill-Fated Chernobyl a Bitter Farewell”

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Chris Potter, “I Had a Dream” on There is a Tide, Edition Records]

Journeys North: The Pacific Crest Trail

The Pacific Crest Trail runs 2,650 miles from the U.S. border with Mexico to the Canadian border. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

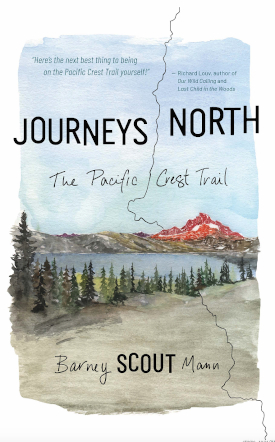

Every year, several hundred intrepid hikers walk all the way from Mexico to Canada, along the Pacific Crest Trail. At more than twenty-six hundred miles long, it covers some of the most challenging and spectacular terrain in North America. But it's not just about the pretty scenery. In his book Journeys North: The Pacific Crest Trail author Barney Scout Mann writes about the tight-knit community he and his wife Sandy found when they hiked the PCT. He joins us now from his home in San Diego, California. Welcome to Living on Earth, Scout!

The cover artwork of Journeys North by Obi Kaufmann depicts Thousand Island Lake and Banner Peak, notable sights on the PCT as it traverses the Sierra Nevada range. (Image: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

MANN: It's a pleasure to be here.

BASCOMB: So what drew you and your wife Sandy to hike the trail back in 2007?

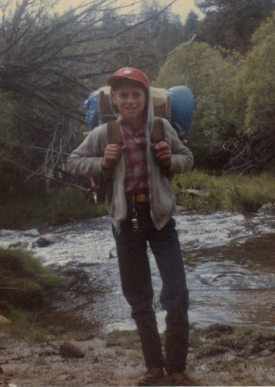

MANN: So you have to go a ways back. Both of us fell in love with backpacking at about the same age. I was 13 years old. And I was born into a household with parents who don't camp. But they took me at age 11, 12, 13 to Boy Scout meetings. And there at age 13, I went on a 50 mile backpack in the Sierra Nevada, John Muir's "Range of Light." I was, always been the smallest boy in any class at school, which is hard on a boy. It's no fun, I had to dance as fast as I could to make sure I wasn't the kid picked on, and it didn't always work. But out there, I saw stuff that I'd only seen on a TV screen, I grew up in Los Angeles. And so bears were not behind bars, I actually could see one. And hearing a beavertail slap in a stream, and seeing it. This was the real deal.

And the other thing was, out there, as long as I walked, and alright, I did have a 35-pound pack on a not-80-pound body, and that was hard, it was! But out there, as long as I kept up, I was the same as the big boys. So at age 13, I fell in love with backpacking. And for Sandy the same. My wife, Sandy, who has the trail name Frodo, and actually Scout is not my given name, but to thousands of people they only know us as Scout and her trail name, Frodo. She too, she'd see her brothers go off too on Boy Scout campouts, she'd think, I can hike! I want to do that. And it wasn't till later as a teen she got a chance.

Barney Scout Mann on his first 50-mile backpack in the Sierra Nevada in 1965, at the age of 13. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

And as she said, when we met a few years later, if I hadn't been a backpacker, she wouldn't have married me. In 2003, we'd already begun thinking seriously about doing a thru hike, as they call it, doing the entire Pacific Crest Trail. And we went out on the John Muir Trail, which is "only" -- and we use the word "only" very strangely in this community -- only 211 miles. We wanted to see if we'd come off that still being as enthused about doing a thru hike. And obviously we did, because in 2007, the summer of our 30th wedding anniversary, we set out to hike the Pacific Crest Trail.

BASCOMB: Mmm, wonderful. Well, let's get a lay of the land here. You start your trip from San Diego, you make your way down to the Mexico border, and then walk all the way up to Canada. How does the landscape change as the PCT makes its way from each border?

MANN: Well, there's both a micro and a macro answer. The macro is, it changes dramatically. You have some landscape that is out of Lawrence of Arabia, sand dunes, it's one day in the Mojave and you have some of it. And you have landscape that is, you are above treeline, it is barren, it is white granite that glitters in alpenglow. And you have everything in between. I saw one guidebook that identified 15 different plant and fauna zones, and the PCT goes through all of them.

Scout and Frodo at the Southern Terminus of the PCT, steps from the U.S.-Mexico border east of San Diego, California. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

But you might think, okay, I'll be walking and one day, I'll be in one thing, and then it'll slowly and gradually change. And it doesn't happen at all. The micro scale, literally in a half day's time, I can go through, easily, and many times, go through half of those different flora and fauna zones. I cross under a dirt underpass under Interstate 10, east from Los Angeles, at about 1800 feet, and I'm in what looks to you like desert. And within, okay, not a half day, but two-thirds of a day, I have climbed up into a pine forest and have gone through all the zones in between: the different desert zones; oaken. And the other thing, it's not just the landscape changing. Because we're out for five months, we're walking through seasons.

Every night on the trail, Scout would look up in the sky and spot the Big Dipper, follow it to the North Star, and just think for a moment: “That’s the way I’m heading. That’s what I’m doing.” (Photo: Patrick Beggan)

I see a plant, and actually, each of my three long hikes, I've done the Pacific Crest Trail, the Continental Divide Trail and the Appalachian Trail. Each one, there's a plant called skunk cabbage, or false hellebore. Each one of these trails, I would see it sprouting in the spring, just the little tiny tips coming up, almost like a bulb. It's only about a foot and a half tall, really thick, lush green, and it has little flowers. And I know I'm reaching the end of my hike, because at the first frost, a bit like a tomato plant, the plant just collapses. And it's like a starfish on the ground. And I know it's, my hike is beginning to end when I've seen that.

BASCOMB: Well let's talk a bit about the culture of these long hikes, starting with the idea of trail names. That's a nickname that's given to you by your fellow hikers. How did you get yours? And how did Sandy come to be known as Frodo?

MANN: So imagine if you got dropped down into a completely different place. If you woke up one morning and you were in Hogwarts, or you woke up and you were in Narnia, would you still want to be Bobby?

BASCOMB: Mmm, that sounds a little boring! [LAUGHS]

Frodo carefully crosses a stream in Oregon on a log bridge. (Photo: Barney Scout Mann)

MANN: This is actually a tradition that started on the Appalachian Trail. You do something stupid, maybe it's a play on your name. But trail names are usually given, sometimes thrust on you, rather than something you choose, although that happens on occasion. A guy who was named "Sky God" as his trail name, didn't take too long to realize that he had chosen that name for himself. [LAUGHS] The name Scout dates back to our 2003 John Muir Trail hike.

First day out, a young man attached himself to us like glue. Twelve miles later, we're climbing up Half Dome, and he was just out of high school, the two of us must have looked like parental types, and I hear this question behind me. And the question is, "What's the most important thing you've done in your life?" And at that point, I probably had three, four, five truthful answers to that. But the one that came out of my mouth was, "I was Scoutmaster of a large Boy Scout troop for five years." And "Scoutmaster" is a bit pretentious, and the book that we'd torn up -- and yes, we used to tear up books and put 150 pages at a time in our resupply up the trail so we wouldn't have to carry the whole book that time.

But the book we'd done that to, and that we were reading was To Kill a Mockingbird. And who would not want to be named after nine-year-old Scout Finch? Frodo -- I hope we have some LOTR, some Lord of the Rings fans out there. Frodo comes from, it's my fault. About a year before we hiked in 2007, I woke up and realized, oh my gosh, that's going to be the summer of our 30th wedding anniversary! She's not a jewelry person, but I really wanted to do something special. So literally, the idea sprang into my head, whole cloth. I could see a Pacific Crest Trail ring, a custom ring. And you could look at it from four or five feet away and you'd see the trail symbol, that "pregnant triangle", as we call it, with the tree in the center and the mountains backdrop.

The PCT ring that Scout gave to Sandy as they set out on the Pacific Crest Trail the year of their 30th wedding anniversary, earning her the trail name “Frodo”. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

And in the channel would be a small outline of the northern and southern monuments, and of the two primary mountains that you see on the trail, Mount Shasta and Mount Hood. I drove a jeweler crazy for about six months, but she actually did it! I give her the ring. We both cry. And if she was here, she'd say, Yeah, you cried more, which is true. I did! [LAUGHS] And the next day, we'd had a number of hikers who I had shown before I gave it to her, and all but as a group, they accosted her: "We want to see, show us the ring!" They said, "We know your trail name! You are the ring bearer. You're going on a long quest, a dangerous journey. You are Frodo!" And to this day, 13 years later, literally thousands of people, if not tens of thousands, know her simply as Frodo. And on her hand, she still wears the One Ring.

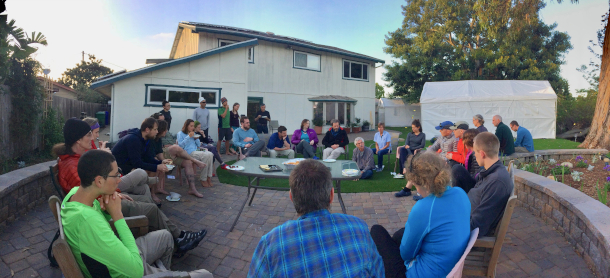

BASCOMB: Ah, lovely. And there are also people that are called trail angels. You and Frodo became known as trail angels for hosting people in your home. Can you tell us about that, please?

MANN: So you start with trail magic. And trail magic is literally any act of kindness toward a hiker, whether you pick up a hitchhiking hiker, whether you have a bit of your town lunch leftover, you've gone out on a day hike, and you run into a longer distance hiker, and you see them eyeing that piece of pizza you're just planning on taking home and throwing away, and you give it to them, and you've just made their day. That's trail magic. And you, who have done that, is a trail angel.

Scout and Frodo host an after-dinner talk with thru hikers, a few of the many thousands of hikers they have hosted over the years, about making the most of their PCT experience. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

And it goes from small to large. What we do is probably a bit large and maybe even obsessive. [LAUGHS] For about two months, we host hikers in our home. People from all over, about a third are internationals, and we'll have 30 to 40 hikers here a night, and we have this corps of volunteers, because it's all free. We had so much kindness in 2007 that came our way. You know, when we're out there in the small towns, we don't have the things we usually have at our disposal, and so many times and places along the way, we had trail magic, from trail angels. To be able to give back is, is great.

BASCOMB: That seems like something that's so rare in your day to day life, both A, relying on the kindness of strangers and having that appreciation for your fellow people and feeling like you want to give back to them, people that have been so generous with you.

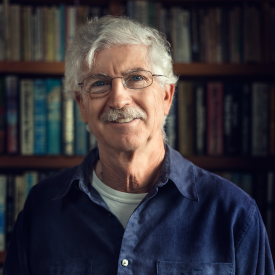

Barney Scout Mann is also a trail advocate who is currently serving as President of the Partnership for the National Trails System. (Photo: Patrick Beggan)

MANN: That's one of the things I love about the outdoors. It's one of the reasons I wrote the book too, so people who, their comfort zone is their couch, they can have a moment to experience what it's really like to be out there. And one of the neat things, as my wife likes to say, she thought the hike was gonna be so much about the landscape and stunning views, the pain and deprivation and trying, you know, the physical challenge. But at the end of the day, what it was really about -- gosh, I'm going to tear up a little bit! -- it was about the people. If you and I were coming at each other on a trail, and whether we're out there overnight, a week or, you know, in my case, five months, I would look at you from afar, a couple hundred yards away and say, "oh, there's another person!" I would think, "this person would give me the shirt off their back." And I would anticipate you would have the same thought in your mind, that the default attitude is we're kind to each other out there. I tell people that out there, on the trail, I found the community of people I've always wanted to be with, and I never knew existed.

BASCOMB: Is that what keeps you coming back to these long trail hikes that you do?

MANN: Why do I come back to it? A lot of reasons, a lot of reasons. One of which, of course, is that rich, rich sense of camaraderie. The other is -- well, the best way to explain it is, our hike of the Pacific Crest Trail is 13 years ago. And today, as I'm talking, I'm 69 years old. I was out there for 155 days. And Bobby, today, right now, I could sit here and tell you a story for each and every one of those 155 days. We are open out there in an entirely different way. We imprint differently. And around any bend, at any moment, a small miracle can happen.

BASCOMB: So you have this great story in your book about a big bear that you encountered on the trail one day. Can you tell us that story, please?

MANN: [LAUGHS] Yeah, I love it! Although it doesn't necessarily put me in the best light!

BASCOMB: Well . . . [LAUGHS]

MANN: So we are a thousand miles up the trail. We are actually just west of Lake Tahoe. And people we've leapfrogged with, that's, you'll see for a couple days, and you won't see for a week, or you might have a break with, and then see them the next day. They've all seen a bear! Not only that, they have their pictures, and they have their bear stories. And we have not seen a bear yet. What's wrong with us? And it's not that we haven't on many other earlier trips. But we don't have our Pacific Crest Trail bear story yet. And we've gone through the country where it's most likely, in the Sierra Nevada. So my wife and I are camping alone, which we did just over the majority of the time. And we were cowboy camping, which means not a tent, it was nice enough, and we enjoy that, to camp under the stars. We would trade off every night, one of us would do dinner and the other of us would set up our little campsite. So that's what I'm doing. I'm laying out our sleeping bags, my wife is about 20 feet away. And on the other side of her, about 50 feet away, I see pull around this large rock, the largest black bear I have seen in the wild.

Beautiful specimen, height of summer, sleek coat -- actually cinnamon colored, as black bears can be. And as I like to say, this thing was the size of a small Volkswagen. And I can tell, as I see him, I can tell by his aspect, where he's looking, he is not aware of us yet. The wind direction is such, and he's looking away. So what's my first move? Hmm. There's me, between me and the bear is my wife, right? My first move is a quick, hand down, camera up, and I get off two shots. [LAUGHS]

A black bear “the size of a small Volkswagen” approaches as Frodo cooks dinner. (Photo: Barney Scout Mann)

But all the way I'm watching him! And then I get her attention, I go, "fftt!", just make a little noise. She looks at me and I flick my head and she looks, sees the bear. And she takes the pot of food, puts it in our bear canister, cranks down the lid, comes over, stands by me. And she says "what do we do?" She knows: what you want to do is look large, and show them you're human. And I guess a lot of people think banging on pots means that we're human because that's what people can do, or clicking your hiking poles together. But what we did was we sang, in two-part harmony, Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah" to the bear. And as we reach the chorus, he turns his massive head and looks at us, long enough for us to know and acknowledge whose house we are truly in. And then he turns and slowly ambles away.

Scout and Frodo, a.k.a. Barney and Sandy, backpacking in 1977, the summer they were married. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

BASCOMB: So after walking some 2600 miles, you're just a few dozen miles from the border with Canada, from completing this entire hike that you've been doing, when a series of powerful snow storms dump just several feet of snow on the Cascade Range in Washington where you were hiking. What was it like to face that final test when you were so close from finishing?

MANN: Oh! We thought we had this in the bag. And at that point, this is now late September. At that point, you feel like you're in a vise. The days are growing shorter, so I have less time to walk. I see it all around me. I see it in the colors. I see the huckleberries are now gone and they're bright red. I feel it in the weather. And I feel it miserably at times in the weather. And you feel it in your body. I've been charging for now close to five months, and I'm getting messages from lots of different parts! And it's not just me, it's the young ones, too. We're being, we feel it. It's time to shut down. And we know, you can also feel, we have Canada in the bag! It's almost every year safe to finish by October 15th, I've seen people even finish October 31st. Because the snows at some point, shut down the trail. September 29, we are 60 miles from the Canadian border. We need three days and two nights. Unbeknownst to us, as you just said, a series of storms have lined up out of the Gulf of Alaska. And that night the first one hits.

I remember waking up and seeing the first snowfall: "Oh, this is sort of, you know, this is sort of cool!" And then as it starts to weigh down on the tent and you have to knock it off. And then it's, we're waking up to three, four inches already in the ground. And what's this going to be like? How much more is it going to go? And that day, we fairly quickly have a high pass. We're climbing first thing two thousand feet. We have a young woman, Blazer, one of the main other folks in the book Journeys North, we were close enough that she would call us her trail parents, her trail mom and trail dad, we'd call her our trail daughter. And Blazer, her, her jacket zipper's broken and she's lost a glove. I have, I have taught snowshoe backpacking. I'm experienced in snow backpacking. And as we get toward the crest of Cutthroat Pass -- what a name, huh! -- snow's been getting worse and worse, it's now over our ankles, and trail finding is an issue. This is days before anyone routinely carried a GPS or you had one on your phone. We have paper maps. And we see four people we know: Guts, Chuck Wagon, Dalton and Chigger. Do you love those trail names?

Frodo hikes in thick snow just 50 miles from the northern end of the PCT. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

BASCOMB: [LAUGHS] I do! Chuck Wagon, that's great.

MANN: Three guys and a gal, Chigger was a gal. They're heading toward us! Why are they heading toward us, this is wrong! And they say, "We have just turned around. The trail has become impossible to find. We're heading back to a road head. It's the last paved road, five miles back down at the base, and we're gonna hitch into the little tiny town Winthrop and see what the story is." We stand there in snow that's almost whiteout, and it's getting deeper by the moment. And for 10 minutes, I talk. Weighing it over; and, reluctantly I said, "Okay, maybe that is the best thing." And I turn and I take one step, South. I who have been heading north for five months. And I stop in my tracks. I can't go South. And I open my mouth. And I start to talk again. In the meantime, Blazer said I'm doing whatever Scout and Frodo are doing, and we felt likely the group would do the same. My wife and I had a tacit agreement. She did something that, as I'm talking there in the snow, it's the only time that she's ever done in our marriage. We've now been married 43 years. After about two minutes of me jawing again, she says "Scout, I'm exercising my veto. We're going back." I stop, stop talking. And we started heading down. And that was the first time [LAUGHS] we retreated from the snow!

BASCOMB: But you did finish eventually. You made it to Canada.

MANN: Yes, I'm still here. And we did make it to Canada that year, yeah.

BASCOMB: [LAUGHS] Yeah, I imagine; you make it sound like, you know, the geese that are flying South for the winter. They can't turn around and go North. That's just against what's ingrained in you at that point.

MANN: Yeah, yeah, there was this intense drive. Every night I'd go out and I'd brush my teeth. And on the Pacific Crest Trail, most nights were clear. And I'd look up in the sky and I'd spot the Big Dipper. And then I'd go from those two sides of the pot and I'd go six lengths out and I'd eyeball the North Star. And I'd just think for a moment. That's the way I'm heading. That's what I'm doing.

Despite three blockbuster snowstorms in the last miles of their hike, Scout and Frodo (pictured at far right), “trail daughter” Blazer, and the rest of their trail family did, eventually, make it to the border with Canada. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

BASCOMB: Scout Mann's new book is Journeys North: the Pacific Crest Trail. Scout, thank you so much for sharing all these stories with us.

MANN: It was a real pleasure, Bobby.

Related links:

- About Scout and Journeys North

- Learn more about the PCT

[MUSIC: The Wild Child, The Song Confessional “Going In”, Good Taste Society Music]

O'NEILL: Coming up – We’ll have some green gift ideas from the elves here at Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Donovan Martinez, “After Glow”, self published]

Produce and Microplastics

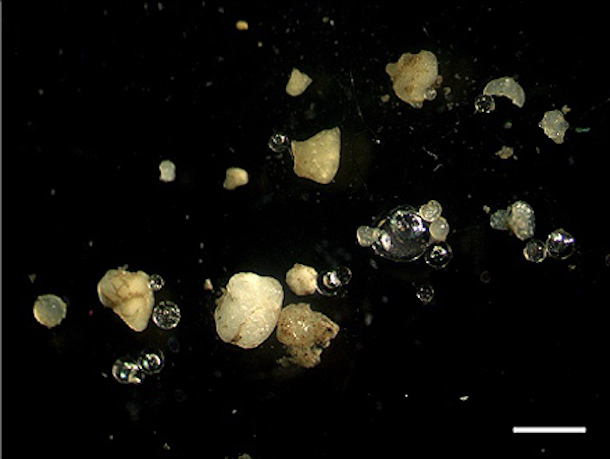

Microbeads, such as those in many skincare products, have been showing up in the world’s waterways en masse. (Photo: MPCA Photos, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

O'NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. Many people are concerned about pesticides in our food, and new research suggests there is another potential contaminant that we should be aware of. Plastic. Researchers are finding literally tons of microplastic particles on farmland. They can range in size from five millimeters, about the width of a strand of spaghetti, to microscopic, the size of a virus. A buildup of microplastic on farm soil raises concerns about degrading farmland and of course the safety of our food. Freelance journalist Kate Petersen has been digging into the story and joins me now for more. Kate, welcome to Living on Earth!

PETERSEN: Thank you. I'm happy to be here.

BASCOMB: So Kate, first of all, give us a quick background. How are microplastics getting onto farmland?

PETERSEN: Sure, there are a few different ways that microplastics get onto farmlands. One of those is through sewage sludge, which is actually put on farmlands as a fertilizer product. So in a wastewater treatment plant, the water gets cleaned by kind of separating all of the solid material out of it. And that material is coming from households, and, you know, industry and then also just runoff from streets into the sewer and things like that. So they separate out all the solid material. And that material is where most of the microplastics are retained, whether they got there through car tires degrading on a road, or atmospheric deposition that ends up in sewer systems, or through microbeads in personal care products, or washing polyester clothing is a lot of ways they get there. So then it's concentrated in the sludge, and then that sludge gets put on farmlands as a fertilizer.

BASCOMB: And I understand that in some cases, farmers actually are putting the plastic on the land themselves directly. Can you tell me about that?

PETERSEN: Sure. Yeah, that's true. There are two ways. One is, again, through primary microplastics, intentionally manufactured microplastics, which are used to coat seeds to protect them, and then also, there's technology where fertilizer and pesticides are encapsulated in little microplastic beads that are intended to degrade in the soil, and then release those products over time. And then the second way is that the secondary microplastics that break down of larger plastic objects, and one of the big things that they talk about is plastic mulching: the US, Canada, Europe, China, it's common. And it's a way to maintain soil moisture levels and shade the soil so that weeds can't grow. And then those plastics can degrade into microplastics. In some areas, they're just left out on the soil to just degrade and then more plastic mulch is put over them the next season. And then in other places, they are gathered up at the end of the year. But disposal is really a challenge. Recycling is expensive, you have to get all the dirt and detritus off of them, and people will end up burning them or burying them or you know, they might go to a landfill and then they just degrade into microplastics there. So those are some of the main ways.

Sewage sludge applied to an agricultural field, where it will later be covered with soil. (Photo: SuSanA Secratariat, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: So how does all of that plastic on farmland affect the plants that are growing there?

PETERSEN: Right. So you know, that's another area of significant concern. They just this year formally identified microplastic intrusion into actual plant tissue. Italian scientists found it in just produce from the store, lettuce and apples and carrots. And previously, they had thought that the particles would be too large to penetrate plant cells. But that turns out not to be true, they can get into there.

BASCOMB: And just to be clear, are researchers finding actual pieces of plastic in the plants themselves, or the chemical components that make up that plastic or both?

PETERSEN: Actual pieces of plastic is what they found this year, just actual pieces of plastic that they, they could see with a scanning electron microscope and other kinds of microscopy technology. There's also evidence of compounds associated with plastic being concentrated in tissue of organisms that are exposed to plastic. For instance, Mary Beth Kirkham did a study where she exposed wheat plants to microplastics, and cadmium, which is a toxic heavy metal, and then other plants to both microplastics and cadmium. And she found that those plants that were exposed to both microplastics and cadmium had higher cadmium levels concentrated in the tissue versus plants that were just exposed to the cadmium. And her research is not the only research that has found something along those lines where the microplastics seem to be a vector for other kinds of compounds entering living tissue.

BASCOMB: Well, speaking of living tissue, that, of course, begs the question, what are the potential health consequences for people that eat the food that has plastic in it?

PETERSEN: As of now that is unknown. There's been studies in animals that have ingested microplastics that suggest that microplastics, like in plants, can move through the body can get lodged in tissue. You know, it's all preliminary. This research is just coming out now, but it doesn't look good.

BASCOMB: And to what degree can a consumer avoid plastic in their food by eating an organic diet?

PETERSEN: I don't know if anyone knows at this point, because organic farms still use those plastic mulches. There is still atmospheric deposition of microplastics that they've discovered this year or last year as well, that could be raining down on any farm anywhere.

BASCOMB: And you write in your story here about some research done on earthworms, you know, every gardener's best friend, and how they're impacted by plastic in the soil. Can you tell me about that, please?

Microplastics, among sand and glass spheres in sediment from the Rhine river. The white bar shows one millimeter for scale. (Photo: Martin Wagner, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

PETERSEN: Yes, they did some experiments where they added microplastics to soil columns that had earthworms in them, and they found a couple things. One is that the earthworms did avoid the microplastics. But once the soil concentration reached about 7%, they began to ingest them along with the soil, and then would concentrate the microplastics like in their castings. And those castings are kind of the thing that people are really excited about with earthworms as far as being like, as fertilizing land and being this positive thing, but when there's microplastics in the soil, they start to get concentrated in those. And then they also found that the earthworms would move the microplastics through the different layers of soil, and so microplastics that were deposited up in the top soil would get transported farther down by the earthworms. And the concern there is not just it proliferating through the soil, but also the possibility that rainwater percolating through those earthworm burrows would enter the groundwater, and introduce microplastics into groundwater systems.

BASCOMB: Well, I mean, the problem is here. Now we know about it, what can be done at this point?

PETERSEN: Yeah, I mean, you know, it's a huge global problem. It has a lot of dimension obviously, and not just on agricultural lands, there's the products that are specifically for agriculture that are part of the problem, but there's all plastic products everywhere degrading and generating microplastics that then just move through the entire biosphere. So some suggestions of course, are, you know, repeating the call that's been issued a lot to limit or eliminate single use plastics, to only use plastics for things that are really important and are going to be around for a long time. Of course, there are campaigns to ban microbeads. The European Union is looking at banning those plastic seed coatings and slow release fertilizer microplastics. As far as the plastic mulch goes there, one call that I heard was for the companies that generate the plastic mulch to become responsible for it's recycling and disposal to take that burden off of farmers and make, you know, make that a financial burden of the company itself. And then also there is creating mulch out of cover crop which sequesters nutrients into the soil and gets mowed down and has some of those same properties of moisture retention, and weed control to try to truncate this pollution source.

BASCOMB: Kate Peterson is a freelance reporter. Kate, thanks for your time today.

PETERSEN: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- EHN | Microplastics in farm soils: A growing concern

- Agribusiness Global | Microplastics in Agriculture: Challenges for Regulation

[MUSIC: Benny Sings, Mac DeMarco, “Rolled Up”, Stones Throw Records]

‘Tis the Season for Green Gifts

December is the start of several gift-giving holidays, such as Hanukkah and Christmas. (Photo: PX Here, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: Hey Aynsley! So this year has gone by so fast. We're right in the middle of gift giving season already. Hanukkah just started this week and Christmas is just around the corner.

O'NEILL: I know! And what a weird year. A lot of people aren't going to be seeing many friends or family this season.

BASCOMB: Right. But you know, we can still celebrate just a little bit differently this year. So, to kick it off, we asked the crew here at the show to come up with some green gift ideas. But, no recycling that decades old fruitcake though.

O'NEILL: No, but one of our producers Paloma Beltran is thinking about food.

BELTRAN: Food has always brought my family together. For Christmas, we would all got together in my grandmother's kitchen to cook tamales. This year, we won't be able to gather in person. So, I'm giving my mom and my godmother a couples' virtual cooking class. That way, both of them can still pop a bottle of wine and celebrate the holidays. This is a bit selfish on my part because I'm hoping next year, they will cook for me.

CURWOOD: Hi, this is Steve Curwood, host and show producer, and I have to say one of my favorite gifts for people who like the outdoors from their backyards to the rich back of mountains is a nice pair of binoculars. You can get a decent pair for just $30. That includes a rubberized model good for kids. And you can get a really good pair for less than $100 from makers including Nikon, Bushnell, and Celestron. Just keep to seven or eight times magnification or 10 at the most. More magnification than that makes it harder to track birds and wildlife.

DOERING: Hi, I'm producer Jenni Doering. And a nice eco-friendly gift that's really inexpensive is wool dryer balls. You throw them in the dryer with their clothes, and they reduce the amount of time that your clothes and your laundry have to spend in the dryer. They also reduce static electricity, and you can put a bottle or two of a nice essential oil like lavender, lemongrass or tea tree in the gift. And just a dab of that on each ball will make the laundry smell just wonderful.

LENDER: I'm Mark Seth Lender, Living on Earth's Explorer-in-Residence. This year for every night of Hanukkah, I'm giving Smeagull the Seagull a can of sardines. Plentiful and low on the food chain, they are good for seagulls, good for humans, and using sardines and other small fish for food does not harm the oceans.

TROOST: Hi, I'm Casey and I'm an intern here. In the past few years, my family has started a tradition of putting nonprofits on the wish list. I personally like looking for small local organizations so I can give back to my community.

FEINSTEIN: My name is Jay Feinstein and I work on the production and business side of things. And I really recommend the new novel Migrations by Charlotte McConaughy. We actually just featured it on Living On Earth, which has been exciting. And it's this tale of this woman who wants nothing more than to follow the last migration of the Arctic turn set in the future. And it's just this really powerful tale that everyone will fall in love with. I love gifting books, and this is a good one.

The LOE staff wishes all our listeners a happy holiday season! (Credit: Ben White, Unsplash)

MOK: My name is Aaron Mok, and I'm an intern here. Now that the days are shorter, and we're stuck at home, an eco-friendly candle could be a great gift. Most conventional candles are made with petroleum wax and synthetic wicks, which are actually harmful to the environment when burned. But, you can find environmentally safe candles at a small business. Or if you're crafty, make your own. All you need is some beeswax, a cotton or wood wick, a container, and your favorite fragrances. And you're good to go!

ARENBERG: I'm Naomi Arenberg, and I choose the music every week for Living on Earth. My gift choice is the humble tea towel or kitchen towel. You can encourage the recipient to abandon paper towels, which we can't find in the grocery store anyway, and convert to cloth. And besides with so many of us spending more time in the kitchen than we ever thought possible, we should brighten up those kitchens with these beautiful miniature works of art in the form of the tea towel. Gift wrapping, not much necessary. Just take a cloth ribbon, cinch up that towel, and present it.

REGO: My name is Jake Rego, Technical Director at Living on Earth. This year, I will be gifting solar chargers to my friends and family. This will allow charging of cell phones and other electronic devices while off the grid. Happy Holidays!

JABLO: My name is Leah and I'm an intern at Living on Earth. One of the gifts I'm giving this year is the book Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality In A Divided World. We had the editor John Freeman on the show recently, and it's a collection of essays, short stories, poems and reportage by writers all over the globe about the relationship between the climate emergency and inequality. It's a great read, I think really beautiful and thought provoking and I think it would make a wonderful holiday gift for people who like a wide variety of stories.

KAUSCH: Hi, I'm Mark Kausch, and I help out with Living on Earth's stations that air the program around the country. At our house, we're giving our family some outdoor winter warmth. We picked out a smokeless fire pit for loving the opportunity to get outside even when it's cold here in Minnesota, and our neighbors are dropping by to catch up around the fire, which has been really fun. Everyone seems to love leaving the fire without smelling like smoke. And we're loving that we're keeping warm outside and avoiding putting a bunch of soot into the air.

BASCOMB: Those are some great ideas! What about you, Aynsley?

O'NEILL: My plan is to try making bird seed ornaments. You mix together bird seed and some gelatin. You roll it out, you cut it into cute little shapes with cookie cutters. And then you hang them outside for the birds to eat! How about you?

BASCOMB: Well, I've been thinking more about what's on the outside of the gift. You know a lot of wrapping paper isn't recycled or recyclable. So, I use brown paper grocery bags instead. I use some garden twine to tie it together with a sprig of evergreen and some red berries on top. They're lovely. Or I have my kids paint them which the grandparents love.

O'NEILL: That's so cute. Well, whatever is going inside those brown paper packages tied up with string, I'm really trying to shop locally and support small businesses this year. They're really struggling during the pandemic.

BASCOMB: Oh yeah, so important, especially this year. Well, we went through these ideas pretty quickly. But there's more information about all these guests on the Living on Earth website.

O'NEILL: Yeah, check it out at LOE.org. And I hope you have a great holiday, Bobby.

BASCOMB: You too. And everyone.

BOTH: Happy Holidays!

Related links:

- Better Homes & Gardens | 5 Smokeless Fire Pits That Let You Enjoy Bonfires Without the Irritating Smoke:

- Indie Bound | Migrations by Charlotte McConaghy:

- Indie Bound | Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality In A Divided World - Edited by John Freeman:

- Good Housekeeping | 8 Best Solar-Powered Phone Charges of 2020:

- Check Out Paloma's Choice of Cooking Classes | Palestine on a Plate

- Cozy Meal | Online Cooking Classes for Couples:

- Best Budget Binoculars from Business World:

- Digital Camera World | The best binoculars in 2020: binoculars for wildlife, nature and astronomy:

- DIY Natural | Learn to Make Homemade Felted Wool Dryer Balls:

- The Spruce | How to Make Birdseed Ornaments:

- EcoCult | 13 Places to Get Handmade and Eco-Friendly Candles and Incense:

- Well and Good | 7 Easy Ways to Upcycle Your Brown Paper Grocery Bags Into Wrapping Paper:

- The Grommet | Kitchen Linens & Tea Towels:

[MUSIC: E’s Jammy Jams, “Jingle Bells (Instrumental Jazz)”, Youtube Audio Library]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts.

O'NEILL: And like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth