February 19, 2021

Air Date: February 19, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

India Climate Activist Jailed

View the page for this story

Amid ongoing massive farmer protests, the Indian government is cracking down on activists including Disha Ravi, the young climate activist who founded Fridays for Future - India. Freelance journalist Aditya Sharma joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss how climate activism connects with the Indian farmer protests, and the government’s attempts to silence activists and journalists. (08:30)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

For this week’s Beyond the Headlines segment, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discuss the theft of catalytic converters from cars across the nation, driven by the high prices of the precious metals they contain. They then cover the record levels of electric vehicle usage in Norway and reflect on the anniversary of the release of Al Gore’s award-winning film “An Inconvenient Truth”. (05:11)

A New Leader for USDA

View the page for this story

President Biden’s pick for Secretary of Agriculture is Tom Vilsack, who would be reprising the role after his 8 years in the Obama administration. If confirmed as expected Mr. Vilsack will be tasked with aligning USDA with the Biden-Harris plan to address the climate emergency. Ricardo Salvador, the Food and Environment Director for the Union of Concerned Scientists, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss how “Vilsack II” is showing signs that since last serving as Secretary he’s become more supportive of food assistance programs and reforming historically racist programs at USDA. (16:04)

The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World

View the page for this story

Insects far outnumber us on this planet, and they’ve shaped the course of human history. Edward D. Melillo, the author of The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to share stories about the ancient relationship between human society and insects, and the critical need to preserve insect biodiversity for future generations. (16:37)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Edward Melillo, Ricardo Salvador, Aditya Sharma, Tom Vilsack

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

Climate activists in India have been accused of sedition and jailed for supporting farmer protests

SHARMA: These activists shared a toolkit, a Google Document, which was posted on Twitter by climate activist Greta Thunberg. They've been charged with sedition and criminal conspiracy, when essentially what the toolkit does is creates and spreads awareness about the ongoing farmers' protests.

CURWOOD: Also, we share the earth with roughly 10 quintillion insects or maybe they share it with us.

MELILLO: Really in a lot of ways this is an insect planet that we’re just happening to live upon at this moment. Insects are governing all the basic processes that make life possible from plant sex to decay and all sorts of other crucial ecosystem services.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

India Climate Activist Jailed

Disha Ravi is the recently jailed 22-year-old climate activist who founded the Indian branch of the Fridays for Future network. (Photo: Disha Ravi’s Facebook)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The government of India is cracking down on climate activists who have joined farmer- led protests that have been escalating since November. Millions of farmers and their allies have shut down major roads across the country and set up make-shift camps in New Delhi, complete with generators, laundry service, and libraries, paralyzing the capital city. The farmers are protesting new laws that they say will benefit large agribusiness at the expense of small family farmers. At the same time climate-related disruptions have changed monsoon and drought patterns in India so dramatically that many people have been pushed out of farming all together.

BASCOMB: Authorities have jailed 22 year old Disha Ravi, who followed the example of Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg. Arrest warrants are also out for two of Ms. Ravi’s associates. Disha started an Indian chapter of the Fridays for our Future network in which millions schoolchildren around the world are striking for action on climate change. She has been organizing similar protests in India for some three years, and worked on a call to action called a ‘toolkit’ to help the farmer protests. It was retweeted by Greta Thunberg. That was cited as evidence of sedition by the government and led to Ms. Ravi’s arrest. Though it was not her first brush with the Modi government, which is highly sensitive to criticism. In July police took down a Fridays for our Future website that protested the planned dilution of environmental laws. For more I’m joined now by Aditya Sharma, a freelance reporter based in India who recently wrote about Ms. Ravi’s arrest for the German Media service, Deutsche Welle. Welcome to Living on Earth!

Indian farmers and allies protest the controversial new farm laws. (Photo: Randeep Maddoke, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 1.0)

SHARMA: Thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: So two of these activists have had a warrant issued for their arrest and a third was actually arrested. What exactly did they do?

SHARMA: These activists, they're actually environmental activists, climate campaigners. And they shared a toolkit, a Google document which was posted on Twitter by climate activist Greta Thunberg. They've been charged with sedition and criminal conspiracy. The authorities say that these activists were, you know, working with international conspirators to sort of discredit India, and that the toolkit is waging social and cultural war against the government of India, when essentially what the toolkit does is it creates and spread awareness about the ongoing farmers' protests.

BASCOMB: So what exactly was in the toolkit?

SHARMA: So, the toolkit calls for a tweetstorm, a social media buzz. That included, you know, hashtags such as #AskIndiaWhy. It mentions social media handles, it has articles, it also calls for protests at Indian embassies. So in a way, the toolkit's also targeted people living outside of India, who, you know, want to know more about the protests, essentially building a social media campaign and, you know, mobilizing support for the farmers.

Watch | 21-year-old climate activist Disha Ravi sent to 5 day police custody in Greta Thunberg "toolkit" case pic.twitter.com/48uaowdG51

— NDTV (@ndtv) February 14, 2021

BASCOMB: Now, I've read that the government has accused these activists of sedition and creating misinformation about the government. And they've even said that the three activists were in touch with supporters for an independent Sikh homeland in Punjab, what do you make of those accusations?

SHARMA: So sedition, to be honest, is like a colonial era law, which free speech activists and critics of this law say that this law has really no place in modern India. As far as criminal conspiracy is concerned, a lot of legal experts would, you know, argue that the charges don't really hold water. They're just, you know, like an overreaction to, you know, something that's part of campaigning and, you know, activism. This is just that the government feels threatened. As for the second part, the police says that these activists were in touch with a group that has links to the Khalistan movement, and the Khalistan movement, they want a separate, independent homeland in northern India. The Khalistan argument has sort of been the go-to argument for the government to discredit the farmers, because you see, the farmers protest is so strong. And all of this is an attempt to sort of discredit the movement, so that, you know, they can come and say that, "you know what, these people, they don't really have, like, genuine farmers' interests at heart, you know, they're just, you know, like, a front for elements that want to sort of break India."

Although many of the farmers participating in the protests are Sikhs from the Punjab region in the north of India, there is no evidence to support the government’s claims that the protests are overrun by Sikh separatists. (Photo: Harvinder Chandigarh, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BASCOMB: Well, tell us please a bit about the history in India when it comes to jailing protesters and activists, both the, the history and the present, for that matter.

SHARMA: One can argue that, you know, the crackdown against activists and you know, independent voices have sort of intensified over the past few years, particularly, you know, under the current regime. But India doesn't really have a very good reputation, so to speak, about dealing with criticism. People have been arrested in the past. It's not that, you know, like, all of this is something very new to India. But, you know, it certainly can be argued that the intensity has really gone up in the past at least five years.

BASCOMB: And why are climate activists the target here, would you say?

SHARMA: The reason that they've been targeted is because Greta Thunberg tweeted out a toolkit, and it involved a lot of climate activists in India. As to why climate activists have involved themselves, I think Greta Thunberg really put it really well, that democracy and science are interlinked. And you know, if you don't respect democracy, you probably won't respect science.

India has a history of jailing protesters, but crackdowns have intensified under Prime Minister Narendra Modi. (Photo: Emily Abrams, Flickr, CC-BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Of course, the devastating effects of climate change on farming are the backdrop for the current protests in India. What is Prime Minister Modi's approach to addressing climate change in India?

SHARMA: So, yeah, well, Prime Minister Modi has spoken about the need of you know, combating climate change. And India is, of course, a party to the Paris Climate Accord. But there is very little to show for, because there's always this argument that India -- and it's the same argument that, you know, China has also made often -- that like we're a growing economy, we're, we're an emerging economy and we need to rely on fossil fuel. So like the shift to green energy isn't going to happen overnight. And the goals under the Paris Climate Accord are, you know, quite lax compared to what, you know, more developed economies have. As far as climate change is concerned, this government has very little to show for.

BASCOMB: Well, Aditya, I really appreciate you coming on to talk with us about this. I mean, I've reached out to a few other Indian journalists who understandably don't want to get involved with this story and perhaps be on the bad side of a government, which, you know, puts people in jail for speaking out against it.

I still #StandWithFarmers and support their peaceful protest.

— Greta Thunberg (@GretaThunberg) February 4, 2021

No amount of hate, threats or violations of human rights will ever change that. #FarmersProtest

SHARMA: Yeah. So, you know, a lot of journalists have also been arrested. There was a journalist with a magazine, this Caravan journalist, his name is Mandeep Punia. He was arrested and, you know, sent to jail for about two weeks for reporting on these farmer protests, and that got a lot of media attention. But there's also this crackdown on independent journalists and, you know, journalists who don't really get this sort of media attention. So when they're jailed, like, they're not really getting the kind of media attention that would sort of, you know, expedite their release.

BASCOMB: And how safe are you feeling right now, you know, covering these types of stories?

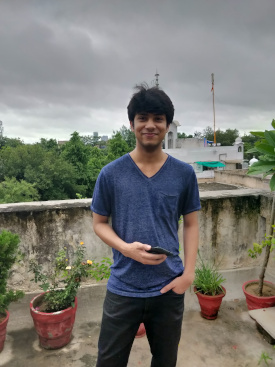

Freelance Journalist Aditya Sharma (Photo: Courtesy of Aditya Sharma)

SHARMA: So I really haven't had, luckily, you know, any problems with the police or, you know, any such problems as such so far, so that way, I kind of do feel a bit privileged. But, of course, there's this constant fear that, you know, something that I write tomorrow or something that I report tomorrow could land me in jail. And, you know, it's sort of something that, you know, you have to constantly work with, but it's the job of a journalist to report and write the facts and, you know, like, cover, you know, the biggest events. And, you know, this is actually an event that directly affects the majority of the country, you know, the vast, vast majority of the country, which is, you know, we're talking about 1.3 billion people here.

BASCOMB: Gosh, well, I wish you luck and I certainly hope that you stay safe in your work there.

SHARMA: Thank you.

BASCOMB: Aditya Sharma is a freelance reporter. Aditya, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

SHARMA: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Aditya Sharma for Deutsche Welle | “India: Police Seek Arrests Over Farmer Protests ‘Toolkit’”

- More Deutsche Welle coverage of Disha Ravi

- An updated version of the toolkit document shared by Greta Thunberg

- Living on Earth’s segment about India’s farm crisis and climate change

- The Guardian | “Disha Ravi: The Climate Activist Who Became The Face Of India’s Crackdown On Dissent”

- More context from Open Democracy Opinion | “Why India’s Farmers’ Protests Have Sikhs Fearing Violent Attacks”

- Follow Aditya Sharma's reporting on Twitter

[MUSIC: Ravi Shankar and Philip Glass, “Prashanti” on Passages, by Ravi Shankar, Private Music]

Beyond the Headlines

A catalytic converter installed on a Volkswagen Vanagon in 2013. (Photo: Vanagon Blog, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, let's take a look beyond the headlines now with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with environmental health news at ehn.org. and dailyclimate.org. Joining us now on the line from Atlanta, Georgia. How you doing, Peter? And what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve, we're gonna start with a very, very unique environmentally themed crime wave.

CURWOOD: Okay, environmental crime wave. Stolen trees, what are we talking about?

DYKSTRA: Well thieves across the country are beginning to swipe catalytic converters that's that pollution control device that's been added to cars for the last 20 years or so. Those gadgets are absolutely full of precious metals, including palladium, and prices for palladium are going through the roof to the point that palladium is now more costly than gold.

CURWOOD: Yeah. And there's also platinum in those catalytic converters. So what's going on? How are people stealing these things?

DYKSTRA: Thieves shimmy under the gasoline powered cars, hacksaw the converters off the vehicles. Replacing the converters can cost $2500 or more.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I'm well aware I had a car that was going to need a new one and it was worth more than the car itself. Of course, both platinum and palladium can help neutralize some pollutants like the nitrous oxides and, and such.

DYKSTRA: That's right, palladium is rare metal. Right now in the market. It's running about $2500 an ounce compared to gold, which is about 1800 an ounce these days. Other uses for palladium include everything from jewelry, dentistry, watchmaking, blood sugar, test strips, aircraft, spark plugs, surgical instruments, electrical contents, and flutes.

CURWOOD: Yeah. Well, I can see that because you know, back in the day, really nice flute was made out of silver, so palladium must have even more attractive qualities. Let's move on now to what's next. And what is that? Peter, what do you have for us next?

DYKSTRA: We're gonna go to Norway, the number one country in the world for electric vehicle sales. Norway is running at 56% of all new vehicles sold are electric. Compare that to the US here in this country where 2% electric vehicle sales.

Morten Harket, Norwegian singer and part of the pop-music group A-ha, has been a vocal proponent of electric vehicles. EVs make up over half of the market share in Norway. (Photo: Sven-Sebastian Sajak, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Well wait Peter, how fair is that? I mean, Norway has got a population what the size of Wisconsin or something? We have 330 million people here in the US.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, but in terms of market share, it's huge there. It took a number of things, some solid policy, need for clean energy, and a mighty famous pop star named Morten Harket. He was the lead singer for the band A-ha. Famous to me because they're alphabetically first in my ancient iPod. And the one hit wonder from Morten Harket and A-ha is of course, [SINGS] "take on me, take on me".

CURWOOD: Okaay. Wait a second Peter, let's not sing here.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, we don't want me to sing. You're absolutely right. But thanks to Harket and other EV advocates, Norway's vehicle import market tipped the scales in favor of electric vehicles by making imports like Volkswagens more expensive through added taxes, EVs cheaper, and therefore, they're dominating vehicle sales in about 56%.

CURWOOD: So a pop star helped flip this market? Hmm.

DYKSTRA: A-ha!

CURWOOD: Oh, okay. I'll take that as a cue to move on Peter. Which means we should consider something from history. What would you like us to consider today?

DYKSTRA: February 25, 2007, Al Gore's slideshow turned into a hit movie, An Inconvenient Truth was released. Course slideshows are the kind of thing you'd fall asleep to in middle school, or at least I would fall asleep to them, but Gore's down to earth, un-science-y delivery, and the fact that An Inconvenient Truth followed climate change linked mega disasters like Hurricane Katrina made it the right slideshow at the right time.

CURWOOD: Yeah, it was wildly popular. I remember standing in line for a good while to get a ticket to go see it.

Al Gore’s popular film “An Inconvenient Truth” raised the alarm across the world about the reality of climate change. (Photo: Andreas Weith, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DYKSTRA: It was wildly popular with award season too. The theme song won a Grammy. Gore won an Oscar for documentaries. And of course, that same here, he shared a Nobel Peace Prize.

CURWOOD: Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and DailyClimate.org. We will talk again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the living on earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- The New York Times | “Thieves Nationwide Are Slithering Under Cars, Swiping Catalytic Converters”

- The Guardian | “Electric Cars Rise to Record 54% Market Share in Norway”

- Grist | “An Oral History of ‘An Inconvenient Truth’”

[MUSIC: Take On Me https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=djV11Xbc914]

BASCOMB: Coming up –Tom Vilsack is set to be confirmed as the new US Secretary of Agriculture.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Energipsy, “Gipsea” on Gypsy Fire, by Francesco Grant, Narada World]

A New Leader for USDA

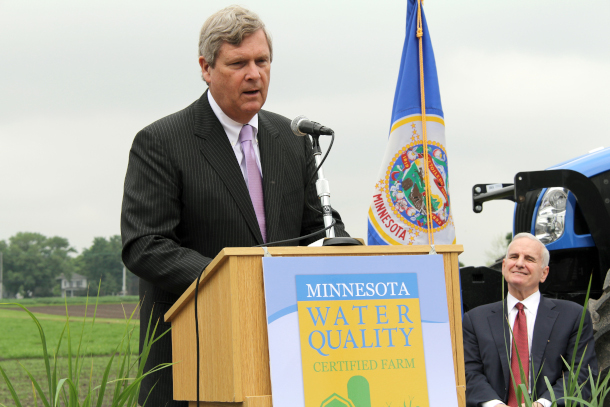

Tom Vilsack speaking about Minnesota Agricultural Water Quality Certification in 2013. (Photo: Julie MacSwain, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

A final Senate vote to confirm Tom Vilsack as Secretary of Agriculture has been scheduled for February 23, and he has broad bipartisan support. The former Democratic governor of Iowa and one-time presidential candidate was also Agriculture Secretary for President Obama. But a lot has changed in the last four years. Catastrophic wildfires spurred by climate change have ravaged parts of the 200 million-acre National Forest system the USDA administers. And the Covid pandemic has tipped twenty percent of American households deeper into food insecurity and led to food shortages. Early on farmers, lacking a market were forced to dump milk and the virus ripped through meat-packing workers. During confirmation hearings before the Senate Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry Committee on February 2nd Tom Vilsack pledged to align the vast National Forest system with the Biden Administration goal of conserving at least 30% of US lands and waters by 2030. He also promised support of climate-smart agricultural practices to create new income and jobs for rural Americans.

VILSACK: I think there's an opportunity for us to create new markets incentives for soil health, for carbon sequestration for methane, capture and reuse of by building a rural economy based on bio manufacturing, protecting our force, turning waste material into new chemicals and materials and fabrics and fibers, creating more jobs in rural America creating greater farm income stability, and also reducing emissions.

CURWOOD: Tom Vilsack also said he would attack systemic racism at the USDA.

VILSACK: We need to fully deeply and completely address the long-standing inequities, unfairness and discrimination that has been the history of USDA programs for far too long, to a future where all are treated equitably, fairly, where there is zero tolerance for discrimination, where programs actually open up opportunity for all who need help and lift the burden of persistent poverty for those most in need.

CURWOOD: The biggest part of the Agriculture Department budget is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program which provides more than 40 million Americans with food aid. Secretary-designate Vilsack promised to reverse the actions of the previous administration, which tried to shrink food assistance benefits and failed to help many people who suddenly lost jobs and income in the pandemic. For some perspective on the Vilsack appointment, we are joined now Ricardo Salvador, the food and environment director for the Union of Concerned Scientists. Welcome to Living on Earth!

SALVADOR: Thank you, Steve. It's great to be with you. And I am glad that you've raised the confirmation hearing because there were some subtle nuances that many of us noticed during that confirmation hearing. Mr. Vilsack, to his credit, he of his own volition actually raised that it was important to think about the people that are not able to afford food, how he was actually going to prioritize making more of them eligible to participate in the Food Safety Network, which is the largest budget item in his department. And that's significant because his immediate predecessor had actually done the opposite. He was acting on a worldview that people that used the Food Safety Network were actually lazy, or were trying to cheat the system. So he was trying to make it as difficult as possible for people to qualify for SNAP what used to be called food stamps. So that's a significant difference in attitude and understanding of the purpose of the program that came from Mr. Vilsack. Likewise, he also didn't fall into line in that he actually said that it was very important to take into account the well-being and the health of laborers within the food system all the way from the fields into meatpacking plants. His immediate predecessor didn't even acknowledge those people exist. And if he ever did talk about laborers to him, those were inputs into the system that you know, whose costs were to be minimized. So what the traditional view in agriculture is, is that the laborers that are essential for the whole system operate just input costs, and you want to make your cost as low as possible. So when a secretary of agriculture speaks in the way that Vilsack did during his confirmation hearing, and he talked about them, needing occupational safety protection, that they needed to have a safe environment in which to work and that we needed to treat them with dignity. While in normal conversation that may just seem like it's expected for a secretary of agriculture to speak that way there is a sea change.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic food insecurity more than tripled in the United States. The image above shows the U.S. National Guard distributing food during the COVID-19 pandemic. (Photo: Cpt. Brendan Mackie, U.S. Army National Guard, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Particularly in meatpacking what say does the Secretary of Agriculture have over labor practices there?

SALVADOR: Yeah, that's a very good point because it would actually be OSHA, Occupational Safety and Health, or CDC, you know, so respectively, the Department of Labor and the Department of Health and Human Services that would have purview over a lot of the factors that determine how safe the environment is for workers in meatpacking plants. But the Secretary of Agriculture actually does have purview over one really important feature of the way that meatpacking plants work. And the Meatpacking industry, you have a disassembly line, you're essentially hacking away the pieces of the carcasses that are moving in front of you. And here's the key thing, the faster those carcasses are flying in front of you, and you hack away at the bit that you're responsible for, then the more profit the industry makes, you know, it's essentially how much can you process per unit of time. And if these were machines, you know, you could make an argument for that represent an efficiency because these are human beings, that's not efficiency that's exploitation. Because just so that you have an idea, depending on the species, we're talking about, say and poultry, you could be expected to hack away at about 181 of these carcasses per minute. And you're manipulating very sharp instruments and you can't stop because if you stop or if you miss it affects the entire disassembly line. So obviously the humane thing to do is to slow down the speed of those disassembly lines so that you actually have a humane occupation for these people to discharge. That is completely under the purview of the Secretary of Agriculture and prior secretaries of agriculture, not only Mr. Vilsack's immediate predecessor, but Mr. Vilsack himself when he was there, the first time actually supported the industry's demand that they sanction higher line speeds. So this is something that he can remedy because he can change things that he previously supported.

CURWOOD: So when Tom Vilsack was Secretary of Agriculture back during the Obama administration, the department was accused of discrimination favoring white farmers versus black and Hispanic and Native American farmers. And, in fact, among the cases that were filed, years ago, one of them called Keepseagle v. Vilsack resulted in millions in compensation for discriminatory claims. So to what extent do you think that Mr. Vilsack is going to change his approach to how farmers of color are handled by the USDA? Both in view of the lawsuits that had to be settled that had his name on it, and to any change in attitudes that you've noticed.

As the Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack would oversee the US Forest Service which has been dealing with catastrophic wildfire seasons due to climate disruption. (Photo: Mike McMiller, USFS, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

SALVADOR: Yeah. Well, if the only honest answer to that question is that that remains to be seen. Obviously, we would be just speculating right now. However, the way that Vilsack the second, you know, this is what I'm calling him now is shown up so far, is very different from the way that he presented the first time around. And one of the key indicaters of that is that when he held listening sessions with members of the African American farming community, he genuinely was listening, which we can tell because of the policies that he's recommending that the Congress move. But among these things, just to give you an idea, what I'm talking about is actually loan forgiveness for African American farmers. And actually a pause on foreclosures on African American farmers who are under great economic stress because many of them lost markets during the pandemic, every listener needs to understand that the history of the USDA has been racist from its inception in 1862. As a matter of fact, you can say with a straight face, its mission has been racist. You think of the year 1862 this is just before the Civil War starts out. The same President Lincoln who signed the department into existence also signed the Homestead Act, which basically distributed Native American land to white settlers. He also signed the Morrill Act, which essentially made a series of agricultural colleges exist in every state that largely served the overwhelmingly white farming population. To this day that population is 96% white, and they control 98% of agricultural land. That is the constituency that The Department of Agriculture has been serving and has been favoring. And the way that they express their racism is to those Farm Service Agency offices where both administrators as well as committees decide who is going to gain access to the federal funds, the programming, the low interest credit that goes out the front doors. And those lawsuits that you mentioned, essentially documented the extent of systematic discrimination against farmers of color and women. So to be fair to Mr. Vilsack, his name is attached to that lawsuit, because there was a lawsuit against the Department of Agriculture and he was the secretary. The one lesson that I think he learned from his first administration is that, while he may have theoretically been acquainted with the racist history of his department, he really left it up to subordinates and the department to try to remedy that as a result of the settlements of both lawsuits. And clearly, really did not deal with the underlying racism. And so now there's an opportunity to undo that. And so a key indicator that he means business is that he has stated publicly, he means to change the constitution of the Farm Service Agency offices, and who is actually made a member so that they're not primarily these white local groups that historically are just going to be benefiting themselves. So that's something we're going to be keeping an eye on in order to see the seriousness with which Vilsack the second is going to be approaching not only his charge, but also the promises that he's been making in public.

CURWOOD: I think it's fair to say that right now, the way the Agriculture Department operates with many farmers, involves the financial subsidy that they get through what's called crop insurance and such. And the bottom line is that if you're big and you have a nice balance sheet, your bank or the bank you deal with will accept that that federal guarantee is good to go and lend you the money. Whereas if you're small, and maybe not as rich, they may not even let you fill out the application or certainly, except that. To what extent then, are American taxpayers subsidizing the large agribusiness corporations that are squeezing out the small farmers?

SALVADOR: They're subsidizing it directly. That's entirely the purpose of farm programs and you've put your finger on something that many folks, even folks that are really familiar with agriculture don't fully understand. Let me give you an example of that many folks analyze those subsidies by saying that essentially what they're doing is helping to create an affordable food supply. So the food supply in the United States, first of all, is not affordable, it is one of the most expensive food systems that there is on the planet. But what people actually mean when they claim that the food system is affordable, is that if you're rich, you can buy what the US food system produces. So that's point number one, the subsidies to agriculture really not doing anything to make that food more affordable. Instead, you have to follow where those subsidies are going. Farmers do receive them and what farmers do with that is to buy their tractors by their seed by their fertilizer. And so if you follow the dollar, where it's ending up is the people that sell the fertilizer, the people that sell the seed. So the reason why this is significant in terms of farm subsidies, let's say that you're an industry that's producing expensive hybrid seed or you're an industry that's producing expensive equipment for farmers. You know, some of this equipment can cost 100 - $150,000 a shot. Then you're not going to be making the investments in those industries unless you're sure that those farmers are going to be there year in and year out to be buying those products from you. But because those farmers are vulnerable to a hailstorm or a cyclone essentially wiping out their business in 10 seconds, then that is not a safe bet to make that those farmers are going to be there. So now bringing in those those subsidies, we make farmers whole when the market goes south, we make farmers whole when a windstorm or hurricane, you know, hailstorm happens. So the ultimate beneficiaries, then it's the industries that sell to and that buy from farmers. So when you look at the lobbying that happens for agricultural programs, guess who's front and center and making the strongest arguments for that? It's those businesses is the businesses that sell to and that buy from farmers. That's what the agricultural subsidies are for. So the answer to your question is, we're directly subsidizing the major agribusinesses that otherwise are making arguments about how he loved the free market, but are the most socialized segment of the American economy. Those federal subsidies are actually built into their business models.

Ricardo Salvador is the Food and Environment Director at the Union of Concerned Scientists, and a former associate professor of agronomy at Iowa State University. While at ISU, Dr. Salvador taught what is regarded as the first course in sustainable agriculture at a land-grant university, and his graduate students conducted some of the original academic research on community-supported agriculture. (Photo: Courtesy of Ricardo Salvador)

CURWOOD: Let's talk a bit about carbon, the Biden Harris administration has said, we're going to deal with the question of climate change with an all of government approach. And there's much talk about the ability of farmland to help sequester carbon. For example, there's the in the USDA, there's a Commodity Credit Corporation. And there's some talk about having that become a carbon bank to pay farmers for practices that could limit greenhouse gases or even help extract them out of the air. How might this proved to be an effective incentive for farmers, when it comes towards moving the US towards dealing with a climate emergency? And how much do we know to accurately monetize such things at this point?

SALVADOR: So I'll give you the short answers. It's all to the good that we're moving to provide an economic incentive for farmers to contribute to mitigating climate change. And how much we know is not enough and as a matter of fact, is very limited in terms of monetizing those rewards. So there's a lot that we don't know, but which is knowable, and we just haven't invested in learning more about and that's the knowledge that the USDA has in its mission to generate. They just haven't chosen to do that to a large extent in the past. And now we have a real urgency to do that because the last thing that we want to do is to fritter away the moment when we have a president that recognizes climate change is real, human actions contribute to climate change, and we need programs in order to deal with this. And so when we go to say, okay, how do we incentivize and reward farmers to do that we don't want to do this in a way that commoditizes carbon so that then it becomes this sort of large volume, low value kind of proposition that is ultimately economically extractive and others other people benefit. And the farmers are the ones who benefit the least from that and to build a false economy where we think we're sequestering carbon, but we have no way of measuring it or and verifying how much actual carbon is being sequestered by agricultural practices. So yes, by all means, we need to get going on this and urgently it is it is really one of the most important Agricultural Science priorities that there is right now. But not delude ourselves about what we know so far, and what we need to invest in in order to learn more about

CURWOOD: Ricardo Salvador is the Food and Environment Program Director of the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SALVADOR: It was a pleasure. Thank you for having me, Steve.

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “USDA Secretary of Agriculture Nominee Tom Vilsack Clears First Hurdle, Says He Will Focus on Climate Change”

- AgWeb | “Senate to Vote on Tom Vilsack’s Secretary of Agriculture Confirmation Next Week”

- Union of Concerned Scientists | “If Confirmed Again, Former USDA Secretary Vilsack Must Enact Ambitious Science-Based Policies for Farms and Food”

- NY Times | “Goodbye, U.S.D.A., Hello, Department of Food and Well-Being”

- Politico | “Black Farmers, Civil Rights Advocates Seething Over Vilsack Pick”

- The Washington Post | “At Chicken Plants, Chemicals Blamed For Health Ailments Are Poised To Proliferate”

- Watch Tom Vilsack’s Senate Confirmation Hearing

[MUSIC: Chick Corea & Bela Fleck, “Brazil” on The Enchantment, by Ary Barroso, Concord Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – From religious symbols to manicures we’ll take a deep dive into the many surprising ways insects feature in our daily lives. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Chick Corea & Bela Fleck, “Spectacle” The Enchantment, by Bela Fleck, Concord Records]

The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World

There are around 10 quintillion insects on the planet, says Edward D. Melillo, author of The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World. (Photo: Phil Fiddyment, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

There are some 800,000 known species of insects, and surely many more not yet discovered. Many of us may not realize it but insects actually play a critical role in our daily lives. Insects pollinate our crops, of course, they’re also used to make our apples shiny, our wood water proof, and some candy just the right shade of red. In his book, Butterfly Effect, Insects and the Making of the Modern World, Edward Melillo takes a deep dive into the surprising history of human-insect relationships and how they have evolved and endured over time. Ted, welcome to Living on Earth!

MELILLO: Thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: Well, the first chapter of your book is full of interesting, bizarre kind of disturbing, fun facts about insects. Can you give us a couple of your favorites?

MELILLO: Sure. So one of my favorites is that there are 10 quintillion insects living on the planet. And it's 10 followed by 18 zeros. But it just goes to show that we're radically outnumbered by insects. And really, in a lot of ways, this is an insect planet that we're just happening to live upon at this moment. And insects are governing all the basic processes that make life possible from plant sex to decay and all sorts of other crucial ecosystem services that didn't insects are responsible for.

BASCOMB: You talked about a study that found some 10,000 species, not individual, but species found in the average North Carolina home. That was shocking [LAUGHS] I don't think it's just North Carolina.

MELILLO: Yeah, it was a study led by an entomologist named Michelle Trautwein from San Francisco. And she and her team of investigators went into houses in North Carolina and they also did another study where they looked at everything from parisian apartments to high mountain huts in Peru, and insects were just everywhere, all the time. And perhaps we don't notice them because they're doing a lot of their work between blades of grass, and under garbage cans and refrigerators but they're, they're doing really important work behind the scenes. And as I show in the book also, they're on our bodies, they're in our food. They're in our pharmaceuticals, and they're really in a lot of ways hosts of what a future planet might look like too.

BASCOMB: You know, I was surprised to read about the role that some insects have played in certain religions. Can you give us a sense of that?

Silkworms are moth caterpillars. Their cocoons are made of a single strand of raw silk that is harvested and woven into smooth, shimmering silk fabric first invented in China thousands of years ago. (Photo: Baishiya_白石崖, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

MELILLO: Oh, yeah, I mean, insects symbolically have played important roles dating way back to scarab beetles and the ancient Egyptians. I talk about dragon flies on Samurai helmets as symbols of bravery and protection. And I talked about in the Christian faith, the idea that many saints carried a profusion of hair shirts on their bodies, and beneath them, lice and fleas were feasting, and they were happy to host these colonies of God's beings on their person. So yeah, insects are sort of with us around us and on us at all times.

BASCOMB: Well, most chapters of your book, take a deep dive on a certain insect. So let's talk about one the domestication of silkworms.

MELILLO: Yeah, it's totally fascinating. I talk in the book about the Chinese princess who 1000s of years ago, was sitting under a mulberry tree, sipping on a cup of tea, and apparently, a silkworm cocoon fell into her teacup she reached in and then she pulled it out, this long, 10 style thread came forth and stretched on and on and on, and it was remarkably strong. And she's considered among the Chinese to be the legendary founder of silk production. But today, we still depend upon billions and billions of tiny caterpillars. We call them silkworms, but they're really caterpillars for the production of our silk. And silk is extremely widely consumed. I mean, who hasn't felt or touched silk at some point. And it's a really, really fascinating story. But it also is a story about a resurgence of a product that seemed to have disappeared in the 1940s after the Second World War, as rayon and polyester seem to be taking over the world. But it turns out that silk has a lot of properties that are inimitable, and engineers have never figured out how to make fibers that have the same kind of strength and flexibility and properties that can reflect light in the ways that silk can. And so once again, many of the human substitutes for these insect secretions turned out to not hold all the promise that we were told they would.

BASCOMB: You talk about shellac in the second chapter of your book. Many listeners may be familiar with shellac. It's a wood varnish and may be used as a nail polish, but they probably don't realize that it actually comes from an insect. Can you tell us more about the bugs that produced shellac and how it's actually made?

MELILLO: Sure, sure. So shellac is the secretion of the female kerria lacca insect. And she lives on fig and acacia trees in India and parts of Southeast Asia, Thailand, southern China. This was the most surprising chapter for me because I knew so little about it. And then I came to learn that 78 RPM records which were basically the medium of the global transmission of sound up until the vinyl era and the 1940s are made out of an insect secretion and that really blew my mind. Female insects have the kerria lacca species secrete it to protect their young from ultraviolet radiation and predators, but then it's harvested by men and women in these regions of the world still today. Millions are employed this way. It's melted down and then turned into a hard substance and broken up into fragments. And it gets re melted in other countries. And so that was mind boggling to go into the extraordinary array of steps that she'll act takes to get, as you said, onto our back deck or fingernails. It's in a hair spray, you go to a grocery store and you buy a shiny apple. And that apple is kept shiny often by shellac, shellac is a an FDA approved coating for many foods. And it's also interior coating for many pills to keep medicines from dissolving too quickly in the highly acidic environment of the stomach. And so we're eating shellac, we're spraying it on our hair. We're putting it on our fingernails, but yet, hardly ever do we remark on the fact that it's an insect secretion that comes from a whole interesting array of locations a world away.

The cochineal is an insect that, when crushed and processed, creates carminic acid that is used to made carmine dye. Today this dye is used primarily to color food and lipstick. (Photo: Vahe Martirosyan, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: See right in your book that shellac is not the only insect produced substance that we're eating regularly. Another whole chapter you write about the coach cochineal, which people crush up to make a red dye in food coloring. Can you tell us more about them?

MELILLO: Sure. So like silk and shellac. The other two oddities I focus on in the book cochineal has an ancient history that goes way back to Peru's paracas culture. The Aztecs and Mayans produced cochineal. And we've got records of Montezuma, the second taking cochineal bags as tribute from his subjects. And the way it's made is again, it's the females who are doing all the work there's a theme here, the female insect bodies are crushed to produce this carmine red dye, and the insects are raised on nopal cacti they dine on the sweet juices inside of the cactus, and then the female raises her young surrounded by kind of a downy secretion, but then it takes about 70,000 female insect bodies to produce a one pound brick of dried cochineal dye. And when Europeans came across this 1500s, after the Spanish conquest of the Americas, they just couldn't get enough of it because it has tremendous fixative properties, it doesn't bleed away and it creates a whole host of brilliant colors. You can combine cochineal with mordants that are basically different types of metals to produce deep sort of Corinthian purple hues. And you can produce these really bright Scarlet reds. And of course for ecclesiastical vestments, and royal robes, Europeans wanted red the color for virility and Christ's blood. And so once they got their hands on this new source of red dye, it became the second most lucrative traded product in the Spanish Empire after only silver. And today, it's made a resurgence and is used as a safe food coloring for all sorts of things, from candy to fake crab legs to specialty cocktails, it's in everything sausages, you name it, it has cochineal. I mean, part of the reason for this is that many of the substitutes for these natural products that people came up with after the Second World War turned out to be toxic. So cochineal has made a comeback just like Sherlock and silk, in part because of the failures of substitution. And I talked about that quite extensively in the book.

BASCOMB: You know, for many Westerners, the idea of purposefully eating bugs can be you know, kind of off putting, but you're right that many people most people are actually already eating insects, and not just in cochineal and shellac, as we've talked about, but in a lot of other ways. Can you give us some examples?

MELILLO: Sure. So right now on the planet about 2 billion people on a regular basis, eat insects, it's just a part of their regular daily diet, almost every world culture some insect dish that's central to their food culture in Japan eating sasa-mochi, which are riverbed harvested larva is very common, bundongi in South Korea are silkworm pupa. I've eaten those and they taste a little like a cross between a peanut and a shrimp. I'd say it was strange but interesting new taste experience. In Mexico chapulines, fried crickets and grasshoppers, a wonderful snack actually really enjoy those. But we're all eating insects, you may not know it, but I'm drinking a cup of coffee, for example. And the United States allows about 10% of the green beans that are brought into this country, the insect body parts. And if drinking coffee or tea, you're most certainly consuming insects. It's in peanut butter and chocolate. The FDA allows insect body parts, there are quotas for both of those as well. So if you can do many of these products on a daily basis, you may not know it but you're consuming insects regularly.

BASCOMB: You know, you've always heard these stories of some bug crawling in your mouth while you're sleeping. But I guess it's a lot more subversive than that.

MELILLO: You know, it's it's totally a cultural thing, because, you know, just imagine, I teach many Chinese students and they think it's so strange that North Americans eat cereal with milk. That is just the most odd combination to them, yet it seems perfectly natural to us. So it's worth reminding ourselves that there's no biological basis for a distaste for insects. It's very culturally conditioned. And we're seeing a lot of indications that maybe this is changing in the United States, for example, at Safeco Field, the field where the Seattle Mariners play. They've got a restaurant there that's been serving up chapulines fried grasshoppers for years, and they're a best seller alongside popcorn, peanuts, and hot dogs. So, you know, this may be the harbinger of things to come. Who knows?

Many people in the world eat insects without realizing it. Coffee, cereals, produce, and other food products contain parts of insects unfortunate enough to be harvested along with the intended crop. (Photo: Popo le Chien, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah, that's the thing. I mean, people talk about insects as being the protein source of the future. And I think it is cultural. I have a friend. She was in the Peace Corps back in the day and she was going to go back to her village in Niger. And she was really excited because she was going back during locusts season, which is a time when they capture the locusts, fire them up, throw some salt on them and you know, eat them like popcorn and she was really stoked to be going back at that time of year.It's something people enjoy.

MELILLO: Absolutely. And in many cultures, I mean much of Southern Africa eating mopane Caterpillar is called mopanes, is very common, and it's a multi million dollar industry that gives protein to people where refrigeration is scarce, it can be a really important alternative. And I'll just give you one statistic for your listeners to think about. In the United States to produce one pound of beef, it takes 1000 gallons of water and two acres of grazing land. To produce one pound of crickets. It takes one gallon of water and two cubic feet of space. And with the crickets, you get about three times the amount of protein, much more iron and nutrients. And essentially, these are freeze dried pulverized and turned into a high protein meal. I certainly think it's going to be part of the array of possible solutions for the future.

BASCOMB: Now, of course, perhaps the most well known and important insect for human beings is the bee. Honey bees give us honey and they pollinate on the order of one in every three bites of food. They're so important. Can you tell us a bit about the history of that relationship? And what's going wrong with it today?

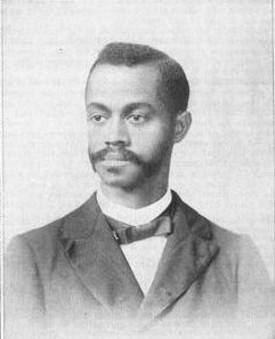

MELILLO: Yeah, so our understanding of pollination is a quite remarkable story in and of itself. And I delve into that quite a bit. One of the most fascinating characters that I came across when I was learning about how we came to know more about pollination was Charles Henry Turner. He was an African American biologist born at the end of the 19th century. And he was the first African American to get a PhD in zoology at the University of Chicago and the first African American to get published in the prestigious journal Science. Yet we know very little about him, he was unable to get a university job because he was black. And so he ended up teaching high school, he had no laboratory no graduate students. And he did all of the pioneering work that led us to really understand how these are actually rational actors that make decisions and move about in this world not as sort of robotic beings but as free thinking individuals as part of social groups. And Turner's story I found truly amazing. Today, the real threats to bees, we talked about them as colony collapse disorder seem to be coming from a variety of sources. One of them though, and it's a big one, are a class of pesticides, known as neonicotinoids, or neonics. They're pesticides that mimic nicotine, which you may know of as as one of the chemical secretions of the tobacco plant. But these chemicals that mimic nicotine are really wreaking havoc on bee colonies, habitat destruction, climate change are big parts of it as well. But also there's a parasitic mite called the Varroa destructor. It's got a very vivid name that has been hurting bee colonies as well. But neonicotinoid this class of chemicals really needs to be banned. Because we depend so much on bees for our fundamental existence on this planet. And it's easy to forget how much we depend upon bees, the almond butter that you might put on a piece of toast in the morning that was all dependent upon bees as is your morning coffee, your tea, many of the vegetables you consume on a regular basis, avocados, broccoli, you name it.

BASCOMB: Well, Ted, what do you suggest for someone that maybe wants to learn more about insects on a personal level? You know, many of us are trapped at home right now with a virus and a captive audience for taking up a new hobby. I don't know what do you think of an ant farmer, any other ideas that you might have?

Charles Henry Turner was a pioneering zoologist who studied the behavior of bees. (Photo: Unknown Photographer, Project Gutenberg, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

MELILLO: Yeah, so I've been raising silkworms, with my seven year old and we've had a remarkable time doing that. We purchased online for about $10 a bunch of little eggs, they showed up in a petri dish there were about 250 of them, they like little poppy seeds. And we put them in a styrofoam chicken incubator which cost us another $10 or so to keep them nice and cozy. And they hatched and we've been watching them grow you have to feed them a lot because they eat about 10 times a day. And it's remarkable to see them growing in front of your very eyes, but it also suggests Just really helping kids become attentive to insects in their lives in other ways, maybe then lice or ticks. You can listen to a crickets chirps for example. And if you do that for 14 seconds, and that add 40 to that number, you'll get a remarkably accurate reading of the temperature in degrees Fahrenheit outdoors. And that's because crickets are exothermic and they respond to the ambient temperature. And they slow down when it's cold and go faster when it's warm. And we tried it with our porch thermometer and every time we got within one or two degrees of an accurate temperature reading by simply listening to the crickets outdoors, so I hope the book in some ways and my work in general creates more attentiveness to what insects are trying to tell us both literally and figuratively about the health of our planet.

BASCOMB: Ted Melillo is a professor of history and Environmental Studies at Amherst College and author of the new book, The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World. Ted, thank you so much for all of these bug stories.

MELILLO: Thanks for talking with me. I really enjoyed it.

[CRICKET SFX http://www.naturesongs.com/cricket1.wav]

CURWOOD: We take you now to the company of crickets.

As Ted Melillo mentioned, crickets are cold blooded and take on the temperature of their environment. They are more active in warmer weather and tend to chirp faster. So, if we count the number of chirps in 14 seconds and then add 40 an 80 degree hot summer night would sound very busy.

[FAST CHIRPING http://www.naturesongs.com/cricket1.wav]

CURWOOD: The chirping sound is actually the male cricket scraping one wing over the other to attract a mate. But on a cool evening, say 50 degrees, his chirping is considerably slower.

[SLOW CHIRPING https://orangefreesounds.com/cricket-chirping-summer-night/]

CURWOOD: These cricket sounds come to us courtesy of Alexander at Orange Free Sounds and Doug Van Gausig.

Related links:

- Click here for more on The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World

- National Geographic | “Five Vital Roles Insects Play in Our Ecosystem”

- The Old Farmers’ Almanac | “Predict the Temperature with Cricket Chirps!”

[MUSIC: Bill Tyers, “When You Wish Upon a Star” unreleased, by Leigh Harline and Ned Washington, Guitar Downunder]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Grace Callahan, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Paige Greenfield, Leah Jablo, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Natalie Seo, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth