A New Leader for USDA

Air Date: Week of February 19, 2021

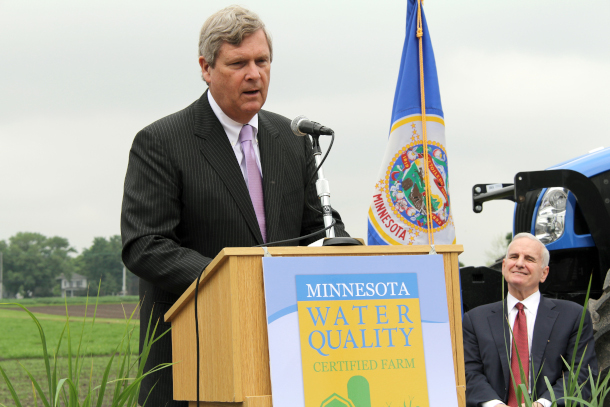

Tom Vilsack speaking about Minnesota Agricultural Water Quality Certification in 2013. (Photo: Julie MacSwain, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

President Biden’s pick for Secretary of Agriculture is Tom Vilsack, who would be reprising the role after his 8 years in the Obama administration. If confirmed as expected Mr. Vilsack will be tasked with aligning USDA with the Biden-Harris plan to address the climate emergency. Ricardo Salvador, the Food and Environment Director for the Union of Concerned Scientists, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss how “Vilsack II” is showing signs that since last serving as Secretary he’s become more supportive of food assistance programs and reforming historically racist programs at USDA.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

A final Senate vote to confirm Tom Vilsack as Secretary of Agriculture has been scheduled for February 23, and he has broad bipartisan support. The former Democratic governor of Iowa and one-time presidential candidate was also Agriculture Secretary for President Obama. But a lot has changed in the last four years. Catastrophic wildfires spurred by climate change have ravaged parts of the 200 million-acre National Forest system the USDA administers. And the Covid pandemic has tipped twenty percent of American households deeper into food insecurity and led to food shortages. Early on farmers, lacking a market were forced to dump milk and the virus ripped through meat-packing workers. During confirmation hearings before the Senate Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry Committee on February 2nd Tom Vilsack pledged to align the vast National Forest system with the Biden Administration goal of conserving at least 30% of US lands and waters by 2030. He also promised support of climate-smart agricultural practices to create new income and jobs for rural Americans.

VILSACK: I think there's an opportunity for us to create new markets incentives for soil health, for carbon sequestration for methane, capture and reuse of by building a rural economy based on bio manufacturing, protecting our force, turning waste material into new chemicals and materials and fabrics and fibers, creating more jobs in rural America creating greater farm income stability, and also reducing emissions.

CURWOOD: Tom Vilsack also said he would attack systemic racism at the USDA.

VILSACK: We need to fully deeply and completely address the long-standing inequities, unfairness and discrimination that has been the history of USDA programs for far too long, to a future where all are treated equitably, fairly, where there is zero tolerance for discrimination, where programs actually open up opportunity for all who need help and lift the burden of persistent poverty for those most in need.

CURWOOD: The biggest part of the Agriculture Department budget is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program which provides more than 40 million Americans with food aid. Secretary-designate Vilsack promised to reverse the actions of the previous administration, which tried to shrink food assistance benefits and failed to help many people who suddenly lost jobs and income in the pandemic. For some perspective on the Vilsack appointment, we are joined now Ricardo Salvador, the food and environment director for the Union of Concerned Scientists. Welcome to Living on Earth!

SALVADOR: Thank you, Steve. It's great to be with you. And I am glad that you've raised the confirmation hearing because there were some subtle nuances that many of us noticed during that confirmation hearing. Mr. Vilsack, to his credit, he of his own volition actually raised that it was important to think about the people that are not able to afford food, how he was actually going to prioritize making more of them eligible to participate in the Food Safety Network, which is the largest budget item in his department. And that's significant because his immediate predecessor had actually done the opposite. He was acting on a worldview that people that used the Food Safety Network were actually lazy, or were trying to cheat the system. So he was trying to make it as difficult as possible for people to qualify for SNAP what used to be called food stamps. So that's a significant difference in attitude and understanding of the purpose of the program that came from Mr. Vilsack. Likewise, he also didn't fall into line in that he actually said that it was very important to take into account the well-being and the health of laborers within the food system all the way from the fields into meatpacking plants. His immediate predecessor didn't even acknowledge those people exist. And if he ever did talk about laborers to him, those were inputs into the system that you know, whose costs were to be minimized. So what the traditional view in agriculture is, is that the laborers that are essential for the whole system operate just input costs, and you want to make your cost as low as possible. So when a secretary of agriculture speaks in the way that Vilsack did during his confirmation hearing, and he talked about them, needing occupational safety protection, that they needed to have a safe environment in which to work and that we needed to treat them with dignity. While in normal conversation that may just seem like it's expected for a secretary of agriculture to speak that way there is a sea change.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic food insecurity more than tripled in the United States. The image above shows the U.S. National Guard distributing food during the COVID-19 pandemic. (Photo: Cpt. Brendan Mackie, U.S. Army National Guard, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Particularly in meatpacking what say does the Secretary of Agriculture have over labor practices there?

SALVADOR: Yeah, that's a very good point because it would actually be OSHA, Occupational Safety and Health, or CDC, you know, so respectively, the Department of Labor and the Department of Health and Human Services that would have purview over a lot of the factors that determine how safe the environment is for workers in meatpacking plants. But the Secretary of Agriculture actually does have purview over one really important feature of the way that meatpacking plants work. And the Meatpacking industry, you have a disassembly line, you're essentially hacking away the pieces of the carcasses that are moving in front of you. And here's the key thing, the faster those carcasses are flying in front of you, and you hack away at the bit that you're responsible for, then the more profit the industry makes, you know, it's essentially how much can you process per unit of time. And if these were machines, you know, you could make an argument for that represent an efficiency because these are human beings, that's not efficiency that's exploitation. Because just so that you have an idea, depending on the species, we're talking about, say and poultry, you could be expected to hack away at about 181 of these carcasses per minute. And you're manipulating very sharp instruments and you can't stop because if you stop or if you miss it affects the entire disassembly line. So obviously the humane thing to do is to slow down the speed of those disassembly lines so that you actually have a humane occupation for these people to discharge. That is completely under the purview of the Secretary of Agriculture and prior secretaries of agriculture, not only Mr. Vilsack's immediate predecessor, but Mr. Vilsack himself when he was there, the first time actually supported the industry's demand that they sanction higher line speeds. So this is something that he can remedy because he can change things that he previously supported.

CURWOOD: So when Tom Vilsack was Secretary of Agriculture back during the Obama administration, the department was accused of discrimination favoring white farmers versus black and Hispanic and Native American farmers. And, in fact, among the cases that were filed, years ago, one of them called Keepseagle v. Vilsack resulted in millions in compensation for discriminatory claims. So to what extent do you think that Mr. Vilsack is going to change his approach to how farmers of color are handled by the USDA? Both in view of the lawsuits that had to be settled that had his name on it, and to any change in attitudes that you've noticed.

As the Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack would oversee the US Forest Service which has been dealing with catastrophic wildfire seasons due to climate disruption. (Photo: Mike McMiller, USFS, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

SALVADOR: Yeah. Well, if the only honest answer to that question is that that remains to be seen. Obviously, we would be just speculating right now. However, the way that Vilsack the second, you know, this is what I'm calling him now is shown up so far, is very different from the way that he presented the first time around. And one of the key indicaters of that is that when he held listening sessions with members of the African American farming community, he genuinely was listening, which we can tell because of the policies that he's recommending that the Congress move. But among these things, just to give you an idea, what I'm talking about is actually loan forgiveness for African American farmers. And actually a pause on foreclosures on African American farmers who are under great economic stress because many of them lost markets during the pandemic, every listener needs to understand that the history of the USDA has been racist from its inception in 1862. As a matter of fact, you can say with a straight face, its mission has been racist. You think of the year 1862 this is just before the Civil War starts out. The same President Lincoln who signed the department into existence also signed the Homestead Act, which basically distributed Native American land to white settlers. He also signed the Morrill Act, which essentially made a series of agricultural colleges exist in every state that largely served the overwhelmingly white farming population. To this day that population is 96% white, and they control 98% of agricultural land. That is the constituency that The Department of Agriculture has been serving and has been favoring. And the way that they express their racism is to those Farm Service Agency offices where both administrators as well as committees decide who is going to gain access to the federal funds, the programming, the low interest credit that goes out the front doors. And those lawsuits that you mentioned, essentially documented the extent of systematic discrimination against farmers of color and women. So to be fair to Mr. Vilsack, his name is attached to that lawsuit, because there was a lawsuit against the Department of Agriculture and he was the secretary. The one lesson that I think he learned from his first administration is that, while he may have theoretically been acquainted with the racist history of his department, he really left it up to subordinates and the department to try to remedy that as a result of the settlements of both lawsuits. And clearly, really did not deal with the underlying racism. And so now there's an opportunity to undo that. And so a key indicator that he means business is that he has stated publicly, he means to change the constitution of the Farm Service Agency offices, and who is actually made a member so that they're not primarily these white local groups that historically are just going to be benefiting themselves. So that's something we're going to be keeping an eye on in order to see the seriousness with which Vilsack the second is going to be approaching not only his charge, but also the promises that he's been making in public.

CURWOOD: I think it's fair to say that right now, the way the Agriculture Department operates with many farmers, involves the financial subsidy that they get through what's called crop insurance and such. And the bottom line is that if you're big and you have a nice balance sheet, your bank or the bank you deal with will accept that that federal guarantee is good to go and lend you the money. Whereas if you're small, and maybe not as rich, they may not even let you fill out the application or certainly, except that. To what extent then, are American taxpayers subsidizing the large agribusiness corporations that are squeezing out the small farmers?

SALVADOR: They're subsidizing it directly. That's entirely the purpose of farm programs and you've put your finger on something that many folks, even folks that are really familiar with agriculture don't fully understand. Let me give you an example of that many folks analyze those subsidies by saying that essentially what they're doing is helping to create an affordable food supply. So the food supply in the United States, first of all, is not affordable, it is one of the most expensive food systems that there is on the planet. But what people actually mean when they claim that the food system is affordable, is that if you're rich, you can buy what the US food system produces. So that's point number one, the subsidies to agriculture really not doing anything to make that food more affordable. Instead, you have to follow where those subsidies are going. Farmers do receive them and what farmers do with that is to buy their tractors by their seed by their fertilizer. And so if you follow the dollar, where it's ending up is the people that sell the fertilizer, the people that sell the seed. So the reason why this is significant in terms of farm subsidies, let's say that you're an industry that's producing expensive hybrid seed or you're an industry that's producing expensive equipment for farmers. You know, some of this equipment can cost 100 - $150,000 a shot. Then you're not going to be making the investments in those industries unless you're sure that those farmers are going to be there year in and year out to be buying those products from you. But because those farmers are vulnerable to a hailstorm or a cyclone essentially wiping out their business in 10 seconds, then that is not a safe bet to make that those farmers are going to be there. So now bringing in those those subsidies, we make farmers whole when the market goes south, we make farmers whole when a windstorm or hurricane, you know, hailstorm happens. So the ultimate beneficiaries, then it's the industries that sell to and that buy from farmers. So when you look at the lobbying that happens for agricultural programs, guess who's front and center and making the strongest arguments for that? It's those businesses is the businesses that sell to and that buy from farmers. That's what the agricultural subsidies are for. So the answer to your question is, we're directly subsidizing the major agribusinesses that otherwise are making arguments about how he loved the free market, but are the most socialized segment of the American economy. Those federal subsidies are actually built into their business models.

Ricardo Salvador is the Food and Environment Director at the Union of Concerned Scientists, and a former associate professor of agronomy at Iowa State University. While at ISU, Dr. Salvador taught what is regarded as the first course in sustainable agriculture at a land-grant university, and his graduate students conducted some of the original academic research on community-supported agriculture. (Photo: Courtesy of Ricardo Salvador)

CURWOOD: Let's talk a bit about carbon, the Biden Harris administration has said, we're going to deal with the question of climate change with an all of government approach. And there's much talk about the ability of farmland to help sequester carbon. For example, there's the in the USDA, there's a Commodity Credit Corporation. And there's some talk about having that become a carbon bank to pay farmers for practices that could limit greenhouse gases or even help extract them out of the air. How might this proved to be an effective incentive for farmers, when it comes towards moving the US towards dealing with a climate emergency? And how much do we know to accurately monetize such things at this point?

SALVADOR: So I'll give you the short answers. It's all to the good that we're moving to provide an economic incentive for farmers to contribute to mitigating climate change. And how much we know is not enough and as a matter of fact, is very limited in terms of monetizing those rewards. So there's a lot that we don't know, but which is knowable, and we just haven't invested in learning more about and that's the knowledge that the USDA has in its mission to generate. They just haven't chosen to do that to a large extent in the past. And now we have a real urgency to do that because the last thing that we want to do is to fritter away the moment when we have a president that recognizes climate change is real, human actions contribute to climate change, and we need programs in order to deal with this. And so when we go to say, okay, how do we incentivize and reward farmers to do that we don't want to do this in a way that commoditizes carbon so that then it becomes this sort of large volume, low value kind of proposition that is ultimately economically extractive and others other people benefit. And the farmers are the ones who benefit the least from that and to build a false economy where we think we're sequestering carbon, but we have no way of measuring it or and verifying how much actual carbon is being sequestered by agricultural practices. So yes, by all means, we need to get going on this and urgently it is it is really one of the most important Agricultural Science priorities that there is right now. But not delude ourselves about what we know so far, and what we need to invest in in order to learn more about

CURWOOD: Ricardo Salvador is the Food and Environment Program Director of the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SALVADOR: It was a pleasure. Thank you for having me, Steve.

Links

AgWeb | “Senate to Vote on Tom Vilsack’s Secretary of Agriculture Confirmation Next Week”

NY Times | “Goodbye, U.S.D.A., Hello, Department of Food and Well-Being”

Politico | “Black Farmers, Civil Rights Advocates Seething Over Vilsack Pick”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth