The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World

Air Date: Week of February 19, 2021

There are around 10 quintillion insects on the planet, says Edward D. Melillo, author of The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World. (Photo: Phil Fiddyment, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

Insects far outnumber us on this planet, and they’ve shaped the course of human history. Edward D. Melillo, the author of The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to share stories about the ancient relationship between human society and insects, and the critical need to preserve insect biodiversity for future generations.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

There are some 800,000 known species of insects, and surely many more not yet discovered. Many of us may not realize it but insects actually play a critical role in our daily lives. Insects pollinate our crops, of course, they’re also used to make our apples shiny, our wood water proof, and some candy just the right shade of red. In his book, Butterfly Effect, Insects and the Making of the Modern World, Edward Melillo takes a deep dive into the surprising history of human-insect relationships and how they have evolved and endured over time. Ted, welcome to Living on Earth!

MELILLO: Thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: Well, the first chapter of your book is full of interesting, bizarre kind of disturbing, fun facts about insects. Can you give us a couple of your favorites?

MELILLO: Sure. So one of my favorites is that there are 10 quintillion insects living on the planet. And it's 10 followed by 18 zeros. But it just goes to show that we're radically outnumbered by insects. And really, in a lot of ways, this is an insect planet that we're just happening to live upon at this moment. And insects are governing all the basic processes that make life possible from plant sex to decay and all sorts of other crucial ecosystem services that didn't insects are responsible for.

BASCOMB: You talked about a study that found some 10,000 species, not individual, but species found in the average North Carolina home. That was shocking [LAUGHS] I don't think it's just North Carolina.

MELILLO: Yeah, it was a study led by an entomologist named Michelle Trautwein from San Francisco. And she and her team of investigators went into houses in North Carolina and they also did another study where they looked at everything from parisian apartments to high mountain huts in Peru, and insects were just everywhere, all the time. And perhaps we don't notice them because they're doing a lot of their work between blades of grass, and under garbage cans and refrigerators but they're, they're doing really important work behind the scenes. And as I show in the book also, they're on our bodies, they're in our food. They're in our pharmaceuticals, and they're really in a lot of ways hosts of what a future planet might look like too.

BASCOMB: You know, I was surprised to read about the role that some insects have played in certain religions. Can you give us a sense of that?

Silkworms are moth caterpillars. Their cocoons are made of a single strand of raw silk that is harvested and woven into smooth, shimmering silk fabric first invented in China thousands of years ago. (Photo: Baishiya_白石崖, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

MELILLO: Oh, yeah, I mean, insects symbolically have played important roles dating way back to scarab beetles and the ancient Egyptians. I talk about dragon flies on Samurai helmets as symbols of bravery and protection. And I talked about in the Christian faith, the idea that many saints carried a profusion of hair shirts on their bodies, and beneath them, lice and fleas were feasting, and they were happy to host these colonies of God's beings on their person. So yeah, insects are sort of with us around us and on us at all times.

BASCOMB: Well, most chapters of your book, take a deep dive on a certain insect. So let's talk about one the domestication of silkworms.

MELILLO: Yeah, it's totally fascinating. I talk in the book about the Chinese princess who 1000s of years ago, was sitting under a mulberry tree, sipping on a cup of tea, and apparently, a silkworm cocoon fell into her teacup she reached in and then she pulled it out, this long, 10 style thread came forth and stretched on and on and on, and it was remarkably strong. And she's considered among the Chinese to be the legendary founder of silk production. But today, we still depend upon billions and billions of tiny caterpillars. We call them silkworms, but they're really caterpillars for the production of our silk. And silk is extremely widely consumed. I mean, who hasn't felt or touched silk at some point. And it's a really, really fascinating story. But it also is a story about a resurgence of a product that seemed to have disappeared in the 1940s after the Second World War, as rayon and polyester seem to be taking over the world. But it turns out that silk has a lot of properties that are inimitable, and engineers have never figured out how to make fibers that have the same kind of strength and flexibility and properties that can reflect light in the ways that silk can. And so once again, many of the human substitutes for these insect secretions turned out to not hold all the promise that we were told they would.

BASCOMB: You talk about shellac in the second chapter of your book. Many listeners may be familiar with shellac. It's a wood varnish and may be used as a nail polish, but they probably don't realize that it actually comes from an insect. Can you tell us more about the bugs that produced shellac and how it's actually made?

MELILLO: Sure, sure. So shellac is the secretion of the female kerria lacca insect. And she lives on fig and acacia trees in India and parts of Southeast Asia, Thailand, southern China. This was the most surprising chapter for me because I knew so little about it. And then I came to learn that 78 RPM records which were basically the medium of the global transmission of sound up until the vinyl era and the 1940s are made out of an insect secretion and that really blew my mind. Female insects have the kerria lacca species secrete it to protect their young from ultraviolet radiation and predators, but then it's harvested by men and women in these regions of the world still today. Millions are employed this way. It's melted down and then turned into a hard substance and broken up into fragments. And it gets re melted in other countries. And so that was mind boggling to go into the extraordinary array of steps that she'll act takes to get, as you said, onto our back deck or fingernails. It's in a hair spray, you go to a grocery store and you buy a shiny apple. And that apple is kept shiny often by shellac, shellac is a an FDA approved coating for many foods. And it's also interior coating for many pills to keep medicines from dissolving too quickly in the highly acidic environment of the stomach. And so we're eating shellac, we're spraying it on our hair. We're putting it on our fingernails, but yet, hardly ever do we remark on the fact that it's an insect secretion that comes from a whole interesting array of locations a world away.

The cochineal is an insect that, when crushed and processed, creates carminic acid that is used to made carmine dye. Today this dye is used primarily to color food and lipstick. (Photo: Vahe Martirosyan, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: See right in your book that shellac is not the only insect produced substance that we're eating regularly. Another whole chapter you write about the coach cochineal, which people crush up to make a red dye in food coloring. Can you tell us more about them?

MELILLO: Sure. So like silk and shellac. The other two oddities I focus on in the book cochineal has an ancient history that goes way back to Peru's paracas culture. The Aztecs and Mayans produced cochineal. And we've got records of Montezuma, the second taking cochineal bags as tribute from his subjects. And the way it's made is again, it's the females who are doing all the work there's a theme here, the female insect bodies are crushed to produce this carmine red dye, and the insects are raised on nopal cacti they dine on the sweet juices inside of the cactus, and then the female raises her young surrounded by kind of a downy secretion, but then it takes about 70,000 female insect bodies to produce a one pound brick of dried cochineal dye. And when Europeans came across this 1500s, after the Spanish conquest of the Americas, they just couldn't get enough of it because it has tremendous fixative properties, it doesn't bleed away and it creates a whole host of brilliant colors. You can combine cochineal with mordants that are basically different types of metals to produce deep sort of Corinthian purple hues. And you can produce these really bright Scarlet reds. And of course for ecclesiastical vestments, and royal robes, Europeans wanted red the color for virility and Christ's blood. And so once they got their hands on this new source of red dye, it became the second most lucrative traded product in the Spanish Empire after only silver. And today, it's made a resurgence and is used as a safe food coloring for all sorts of things, from candy to fake crab legs to specialty cocktails, it's in everything sausages, you name it, it has cochineal. I mean, part of the reason for this is that many of the substitutes for these natural products that people came up with after the Second World War turned out to be toxic. So cochineal has made a comeback just like Sherlock and silk, in part because of the failures of substitution. And I talked about that quite extensively in the book.

BASCOMB: You know, for many Westerners, the idea of purposefully eating bugs can be you know, kind of off putting, but you're right that many people most people are actually already eating insects, and not just in cochineal and shellac, as we've talked about, but in a lot of other ways. Can you give us some examples?

MELILLO: Sure. So right now on the planet about 2 billion people on a regular basis, eat insects, it's just a part of their regular daily diet, almost every world culture some insect dish that's central to their food culture in Japan eating sasa-mochi, which are riverbed harvested larva is very common, bundongi in South Korea are silkworm pupa. I've eaten those and they taste a little like a cross between a peanut and a shrimp. I'd say it was strange but interesting new taste experience. In Mexico chapulines, fried crickets and grasshoppers, a wonderful snack actually really enjoy those. But we're all eating insects, you may not know it, but I'm drinking a cup of coffee, for example. And the United States allows about 10% of the green beans that are brought into this country, the insect body parts. And if drinking coffee or tea, you're most certainly consuming insects. It's in peanut butter and chocolate. The FDA allows insect body parts, there are quotas for both of those as well. So if you can do many of these products on a daily basis, you may not know it but you're consuming insects regularly.

BASCOMB: You know, you've always heard these stories of some bug crawling in your mouth while you're sleeping. But I guess it's a lot more subversive than that.

MELILLO: You know, it's it's totally a cultural thing, because, you know, just imagine, I teach many Chinese students and they think it's so strange that North Americans eat cereal with milk. That is just the most odd combination to them, yet it seems perfectly natural to us. So it's worth reminding ourselves that there's no biological basis for a distaste for insects. It's very culturally conditioned. And we're seeing a lot of indications that maybe this is changing in the United States, for example, at Safeco Field, the field where the Seattle Mariners play. They've got a restaurant there that's been serving up chapulines fried grasshoppers for years, and they're a best seller alongside popcorn, peanuts, and hot dogs. So, you know, this may be the harbinger of things to come. Who knows?

Many people in the world eat insects without realizing it. Coffee, cereals, produce, and other food products contain parts of insects unfortunate enough to be harvested along with the intended crop. (Photo: Popo le Chien, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah, that's the thing. I mean, people talk about insects as being the protein source of the future. And I think it is cultural. I have a friend. She was in the Peace Corps back in the day and she was going to go back to her village in Niger. And she was really excited because she was going back during locusts season, which is a time when they capture the locusts, fire them up, throw some salt on them and you know, eat them like popcorn and she was really stoked to be going back at that time of year.It's something people enjoy.

MELILLO: Absolutely. And in many cultures, I mean much of Southern Africa eating mopane Caterpillar is called mopanes, is very common, and it's a multi million dollar industry that gives protein to people where refrigeration is scarce, it can be a really important alternative. And I'll just give you one statistic for your listeners to think about. In the United States to produce one pound of beef, it takes 1000 gallons of water and two acres of grazing land. To produce one pound of crickets. It takes one gallon of water and two cubic feet of space. And with the crickets, you get about three times the amount of protein, much more iron and nutrients. And essentially, these are freeze dried pulverized and turned into a high protein meal. I certainly think it's going to be part of the array of possible solutions for the future.

BASCOMB: Now, of course, perhaps the most well known and important insect for human beings is the bee. Honey bees give us honey and they pollinate on the order of one in every three bites of food. They're so important. Can you tell us a bit about the history of that relationship? And what's going wrong with it today?

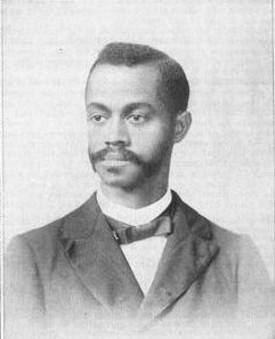

MELILLO: Yeah, so our understanding of pollination is a quite remarkable story in and of itself. And I delve into that quite a bit. One of the most fascinating characters that I came across when I was learning about how we came to know more about pollination was Charles Henry Turner. He was an African American biologist born at the end of the 19th century. And he was the first African American to get a PhD in zoology at the University of Chicago and the first African American to get published in the prestigious journal Science. Yet we know very little about him, he was unable to get a university job because he was black. And so he ended up teaching high school, he had no laboratory no graduate students. And he did all of the pioneering work that led us to really understand how these are actually rational actors that make decisions and move about in this world not as sort of robotic beings but as free thinking individuals as part of social groups. And Turner's story I found truly amazing. Today, the real threats to bees, we talked about them as colony collapse disorder seem to be coming from a variety of sources. One of them though, and it's a big one, are a class of pesticides, known as neonicotinoids, or neonics. They're pesticides that mimic nicotine, which you may know of as as one of the chemical secretions of the tobacco plant. But these chemicals that mimic nicotine are really wreaking havoc on bee colonies, habitat destruction, climate change are big parts of it as well. But also there's a parasitic mite called the Varroa destructor. It's got a very vivid name that has been hurting bee colonies as well. But neonicotinoid this class of chemicals really needs to be banned. Because we depend so much on bees for our fundamental existence on this planet. And it's easy to forget how much we depend upon bees, the almond butter that you might put on a piece of toast in the morning that was all dependent upon bees as is your morning coffee, your tea, many of the vegetables you consume on a regular basis, avocados, broccoli, you name it.

BASCOMB: Well, Ted, what do you suggest for someone that maybe wants to learn more about insects on a personal level? You know, many of us are trapped at home right now with a virus and a captive audience for taking up a new hobby. I don't know what do you think of an ant farmer, any other ideas that you might have?

Charles Henry Turner was a pioneering zoologist who studied the behavior of bees. (Photo: Unknown Photographer, Project Gutenberg, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

MELILLO: Yeah, so I've been raising silkworms, with my seven year old and we've had a remarkable time doing that. We purchased online for about $10 a bunch of little eggs, they showed up in a petri dish there were about 250 of them, they like little poppy seeds. And we put them in a styrofoam chicken incubator which cost us another $10 or so to keep them nice and cozy. And they hatched and we've been watching them grow you have to feed them a lot because they eat about 10 times a day. And it's remarkable to see them growing in front of your very eyes, but it also suggests Just really helping kids become attentive to insects in their lives in other ways, maybe then lice or ticks. You can listen to a crickets chirps for example. And if you do that for 14 seconds, and that add 40 to that number, you'll get a remarkably accurate reading of the temperature in degrees Fahrenheit outdoors. And that's because crickets are exothermic and they respond to the ambient temperature. And they slow down when it's cold and go faster when it's warm. And we tried it with our porch thermometer and every time we got within one or two degrees of an accurate temperature reading by simply listening to the crickets outdoors, so I hope the book in some ways and my work in general creates more attentiveness to what insects are trying to tell us both literally and figuratively about the health of our planet.

BASCOMB: Ted Melillo is a professor of history and Environmental Studies at Amherst College and author of the new book, The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World. Ted, thank you so much for all of these bug stories.

MELILLO: Thanks for talking with me. I really enjoyed it.

[CRICKET SFX http://www.naturesongs.com/cricket1.wav]

CURWOOD: We take you now to the company of crickets.

As Ted Melillo mentioned, crickets are cold blooded and take on the temperature of their environment. They are more active in warmer weather and tend to chirp faster. So, if we count the number of chirps in 14 seconds and then add 40 an 80 degree hot summer night would sound very busy.

[FAST CHIRPING http://www.naturesongs.com/cricket1.wav]

CURWOOD: The chirping sound is actually the male cricket scraping one wing over the other to attract a mate. But on a cool evening, say 50 degrees, his chirping is considerably slower.

[SLOW CHIRPING https://orangefreesounds.com/cricket-chirping-summer-night/]

CURWOOD: These cricket sounds come to us courtesy of Alexander at Orange Free Sounds and Doug Van Gausig.

Links

Click here for more on The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World

National Geographic | “Five Vital Roles Insects Play in Our Ecosystem”

The Old Farmers’ Almanac | “Predict the Temperature with Cricket Chirps!”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth